Characteristics and Use Patterns of Outdoor Recreationists on Public Lands in Alabama—Case Study of Bankhead National Forest and Sipsey Wilderness Area

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

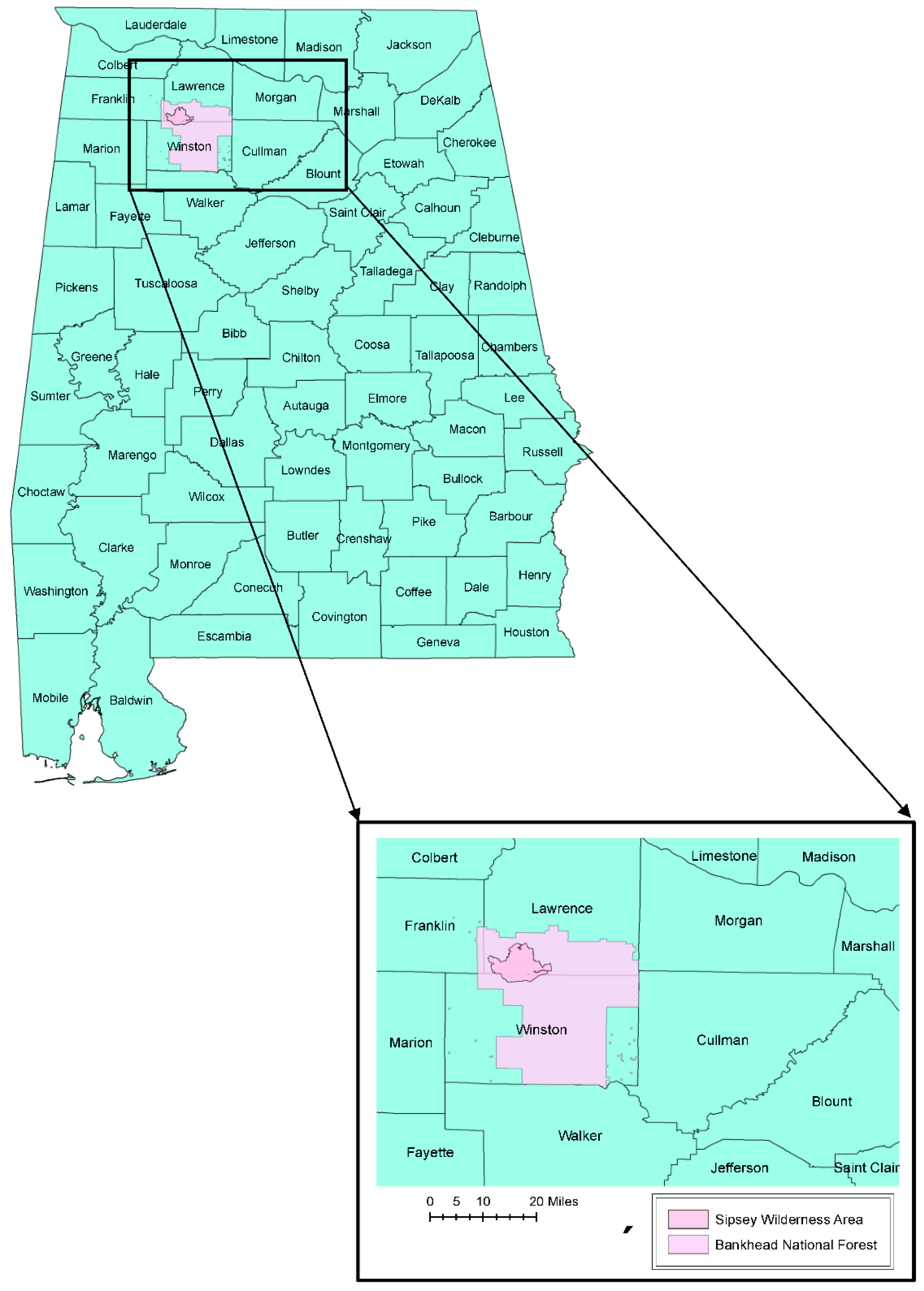

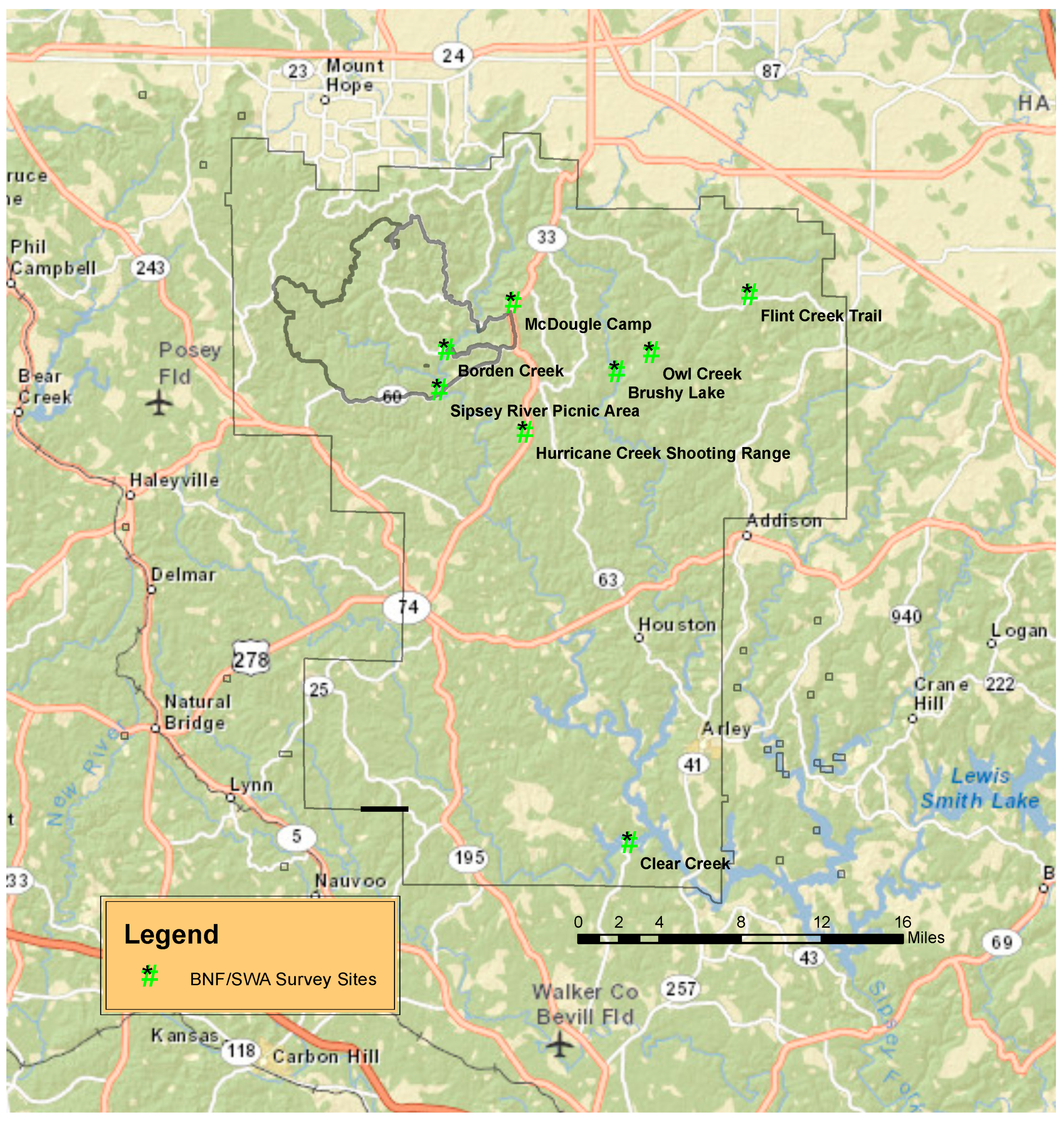

2.1. The Study Site

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results and Discussions

3.1. Racial/Ethnic Composition of Visitors and Their Preferred Activities

3.2. Visiting Group Patterns

3.3. Age Ranges of Visitors to BNF/SWA

3.4. Racial/ethnic Mix of Residents of Adjacent Counties

3.5. Visitor Use Patterns

3.6. The Need to Promote More Diversity of Participants and Users of the BNF/SWA

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Collins, S.; Brown, H. The Growing Challenge of Managing Outdoor Recreation. J. For. 2007, 105, 371–376. [Google Scholar]

- Ghimire, R.; Green, G.T.; Poudyal, N.C.; Cordell, H.K. An analysis of Perceived Constraints to Outdoor Recreation. J. Park Recreat. Adm. 2014, 32, 52–67. [Google Scholar]

- The Outdoor Foundation. Outdoor Participation Report. 2014. Available online: http://www.outdoorfoundation.org/research.participation.2014 (accessed on 20 August 2020).

- The Outdoor Foundation. 2021 Outdoor Participation Trends Report. Available online: https://outdoorindustry.org/resource/2021-outdoor-participation-trends-report/ (accessed on 19 December 2021).

- Johnson, C.Y.; Bowker, J.M. On-Site Wildland Activity Choices among African Americans and White Americans in the Rural South: Implications for Management. J. Park Recreat. Adm. 1999, 17, 21–39. [Google Scholar]

- Gobster, P.H. Managing Urban Parks for a Racially and Ethnically Diverse Clientele. Leis. Sci. 2002, 24, 143–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, N.S. Ethnic Minority Visitor Use and Non-Use of Parks and Participation in Natural Resources, Environmental Activities, and Outdoor Recreation. Breaking the Color Barrier in the Great American Outdoors. San Francisco State University. 2009. Available online: http://online.sfsu.edu/nroberts/Publications.html (accessed on 20 August 2020).

- Alabama Tourism Department. Sweet Home Alabama: Travel Economic Impact. 2014. Available online: http://tourism.alabama.gov/reports/ (accessed on 20 August 2021).

