5.1. Tourist Assets of Landscape Parks

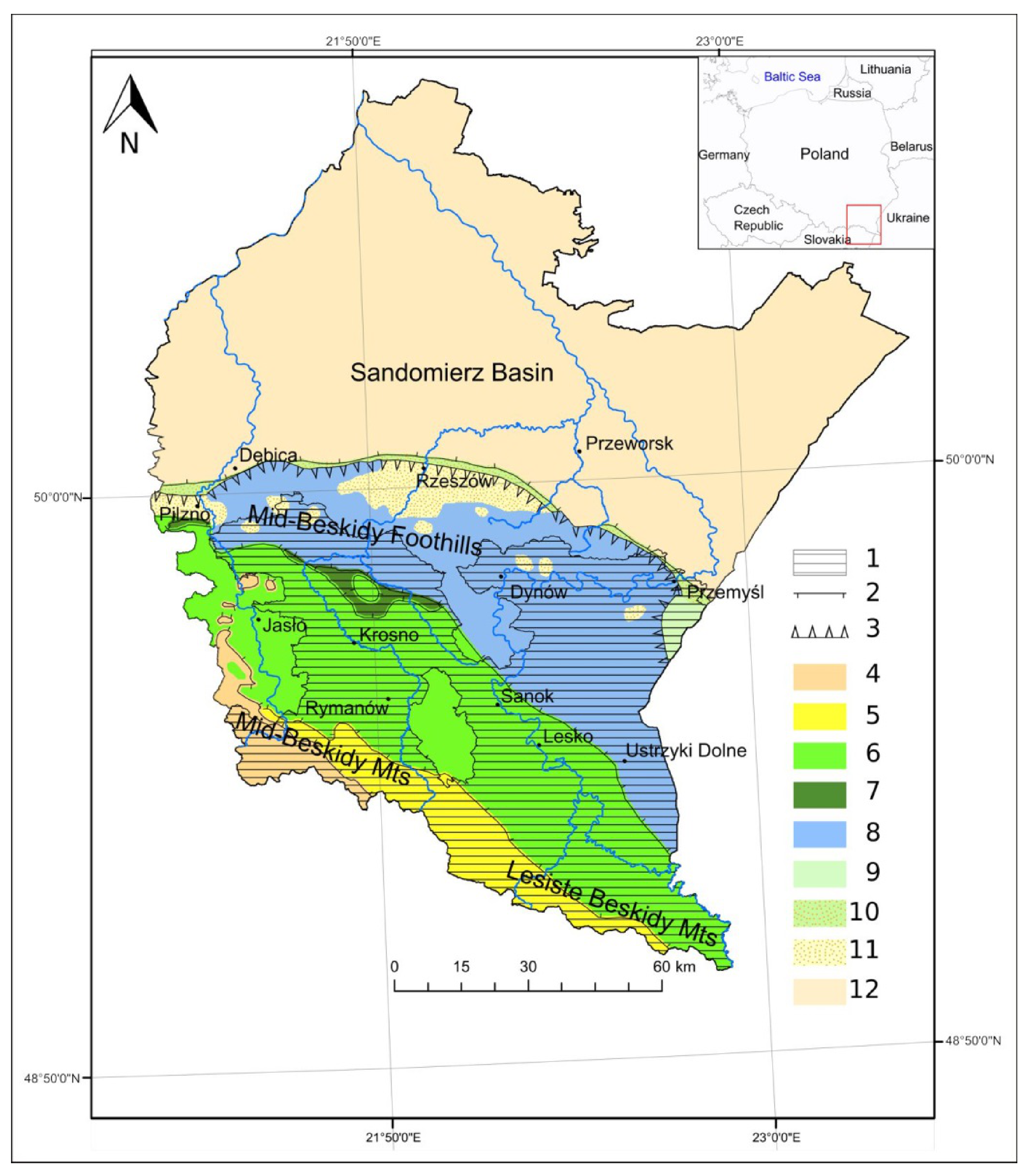

The tourist attractiveness of a specific area consists of natural environment and cultural assets, tourist development and transport accessibility. A significant factor is the tourism policies conducted at different levels of government in a given country, including policies related to the organisation of the tourism management system and support of its development, including financial support. Owing to the cultural and natural heritage and landscape values, the area of the Carpathians in the Podkarparckie Province is indicated in national and regional strategy and planning documents as predisposed to the development of leisure and tourism [

64,

65]. Since no geopark has been established in the Polish Carpathians yet, the tourist asset assessments thus far have been conducted within landscape parks.

