Harnessing Magnetic Nanoparticles for the Effective Removal of Micro- and Nanoplastics: A Critical Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

Sources of Plastic in the Environment

2. Properties of MPs and NPs

- A wide size range, ranging from 1 μm to 1 mm (and up to 5 mm for larger MPs).

- Diverse polymer types with varying chemical compositions, including both conventional and biopolymers with different structures and densities.

- Various shapes such as spheres, irregular particles, fibers, films, and foams.

- The incorporation of different additives (antioxidants, light stabilizers, plasticizers, flame retardants, pigments, etc.), weathering byproducts, and adsorbed contaminants (persistent organic pollutants, antibiotics, heavy metals, etc.).

- Different aging states (primary and secondary MPs), biofouling, surface charge, and hydrophobicity [2].

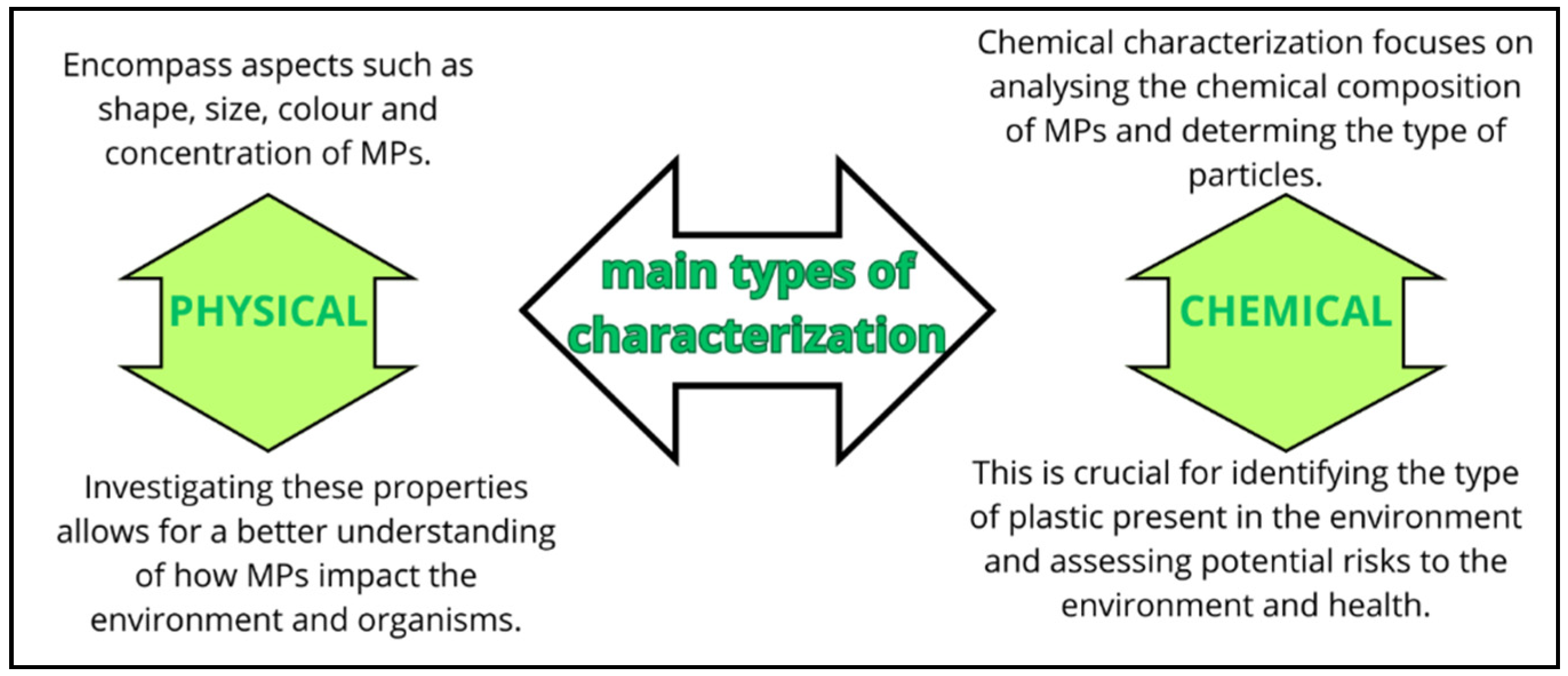

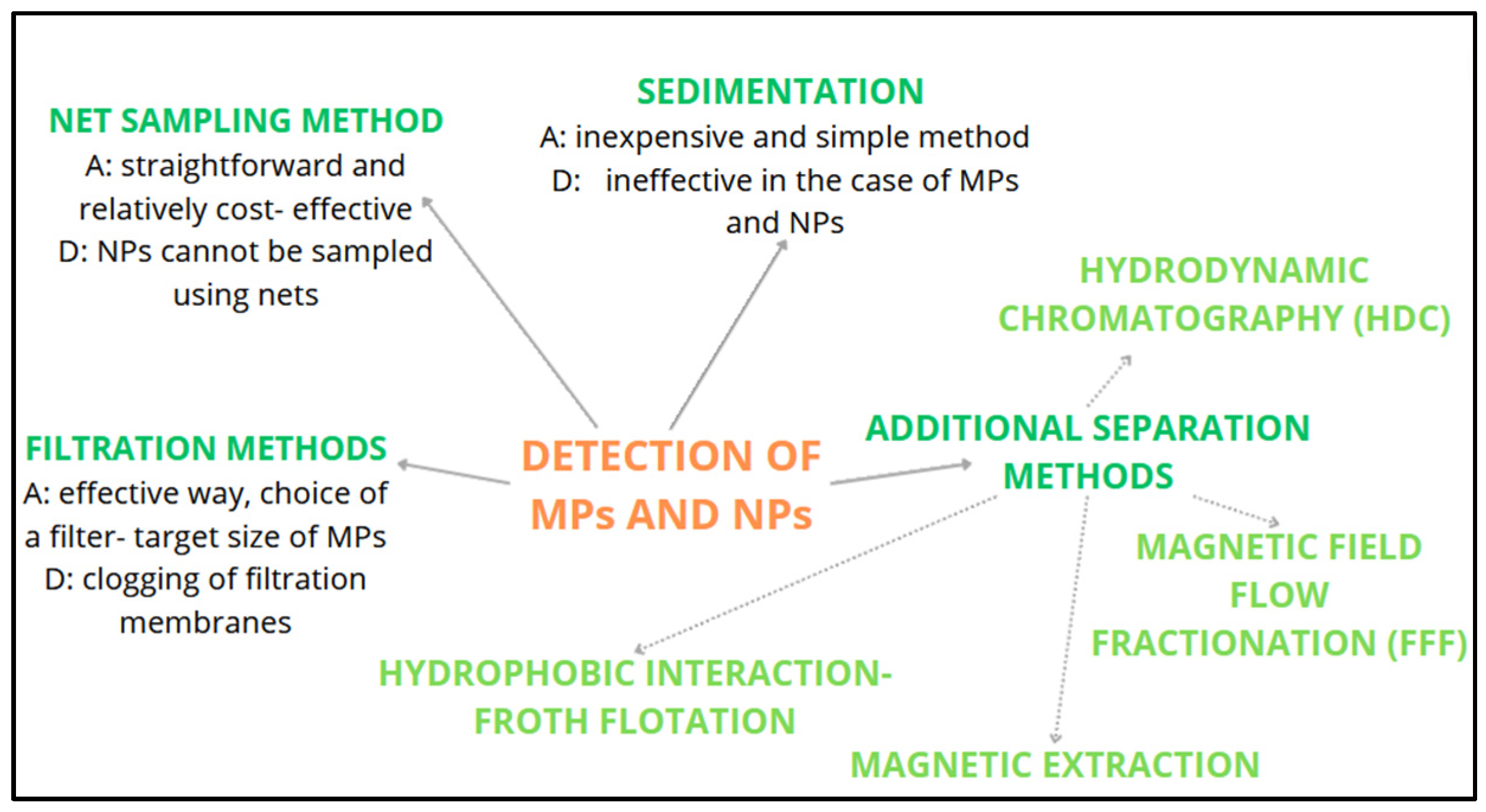

3. Detection of MPs and NPs

4. Impact on the Environment and Human Healthy

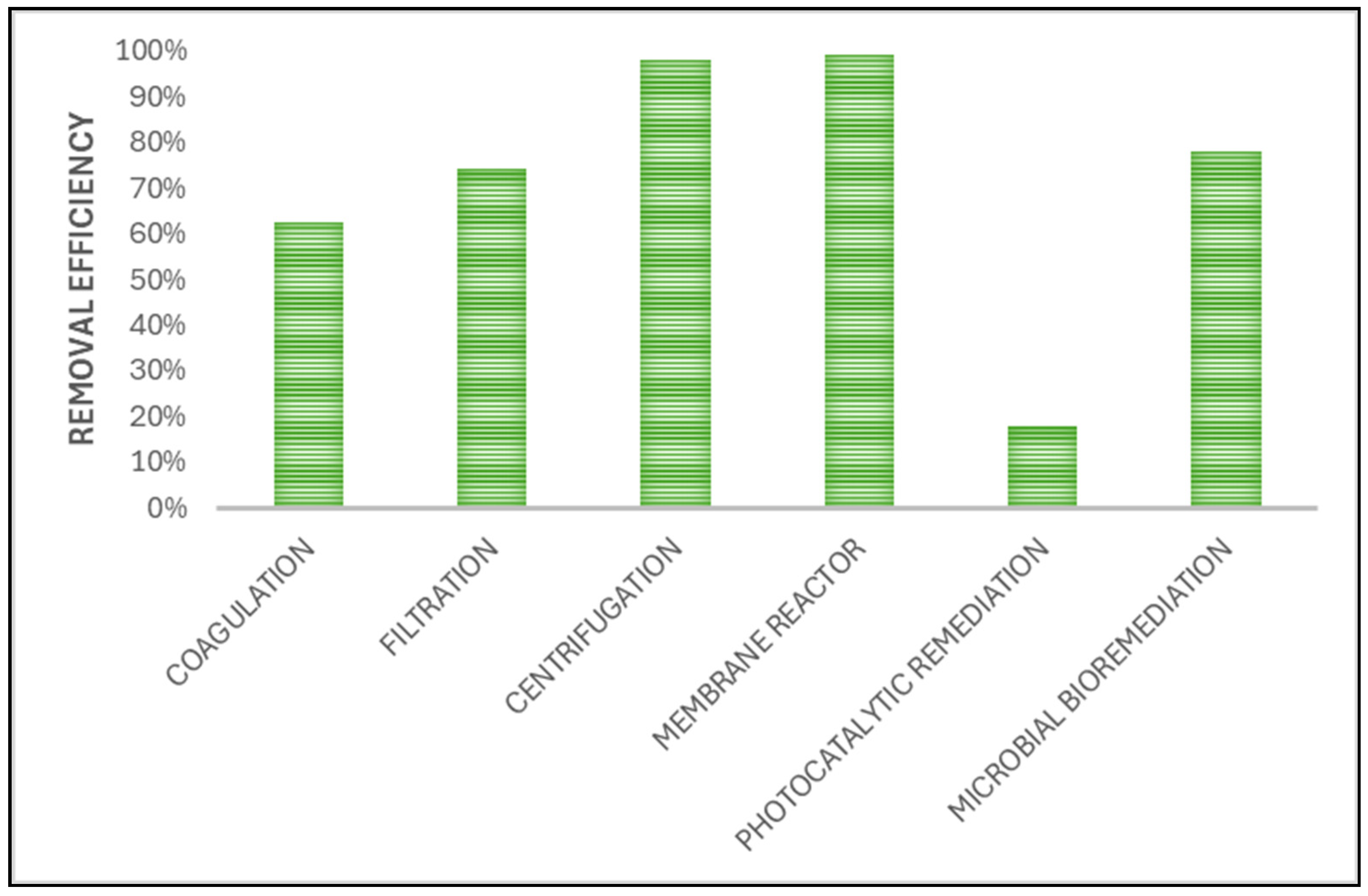

5. The Techniques for Removing MPs and NPs from Water

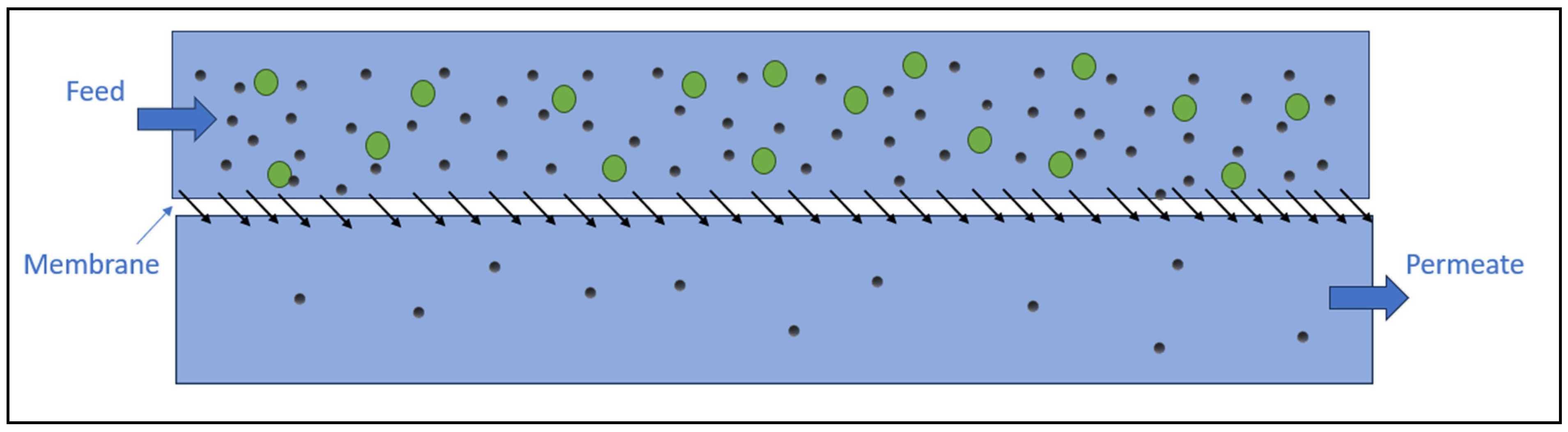

5.1. Membrane Filtration

5.1.1. Ultrafiltration

5.1.2. Reverse Osmosis

5.2. Centrifugation

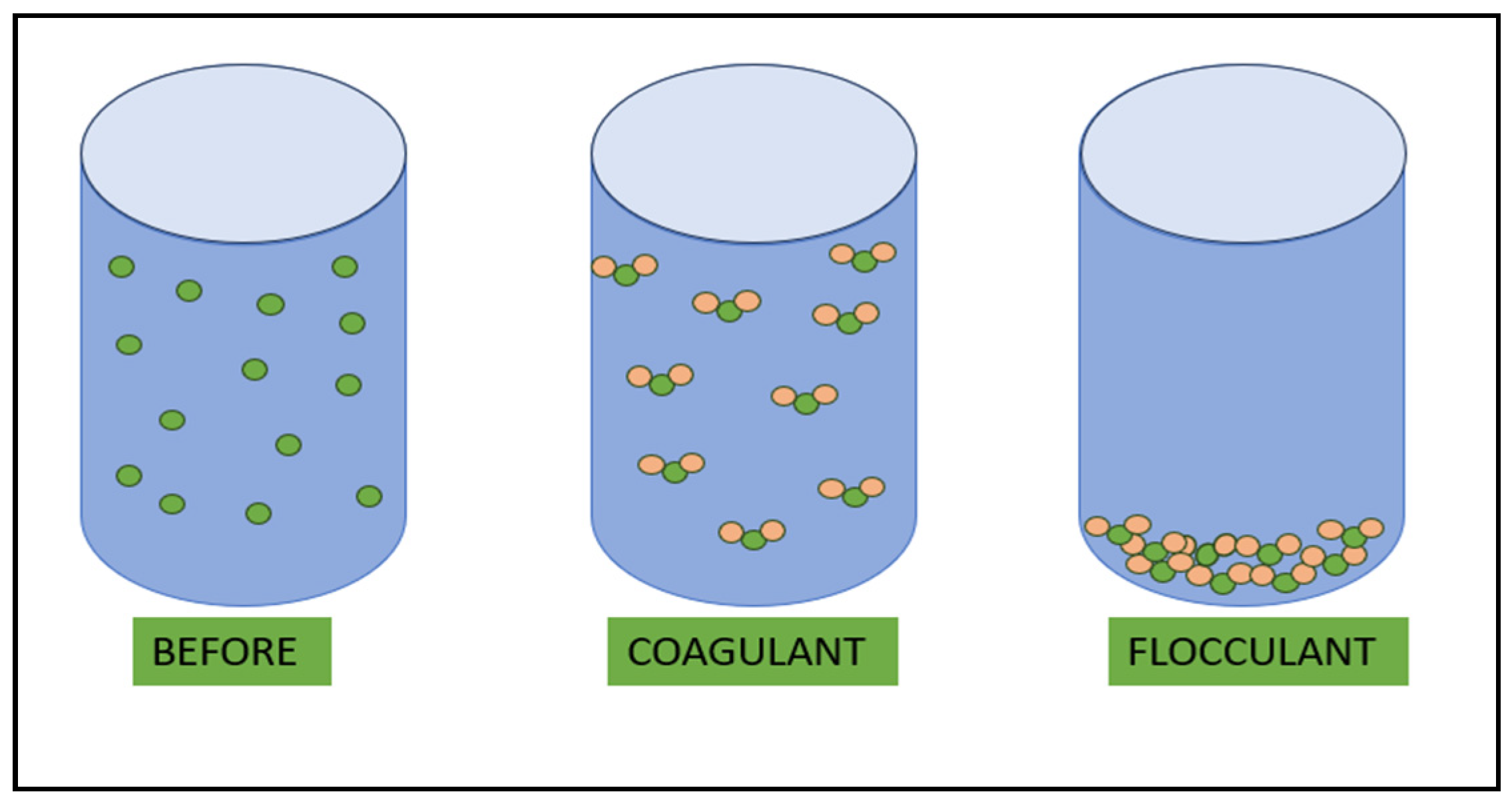

5.3. Flocculation

5.4. Photocatalytic Degradation

5.5. Bioreactors

5.6. Improved Adsorption

5.7. Utilizing Nanomaterials

6. MNPs (Properties, Synthesis Methods, Functionalization)

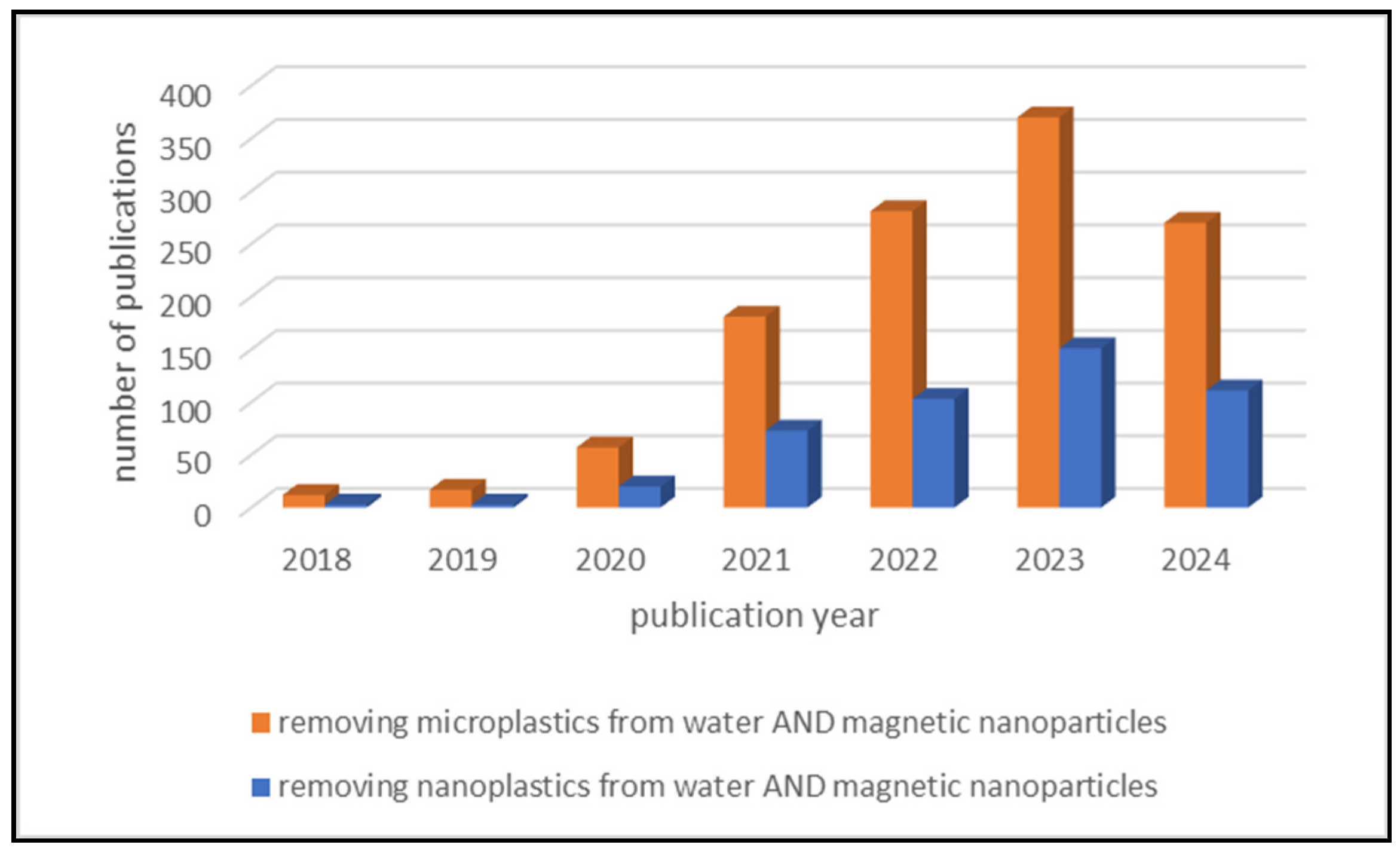

7. Published Scientific Articles on the Removal of MPs and NPs Using MNPs

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Singh, S.; Kumar Naik, T.S.S.; Anil, A.G.; Dhiman, J.; Kumar, V.; Dhanjal, D.S.; Aguilar-Marcelino, L.; Singh, J.; Ramamurthy, P.C. Micro (nano) plastics in wastewater: A critical review on toxicity risk assessment, behaviour, environmental impact and challenges. Chemosphere 2022, 290, 133169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivleva, N.P. Chemical Analysis of Microplastics and Nanoplastics: Challenges, Advanced Methods, and Perspectives. Chem. Rev. 2021, 121, 11886–11936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keerthana Devi, M.; Karmegam, N.; Manikandan, S.; Subbaiya, R.; Song, H.; Kwon, E.E.; Sarkar, B.; Bolan, N.; Kim, W.; Rinklebe, J.; et al. Removal of nanoplastics in water treatment processes: A review. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 845, 157168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, L.M.A.; Sheng, J.; Zimba, P.V.; Zhu, L.; Fadare, O.O.; Haley, C.; Wang, M.; Phillips, T.D.; Conkle, J.; Xu, W. Testing an Iron Oxide Nanoparticle-Based Method for Magnetic Separation of Nanoplastics and Microplastics from Water. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 2348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, L.; Wang, Y.; Liu, Z.; Huang, Q. Characteristics of equilibrium, kinetics studies for adsorption of Hg(II), Cu(II), and Ni(II) ions by thiourea-modified magnetic chitosan microspheres. J. Hazard. Mater. 2009, 161, 995–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, M.; Wang, J.; Xu, J.; Yang, Z.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, B. Novel synthetic method for magnetic sulphonated tubular trap for efficient mercury removal from wastewater. J. Colloid. Interface Sci. 2020, 565, 523–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmad, M.; Wang, J.; Xu, J.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, B. Magnetic tubular carbon nanofibers as efficient Cu(II) ion adsorbent from wastewater. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 252, 119825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, M.; Wu, F.; Cui, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, B. Preparation of Novel Bifunctional Magnetic Tubular Nanofibers and Their Application in Efficient and Irreversible Uranium Trap from Aqueous Solution. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2020, 8, 7825–7838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Fan, X.; Jia, X.; Chen, X.; Zhang, A.; Zhang, B.; Zhang, Q. Preparation of Magnetic Hyper-Cross-Linked Polymers for the Efficient Removal of Antibiotics from Water. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2018, 6, 210–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Zhao, X.; Wei, J.; Li, F. Sorption behavior of cesium from aqueous solution on magnetic hexacyanoferrate materials. Nucl. Eng. Des. 2014, 275, 322–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heo, Y.; Lee, E.-H.; Lee, S.-W. Adsorptive removal of micron-sized polystyrene particles using magnetic iron oxide nanoparticles. Chemosphere 2022, 307, 135672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kiran, B.R.; Kopperi, H.; Venkata Mohan, S. Micro/nano-plastics occurrence, identification, risk analysis and mitigation: Challenges and perspectives. Re/Views Environ. Sci. Bio/Technol. 2022, 21, 169–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asamoah, B.O.; Uurasjärvi, E.; Räty, J.; Koistinen, A.; Roussey, M.; Peiponen, K.E. Towards the Development of Portable and In Situ Optical Devices for Detection of Micro and Nanoplastics in Water: A Review on the Current Status. Polymer 2021, 13, 730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, H.; Park, B. Review of Microplastic Distribution, Toxicity, Analysis Methods, and Removal Technologies. Water 2021, 13, 2736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karbalaei, S.; Hanachi, P.; Walker, T.R.; Cole, M. Occurrence, sources, human health impacts and mitigation of microplastic pollution. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2018, 25, 36046–36063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yee, M.S.; Hii, L.W.; Looi, C.K.; Lim, W.M.; Wong, S.F.; Kok, Y.Y.; Tan, B.K.; Wong, C.Y.; Leong, C.O. Impact of Microplastics and Nanoplastics on Human Health. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blackburn, K.; Green, D. The potential effects of microplastics on human health: What is known and what is unknown. Ambio 2022, 51, 518–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carbery, M.; O’Connor, W.; Palanisami, T. Trophic transfer of microplastics and mixed contaminants in the marine food web and implications for human health. Environ. Int. 2018, 115, 400–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.-L.; Lee, Y.-H.; Chiu, I.-J.; Lin, Y.-F.; Chiu, H.-W. Potent Impact of Plastic Nanomaterials and Micromaterials on the Food Chain and Human Health. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 1727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, X.; Zhang, X.; Gao, W.; Zhang, Y.; He, D. Removal of microplastics from water by magnetic nano-Fe3O4. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 802, 149838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, D.; Tao, J.; Cheng, M.; Deng, R.; Chen, S.; Yin, L.; Li, R. Microplastics and nanoplastics in the environment: Macroscopic transport and effects on creatures. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 407, 124399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iyangbe, M.D. Critical Properties of Micro- and Nanoplastics for Potential Health Impact. Master’s Thesis, North Carolina Central University, Durham, NC, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Bermúdez, J.R.; Swarzenski, P.W. A microplastic size classification scheme aligned with universal plankton survey methods. MethodsX 2021, 8, 101516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Syberg, K.; Knudsen, C.M.H.; Tairova, Z.; Khan, F.R.; Shashoua, Y.; Geertz, T.; Pedersen, H.B.; Sick, C.; Mortensen, J.; Strand, J.; et al. Sorption of PCBs to environmental plastic pollution in the North Atlantic Ocean: Importance of size and polymer type. Case Stud. Chem. Environ. Eng. 2020, 2, 100062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alimi, O.S.; Farner, J.M.; Tufenkji, N. Exposure of nanoplastics to freeze-thaw leads to aggregation and reduced transport in model groundwater environments. Water Res. 2021, 189, 116533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, W.; Min, J.; Jiang, W.; Li, Y.; Zhang, W. Separation, characterization and identification of microplastics and nanoplastics in the environment. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 721, 137561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Man Thaiba, B.; Sedai, T.; Bastakoti, S.; Karki, A.; Anuradha, K.C.; Khadka, G.; Acharya, S.; Kandel, B.; Giri, B.; Bhakta Neupane, B. A review on analytical performance of micro- and nanoplastics analysis methods. Arab. J. Chem. 2023, 16, 104686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razeghi, N.; Hamidian, A.H.; Wu, C.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, M. Microplastic sampling techniques in freshwaters and sediments: A review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2021, 19, 4225–4252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campanale, C.; Savino, I.; Pojar, I.; Massarelli, C.; Uricchio, V. A Practical Overview of Methodologies for Sampling and Analysis of Microplastics in Riverine Environments. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Diehl, A.; Lewandowski, A.; Gopalakrishnan, K.; Baker, T. Removal efficiency of micro- and nanoplastics (180 nm–125 μm) during drinking water treatment. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 720, 137383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kundu, A.; Shetti, N.P.; Basu, S.; Reddy, K.R.; Nadagouda, M.N.; Aminabhavi, T.M. Identification and removal of micro- and nano-plastics: Efficient and cost-effective methods. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 421, 129816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prata, J.C.; da Costa, J.P.; Duarte, A.C.; Rocha-Santos, T. Methods for sampling and detection of microplastics in water and sediment: A critical review. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2019, 110, 150–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castelvetro, V.; Corti, A.; Biale, G.; Ceccarini, A.; Degano, I.; La Nasa, J.; Lomonaco, T.; Manariti, A.; Manco, E.; Modugno, F.; et al. New methodologies for the detection, identification, and quantification of microplastics and their environmental degradation by-products. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2021, 28, 46764–46780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, B.; Claveau-Mallet, D.; Hernandez, L.M.; Xu, E.G.; Farner, J.M.; Tufenkji, N. Separation and Analysis of Microplastics and Nanoplastics in Complex Environmental Samples. Acc. Chem. Res. 2019, 52, 858–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crichton, E.M.; Noël, M.; Gies, E.A.; Ross, P.S. A novel, density-independent and FTIR-compatible approach for the rapid extraction of microplastics from aquatic sediments. Anal. Methods 2017, 9, 1419–1428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grbic, J.; Nguyen, B.; Guo, E.; You, J.B.; Sinton, D.; Rochman, C.M. Magnetic Extraction of Microplastics from Environmental Samples. Environ. Sci. Technol. Lett. 2019, 6, 68–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greyling, G.; Pasch, H. Multidetector Thermal Field-Flow Fractionation for the Characterization of Vinyl Polymers in Binary Solvent Systems. Macromolecules 2017, 50, 569–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tadjiki, S.; Montaño, M.D.; Assemi, S.; Barber, A.; Ranville, J.; Beckett, R. Measurement of the Density of Engineered Silver Nanoparticles Using Centrifugal FFF-TEM and Single Particle ICP-MS. Anal. Chem. 2017, 89, 6056–6064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samanta, A.; Modak, N.; Datta, A.; Ganguly, R. Operating regimes of a magnetic split-flow thin (SPLITT) fractionation microfluidic device for immunomagnetic separation. Microfluid. Nanofluid. 2016, 20, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ornthai, M.; Siripinyanond, A.; Gale, B.K. Biased cyclical electrical field-flow fractionation for separation of submicron particles. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2016, 408, 855–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podzimek, S. Asymmetric Flow Field Flow Fractionation. In Encyclopedia of Analytical Chemistry: Applications, Theory and Instrumentation; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Contado, C. Field flow fractionation techniques to explore the “nano-world”. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2017, 409, 2501–2518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shim, W.J.; Hong, S.H.; Eo, S.E. Identification methods in microplastic analysis: A review. Anal. Methods 2017, 9, 1384–1391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.K.; Murphy, K.R.; Hur, J. Fluorescence Signatures of Dissolved Organic Matter Leached from Microplastics: Polymers and Additives. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2020, 54, 11905–11914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Auta, H.S.; Emenike, C.U.; Jayanthi, B.; Fauziah, S.H. Growth kinetics and biodeterioration of polypropylene microplastics by Bacillus sp. and Rhodococcus sp. isolated from mangrove sediment. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2018, 127, 15–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ter Halle, A.; Ladirat, L.; Martignac, M.; Mingotaud, A.F.; Boyron, O.; Perez, E. To what extent are microplastics from the open ocean weathered? Environ. Pollut. 2017, 227, 167–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zbyszewski, M.; Corcoran, P.L.; Hockin, A. Comparison of the distribution and degradation of plastic debris along shorelines of the Great Lakes, North America. J. Great Lakes Res. 2014, 40, 288–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, J.; Li, J.; Sun, C.; Jiang, F.; Ju, P.; Qu, L.; Zheng, Y.; He, C. Detection of microplastics in local marine organisms using a multi-technology system. Anal. Methods 2019, 11, 78–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.-M.; Wagner, J.; Ghosal, S.; Bedi, G.; Wall, S. SEM/EDS and optical microscopy analyses of microplastics in ocean trawl and fish guts. Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 603–604, 616–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, X.; Chen, B.; Li, Q.; Liu, N.; Xia, B.; Zhu, L.; Qu, K. Toxicities of polystyrene nano- and microplastics toward marine bacterium Halomonas alkaliphila. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 642, 1378–1385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, C.; Liu, Z.; Wang, C.; Li, S.; Kitamura, Y. Different interaction performance between microplastics and microalgae: The bio-elimination potential of Chlorella sp. L38 and Phaeodactylum tricornutum MASCC-0025. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 723, 138146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariano, S.; Tacconi, S.; Fidaleo, M.; Rossi, M.; Dini, L. Micro and Nanoplastics Identification: Classic Methods and Innovative Detection Techniques. Front. Toxicol. 2021, 3, 636640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Löder, M.G.J.; Kuczera, M.; Mintenig, S.; Lorenz, C.; Gerdts, G. Focal plane array detector-based micro-Fourier-transform infrared imaging for the analysis of microplastics in environmental samples. Environ. Chem. 2015, 12, 563–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, M.; Lindeque, P.; Fileman, E.; Halsband, C.; Goodhead, R.; Moger, J.; Galloway, T.S. Microplastic Ingestion by Zooplankton. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2013, 47, 6646–6655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Käppler, A.; Fischer, D.; Oberbeckmann, S.; Schernewski, G.; Labrenz, M.; Eichhorn, K.-J.; Voit, B. Analysis of environmental microplastics by vibrational microspectroscopy: FTIR, Raman or both? Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2016, 408, 8377–8391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araujo, C.F.; Nolasco, M.M.; Ribeiro, A.M.P.; Ribeiro-Claro, P.J.A. Identification of microplastics using Raman spectroscopy: Latest developments and future prospects. Water Res. 2018, 142, 426–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Majewsky, M.; Bitter, H.; Eiche, E.; Horn, H. Determination of microplastic polyethylene (PE) and polypropylene (PP) in environmental samples using thermal analysis (TGA-DSC). Sci. Total Environ. 2016, 568, 507–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Golebiewski, J.; Galeski, A. Thermal stability of nanoclay polypropylene composites by simultaneous DSC and TGA. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2007, 67, 3442–3447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, M.; Scholz-Böttcher, B.M. Simultaneous Trace Identification and Quantification of Common Types of Microplastics in Environmental Samples by Pyrolysis-Gas Chromatography–Mass Spectrometry. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2017, 51, 5052–5060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fries, E.; Dekiff, J.H.; Willmeyer, J.; Nuelle, M.-T.; Ebert, M.; Remy, D. Identification of polymer types and additives in marine microplastic particles using pyrolysis-GC/MS and scanning electron microscopy. Environ. Sci. Process. Impacts 2013, 15, 1949–1956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nuelle, M.-T.; Dekiff, J.H.; Remy, D.; Fries, E. A new analytical approach for monitoring microplastics in marine sediments. Environ. Pollut. 2014, 184, 161–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gambardella, C.; Morgana, S.; Ferrando, S.; Bramini, M.; Piazza, V.; Costa, E.; Garaventa, F.; Faimali, M. Effects of polystyrene microbeads in marine planktonic crustaceans. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2017, 145, 250–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Summers, S.; Henry, T.; Gutierrez, T. Agglomeration of nano- and microplastic particles in seawater by autochthonous and de novo-produced sources of exopolymeric substances. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2018, 130, 258–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gigault, J.; Pedrono, B.; Maxit, B.; Ter Halle, A. Marine plastic litter: The unanalyzed nano-fraction. Environ. Sci. Nano 2016, 3, 346–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browne, M.A.; Crump, P.; Niven, S.J.; Teuten, E.; Tonkin, A.; Galloway, T.; Thompson, R. Accumulation of Microplastic on Shorelines Woldwide: Sources and Sinks. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2011, 45, 9175–9179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jambeck, J.R.; Geyer, R.; Wilcox, C.; Siegler, T.R.; Perryman, M.; Andrady, A.; Narayan, R.; Law, K.L. Plastic waste inputs from land into the ocean. Science 2015, 347, 768–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horton, A.A.; Walton, A.; Spurgeon, D.J.; Lahive, E.; Svendsen, C. Microplastics in freshwater and terrestrial environments: Evaluating the current understanding to identify the knowledge gaps and future research priorities. Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 586, 127–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amobonye, A.; Bhagwat, P.; Raveendran, S.; Singh, S.; Pillai, S. Environmental Impacts of Microplastics and Nanoplastics: A Current Overview. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 768297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cole, M.; Lindeque, P.; Halsband, C.; Galloway, T.S. Microplastics as contaminants in the marine environment: A review. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2011, 62, 2588–2597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cárdenas-Alcaide, M.F.; Godínez-Alemán, J.A.; González-González, R.B.; Iqbal, H.M.N.; Parra-Saldívar, R. Environmental impact and mitigation of micro(nano)plastics pollution using green catalytic tools and green analytical methods. Green. Anal. Chem. 2022, 3, 100031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucas, N.; Bienaime, C.; Belloy, C.; Queneudec, M.; Silvestre, F.; Nava-Saucedo, J.-E. Polymer biodegradation: Mechanisms and estimation techniques—A review. Chemosphere 2008, 73, 429–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattsson, K.; Björkroth, F.; Karlsson, T.; Hassellöv, M. Nanofragmentation of Expanded Polystyrene Under Simulated Environmental Weathering (Thermooxidative Degradation and Hydrodynamic Turbulence). Front. Mar. Sci. 2021, 7, 578178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chamas, A.; Moon, H.; Zheng, J.; Qiu, Y.; Tabassum, T.; Jang, J.H.; Abu-Omar, M.; Scott, S.L.; Suh, S. Degradation Rates of Plastics in the Environment. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2020, 8, 3494–3511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, R.; Mukherjee, G.; Das Gupta, A.; Tribedi, P.; Sil, A.K. Isolation of a soil bacterium for remediation of polyurethane and low-density polyethylene: A promising tool towards sustainable cleanup of the environment. 3 Biotech. 2021, 11, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Z.; Shi, X.; Zhang, J.; Wu, L.; Wei, W.; Ni, B.-J. Nanoplastics are significantly different from microplastics in urban waters. Water Res. X 2023, 19, 100169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zettler, E.R.; Mincer, T.J.; Amaral-Zettler, L.A. Life in the “Plastisphere”: Microbial Communities on Plastic Marine Debris. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2013, 47, 7137–7146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mattsson, K.; Jocic, S.; Doverbratt, I.; Hansson, L.-A. Chapter 13—Nanoplastics in the Aquatic Environment. In Microplastic Contamination in Aquatic Environments; Zeng, E.Y., Ed.; Elsevier: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Lehner, R.; Weder, C.; Petri-Fink, A.; Rothen-Rutishauser, B. Emergence of Nanoplastic in the Environment and Possible Impact on Human Health. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2019, 53, 1748–1765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, Y.-B.; Xie, Z.-Y.; Hamid, N.; Tang, Q.-P.; Deng, J.-Y.; Luo, L.; Pei, D.-S. Recent advances in micro (nano) plastics in the environment: Distribution, health risks, challenges and future prospects. Aquat. Toxicol. 2023, 261, 106597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, L.; Xu, K.; Zhang, B.; Ye, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Jiang, W. Cellular internalization and release of polystyrene microplastics and nanoplastics. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 779, 146523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, Y.; Su, F.; Peng, L.; Liu, D. The life cycle of micro-nano plastics in domestic sewage. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 802, 149658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, P.; Lombi, E.; Zhao, F.-J.; Kopittke, P.M. Nanotechnology: A New Opportunity in Plant Sciences. Trends Plant Sci. 2016, 21, 699–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terepocki, A.K.; Brush, A.T.; Kleine, L.U.; Shugart, G.W.; Hodum, P. Size and dynamics of microplastic in gastrointestinal tracts of Northern Fulmars (Fulmarus glacialis) and Sooty Shearwaters (Ardenna grisea). Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2017, 116, 143–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, L.; Wu, S.; Lu, S.; Liu, M.; Song, Y.; Fu, Z.; Shi, H.; Raley-Susman, K.M.; He, D. Microplastic particles cause intestinal damage and other adverse effects in zebrafish Danio rerio and nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 619–620, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santillo, D.; Miller, K.; Johnston, P. Microplastics as contaminants in commercially important seafood species. Integr. Environ. Assess. Manag. 2017, 13, 516–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dobson, F.S.; Becker, P.H.; Arnaud, C.M.; Bouwhuis, S.; Charmantier, A. Plasticity results in delayed breeding in a long-distant migrant seabird. Ecol. Evol. 2017, 7, 3100–3109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Md Amin, R.; Sohaimi, E.S.; Anuar, S.T.; Bachok, Z. Microplastic ingestion by zooplankton in Terengganu coastal waters, southern South China Sea. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2020, 150, 110616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Courtene-Jones, W.; Quinn, B.; Gary, S.F.; Mogg, A.O.M.; Narayanaswamy, B.E. Microplastic pollution identified in deep-sea water and ingested by benthic invertebrates in the Rockall Trough, North Atlantic Ocean. Environ. Pollut. 2017, 231, 271–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larue, C.; Sarret, G.; Castillo-Michel, H.; Pradas del Real, A.E. A Critical Review on the Impacts of Nanoplastics and Microplastics on Aquatic and Terrestrial Photosynthetic Organisms. Small 2021, 17, 2005834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maity, S.; Pramanick, K. Perspectives and challenges of micro/nanoplastics-induced toxicity with special reference to phytotoxicity. Glob. Change Biol. 2020, 26, 3241–3250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yin, L.; Wen, X.; Huang, D.; Du, C.; Deng, R.; Zhou, Z.; Tao, J.; Li, R.; Zhou, W.; Wang, Z.; et al. Interactions between microplastics/nanoplastics and vascular plants. Environ. Pollut. 2021, 290, 117999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ali, S.S.; Elsamahy, T.; Koutra, E.; Kornaros, M.; El-Sheekh, M.; Abdelkarim, E.A.; Zhu, D.; Sun, J. Degradation of conventional plastic wastes in the environment: A review on current status of knowledge and future perspectives of disposal. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 771, 144719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stapleton, P.A. Microplastic and nanoplastic transfer, accumulation, and toxicity in humans. Curr. Opin. Toxicol. 2021, 28, 62–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, M.; Chen, H.; Sarsaiya, S.; Qin, S.; Liu, H.; Awasthi, M.K.; Kumar, S.; Singh, L.; Zhang, Z.; Bolan, N.S.; et al. Current research trends on micro- and nano-plastics as an emerging threat to global environment: A review. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 409, 124967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahman, A.; Sarkar, A.; Yadav, O.P.; Achari, G.; Slobodnik, J. Potential human health risks due to environmental exposure to nano- and microplastics and knowledge gaps: A scoping review. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 757, 143872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prata, J.C.; da Costa, J.P.; Lopes, I.; Duarte, A.C.; Rocha-Santos, T. Environmental exposure to microplastics: An overview on possible human health effects. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 702, 134455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schneider, M.; Stracke, F.; Hansen, S.; Schaefer, U.F. Nanoparticles and their interactions with the dermal barrier. Derm. Endocrinol. 2009, 1, 197–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brennecke, D.; Duarte, B.; Paiva, F.; Caçador, I.; Canning-Clode, J. Microplastics as vector for heavy metal contamination from the marine environment. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 2016, 178, 189–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason, S.A.; Welch, V.G.; Neratko, J. Synthetic Polymer Contamination in Bottled Water. Front. Chem. 2018, 6, 407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ge, H.; Yan, Y.; Wu, D.; Huang, Y.; Tian, F. Potential role of LINC00996 in colorectal cancer: A study based on data mining and bioinformatics. Onco Targets Ther. 2018, 11, 4845–4855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stapleton, P.A. Toxicological considerations of nano-sized plastics. AIMS Environ. Sci. 2019, 6, 367–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Porter, D.W.; Hubbs, A.F.; Mercer, R.R.; Wu, N.; Wolfarth, M.G.; Sriram, K.; Leonard, S.; Battelli, L.; Schwegler-Berry, D.; Friend, S.; et al. Mouse pulmonary dose- and time course-responses induced by exposure to multi-walled carbon nanotubes. Toxicology 2010, 269, 136–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohlwein, S.; Kappeler, R.; Kutlar Joss, M.; Künzli, N.; Hoffmann, B. Health effects of ultrafine particles: A systematic literature review update of epidemiological evidence. Int. J. Public Health 2019, 64, 547–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez, L.M.; Yousefi, N.; Tufenkji, N. Are There Nanoplastics in Your Personal Care Products? Environ. Sci. Technol. Lett. 2017, 4, 280–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouwstra, J.; Pilgram, G.; Gooris, G.; Koerten, H.; Ponec, M. New Aspects of the Skin Barrier Organization. Ski. Pharmacol. Appl. Ski. Physiol. 