Synthesis, Structural Characterization, and Infrared Analysis of Double Perovskites Pr2NiMnO6, Gd2NiMnO6, and Er2NiMnO6 Functional Nano-Ceramics

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results and Discussion

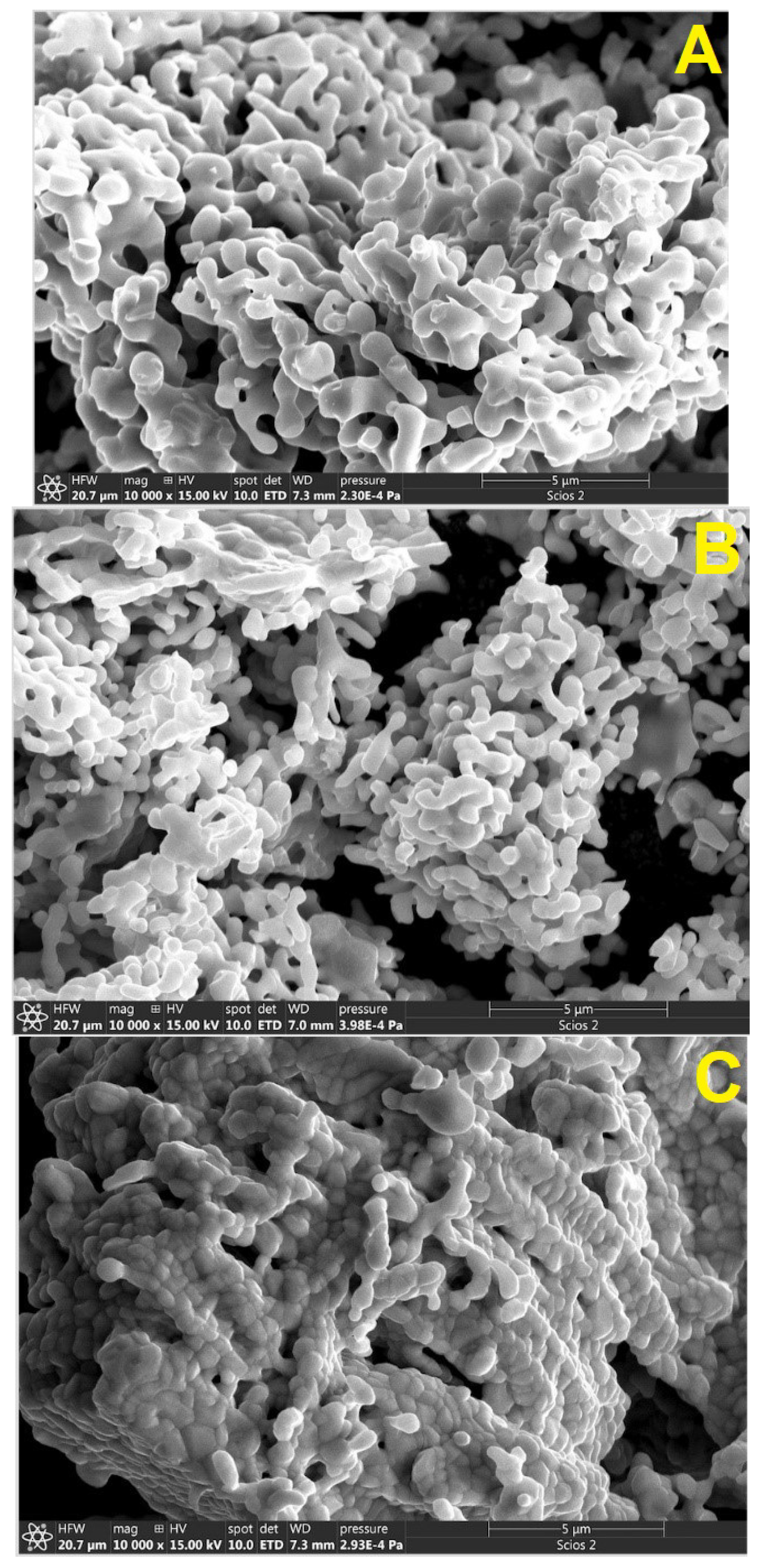

3.1. Morphology

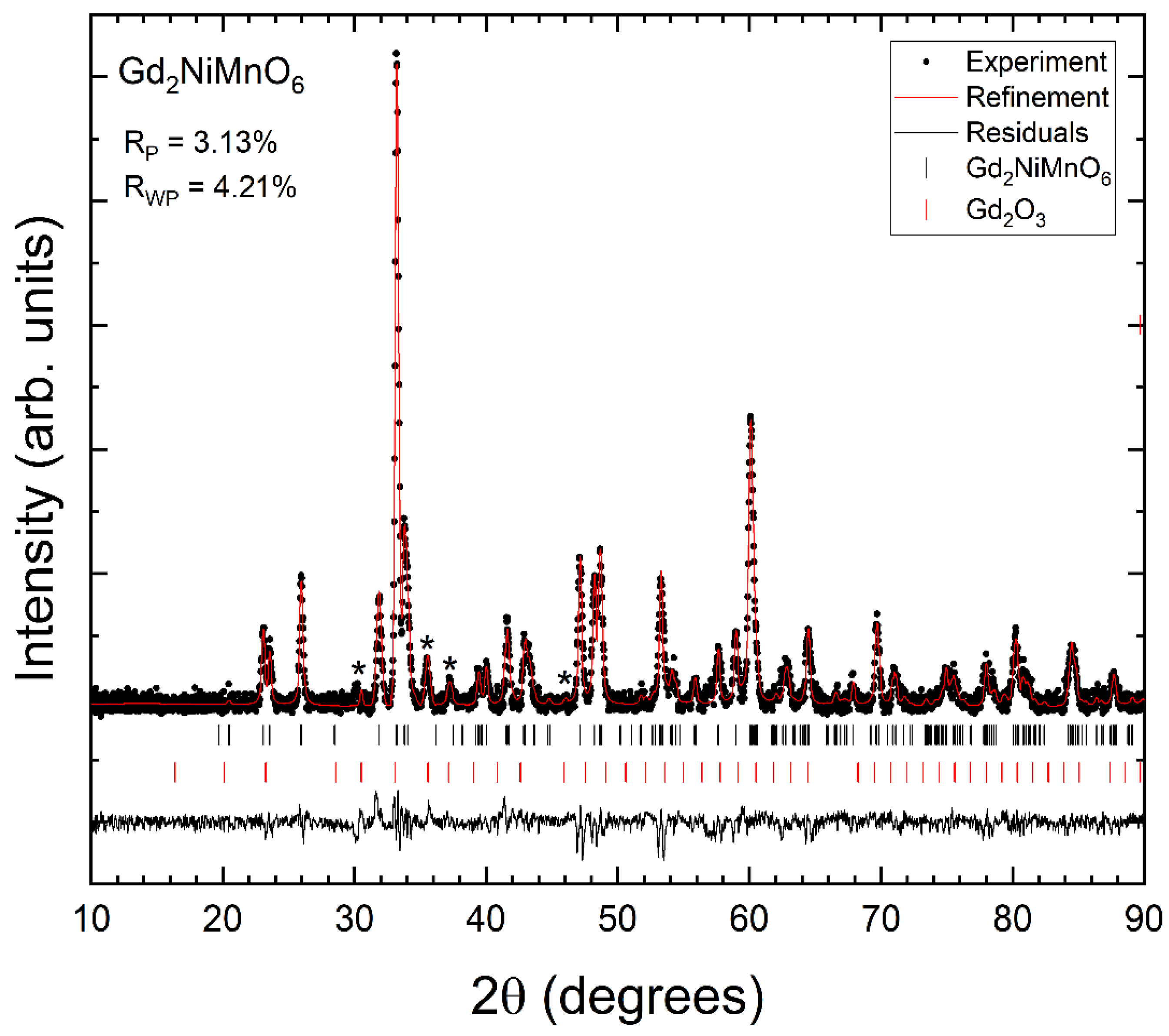

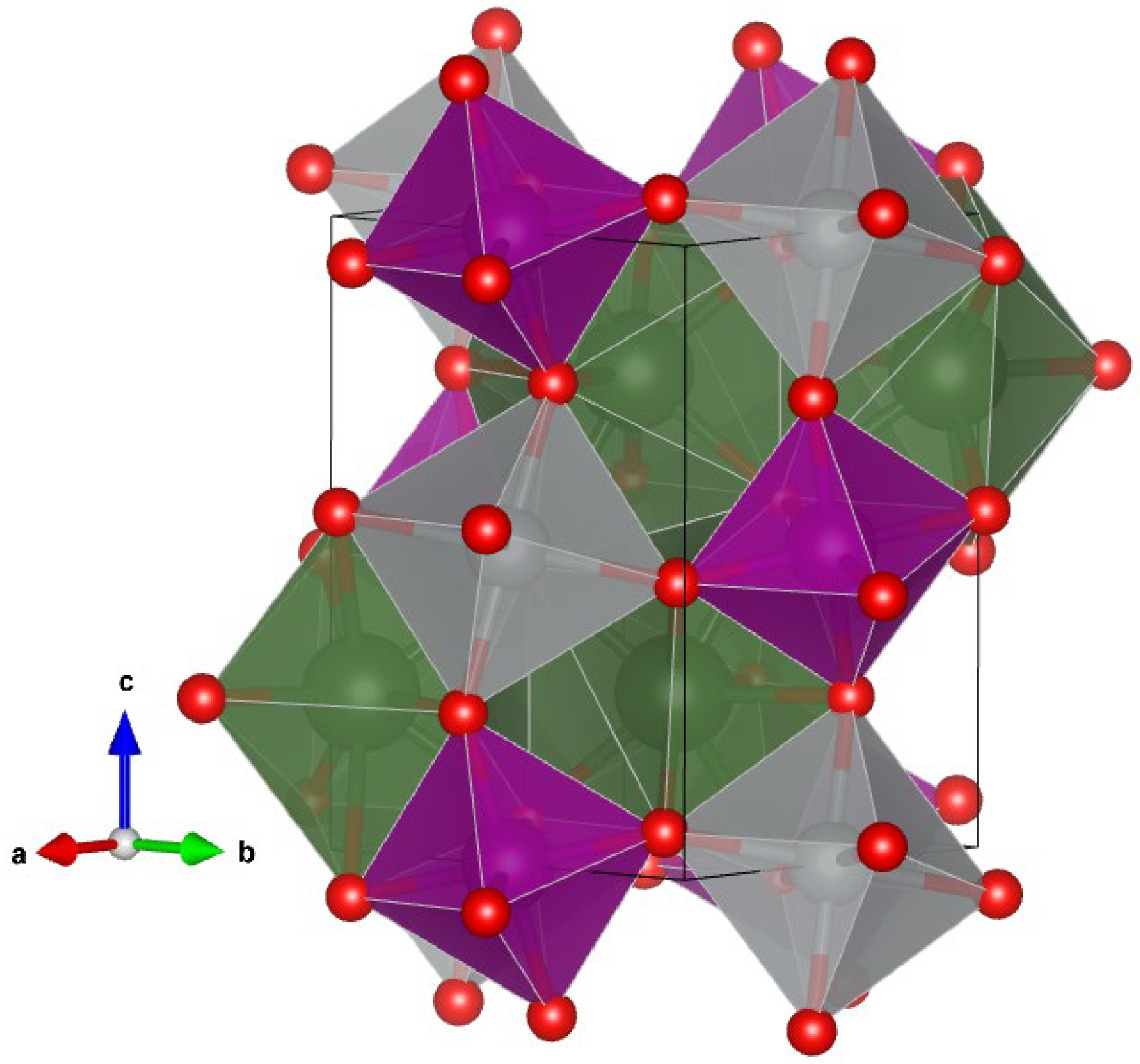

3.2. XRD Analysis

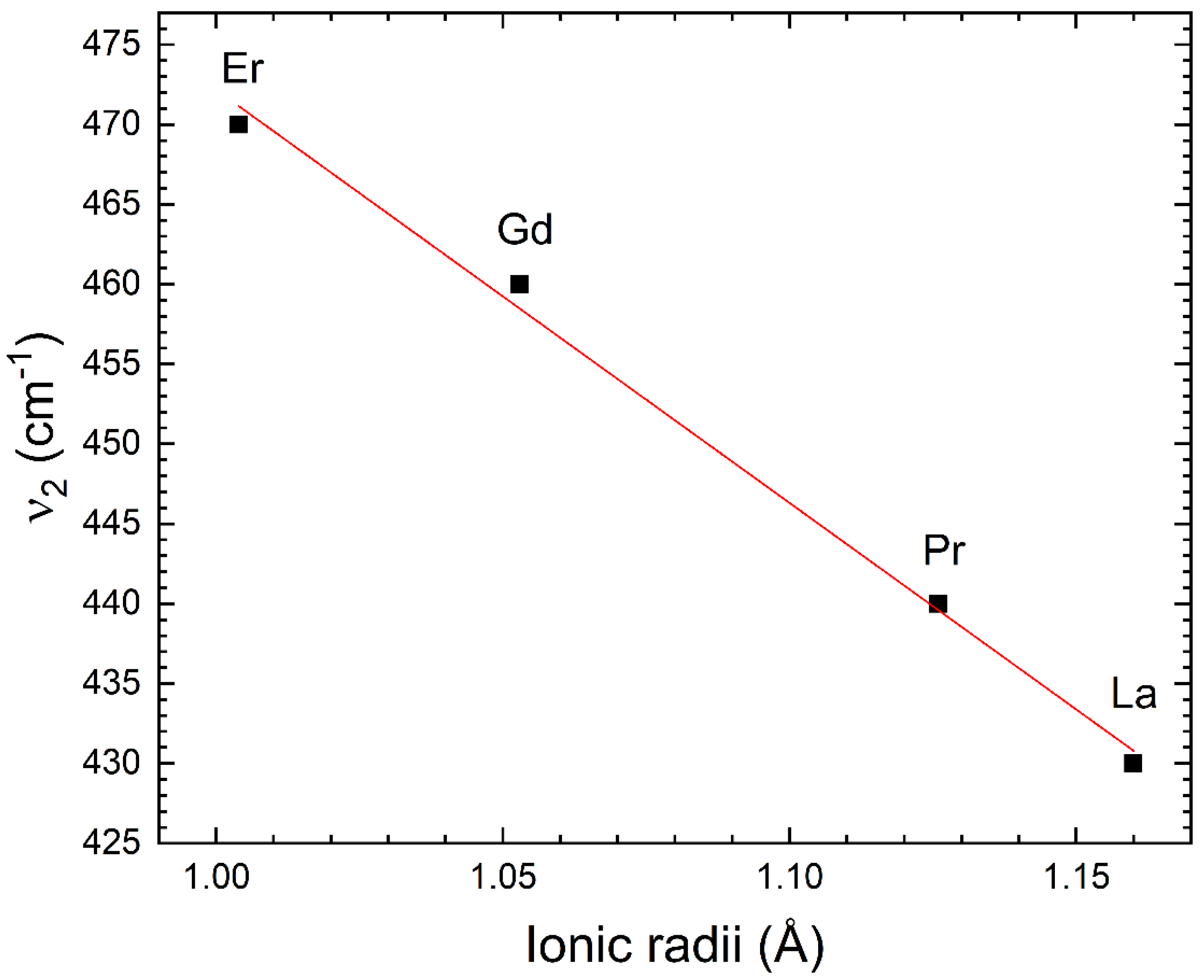

3.3. FTIR Measurements

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sun, H.; Chen, X.X.G.; Zhou, Y.; Lin, H.-J.; Chen, C.-T.; Ran, R.; Zhou, W.; Shao, Z. Smart Control of Composition for Double Perovskite Electrocatalysts toward Enhanced Oxygen Evolution Reaction. ChemSusChem 2019, 12, 5111–5116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, X.; Zhong, Y.; Shao, Z. Double Perovskites in Catalysis, Electrocatalysis, and Photo(electro)catalysis. Trends Chem. 2019, 1, 410–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oleś, M.; Horsch, P.; Feiner, L.F.; Khaliullin, G. Spin-Orbital Entanglement and Violation of the Goodenough-Kanamori Rules. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2006, 96, 147205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abass, S.; Bagri, A.; Sultan, K. Modifications induced in structural, electronic, and dielectric properties of Nd2NiMnO6 double perovskite by Sr doping. J. Alloys Compd. 