Warszyńska and her team (1980) [

66] conducted a tourist attractiveness assessment for the natural environment assets of the Carpathian landscape parks. Taking into account the mean values of indicators for localities administratively linked to landscape parks, she assessed the tourist attractiveness of the individual parks. Among the parks that could become geoparks, the Cisna-Wetlina Landscape Park and the San Valley Landscape Park have been assigned the highest category in the general attractiveness category (

Table 5). A high general tourist attractiveness is indicative of favourable conditions for tourism throughout the year, and thus the possibility of developing tourism as the main or equivalent function [

67].

According to the methodological framework prepared by Warszyńska (1985) [

66], Zawilińska (2010) [

54] assessed the tourist function of districts administratively linked with landscape parks, taking into account the size of accommodation infrastructure in relation to the number of inhabitants and area of districts. In the functional structure, tourism has a very high significance in districts administratively associated with the Cisna-Wetlina LP and the San Valley LP. It constitutes the main—or one of the main—functions in the economy of the districts of Cisna and Solina, or an equivalent or supplementary function in the districts of Lutowiska and Czarna as well as the district of Krempna in the Jaśliska LP and district of Lesko in the Słonne Mountains LP. In some districts, it is a supplementary function, e.g., Komańcza, Jaśliska, Ustrzyki Dolne, Sanok, Fredropol, Krasiczyn. On the other hand, the tourist function is the least developed (in an initial stage) in the districts in the western part of the Słonne Mountains LP and Pogórze Przemyskie LP as well as in some districts in which the Czarnorzeki-Strzyżów LP is located. In the Pogórze Przemyskie LP and the Czarnorzeki-Strzyżów LP, there are districts where the development of the tourist function has not begun yet.

Zawilińska (2010) [

54] used the SWOT analysis to assess the possibilities for the development of tourism in the landscape parks of the Carpathians. Based on that analysis and the assessment of the tourist potential of the natural environment and cultural assets, as well as the level of tourism infrastructure development, she distinguished models of tourism and identified the possibilities and directions of the sustainable development of tourism. In total, she distinguished seven types of landscape parks, according to the characteristics of the tourist function, and formulated four development models for them. In the area of the landscape parks that were indicated as potential geoparks in the Podkarpackie Province, she distinguished three types and two development models (

Table 6). Although the abiotic potential was not the subject of a separate assessment, the specific directions of development are universal and can be pursued based on tourist products prepared within the geoparks.

The above assessments of districts administratively linked with landscape parks show that the area analysed has a significant tourist potential. Tourism in landscape parks takes advantage of a variety of tourist assets. At the same time, its development hinges on transport accessibility along with the development of tourist infrastructure that will enable pursuit of a given form of tourism. In areas with valuable natural environment assets, the development of mass tourism is not recommended because this form of tourism leads to intensive land development and considerable motor vehicle traffic. In such cases, sightseeing tourism, particularly forms relying on the unique assets of a given area, and ecotourism are preferred. The results of studies by various authors [

54,

66,

67] indicate a very high tourist attractiveness of districts in the Cisna-Wetlina LP and San Valley LP. In their case, the primacy of nature conservation should determine the development of tourism. The tourist function is of enormous significance for the economy of these areas. The situation is similar in the case of the districts of the Jaśliska LP, Słonne Mountains LP and Pogórze Przemyskie LP, where low tourist capacity is accompanied by average tourist assets. The tourist assets in the districts of the Czarnorzeki-Strzyżów LP received the lowest rating. At the same time, these areas show valuable abiotic assets that have justified proposals for establishing geoparks [

20,

21,

22].

5.2. Prospects for the Establishment of Geoparks

Geoparks may play a very significant role in the development of tourism in a given area and may thus foster regional development [

68,

69]. Therefore, efforts to establish geoparks are undertaken in many areas. However, a given area must meet specific criteria in order to become a geopark. In the case of the European Geoparks Network, the criteria are as follows [

70]:

- (1)

A geopark is an area that comprises unique geological heritage and has a strategy of sustainable territorial development. It must have clearly defined boundaries and sufficient areas allowing real territorial economic development.