2004, 14, 52–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vogt, A.; Combadiere, B.; Hadam, S.; Stieler, K.M.; Lademann, J.; Schaefer, H.; Autran, B.; Sterry, W.; Blume-Peytavi, U. 40 nm, but not 750 or 1500 nm, Nanoparticles Enter Epidermal CD1a+ Cells after Transcutaneous Application on Human Skin. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2006, 126, 1316–1322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, M.; Zhang, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Song, B.; Zeng, G.; Hu, D.; Wen, X.; Ren, X. Recent advances in toxicological research of nanoplastics in the environment: A review. Environ. Pollut. 2019, 252, 511–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, L.; He, L.; Jiang, S.; Chen, J.; Zhou, C.; Qu, J.; Lu, Y.; Hong, P.; Sun, S.; Li, C. In situ surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy for detecting microplastics and nanoplastics in aquatic environments. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 728, 138449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, M.; Song, B.; Zhu, Y.; Zeng, G.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, Y.; Wen, X.; Chen, M.; Yi, H. Removal of microplastics via drinking water treatment: Current knowledge and future directions. Chemosphere 2020, 251, 126612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.B.; Kamcev, J.; Robeson, L.M.; Elimelech, M.; Freeman, B.D. Maximizing the right stuff: The trade-off between membrane permeability and selectivity. Science 2017, 356, eaab0530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enfrin, M.; Lee, J.; Le-Clech, P.; Dumée, L.F. Kinetic and mechanistic aspects of ultrafiltration membrane fouling by nano- and microplastics. J. Membr. Sci. 2020, 601, 117890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enders, K.; Lenz, R.; Stedmon, C.A.; Nielsen, T.G. Abundance, size and polymer composition of marine microplastics ≥ 10 μm in the Atlantic Ocean and their modelled vertical distribution. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2015, 100, 70–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramirez Arenas, L.; Ramseier Gentile, S.; Zimmermann, S.; Stoll, S. Fate and removal efficiency of polystyrene nanoplastics in a pilot drinking water treatment plant. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 813, 152623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMullen, L.D. Chapter 20—Remediation at the Water Treatment Plant. In Nitrogen in the Environment, 2nd ed.; Hatfield, J.L., Follett, R.F., Eds.; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Song, Z.; Liu, D.; Zhang, J.; Guo, L.; Fang, W.; Jin, J. Thermal treated amidoxime modified polymer of intrinsic microporosity (AOPIM-1) membranes for high permselectivity reverse osmosis desalination. Desalination 2023, 551, 116413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziajahromi, S.; Neale, P.A.; Rintoul, L.; Leusch, F.D. Wastewater treatment plants as a pathway for microplastics: Development of a new approach to sample wastewater-based microplastics. Water Res. 2017, 112, 93–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ly, Q.V.; Maqbool, T.; Zhang, Z.; Van Le, Q.; An, X.; Hu, Y.; Cho, J.; Li, J.; Hur, J. Characterization of dissolved organic matter for understanding the adsorption on nanomaterials in aquatic environment: A review. Chemosphere 2021, 269, 128690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bannick, C.G.; Szewzyk, R.; Ricking, M.; Schniegler, S.; Obermaier, N.; Barthel, A.K.; Altmann, K.; Eisentraut, P.; Braun, U. Development and testing of a fractionated filtration for sampling of microplastics in water. Water Res. 2019, 149, 650–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Z.; Huang, Z.; Liu, J.; Wu, E.; Zheng, Q.; Cui, L. Phase transition of Mg/Al-flocs to Mg/Al-layered double hydroxides during flocculation and polystyrene nanoplastics removal. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 406, 124697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azoulay, A.; Garzon, P.; Eisenberg, M.J. Comparison of the mineral content of tap water and bottled waters. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2001, 16, 168–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Batool, A.; Valiyaveettil, S. Surface functionalized cellulose fibers—A renewable adsorbent for removal of plastic nanoparticles from water. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 413, 125301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, E.; Shang, S.; Fu, Z.; Zhao, X.; Nan, X.; Du, Y.; Chen, X. Cotransport of naphthalene with polystyrene nanoplastics (PSNP) in saturated porous media: Effects of PSNP/naphthalene ratio and ionic strength. Chemosphere 2020, 245, 125602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakata, K.; Fujishima, A. TiO2 photocatalysis: Design and applications. J. Photochem. Photobiol. C Photochem. Rev. 2012, 13, 169–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castelvetro, V.; Corti, A.; Ceccarini, A.; Petri, A.; Vinciguerra, V. Nylon 6 and nylon 6,6 micro- and nanoplastics: A first example of their accurate quantification, along with polyester (PET), in wastewater treatment plant sludges. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 407, 124364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamrannejad, M.M.; Hasanzadeh, A.; Nosoudi, N.; Mai, L.; Babaluo, A.A. Photocatalytic degradation of polypropylene/TiO2 nano-composites. Mater. Res. 2014, 17, 1039–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dória, A.R.; Gonzaga, I.M.D.; Santos, G.O.S.; Pupo, M.; Silva, D.C.; Silva, R.S.; Rodrigo, M.A.; Eguiluz, K.I.B.; Salazar-Banda, G.R. Ultra-fast synthesis of Ti/Ru0.3Ti0.7O2 anodes with superior electrochemical properties using an ionic liquid and laser calcination. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 416, 129011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, I.; Ding, T.; Peng, C.; Naz, I.; Sun, H.; Li, J.; Liu, J.-f. Micro- and nanoplastics in wastewater treatment plants: Occurrence, removal, fate, impacts and remediation technologies—A critical review. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 423, 130205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; He, Q.; Guo, F.; Sun, X.; Zhang, J.; Chen, M.; Vymazal, J.; Chen, Y. Nanoplastics Disturb Nitrogen Removal in Constructed Wetlands: Responses of Microbes and Macrophytes. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2020, 54, 14007–14016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, C.B.; Kang, H.M.; Lee, Y.H.; Kim, M.S.; Lee, J.S.; Seo, J.S.; Wang, M.; Lee, J.S. Nanoplastic Ingestion Enhances Toxicity of Persistent Organic Pollutants (POPs) in the Monogonont Rotifer Brachionus koreanus via Multixenobiotic Resistance (MXR) Disruption. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2018, 52, 11411–11418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, G.; Huang, X.; Xu, H.; Wang, Q.; Wang, M.; Wang, Y.; Li, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Ye, Q.; Zhang, J. Removal of polystyrene nanoplastics from water by CuNi carbon material: The role of adsorption. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 820, 153190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, Y.; Na, Y.; Liang, N.; Zhao, L. Magnetic effervescent tablets containing deep eutectic solvent as a green microextraction for removal of polystyrene nanoplastics from water. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 2022, 188, 736–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Du, J.; Zhao, T.; Feng, B.; Bian, H.; Shan, S.; Meng, J.; Christie, P.; Wong, M.H.; Zhang, J. Removal of nanoplastics from aqueous solution by aggregation using reusable magnetic biochar modified with cetyltrimethylammonium bromide. Environ. Pollut. 2023, 318, 120897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binandeh, M. Performance of unique magnetic nanoparticles in biomedicine. Eur. J. Med. Chem. Rep. 2022, 6, 100072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, A.-H.; Salabas, E.L.; Schüth, F. Magnetic Nanoparticles: Synthesis, Protection, Functionalization, and Application. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2007, 46, 1222–1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Issa, B.; Obaidat, I.M.; Albiss, B.A.; Haik, Y. Magnetic nanoparticles: Surface effects and properties related to biomedicine applications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2013, 14, 21266–21305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farinha, P.; Coelho, J.M.P.; Reis, C.P.; Gaspar, M.M. A Comprehensive Updated Review on Magnetic Nanoparticles in Diagnostics. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 3432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Šafařík, I.; Šafaříková, M. Magnetic Nanoparticles and Biosciences. Monatshefte Für Chem./Chem. Mon. 2002, 133, 737–759. [Google Scholar]

