Electrochemical Determination of Uric Acid Using a Nanocomposite Electrode with Molybdenum Disulfide/Multiwalled Carbon Nanotubes (MoS2@MWCNT)

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Reagents and Instruments

2.2. Measurements

2.3. Sample Treatment

2.4. Preparation of MWCNTs and MoS2@MWCNT/E

3. Results and Discussion

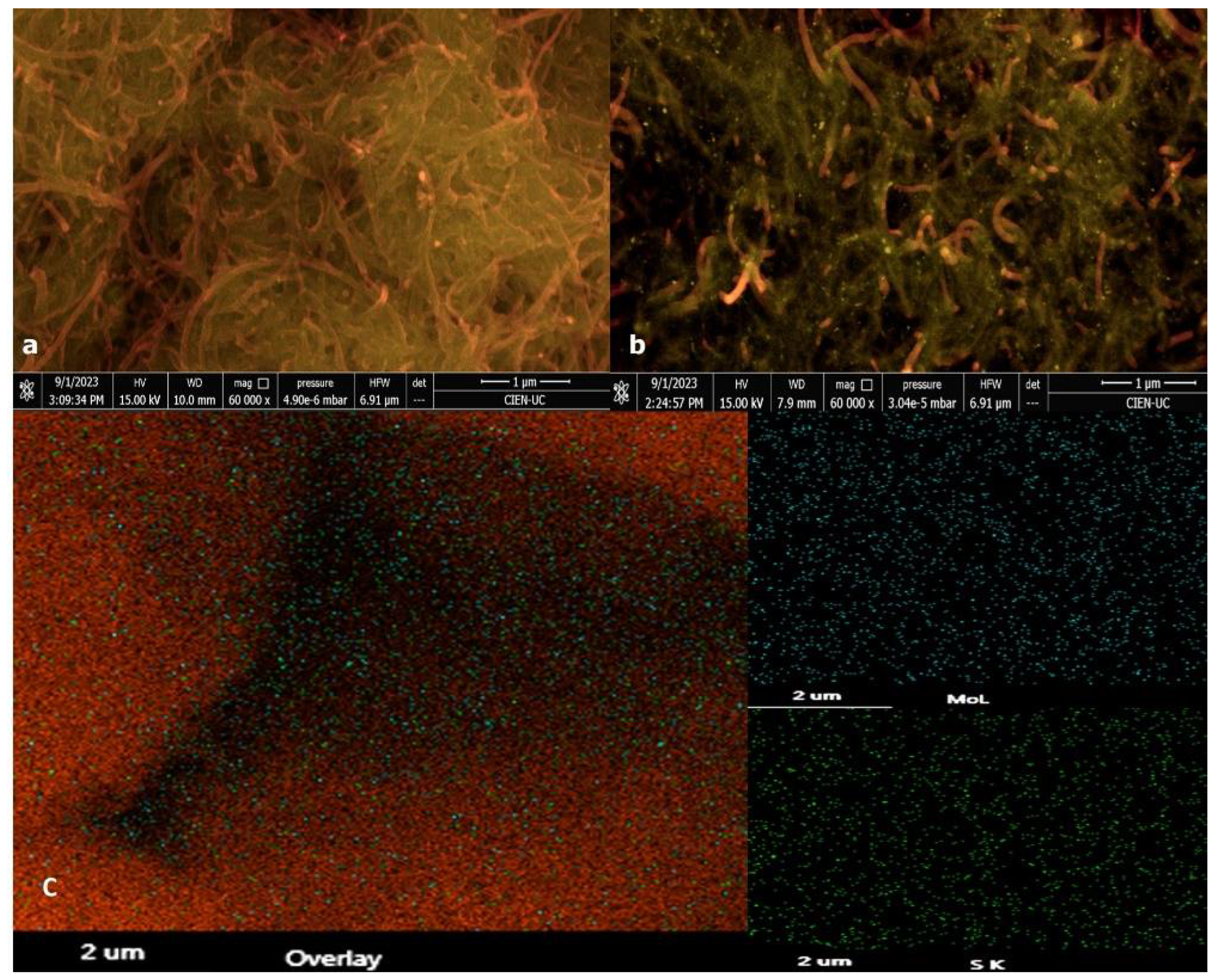

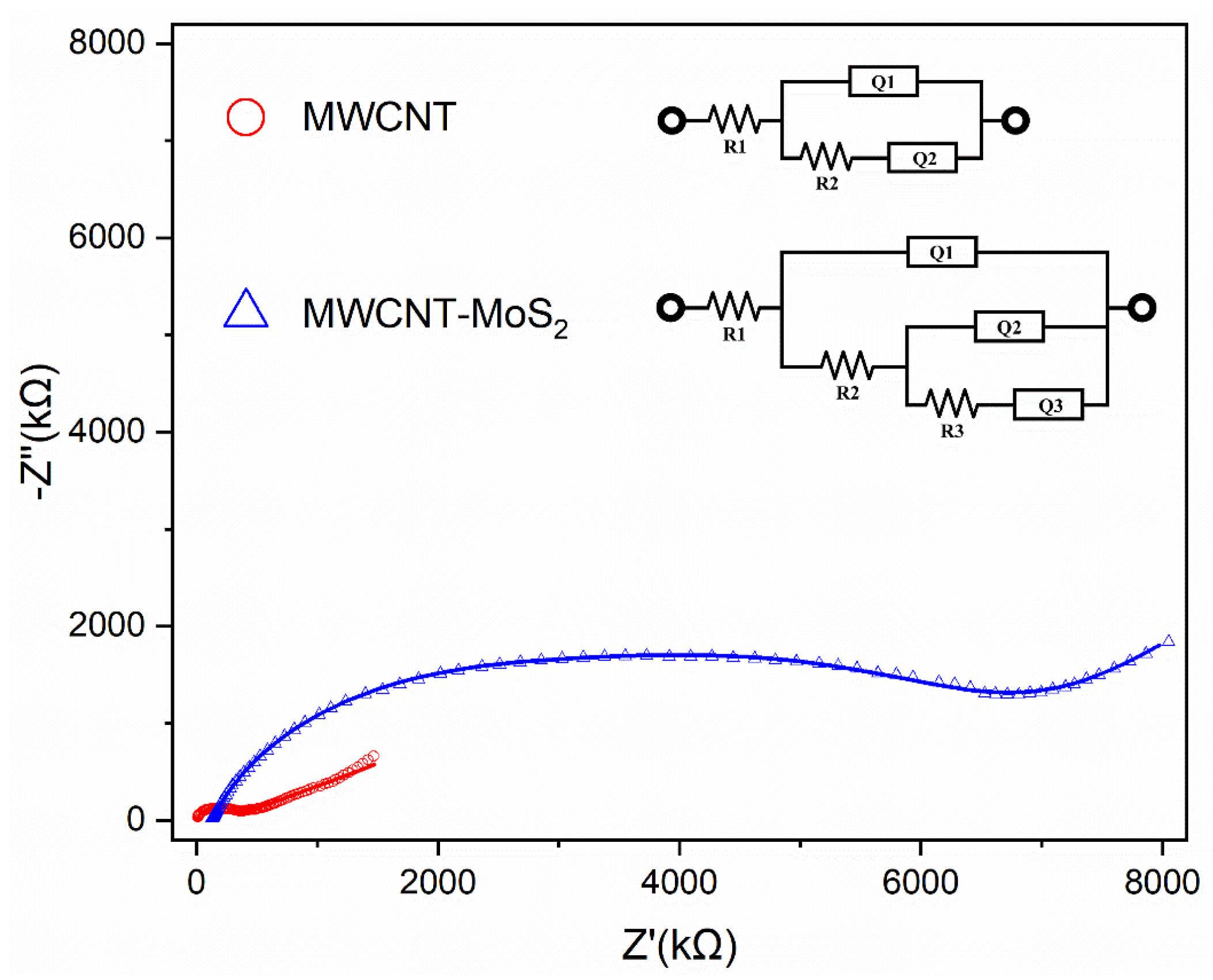

3.1. Surface Electrode Characterization

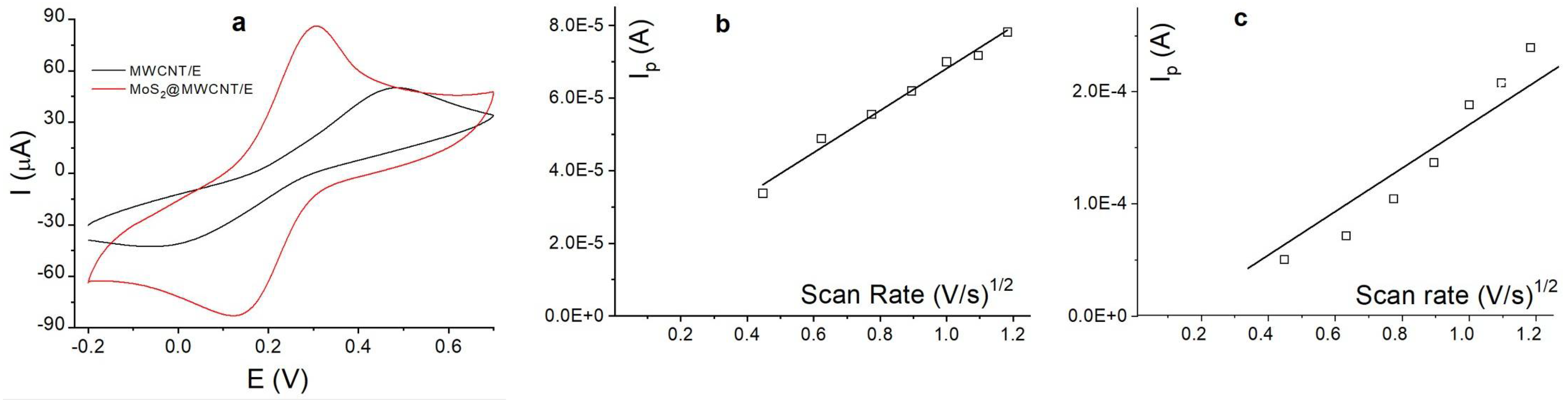

3.2. Electrochemical Characterization

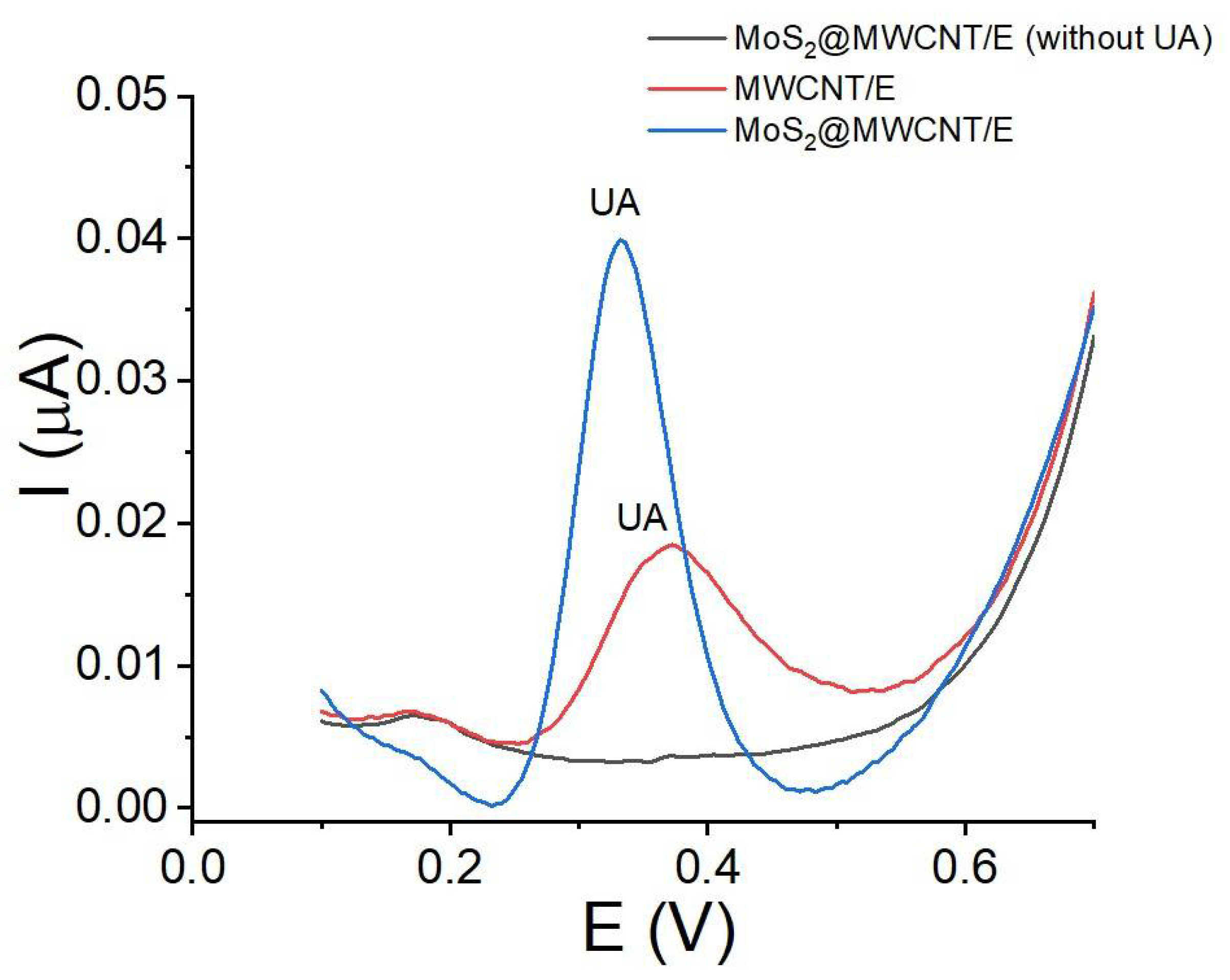

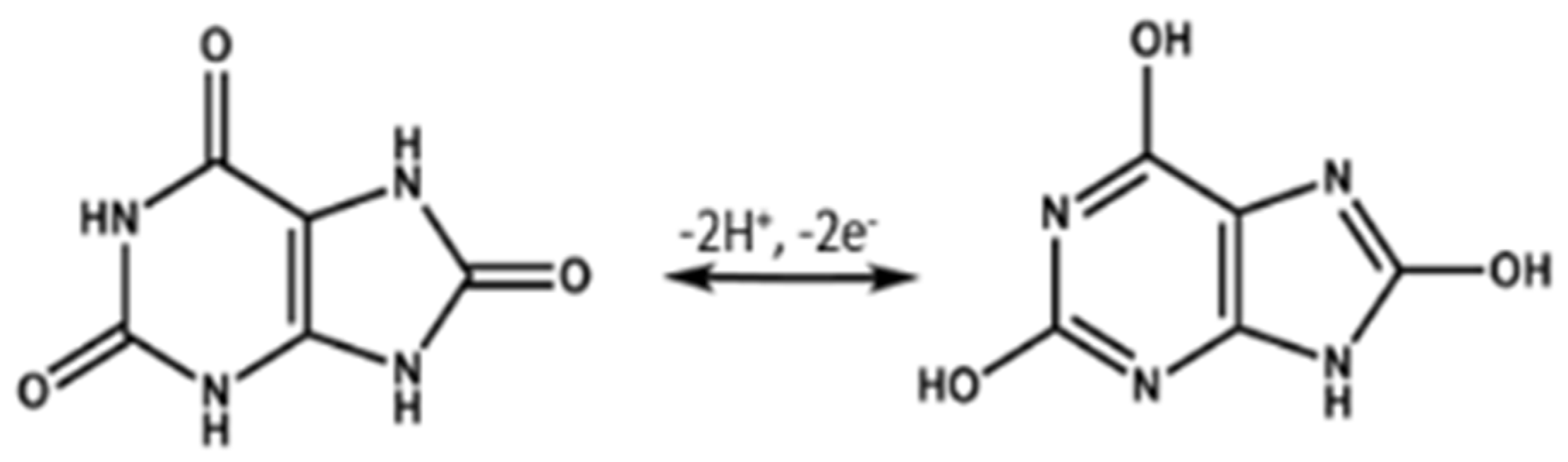

3.3. Electrochemical Activity of UA with MoS2@MWCNT/E

3.4. pH Effect

3.5. Parameter Optimization

3.6. Scan Rate Effect on UA Using MoS2@MWCNT/E

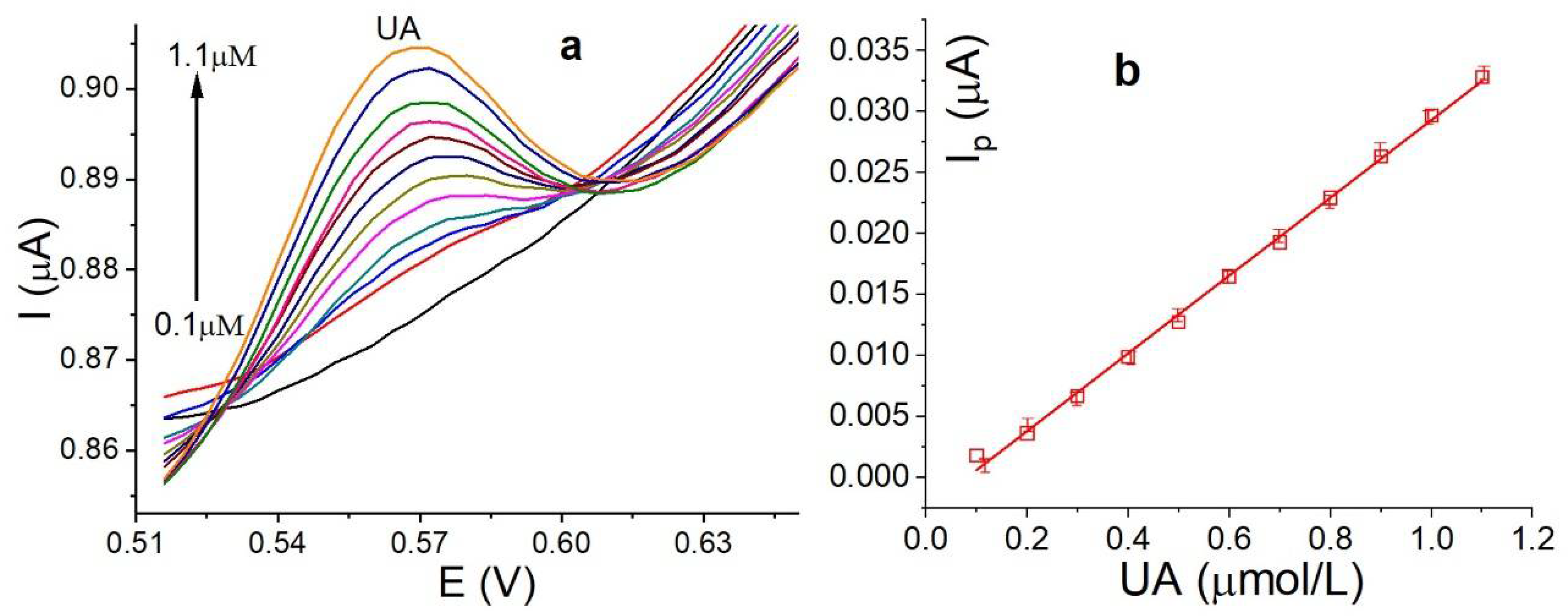

3.7. Calibration Curve, Detection Limits and Reproducibility

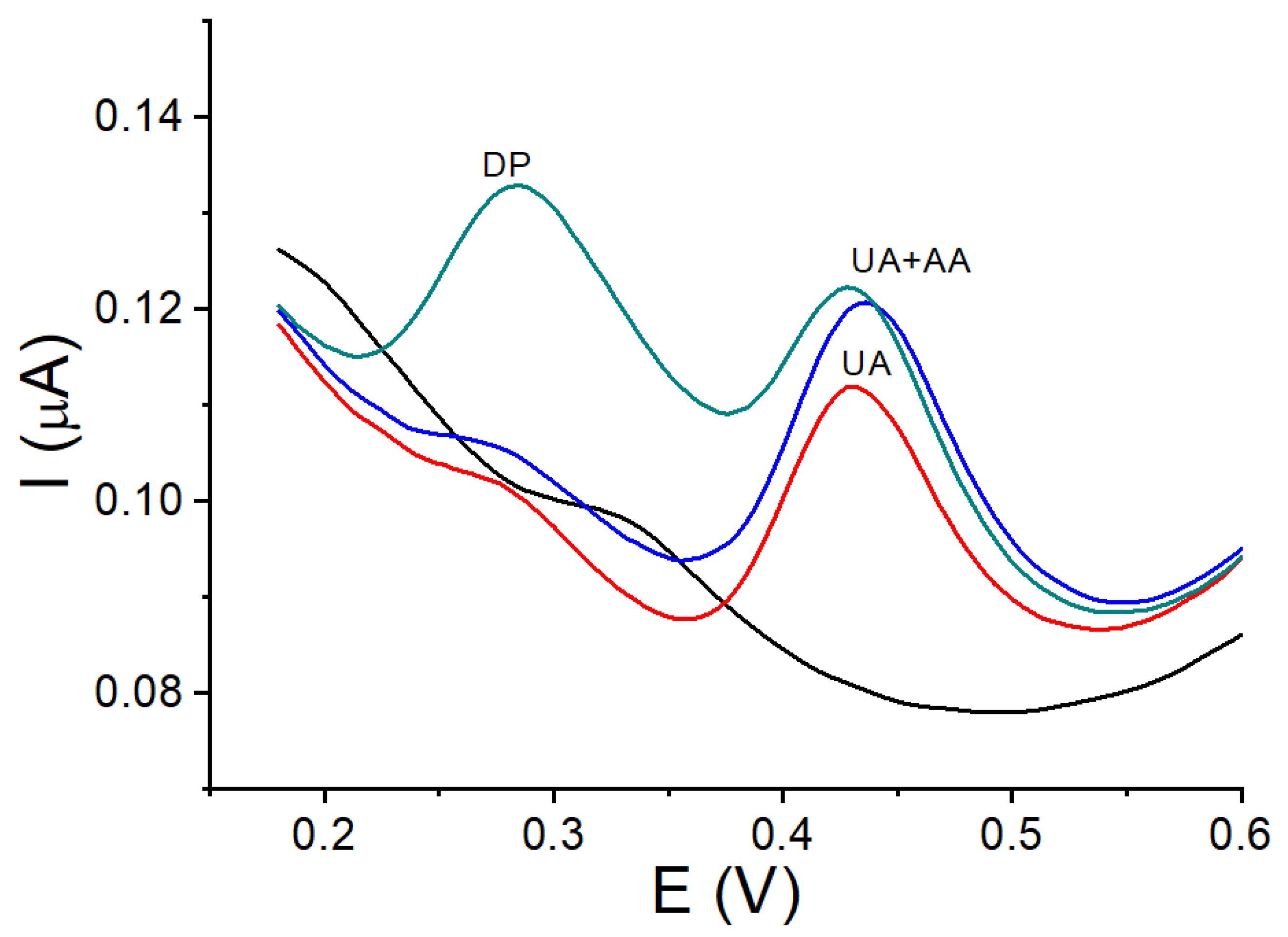

3.8. Interference Study with DP and AA

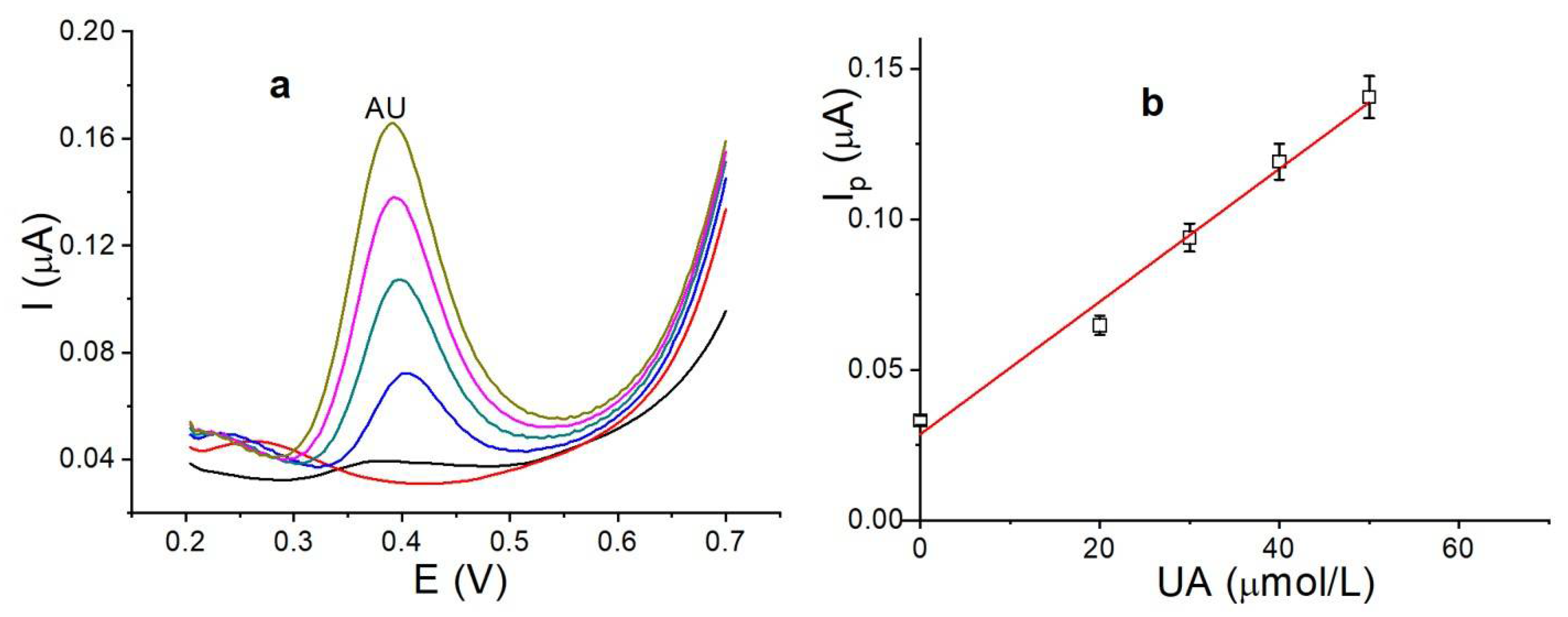

3.9. Analytical Application

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Desideri, G.; Castaldo, G.; Lombardi, A.; Mussap, M.; Testa, A.; POntremoli, R.; Punzi, L.; Borghi, C. Is it time to revise the normal range of serum uric acid levels? Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2014, 18, 1295–1306. [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Ruiz, F.; Dalbeth, N.; Bardin, T. A Review of Uric Acid, Crystal Deposition Disease, and Gout. Adv. Ther. 2015, 32, 31–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El Ridi, R.; Tallima, H. Physiological functions and pathogenic potential of uric acid: A review. J. Adv. Res. 2017, 8, 487–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saito, Y.; Tanaka, A.; Node, K.; Kobayashi, Y. Uric acid and cardiovascular disease: A clinical review. J. Cardiol. 2021, 78, 51–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Q.; Wen, X.; Kong, J. Recent Progress on Uric Acid Detection: A Review. Crit. Rev. Anal. Chem. 2020, 50, 359–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lakshmi, D.; Whitcombe, M.J.; Davis, F.; Sharma, S.P.; Prasad, B. Electrochemical Detection of Uric Acid in Mixed and Clinical Samples: A Review. Electroanalysis 2011, 23, 305–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aafria, S.; Kumari, P.; Sharma, S.; Yadav, S.; Batra, B.; Rana, J.S.; Sharma, M. Electrochemical biosensing of uric acid: A review. Microchem. J. 2022, 182, 107945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sha, R.; Vishnu, N.; Badhulika, S. MoS2 based ultra-low-cost, flexible, nonenzymatic and non-invasive electrochemical sensor for highly selective detection of Uric acid in human urine samples. