Heterostructures of Cut Carbon Nanotube-Filled Array of TiO2 Nanotubes for New Module of Photovoltaic Devices

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Fabrication of TiO2-NTs

2.2. Cutting of the MWCNTs

2.3. Preparation of the Heterostructure of TiO2-NTs@cut-MWCNTs

2.4. Fabrication of All-Titanium–Carbon Photovoltaic Device

2.5. Characterization

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Characterizations of Cut-MWCNTs

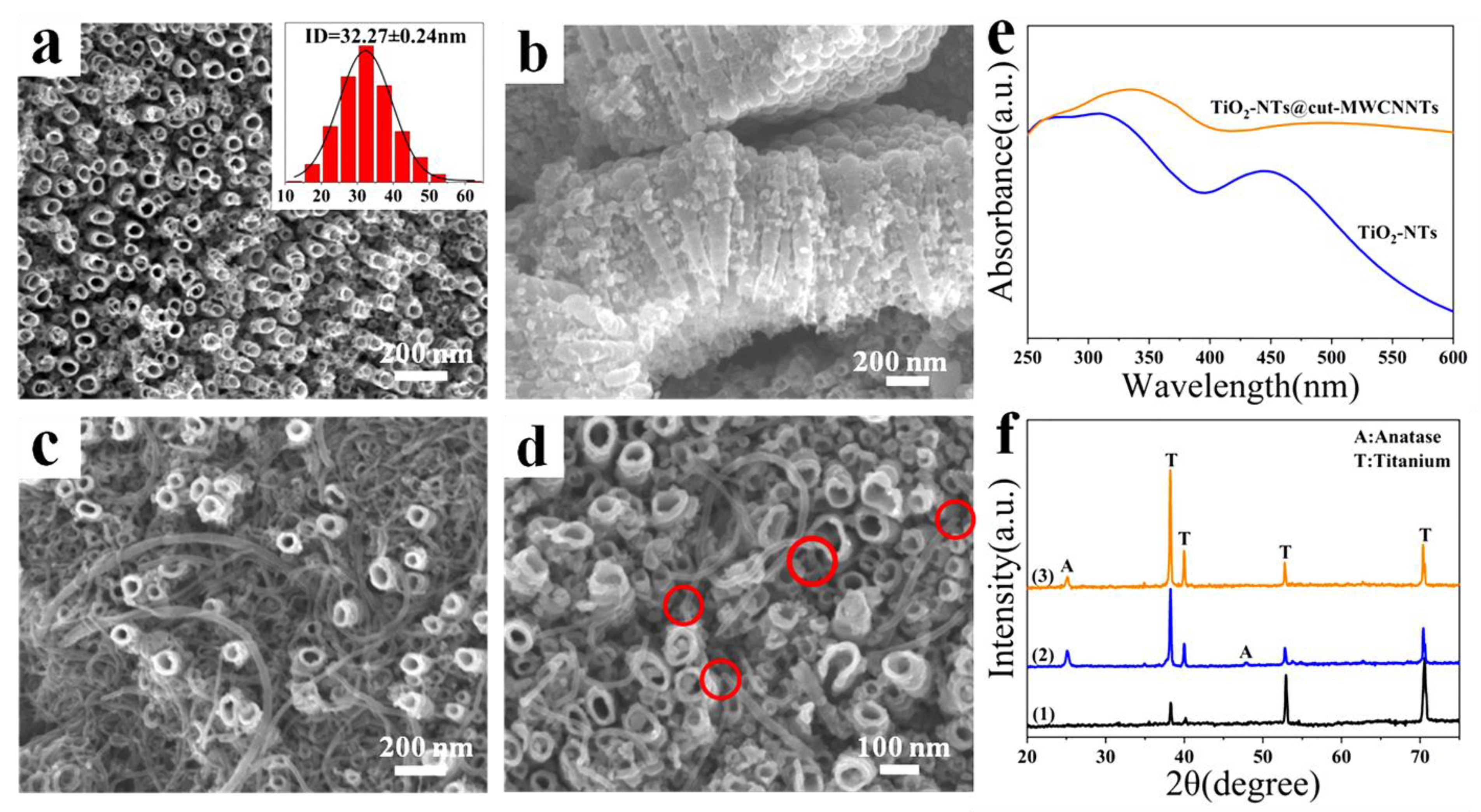

3.2. Characterizations of TiO2-NTs@cut-MWCNT Heterostructure

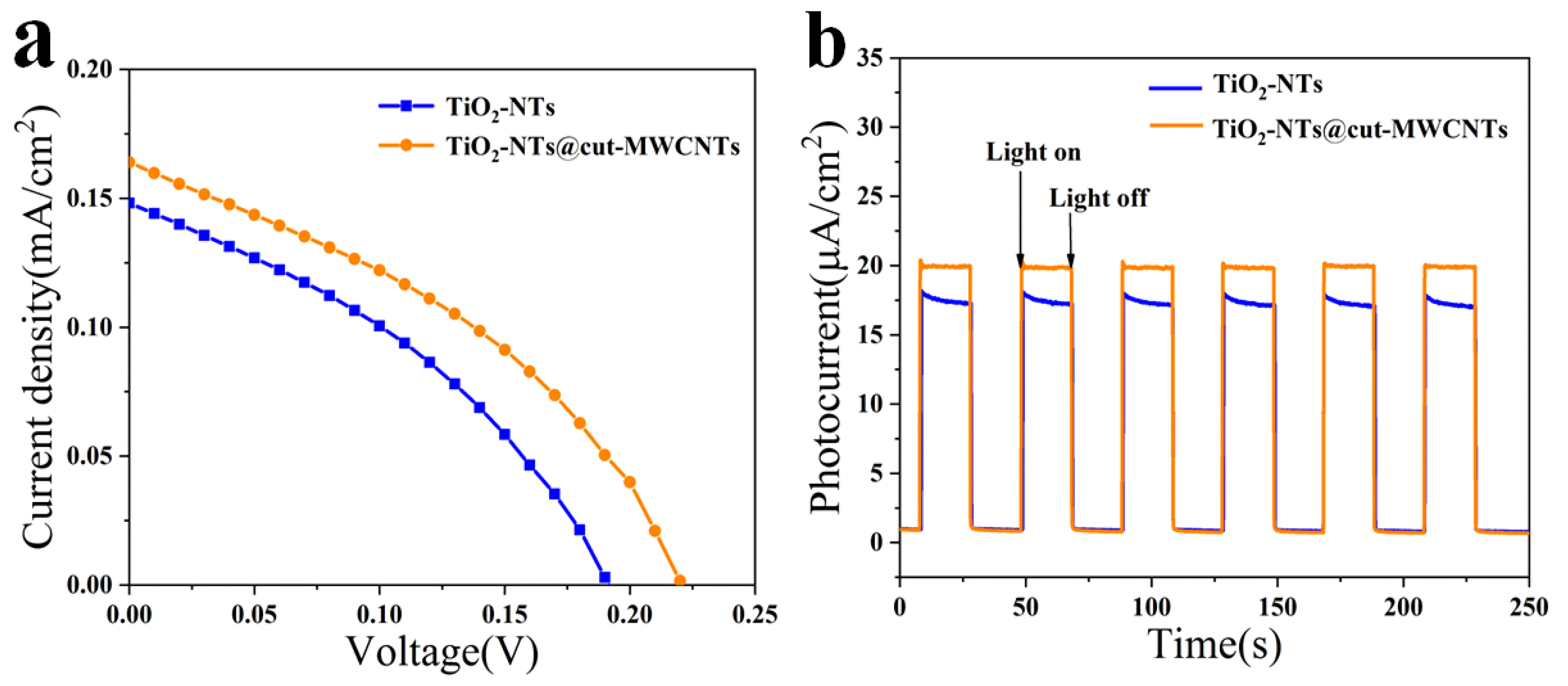

3.3. Characterizations of All-Titanium–Carbon Photovoltaic Device

3.4. Mechanism of Photocurrent Generation

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lewis, N.S. Toward cost-effective solar energy use. Science 2007, 315, 798–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, C.W. 2-Layer Organic Photovoltaic Cell. Appl. Phys. Lett. 1986, 48, 183–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oregan, B.; Gratzel, M. A Low-Cost, High-Efficiency Solar-Cell Based on Dye-Sensitized Colloidal TiO2 Films. Nature 1991, 353, 737–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariotti, N.; Bonomo, M.; Fagiolari, L.; Barbero, N.; Gerbaldi, C.; Bella, F.; Barolo, C. Recent advances in eco-friendly and cost-effective materials towards sustainable dye-sensitized solar cells. Green Chem. 2020, 22, 7168–7218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, D.; Grimes, C.A.; Varghese, O.K.; Hu, W.C.; Singh, R.S.; Chen, Z.; Dickey, E.C. Titanium oxide nanotube arrays prepared by anodic oxidation. J. Mater. Res. 2001, 16, 3331–3334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paulose, M.; Shankar, K.; Varghese, O.K.; Mor, G.K.; Hardin, B.; Grimes, C.A. Backside illuminated dye-sensitized solar cells based on titania nanotube array electrodes. Nanotechnology 2006, 17, 1446–1448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, S.; Ha, N.L.C.; Rothenberger, G.; Liska, P.; Comte, P.; Zakeeruddin, S.M.; Pechy, P.; Nazeeruddin, M.K.; Gratzel, M. High-efficiency (7.2%) flexible dye-sensitized solar cells with Ti-metal substrate for nanocrystalline-TiO2 photoanode. Chem. Commun. 2006, 4004–4006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.H.; Xiao, Y.M.; Tang, Q.W.; Yue, G.T.; Lin, J.M.; Huang, M.L.; Huang, Y.F.; Fan, L.Q.; Lan, Z.; Yin, S.; et al. A Large-Area Light-Weight Dye-Sensitized Solar Cell based on All Titanium Substrates with an Efficiency of 6.69% Outdoors. Adv. Mater. 