- Kudr, J.; Haddad, Y.; Richtera, L.; Heger, Z.; Cernak, M.; Adam, V.; Zitka, O. Magnetic Nanoparticles: From Design and Synthesis to Real World Applications. Nanomaterials 2017, 7, 243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Materón, E.M.; Miyazaki, C.M.; Carr, O.; Joshi, N.; Picciani, P.H.S.; Dalmaschio, C.J.; Davis, F.; Shimizu, F.M. Magnetic nanoparticles in biomedical applications: A review. Appl. Surf. Sci. Adv. 2021, 6, 100163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, S.D.; Gwenin, V.V.; Gwenin, C.D. Magnetic Functionalized Nanoparticles for Biomedical, Drug Delivery and Imaging Applications. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 2019, 14, 188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Mendoza-Garcia, A.; Li, Q.; Sun, S. Organic Phase Syntheses of Magnetic Nanoparticles and Their Applications. Chem. Rev. 2016, 116, 10473–10512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, N.; Ji, H.; Yu, P.; Niu, J.; Farooq, M.U.; Akram, M.W.; Udego, I.O.; Li, H.; Niu, X. Surface Modification of Magnetic Iron Oxide Nanoparticles. Nanomaterials 2018, 8, 810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gambhir, R.P.; Rohiwal, S.S.; Tiwari, A.P. Multifunctional surface functionalized magnetic iron oxide nanoparticles for biomedical applications: A review. Appl. Surf. Sci. Adv. 2022, 11, 100303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikzamir, M.; Akbarzadeh, A.; Panahi, Y. An overview on nanoparticles used in biomedicine and their cytotoxicity. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2021, 61, 102316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díez, A.G.; Rincón-Iglesias, M.; Lanceros-Méndez, S.; Reguera, J.; Lizundia, E. Multicomponent magnetic nanoparticle engineering: The role of structure-property relationship in advanced applications. Mater. Today Chem. 2022, 26, 101220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerulová, K.; Kucmanová, A.; Sanny, Z.; Garaiová, Z.; Seiler, E.; Čaplovičová, M.; Čaplovič, Ľ.; Palcut, M. Fe3O4-PEI Nanocomposites for Magnetic Harvesting of Chlorella vulgaris, Chlorella ellipsoidea, Microcystis aeruginosa, and Auxenochlorella protothecoides. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 1786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nkurikiyimfura, I.; Wang, Y.; Safari, B.; Nshingabigwi, E. Temperature-dependent magnetic properties of magnetite nanoparticles synthesized via coprecipitation method. J. Alloys Compd. 2020, 846, 156344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ban, I.; Drofenik, M.; Makovec, D. The synthesis of iron–nickel alloy nanoparticles using a reverse micelle technique. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2006, 307, 250–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setia, A.; Mehata, A.K.; Vikas; Malik, A.K.; Viswanadh, M.K.; Muthu, M.S. Theranostic magnetic nanoparticles: Synthesis, properties, toxicity, and emerging trends for biomedical applications. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2023, 81, 104295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stergar, J.; Ferk, G.; Ban, I.; Drofenik, M.; Hamler, A.; Jagodič, M.; Makovec, D. The synthesis and characterization of copper–nickel alloy nanoparticles with a therapeutic Curie point using the microemulsion method. J. Alloys Compd. 2013, 576, 220–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majidi, S.; Zeinali Sehrig, F.; Farkhani, S.M.; Soleymani Goloujeh, M.; Akbarzadeh, A. Current methods for synthesis of magnetic nanoparticles. Artif. Cells Nanomed. Biotechnol. 2016, 44, 722–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, S.G.; Piao, Y.; Park, J.; Angappane, S.; Jo, Y.; Hwang, N.-M.; Park, J.-G.; Hyeon, T. Kinetics of Monodisperse Iron Oxide Nanocrystal Formation by “Heating-Up” Process. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007, 129, 12571–12584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixit, S.; Jeevanandam, P. Synthesis of Iron Oxide Nanoparticles by Thermal Decomposition Approach. Adv. Mater. Res. 2009, 67, 221–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unni, M.; Uhl, A.M.; Savliwala, S.; Savitzky, B.H.; Dhavalikar, R.; Garraud, N.; Arnold, D.P.; Kourkoutis, L.F.; Andrew, J.S.; Rinaldi, C. Thermal Decomposition Synthesis of Iron Oxide Nanoparticles with Diminished Magnetic Dead Layer by Controlled Addition of Oxygen. ACS Nano 2017, 11, 2284–2303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laurent, S.; Forge, D.; Port, M.; Roch, A.; Robic, C.; Vander Elst, L.; Muller, R.N. Magnetic Iron Oxide Nanoparticles: Synthesis, Stabilization, Vectorization, Physicochemical Characterizations, and Biological Applications. Chem. Rev. 2010, 110, 2574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrappa, K.; Adschiri, T. Hydrothermal technology for nanotechnology. Prog. Cryst. Growth Charact. Mater. 2007, 53, 117–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Wang, J.; Zhou, L.; Ma, W.; Zhang, D.; Ren, F.; Yan, H.; Qiu, G.; Liu, X. A Facile Solvothermal Synthesis and Magnetic Properties of MnFe2O4 Spheres with Tunable Sizes. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 2012, 95, 3569–3576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adewunmi, A.A.; Kamal, M.S.; Solling, T.I. Application of magnetic nanoparticles in demulsification: A review on synthesis, performance, recyclability, and challenges. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2021, 196, 107680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arruebo, M.; Fernández-Pacheco, R.; Ibarra, M.R.; Santamaría, J. Magnetic nanoparticles for drug delivery. Nano Today 2007, 2, 22–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chomoucka, J.; Drbohlavova, J.; Huska, D.; Adam, V.; Kizek, R.; Hubalek, J. Magnetic nanoparticles and targeted drug delivering. Pharmacol. Res. 2010, 62, 144–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, X.H.; Qian, X.; Mao, H.; Wang, A.Y.; Chen, Z.G.; Nie, S.; Shin, D.M. Targeted magnetic iron oxide nanoparticles for tumor imaging and therapy. Int. J. Nanomed. 2008, 3, 311–321. [Google Scholar]