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2019, 279, 53–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Yue, H.; Song, S.; Huang, S.; Gao, X.; Chen, H.; Wu, P.; Zhang, T.; Wang, Z. Simultaneous electrochemical determination of dopamine and uric acid based on MoS2 nanoflowers-graphene/ITO electrode. Microchem. J. 2020, 154, 104527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Lin, H.; Peng, H.; Qi, R.; Luo, C. A glassy carbon electrode modified with MoS2 nanosheets and poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene) for simultaneous electrochemical detection of ascorbic acid, dopamine and uric acid. Mikrochim. Acta 2016, 183, 2517–2523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, L.; Ma, Z. A glassy carbon electrode modified with a nanocomposite consisting of MoS2 and reduced graphene oxide for electrochemical simultaneous determination of ascorbic acid, dopamine, and uric acid. Mikrochim. Acta 2016, 183, 257–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Lu, J.; Zheng, X.; Chen, B.; Luo, Y.; Tahir, N.M.; Huang, B.; Xia, X.; Pan, X. A critical review on the applications and potential risks of emerging MoS2 nanomaterials. J. Hazard Mater. 2020, 399, 123057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Y.-F.; Sun, J.-H.; Wang, J.; Pi, Z.-X.; Wang, L.-C.; Yang, M.; Huang, X.-J. Sensitive and anti-interference stripping voltammetry analysis of Pb (II) in water using flower-like MoS2/rGO composite with ultra-thin nanosheets. Anal. Chim. Acta 2019, 1063, 64–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gan, X.; Zhao, H.; Quan, X. Two-dimensional MoS2: A promising building block for biosensors. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2017, 89, 56–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kukkar, M.; Sharma, A.; Kumar, P.; Kim, K.-H.; Deep, A. Application of MoS2 modified screen-printed electrodes for highly sensitive detection of bovine serum albumin. Anal. Chim. Acta 2016, 939, 101–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Mei, S.; Liu, S.; Hun, X. A photoelectrochemical sensing strategy based on single-layer MoS2 modified electrode for methionine detection. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2019, 165, 94–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramya, M.; Kumar, P.-S.; Rangasamy, G.; Shankar, V.