Improved Photoelectrochemical Performance of MoS2 through Morphology-Controlled Chemical Vapor Deposition Growth on Graphene

Abstract

:1. Introduction

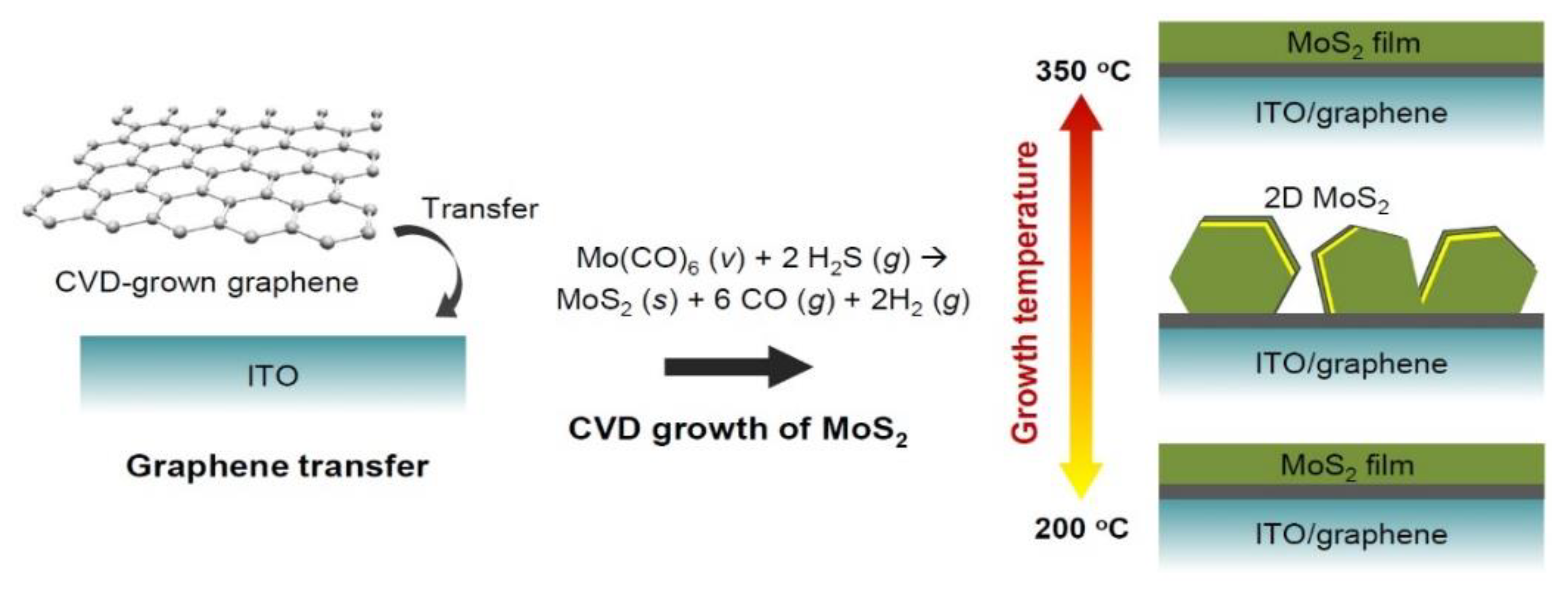

2. Experimental

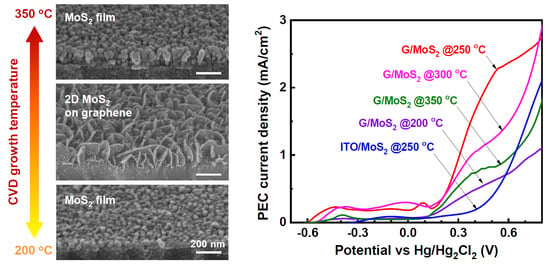

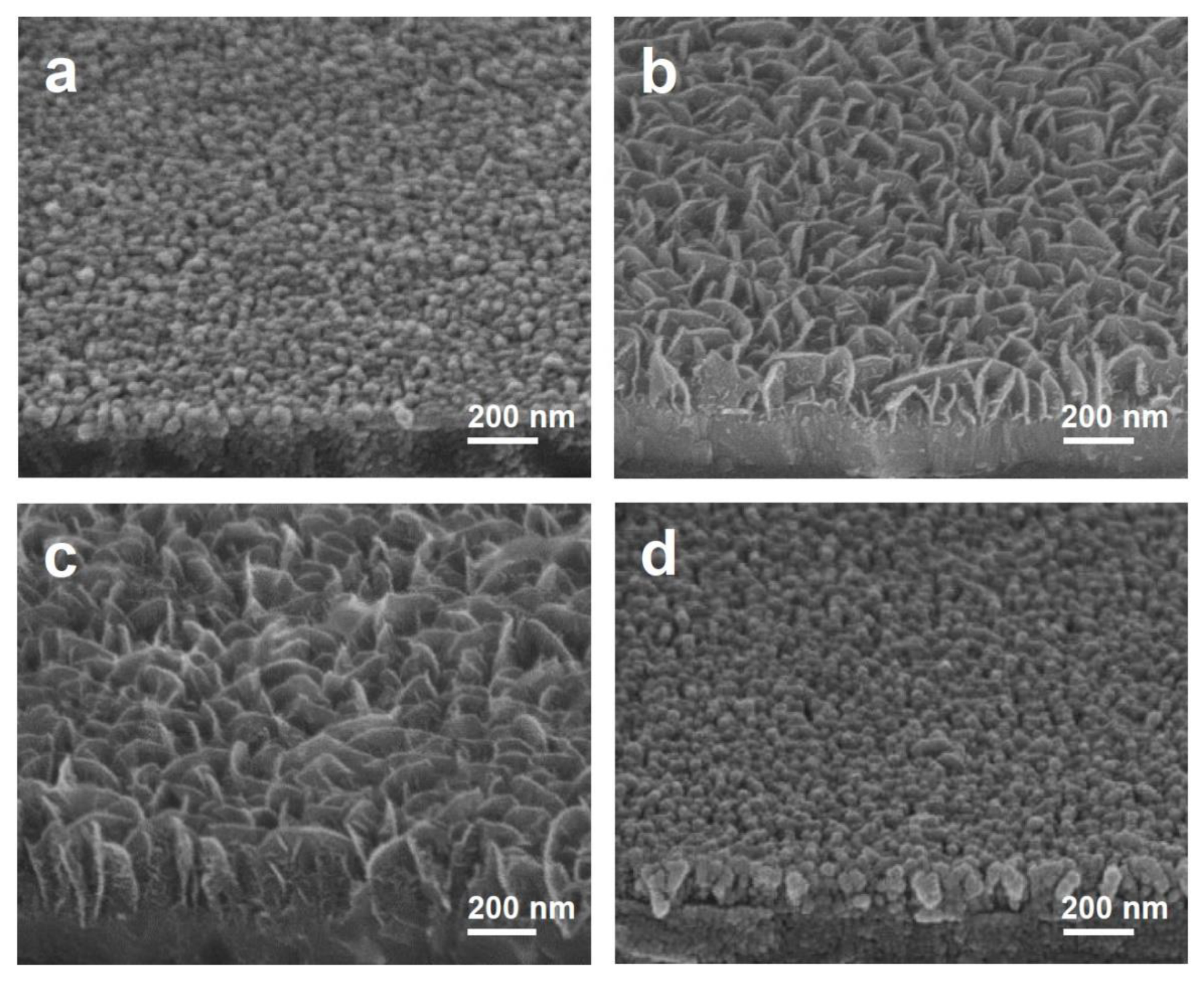

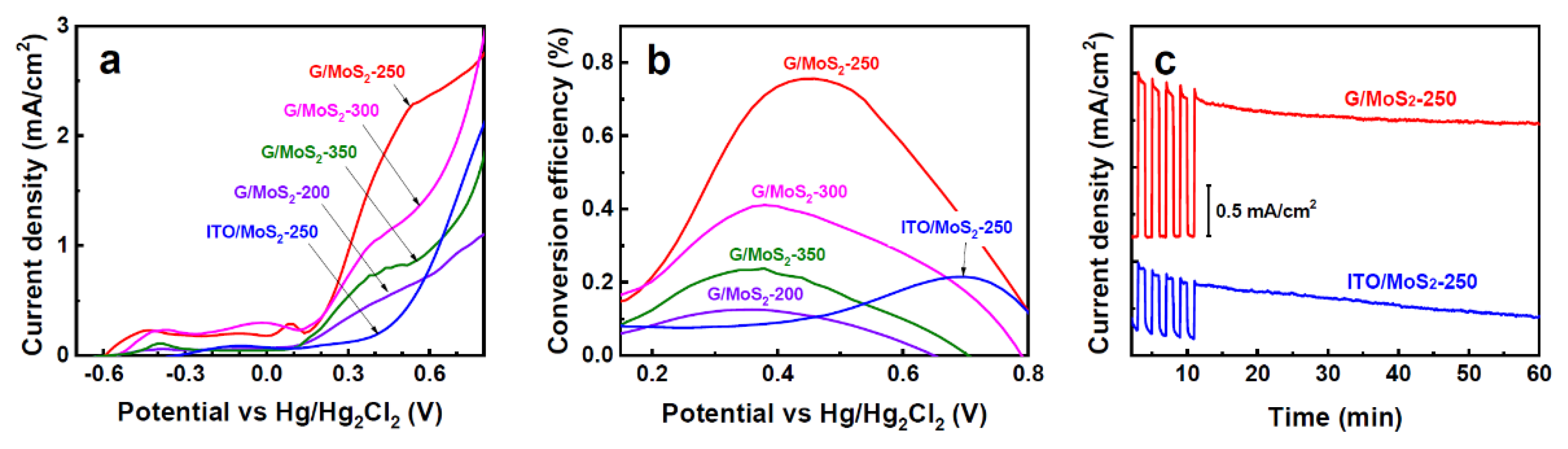

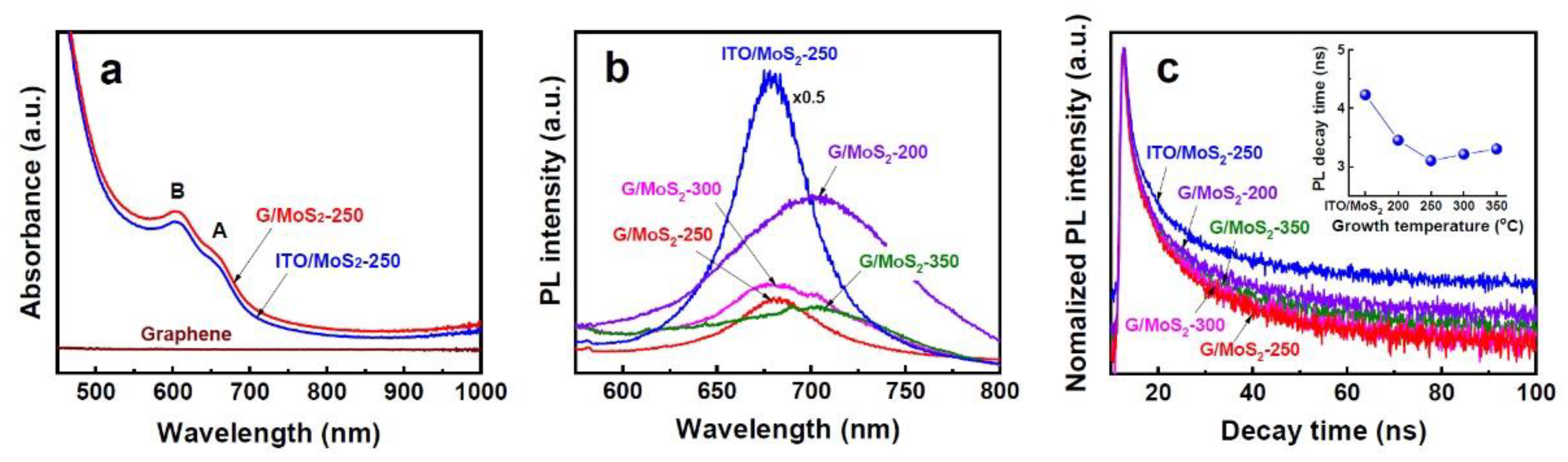

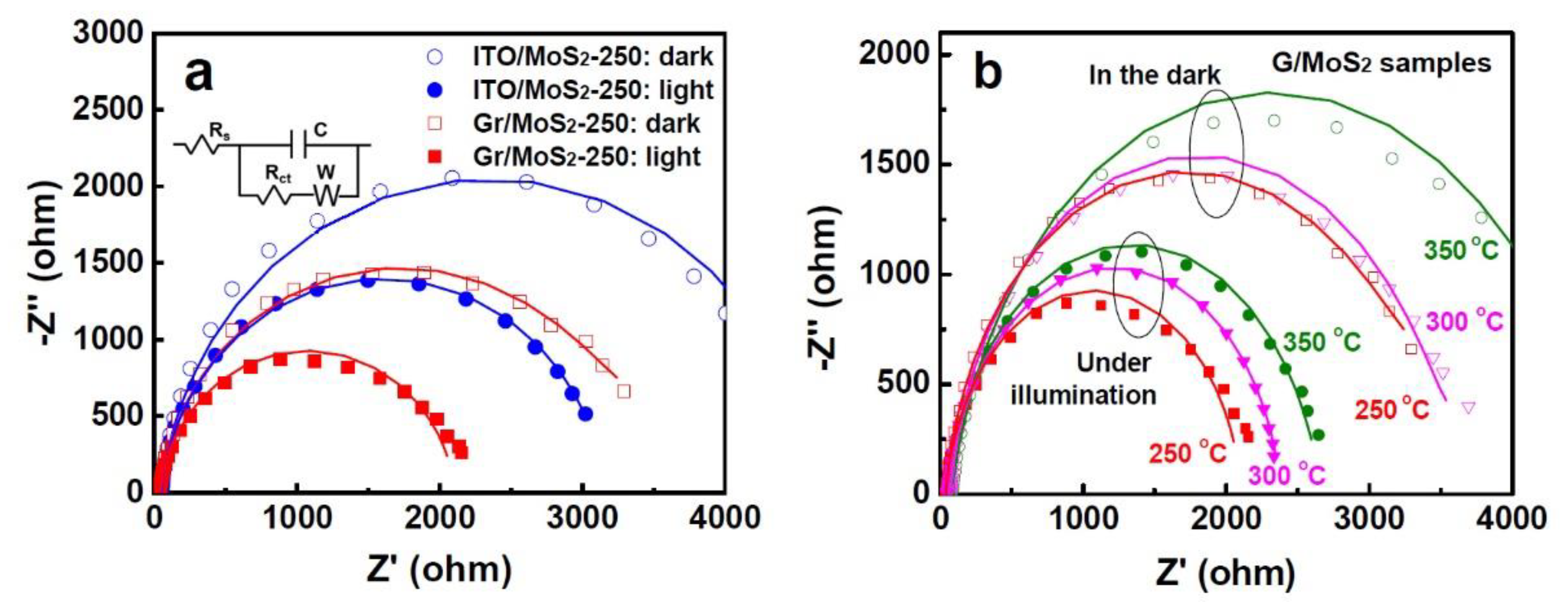

3. Results and Discussion

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhou, M.; Lou, X.W.; Xie, Y. Two-dimensional nanosheets for photoelectrochemical water splitting: Possibilities and opportunities. Nano Today 2013, 8, 598–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faraji, M.; Yousefi, M.; Yousefzadeh, S.; Zirak, M.; Naseri, N.; Jeon, T.H.; Choi, W.; Moshfegh, A.Z. Two-dimensional materials in semiconductor photoelectrocatalytic systems for water splitting. Energy Environ. Sci. 2019, 12, 59–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Q.; Song, B.; Xu, P.; Jin, S. Efficient electrocatalytic and photoelectrochemical hydrogen generation using MoS2 and related compounds. Chem 2016, 1, 699–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Han, B.; Hu, Y.H. MoS2 as a co-catalyst for photocatalytic hydrogen production from water. Energy Sci. Eng. 2016, 4, 285–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chen, B.; Meng, Y.; Sha, J.; Zhong, C.; Hu, W.; Zhao, N. Preparation of MoS2/TiO2 based nanocomposites for photocatalysis and rechargeable batteries: Progress, challenges, and perspective. Nanoscale 2018, 10, 34–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamouchi, A.; Assaker, I.B.; Chtourou, R. Enhanced photoelectrochemical activity of MoS2-decorated ZnO nanowires electrodeposited onto stainless steel mesh for hydrogen production. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2019, 478, 937–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Yu, Y.X.; Zhang, W.D. MoS2/CdS heterojunction with high photoelectrochemical activity for H2 evolution under visible light: The role of MoS2. J. Phys. Chem. C 2013, 117, 12949–12957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trung, T.N.; Seo, D.B.; Quang, N.D.; Kim, D.; Kim, E.T. Enhanced photoelectrochemical activity in the heterostructure of vertically aligned few-layer MoS2 flakes on ZnO. Electrochim. Acta 2018, 260, 150–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pi, Y.; Li, Z.; Xu, D.; Liu, J.; Li, Y.; Zhang, F.; Zhang, G.; Peng, W.; Fan, X. 1T-phase MoS2 nanosheets on TiO2 nanorod arrays: 3D photoanode with extraordinary catalytic performance. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2017, 5, 5175–5182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Han, W.; Tang, H.; Ren, L.; Chander, D.S.; Qi, X.; Zhang, H. Photoelectrochemical-type sunlight photodetector based on MoS2/graphene heterostructure. 2D Mater. 2015, 2, 035011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carraro, F.; Calvillo, L.; Cattelan, M.; Favaro, M.; Righetto, M.; Nappini, S.; Píš, I.; Celorrio, V.; Fermín, D.J.; Martucci, A.; et al. Fast one-pot synthesis of MoS2/crumpled graphene p–n nanonjunctions for enhanced photoelectrochemical hydrogen production. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2015, 7, 25685–25692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geim, A.K.; Novoselov, K.S. The rise of graphene. Nat. Mater. 2007, 6, 183–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, K.; Mei, Z.; Wang, T.; Kang, Q.; Ouyang, S.; Ye, J. MoS2/graphene cocatalyst for efficient photocatalytic H2 evolution under visible light irradiation. ACS Nano 2014, 8, 7078–7087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Du, R.; Li, B.; Zhanga, Y.; Liu, H.; Qu, J.; An, X. Biomolecule-assisted