Life-Cycle Risk Assessment of Second-Generation Cellulose Nanomaterials

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- Oral: a simulated digestion and intestinal tri-culture model was used to replicate the biological complexity of the human gut, including enterocytes, goblet cells, and immune cells;

- Inhalation: a co-culture of human lung epithelial cells and dendritic (immune) cells was used to replicate the epithelium of the human lung;

- Dermal: a co-culture of dermal epithelial cells and dermal fibroblasts was used to replicate the human epidermis.

- Pre-commercial safety screening of new chemistries early in the research and development process;

- Reducing the time and cost for conducting pre-commercial safety evaluations;

- Generating comprehensive physical, chemical, and toxicological data using NAMs to determine if CNs can be grouped together for the purpose of read-across, following established guidance for NMs [21];

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. SbD Toolbox CN Synthesis and Characterization

2.2. SbD Toolbox Hazard Assessment

2.2.1. Human Intestinal System Model

2.2.2. Human Inhalation System Model

2.2.3. Human Dermal System Model

2.2.4. Cytotoxicity via Membrane Disruption

2.2.5. Cellular Pro-Inflammatory Response

2.2.6. Statistical Analysis

2.2.7. SbD Toolbox for Read-Across

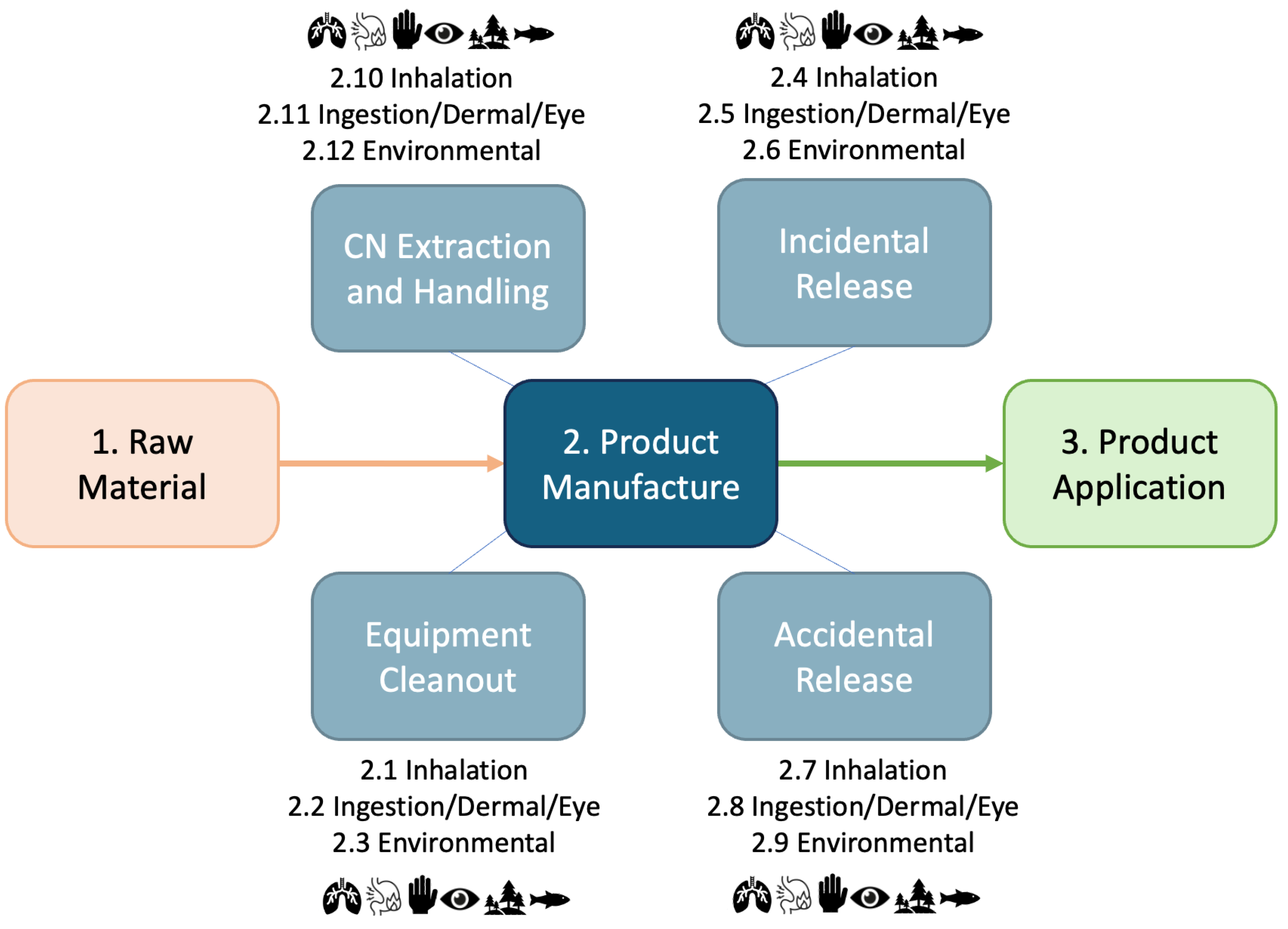

2.3. LCRA Overview

2.3.1. Case Study Development

2.3.2. Life-Cycle Stages and Assumptions

- Raw Material. This stage includes harvesting, chipping/shredding, and pulping of hardwood or softwood to produce bleached or unbleached cellulose pulp. The cellulose pulp is used as a raw material for CN production in later life-cycle stages.

- Product Manufacturing. The raw material is treated and processed to manufacture carboxylated or sulfated CNs. While production and chemical inputs differ by CN chemistry, all are produced in enclosed batch reactors with large-scale production capacity. The CNs are manufactured as low weight percentage (<2 wt %) aqueous dispersions. Production includes a drying step to produce CN powders (up to 100 wt %). The CNs are packaged, sold, and transported as powder.

- Product Application. The CNs are manufactured into commercial products with different intended applications. The handling, manufacture, and intended use of these products vary between each of the five selected CSs. Generally, CN materials are transported as a powder into a manufacturing facility. The CN powders are handled and may be redispersed into an aqueous suspension as part of product application. For CS1 (i.e., CN water filtration membrane) and CS2.1 (i.e., CN food packaging film), a CN formulation is prepared, and a casting and drying process is used to manufacture water filter membranes (up to 10 wt % CN; CS1) and food packaging films (up to 100 wt % CN; CS2.1). In CS2.2 (i.e., CN-coated food packaging), the CN formulation (2 wt % CN) is coated on paper/board food contact packaging using spray coating. The coating is dried/cured and may contain up to 100% CN. In CS2.3 (i.e., CN food packaging additive), the CN dispersion is mixed with traditional ingredients used to manufacture food contact paper/board. The CS assumes traditional paper/board production methods (e.g., screening, pressing, drying). In CS3 (i.e., CN food additive), food manufacturers may add CNs up to 5 wt % into food using high shear mixing, or similar processes in an open system. CNs are incorporated into food for a variety of technical effects including use as a stabilizer, emulsifier, thickener, or caloric reduction. Further details of the product application life-cycle stage for each CS are outlined in Table 3.

- Product Use. The five CSs involve CN-containing products for use in water filtration (CS1), food contact materials (CS2.1–2.3), and foods (CS3) and are detailed in Table 3. For CS1 (i.e., CN water filtration membrane), it is assumed the membrane is handled during instillation, and that is it primarily used for water filtration intended for consumption. The CN water filtration membrane may be used for large-scale filtration or for direct use by consumers. For CS2.1–2.3 (i.e., food contact applications), CNs are used as a single-use food packaging film, or as a coating or additive in food packaging paper/board. Under CS3, CNs are consumed as an additive in a variety of foods.

- Re-use/Recycling. After a typical service life which varies by CS (e.g., food contact applications in CS2.1–2.3 are single-use products), the CN products are re-used, recycled, or composted, or they may remain in use beyond their recommended lifespan. Recycling activities may include physical (e.g., shredding, tearing) or chemical processes (e.g., pulping). Re-purposing activities may include bioconversion processes. Alternatively, CN products may be composted (particularly for applications in food and food contact materials) at either consumer or industrial scale.

- Disposal. The original or reprocessed CN products are disposed of as waste. Consumer products typically end up in a landfill or incinerated for heat recovery. The products may also be discarded intentionally or unintentionally in an uncontrolled environment.

2.3.3. Exposure Scenario Development

2.3.4. Exposure Scenario Ranking

- Directness of exposure, which relates to the potential for direct contact of CNs (i.e., how easily particles are released);

- Magnitude, which relates to the relative degree of exposure based on the percentage of CN in the product;

- Likelihood, which prioritizes intentional exposures over unintentional or accidental ones;

- Frequency, an estimate of how often an exposure is expected.

2.3.5. Exposure Assessment

2.3.6. Hazard Assessment

2.3.7. Qualitative Health and Environmental Risk Characterization

3. Results

3.1. Exposure Scenario Development and Ranking

3.2. Exposure Scenario Ranking Results

3.3. High Ranking Exposure Scenarios Common to All Five CSs

| Life-Cycle Stage | LCSC | LCSN | SN | Scenario | Receptor | ER | DE | M | L | F | Score | Rank |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Product Manufacturing | PM | 2 | 10 | Dried formulation extraction and handling (for powder NC ingredients) | occupational | inhalation | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 12 | 1 |

| Product Manufacturing | PM | 2 | 11 | Dried formulation extraction and handling (for powder NC ingredients) | occupational | ingestion/dermal/eye | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 12 | 1 |

| Product Application | PA | 3 | 1 | Transfer CN from synthesis to application facility (e.g., handling, packaging) | occupational | inhalation | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 12 | 1 |

| Product Application | PA | 3 | 2 | Transfer CN from synthesis to application facility (e.g., handling, packaging) | occupational | ingestion/dermal/eye | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 12 | 1 |

| Product Application | PA | 3 | 6 | CN rehydration (if powder NC ingredient) | occupational | inhalation | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 12 | 1 |

| Product Application | PA | 3 | 7 | CN rehydration (if powder NC ingredient) | occupational | ingestion/dermal/eye | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 12 | 1 |

| Product Application | PA | 3 | 19 | CN drying (membrane formation) | occupational | ingestion/dermal/eye | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 11 | 2 |

| Product Application | PA | 3 | 21 | Surface treatment of CN membrane (functionalization, other) | occupational | ingestion/dermal/eye | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 11 | 2 |

| Re-use/Recycling | RR | 5 | 2 | Collection and transport of used membrane to re-use or composting facility | occupational | ingestion/dermal/eye | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 11 | 2 |

| Re-use/Recycling | RR | 5 | 7 | Composting used membrane | environmental | direct | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 11 | 2 |

| Re-use/Recycling | RR | 5 | 11 | Continued use (degraded membrane) | consumer | ingestion/dermal/eye | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 11 | 2 |

| Re-use/Recycling | RR | 5 | 12 | Continued use (degraded membrane) | environmental | direct | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 11 | 2 |