2012, 24, 1884–1888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyein, N.; Tan, W.K.; Kawamura, G.; Matsuda, A.; Lockman, Z. TiO2 nanotube arrays formation in fluoride/ethylene glycol electrolyte containing LiOH or KOH as photoanode for dye-sensitized solar cell. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A-Chem. 2017, 343, 33–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, W.; Qiu, J.J.; Zhuge, F.W.; Li, X.M.; Lee, J.H.; Kim, Y.D.; Kim, H.K.; Hwang, Y.H. Advantages of using Ti-mesh type electrodes for flexible dye-sensitized solar cells. Nanotechnology 2012, 23, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zha, C.Y.; Shen, L.M.; Zhang, X.Y.; Wang, Y.F.; Korgel, B.A.; Gupta, A.; Bao, N.Z. Double-Sided Brush-Shaped TiO2 Nanostructure Assemblies with Highly Ordered Nanowires for Dye-Sensitized Solar Cells. Acs Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2014, 6, 122–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castrucci, P.; Scilletta, C.; Del Gobbo, S.; Scarselli, M.; Camilli, L.; Simeoni, M.; Delley, B.; Continenza, A.; De Crescenzi, M. Light harvesting with multiwall carbon nanotube/silicon heterojunctions. Nanotechnology 2011, 22, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castrucci, P.; Tombolini, F.; Scarselli, M.; Speiser, E.; Del Gobbo, S.; Richter, W.; De Crescenzi, M.; Diociaiuti, M.; Gatto, E.; Venanzi, M. Large photocurrent generation in multiwall carbon nanotubes. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2006, 89, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Khakani, M.A.; Le Borgne, V.; Aissa, B.; Rosei, F.; Scilletta, C.; Speiser, E.; Scarselli, M.; Castrucci, P.; De Crescenzi, M. Photocurrent generation in random networks of multiwall-carbon-nanotubes grown by an “all-laser” process. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2009, 95, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scarselli, M.; Scilletta, C.; Tombolini, F.; Castrucci, P.; De Crescenzi, M.; Diociaiuti, M.; Casciardi, S.; Gatto, E.; Venanzi, M. Photon harvesting with multi wall carbon nanotubes. Superlattices Microstruct. 2009, 46, 340–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Scarselli, M.; Scilletta, C.; Tombolini, F.; Castrucci, P.; Diociaiuti, M.; Casciardi, S.; Gatto, E.; Venanzi, M.; De Crescenzi, M. Multiwall Carbon Nanotubes Decorated with Copper Nanoparticles: Effect on the Photocurrent Response. J. Phys. Chem. C 2009, 113, 5860–5864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarker, B.K.; Arif, M.; Stokes, P.; Khondaker, S.I. Diffusion mediated photoconduction in multiwalled carbon nanotube films. J. Appl. Phys. 2009, 106, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ou, Y.; Lin, J.D.; Fang, S.M.; Liao, D.W. MWNT-TiO2: Ni composite catalyst: A new class of catalyst for photocatalytic H-2 evolution from water under visible light illumination. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2006, 429, 199–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kierkowicz, M.; Pach, E.; Santidrian, A.; Sandoval, S.; Goncalves, G.; Tobias-Rossell, E.; Kalbac, M.; Ballesteros, B.; Tobias, G. Comparative study of shortening and cutting strategies of single-walled and multi-walled carbon nanotubes assessed by scanning electron microscopy. Carbon 2018, 139, 922–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.S.; Vairam, S.; Neelakandeswari, N.; Aruna, S. Effect of metal oxide charge transfer layers on the photovoltaic performance of carbon nanotube heterojunction solar cells. Mater. Lett. 2018, 220, 249–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalita, G.; Adhikari, S.; Aryal, H.R.; Umeno, M.; Afre, R.; Soga, T.; Sharon, M. Cutting carbon nanotubes for solar cell application. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2008, 92, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, B.A.; Zhang, H.; Cha, T.G.; Choi, J.H. 9—Carbon nanotube solar cells. In Carbon Nanotubes and Graphene for Photonic Applications; Yamashita, S., Saito, Y., Choi, J.H., Eds.; Woodhead Publishing: Sawston, UK, 2013; pp. 241–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macak, J.M.; Gong, B.G.; Hueppe, M.; Schmuki, P. Filling of TiO2 Nanotubes by Self-Doping and Electrodeposition. Adv. Mater. 2007, 19, 3027–3031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, M.R.; Martin, S.T.; Choi, W.; Bahnemann, D.W. Environmental Applications of Semiconductor Photocatalysis. Chem. Rev. 1995, 95, 69–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Serp, P.; Kalck, P.; Faria, J. Visible Light Photodegradation of Phenol on MWNT-TiO2 Composite Catalysts Prepared by a Modified Sol–Gel Method. J. Mol. Catal. A Chem. 2005, 235, 194–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, S.; Wong, S. Synthesis and Characterization of Carbon Nanotube−Nanocrystal Heterostructures. Nano Lett.-NANO LETT 2002, 2, 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, B.Z.; Wang, S.C.; Yang, W.B.; Wang, Y.; Huang, L.J.; Popat, K.C.; Kipper, M.J.; Belfiore, L.A.; Tang, J.G. Synthesis of Eu-modified luminescent Titania nanotube arrays and effect of voltage on morphological, structural and spectroscopic properties. Mater. Sci. Semicond. Process. 