Majorana Excitons in a Kitaev Chain of Semiconductor Quantum Dots in a Nanowire

Abstract

:1. Introduction

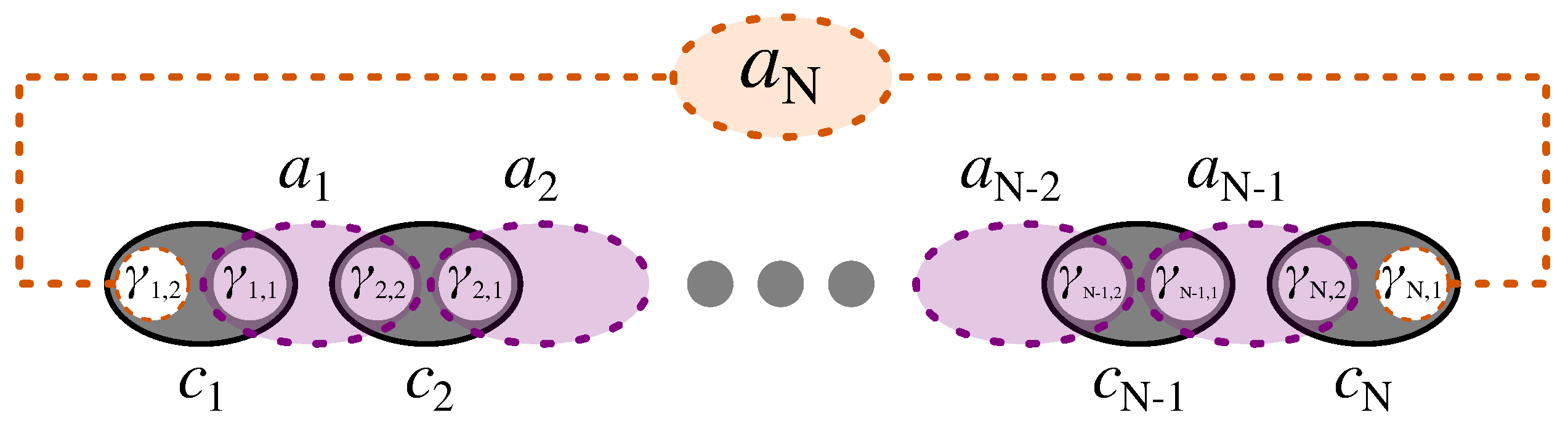

2. Kitaev Chain in a Semiconductor Nanowire

3. Majorana and Bond Fermions in Kitaev Hamiltonian

3.1. Exact Diagonalization in Normal Fermion Basis

3.2. Bond Fermions

3.3. Energy Spectrum

4. Kitaev Chain and a Light Induced Valence Hole

4.1. Exact Diagonalization of Electron–Hole System

4.2. Energy Spectrum of the Electron–Hole System

4.3. Absorption Spectrum

4.3.1. Analytic Result for Localized Hole

4.3.2. Absorption for Mobile Hole

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Exact Diagonalization for Chain of Length Three