2023, 930, 167463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Booth, R.J.; Fillman, R.; Whitaker, H.; Nag, A.; Tiwari, R.M.; Ramanujachary, K.V.; Gopalakrishnan, J.; Lofland, S.E. An investigation of structural, magnetic, and dielectric properties of R2NiMnO6 (R = rare earth, Y). Mater. Res. Bull. 2009, 44, 1559–1564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Y.; Cheng, Y.; Wang, H.; Zhang, Z.; Li, L. Magnetocaloric properties and critical behavior in double perovskite RE2CrMnO6 (RE = La, Pr, and Nd) compounds. Ceram. Int. 2020, 46, 25043–25049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shinde, K.P.; Lee, E.J.; Manawan, M.; Lee, A.; Park, S.Y.; Jo, Y.; Ku, K.; Kim, J.M.; Park, J.S. Structural; magnetic, and magnetocaloric properties of R2NiMnO6 (R = Eu, Gd, Tb). Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 20206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, N.; Kaushik, S.D.; Rao, K.S.; Babu, P.D.; Deshpande, S.K.; Achary, S.N.; Errandonea, D. Temperature Dependent Crystal Structure of Nd2CuTiO6: An In Situ Low Temperature Powder Neutron Diffraction Study. Crystals 2023, 13, 503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bessimou, M.; Masrour, R. Study of Optical, Magnetic, and Magnetocaloric Properties of Double Perovskites Dy2NiMnO6: First Principles Approach and Monte Carlo Simulations. J. Inorg. Organomet. Polym. Mater. 2024, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eerenstein, W.; Mathur, N.D.; Scott, J.F. Multiferroic and magnetoelectric materials. Nature 2006, 442, 759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, M.P.; Truong, K.D.; Jandl, S.; Fournier, P. Magnetic properties and phonon behavior of Pr2NiMnO6 thin films. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2011, 98, 162506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashisaka, M.; Kan, D.; Masuno, A.; Takano, M.; Shimakawa, Y.; Terashima, T.; Mibu, K. Epitaxial growth of ferromagnetic La2NiMnO6 with ordered double-perovskite structure. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2006, 89, 032504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogado, N.S.; Li, J.; Sleight, A.W.; Subramanian, M.A. Magnetocapacitance and magnetoresistance near room temperature in a ferromagnetic semiconductor: La2NiMnO6. Adv. Mater. 