Scaffold Structural Microenvironmental Cues to Guide Tissue Regeneration in Bone Tissue Applications

Abstract

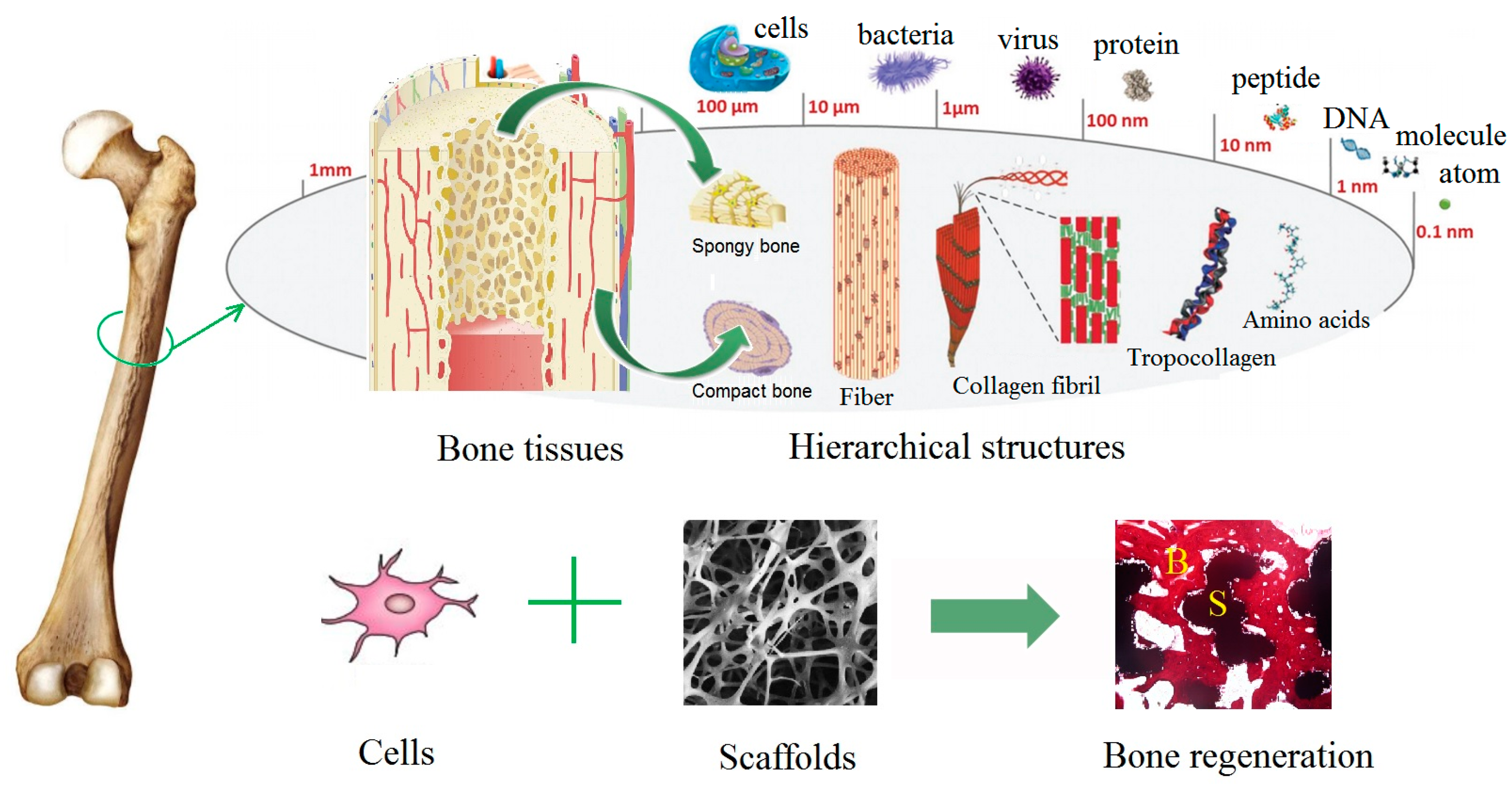

:1. Natural Bone Structure

2. Bone Defects and Bone Tissue Regeneration

3. Effects of Scaffold Structural Cues on Biological Responses

3.1. Porosity and Pore Size Cues

3.2. Grain Size Cues

3.3. Surface Topography of Scaffolds

3.3.1. Microscale Surface Topography

3.3.2. Nanoscale Surface Topography

Nanopits

Nanoislands/Nanocolumns

Nanogrooves

Nanotubes

3.3.3. Potential Mechanisms for Cell Responses to Scaffold Topography

4. Outlook and Perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dvir, T.; Timko, B.; Kohane, D.; Langer, R. Nanotechnological strategies for engineering complex tissues. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2011, 6, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Athanasiou, K.; Zhu, C.; Lanctot, D.; Agrawal, C.; Wang, X. Fundamentals of biomechanics in tissue engineering of bone. Tissue Eng. 2000, 6, 361–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McMahon, R.E.; Wang, L.; Skoracki, R.; Mathur, A.B. Development of nanomaterials for bone repair and regeneration. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. B Appl. Biomater. 2013, 101, 387–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sadat-Shojai, M.; Khorasani, M.-T.; Dinpanah-Khoshdargi, E.; Jamshidi, A. Synthesis methods for nanosized hydroxyapatite indiverse structures. Acta Biommater. 2013, 9, 7591–7621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heo, D.N.; Castro, N.J.; Lee, S.-J.; Noh, H.; Zhu, W.; Zhang, L.G. Enhanced bone tissue regeneration using a 3D printed microstructure incorporated with a hybrid nano hydrogel. Nanoscale 2017, 9, 5055–5062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Li, Q.; Ma, L.; Gao, C. Biomaterials for in situ tissue regeneration: Development and perspectives. J. Mater. Chem. B 2015, 3, 8921–8938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannoudis, P.V.; Dinopoulos, H.; Tsiridis, E. Bone substitutes: An update. Injury 2005, 36, S20–S27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, J.; Chen, H.J.; Zhu, X.D.; Vaidya, S.; Xiang, Z.; Fan, Y.J.; Zhang, X.D. Enhanced repair of a critical-sized segmental bone defect in rabbit femur by surface microstructured porous titanium. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Med. 2014, 25, 1747–1756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albrektsson, T.; Johansson, C. Osteoinduction, osteoconduction and osseointegration. Eur. Spine J. 2001, 10, S96–S101. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Miron, R.; Zhang, Y. Osteoinduction: A review of old concepts with new standards. J. Dent. Res. 2012, 91, 736–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, Z.; Li, X.; Tan, Y.; Fan, H.; Zhang, X. The material and biological characteristics of osteoinductive calcium phosphate ceramics. Regen. Biomater. 2018, 5, 43–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, B.; Pei, X.; Zhou, C.; Fan, Y.; Jiang, Q.; Ronca, A.; D’Amora, U.; Chen, Y.; Li, H.; Sun, Y.; Zhang, X. The biomimetic design and 3D printing of customized mechanical properties porous Ti6Al4V scaffold for load-bearing bone reconstruction. Mater. Des. 2018, 152, 30–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lord, M.S.; Foss, M.; Besenbacher, F. Influence of nanoscale surface topography on protein adsorption and cellular response. Nanotoday 2010, 5, 66–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tawfick, S.; de Volder, M.; Copic, D.; Park, S.J.; Oliver, C.R.; Polsen, E.S.; Roberts, M.J.; Hart, A.J. Engineering of micro- and nanostructured surfaces with anisotropic geometries and properties. Adv. Mater. 2012, 24, 1628–1674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skoog, S.A.; Kumar, G.; Narayan, R.J.; Goering, P.L. Biological responses to immobilized microscale and nanoscale surface topographies. Pharmacol. Ther. 2018, 182, 33–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shirokova, A.G.; Bogdanova, E.A.; Skachkov, V.M.; Pasechnik, L.A.; Borisov, S.V.; Sabirzyanov, N.A. Bioactive coatings of porous materials: Fabrication and properties. J. Surf. Investig. X-ray Synchrotron Neutron Tech. 2017, 11, 107–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, P.; Zhou, C.; Fan, H.; Zhang, B.; Pei, X.; Fan, Y.; Jiang, Q.; Bao, R.; Yang, Q.; Dong, Z.; Zhang, X. Novel 3D porous biocomposite scaffolds fabricated by fused deposition modeling and gas foaming combined technology. Compos. Part B Eng. 2018, 143, 243–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalilottojari, A.; Delalat, B.; Harding, F.J.; Cockshell, M.P.; Bonder, C.S.; Voelcker, N.H. Porous silicon-based cell microarrays: optimizing human endothelial cell-material surface interactions and bioactive release. Biomacromolecules 2006, 17, 3724–3731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Camilo, C.C.; Silveira, C.A.E.; Faeda, R.S.; Rollo, J.M.D.d.; Purquerio, B.M.; Fortulan, C.A. Bone response to porous alumina implants coated with bioactive materials, observed using different characterization techniques. J. Appl. Biomater. Funct. Mater. 