- (2)

It must consist of a specific number of geological sites of special significance in terms of scientific value, rarity, aesthetic value or educational value. Most sites located within a geopark must be part of the geological heritage, but they may also be of an archaeological, ecological, historical or cultural nature.

- (3)

A geopark plays an active role in the economic growth of its area by improving the overall image based on geological heritage and development of geotourism.

- (4)

A European geopark has a direct impact on its territory, influencing the living conditions and environment of its inhabitants. Its establishment should be aimed at enabling residents to take advantage of the economic potential offered by the local geoheritage, and to actively manage the entire territory.

In the case of Global Geoparks, the assessment is carried out according to the following criteria: Geology and Landscape; Geoconservation (25%); Natural and Cultural Heritage (10%); Management Structure (25%); Interpretation and Environmental education (15%); Geotourism (15%); Sustainable Regional Economic Development (10%). (

https://en.unesco.org/global-geoparks accessed on 6 September 2021). In the case of the potential geoparks, the condition related to the occurrence of valuable geological and geomorphological heritage assets is met. Inanimate nature reserves, inanimate natural monument and geosites occur in the area of the potential geoparks. However, they are not evenly distributed. The situation is similar in the case of cultural and natural heritage. The lack of formal regulations concerning the establishment of geoparks and their functioning in the administration structure is a very serious challenge. Alongside the UNESCO geoparks and two national geoparks existing in Poland, over 25 areas have been initially proposed as potential geoparks in the future [

6]. Some of the geoparks, e.g., the Małopolska Vistula Gap or the Stone Forest in Roztocze, have detailed scientific documentation, while in the case of other geoparks, the development of documentation is clearly less advanced [

71]. Unfortunately, the work stops at this stage in most cases. There is a lack of institutional support for local governments, which definitely makes it difficult to create structures for the management of geoparks. Therefore, it is particularly important to prepare regional development strategies that would take into account the possibility of establishing geoparks [

72,

73]. Thus far, studies on the directions of tourism development in the Podkarpackie Province have been conducted in districts located within landscape parks. The development of tourism and education exclusively based on geological and geomorphological assets can be difficult, at least in the initial stage. Therefore, it would seem advisable to develop tourism based on all the assets occurring in the area, with a particular focus on the geoheritage, before proceeding with any possible efforts to establish geoparks.

Based on the results of the assessment of potentials, with a particular focus on geoheritage, and the results of clustering, it should be assumed that the geopark in the Bieszczady Wysokie Mountains and the Wisłok Valley—the Polish Texas Geopark are the best proposals that are the most likely to work. In both cases, the abiotic assets are very valuable. A SWOT analysis has been carried out for districts administratively linked with the potential geoparks (

Table 7 and

Table 8). Factors in the following categories have been considered: geoheritage, animate nature, cultural resources, tourism development and socio-economic situation. The internal determinants (strengths and weaknesses) include an assessment of the current situation in the districts, while the external determinants (opportunities and threats) represent the existing external factors and those that may arise in the future (also within a district). The supplementary resources used consist of the following: scientific monographs and articles, statistical data obtained from Statistics Poland 55 and indicators calculated on their basis, strategy and planning studies, spatial data, websites and field surveys. The SWOT analysis has enabled broader strategic inferencing and indicated the directions of the sustainable development of tourism. According to the SWOT analysis for geoheritage and biotic and cultural resources for the districts within which the two proposed geoparks would be located, the strengths have a significant advantage over the weaknesses. The existing opportunities may strengthen these advantages and contribute to the development of the region. On the other hand, tourist development, and the socio-economic determinants in particular, has a much weaker position, and it is necessary to take advantage of the existing opportunities and, above all, to mitigate the weaknesses and avoid the threats.