-U.; Rajesh, G.; Nirmala, K. Experimental investigation of the electrochemical detection of sulfamethoxazole using copper oxide-MoS2 modified glassy carbon electrodes. Environ. Res. 2023, 216, 114463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, X.; Li, D.; Wei, O. A laccase based biosensor on AuNPs-MoS2 modified glassy carbon electrode for catechol detection. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2020, 186, 110683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, C.; Wang, C.; Sun, H.; Dai, D.; Gao, H. A simple electrochemical sensor based on rGO/MoS 2/CS modified GCE for highly sensitive detection of Pb (ii) in tobacco leaves. RSC Adv. 2021, 11, 29590–29597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, J.-J.; Zhu, J.-C.; Zhao, M.; Wang, Y.; Yang, P.; He, J. Ultrasensitive photoelectrochemical aptasensor for lead ion detection based on sensitization effect of CdTe QDs on MoS2-CdS:Mn nanocomposites by the formation of G-quadruplex structure. Talanta 2018, 183, 237–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, H.; Hu, Y.; Xie, B.; Zhu, J. High Sensitivity Electrochemical As (III) Sensor Based on Fe3O4/MoS2 Nanocomposites. Nanomaterials 2023, 13, 2288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aswathi, R.; Sandhya, K.-Y. Ultrasensitive and selective electrochemical sensing of Hg(ii) ions in normal and sea water using solvent exfoliated MoS2: Affinity matters. J. Mater. Chem. A 2018, 6, 14602–14613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santa Ana, M.; Benavente, A.E.; Gómez-Romero, P.; González, G. Poly(acrylonitrile)–molybdenum disulfide polymer electrolyte nanocomposite. J. Mater. Chem. 2006, 16, 3107–3113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, C.-H.; Cervini, R.; Clarke, S.-R.; Markovic, M.-G.; Matisons, J.-G.; Hawkins, S.-C.; Huynh, C.-P.; Simon, G.-P. The effect of functionalization on structure and electrical conductivity of multi-walled carbon nanotubes. J. Nanoparticle Res. 2008, 10, 77–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vijayaraj, K.; Dinakaran, T.; Lee, Y.; Kim, S.; Kim, H.; Lee, J.; Chang, S.-C. One-step construction of a molybdenum disulfide/multi-walled carbon nanotubes/polypyrrole nanocomposite biosensor for the ex-vivo detection of dopamine in mouse brain tissue. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2017, 494, 181–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagles, E.; Cardenas-Riojas, A.A.; Anaya-Roa, F.; Roldán-Tello, L. Amperometric Method for Detecting Paracetamol using a Carbon Paste Electrode Modified with Vanadium (V) Oxide. ChemistrySelect 2024, 9, e202304770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panneer, S.-S.; Hansa, M.; Yun, K. Simultaneous differential pulse voltammetric detection of uric acid and melatonin based on a self-assembled Au nanoparticle–MoS2 nanoflake sensing platform. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2020, 307, 127683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teferaa, M.; Tessemab, M.; Admassieb, S.; Wubeta, W. Voltammetric determination of uric acid using multiwall carbon nanotubes coated-poly(4-amino-3-hydroxy naphthalene sulfonic acid) modified glassy carbon electrode. Heliyon 2021, 7, 07575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finlayson, B.; Smith, A. Stability of first dissociable proton of uric acid. J. Chem. Eng. Data 1974, 19, 94–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamayo, L.-V.; Torres, J.-F.; Llanos-Penagos, J.; Calderón, J.-A.; Nagles, E.; García-Beltrán, O.; Hurtado, J.-J. Sensitive and profitable electrochemical detection of uric acid in the presence of dopamine with a novel carbon paste electrode decorated with a copper (II) complex. Electroanalysis 2019, 31, 2429–2436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Electrode | Slope (Ip/ν½) | Area (cm2) | Total Area (cm2) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ipa | Ipc | Ipa | Ipc | ||