2005, 17, 2225–2227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Sun, L.P.; Feng, Q.; Huo, L.H.; Zhao, H.; Bassat, J.M.; Rougier, A.; Fourcade, S.; Grenier, J.C. Investigation of Pr2NiMnO6-Ce0.9Gd0.1O1.95 composite cathode for intermediate-temperature solid oxide fuel cells. J. Solid State Electrochem. 2017, 21, 273–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, D.; Zhou, J.; Huang, Y.C.; Dong, C.-L.; Wang, J.-Q.; Zhou, W.; Shao, Z. Screening highly active perovskites for hydrogen-evolving reaction via unifying ionic electronegativity descriptor. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 3755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maneesha, P.; Baral, S.C.; Rini, E.G.; Sen, S. An overview of the recent developments in the structural correlation of magnetic and electrical properties of Pr2NiMnO6 double perovskite. Prog. Solid. State Chem. 2023, 70, 100402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Retuerto, M.; Muñoz, A.; Martínez-Lope, M.J.; Alonso, J.A.; Mompeán, F.J.; Fernández-Díaz, M.T.; Sánchez-Benítez, J. Magnetic Interactions in the Double Perovskites R2NiMnO6 (R = Tb, Ho, Er, Tm) Investigated by Neutron Diffraction. Inorg. Chem. 2015, 54, 10890–10900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miguel, A.S. Nanomaterials under high-pressure. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2006, 35, 876–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anirban, S.; Dutta, A. Understanding the structure and charge transport mechanism of Sm2NiMnO6 double perovskite prepared via low temperature auto-ignition method. Phys. Lett. A 2021, 397, 127256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, W.; Liang, Q.; Matsushita, Y.; Tanaka, M.; Belik, A.A. High-Pressure Synthesis, Crystal Structure, and Properties of In2NiMnO6 with Antiferromagnetic Order and Field-Induced Phase Transition. Inorg. Chem. 2013, 52, 14108–14115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, D.; Yi, Y.; Song, Y.; Guan, D.; Xu, M.; Ran, R.; Wang, W.; Zhou, W.; Shao, Z. The BaCe0.16Y0.04Fe0.8O3−δ nanocomposite: A new high-performance cobalt-free triple-conducting cathode for protonic ceramic fuel cells operating at reduced temperatures. J. Mater. Chem. A 2022, 10, 5381–5390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saiki, A.; Ishizawa, N.; Mizutani, N.; Kato, M. Structural Change of C-Rare Earth Sesquioxides Yb2O3 and Er2O3 as a Function of Temperature. J. Ceram. Soc. Jpn. 1985, 93, 649–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudenko, V.S.; Boganov, A.G. Stoichiometry and phase transitions in rare earth oxides. Inorg. Mater. 1970, 6, 1893–1898. [Google Scholar]