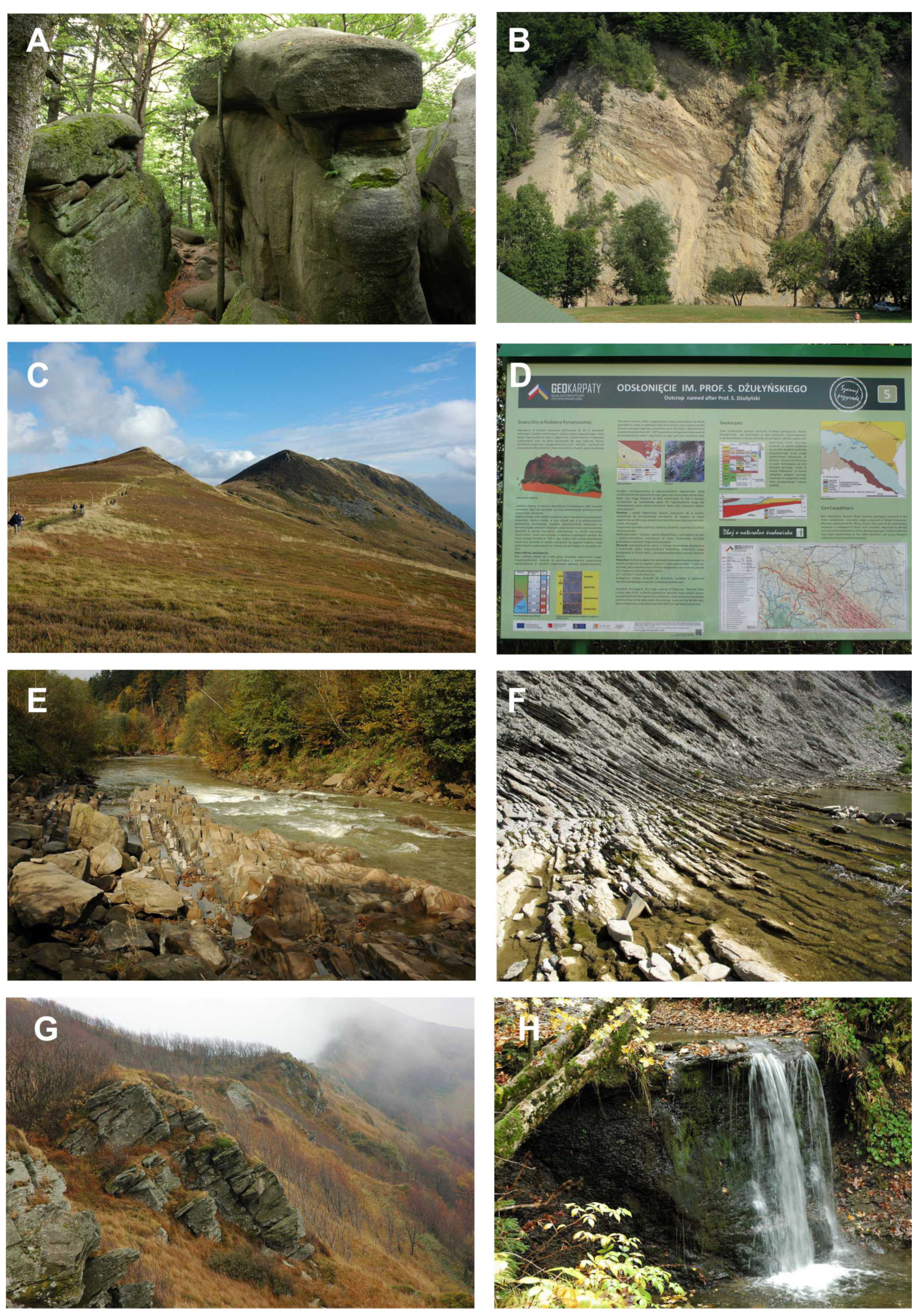

In the Bieszczady Wysokie Mountains, the natural environment assets are more valuable, which is confirmed by the fact that the most valuable areas are covered by the highest form of legal protection, i.e., national park. It is also an area of international rank—the East Carpathians Transboundary Biosphere Reserve. Therefore, further development of the accommodation and catering infrastructure should be planned very carefully so that it does not have a negative impact on the natural environment and landscape. The development of geotourism is most appropriate here. Alongside geomorphological processes and hydrologic phenomena, traces of oil exploitation can also be observed. This peripheral area has a deficient technical infrastructure and major socio-economic problems.