2017, 15, e223–e235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuttor, A.; Szalóki, M.; Rente, T.; Kerényi, F.; Bakó, J.; Fábián, I.; Lázár, I.; Jenei, A.; Hegedüs, C. Preparation and application of highly porous aerogel-based bioactive materials in dentistry. Front. Mater. Sci. 2014, 8, 46–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolan, K.C.R.; Leu, M.C.; Hilmas, G.E.; Velez, M. Effect of material, process parameters, and simulated body fluids on mechanical properties of 13-93 bioactive glass porous constructs made by selective laser sintering. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2012, 13, 14–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fujibayashi, S.; Takemoto, M.; Neo, M.; Matsushita, T.; Kokubo, T.; Doi, K.; Ito, T.; Shimizu, A.; Nakamura, T. A novel synthetic material for spinal fusion: A prospective clinical trial of porous bioactive titanium metal for lumbar interbody fusion. Eur. Spine J. 2011, 20, 1486–1495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Zhang, B.; Pei, X.; Song, P.; Sun, H.; Li, H.; Fan, Y.; Jiang, Q.; Zhou, C.; Zhang, X. Porous bioceramics produced by inkjet 3D printing: effect of printing ink formulation on the ceramic macro and micro porous architectures control. Compos. Part B Eng. 2018, 155, 112–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walpole, A.R.; Xia, Z.; Wilson, C.W.; Triffitt, J.T.; Wilshaw, P.R. A novel nano-porous alumina biomaterial with potential for loading with bioactive materials. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A 2009, 90, 46–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schumacher, M.; Deisinger, U.; Ziegler, G.; Detsch, R. Indirect rapid prototyping of biphasic calcium phosphate scaffolds as bone substitutes: Influence of phase composition, macroporosity and pore geometry on mechanical properties. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Med. 2010, 21, 3119–3127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, C.; Ramaswamy, Y.; Zreiqat, H. Porous diopside (CaMgSi2O6) scaffold: A promising bioactive material for bone tissue engineering. Acta Biomater. 2010, 6, 2237–2245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pe, X.; Ma, L.; Zhang, B.; Sun, J.; Sun, Y.; Fan, Y.; Gou, Z.; Zhou, C.; Zhang, X. Creating hierarchical porosity hydroxyapatite scaffolds with osteoinduction by three-dimensional printing and microwave sintering. Biofabrication 2017, 9, 045008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daugela, P.; Pranskunas, M.; Juodzbalys, G.; Liesiene, J.; Baniukaitiene, O.; Afonso, A.; Gomes, P.S. Novel cellulose/hydroxyapatite scaffolds for bone tissue regeneration: In vitro and in vivo study. J. Tissue Eng. Regen. Med. 2018, 12, 1195–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, F.; Garrigle, M.J.M.; Vaughan, T.J.; McNamara, L.M. In silico study of bone tissue regeneration in an idealised porous hydrogel scaffold using a mechano-regulation algorithm. Biomech. Model. Mechanobiol. 2018, 17, 5–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raafat, A.; Abd-Allah, W. In vitro apatite forming ability and ketoprofen release of radiation synthesized (gelatin-polyvinyl alcohol)/bioglass composite scaffolds for bone tissue regeneration. Polym. Compos. 2018, 39, 606–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shim, K.; Kim, S.; Yun, Y.; Jeon, D.; Kim, H.; Park, K.; Song, H. Surface immobilization of biphasic calcium phosphate nanoparticles on 3D printed poly(caprolactone) scaffolds enhances osteogenesis and bone tissue regeneration. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2017, 55, 101–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Yang, G.H.; Kim, M.; Lee, J.Y.; Huh, J.T.; Kim, G.H. Fabrication of micro/nanoporous collagen/dECM/silk-fibroin biocomposite scaffolds using a low temperature 3D printing process for bone tissue regeneration. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2017, 84, 140–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xue, C.; Ren, H.; Zhu, H.; Gu, X.; Guo, Q.; Zhou, Y.; Huang, J.; Wang, S.; Zha, G.; Gu, J.; et al. Bone marrow mesenchymal stem cell-derived acellular matrix-coated chitosan/silk scaffolds for neural tissue regeneration. J. Mater. Chem. B 2017, 5, 1246–1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, H.; Ikoma, T.; Bao, C.; Wang, H.; Zhang, L.; Tanaka, J.; Zhang, X. Surface characteristics and osteoinductivity of biphasic calcium phosphate ceramics with different sintering temperature. Key Eng. Mater. 2006, 309–311, 1299–1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habibovic, P.; Yuan, H.; van der Valk, C.M.; Meijer, G.; van Blitterswijk, C.A.; de Groot, K. 3D microenvironment as essential element for osteoinduction by biomaterials. Biomaterials 2005, 26, 3565–3575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fellah, B.H.; Gauthier, O.; Weiss, P.; Chappard, D.; Layrolle, P. Osteogenicity of biphasic calcium phosphate ceramics and bone autograft in a goat model. Biomaterials 2008, 29, 1177–1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Yuan, H.; Fernandes, H.; Habibovic, P.; de Boer, J.; Barradas, A.M.C.; de Ruiter, A. Osteoinductive ceramics as a synthetic alternative to autologous bone grafting. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 10–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davison, N.L.; Su, J.; Yuan, H.; van den Beucken, J.J.J.P.; de Bruijn, J.D.; de Groot, F.B. Influence of surface microstructure and chemistry on osteoinduction and osteoclastogenesis by biphasic calcium phosphate discs. Eur. Cells Mater. 2015, 29, 314–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habibovic, P.; Yuan, H.; van den Doel, M.; Sees, T.; van Blitterswijk, C.; de Groot, K. Relevance of osteoinductive biomaterials in critical-sized orthotopic defect. J. Orthop. Res. 2006, 24, 867–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Habibovic, P.; Sees, T.M.; van den Doel, M.A.; van Blitterswijk, C.A.; de Groot, K. Osteoinduction by biomaterials—Physicochemical and structural influences. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A 2006, 77, 747–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Luo, X.; Barbieri, D.; Barradas, A.M.C.; de Bruijn, J.D.; van Blitterswijk, C.A.; Yuan, H. The size of surface microstructures as an osteogenic factor in calcium phosphate ceramics. Acta Biomater. 2014, 10, 3254–3263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davison, N.; Luo, X.; Schoenmaker, T.; Everts, V.; Yuan, H.; Barrère-de Groot, F.; de Bruijn, J. Submicron-scale surface architecture of tricalcium phosphate directs osteogenesis in vitro and in vivo. Eur. Cell Mater. 2014, 27, 281–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davison, N.L.; Gamblin, A.L.; Layrolle, P.; Yuan, H.; de Bruijn, J.D.; Groot, F.B. Liposomal clodronate inhibition of osteoclastogenesis and osteoinduction by submicrostructured beta-tricalcium phosphate. Biomaterials 2014, 35, 5088–5097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.S.; Baek, S.D.; Venkatesan, J.; Bhatnagar, I.; Chang, H.K.; Kim, H.T.; Kim, S.K. In vivo study of chitosan-natural nano hydroxyapatite scaffolds for bone tissue regeneration. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2014, 67, 360–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alothman, O.Y.; Almajhdi, F.N.; Fouad, H. Effect of gamma radiation and accelerated aging on the mechanical and thermal behavior of HDPE/HA nano-composites for bone tissue regeneration. Biomed. Eng. Online 2013, 12, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Wang, X.; Fan, H.; Xiao, Y.; Zhang, X. Fabrication and characterization of porous hydroxyapatite/β-tricalcium phosphate ceramics by microwave sintering. Mater. Lett. 2006, 60, 455–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Chen, X.; Guo, B.; Wang, X.; Fan, H.; Zhang, X. Fabrication and cellular biocompatibility of porous carbonated biphasic calcium phosphate ceramics with a nanostructure. Acta Biomater. 2009, 5, 134–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Z.; Tang, Z.; Qing, F.; Hong, Y. Applications of calcium phosphate nanoparticles in porous hard tissue. Nanobr. Rep. Rev. 2012, 7, 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Suwandi, J.S.; Toes, R.E.M.; Nikolic, T.; Roep, B.O. Inducing tissue specific tolerance in autoimmune disease with tolerogenic dendritic cells. Clin. Exp. Rheumatol. 2015, 33, 97–103. [Google Scholar]