- Rietveld, H.M. A profile refinement method for nuclear and magnetic structures. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 1969, 2, 65–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaduk, J.A. A Rietveld tutorial-Mullite. Powder Diffr. 2009, 24, 351–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scardi, P. Diffraction Line Profiles in the Rietveld Method. Cryst. Growth Des. 2020, 20, 6903–6916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohapatra, S.R.; Sahu, B.; Raut, S.; Kaushik, S.D.; Singh, A.K. Investigation on structural, optical and magnetic properties of double perovskite Gd2NiMnO6. AIP Conf. Proc. 2015, 1665, 140032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langford, J.I.; Wilson, A.J.C. Scherrer after sixty years: A survey and some new results in the determination of crystallite size. J. Appl. Cryst. 1978, 11, 102–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patterson, A. The Scherrer Formula for X-Ray Particle Size Determination. Phys. Rev. 1939, 56, 978–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Errandonea, D.; Garg, A.B. Recent progress on the characterization of the high-pressure behaviour of AVO4 orthovanadates. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2018, 97, 123–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Errandonea, D.; Manjon, F.J. Pressure effects on the structural and electronic properties of ABX4 scintillating crystals. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2008, 53, 711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ridley, C.J.; Daisenberger, D.; Wilson, C.W.; Stenning, G.B.G.; Sankar, G.; Knight, K.S.; Tucker, M.G.; Smith, R.I.; Bull, C.L. High-Pressure Study of the Elpasolite Perovskite La2NiMnO6. Inorg. Chem. 2019, 58, 9016–9027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Errandonea, D.; Santamaria-Perez, D.; Martinez-Garcia, D.; Gomis, O.; Shukla, R.; Achary, S.N.; Tyagi, A.K.; Popescu, C. Pressure Impact on the Stability and Distortion of the Crystal Structure of CeScO3. Inorg. Chem. 2017, 56, 8363–8371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garg, A.B.; Muñoz, A.; Anzellini, S.; Sánchez-Martín, J.; Turnbull, R.; Díaz-Anichtchenko, D.; Popescu, C.; Errandonea, D. Role of GdO addition in the structural stability of cubic Gd2O3 at high pressures: Determination of the equation of states of GdO and Gd2O3. Materialia 2024, 34, 102064. [Google Scholar]

- Elhamel, M.; Hebboul, Z.; Naidjate, M.E.; Draoui, A.; Benghia, A.; Fadla, M.A.; Kanoun, M.B.; Goumri-Said, S. Experimental synthesis of double perovskite functional nano-ceramic Eu2NiMnO6: Combining optical characterization and DFT calculations. J. Solid State Chem. 2023, 323, 124022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, J.; Siddique, M.; Khan, J.A.; Bukhari, S.H.; Sultan, T. Impact of rare earth substitution on structural and optical properties of multiferroic La2−xGdxNiMnO6. Mater. Res. Express 2019, 6, 126311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, R.; Sheikh, M.S.; Sinha, T.P. Sintering Temperature Dependent Optical and Vibrational Properties of Sm2NiMnO6 Nanoparticle. J. Nano-Electron. Phys. 2019, 11, 06010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, D.; Lampronti, G.I.; Haines, C.R.S.; Carpenter, M.A. Magnetoelastic coupling behavior at the ferromagnetic transition in the partially disordered double perovskite La2NiMnO6. Phys. Rev. B 2019, 100, 014304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truong, K.D.; Singh, M.P.; Jandl, S.; Fournier, P. Investigation of phonon behavior in Pr2NiMnO6 by micro-Raman spectroscopy. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 2011, 23, 052202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iliev, M.N.; Guo, H.; Gupta, A. Raman spectroscopy evidence of strong spin-phonon coupling in epitaxial thin films of the double perovskite La2NiMnO6. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2007, 90, 151914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Fuertes, J.; Errandonea, D.; López-Moreno, S.; González, J.; Gomis, O.; Vilaplana, R.; Manjón, F.J.; Muñoz, A.; Rodríguez-Hernández, P.; Friedrich, A.; et al. High-pressure Raman spectroscopy and lattice-dynamics calculations on scintillating MgWO4: Comparison with isomorphic compounds. Phys. Rev. B 2011, 83, 214112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasir, M.; Kumar, S.; Patra, N.; Bhattacharya, D.; Jha, S.N.; Basaula, D.R.; Bhatt, S.; Khan, M.; Liu, S.W.; Biring, S.; et al. Role of Antisite Disorder, Rare-Earth Size, and Superexchange Angle on Band Gap, Curie Temperature, and Magnetization of R2NiMnO6 Double Perovskites. ACS Appl. Electron. Mater. 2019, 1, 141–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bucknum, M.J. Chemical Physics of Phonons and Superconductivity: A Heuristic Approach. Nat. Preced. 2008, 1586, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Errandonea, D.; Boehler, R.; Ross, M. Melting of the Rare Earth Metals and f-Electron Delocalization. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2000, 85, 3444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, A.; Rahman, S.; Rodriguez-Hernandez, P.; Muñoz, A.; Manjón, F.J.; Nenert, G.; Errandonea, D. High-Pressure Raman Study of Fe(IO3)3: Soft-Mode Behavior Driven by Coordination Changes of Iodine Atoms. J. Phys. Chem. C 2020, 124, 21329–21337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Ni(NO3)2·6H2O | MnCl2·4H2O | Product | Particle Size (nm) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L | S | ||||