| Disposal | D | 6 | 5 | Long-term MSW landfill storage | environmental | direct | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 11 | 2 |

| Product Manufacturing | PM | 2 | 1 | Cleaning out synthesis equipment | occupational | inhalation | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 10 | 3 |

| Product Manufacturing | PM | 2 | 2 | Cleaning out synthesis equipment | occupational | ingestion/dermal/eye | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 10 | 3 |

| Product Application | PA | 3 | 3 | Deposition and formulation equipment cleanout | occupational | inhalation | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 10 | 3 |

| Product Application | PA | 3 | 4 | Deposition and formulation equipment cleanout | occupational | ingestion/dermal/eye | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 10 | 3 |

| Product Application | PA | 3 | 8 | CN formulation preparation (e.g., mixing with other ingredients, homogenizing, other) | occupational | inhalation | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 10 | 3 |

| Product Application | PA | 3 | 9 | CN formulation preparation (e.g., mixing with other ingredients, homogenizing, other) | occupational | ingestion/dermal/eye | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 10 | 3 |

| Product Application | PA | 3 | 10 | CN casting to form membrane | occupational | inhalation | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 10 | 3 |

| Product Application | PA | 3 | 11 | CN casting to form membrane | occupational | ingestion/dermal/eye | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 10 | 3 |

| Product Use | PU | 4 | 4 | Use of membrane to filter drinking water | occupational | ingestion | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 10 | 3 |

| Product Use | PU | 4 | 5 | Use of membrane to filter drinking water | consumer | ingestion | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 10 | 3 |

| Product Use | PU | 4 | 6 | Use of membrane to filter drinking water | environmental | direct | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 10 | 3 |

| Re-use/Recycling | RR | 5 | 4 | Composting used membrane | occupational | ingestion/dermal/eye | 2 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 10 | 3 |

| Product Application | PA | 3 | 18 | CN drying (membrane formation) | occupational | inhalation | 2 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 9 | 4 |

| Product Application | PA | 3 | 20 | Surface treatment of CN membrane (functionalization, other) | occupational | inhalation | 2 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 9 | 4 |

| Product Use | PU | 4 | 2 | Membrane handling, installation, and removal | occupational | ingestion/dermal/eye | 2 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 9 | 4 |

| Product Use | PU | 4 | 3 | Membrane handling, installation, and removal | consumer | ingestion/dermal/eye | 2 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 9 | 4 |

| Re-use/Recycling | RR | 5 | 1 | Collection and transport of used membrane to re-use or composting facility | occupational | inhalation | 2 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 9 | 4 |

| Product Manufacturing | PM | 2 | 4 | Incidental release of CN from synthesis equipment | occupational | inhalation | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 8 | 5 |

| Product Manufacturing | PM | 2 | 5 | Incidental release of CN from synthesis equipment | occupational | ingestion/dermal/eye | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 8 | 5 |

| Product Manufacturing | PM | 2 | 6 | Incidental release of CN from synthesis equipment | environmental | direct | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 8 | 5 |

| Product Application | PA | 3 | 12 | Incidental release of CN from deposition equipment | occupational | inhalation | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 8 | 5 |

| Product Application | PA | 3 | 13 | Incidental release of CN from deposition equipment | occupational | ingestion/dermal/eye | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 8 | 5 |

| Re-use/Recycling | RR | 5 | 6 | Composting used membrane | consumer | ingestion/dermal/eye | 2 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 8 | 5 |

| Re-use/Recycling | RR | 5 | 9 | Bioconversion (anaerobic digestion) | occupational | ingestion/dermal/eye | 2 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 8 | 5 |

| Re-use/Recycling | RR | 5 | 10 | Bioconversion (anaerobic digestion) | environmental | direct | 2 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 8 | 5 |

| Disposal | D | 6 | 1 | Collection and transport to final end-of-life location | occupational | ingestion/dermal/eye | 2 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 8 | 5 |

| Disposal | D | 6 | 2 | Collection and transport to final end-of-life location | environmental | direct | 2 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 8 | 5 |

| Disposal | D | 6 | 3 | Incineration or heat recovery | occupational | inhalation | 2 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 8 | 5 |

| Disposal | D | 6 | 4 | Incineration or heat recovery | environmental | direct | 2 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 8 | 5 |

| Disposal | D | 6 | 6 | Membrane discarded in uncontrolled environment | environmental | direct | 2 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 8 | 5 |

| Product Manufacturing | PM | 2 | 3 | Cleaning out synthesis equipment | environmental | direct | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 7 | 6 |

| Product Manufacturing | PM | 2 | 7 | Accidental spill of CN from synthesis equipment | occupational | inhalation | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 7 | 6 |

| Product Manufacturing | PM | 2 | 8 | Accidental spill of CN from synthesis equipment | occupational | ingestion/dermal/eye | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 7 | 6 |

| Product Manufacturing | PM | 2 | 9 | Accidental spill of CN from synthesis equipment | environmental | direct | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 7 | 6 |

| Product Application | PA | 3 | 5 | Deposition and formulation equipment cleanout | environmental | direct | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 7 | 6 |

| Product Application | PA | 3 | 14 | Incidental release of CN from deposition equipment | environmental | direct | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 7 | 6 |

| Product Application | PA | 3 | 15 | Accidental spill of CN from deposition equipment | occupational | inhalation | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 7 | 6 |

| Product Application | PA | 3 | 16 | Accidental spill of CN from deposition equipment | occupational | ingestion/dermal/eye | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 7 | 6 |

| Product Application | PA | 3 | 17 | Accidental spill of CN from deposition equipment | environmental | direct | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 7 | 6 |

| Product Use | PU | 4 | 1 | Membrane handling, installation, and removal | occupational | inhalation | 2 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 7 | 6 |

| Re-use/Recycling | RR | 5 | 3 | Composting used membrane | occupational | inhalation | 2 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 7 | 6 |

| Re-use/Recycling | RR | 5 | 5 | Composting used membrane | consumer | inhalation | 2 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 7 | 6 |

| Re-use/Recycling | RR | 5 | 8 | Bioconversion (anaerobic digestion) | occupational | inhalation | 2 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 7 | 6 |

| Raw Material | RM | 1 | 1 | Harvesting, chipping/shredding, pulping softwood or hardwood | occupational | 0 | 7 |

3.4. High Ranking Exposure Scenarios Unique to Specific Case Studies

| Exposure Scenarios | Exposure Scenario Ranking | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CS | Life-Cycle Stage | LCSC | LCSN | SN | Scenario | R | ER | DE | M | L | F | Score | Rank |

| Top Ranking Exposure Scenarios | |||||||||||||

| All CSs | Product Manufacturing | PM | 2 | 10 | Dried formulation extraction and handling (for powder CN ingredients) | O | I | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 12 | 1 |

| All CSs | Product Manufacturing | PM | 2 | 11 | Dried formulation extraction and handling (for powder CN ingredients) | O | I/D/E | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 12 | 1 |

| All CSs | Product Application | PA | 3 | 1 | Transfer CN from synthesis to application facility (e.g., handling, packaging) | O | I | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 12 | 1 |

| All CSs | Product Application | PA | 3 | 2 | Transfer CN from synthesis to application facility (e.g., handling, packaging) | O | I/D/E | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 12 | 1 |

| All CSs | Product Application | PA | 3 | 6 | CN rehydration | O | I | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 12 | 1 |

| All CSs | Product Application | PA | 3 | 7 | CN rehydration | O | I/D/E | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 12 | 1 |

| Second Highest Ranked Exposure Scenarios | |||||||||||||

| CS1, 2.1, 2.2, 2.3 | Product Application | PA | 3 | 19 | CN drying (membrane/film/packaging formation) | O | I/D/E | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 11 | 2 |

| CS1, 2.1, 2.2, 2.3 | Product Application | PA | 3 | 21 | Surface treatment of CN membrane/film/packaging (e.g., functionalization, other) | O | I/D/E | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 11 | 2 |

| All CSs | Re-use/Recycling | RR | 5 | 2 | Collection and transport of used CN product to re-use or composting facility | O | I/D/E | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 11 | 2 |

| All CSs | Re-use/Recycling | RR | 5 | 7 | Composting used CN products | E | D | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 11 | 2 |

| All CSs | Disposal | D | 6 | 6 | Long-term MSW landfill storage of CN products | E | D | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 11 | 2 |

| Third Highest Ranked Exposure Scenarios | |||||||||||||

| All CSs | Product Manufacturing | PM | 2 | 1 | Cleaning out synthesis equipment | O | I | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 10 | 3 |

| All CSs | Product Manufacturing | PM | 2 | 2 | Cleaning out synthesis equipment | O | I/D/E | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 10 | 3 |

| All CSs | Product Application | PA | 3 | 3 | CN product manufacturing equipment cleanout | O | I | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 10 | 3 |

| All CSs | Product Application | PA | 3 | 4 | CN product manufacturing equipment cleanout | O | I/D/E | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 10 | 3 |

| All CSs | Product Application | PA | 3 | 8 | CN formulation preparation (e.g., mixing with other ingredients, homogenizing, other) | O | I | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 10 | 3 |

| All CSs | Product Application | PA | 3 | 9 | CN formulation preparation (e.g., mixing with other ingredients, homogenizing, other) | O | I/D/E | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 10 | 3 |

| CS1, 2.1, 2.3 | Product Application | PA | 3 | 10 | CN casting to form membrane/film/packaging | O | I | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 10 | 3 |

| CS1, 2.1, 2.3 | Product Application | PA | 3 | 11 | CN casting to form membrane/film/packaging | O | I/D/E | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 10 | 3 |

| All CSs | Re-use/Recycling | RR | 5 | 4 | Composting used CN product | O | I/D/E | 2 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 10 | 3 |

| Exposure Scenarios | Exposure Scenario Ranking | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CS | Life-Cycle Stage | LCSC | LCSN | SN | Scenario | R | ER | DE | M | L | F | Score | Rank |

| CS1 (Water Filtration Membrane; TCNF and PCCNF) Top Ranking Scenarios | |||||||||||||

| CS1 | Re-use/Recycling | RR | 5 | 11 | Continued use (degraded membrane) | C | I/D/E | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 11 | 2 |

| CS1 | Re-use/Recycling | RR | 5 | 12 | Continued use (degraded membrane) | E | D | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 11 | 2 |

| CS1 | Product Use | PU | 4 | 4 | Use of membrane to filter drinking water | O | Ingest. | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 10 | 3 |

| CS1 | Product Use | PU | 4 | 5 | Use of membrane to filter drinking water | C | Ingest. | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 10 | 3 |

| CS1 | Product Use | PU | 4 | 6 | Use of membrane to filter drinking water | E | D | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 10 | 3 |

| Food Contact CSs (CS2.1, 2.2, 2.3) | |||||||||||||

| CS2.1, 2.2, 2.3 | Product Application | PA | 3 | 23 | Physical treatment of CN packaging (e.g., forming, bending, other) | O | I/D/E | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 11 | 2 |