- Qiao, R.; Fu, C.; Forgham, H.; Javed, I.; Huang, X.; Zhu, J.; Whittaker, A.K.; Davis, T.P. Magnetic iron oxide nanoparticles for brain imaging and drug delivery. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2023, 197, 114822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, I.; Sirohi, S.; Roy, K. Strategies for functionalization of magnetic nanoparticles for biomedical applications. Mater. Today Proc. 2023, 72, 2757–2767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohara, R.A.; Thorat, N.D.; Pawar, S.H. Role of functionalization: Strategies to explore potential nano-bio applications of magnetic nanoparticles. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 43989–44012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, D.T.; Kim, K.-S. Functionalization of magnetic nanoparticles for biomedical applications. Korean J. Chem. Eng. 2014, 31, 1289–1305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stergar, J.; Ban, I.; Drofenik, M.; Ferk, G.; Makovec, D. Synthesis and Characterization of Silica-Coated Cu1-xNix Nanoparticles. IEEE Trans. Magn. 2012, 48, 1344–1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da, X.; Li, R.; Li, X.; Lu, Y.; Gu, F.; Liu, Y. Synthesis and characterization of PEG coated hollow Fe3O4 magnetic nanoparticles as a drug carrier. Mater. Lett. 2022, 309, 131357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ban, I.; Markuš, S.; Gyergyek, S.; Drofenik, M.; Korenak, J.; Helix-Nielsen, C.; Petrinic, I. Synthesis of Poly-Sodium-Acrylate (PSA) Coated Magnetic Nanoparticles for Use in Forward Osmosis Draw. Solutions 2019, 9, 1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, R.; Xing, R.; Xu, Z.; Hou, Y.; Gao, S.; Sun, S. Synthesis, Functionalization, and Biomedical Applications of Multifunctional Magnetic Nanoparticles. Adv. Mater. 2010, 22, 2729–2742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Gao, Q.; Hong, G.; Ni, J. Synthesis of magnetite core–shell nanoparticles by surface-initiated ring-opening polymerization of l-lactide. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2008, 320, 1921–1927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaman, O.; Kuličková, J.; Herynek, V.; Koktan, J.; Maryško, M.; Dědourková, T.; Knížek, K.; Jirák, Z. Preparation of Mn-Zn ferrite nanoparticles and their silica-coated clusters: Magnetic properties and transverse relaxivity. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2017, 427, 251–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villa, S.; Riani, P.; Locardi, F.; Canepa, F. Functionalization of Fe₃O₄ NPs by Silanization: Use of Amine (APTES) and Thiol (MPTMS) Silanes and Their Physical Characterization. Materials 2016, 9, 826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umut, E.; Pineider, F.; Arosio, P.; Sangregorio, C.; Corti, M.; Tabak, F.; Lascialfari, A.; Ghigna, P. Magnetic, optical and relaxometric properties of organically coated gold–magnetite (Au–Fe3O4) hybrid nanoparticles for potential use in biomedical applications. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2012, 324, 2373–2379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fakurpur Shirejini, S.; Dehnavi, S.M.; Jahanfar, M. Potential of superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles coated with carbon dots as a magnetic nanoadsorbent for DNA isolation. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 2023, 190, 580–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaymaz, S.V.; Nobar, H.M.; Sarıgül, H.; Soylukan, C.; Akyüz, L.; Yüce, M. Nanomaterial surface modification toolkit: Principles, components, recipes, and applications. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2023, 322, 103035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angadi V, J.; K, M. 21—Present and future applications of magnetic nanoparticles in the field of medicine and biosensors. In Fundamentals and Industrial Applications of Magnetic Nanoparticles; Hussain, C.M., Patankar, K.K., Eds.; Woodhead Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Díaz-Hernández, A.; Gracida, J.; García-Almendárez, B.E.; Regalado, C.; Núñez, R.; Amaro-Reyes, A. Characterization of Magnetic Nanoparticles Coated with Chitosan: A Potential Approach for Enzyme Immobilization. J. Nanomater. 2018, 2018, 9468574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Las Nieves Piña, M.; Rodríguez, P.; Gutiérrez, M.S.; Quiñonero, D.; Morey, J.; Frontera, A. Adsorption and Quantification of Volatile Organic Compounds (VOCs) by using Hybrid Magnetic Nanoparticles. Chemistry 2018, 24, 12820–12826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Yu, Z.; Yang, T.; Xu, G.; Guan, Y.; Guo, C. Modified Fe3O4 magnetic nanoparticles for COD removal in oil field produced water and regeneration. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2021, 23, 101630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhary, A.; Khandelwal, N.; Ganie, Z.A.; Darbha, G.K. Influence of magnetite and its weathering originated maghemite and hematite minerals on sedimentation and transport of nanoplastics in the aqueous and subsurface environments. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 912, 169132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeap, S.P.; Ahmad, A.L.; Ooi, B.S.; Lim, J. Electrosteric stabilization and its role in cooperative magnetophoresis of colloidal magnetic nanoparticles. Langmuir 2012, 28, 14878–14891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, R.; Lin, S.; Jiang, W.; Yu, X.; Zhang, L.; Zhao, W.; Sui, Q. Effect of aggregation behavior on microplastic removal by magnetic Fe3O4 nanoparticles. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 898, 165431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaß, H.; Kloos, T.M.; Höfling, A.; Müller, L.; Rockmann, L.; Schubert, D.W.; Halik, M. Magnetic Removal of Micro- and Nanoplastics from Water—From 100 nm to 100 µm Debris Size. Small 2024, 20, 2305467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Wu, C.; Xiong, Z.; Liang, C.; Li, Z.; Liu, B.; Cao, Q.; Wang, J.; Tang, J.; Li, D. Self-driven magnetorobots for recyclable and scalable micro/nanoplastic removal from nonmarine waters. Sci. Adv. 2022, 8, eade1731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Liu, S.; Huang, K.; Qin, S.; Liang, B.; Wang, J. Preparation of magnetic Janus microparticles for the rapid removal of microplastics from water. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 903, 166627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.-P.; Huang, X.-H.; Chen, J.-N.; Dong, M.; Nie, C.-Z.; Qin, L. Modified superhydrophobic magnetic Fe3O4 nanoparticles for removal of microplastics in liquid foods. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 476, 146562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Duan, J.; Liu, R.; Petropoulos, E.; Feng, Y.; Xue, L.; Yang, L.; He, S. Efficient magnetic capture of PE microplastic from water by PEG modified Fe3O4 nanoparticles: Performance, kinetics, isotherms and influence factors. J. Environ. Sci. 2025, 147, 677–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babalar, M.; Siddiqua, S.; Sakr, M.A. A novel polymer coated magnetic activated biochar-zeolite composite for adsorption of polystyrene microplastics: Synthesis, characterization, adsorption and regeneration performance. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2024, 331, 125582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Zhang, S.; Su, Y.; Wu, D.; Zhao, Y.; Xie, B. Removal of microplastics from aqueous solutions by magnetic carbon nanotubes. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 406, 126804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Zou, X.; Wang, X.; Su, M.; Chen, C.; Sun, X.; Zhang, H. A preliminary study of the interactions between microplastics and citrate-coated silver nanoparticles in aquatic environments. J. Hazard. Mater. 2020, 385, 121601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhao, J.; Liu, Z.; Tian, S.; Lu, J.; Mu, R.; Yuan, H. Coagulation removal of microplastics from wastewater by magnetic magnesium hydroxide and PAM. J. Water Process Eng. 2021, 43, 102250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zhai, Y.; Wang, Z.; Liu, X.; Liu, X.; Zhou, Y.; Liu, G.; Xu, M. The removal characteristics and mechanisms of polystyrene microplastics with various induced photoaging degrees by CuFe2O4. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2023, 322, 124245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Huang, X.; Wang, L.; Zhao, X.; Yan, F.; Yang, Y.; Li, G.; Gao, P.; Ji, P. Removal of polystyrene nanoplastics from aqueous solutions using a novel magnetic material: Adsorbability, mechanism, and reusability. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 430, 133122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasanen, F.; Fuller, R.O.; Maya, F. Fast and simultaneous removal of microplastics and plastic-derived endocrine disruptors using a magnetic ZIF-8 nanocomposite. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 455, 140405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surette, M.C.; Mitrano, D.M.; Rogers, K.R. Extraction and concentration of nanoplastic particles from aqueous suspensions using functionalized magnetic nanoparticles and a magnetic flow cell. Microplast. Nanoplast. 2023, 3, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliva, J.; Valle-Garcia, L.S.; Garces, L.; Oliva, A.I.; Valadez-Renteria, E.; Hernandez-Bustos, D.A.; Campos-Amador, J.J.; Gomez-Solis, C. Using NIR irradiation and magnetic bismuth ferrite microparticles to accelerate the removal of polystyrene microparticles from the drinking water. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 345, 118784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakhteeva, Y.; Medvedeva, I.; Filinkova, M.; Byzov, I.; Minin, A.; Zhakov, S.; Uymin, M.; Patrakov, E.; Novikov, S.; Suntsov, A.; et al. Removal of microplastics from water by using magnetic sedimentation. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2023, 20, 11837–11850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, X.; Urso, M.; Kolackova, M.; Huska, D.; Pumera, M. Biohybrid Magnetically Driven Microrobots for Sustainable Removal of Micro/Nanoplastics from the Aquatic Environment. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2024, 34, 2307477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Sathish, C.I.; Guan, X.; Wang, S.; Palanisami, T.; Vinu, A.; Yi, J. Advances in magnetic materials for microplastic separation and degradation. J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 461, 132537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munir, N.; Javaid, A.; Abideen, Z.; Duarte, B.; Jarar, H.; El-Keblawy, A.; Sheteiwy, M.S. The potential of zeolite nanocomposites in removing microplastics, ammonia, and trace metals from wastewater and their role in phytoremediation. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2024, 31, 1695–1718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahendran, R.; Ramaswamy, S. Nanoplastics as Trojan Horses: Deciphering Complex Connections and Environmental Ramifications: A Review. Chem. Afr. 2024, 7, 2265–2282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Place | MPs Type | MPs Size | Profusion |