In the Wisłok Valley, on the other hand, in addition to the abiotic assets—numerous rock forms, rocky outcrops and hydrologic phenomena—it is possible to observe oil exploitation facilities and remnants of oil processing facilities. The area is unique on a global scale. However, it requires very extensive marketing actions and the preparation of tourist infrastructure for various groups of visitors. The tourist traffic has been small to date, there is a lack of accommodation, catering and accompanying infrastructure. The poor promotion of the assets and tourist attractions in the immediate vicinity is also a serious problem. The location and resources of the area provide a basis for preparing a very diverse offer, including geotourism. According to clustering, the Frysztak district emerges as an area with a high level of geotourism potential and other kinds of potential, hence this district should be included in the geopark.

Table 7.

SWOT analysis of natural and cultural resources, tourist development and socio-economic potential of the districts within the potential geopark in the Bieszczady Wysokie Mountains.

Table 7.

SWOT analysis of natural and cultural resources, tourist development and socio-economic potential of the districts within the potential geopark in the Bieszczady Wysokie Mountains.

| Internal Factors | External Factors |

|---|

| Strengths | Weaknesses | Opportunities | Threats |

|---|

| Geopark in the Bieszczady Wysokie Mountains |

| Districts: Czarna (r), Solina (r), Cisna (r), Komańcza (r), Baligród (r), Zagórz (u-r), Lutowiska (r) |

| Geoheritage |

− Valuable abiotic assets of the Bieszczady National Park − Inanimate nature reserves: Gołoborze, Zwiezło, Kamień nad Rzepedzią − Landscape reserves with valuable abiotic assets: Sine Wiry, Krywe, Źródliska Jasiołki, Przełom Osławy pod Duszatynem, Przełom Osławy pod Mokrem, Koziniec, − Monument of inanimate nature (rocky outcrops, rock forms, waterfalls, springs) − Numerous rocky outcrops − Varied landforms documenting diverse geological processes − Natural seepage of crude oil and methane

| − Natural secondary succession of vegetation that obstructs the view of sites with abiotic assets − Illegal quarrying of rocks − Taking over of former quarry sites for storage functions

| − Expanding the list of abiotic sites and sites under legal protection − Increased interest in geotourism − Broad promotion of the abiotic assets of an area

| |

| Animate nature |

− Bieszczady National Park (East Carpathians Biosphere Reserve) − Nature reserves, Natura 2000 areas − Very valuable natural assets (protected plant and animal species) − High degree of secondary naturalisation of the natural environment − Protection plan for the Cisna-Wetlina LP in force

| − Protection plan for the Bieszczady National Park and San Valley LP are not in force − Damage to flora and fauna − Inappropriate forest management − Pressure of residential housing

| − Inclusion of the primeval beech forests in the Bieszczady National Park in the UNESCO World Heritage List − Expanding the area of the East Carpathians Trasnboundary Biosphere Reserve − Increased interest in nature and cognitive tourism

| − Less funding for national parks and landscape parks to carry out conservation tasks − Competition from other areas − Lack of interest among tourists in the area’s natural environment assets − Exceeding the tourism absorption limit

|

| Cultural resources |

− Tserkvas in Turzańsk and Smolnik (UNESCO World Heritage List) − Traces of the Lemko and Boyko culture − Unique cultural landscape − Numerous historic religious and secular buildings (including wooden ones) of many different types − Multi-cultural heritage − Creative work of local artists and intangible culture

| − Poor state of repair of some sites/facilities − Difficult access to sites/facilities (e.g., in the resettled villages)

| − Inscribing more of the most valuable sites (wooden tserkvas) in the UNESCO World Heritage List − Establishing new forms of conservation: monuments of history and cultural parks − Broader institutional support for revitalisation − Broader use of external funding

| |

| Tourist development |

| − Highly seasonal accommodation offer − A high proportion of holiday centres catering to organised groups − Underdeveloped recreational facilities in some localities − Poor road capacity

| − Acquisition of external funding for the expansion of the accommodation and catering facilities − Better cooperation among districts − Attracting foreign tourists

| − Competitive offer of neighbouring areas − Mass tourism − Exceeding the area’s tourism absorption and trail capacity − Strong pressure of summer housing

|

| Socio-economic situation |

− Very low level of urbanisation − Strong interest of local governments in tourism development − Potential for ecological farming (livestock breeding)

| − Low population density − Demographic problems: negative migration rate, ageing population − Low economic potential − High unemployment − Financial problems of local governments − Inadequate spatial policy

| | |

Table 8.