self-assembly of CdS/MoS2/graphene hollowspheres as high-efficiency photocatalysts for hydrogen evolution without noble metals. Appl. Catal. B 2016, 182, 504–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Du, J.; Wang, Z.; Luo, M.; Tian, Y.; Fujita, T.; Xue, Q.; Chen, M. Three-dimensional nanoporous heterojunction of monolayer MoS2@rGO for photoenhanced hydrogen evolution reaction. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 2018, 1, 2183−2191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, H.; Lin, J.; Fu, W.; Wang, X.; Wang, H.; Zeng, Q.; Gu, Q.; Li, Y.; Yan, C.; Tay, B.K.; et al. MoS2/TiO2 edge-on heterostructure for efficient photocatalytic hydrogen evolution. Adv. Energy Mater. 2016, 6, 1600464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, D.B.; Trung, T.N.; Kim, D.O.; Duc, D.V.; Hong, S.; Sohn, Y.; Jeong, J.R.; Kim, E.T. Plasmonic Ag-decorated few-layer MoS2 nanosheets vertically grown on graphene for efficient photoelectrochemical water splitting. Nano Micro Lett. 2020, 12, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, D.B.; Kim, S.; Trung, T.N.; Kim, D.; Kim, E.T. Conformal growth of few-layer MoS2 flakes on closely-packed TiO2 nanowires and their enhanced photoelectrochemical reactivity. J. Alloys Compd. 2019, 770, 686–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Z.; Zhu, W.; Yu, X.; Zhang, H.; Li, Y.; Sun, X.; Wang, X.; Wang, H.; Wang, J.; Luo, J.; et al. Ultrahigh hydrogen evolution performance of under-water “Superaerophobic” MoS2 nanostructured electrodes. Adv. Mater. 