| CS2.1, 2.2, 2.3 | Product Use | PU | 4 | 3 | Food packaging handling/interaction (release) | C | I/D/E | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 11 | 2 |

| CS2.1, 2.2, 2.3 | Product Use | PU | 4 | 1 | Food packaging use (release, migration to food) | C | Ingest. | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 11 | 2 |

| CS2.1, 2.2, 2.3 | Re-use/Recycling | RR | 5 | 4 | Recycling activities: Physical breakdown of used food packaging (e.g., tearing) | O | I/D/E | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 11 | 2 |

| CS2.1, 2.2, 2.3 | Re-use/Recycling | RR | 5 | 6 | Recycling activities: Chemical breakdown of used food packaging (e.g., pulping) | O | I/D/E | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 11 | 2 |

| CS2.2 (Food Packaging Coating; SCNF) Top Ranking Scenarios | |||||||||||||

| CS2.2 | Product Application | PA | 3 | 10 | CN formulation applied via spraying coating on paper food contact material | O | I | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 10 | 3 |

| CS2.2 | Product Application | PA | 3 | 11 | CN formulation applied via spraying coating on paper food contact material | O | I/D/E | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 10 | 3 |

| CS3 (Food Additive; TCNF and PCCNF) Top Ranking Scenarios | |||||||||||||

| CS3 | Product Use | PU | 4 | 1 | Food handling and consumption | C | Ingest. | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 10 | 2 |

| CS3 | Product Use | PU | 4 | 2 | Food handling and consumption | C | D/E | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 10 | 2 |

| CS3 | Re-use/Recycling | RR | 5 | 2 | Production of food waste into animal feed | E | D | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 10 | 2 |

3.5. Potential Exposures Across the Product Life-Cycle

3.6. Exposure Assessment Results

3.6.1. Occupational Exposures

3.6.2. Releases from CN Composites

- (1)

- Releases from Carboxylated CN Composites

- (2)

- Releases from Sulfated CN Composites

3.6.3. Environmental Exposures, Fate, and Persistence

- (1)

- Carboxylated CNs

- (2)