SWOT analysis of natural and cultural resources, tourist development and socio-economic potential of the districts within the potential geoparks. Wisłok Valley—the Polish Texas Geopark.

Table 8.

SWOT analysis of natural and cultural resources, tourist development and socio-economic potential of the districts within the potential geoparks. Wisłok Valley—the Polish Texas Geopark.

| Internal Factors | External Factors |

|---|

| Strengths | Weaknesses | Opportunities | Threats |

|---|

| Geoheritage |

− Valuable abiotic assets of the Magura National Park − Inanimate nature reserves: “Prządki” − Landscape reserve with valuable abiotic assets: Kamień nad Jaśliskami − Numerous monument of inanimate nature (springs, rock forms, waterfall) and documentation sites − Numerous valuable rocky outcrops and rock forms − Mineral waters − Diverse land relief

| − Natural secondary succession of vegetation that obstructs the view of sites with abiotic assets − Poor accessibility of some sites/facilities − Illegal quarrying of rocks − Taking over of former quarry sites for storage functions

| − Expanding the list of abiotic sites and sites under legal protection − Increased interest in geotourism − Broad promotion of the abiotic assets of an area

| − Damage to geosites not covered by legal protection − Competition from other areas − Lack of interest in geological heritage

|

| Animate nature |

− Nature reserves, Natura 2000 areas − Protection plan for the Jaśliska LP in force − Plant and animal species under protection − High proportion of forests in some districts − High proportion of areas with valuable landscapes

| − Protection plan for the Czarnorzeki-Strzyżów LP is not in force − Damage to flora and fauna − Inappropriate forest management − Pressure of residential housing

| | |

| Cultural resources |

− Churches in Blizne and Haczów (UNESCO World Heritage List) − Monument of history (mine in Bóbrka) − Cultural park (Old Town Hill in Krosno) − Kamieniec castle in Odrzykoń − Health resort architecture complex in Iwonicz-Zdrój − Very high diversity of monuments in terms of their function − Traces of crude oil exploitation and oil-processing facilities

| | | |

| Tourist development |

| − Underdeveloped accommodation facilities − Lack of high-standard accommodation facilities − Lack of tourist information − Underdeveloped accompanying infrastructure

| | − Competitive offer of neighbouring areas − Lack of external support − Pressure of summer housing − Excessive pressure of quasi-health resort infrastructure

|

| Socio-economic situation |

− Health resort, spa and wellness treatments − Low level of urbanisation in some districts − High proportion of agriculturally used areas − Extensive farming, potential for viticulture

| − Low level of provision of water supply and sewage infrastructure − High unemployment rate in some districts − Inadequate spatial policy − Low level of interest among residents and local authorities in tourism development − Suburbanisation processes

| | − Lack of funds to support local entrepreneurship, including tourism economy − Development of branches of the economy which may have a negative impact on the natural environment and landscape

|

The establishment of the Turnica National Park would be an important impulse for the development of geotourism in the Podkarpackie Province. Efforts for its establishment have been undertaken for 35 years. The park would be located within the Wiar river catchment (districts of Ustrzyki Dolne, Fredropol, Bircza). As Kotlarczyk observes (2018, p. 92) [