| Pr(NO3)3·6H2O 0.435 g | 0.182 g | 0.197 g | Pr2NiMnO6 98% Pr2O3 2% | 37(4) | 45(4) |

| Er2O3 0.382 g | Er2NiMnO6 94% Er2O3 6% | 40(4) | 49(5) | ||

| Gd(NO3)3·6H2O 0.451 g | Gd2NiMnO6 98% Gd2O3 4% | 29(3) | 36(3) | ||

| Pr2NiMnO6 | Gd2NiMnO6 | Er2NiMnO6 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| a (Å) | 5.4432(5) | 5.2978(5) | 5.2302(5) |

| b (Å) | 5.5095(5) | 5.6119(5) | 5.6392(5) |

| c (Å) | 7.7101(7) | 7.5406(7) | 7.4533(5) |

| β (°) | 90.17(3) | 90.21(3) | 90.21(3) |

| V (Å3) | 231.2(1) Å3 | 224.2(1) Å3 | 219.8(1) Å3 |

| K (GPa) | 173(5) | 176(5) | 179(5) |

| Pr2NiMnO6 | ||||

| site | x | y | z | |

| Pr | 4e | 0.9824(5) | 0.0705(5) | 0.2504(5) |

| Ni | 2d | 0.5 | 0 | 0 |

| Mn | 2c | 0.5 | 0 | 0.5 |

| O1 | 4e | 0.1074(12) | 0.4627(12) | 0.2423(12) |

| O2 | 4e | 0.7009(12) | 0.3123(12) | 0.0505(12) |

| O3 | 4e | 0.1783(12) | 0.2057(12) | 0.9446(12) |

| Gd2NiMnO6 | ||||

| site | x | y | z | |

| Gd | site | 0.9832(5) | 0.0713(5) | 0.2501(5) |

| Ni | 4e | 0.5 | 0 | 0 |

| Mn | 2d | 0.5 | 0 | 0.5 |

| O1 | 2c | 0.1082(12) | 0.4621(12) | 0.2435(12) |

| O2 | 4e | 0.7016(12) | 0.3118(12) | 0.0515(12) |

| O3 | 4e | 0.1771(12) | 0.2059(12) | 0.9441(12) |

| Er2NiMnO6 | ||||

| site | x | y | z | |

| Er | site | 0.9821(5) | 0.0701(5) | 0.2512(5) |

| Ni | 4e | 0.5 | 0 | 0 |

| Mn | 2d | 0.5 | 0 | 0.5 |

| O1 | 2c | 0.1077(12) | 0.4330(12) | 0.2428(12) |

| O2 | 4e | 0.7013(12) | 0.3133(12) | 0.0499(12) |

| O3 | 4e | 0.1788(12) | 0.2051(12) | 0.9448(12) |

| Lanthanide | Pr | Gd | Er |

|---|---|---|---|

| NiO6 octahedron | |||

| Ni-O1 (x2) | 2.083(10) Å | 2.031(9) Å | 2.030(9) Å |

| Ni-O2 (x2) | 2.075(7) Å | 2.086(7) Å | 2.091(7) Å |

| Ni-O3 (x2) | 2.128(7) Å | 2.106(7) Å | 2.079(7) Å |

| MnO6 octahedron | |||

| Mn-O1 (x2) | 1.967(10) Å | 1.933(9) Å | 1.936(9) Å |

| Mn-O2 (x2) | 1.969(7) Å | 1.942(7) Å | 1.924(7) Å |

| Mn-O3 (x2) | 1.938(7) Å | 1.945(7) Å | 1.952(7) Å |

| Ni-O-Mn angles | |||

| Ni-O1-Mn | 144.3(3) | 144.5(3) | 144.6(3) |

| Ni-O2-Mn | 146.5(3) | 146.4(3) | 146.6(3) |

| Ni-O3-Mn | 144.3(3) | 144.2(3) | 144.1(3) |

| RO8 polyhedron | |||

| R-O1 | 2.266(8) Å | 2.251(7) Å | 2.150(8) Å |

| R-O1 | 2.311(8) Å | 2.292(8) Å | 2.281(7) Å |

| R-O2 | 2.320(6) Å | 2.308(6) Å | 2.283(6) Å |

| R-O2 | 2.546(7) Å | 2.504(7) Å | 2.493(7) Å |