- Ho, Y.C.; Huang, F.M.; Chang, Y.C. Cytotoxicity of formaldehyde on human osteoblastic cells is related to intracellular glutathione levels. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. B Appl. Biomater. 2007, 83, 340–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liao, X.; Lu, S.; Zhuo, Y.; Winter, C.; Xu, W.; Li, B.; Wang, Y. Bone physiology, biomaterial and the effect of mechanical/physical microenvironment on MSC osteogenesis: A tribute to Shu Chien’s 80th Birthday. Cell. Mol. Bioeng. 2011, 4, 579–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- LeGeros, R. Biodegradation and bioresorption of calcium phosphate ceramics. Clin. Mater. 1993, 14, 65–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, K.; Chang, J.; Lu, J.; Wu, W.; Zeng, Y. Properties of b-Ca3(PO4)2 bioceramics prepared using nano-sized powders. Ceram. Int. 2007, 33, 979–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, Y.; Yan, H.; Wang, X.; Zhu, B.; Ning, C.; Ge, S. Evaluation of osteoinduction and proliferation on nano-Sr-HAP: A novel orthopedic biomaterial for bone tissue regeneration. J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 2012, 12, 207–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pielichowska, K.; Blazewicz, S. Bioactive polymer/hydroxyapatite (Nano)composites for bone tissue regeneration. Adv. Polym. Sci. 2010, 232, 97–207. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Shaw, L. Morphology-enhanced low-temperature sintering of nanocrystalline hydroxyapatite. Adv. Mater. 2007, 19, 2364–2369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webster, T.; Ergun, C.; Doremus, R.; Seigel, R.; Bizios, R. Enhanced osteoclast–like functions on nanophase ceramics. Biomaterials 2001, 22, 1327–1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, M.; Sambito, M.A.; Aslani, A.; Kalkhoran, N.M.; Slamovich, E.B.; Webster, T.J. Increased osteoblast functions on undoped and yttrium-doped nanocrystalline hydroxyapatite coatings on titanium. Biomaterials 2006, 27, 2358–2369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thian, E.S.; Huang, J.; Best, S.M.; Barber, Z.H.; Brooks, R.A.; Rushton, N.; Bonfield, W. The response of osteoblasts to nanocrystalline silicon-substituted hydroxyapatite thin films. Biomaterials 2006, 27, 2692–2698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.W.; Kim, H.E.; Salih, V. Stimulation of osteoblast responses to biomimetic nanocomposites of gelatin-hydroxyapatite for tissue engineering scaffolds. Biomaterials 2005, 26, 5221–5230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, W.; Chu, C.; Wang, J.; Zhao, H. Comparison of periodontal ligament cells responses to dense and nanophase hydroxyapatite. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Med. 2007, 18, 677–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, Y.; Fan, H.; Li, B.; Guo, B.; Liu, M.; Zhang, X. Fabrication, biological effects, and medical applications of calcium phosphate nanoceramics. Mater. Sci. Eng. R. Rep. 2010, 70, 225–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sari, D.; Bang, S.; Nguyen, L.; Cho, Y.; Park, K.; Lee, S. Micro/nano surface topography and 3D bioprinting of biomaterials in tissue engineering. J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 2016, 16, 8909–8922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, S.; Popowich, Y.; Greco, R.S.; Haimovich, B. Neutrophil survival on biomaterials is determined by surface topography. J. Vasc. Surg. 2003, 37, 1082–1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McBeath, R.; Pirone, D.M.; Nelson, C.M.; Bhadriraju, K.; Chen, C.S. Cell shape, cytoskeletal tension, and RhoA regulate stemm cell lineage commitment. Dev. Cell 2004, 6, 483–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maduram, J.; Goluch, E.; Hu, H.; Liu, C.; Mrksich, M. Subcellular curvature at the perimeter of micropatterned cells influences lamellipodial distribution and cell polarity. Cell Motil. Cytoskelet. 2008, 65, 841–852. [Google Scholar] [Green Version]