74],

“The exceptional value of the area arises from its geological position and geographical location, morphology, geological structure and history of inanimate nature processes, and zones of minimum transformations of the original crust surface as well as from the diverse landscape of high aesthetic value.” The area features many outcrops where geological phenomena unique on the scale of the Carpathians can be observed: interesting stratotypes, rich macrofauna sites, rocks of organic, chemical and diagenetic origin, diverse forms of sedimentation in an oceanic basin. The establishment of such a park would certainly stimulate tourist traffic in the Pogórze Przemyskie Landscape Park and San Valley Landscape Park located on either side. It would also make it possible to prepare an extensive tourist offer for different target groups. An area with high abiotic environment assets that would consist of a mosaic of three national parks with five landscape parks would undoubtedly enable the preparation of geotourist products of diverse aesthetic, scientific and educational value. Such a network of areas with different conservation regimes, encompassing sites of diverse value and origin, could function very well. The preparation of a geotourist offer adapted to the individual potential and assets in the proposed geoparks in the Bieszczady Wysokie Mountains and the Wisłok Valley—the Polish Texas, taking into account the limitations in use and the need to protect inanimate and animate nature, offers the possibility of designating zones with the tourist function. At the same time, it makes it possible to achieve the goal of establishing a geopark i.e., sustainable socio-economic development. Perhaps in the future, after the new national park is established, extending the Bieszczady Geopark to include the Słonne Mountains Landscape Park should be considered.

Institutional support for the districts within which the geoparks would operate should be another step. Local government, tourism-related businesses and residents need to get involved. The local community should be convinced about the need to establish the geopark and about the potential benefits from it. Then, the community should be actively involved in the preparation of the master plan and its implementation. As the history of the establishment of geoparks in Poland shows, the most difficult stage is setting up a robust association of districts that carries out successive tasks and stimulates sustainable economic development. It seems that the biggest challenges are the lack of formal regulations (legal provisions, methodology guides) and financial support. As examples of Local Action Groups show, the cooperation between districts—also based on the tourism potential of a given area—can be fruitful. The experience of such Local Action Groups should be used when organising geoparks. Several such groups operate in the study area, e.g., “Kraina Nafty” (“Land of Oil”) or “Zielone Bieszczady” (“The Green Bieszczady”).

Persuading the local community to get involved in the process of establishing geoparks and then their operation is a major task. Residents have to be made aware that the “geopark” brand can help develop the tourist function and thus mitigate the unfavourable socio-economic phenomena occurring in the area. Demographic problems, particularly depopulation resulting from the negative migration rate and an ageing population, are of fundamental importance. The highest population density occurs in the districts of the Czarnorzeki-Strzyżów LP, while it is significantly lower in the other districts, which results from the resettlements in the past (Operation Vistula). In the peripheral rural districts, there is a high proportion of registered unemployed in the working age population; it is the highest in the districts of Cisna (14.1%), Solina (13.1%), and the lowest in the district of Rymanów (1.9%) [

55]. The lack of jobs is linked to the small number of businesses operating in the area. Owing to the socio-economic situation and the low efficacy of local governments in attracting investors, districts have low levels of revenue.

The districts within the landscape parks under study have to resolve various conflicts of the functions, needs of local communities and economic development. Investment projects implemented in the inhabited space not only improve the quality of life for the local community, but also contribute to enhancing the attractiveness of localities (regeneration of public space, improvement of the quality of health resort space, development of infrastructure related to environmental protection and improvement of transport links). At the same time, the proportion of areas with residential housing and service establishments has been allowed to increase in many districts, which has intensified the suburbanisation processes and led to the deterioration of the landscape assets. When preparing new areas for the development of business operations which are not always neutral to the condition of the natural environment, it is absolutely essential to consider the environmental determinants. The fundamental planning instrument enabling the appropriate management of space, including tourist space, is the local spatial development plan which specifies the rules for the spatial development and functions of a given area. It also provides the basis for safeguarding spatial order. In cases in which a local plan does not exist, the so-called decisions on development conditions and land management are issued for a specific area, or sometimes even for individual plots, but they do not ensure sufficient protection of space [

75]. Among the districts under study, only two—Dukla and Krościenko Wyżne—are fully covered by local plans, while in the case another two—Jaśliska and Krosno—just over half of their territory is covered. In 59% of the districts, less than 5% of their territory is covered by local plans [

55]. This indicates a very high threat to the spatial order, landscape and nature, particularly in the context of strong pressure of the development of single-family housing and tourist infrastructure. The main threat to the area is the propagation of various kinds of residential and tourist housing, including summer houses, service establishments and health resort treatment facilities, accompanied by the expansion of the access road network. While this increases the accessibility of the area, it can contribute to the development of mass-scale tourism in areas with valuable natural assets. Sustainable development in the districts, safeguarding the environmental balance and mitigating conflicts and preservation of the spatial order are possible only when spatial policy is conducted properly.