2020, 113, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, H.J. Carbon nanotubes: Opportunities and challenges. Surf. Sci. 2002, 500, 218–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.P.; Feng, M.; Zhan, H.B. Electrochemistry of partially unzipped carbon nanotubes. Electrochem. Commun. 2014, 45, 95–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saito, T.; Matsushige, K.; Tanaka, K. Chemical treatment and modification of multi-walled carbon nanotubes. Phys. B 2002, 323, 280–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Wang, Y.; Wang, D.; Wei, F. Characterization of single-wall carbon nanotubes by N2 adsorption. Carbon 2004, 42, 2375–2383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iijima, S. Helical Microtubules of Graphitic Carbon. Nature 1991, 354, 56–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes-Coronado, D.; Rodríguez-Gattorno, G.; Espinosa-Pesqueira, M.E.; Cab, C.; de Coss, R.; Oskam, G. Phase-pure TiO2nanoparticles: Anatase, brookite and rutile. Nanotechnology 2008, 19, 145605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, J.W.; Liang, J.; Sumathy, K. Review on dye-sensitized solar cells (DSSCs): Fundamental concepts and novel materials. Renew. Sust. Energ. Rev. 2012, 16, 5848–5860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boukhvalov, D.W.; Katsnelson, M.I. Modeling of graphite oxide. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008, 130, 10697–10701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, D.H.; Choi, D.W.; Li, J.; Yang, Z.G.; Nie, Z.M.; Kou, R.; Hu, D.H.; Wang, C.M.; Saraf, L.V.; Zhang, J.G.; et al. Self-Assembled TiO2-Graphene Hybrid Nanostructures for Enhanced Li-Ion Insertion. ACS Nano 2009, 3, 907–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.S.; Sprinkle, M.; Li, X.B.; Ming, F.; Berger, C.; de Heer, W.A. Epitaxial-graphene/graphene-oxide junction: An essential step towards epitaxial graphene electronics. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2008, 101, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilje, S.; Han, S.; Wang, M.; Wang, K.L.; Kaner, R.B. A chemical route to graphene for device applications. Nano Lett. 2007, 7, 3394–3398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, T.F.; Chan, F.F.; Hsieh, C.T.; Teng, H.S. Graphite Oxide with Different Oxygenated Levels for Hydrogen and Oxygen Production from Water under Illumination: The Band Positions of Graphite Oxide. J. Phys. Chem. C 2011, 115, 22587–22597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sample | C [%] | O [%] | N [%] | S [%] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MWCNTs | 95.7 | 4.3 | -- | -- |