Appendix B. Analytic Calculation of Absorption Spectrum for Localized Hole

References

- Gyongyosi, L.; Imre, S. A survey on quantum computing technology. Comput. Sci. Rev. 2019, 31, 51–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Field, B.; Simula, T. Introduction to topological quantum computation with non-Abelian anyons. Quantum Sci. Technol. 2018, 3, 045004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Campbell, E.T.; Terhal, B.M.; Vuillot, C. Roads towards fault-tolerant universal quantum computation. Nature 2017, 549, 172–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Stern, A.; Lindner, N.H. Topological quantum computation—From basic concepts to first experiments. Science 2013, 339, 1179–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nayak, C.; Simon, S.H.; Stern, A.; Freedman, M.; Sarma, S.D. Non-Abelian anyons and topological quantum computation. Rev. Mod. Phys. 2008, 80, 1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sarma, S.D.; Freedman, M.; Nayak, C. Majorana zero modes and topological quantum computation. NPJ Quantum Inf. 2015, 1, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Das Sarma, S.; Freedman, M.; Nayak, C. Topological quantum computation. Phys. Today 2006, 59, 32–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freedman, M.; Kitaev, A.; Larsen, M.; Wang, Z. Topological quantum computation. Bull. Am. Math. Soc. 2002, 40, 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jaworowski, B.; Hawrylak, P. Quantum bits with macroscopic topologically protected states in semiconductor devices. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Haldane, F.D.M. Nonlinear field theory of large-spin Heisenberg antiferromagnets: Semiclassically quantized solitons of the one-dimensional easy-axis Néel state. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1983, 50, 1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitaev, A.Y. Unpaired Majorana fermions in quantum wires. Physics-Uspekhi 2001, 44, 131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitaev, A.Y. Fault-tolerant quantum computation by anyons. Ann. Phys. 2003, 303, 2–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lutchyn, R.M.; Sau, J.D.; Sarma, S.D. Majorana fermions and a topological phase transition in semiconductor-superconductor heterostructures. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2010, 105, 077001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Mourik, V.; Zuo, K.; Frolov, S.M.; Plissard, S.; Bakkers, E.P.; Kouwenhoven, L.P. Signatures of Majorana fermions in hybrid superconductor-semiconductor nanowire devices. Science 2012, 336, 1003–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Sau, J.D.; Sarma, S.D. Realizing a robust practical Majorana chain in a quantum-dot-superconductor linear array. Nat. Commun. 2012, 3, 964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Leijnse, M.; Flensberg, K. Parity qubits and poor man’s Majorana bound states in double quantum dots. Phys. Rev. B 2012, 86, 134528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dvir, T.; Wang, G.; van Loo, N.; Liu, C.X.; Mazur, G.P.; Bordin, A.; Ten Haaf, S.L.; Wang, J.Y.; van Driel, D.; Zatelli, F.; et al. Realization of a minimal Kitaev chain in coupled quantum dots. Nature 2023, 614, 445–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nadj-Perge, S.; Drozdov, I.K.; Li, J.; Chen, H.; Jeon, S.; Seo, J.; MacDonald, A.H.; Bernevig, B.A.; Yazdani, A. Observation of Majorana fermions in ferromagnetic atomic chains on a superconductor. Science 2014, 346, 602–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sun, H.H.; Jia, J.F. Detection of Majorana zero mode in the vortex. NPJ Quantum Mater. 2017, 2, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Liu, D.E.; Baranger, H.U. Detecting a Majorana-fermion zero mode using a quantum dot. Phys. Rev. B 2011, 84, 201308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jäck, B.; Xie, Y.; Yazdani, A. Detecting and distinguishing Majorana zero modes with the scanning tunnelling microscope. Nat. Rev. Phys. 2021, 3, 541–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pientka, F.; Romito, A.; Duckheim, M.; Oreg, Y.; von Oppen, F. Signatures of topological phase transitions in mesoscopic superconducting rings. New J. Phys. 2013, 15, 025001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pikulin, D.I.; van Heck, B.; Karzig, T.; Martinez, E.A.; Nijholt, B.; Laeven, T.; Winkler, G.W.; Watson, J.D.; Heedt, S.; Temurhan, M.; et al. Protocol to identify a topological superconducting phase in a three-terminal device. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2103.12217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Potter, A.C.; Law, K.T.; Lee, P.A. Zero-bias peaks in the tunneling conductance of spin-orbit-coupled superconducting wires with and without Majorana end-states. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2012, 109, 267002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Sarma, S.D.; Pan, H. Disorder-induced zero-bias peaks in Majorana nanowires. Phys. Rev. B 2021, 103, 195158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubbert, S.; Akhmerov, A. Detecting Majorana nonlocality using strongly coupled Majorana bound states. Phys. Rev. 2016, 94, 115430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Aghaee, M.; Akkala, A.; Alam, Z.; Ali, R.; Ramirez, A.A.; Andrzejczuk, M.; Antipov, A.E.; Astafev, M.; Bauer, B.; Becker, J.; et al. InAs-Al hybrid devices passing the topological gap protocol. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2207.02472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldelli, N.; Bhattacharya, U.; González-Cuadra, D.; Lewenstein, M.; Graß, T. Detecting Majorana zero modes via strong field dynamics. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 47424–47430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cygorek, M.; Korkusinski, M.; Hawrylak, P. Atomistic theory of electronic and optical properties of InAsP/InP nanowire quantum dots. Phys. Rev. B 2020, 101, 075307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Manalo, J.; Cygorek, M.; Altintas, A.; Hawrylak, P. Electronic and magnetic properties of many-electron complexes in charged InAsxP1−x quantum dots in InP nanowires. Phys. Rev. B 2021, 104, 125402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koong, Z.X.; Ballesteros-Garcia, G.; Proux, R.; Dalacu, D.; Poole, P.J.; Gerardot, B.D. Multiplexed single photons from deterministically positioned nanowire quantum dots. Phys. Rev. Appl. 2020, 14, 034011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalacu, D.; Mnaymneh, K.; Lapointe, J.; Wu, X.; Poole, P.J.; Bulgarini, G.; Zwiller, V.; Reimer, M.E. Ultraclean emission from InAsP quantum dots in defect-free wurtzite InP nanowires. Nano Lett. 2012, 12, 5919–5923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaworowski, B.; Rogers, N.; Grabowski, M.; Hawrylak, P. Macroscopic singlet-triplet qubit in synthetic spin-one chain in semiconductor nanowires. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 5529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Phoenix, J.; Korkusinski, M.; Dalacu, D.; Poole, P.J.; Zawadzki, P.; Studenikin, S.; Williams, R.L.; Sachrajda, A.S.; Gaudreau, L. Magnetic tuning of tunnel coupling between InAsP double quantum dots in InP nanowires. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 5100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Northeast, D.B.; Weber, J.F.; Dalacu, D.; Phoenix, J.; Poole, P.J.; Aers, G.; Lapointe, J.; Williams, R.L. Optical fibre-based (plug-and-play) single photon source using InAsP quantum dot nanowires and gradient-index lens collection. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2104.11197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laferrière, P.; Yeung, E.; Korkusinski, M.; Poole, P.J.; Williams, R.L.; Dalacu, D.; Manalo, J.; Cygorek, M.; Altintas, A.; Hawrylak, P. Systematic study of the emission spectra of nanowire quantum dots. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2021, 118, 161107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talantsev, E.; Iida, K.; Ohmura, T.; Matsumoto, T.; Crump, W.; Strickland, N.; Wimbush, S.; Ikuta, H. p-wave superconductivity in iron-based superconductors. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 14245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wang, W.S.; Zhang, C.C.; Zhang, F.C.; Wang, Q.H. Theory of chiral p-wave superconductivity with near nodes for Sr2RuO4. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2019, 122, 027002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yuan, N.F.; Mak, K.F.; Law, K. Possible topological superconducting phases of MoS2. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2014, 113, 097001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Frigeri, P.; Agterberg, D.; Koga, A.; Sigrist, M. Superconductivity without Inversion Symmetry: MnSi versus CePt3Si. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2004, 92, 097001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hardy, F.; Huxley, A. p-wave superconductivity in the ferromagnetic superconductor URhGe. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2005, 94, 247006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishida, K.; Mukuda, H.; Kitaoka, Y.; Asayama, K.; Mao, Z.; Mori, Y.; Maeno, Y. Spin-triplet superconductivity in Sr2RuO4 identified by 17O Knight shift. Nature 1998, 396, 658–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahan, G. Many-Particle Physics; Physics of Solids and Liquids; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wojs, A.; Hawrylak, P. Negatively charged magnetoexcitons in quantum dots. Phys. Rev. B 1995, 51, 10880–10885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hawrylak, P. Excitonic effects in optical spectra of a quasi-one-dimensional electron gas. Solid State Commun. 1992, 81, 525–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawrylak, P. Optical properties of a two-dimensional electron gas: Evolution of spectra from excitons to Fermi-edge singularities. Phys. Rev. B 1991, 44, 3821–3828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vora, P.M.; Bracker, A.S.; Carter, S.G.; Kim, M.; Kim, C.S.; Gammon, D. Strong coupling of a quantum dot molecule to a photonic crystal cavity. Phys. Rev. B 2019, 99, 165420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Adachi, S. Properties of Group-IV, III-V and II-VI Semiconductors; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2005; Chapter 6, p. 116; Chapter 7; pp. 150, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiße, A.; Fehske, H. Exact Diagonalization Techniques. In Computational Many-Particle Physics; Fehske, H., Schneider, R., Weiße, A., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2008; pp. 529–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalacu, D.; Poole, P.J.; Williams, R.L. Tailoring the geometry of bottom-up nanowires: Application to high efficiency single photon sources. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laferriere, P.; Yeung, E.; Giner, L.; Haffouz, S.; Lapointe, J.; Aers, G.C.; Poole, P.J.; Williams, R.L.; Dalacu, D. Multiplexed single-photon source based on multiple quantum dots embedded within a single nanowire. Nano Lett. 2020, 20, 3688–3693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laferriére, P.; Haffouz, S.; Northeast, D.B.; Poole, P.J.; Williams, R.L.; Dalacu, D. Position-controlled telecom single photon emitters operating at elevated temperatures. Nano Lett. 2023, 23, 962–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allami, H. Kitaev Exciton. 2023. Available online: https://github.com/hassan-allami/KitaevExciton.git (accessed on 26 July 2023).

| Index | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Configuration | ||||||||

| Label | ||||||||

| Parity | odd | even | odd | even | odd | even | odd | even |

| Excitation | ||||||||

| Energy | 0 | 0 |

| Even | Odd | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mohseni, M.; Allami, H.; Miravet, D.; Gayowsky, D.J.; Korkusinski, M.; Hawrylak, P. Majorana Excitons in a Kitaev Chain of Semiconductor Quantum Dots in a Nanowire. Nanomaterials 2023, 13, 2293. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano13162293

Mohseni M, Allami H, Miravet D, Gayowsky DJ, Korkusinski M, Hawrylak P. Majorana Excitons in a Kitaev Chain of Semiconductor Quantum Dots in a Nanowire. Nanomaterials. 2023; 13(16):2293. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano13162293

Chicago/Turabian StyleMohseni, Mahan, Hassan Allami, Daniel Miravet, David J. Gayowsky, Marek Korkusinski, and Pawel Hawrylak. 2023. "Majorana Excitons in a Kitaev Chain of Semiconductor Quantum Dots in a Nanowire" Nanomaterials 13, no. 16: 2293. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano13162293