- Kilian, K.A.; Bugarija, B.; Lahn, B.T.; Mrksich, M. Geometric cues for directing the differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 4872–4877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Wang, R.; Hu, Y.X. Patterning hydroxyapatite biocoating by electrophoretic deposition. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A 2003, 67, 270–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teshima, K.; Lee, S.; Yubuta, K.; Mori, S.; Shishido, T.; Oishi, S. Selective growth of highly crystalline hydroxyapatite in a micro-reaction cell of agar gel. CrystEngComm 2011, 13, 827–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tseng, Y.H.; Birkbak, M.E.; Birkedal, H. Spatial organization of hydroxyapatite nanorods on a substrate via a biomimetic approach. Cryst. Growth Des. 2013, 13, 4213–4219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Zhu, X.; Fan, H.; Zhang, X. Rat bone marrow cell responses on the surface of hydroxyapatite with different topography. Key Eng. Mater. 2008, 363, 1107–1110. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X.; Chen, X.; Zhu, X.; Cai, B.; Fan, H.; Zhang, X. Effect of surface topography of hydroxyapatite on Human osteosarcoma MG-63 cell. J. Inorg. Mater. 2013, 28, 901–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, B.; Chang, J.; Lin, K. Designing ordered micropatterned hydroxyapatite bioceramics to promote the growth and osteogenic differentiation of bone marrow stromal cells. J. Mater. Chem. B Mater. Biol. Med. 2015, 3, 968–976. [Google Scholar]