- Sulfated CNs

3.6.4. Exposure Assessment Limitations

3.7. Hazard Assessment: SbD Toolbox

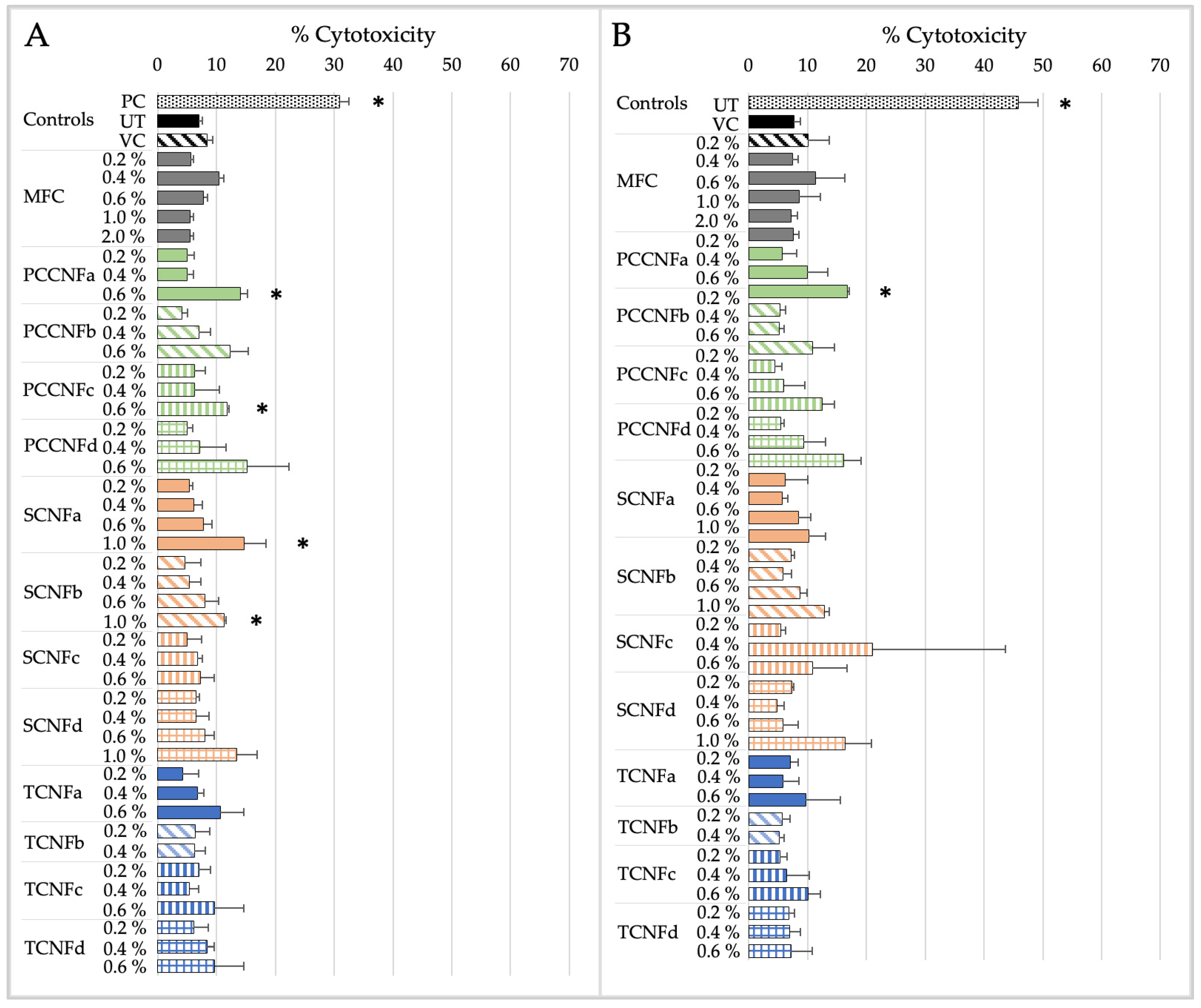

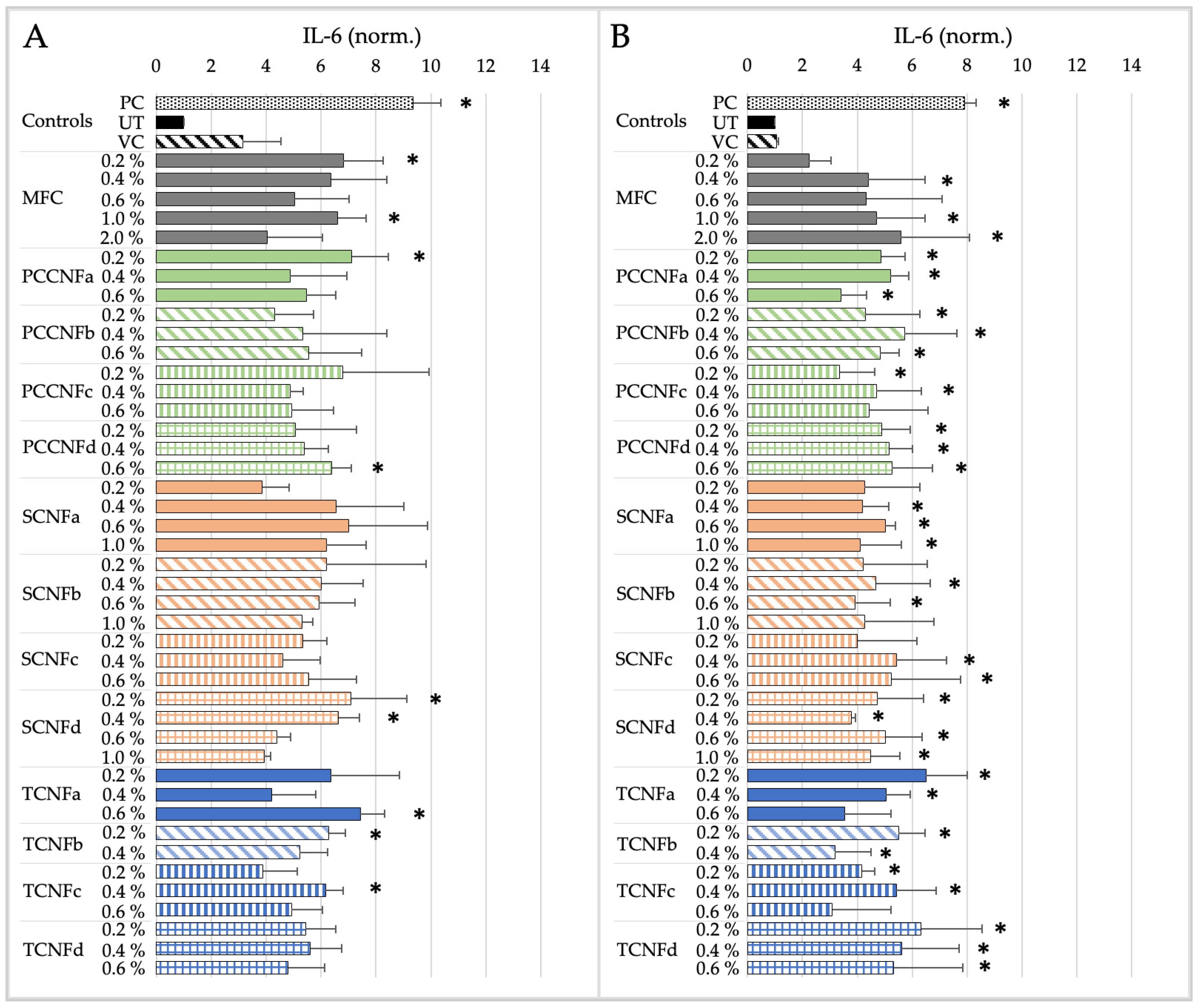

3.7.1. Oral Hazard Evaluation

3.7.2. Inhalation Hazard Evaluation

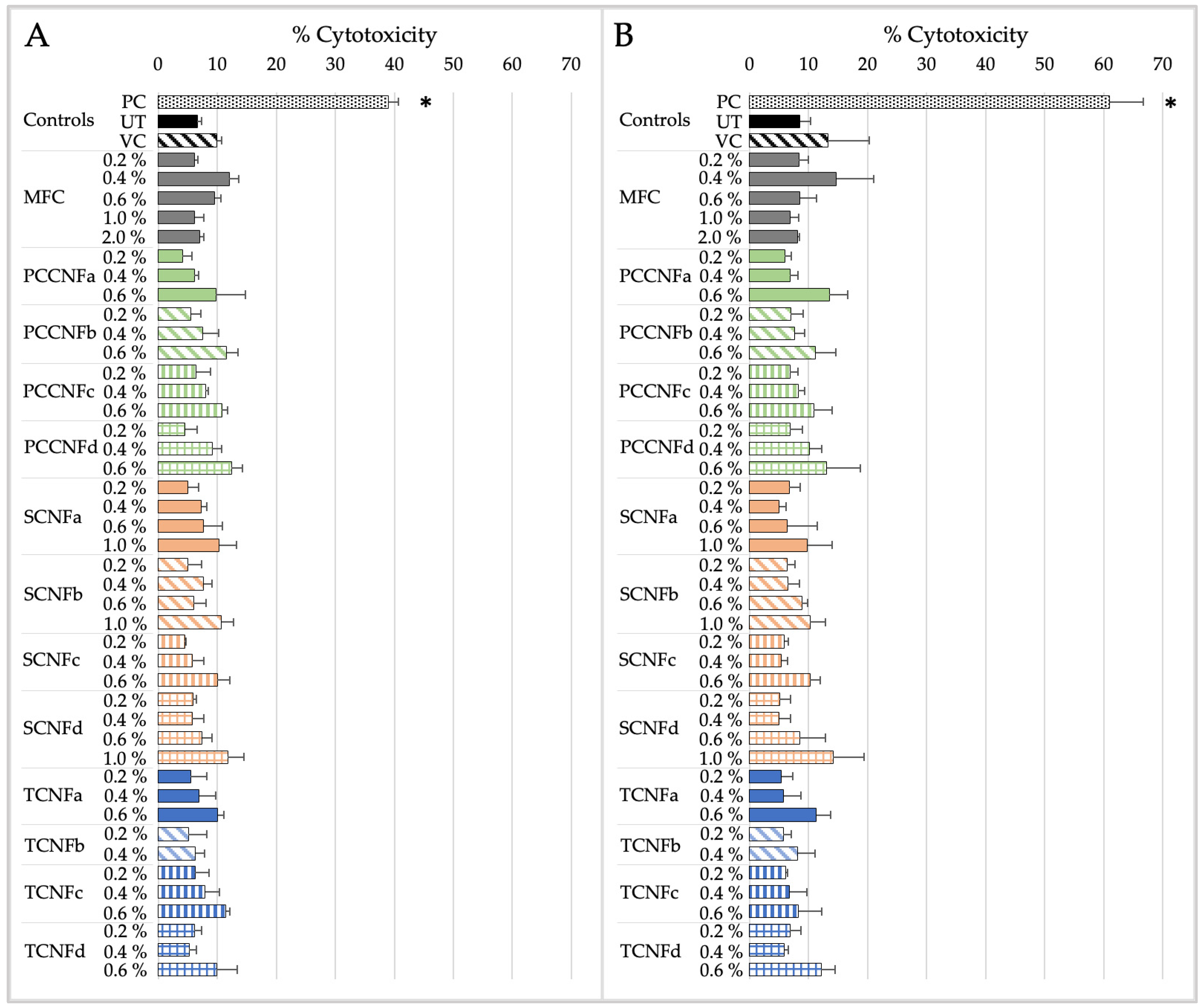

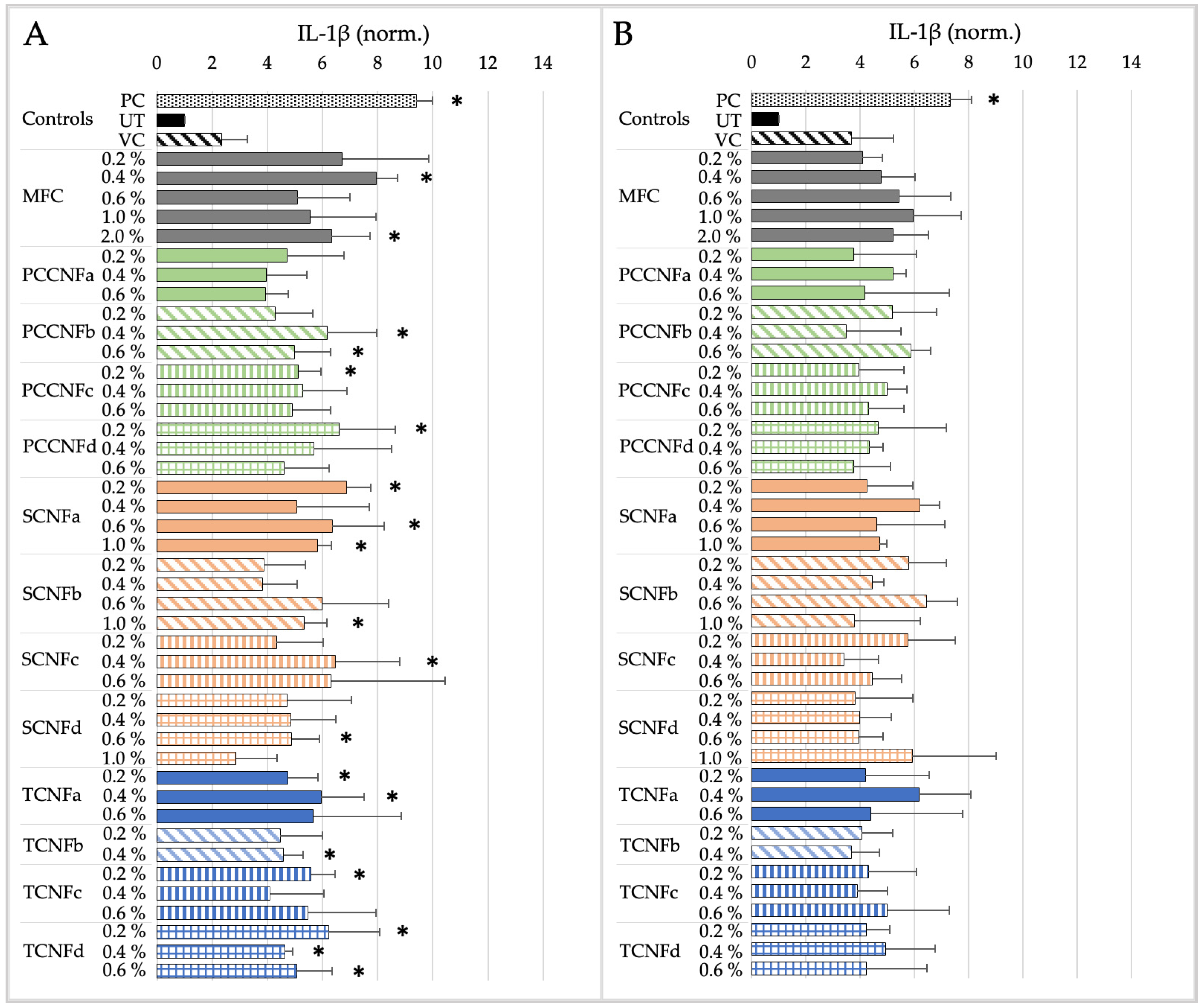

3.7.3. Dermal Hazard Evaluation

3.7.4. Summary: SbD Toolbox CN Hazard Assessment

- Following oral exposure, cellulose materials generally do not induce cytotoxicity or inflammation, or impact barrier integrity. The differences in chemistry, charge density, and morphology (i.e., length and width) between materials does not impact their oral cytotoxicity, inflammation, or barrier integrity. With a few noted exceptions, these data provide evidence that first-generation cellulose materials (i.e., MFC) and several second-generation CNs (TCNF, PCCNF, SCNF) can be grouped together for assessing these endpoints. Grouping is less supported for evaluating potential oxidative stress following oral exposure, given differences between surface chemistries and physical and chemical properties of materials.

- Following inhalation exposure, limited cytotoxicity is observed for all cellulose materials after 4 h of exposure. However, all materials induced pro-inflammatory markers at this timepoint. The results suggest that, for longer term inhalation exposures, grouping of first-generation cellulose materials (i.e., MFC) and second-generation CNs (TCNF, PCCNF, SCNF) is supported for inhalation hazard assessments. Given discrepant cytotoxicity and inflammation noted after 15 min of exposure, grouping is less supported for this timepoint.

- No dermal cytotoxicity was found. Pro-inflammatory impacts were similar across materials, with elevated proinflammatory markers after 15 min which subsided by 4 h of exposure. The grouping of MFC with second-generation CNs (PCCNFa-d, TCNFa-d, and SCNFa-d) is generally supported for evaluating potential cytotoxicity and pro-inflammation following dermal exposures.

3.8. Hazard Assessment: Literature Review

CN Composite Hazards

4. Discussion: Qualitative Health and Environmental Risk Characterization

4.1. Risks During Raw Material and Product Manufacturing Life-Cycle Stages

4.2. Risks During Product Application Life-Cycle Stage

4.3. Risks During Product Use Life-Cycle Stage

4.4. Risks During Re-Use and Recycling Life-Cycle Stages

4.5. Risks During Disposal Life-Cycle Stage

4.6. Risks to the Environment

5. Conclusions

- First and second-generation cellulose materials elicit similar cytotoxicity and pro-inflammatory responses following longer-term oral, dermal or inhalation exposures;

- At the doses and time points evaluated, cellulose materials behaved similarly and generally had limited cytotoxicity in oral, dermal and inhalation models. The materials also behaved similarly for inflammation endpoints, inducing limited pro-inflammatory mediators in the oral and dermal model, while significant pro-inflammatory mediator release was observed for all materials in the inhalation model;

- The similar biological responses of these materials provide supportive evidence that first-generation cellulose materials (i.e., MFC) and several second-generation CNs (TCNF, PCCNF, SCNF) can be grouped for oral, dermal, and inhalation hazard assessments.

- The exposure scenarios with the most direct and highest potential exposure to CNs were occupational activities during the product manufacturing and product application life-cycle stages. While these scenarios are the most controllable, no studies were identified evaluating potential hazards from low-dose, chronic exposure to CNs typical of the workplace. The screening level hazard assessment conducted with the SbD Toolbox highlighted potential inflammation from CN inhalation exposure, which was supported by studies evaluated in the literature which suggest CNs behave as poorly soluble, low-toxicity dusts with the potential to irritate the lung when inhaled;

- Once the CNs are incorporated into composite materials (e.g., water filtration membranes, food contact packaging) during the product application life-cycle stage, the primary exposure route is dermal and exposures are not likely to be to pristine CNs, but rather to CN composite particles. Our literature review found there is very limited data evaluating the migration or release of CNs from composites, and no studies were identified that evaluated the toxicity of CN composite particles. The exception is the use of CNs as a food additive, where direct consumer oral exposure is expected to occur. The screening level hazard assessment conducted with the SbD Toolbox suggests low oral toxicity from exposure to TCNF, PCCNF, and SCNF materials, and supported that these materials can be grouped with first-generation cellulose materials such as MFC, which have been demonstrated to be safe for oral consumption at high levels of the diet (e.g., up to 4 wt %) [9];

- There are limited risks to the environment from use of second-generation CNs in food and food contact packaging applications. These materials are biodegradable and therefor unlikely to accumulate in the environment; have limited potential to bioaccumulate; and have low ecotoxicity.