|---|---|---|---|

| The Netherlands (tap and surface water) | PS, PE | 50, 100, 200, 500, 1000 nm (PS), 90–106 µm | 260 mg/L |

| Denmark (fish sample) | PS, PE | 100 nm (PS), 200–9900 nm (PE) | 1.3 mg/g fish |

| USA (seawater) | PP, PE, PS, PA | ≤5 mm | 0.025 g/mL |

| South Korea (seawater and beach) | Expanded polystyrene (EPS) | ≤1 mm | 0–0.3 items/L (seawater), 631 items/L (beach) |

| China (surface sediment) | Rayon, PE, PP, PA, PET, PS, PMMA, PU | 34.97–4983.73 μm | 499.76 items/kg |

| Italy (shallow waters) | PE, PP, PS | ≤1 mm | 672–2175 items/kg |

| China (sediment) | HDPE, PET, PE, PS | ≤5 mm | 5.1–87.1 items/g sediment |

| China (sewage) | PET, PS, PP | 681.46 ± 528.73 μm | 0.59–12 items/L |

| China (freshwater bodies) | PES, rayon, PP, PA, nylon | 20 to 5000 μm | 0.9–2.4 items/L |

| Australia (shrimp) | PS, rayon | 0.190–4.214 mm | 0.40 ± 0.27 items/L |

| China (fishes) | PE, PP, PES | 20–500 μm | 0.3–5.3 items per fish |

| Germany (bottled water) | PET, PP | 1–500 μm | 0–253 items/L |

| Mexico (milk) | PES, polysulfone (PSU) | ≤5 mm | 3–11 items/L |

| Method | The Size of Removed NP [nm] | Removal Efficiency [%] | Limits |

|---|---|---|---|

| Filtration | 217–333 | 32–92 | Not suitable for larger particles, as they may remain in the fraction. |

| Ultrafiltration | ≤150 | 74 | Particles can evade treatment; the process can be time-consuming. |

| Flocculation | 217 | 77 | More studies are needed to determine the optimal parameters. |

| Centrifugation | 206 | 98 | Time-consuming process. |

| Photocatalytic degradation | ≤100 | 17.1 | The phototransformation of NPs can vary and the photo-reactive activity in water can be high. |

| Membrane bioreactor filtration | ≥2 | 99 | Proper hydraulic retention time. |

| Sample Types | MNPs | Characterization | Method | Particles Size of MPs, NPs | Removal Efficiency/Adsorption Capacity | Main Findings | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Solutions of MP (PS) | Fe3O4 | XRD, FTIR, DLS, SEM, TEM | Magnetic separation | 100, 500, 1000 nm | 83.1–92.9% in a 1 h period | Electropositive Fe3O4 MNPs and electronegative MPs efficient removal of MP. | [182] |

| Solutions of MPs (PE, PP, PS, PET) in pure, artificial, and environmental water samples | Magnetic nano-Fe3O4 | FTIR, SEM | Surface absorption, magnetic separation | 200–900 μm | 62.83–86.87% in a max. 240 min | Properties of MPs such as crystallinity, hydrophobicity, and density influence the removal efficiency. | [20] |

| microPS particles from the water | Magnetic iron oxide (Fe3O4) nanoparticles | TEM, FTIR | Adsorption process, desorption process | 0.08, 0.43, 0.7 and 1 μm | 42.0–93.7% depending on the concentration, total surface area and number of PS particles | Hydrophobic interactions are the main interactions involved in the aggregation of Fe3O4 with PS particles. | [11] |

| Salt and fresh water samples | Iron oxide nanoparticles with several polydimethylsiloxane hydrophobic coatings | SEM, TEM, SQUID, DLS, XRD, zeta potential | Absorption process | 2–5 mm; 100–1000 nm | 90.0–100% | Removed 100% of from 2–5 mm, and nearly 80% of NP particles from 100 nm to 1000 nm. | [4] |