- Rho, J.; Kuhn-Spearing, L.; Zioupos, P. Mechanical properties and the hierarchical structure of bone. Med. Eng. Phys. 1998, 20, 92–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, S.; Hsu, F.; Chen, P. Beads of collagen-nanohydroxyapatite composites prepared by a biomimetic process and the effects of their surface texture on cellular behavior in MG63 osteoblast-like cells. Acta Biomater. 2008, 4, 1332–1341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, C.; Storey, D.; Webster, T. Nanostructured metal coatings on polymers increase osteoblast attachment. Int. J. Nanomed. 2007, 2, 487–492. [Google Scholar]

- Steinmüller-Nethl, G.; Kloss, D.; Najam-Ul-Haq, F.R.; Rainer, M.; Larsson, M.; Linsmeier, K.; Köhler, C.; Fehrer, G.; Lepperdinger, C.; Liu, G.; et al. Strong binding of bioactive BMP-2 to nanocrystalline diamond by physisorption. Biomaterials 2006, 27, 4547–4556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dalby, M.J.; Gadegaard, N.; Tare, R.; Andar, A.; Riehle, M.O.; Herzyk, P.; Wilkinson, C.D.W.; Oreffo, R.O.C. The control of human mesenchymal cell differentiation using nanoscale symmetry and disorder. Nat. Mater. 2007, 6, 997–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kingham, E.; White, K.; Gadegaard, N.; Dalby, M.J.; Oreffo, R.O.C. Nanotopographical cues augment mesenchymal differentiation of human embryonic stem cells. Small 2013, 9, 2140–2151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allan, C.; Ker, A.; Smith, C.-A.; Tsimbouri, P.M.; Borsoi, J.; O’Neill, S.; Gadegaard, N.; Dalby, M.J.; Meek, R.D. Osteoblast response to disordered nanotopography. J. Tissue Eng. 2018, 9, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gallagher, J.; McGhee, K.; Wilkinson, C.; Riehle, M. Interaction of animal cells with ordered nanotopography. IEEE Trans. Nanobiosci. 2002, 1, 24–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalby, M.J.; Gadegaard, N.; Riehle, M.O.; Wilkinson, C.D.W.; Curtis, A.S.G. Investigating filopodia sensing using arrays of defined nano-pits down to 35 nm diameter in size. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2004, 36, 2015–2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andersson, A.; Backhed, F.; von Euler, A.; Richter-Dahlfors, A.; Sutherland, D.; Kasemo, B. Nanoscale features influence epithelial cell morphology and cytokine production. Biomaterials 2003, 24, 3427–3436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalby, M.J.; Riehle, M.O.; Johnstone, H.; Affrossman, S.; Curtis, A.S.G. In vitro reaction of endothelial cells to polymer demixed nanotopography. Biomaterials 2002, 23, 2945–2954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalby, M.J.; Childs, S.; Riehle, M.O.; Johnstone, H.J.H.; Affrossman, S.; Curtis, A.S.G. Fibroblast reaction to island topography: Changes in cytoskeleton and morphology with time. Biomaterials 2003, 24, 927–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalby, M.J.; Riehle, M.O.; Sutherland, D.S.; Agheli, H.; Curtis, A.S.G. Changes in fibroblast morphology in response to nano-columns produced by colloidal lithography. Biomaterials 2004, 25, 5415–5422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dalby, M.J.; Riehle, M.O.; Johnstone, H.; Affrossman, S.; Curtis, A.S.G. Investigating the limits of filopodial sensing: A brief report using SEM to image the interaction between 10 nm high nano-topography and fibroblast filopodia. Cell Biol. Int. 2004, 28, 229–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dalby, M.J.; Giannaras, D.; Riehle, M.O.; Gadegaard, N.; Affrossman, S.; Curtis, A.S.G. Rapid fibroblast adhesion to 27 nm high polymer demixed nano-topography. Biomaterials 2004, 25, 77–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rice, J.; Hunt, J.; Gallagher, J.; Hanarp, P.; Sutherland, D.; Gold, J. Quantitative assessment of the response of primary derived human osteoblasts and macrophages to a range of nanotopography surfaces in a single culture model in vitro. Biomaterials 2003, 24, 4799–4818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biggs, M.J.P.; Richards, R.G.; Gadegaard, N.; McMurray, R.J.; Affrossman, S.; Wilkinson, C.D.W.; Oreffo, R.O.C.; Dalby, M.J. Interactions with nanoscale topography: Adhesion quantification and signal transduction in cells of osteogenic and multipotent lineage. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A 2009, 91, 195–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dalby, M.J.; McCloy, D.; Robertson, M.; Agheli, H.; Sutherland, D.; Affrossman, S.; Oreffo, R.O.C. Osteoprogenitor response to semi-ordered and random nanotopographies. Biomaterials 2006, 27, 2980–2987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnstone, S.A.; Liley, M.; Dalby, M.J.; Barnett, S.C. Comparison of human olfactory and skeletal MSCs using osteogenic nanotopography to demonstrate bone-specific bioactivity of the surfaces. Acta Biomater. 2015, 13, 266–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, J.Y.; Ting, Y.C.; Lai, J.Y.; Liu, H.L.; Fang, H.W.; Tsai, W.B. Quantitative analysis of osteoblast-like cells (MG63) morphology on nanogrooved substrata with various groove and ridge dimensions. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A 2009, 90, 629–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fujita, S.; Ohshima, M.; Iwata, H. Time-lapse observation of cell alignment on nanogrooved patterns. J. R. Soc. Interface 2009, 6, S269–S277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Diehl, K.A.; Foley, J.D.; Nealey, P.F.; Murphy, C.J. Nanoscale topography modulates corneal epithelial cell migration. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A 2005, 75, 603–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.; Bae, W.G.; Choung, H.W.; Lim, K.T.; Seonwoo, H.; Jeong, H.E.; Suh, K.Y.; Jeon, N.L.; Choung, P.H.; Chung, J.H. Multiscale patterned transplantable stem cell patches for bone tissue regeneration. Biomaterials 2014, 35, 9058–9067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.; Kim, H.N.; Lim, K.T.; Kim, Y.; Seonwoo, H.; Park, S.H.; Lim, H.J.; Kim, D.H.; Suh, K.Y.; Choung, P.H.; et al. Designing nanotopographical density of extracellular matrix for controlled morphology and function of human mesenchymal stem cells. Sci. Rep. 2013, 3, 3552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kim, D.; Kim, J.; Hyun, H.; Kim, K.; Roh, S. A nanoscale ridge/groove pattern arrayed surface enhances adipogenic differentiation of human supernumerary tooth-derived dental pulp stem cells in vitro. Arch. Oral Biol. 2014, 59, 765–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abagnale, G.; Steger, M.; Nguyen, V.H.; Hersch, N.; Sechi, A.; Joussen, S.; Denecke, B.; Merkel, R.; Hoffmann, B.; Dreser, A.; et al. Surface topography enhances differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells towards osteogenic and adipogenic lineages. Biomaterials 2015, 61, 316–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loesberg, W.A.; te Riet, J.; van Delft, F.C.; Schön, P.; Figdor, C.G.; Speller, S.; van Loon, J.J.; Walboomers, X.F.; Jansen, J.A. The threshold at which substrate nanogroove dimensions may influence fibroblast alignment and adhesion. Biomaterials 2007, 28, 3944–3951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McNamara, L.E.; Sjöström, T.; Seunarine, K.; Meek, R.D.; Su, B.; Dalby, M.J. Investigation of the limits of nanoscale filopodial interactions. J. Tissue Eng. 2014, 5, 326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Minagar, S.; Wang, J.; Berndt, C.C.; Ivanova, E.P.; Wen, C. Cell response of anodized nanotubes on titanium and titanium alloys. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A 2013, 101, 2726–2739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brammer, K.S.; Kim, H.; Noh, K.; Loya, M.; Frandsen, C.J.; Chen, L.H.; Connelly, L.S.; Jin, S. Highly bioactive 8 nm hydrothermal TiO2 nanotubes elicit enhanced bone cell response. Adv. Eng. Mater. 2011, 13, 88–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Wilmowsky, C.; Bauer, S.; Lutz, R.; Meisel, M.; Neukam, F.W.; Toyoshima, T.; Schmuki, P.; Nkenke, E.; Schlegel, K.A. In vivo evaluation of anodic TiO2 nanotubes: An experimental study in the pig. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. B Appl. Biomater. 2009, 89, 165–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bauer, M.S.P. Nanosize and vitality: TiO2 nanotube diameter directs cell fate. Nano Lett. 2007, 7, 1686–1691. [Google Scholar]