2014, 26, 2683–2687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, C.; Yan, H.; Brus, L.E.; Heinz, T.F.; Hone, J.; Ryu, S. Anomalous lattice vibrations of single- and few-layer MoS2. ACS Nano 2010, 4, 2695–2700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Li, H.; Zhang, Q.; Yap, C.C.R.; Tay, B.K.; Edwin, T.H.T.; Olivier, A.; Baillargeat, D. From bulk to monolayer MoS2: Evolution of raman scattering. Adv. Funct. Mater 2012, 22, 1385–1390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mak, K.F.; Lee, C.; Hone, J.; Shan, J.; Heinz, T.F. Atomically thin MoS2: A new direct-gap semiconductor. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2010, 105, 136805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Velický, M.; Bissett, M.A.; Woods, C.R.; Toth, P.S.; Georgiou, T.; Kinloch, I.A.; Novoselov, K.S.; Dryfe, R.A.W. Photoelectrochemistry of pristine mono- and few-layer MoS2. Nano Lett. 2016, 16, 2023–2032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Nang, L.V.; Kim, E.T. Controllable synthesis of high-quality graphene using inductively coupled plasma chemical vapor deposition. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2012, 159, K93−K96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, K.; Xie, S.; Huang, L.; Han, Y.; Huang, P.Y.; Mak, K.F.; Kim, C.J.; Muller, D.; Park, J. High-mobility three-atom-thick semiconducting films with wafer-scale homogeneity. Nature 2015, 520, 656–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.H.; Zhang, X.Q.; Zhang, W.; Chang, M.T.; Lin, C.T.; Chang, K.D.; Yu, Y.C.; Wang, J.T.W.; Chang, C.S.; Li, L.J.; et al. Synthesis of large-area MoS2 atomic layers with chemical vapor deposition. Adv. Mater. 2012, 24, 2320–2325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Jeon, J.; Jang, S.K.; Jeon, S.M.; Yoo, G.; Jang, Y.H.; Park, J.H.; Lee, S. Layer-controlled CVD growth of large-area two-dimensional MoS2 films. Nanoscale 2015, 7, 1688–1695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yim, C.; O’Brien, M.; McEvoy, N.; Winters, S.; Mirza, I.; Lunney, J.G.; Duesberg, G.S. Investigation of the optical properties of MoS2 thin films using spectroscopic ellipsometry. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2014, 104, 103114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dong, J.; Zhang, X.; Huang, J.; Gao, S.; Mao, J.; Cai, J.; Chen, Z.; Sathasivam, S.; Carmalt, C.J.; Lai, Y. Boosting heterojunction interaction in electrochemical construction of MoS2 quantum dots@TiO2 nanotube arrays for highly effective photoelectrochemical performance and electrocatalytic hydrogen evolution. Electrochem. Commun. 2018, 93, 152–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Zhang, S.; Song, Q.; Yan, H.; Kang, J.; Guo, Y.; Liu, Z. The synergistic effect with S-vacancies and built-in electric field on a TiO2/MoS2 photoanode for enhanced photoelectrochemical performance. Sustain. Energy Fuels 2021, 5, 509–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karmakar, K.; Maity, D.; Pal, D.; Mandal, K.; Khan, G.G. Photo-induced exciton dynamics and broadband light harvesting in ZnO nanorod-templated multilayered two-dimensional MoS2/MoO3 photoanodes for solar fuel generation. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2020, 3, 1223−1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sitara, E.; Nasir, H.; Mumtaz, A.; Ehsan, M.F.; Sohail, M.; Iram, S.; Bukhari, S.A.B. Efficient photoelectrochemical water splitting by tailoring MoS2/CoTe heterojunction in a photoelectrochemical cell. Nanomaterials 2020, 10, 2341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masoumi, Z.; Tayebi, M.; Lee, B.K. Ultrasonication-assisted liquid-phase exfoliation enhances photoelectrochemical performance in α-Fe2O3/MoS2 photoanode. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2021, 72, 105403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eda, G.; Yamaguchi, H.; Voiry, D.; Fujita, T.; Chen, M.; Chhowalla, M. Photoluminescence from chemically exfoliated MoS2. Nano Lett. 2011, 11, 5111–5116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Major, J.D.; Al Turkestani, M.; Bowen, L.; Brossard, M.; Li, C.; Lagoudakis, P.; Pennycook, S.J.; Phillips, L.J.; Treharne, R.E.; Durose, K. In-depth analysis of chloride treatments for thin-film CdTe solar cells. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 13231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lee, H.; Deshmukh, S.; Wen, J.; Costa, V.Z.; Schuder, J.S.; Sanchez, M.; Ichimura, A.A.; Pop, E.; Wang, B.; Newqaz, A.K.M. Layer-dependent interfacial transport and optoelectrical properties of MoS2 on ultraflat metals. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2019, 11, 31543−31550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Yu, Y.J.; Zhao, Y.; Ryu, S.; Brus, L.E.; Kim, K.S.; Kim, P. Tuning the graphene work function by electric field effect. Nano Lett. 2009, 9, 3430–3434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Seo, D.-B.; Trung, T.N.; Bae, S.-S.; Kim, E.-T. Improved Photoelectrochemical Performance of MoS2 through Morphology-Controlled Chemical Vapor Deposition Growth on Graphene. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 1585. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano11061585

Seo D-B, Trung TN, Bae S-S, Kim E-T. Improved Photoelectrochemical Performance of MoS2 through Morphology-Controlled Chemical Vapor Deposition Growth on Graphene. Nanomaterials. 2021; 11(6):1585. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano11061585

Chicago/Turabian StyleSeo, Dong-Bum, Tran Nam Trung, Sung-Su Bae, and Eui-Tae Kim. 2021. "Improved Photoelectrochemical Performance of MoS2 through Morphology-Controlled Chemical Vapor Deposition Growth on Graphene" Nanomaterials 11, no. 6: 1585. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano11061585