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CNs | cellulose nanomaterials |

| MFC | microfibrillated cellulose |

| CNFs | cellulose nanofibers or nanofibrils |

| SbD Toolbox | Safer-by-Design Toolbox |

| NM | nanomaterial |

| Nano LCRA | nanomaterial life-cycle risk assessment |

| CSs | case studies |

| TEMPO | 2,2,6,6-tetramethylpiperidin-1-oxyl radical |

| TCNF | TEMPO-oxidized carboxylated CNF |

| PC | periodate-chlorite |

| PCCNF | periodate-chlorite oxidized carboxylated CNF |

| SCNF | sulfated CNF |

| A549 cells | human epithelial lung cells |

| JAWSII | dendritic cells |

| FBS | Fetal Bovine Serum |

| cAMEM | Alpha minimum essential medium |

| VAG | Vilnius aerosol generator |

| HDFa | human dermal fibroblasts |

| HEKa | human epidermal keratinocytes |

| LDH | lactate dehydrogenase |

| IL | interleukin |

| NOAEL | No Observed Adverse Effect Level |

| LOAEL | Lowest Observed Adverse Effect Level |

| PPE | Personal Protective Equipment |

| OEA | occupational exposure assessments |

| NIOSH | National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health |

| CNCs | cellulose nanocrystals |

| NR/CC | natural rubber latex/cellulose (nano)crystals |

| PLA | polylactic acid |

| PHB | poly(3-hydroxybutyrate) |

| SAP | superabsorbent polymer |

| OECD | Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development |

| THP-1 cells | monocyte-derived macrophages |

| BALF | bronchoalveolar lavage fluid |

| SAA3 | Serum Amyloid A3 |

| MNPCEs | micronucleated bone marrow polychromatic erythrocytes |

| S-CNC | sulfated CNC |

| LC50 | Lethal Concentration 50% |

| EC50 | Half Maximal Effective Concentration |

| LD50 | Lethal Dose 50% |

References

- Endes, C.; Camarero-Espinosa, S.; Mueller, S.; Foster, E.J.; Petri-Fink, A.; Rothen-Rutishauser, B.; Weder, C.; Clift, M.J.D. A critical review of the current knowledge regarding the biological impact of nanocellulose. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2016, 14, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bombeck, P.L.; Hébert, J.; Richel, A. The use of enzymatic hydrolysis for the production of nanocellulose in an integrated forest biorefinery strategy (bibliographic synthesis). Biotechnol. Agron. Soc. Environ. 2016, 20, 94–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, R.J.; Schueneman, G.T.; Simonsen, J. Overview of Cellulose Nanomaterials, Their Capabilities and Applications. JOM 2016, 68, 2383–2394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chinga-Carrasco, G. Cellulose fibres, nanofibrils and microfibrils: The morphological sequence of MFC components from a plant physiology and fibre technology point of view. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 2011, 6, 417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalia, S.; Kaith, B.S.; Kaur, I. Pretreatments of natural fibers and their application as reinforcing material in polymer composites—A review. Polym. Eng. Sci. 2009, 49, 1253–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grishkewich, N.; Mohammed, N.; Tang, J.; Tam, K.C. Recent advances in the application of cellulose nanocrystals. Curr. Opin. Colloid Interface Sci. 2017, 29, 32–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shatkin, J.A.; Kim, B. Cellulose nanomaterials: Life cycle risk assessment, and environmental health and safety roadmap. Environ. Sci. Nano. 2015, 2, 477–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ede, J.D.; Ong, K.J.; Goergen, M.; Rudie, A.; Pomeroy-Carter, C.A.; Shatkin, J.A. Risk Analysis of Cellulose Nanomaterials by Inhalation: Current State of Science. Nanomaterials 2019, 9, 337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ong, K.J.; Ede, J.D.; Pomeroy-Carter, C.A.; Sayes, C.M.; Mulenos, M.R.; Shatkin, J.A. A 90-day dietary study with fibrillated cellulose in Sprague-Dawley rats. Toxicol. Rep. 2020, 7, 174–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ventura, C.; Pinto, F.; Lourenço, A.F.; Ferreira, P.J.T.; Louro, H.; Silva, M.J. On the toxicity of cellulose nanocrystals and nanofibrils in animal and cellular models. Cellulose 2020, 27, 5509–5544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vital, N.; Ventura, C.; Kranendonk, M.; Silva, M.J.; Louro, H. Toxicological Assessment of Cellulose Nanomaterials: Oral Exposure. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 3375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pradhan, S.H.; Mulenos, M.R.; Steele, L.R.; Gibb, M.; Ede, J.D.; Ong, K.J.; Shatkin, J.A.; Sayes, C.M. Physical, chemical, and toxicological characterization of fibrillated forms of cellulose using an in vitro gastrointestinal digestion and co-culture model. Toxicol. Res. 2020, 9, 290–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, Z.; Ngai, T. Recent Advances in Chemically Modified Cellulose and Its Derivatives for Food Packaging Applications: A Review. Polymers 2022, 14, 1533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Habibi, Y. Key advances in the chemical modification of nanocelluloses. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2014, 43, 1519–1542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kangas, H.; Pitkänen, M. Environmental, Health & Safety (EHS) aspects of cellulose nanomaterials (CN) and CN-based products. Nord. Pulp Pap. Res. J. 2016, 31, 179–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpenter, A.W.; De Lannoy, C.F.; Wiesner, M.R. Cellulose Nanomaterials in Water Treatment Technologies. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2015, 49, 5277–5287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rashki, S.; Shakour, N.; Yousefi, Z.; Rezaei, M.; Homayoonfal, M.; Khabazian, E.; Atyabi, F.; Aslanbeigi, F.; Lapavandani, R.S.; Mazaheri, S.; et al. Cellulose-Based Nanofibril Composite Materials as a New Approach to Fight Bacterial Infections. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2021, 9, 732461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Ge, H.; Xu, M.; Cao, J.; Dai, Y. Physicochemical properties, antioxidant and antibacterial activities of dialdehyde microcrystalline cellulose. Cellulose 2017, 24, 2287–2298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chng, E.L.K.; Pumera, M. The Toxicity of Graphene Oxides: Dependence on the Oxidative Methods Used. Chemistry 2013, 19, 8227–8235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, K.; Li, Y.; Tan, X.; Peng, R.; Liu, Z. Behavior and Toxicity of Graphene and Its Functionalized Derivatives in Biological Systems. Small 2013, 9, 1492–1503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Chemicals Agency, Appendix for Nanoforms Applicable to the Guidance on QSARs and Grouping of Chemicals: Guidance on Information Requirements and Chemical Safety Assessment, European Chemicals Agency. 2019. Available online: https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2823/273911 (accessed on 22 January 2025).

- Yetisen, A.K.; Qu, H.; Manbachi, A.; Butt, H.; Dokmeci, M.R.; Hinestroza, J.P.; Skorobogatiy, M.; Khademhosseini, A.; Yun, S.H. Nanotechnology in Textiles. ACS Nano 2016, 10, 3042–3068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ede, J.D.; Diges, A.S.; Zhang, Y.; Shatkin, J.A. Life-cycle risk assessment of graphene-enabled textiles in fire protection gear. NanoImpact 2024, 33, 100488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charlton-Sevcik, A.K.; Collom, C.; Liu, J.Y.; Hsieh, Y.L.; Stark, N.; Ede, J.D.; Shatkin, J.A.; Sayes, C.M. The impact of surface functionalization of cellulose following simulated digestion and gastrointestinal cell-based model exposure. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 271, 132603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, M.; Ede, J.D.; Sayes, C.M.; Shatkin, J.A.; Stark, N.; Hsieh, Y.L. Regioselectively Carboxylated Cellulose Nanofibril Models from Dissolving Pulp: C6 via TEMPO Oxidation and C2,C3 via Periodate–Chlorite Oxidation. Nanomaterials 2024, 14, 479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pingrey, B.; Ede, J.D.; Sayes, C.M.; Shatkin, J.A.; Stark, N.; Hsieh, Y.L. Aqueous exfoliation and dispersion of monolayer and bilayer graphene from graphite using sulfated cellulose nanofibrils. RSC Adv. 2024, 14, 9860–9868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, T.; Amadei, C.A.; Gou, N.; Lin, Y.; Lan, J.; Vecitis, C.D.; Gu, A.Z. Toxicity of single-walled carbon nanotubes (SWCNTs): Effect of lengths, functional groups and electronic structures revealed by a quantitative toxicogenomics assay. Environ. Sci. Nano. 2020, 7, 1348–1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NIOSH. Occupational Exposure Sampling for Engineered Nanomaterials. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. 2022. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/docs/2022-153/ (accessed on 22 January 2025).

- Martinez, K.F.; Eastlake, A.; Rudie, A.; Geraci, C. Chapter 1.2 Health Safety and Environment: Occupational Exposure Characterization during the Manufacture of Cellulose Nanomaterials. In Production and Applications of Cellulose Nanomaterials; Postek, M.T., Moon, R.J., Rudie, A.W., Bilodeau, M.A., Eds.; TAPPI PRESS: Peachtree Corners, GA, USA, 2013; ISBN 978-1-59510-224-9. [Google Scholar]

- Old, L.; Methner, M.M. Engineering Case Reports: Effectiveness of Local Exhaust Ventilation (LEV) in Controlling Engineered Nanomaterial Emissions During Reactor Cleanout Operations. J. Occup. Environ. Hyg. 2008, 5, D63–D69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ogura, I.; Kotake, M.; Kuboyama, T.; Kajihara, H. Measurements of cellulose nanofiber emissions and potential exposures at a production facility. NanoImpact 2020, 20, 100273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vartiainen, J.; Pöhler, T.; Sirola, K.; Pylkkänen, L.; Alenius, H.; Hokkinen, J.; Tapper, U.; Lahtinen, P.; Kapanen, A.; Putkisto, K.; et al. Health and environmental safety aspects of friction grinding and spray drying of microfibrillated cellulose. Cellulose 2011, 18, 775–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, B.; Berry, R.; Goguen, R. Chapter 10—Commercialization of Cellulose Nanocrystal (NCCTM) Production: A Business Case Focusing on the Importance of Proactive EHS Management. In Nanotechnology Environmental Health and Safety: Risks, Regulation, and Management (Micro and Nano Technologies), 2nd ed.; Hull, M.S., Bowman, D., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2014; ISBN 978-1-4557-3188-6. [Google Scholar]