| R-O2 | 2.677(5) Å | 2.630(5) Å | 2.603(5) Å |

| R-O3 | 2.309(6) Å | 2.297(7) Å | 2.284(7) Å |

| R-O3 | 2.553(7) Å | 2.520(7) Å | 2.499(7) Å |

| R-O3 | 2.696(5) Å | 2.640(5) Å | 2.614(5) Å |

| Compound | Z | Ionic Radii (Å) | ν1 (cm−1) | ν2 (cm−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| La2NiMnO6 | 57 | 1.160 | 600 | 430 |

| Pr2NiMnO6 | 59 | 1.126 | 590 | 440 |

| Sm2NiMnO6 | 62 | 1.079 | 575 | |

| Eu2NiMnO6 | 63 | 1.066 | 602 | |

| Gd2NiMnO6 | 64 | 1.053 | 595 | 460 |

| Er2NiMnO6 | 68 | 1.004 | 602 | 470 |

| Element | Shannon Ionic Radii. Coord. 8 * | Frequency (cm−1) |

|---|---|---|

| La | 1.160 | 431(19) |

| Ce | 1.143 | 435(19) |

| Pr | 1.126 | 439(19) |

| Nd | 1.109 | 444(19) |

| Pm | 1.093 | 448(19) |

| Sm | 1.079 | 452(19) |

| Eu | 1.066 | 455(18) |

| Gd | 1.053 | 458(18) |

| Tb | 1.040 | 462(18) |

| Dy | 1.027 | 465(18) |

| Ho | 1.015 | 468(18) |

| Er | 1.004 | 471(18) |

| Tm | 0.994 | 474(18) |

| Yb | 0.985 | 476(18) |

| Lu | 0.977 | 478(18) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Elhamel, M.; Hebboul, Z.; Benbertal, D.; Botella, P.; Errandonea, D. Synthesis, Structural Characterization, and Infrared Analysis of Double Perovskites Pr2NiMnO6, Gd2NiMnO6, and Er2NiMnO6 Functional Nano-Ceramics. Nanomaterials 2024, 14, 960. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano14110960

Elhamel M, Hebboul Z, Benbertal D, Botella P, Errandonea D. Synthesis, Structural Characterization, and Infrared Analysis of Double Perovskites Pr2NiMnO6, Gd2NiMnO6, and Er2NiMnO6 Functional Nano-Ceramics. Nanomaterials. 2024; 14(11):960. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano14110960

Chicago/Turabian StyleElhamel, Mebark, Zoulikha Hebboul, Djamal Benbertal, Pablo Botella, and Daniel Errandonea. 2024. "Synthesis, Structural Characterization, and Infrared Analysis of Double Perovskites Pr2NiMnO6, Gd2NiMnO6, and Er2NiMnO6 Functional Nano-Ceramics" Nanomaterials 14, no. 11: 960. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano14110960

APA StyleElhamel, M., Hebboul, Z., Benbertal, D., Botella, P., & Errandonea, D. (2024). Synthesis, Structural Characterization, and Infrared Analysis of Double Perovskites Pr2NiMnO6, Gd2NiMnO6, and Er2NiMnO6 Functional Nano-Ceramics. Nanomaterials, 14(11), 960. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano14110960