| cut-MWCNTs | 82.55 | 15.46 | 1.57 | 0.42 |

| Sample | Voc (V) | Jsc (mA/cm2) | FF [%] | PCE [%] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TiO2-NTs | 0.19 | 0.148 | 0.365 | 0.01036 |

| TiO2-NTs@cut-MWCNTs | 0.22 | 0.164 | 0.381 | 0.01380 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Niu, S.; Yang, W.; Wei, H.; Danilov, M.; Rusetskyi, I.; Popat, K.C.; Wang, Y.; Kipper, M.J.; Belfiore, L.A.; Tang, J. Heterostructures of Cut Carbon Nanotube-Filled Array of TiO2 Nanotubes for New Module of Photovoltaic Devices. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 3604. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano12203604

Niu S, Yang W, Wei H, Danilov M, Rusetskyi I, Popat KC, Wang Y, Kipper MJ, Belfiore LA, Tang J. Heterostructures of Cut Carbon Nanotube-Filled Array of TiO2 Nanotubes for New Module of Photovoltaic Devices. Nanomaterials. 2022; 12(20):3604. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano12203604

Chicago/Turabian StyleNiu, Siqi, Wenbin Yang, Heng Wei, Michail Danilov, Ihor Rusetskyi, Ketul C. Popat, Yao Wang, Matt J. Kipper, Laurence A. Belfiore, and Jianguo Tang. 2022. "Heterostructures of Cut Carbon Nanotube-Filled Array of TiO2 Nanotubes for New Module of Photovoltaic Devices" Nanomaterials 12, no. 20: 3604. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano12203604

APA StyleNiu, S., Yang, W., Wei, H., Danilov, M., Rusetskyi, I., Popat, K. C., Wang, Y., Kipper, M. J., Belfiore, L. A., & Tang, J. (2022). Heterostructures of Cut Carbon Nanotube-Filled Array of TiO2 Nanotubes for New Module of Photovoltaic Devices. Nanomaterials, 12(20), 3604. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano12203604