- Gong, X.; Liu, T.; Zhang, H.; Liu, Y.; Boluk, Y. Release of Cellulose Nanocrystal Particles from Natural Rubber Latex Composites into Immersed Aqueous Media. ACS Appl. Bio Mater. 2021, 4, 1413–1423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fortunati, E.; Peltzer, M.; Armentano, I.; Jiménez, A.; Kenny, J.M. Combined effects of cellulose nanocrystals and silver nanoparticles on the barrier and migration properties of PLA nano-biocomposites. J. Food Eng. 2013, 118, 117–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhar, P.; Tarafder, D.; Kumar, A.; Katiyar, V. Effect of cellulose nanocrystal polymorphs on mechanical, barrier and thermal properties of poly(lactic acid) based bionanocomposites. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 60426–60440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, L.; Ledesma, R.M.B.; Tanner, J.; Garnier, G. Effect of crosslinking on nanocellulose superabsorbent biodegradability. Carbohydr. Polym. Technol. Appl. 2022, 3, 100199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barajas-Ledesma, R.M.; Wong, V.N.L.; Little, K.; Patti, A.F.; Garnier, G. Carboxylated nanocellulose superabsorbent: Biodegradation and soil water retention properties. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2022, 139, 51495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kümmerer, K.; Menz, J.; Schubert, T.; Thielemans, W. Biodegradability of organic nanoparticles in the aqueous environment. Chemosphere 2011, 82, 1387–1392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aimonen, K.; Hartikainen, M.; Imani, M.; Suhonen, S.; Vales, G.; Moreno, C.; Saarelainen, H.; Siivola, K.; Vanhala, E.; Wolff, H.; et al. Effect of Surface Modification on the Pulmonary and Systemic Toxicity of Cellulose Nanofibrils. Biomacromolecules 2022, 23, 2752–2766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Catalán, J.; Rydman, E.; Aimonen, K.; Hannukainen, K.S.; Suhonen, S.; Vanhala, E.; Moreno, C.; Meyer, V.; da Silva Perez, D.; Sneck, A. Genotoxic and inflammatory effects of nanofibrillated cellulose in murine lungs. Mutagenesis 2017, 1, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilves, M.; Vilske, S.; Aimonen, K.; Lindberg, H.K.; Pesonen, S.; Wedin, I.; Nuopponen, M.; Vanhala, E.; Højgaard, C.; Winther, J.R. Nanofibrillated cellulose causes acute pulmonary inflammation that subsides within a month. Nanotoxicology 2018, 12, 729–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hadrup, N.; Knudsen, K.B.; Berthing, T.; Wolff, H.; Bengtson, S.; Kofoed, C.; Espersen, R.; Højgaard, C.; Winther, J.R.; Willemoës, M.; et al. Pulmonary effects of nanofibrillated celluloses in mice suggest that carboxylation lowers the inflammatory and acute phase responses. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2019, 66, 116–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujita, K.; Obara, S.; Maru, J.; Endoh, S. Genotoxicity assessment of cellulose nanofibrils using a standard battery of in vitro and in vivo assays. Toxicol. Rep. 2022, 9, 68–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ventura, C.; Lourenço, A.F.; Sousa-Uva, A.; Ferreira, P.J.T.; Silva, M.J. Evaluating the genotoxicity of cellulose nanofibrils in a co-culture of human lung epithelial cells and monocyte-derived macrophages. Toxicol. Lett. 2018, 291, 173–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimotoyodome, A.; Suzuki, J.; Kumamoto, Y.; Hase, T.; Isogai, A. Regulation of Postprandial Blood Metabolic Variables by TEMPO-Oxidized Cellulose Nanofibers. Biomacromolecules 2011, 12, 3812–3818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordli, H.R.; Chinga-Carrasco, G.; Rokstad, A.M.; Pukstad, B. Producing ultrapure wood cellulose nanofibrils and evaluating the cytotoxicity using human skin cells. Carbohydr. Polym. 2016, 150, 65–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fujita, K.; Obara, S.; Maru, J.; Endoh, S. Pulmonary inflammation following intratracheal instillation of cellulose nanofibrils in rats: Comparison with multi-walled carbon nanotubes. Cellulose 2021, 11, 7143–7164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tai, R.; Ogura, I.; Okazaki, T.; Iizumi, Y.; Mano, H. Acute toxicity tests of TEMPO-oxidized cellulose nanofiber using Daphnia magna and Oryzias latipes. Cellulose 2024, 31, 2207–2220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tai, R.; Ogura, I.; Okazaki, T.; Iizumi, Y.; Mano, H. Algal growth inhibition test with TEMPO-oxidized cellulose nanofibers. NanoImpact 2024, 34, 100504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rusconi, T.; Riva, L.; Punta, C.; Solé, M.; Corsi, I. Environmental safety of nanocellulose: An acute in vivo study with marine mussels Mytilus galloprovincialis. Environ. Sci. Nano 2024, 11, 61–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esposito, M.C.; Russo, G.L.; Riva, L.; Punta, C.; Corsi, I.; Tosti, E.; Gallo, A. Nanostructured cellulose sponge engineered for marine environmental remediation: Eco-safety assessment of its leachate on sea urchin reproduction (Part A). Environ. Pollut. 2023, 334, 122169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harper, B.J.; Clendaniel, A.; Sinche, F.; Way, D.; Hughes, M.; Schardt, J.; Simonsen, J.; Stefaniak, A.B.; Harper, S.L. Impacts of chemical modification on the toxicity of diverse nanocellulose materials to developing zebrafish. Cellulose 2016, 23, 1763–1775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yanamala, N.; Farcas, M.T.; Hatfield, M.K.; Kisin, E.R.; Kagan, V.E.; Geraci, C.L.; Shvedova, A.A. In Vivo Evaluation of the Pulmonary Toxicity of Cellulose Nanocrystals: A Renewable and Sustainable Nanomaterial of the Future. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2014, 2, 1691–1698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Endes, C.; Schmid, O.; Kinnear, C.; Mueller, S.; Camarero-Espinosa, S.; Vanhecke, D.; Foster, E.J.; Petri-Fink, A.; Rothen-Rutishauser, B.; Weder, C.; et al. An in vitro testing strategy towards mimicking the inhalation of high aspect ratio nanoparticles. Part. Fibre Toxicol. 2014, 11, 1691–1698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clift, M.J.D.; Foster, E.J.; Vanhecke, D.; Studer, D.; Wick, P.; Gehr, P.; Rothen-Rutishauser, B.; Weder, C. Investigating the Interaction of Cellulose Nanofibers Derived from Cotton with a Sophisticated 3D Human Lung Cell Coculture. Biomacromolecules 2011, 12, 3666–3673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ede, J.D.; Ong, K.J.; Mulenos, M.R.; Pradhan, S.; Gibb, M.; Sayes, C.M.; Shatkin, J.A. Physical, chemical, and toxicological characterization of sulfated cellulose nanocrystals for food-related applications using in vivo and in vitro strategies. Toxicol. Res. 2020, 9, 808–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shvedova, A.A.; Kisin, E.R.; Yanamala, N.; Farcas, M.T.; Menas, A.L.; Williams, A.; Fournier, P.M.; Reynolds, J.S.; Gutkin, D.W.; Star, A.; et al. Gender differences in murine pulmonary responses elicited by cellulose nanocrystals. Part. Fibre Toxicol. 2015, 13, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovacs, T.; Naish, V.; O’Connor, B.; Blaise, C.; Gagné, F.; Hall, L.; Trudeau, V.; Martel, P. An ecotoxicological characterization of nanocrystalline cellulose (NCC). Nanotoxicology 2010, 4, 255–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wohlleben, W.; Brill, S.; Meier, M.W.; Mertler, M.; Cox, G.; Hirth, S.; von Vacano, B.; Strauss, V.; Treumann, S.; Wiench, K. On the Lifecycle of Nanocomposites: Comparing Released Fragments and their In-Vivo Hazards from Three Release Mechanisms and Four Nanocomposites. Small 2011, 7, 2384–2395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bishop, L.; Cena, L.; Orandle, M.; Yanamala, N.; Dahm, M.M.; Birch, M.E.; Evans, D.E.; Kodali, V.K.; Eye, T.; Battelli, L.; et al. In Vivo Toxicity Assessment of Occupational Components of the Carbon Nanotube Life Cycle To Provide Context to Potential Health Effects. ACS Nano 2017, 11, 8849–8863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Reagent, Concentration (mmol/g), Time (min) | BT (min) | Length (nm) | Width (nm) | Charge (mmol/g) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PCCNFa | NaIO4, 3.08, 4; NaClO2, 6.16, 30 | 30 | 452 ± 162 | 5.9 ± 1.6 | 0.72 |

| PCCNFb | NaIO4, 3.08, 4; NaClO2, 6.16, 9 h | 30 | 533 ± 275 | 5.7 ± 1.6 | 0.82 |

| PCCNFc | NaIO4, 3.08, 4; NaClO2, 6.16, 12 h | 30 | 381 ± 150 | 5.5 ± 1.6 | 0.91 |

| PCCNFd | NaIO4, 4.62, 4; NaClO2, 6.16, 6 h | 30 | 344 ± 170 | 5.6 ± 1.7 | 1.04 |

| TCNFa | NaClO, 3, 30 | 30 | 551 ± 200 | 6.5 ± 2.2 | 1.1 |

| TCNFb | NaClO, 5, 50 | 10 | 486 ± 174 | 6.1 ± 1.6 | 1.42 |

| TCNFc | NaClO, 5, 60 | 30 | 530 ± 145 | 4.6 ± 1.6 | 1.42 |

| TCNFd | NaClO, 8, 80 | 30 | 486 ± 206 | 4.9 ± 2.0 | 1.48 |

| SCNFa | HSO3Cl, 1, 30 | 30 | 693 ± 330 | 3.2 ± 0.9 | 1.49 |

| SCNFb | HSO3Cl, 1.25, 45 | 30 | 577 ± 294 | 4.0 ± 1.0 | 1.84 |

| SCNFc | HSO3Cl, 1.5, 60 | 5 | 501 ± 295 | 3.2 ± 0.7 | 2.23 |

| SCNFd | HSO3Cl, 1.5, 60 | 30 | 365 ± 194 | NA | 2.23 |

| Form | Functional Group | Regioselectivity | CN Form | Reaction | Reagent |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chemically Unmodified Cellulose Materials | |||||

| MFC | Cellulose-OH | NA | MFC | None | None |

| Chemically Modified CNs | |||||

| Sulfated | Cellulose-OSO3 | None | SCNF | Sulfation | Chlorosulfonic Acid |

| Carboxylated (TEMPO) | Cellulose-COOH | C6 | TCNF | Oxidation | TEMPO |

| Carboxylated (PC) | Cellulose-COOH | C2 and C3 | PCCNF | Oxidation | Periodate/Chlorite (P/C) |

| CS Applications | Water Filtration | Food Contact | Food Additive | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CS1 | CS2.1 | CS2.2 | CS2.3 | CS3 | |

| Scenario | Water Filtration Membrane | Food Packaging Film | Food Packaging Coating | Food Packaging Additive | Food Additive |

| Manufacture and use of a CNF membrane for water filtration. | Manufacture and use of a CNF food packaging film. | Manufacture and use of a CNF barrier coating applied to food contact packaging. | Manufacture and use of CNF as a food packaging additive. | Manufacture and use of CNF as a food additive. | |