| MWCNT/E | 5.8 × 10−5 | 1.4 × 10−5 | 0.015 | 0.004 | 0.019 |

| MoS2@MWCNT/E | 2.7 × 10−4 | 2.8 × 10−5 | 0.075 | 0.072 | 0.079 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Penagos-Llanos, J.; Segura, R.; de la Vega, A.P.; Pichun, B.; Liendo, F.; Riesco, F.; Nagles, E. Electrochemical Determination of Uric Acid Using a Nanocomposite Electrode with Molybdenum Disulfide/Multiwalled Carbon Nanotubes (MoS2@MWCNT). Nanomaterials 2024, 14, 958. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano14110958

Penagos-Llanos J, Segura R, de la Vega AP, Pichun B, Liendo F, Riesco F, Nagles E. Electrochemical Determination of Uric Acid Using a Nanocomposite Electrode with Molybdenum Disulfide/Multiwalled Carbon Nanotubes (MoS2@MWCNT). Nanomaterials. 2024; 14(11):958. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano14110958

Chicago/Turabian StylePenagos-Llanos, Johisner, Rodrigo Segura, Amaya Paz de la Vega, Bryan Pichun, Fabiana Liendo, Fernando Riesco, and Edgar Nagles. 2024. "Electrochemical Determination of Uric Acid Using a Nanocomposite Electrode with Molybdenum Disulfide/Multiwalled Carbon Nanotubes (MoS2@MWCNT)" Nanomaterials 14, no. 11: 958. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano14110958