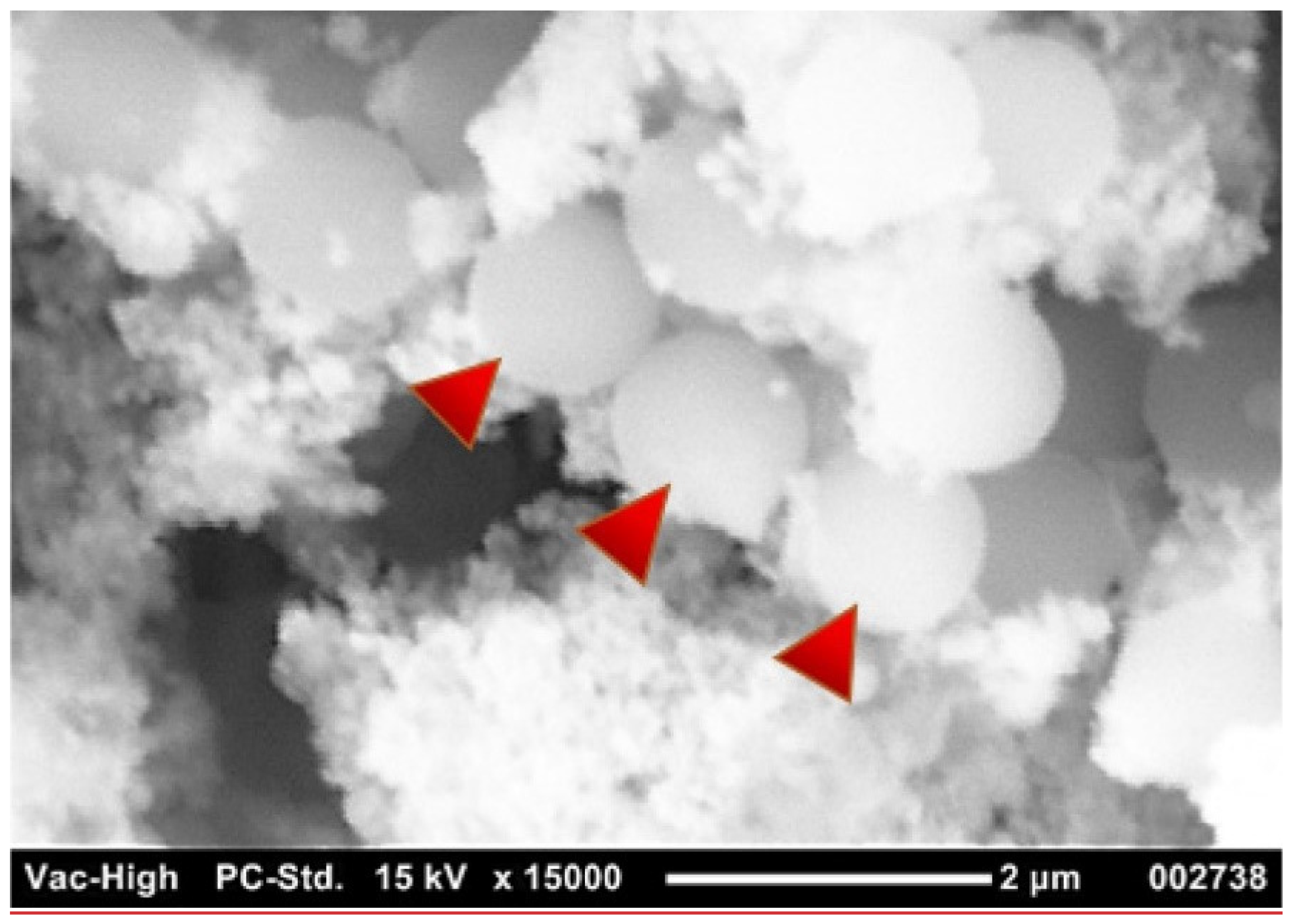

| Solution of PS, PMMA, ME | Modified superparamagnetic γ-Fe2O3, 9.6 nm | ATR-FTIR, TGA, DLS; SEM, | Magnetic removal | 100 nm–100 μm | Polymer types of 2.5–5 μm for the maximum removal yield in terms of removed MPs and NPs mass (up to 5.38 g/g SPION); MPs and NPs of 100 nm–1 μm in terms of highest numbers (up to 10 trillion MP and NP fragments per gram SPIONs) | If the size of the MPs is further increased, number as well as mass related efficiency is reduced as the specific surface area decreases rapidly. | [183] |

| Nonmarine waters in a recyclable and scalable way | SMR consists of an ion-exchange resin microsphere functionalized by superparamagnetic Fe3O4 nanoparticles | SEM, EDX, magnetic measurements, DLS, a confocal microscope | Dynamic adsorption process; magnetic removal | 0.2–40 μm | >90% over 100 treatment cycles | The magnetorobot shows sustainable removal efficiency of >90% over 100 treatment cycles. | [184] |

| Solutions of MPs (PS, PE) | Magnetic Janus microparticles (MJMs) synthesized via a modified Pickering emulsion method with aminated Fe3O4@SiO2 as the raw material | FTIR, TGA, SEM, contact angle analysis | Adsorption process | 10 μm | 92.08% for PS and 60.67% for PE in just 20 min | Kinetic and thermodynamic studies confirmed the remarkable rate and capacity of the MJMs. | [185] |

| MPs in five liquid food systems | Fe3O4@Cn (n = 12, 14, 16, 18), modified by different saturated fatty acids (C12, C14, C16, C18) | TEM, AFM, FTIR, XRD, XPS, VSM, BET, TGA, contact angle measurements | Nitrogen adsorption measurements | 100 nm | Fe3O4@C12 exhibited 92.89% adsorption efficiency | Fe3O4@C12 showed the desired adsorption efficiency. | [186] |

| PE MPs in water | Fe3O4; PEG/Fe3O4; PEI/Fe3O4; CA/Fe3O4 | FTIR, BET, zeta potential analysis, XRD | Magnetism adsorption | 13–149 μm | 2202.55 mg/g | The PEG/Fe3O4 exhibited a high magnetic capture efficiency of PE MPs in water. | [187] |

| PS MPs | magnetic activated biochar-zeolite composite (MACZ) coated with PEG and PEI (PMACZ) | SEM, EDX, BET, XRD, TGA, VSM | Adsorption | 2 and 15 μm | 736 mg/g and 769 mg/g for PMACZ on 2 μm and 15 μm MP | The efficiency and high cycling capacity of these adsorbents. | [188] |

| PE, PET, PA | Magnetic carbon nanotubes (M-CNTs) | UV-Vis, VSM, XRD, SEM, FTIR, XPS, zeta potential, TGA | Magnetic force | 48 μm | 100% | The adsorption of M-CNTs by PE -strong hydrophobicity of MPs, the adsorption of M-CNTs by PET–hydrophobic interaction and π-π electron conjugation, and π-π electron interaction. | [189] |

| PS NPs in water | CuNi carbon material (CuNi@C) | SEM, FTIR, XPS, XRD, BET | Adsorption process | 100 nm | 99.18% | After 4 cycles, CuNi@C can still remove ~75% of total PS NPs from water. | [130] |

| PE, PP, and PS in aquatic environments | Ag nanoparticles | UV-Vis, DLS, TEM, XRD, SEM, EDX | Adsorption process | 0.2–0.25 mm | 94.52% | Ag nanoparticles could be captured on the surface of PS MPs but coexisted with PE and PP MPs in water solutions. | [190] |

| PE in wastewater | magnetic magnesium hydroxide coagulant (MMHC) through the combination of Mg(OH)2 and Fe3O4 | SEM, FTIR, XRD, zeta potential | Adsorption process | ≤270 μm | 73.4–92.6% | Removal is the highest when the ratio of Mg2+ to OH− reaches 1:1. | [191] |

| PS MPs in water | CuFe2O4 | XRD, VSM, BET, FTIR, SEM, EDX, XPS, | Remove MPs with different photoaging degrees | 0.96–1.59 μm | 98.02% | Hydrogen bonding played a key role in the removal of pristine PS MPs and the destruction of C=O by Fe-OOH. | [192] |

| PS NPs in aqueous solutions | Fly ash modified with Fe ions | UV-Vis, FTIR, SEM-EDX, XRD, XPS, VSM | Adsorption process | 94.1% | Fly ash modified with Fe ions adsorbents has excellent reusability for PS NPs. | [193] | |

| PS MPs | A zeolitic imidazolate framework (ZIF-8) magnetic porous nanocomposite modulated with n-butylamine (nano-Fe@ZIF-8) | SEM, XRD, FESEM, BET, nitrogen adsorption-desorption measurements | Magnetic removal | 1.1 μm | ≥98% | The results illustrate the synthesis of a simple, environmentally friendly and high performing material for the fast removal of both soluble organic pollutants and microparticulated organic pollutants. | [194] |

| Metal-doped PS NPs in ultrapure water, synthetic freshwater, synthetic freshwater with a model natural organic matter isolate and synthetic marine water | Hydrophobically functionalized magnetic nanoparticles | EDX, DLS, SEM, XRD, | Magnetic separation flow cell | 229 nm | 56.1–84.9% | MNPs in combination with a flow-through system is a promising technique to extract NPs aqueous suspensions with various compositions. | [195] |

| PS NP/MPs in drinking water | Magnetic bismuth ferrite (BiFeO) microparticles | XRD, zeta potential measurements, | 70–11,000 nm | ≈95.5% in 90 min | Using photocatalysis + physical-adsorption is a feasible strategy to quickly remove MPs contaminants from the water. | [196] | |

| Polyethylene (PE) and PET MPs from model aqueous suspensions | Composite magnetic Fe-C-NH2 MNPs | DLS, SEM, optical microscopy, XRD, UV-Vis | Magnetic sedimentation | 5–30 μm | >99% | PE and PET MPs can be effectively separated from water by adding Fe-C-NH2 MNPs. | [197] |

| Amino–modified PS in aqueous suspension | Magnetic algae robots (algae cells with Fe3O4 bound on its surface) | SEM, EDX, XRD, zeta potential, magnetic measurements, fluorescence intensity measurements. | Removal under rotating magnetic field | 50 nm and 1.5 μm | 70–92% | Magnetic field driven algae-mased microrobots can be used for effective capture and removal of micro/nanoplastics from the aquatic environment. | [198] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Vohl, S.; Kristl, M.; Stergar, J. Harnessing Magnetic Nanoparticles for the Effective Removal of Micro- and Nanoplastics: A Critical Review. Nanomaterials 2024, 14, 1179. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano14141179

Vohl S, Kristl M, Stergar J. Harnessing Magnetic Nanoparticles for the Effective Removal of Micro- and Nanoplastics: A Critical Review. Nanomaterials. 2024; 14(14):1179. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano14141179

Chicago/Turabian StyleVohl, Sabina, Matjaž Kristl, and Janja Stergar. 2024. "Harnessing Magnetic Nanoparticles for the Effective Removal of Micro- and Nanoplastics: A Critical Review" Nanomaterials 14, no. 14: 1179. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano14141179

APA StyleVohl, S., Kristl, M., & Stergar, J. (2024). Harnessing Magnetic Nanoparticles for the Effective Removal of Micro- and Nanoplastics: A Critical Review. Nanomaterials, 14(14), 1179. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano14141179