| CNF Chemistries | TCNF and PCCNF (Carboxylated) | TCNF and PCCNF (Carboxylated) | SCNF (Sulfated) | SCNF (Sulfated) | TCNF and PCCNF (Carboxylated) |

| All Life-Cycle Stages |

| ||||

| Raw Material |

| ||||

| Product Manufacturing |

| ||||

|

| Follows conventional sulfation steps for CN. |

| ||

| Product Application |

| ||||

|

|

|

|

| |

| Product Use |

|

|

|

|

|

| Re-Use/ Recycling |

| ||||

|

|

|

|

| |

| Disposal |

| ||||

| Directness of Exposure | Magnitude | Likelihood | Frequency | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low (1) | Covalently bound CN in substrate | Exposure to an article where one component is <1% CN | Direct contact mitigated | Infrequent—exposure possible < 10 times per year |

| Medium (2) | CN potentially releasable from substrate | Exposure to a material 1% < CN < 10% | Unintentional—exposure possible based on activity | Incidental—use 10–50 times per year |

| High (3) | Dried CN in powder form | Exposure to a material >10% CN | Intentional—repeat exposure during normal use | Regular—greater than 50 times per year |

| NOAEL/LOAEL Value | Cytotoxicity | Inflammation | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 15 min | 4 h | 15 min | 4 h | |

| MFC | NOAEL > 2% | NOAEL > 2% | NOAEL > 2% | NOAEL > 2% |

| PCCNFa | NOAEL > 0.6% | NOAEL > 0.6% | NOAEL > 0.6% | NOAEL > 0.6% |

| PCCNFb | NOAEL > 0.6% | NOAEL > 0.6% | LOAEL = 0.2% | NOAEL > 0.6% |

| PCCNFc | NOAEL > 0.6% | NOAEL > 0.6% | NOAEL > 0.6% | NOAEL > 0.6% |

| PCCNFd | NOAEL > 0.6% | NOAEL > 0.6% | NOAEL > 0.6% | NOAEL > 0.6% |

| TCNFa | NOAEL > 0.6% | NOAEL > 0.6% | NOAEL > 0.6% | NOAEL > 0.6% |

| TCNFb | NOAEL > 0.4% | NOAEL > 0.4% | NOAEL > 0.4% | NOAEL > 0.4% |

| TCNFc | NOAEL > 0.6% | NOAEL > 0.6% | NOAEL > 0.6% | NOAEL > 0.6% |

| TCNFd | NOAEL > 0.6% | NOAEL > 0.6% | NOAEL > 0.6% | NOAEL > 0.6% |

| SCNFa | NOAEL > 1% | NOAEL > 1% | NOAEL > 1% | NOAEL > 1% |

| SCNFb | NOAEL > 1% | NOAEL > 1% | NOAEL > 1% | NOAEL > 1% |

| SCNFc | NOAEL > 0.6% | NOAEL > 0.6% | NOAEL > 0.6% | NOAEL > 0.6% |

| SCNFd | NOAEL > 1% | NOAEL > 1% | NOAEL > 1% | NOAEL > 1% |

| NOAEL/LOAEL Value | Oxidative Stress | Barrier Integrity | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 15 min | 4 h | 8 Days | |

| MFC | NOAEL > 2% | NOAEL > 2% | NOAEL > 2% |

| PCCNFa | NOAEL > 0.6% | NOAEL > 0.6% | NOAEL > 0.6% |

| PCCNFb | NOAEL > 0.6% | NOAEL > 0.6% | NOAEL > 0.6% |

| PCCNFc | NOAEL > 0.6% | NOAEL > 0.6% | NOAEL > 0.6% |

| PCCNFd | NOAEL > 0.6% | NOAEL > 0.6% | NOAEL > 0.6% |

| TCNFa | LOAEL = 0.4% | NOAEL > 0.6% | LOAEL = 0.6% |

| TCNFb | NOAEL > 0.4% | NOAEL > 0.4% | NOAEL > 0.4% |

| TCNFc | NOAEL > 0.6% | NOAEL > 0.6% | NOAEL > 0.6% |

| TCNFd | NOAEL > 0.6% | NOAEL > 0.6% | NOAEL > 0.6% |

| SCNFa | LOAEL = 0.2% | NOAEL > 1% | NOAEL > 1% |

| SCNFb | NOAEL > 1% | NOAEL > 1% | NOAEL > 1% |

| SCNFc | NOAEL > 0.6% | LOAEL = 0.4% | NOAEL > 1% |

| SCNFd | NOAEL > 1% | LOAEL = 0.2% | NOAEL > 1% |

| NOAEL/LOAEL Value | Cytotoxicity | Inflammation | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 15 min | 4 h | 15 min | 4 h | |

| MFC | NOAEL > 2% | NOAEL > 2% | LOAEL = 1% | LOAEL = 0.4% |

| PCCNFa | LOAEL = 0.6% | LOAEL = 0.6% | LOAEL = 0.2% | LOAEL = 0.2% |

| PCCNFb | NOAEL > 0.6% | NOAEL > 0.6% | NOAEL > 0.6% | LOAEL = 0.2% |

| PCCNFc | LOAEL = 0.6% | NOAEL > 0.6% | NOAEL > 0.6% | LOAEL = 0.2% |

| PCCNFd | NOAEL > 0.6% | NOAEL > 0.6% | LOAEL = 0.6% | LOAEL = 0.2% |

| TCNFa | NOAEL > 1% | NOAEL > 0.6% | LOAEL = 0.6% | LOAEL = 0.2% |

| TCNFb | NOAEL > 0.4% | NOAEL > 0.4% | LOAEL = 0.2% | LOAEL = 0.2% |

| TCNFc | NOAEL > 1% | NOAEL > 0.6% | LOAEL = 0.4% | LOAEL = 0.2% |

| TCNFd | NOAEL > 1% | NOAEL > 0.6% | NOAEL > 0.6% | LOAEL = 0.2% |

| SCNFa | LOAEL = 1% | NOAEL > 1% | NOAEL > 1% | LOAEL = 0.4% |

| SCNFb | LOAEL = 1% | NOAEL > 1% | NOAEL > 1% | LOAEL = 0.4% |

| SCNFc | NOAEL > 0.6% | NOAEL > 0.6% | NOAEL > 0.6% | LOAEL = 0.4% |

| SCNFd | NOAEL > 1% | NOAEL > 1% | LOAEL = 0.2% | LOAEL = 0.2% |

| NOAEL/ LOAELValue | Cytotoxicity | Inflammation | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 15 min | 4 h | 15 min | 4 h | |

| MFC | NOAEL > 2% | NOAEL > 2% | LOAEL = 0.4% | NOAEL > 2% |

| PCCNFa | NOAEL > 0.6% | NOAEL > 0.6% | NOAEL > 0.6% | NOAEL > 0.6% |

| PCCNFb | NOAEL > 0.6% | NOAEL > 0.6% | LOAEL = 0.4% | NOAEL > 0.6% |

| PCCNFc | NOAEL > 0.6% | NOAEL > 0.6% | LOAEL = 0.2% | NOAEL > 0.6% |

| PCCNFd | NOAEL > 0.6% | NOAEL > 0.6% | LOAEL = 0.2% | NOAEL > 0.6% |

| TCNFa | NOAEL > 0.6% | NOAEL > 0.6% | LOAEL = 0.2% | NOAEL > 0.6% |

| TCNFb | NOAEL > 0.4% | NOAEL > 0.4% | LOAEL = 0.4% | NOAEL > 0.4% |

| TCNFc | NOAEL > 0.6% | NOAEL > 0.6% | LOAEL = 0.2% | NOAEL > 0.6% |

| TCNFd | NOAEL > 0.6% | NOAEL > 0.6% | LOAEL = 0.2% | NOAEL > 0.6% |

| SCNFa | NOAEL > 1% | NOAEL > 1% | LOAEL = 0.2% | NOAEL > 1% |

| SCNFb | NOAEL > 1% | NOAEL > 1% | LOAEL = 1% | NOAEL > 1% |

| SCNFc | NOAEL > 0.6% | NOAEL > 0.6% | LOAEL = 0.4% | NOAEL > 0.6% |

| SCNFd | NOAEL > 1% | NOAEL > 1% | LOAEL = 0.6% | NOAEL > 1% |

| Form | Endpoint and Model | Result | Benchmark | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Human Health—Acute Toxicity | ||||

| (i) Inhalation | ||||

| TCNF | Female C57BL/6 mice; 1-, 28-, and 90-day toxicity | TCNF at the dose of 56 µg/mouse/aspiration significantly increased the neutrophil counts in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) on day 1. | 1-day LOAEL for neutrophil influx: 50 µg/mouse/aspiration | [40] |

| TCNF | Female C57BL/6 mice; 24 h (OECD 474, OECD 489) | TCNF significantly induced DNA damage in lung cells, increased the recruitment of inflammatory cells to the lungs, and increased mRNA expression of tumor necrosis factor α, IL-1β, IL-6, and chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 5 in a dose-dependent manner, but had no effects on the bone marrow micronucleus. | [41] | |

| Carboxylated CNF | Female C57BL/6 mice; 24 h | Carboxylated CNF at 40 µg/mouse triggered influx of neutrophils into BAL and elevated the mRNA expression of IL-6 and IL-13 in the lung tissue 24 h after treatment, but had no effects on eosinophils, IL-1β, and Tumor Necrosis Factor (TNF). | 24-h LOAEL for IL-6 and IL-13 mRNA: 40 µg/mouse | [42] |

| Carboxylated CNF | Female C57BL/6 mice; 24 h | Exposure to 0.9 mg/kg bw/day of CNF at day 1 post-exposure significantly induced total neutrophil influx into BAL fluid and systemic Serum Amyloid A3 (SAA3) levels | 24-h NOAEL for pulmonary inflammation: 0.3 mg/kg bw/day | [43] |

| TCNF | Sprague-Dawley rats; 2 days (OECD 474) | No difference between the proportion of micronucleated bone marrow polychromatic erythrocytes (MNPCEs) in bone marrow from exposure to TCNF compared to the negative control group | NOAEL for MNPCEs: 1.0 mg/kg | [44] |

| TCNF | Co-culture of A549 and monocyte-derived macrophage (THP-1) cells; 24 or 48 h (OECD 487) | No proinflammatory cytokine IL-1β was detected in the co-culture suggesting no immunotoxicity. TCNF treatment did not induce sizable levels of DNA damage in A549 cells, but it led to micronuclei formation at 1.5 and 3 μg/cm2 | NOAEL for immunotoxicity and DNA damage: 25 µg/cm2 | [45] |

| (ii) Oral | ||||

| TCNF | Male C57BL/6J mice; up to 2 h | TCNF (1.2 mmol/g carboxyl content and 120 aspect ratio) exposure significantly reduced the postprandial blood glucose, plasma insulin, GIP, and triglyceride concentrations. | [46] | |