- Park, J.; Bauer, S.; Schlegel, K.A.; Neukam, F.W.; der von Mark, K.; Schmuki, P. TiO2 nanotube surfaces: 15 nm–an optimal length scale of surface topography for cell adhesion and differentiation. Small 2009, 5, 666–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brammer, K.S.; Oh, S.; Cobb, C.J.; Bjursten, L.M.; van der Heyde, H.; Jin, S. Improved bone-forming functionality on diameter-controlled TiO2nanotube surface. Acta Biomater. 2009, 5, 3215–3223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsimbouri, P.M.; Gadegaard, N.; Oreffo, R.O.C.; Dalby, M.J. Effects of nanotopography on cell adhesion, morphology and differentiation. Eur. Cells Mater. 2011, 22, 14. [Google Scholar]

- Tsimbouri, P.M.; Murawski, K.; Hamilton, G.; Herzyk, P.; Oreffo, R.O.C.; Gadegaard, N.; Dalby, M.J. A genomics approach in determining nanotopographical effects on MSC phenotype. Biomaterials 2013, 34, 2177–2184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.R.; Ahmed, S.F.; Gadegaard, N.; Meek, R.M.D.; Dalby, M.J.; Yarwood, S.J. Nanotopology potentiates growth hormone signalling and osteogenesis of mesenchymal stem cells. Growth Horm. IGF Res. 2014, 24, 245–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dalby, M.J.; Gadegaard, N.; Oreffo, R.O.C. Harnessing nanotopography and integrin-matrix interactions to influence stem cell fate. Nat. Mater. 2014, 13, 558–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hynes, R.O. Integrins: Bidirectional, allosteric signaling machines. Cell 2002, 110, 673–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shekaran, A.; García, A.J. Extracellular matrix-mimetic adhesive biomaterials for bone repair. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. A 2011, 96, 261–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.; Wang, J.; Chen, Y.; Cai, H.; Yang, X.; Zhu, X.; Fan, Y.; Zhang, X. Roles of calcium phosphate-mediated integrin expression and MAPK signaling pathways in the osteoblastic differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells. J. Mater. Chem. B 2016, 4, 2280–2289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Docheva, D.; Popov, C.; Mutschler, W.; Schieker, M. Human mesenchymal stem cells in contact with their environment: Surface characteristics and the integrin system. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2007, 11, 21–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, X.D.; Zhang, H.J.; Fan, H.S.; Li, W.; Zhang, X.D. Effect of phase composition and microstructure of calcium phosphate ceramic particles on protein adsorption. Acta Biomater. 2010, 6, 1536–1541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arima, Y.; Iwata, H. Effect of wettability and surface functional groups on protein adsorption and cell adhesion using well-defined mixed self-assembled monolayers. Biomaterials 2007, 28, 3074–3082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, X.D.; Fan, H.S.; Xiao, Y.M.; Li, D.X.; Zhang, H.J.; Luxbacher, T.; Zhang, X.D. Effect of surface structure on protein adsorption to biphasic calcium-phosphate ceramics in vitro and in vivo. Acta Biomater. 2009, 5, 1311–1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmidt, S.; Friedl, P. Interstitial cell migration: Integrin-dependent and alternative adhesion mechanisms. Cell Tissue Res. 2010, 339, 83–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ozdemir, T.; Higgins, A.M.; Brown, J.L. Osteoinductive biomaterial geometries for bone regenerative engineering. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2013, 19, 3446–3455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, N.; Tytell, J.D.; Ingber, D.E. Mechanotransduction at a distance: Mechanically coupling the extracellular matrix with the nucleus. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2009, 10, 75–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McNamara, L.E.; McMurray, R.J.; Biggs, M.J.P.; Kantawong, F.; Oreffo, R.O.C.; Dalby, M.J. Nanotopographical control of stem cell differentiation. J. Tissue Eng. 2010, 1, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chen, X.; Fan, H.; Deng, X.; Wu, L.; Yi, T.; Gu, L.; Zhou, C.; Fan, Y.; Zhang, X. Scaffold Structural Microenvironmental Cues to Guide Tissue Regeneration in Bone Tissue Applications. Nanomaterials 2018, 8, 960. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano8110960

Chen X, Fan H, Deng X, Wu L, Yi T, Gu L, Zhou C, Fan Y, Zhang X. Scaffold Structural Microenvironmental Cues to Guide Tissue Regeneration in Bone Tissue Applications. Nanomaterials. 2018; 8(11):960. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano8110960

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Xuening, Hongyuan Fan, Xiaowei Deng, Lina Wu, Tao Yi, Linxia Gu, Changchun Zhou, Yujiang Fan, and Xingdong Zhang. 2018. "Scaffold Structural Microenvironmental Cues to Guide Tissue Regeneration in Bone Tissue Applications" Nanomaterials 8, no. 11: 960. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano8110960

APA StyleChen, X., Fan, H., Deng, X., Wu, L., Yi, T., Gu, L., Zhou, C., Fan, Y., & Zhang, X. (2018). Scaffold Structural Microenvironmental Cues to Guide Tissue Regeneration in Bone Tissue Applications. Nanomaterials, 8(11), 960. https://doi.org/10.3390/nano8110960