| (iii) Dermal | ||||

| TCNF | HEKa and HDFa; up to 24 h (ISO 10993-5) | TCNF had no effects on cytotoxicity and cytokine induction up to 50 µg/mL but slightly decreased metabolic activity. | 24-h NOAEL for cytotoxicity and cytokine induction: 50 µg/mL | [47] |

| (iv) Eye | ||||

| No data available | ||||

| 2. Human Health—Subchronic and Chronic Toxicity | ||||

| (i) Inhalation | ||||

| TCNF | Female C57BL/6 mice; 1-, 28-, and 90-day toxicity | TCNF significantly increased neutrophil counts in BAL on day 28 (80 and 200 µg/mouse/aspiration) and day 90 (200 µg/mouse/aspiration). TCNF at doses of 14, 28, and 56 µg/mouse/aspiration significantly increased DNA damage in BAL at 90 days. | 90-day LOAEL for neutrophil influx: 50 µg/mouse/aspiration. 28-day LOAEL for neutrophil influx: 28 µg/mouse/aspiration. 90-day LOAEL for DNA damage: 14 µg/mouse/aspiration. | [40] |

| Carboxylated CNF | Female C57BL/6 mice; 28 days | Carboxylated CNF induced modest immune responses after 28 days, indicated by a slight increase in the number of neutrophils and lymphocytes in lung tissue. However, the effects were markedly attenuated as compared with the ones after 24 h. | [42] | |

| Carboxylated CNF | Female C57BL/6 mice; 28 days | Exposure to 0.3 mg/kg bw/day of CNF at day 28 post-exposure significantly induced total neutrophil influx into BAL fluid, but had no effects on systemic SAA3 levels. | 28-day NOAEL for SAA: 0.9 mg/kg bw/day | [43] |

| TCNF | Male Sprague-Dawley rats; 90 days | BALF analysis, histopathological examination, and a comprehensive gene expression analysis confirmed acute inflammation following the instillation of TCNFs. | [48] | |

| 3. Ecotoxicity | ||||

| TCNF | Daphnia magna: 24, 48, and 96 h (OECD TG 202) | No acute toxicity was observed at any given concentrations. | LC50 > 100 mg/L EC50 > 100 mg/L | [49] |

| Oryzias latipes; 24, 48, and 96 h (OECD TG 203) | No acute toxicity was observed at any given concentrations. | LC50 > 100 mg/L EC50 > 100 mg/L | ||

| TCNF | Raphidocelis subcapitata; 72 h (OECD 201) | No growth inhibition was observed at all concentrations tested (up to 100 mg/L). | 72 h-EC50 of growth inhibition > 100 mg/L | [50] |

| TCNF | Mytilus galloprovincialis; 48 and 96 h | No effects on oxidative stress or biotransformation were observed in the digestive glands and gills. The destabilization of lysosomal membranes of hemocytes, the inhibition of P-glycoprotein efflux activities in the gills and the inhibition of cholinergic enzymes (ASCh–ChE) activities in hemocytes, gills, and digestive glands were observed. | [51] | |

| TCNF | Paracentrotus lividus and Arbacia lixula; 48 h | TCNF leachate exposure inhibited sea urchin embryo development, decreased sperm fertilizing capability and egg fertilization competence, and significantly reduced sperm motility. In A. lixula spermatozoa, a significant increase in the intracellular hydrogen peroxide level has been recorded. In P. lividus eggs, the MMP values significantly increased. | [52] | |

| TCNF | Zebrafish embryo; 5 days | No mortality or effects on the incidence rate of pericardial and yolk sac edema were observed from TCNF exposure at a concentration of 250 mg/L. | 5-day LC50 > 100 mg/L. 5-day EC50 of pericardial edema > 250 mg/L. 5-day EC50 of yolk sac edema > 250 mg/L. | [53] |

| Form | Endpoint and Model | Result | Benchmark | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Human Health—Acute Toxicity | ||||

| (i) Inhalation | ||||

| S-CNC | Rats; 4 h (OECD 403) | No mortality, gross toxicity, adverse effects, or abnormalities in rats exposed to 0.26 mg/L of S-CNC for 4 h was observed. | NOAEL: 0.26 mg/L | [33] |

| CNC | Female C57BL/6 mice; 24 h | Exposure to CNC led to an innate inflammatory response, as evidenced by an increase in the number of leukocytes and eosinophils recovered by BAL. Exposure to CNC induced lung damage (LDH) and oxidative stress (formation of protein carbonyls and elevation of 40 hydroxynonenal). | [54] | |

| S-CNC | Triple cell co-culture model of the human epithelial airway barrier; 24 h | No significant cytotoxicity, induction of oxidative stress, or pro-inflammatory response at any concentrations was observed. | NOAEL: 1.57 µg/cm2 | [55] |

| S-CNC | 3D triple cell coculture model of THP-1, JAWSII, and 16 Human Bronchial Epithelial Cells, Clone 14o (16HBE14o-); 24 h | Apical cytotoxicity was observed at concentrations of 15 and 30 mg/L, but no basolateral cytotoxicity at any dose examined. A small elevation of pro-inflammatory chemokine at the highest dose tested (30 mg/L). | [56] | |

| (ii) Oral | ||||

| S-CNC | Sprague-Dawley rats; 7 and 14 days (OECD 407) | No adverse effects on cytotoxicity, metabolic activity, membrane permeability, oxidative stress, and proinflammatory responses from oral CNC exposure in rats up to 4% of the diet. | NOAEL (male) > 2085.3 mg/kg/day. NOAEL (female) > 2682.8 mg/kg/day | [57] |

| S-CNC | Rats; 14 days (OECD 425) | No effects were observed at the highest concentration tested. Not considered to present a significant hazard if swallowed. | 14-day, one-time dose LD50 > 2000 mg/kg | [33] |

| (iii) Dermal | ||||

| S-CNC | Rabbits; 4 h (OECD 404) | No corrosive effects were observed from a single dose of S-CNC (0.5 g) for 4 h on the skin of an albino rabbit. | [33] | |

| S-CNC | Guinea pigs; Acute (OECD 406) | S-CNC was found to be non-sensitizing at a single dose of 1.1 mg/mL (intradermal) and 103 mg/mL (topical induction and challenges phase). | ||

| S-CNC | Mice; 6 days (OECD 429) | S-CNC was not considered to be a contact dermal sensitizer at concentrations of <10.7%. | ||

| (iv) Eye | ||||

| No data available | ||||

| 2. Human Health—Subchronic and Chronic Toxicity | ||||

| (i) Inhalation | ||||

| S-CNC | Male and female C57BL/6 mice; 3 weeks | Exposure resulted in pulmonary inflammation and damage, elevated oxidative stress, increased TGF-β and collagen levels in lung, and impaired pulmonary functions. | [58] | |

| (ii) Oral | ||||

| S-CNC | Rats; 28 days (OECD 407) | No toxicity was observed at any dose. All parameters (neurological, body weight, weight gain, and food consumption) were not different from control. | 28-day NOAEL > 2000 mg/kg/day | [33] |

| S-CNC | Sprague-Dawley rats; 90 days (OECD 408) | No adverse effects on cytotoxicity, metabolic activity, membrane permeability, oxidative stress, and proinflammatory responses from oral CNC exposure in rats up to 4% of the diet. | NOAEL (male) > 2085.3 mg/kg/day. NOAEL (female) > 2682.8 mg/kg/day | [57] |

| (iii) Dermal | ||||

| No data available | ||||

| (iv) Eye | ||||

| No data available | ||||

| 3. Ecotoxicity | ||||

| S-CNC | D. magna; 48 h | 48-h LC50 > 1 g/L | [59] | |

| Ceriodaphnia dubia; 48 h | 48-h LC50 > 1 g/L | |||

| Rainbow trout; 96 h | 96-h LC50 > 1 g/L | |||

| Fathead minnow; 10 days | Exposure to 0.3–0.24 g/L of S-CNC for 10 days had no effects on the cumulative egg production. S-CNC at 0.48 g/L significantly reduced egg production. | 10-day IC50 of reproduction: 0.29 g/L | ||

| Zebrafish embryo; 96 h | 96-h LC50 > 6 g/L 96-h IC50 of delayed hatching > 6 g/L | |||

| Rainbow trout hepatocytes; 48 h | 48-h EC50 of cell viability: 245 mg/L. 48-h EC50 of total sugars: 23 mg/L. 48-h EC50 of lipid peroxidation: 434 mg/L. 48-h EC50 of available zinc > 2000 mg/L. 48-h EC50 of heat shock proteins > 2000 mg/L. 48-h EC50 of DNA strand break > 2000 mg/L | |||

| Vibrio fischeri; 15 min | 15-min IC25 of luminescence > 10 g/L | |||

| Pseudokirchneriella subcapitata; 72 h | 72-h IC25 of cell growth > 2.5 g/L | |||

| Thamnocephalus platyurus; 24 h | 24-h LC50: 13.2 g/L | |||

| Hydra attenuate; 96 h | 96-h LC50: 14.22 g/L (batch 4 of CNC at pH 6.8). 96-h LC50 > 6.8 g/L (batch 5b of CNC at pH 6.4). 96-h EC50 of morphological anomalies: 2.6 g/L (batch 4 of CNC at pH 6.8). 96-h EC50 of morphological anomalies > 6.8 g/L (batch 5b of CNC at pH 6.4) | |||

| S-CNC | Zebrafish embryo; 5 days | No significant sublethal impacts of S-CNC on developing zebrafish were found at 200 mg/L for any of the 19 sublethal impact endpoints assessed. | 5-day EC50 > 200 mg/L | [53] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ede, J.D.; Charlton-Sevcik, A.K.; Griffin, J.; Srinivasan, P.; Zhang, Y.; Sayes, C.M.; Hsieh, Y.-L.; Stark, N.; Shatkin, J.A. Life-Cycle Risk Assessment of Second-Generation Cellulose Nanomaterials. Nanomaterials 2025, 15, 238. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano15030238

Ede JD, Charlton-Sevcik AK, Griffin J, Srinivasan P, Zhang Y, Sayes CM, Hsieh Y-L, Stark N, Shatkin JA. Life-Cycle Risk Assessment of Second-Generation Cellulose Nanomaterials. Nanomaterials. 2025; 15(3):238. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano15030238

Chicago/Turabian StyleEde, James D., Amanda K. Charlton-Sevcik, Julia Griffin, Padmapriya Srinivasan, Yueyang Zhang, Christie M. Sayes, You-Lo Hsieh, Nicole Stark, and Jo Anne Shatkin. 2025. "Life-Cycle Risk Assessment of Second-Generation Cellulose Nanomaterials" Nanomaterials 15, no. 3: 238. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano15030238

APA StyleEde, J. D., Charlton-Sevcik, A. K., Griffin, J., Srinivasan, P., Zhang, Y., Sayes, C. M., Hsieh, Y.-L., Stark, N., & Shatkin, J. A. (2025). Life-Cycle Risk Assessment of Second-Generation Cellulose Nanomaterials. Nanomaterials, 15(3), 238. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano15030238