- Alabama Black Belt Adventures Association. Alabama’s Black Belt Region: A Powerful Force for Alabama’s Economy. 2012. Available online: http://media.al.com/businessnews/other/Black%20Belt%20report.pdf (accessed on 20 August 2020).

- Floyd, M.F. Managing National Parks in a Multicultural Society: Searching for Common Ground. Georg. Wright Forum 2001, 21, 41–51. [Google Scholar]

- Cordell, H.K.; Tarrant, M.A. Forest-based Outdoor Recreation. In Southern Forest Resource Assessment; Wear, D.N., Greis, J.G., Eds.; Southern Research Station, USDA Forest Service: Asheville, NC, USA, 2002; pp. 269–280. [Google Scholar]

- Lucas, R.C. Visitor Characteristics, Attitudes, and Use Patterns in Bob Marshall Wilderness Complex, 1970–1982; Research Paper INT-345; U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Intermountain Research Station: Ogden, UT, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Dillman, D.A. Mail and Telephone Surveys: A Total Design Method; John Wiley and Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Dillman, D.A. Mail and Internet Surveys: The Tailored Design Method, 2nd ed.; John Wiley and Sons: New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Scott, D.; Lee, K.J.J. People of Color and Their Constraints to National Parks Visitation. Georg. Wright Forum 2018, 35, 73–82. [Google Scholar]

- Sisneros-Kidd, A.M.; D’Antonio, A.; Monz, C.; Mitrovich, M. Improving understanding and management of the complex relationship between visitor motivations and spatial behaviors in parks and protected areas. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 280, 111841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christian, C.S.; Lacher, T.E., Jr.; Hammitt, W.E.; Potts, T.D. Visitation Patterns and Perceptions of National Park Users–Case Study of Dominica, West Indies. Caribb. Stud. 2009, 37, 83–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blankenbaker, R. A Solution to Budgets That Cut School Field Trips: Budget Woes Spark Techno-Ingenuity. Southeast Education Network. 2011. Available online: http://www.seenmagazine.us/articles/article-detail/articleid/1828/a-solution-to-budgets-that-cut-school-field-trips.aspx (accessed on 20 September 2020).

- Carter, E.W.; Boehm, T.L. Religious and Spiritual Expressions of Young People with Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities. Res. Pract. Pers. Disabil. 2019, 44, 37–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alabama Commission on Higher Education. Institutions of Higher Education. 2015. Available online: http://www.ache.state.al.us/Content/CollegesUniversities/AlaInstitutionMap.aspx (accessed on 19 September 2020).

- National Center for Education Statistics. 2015. Available online: http://high-schools.com/directory/al/counties/ (accessed on 16 September 2021).

- McAvoy, L.; Shirilla, P.; Flood, J. American Indian Gathering and Recreation Uses of National Forests. In Proceedings of the 2004 Northeastern Recreation Research Symposium, Bolton Landing, NY, USA, 28–30 March 2004; pp. 81–87. [Google Scholar]

- Booth, J.E.; Gaston, K.J.; Armsworth, P.A. Who benefits from the recreational use of protected areas? Ecol. Soc. 2010, 15, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United States Census. 2010 Interactive Population Search. U.S. Census Bureau. 2010. Available online: http://www.census.gov/2010census/popmap/ (accessed on 18 September 2020).

- Burns, R.; Graefe, A. Racial/Ethnic Minority Focus Group Interviews: Oregon SCORP; Division of Forestry and Natural Resources Recreation, West Virginia University: Morgantown, WV, USA, 2006; Available online: https://digital.osl.state.or.us/islandora/object/osl%3A708465/datastream/OBJ/view (accessed on 18 September 2020).

- Metcalf, E.C.; Burns, R.C.; Graefe, A.R. Understanding non-traditional forest recreation: The role of constraints and negotiation strategies among racial and ethnic minorities. J. Outdoor Recreat. Tour. 2013, 1, 29–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alabama Gazetteer. Available online: https://alabama.hometownlocator.com/features/cultural,class,church,scfips,01079.cfm (accessed on 18 February 2022).

- Bustam, T.D.; Thapa, B.; Buta, N. Demographic Differences within Race/Ethnicity Group Constraints to Outdoor Recreation Participation. J. Park Recreat. Adm. 2011, 22, 53–71. [Google Scholar]

- Winter, P.L.; Crano, W.D.; Basanez, T.; Lamb, C.S. Equity in Access to Outdoor Recreation–Informing a Sustainable Future. Sustain. J. 2020, 12, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| Racial Group | Number of Visitors | Percentage of Total Visitors (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Caucasian | 206 | 90.7 |

| American Indian/Alaskan Native | 11 | 4.8 |

| Asian | 3 | 1.3 |

| African American | 2 | 0.9 |

| Missing Information. | 5 | 2.2 |

| Ethnicity | Number of Visitors | Percentage of Total Visitors (%) |

|---|---|---|

| American Indian | 69 | 30.4 |

| Multiple Ethnicities | 39 | 17.2 |

| Irish | 17 | 7.5 |

| German | 14 | 6.2 |

| British | 7 | 3.1 |

| African American | 2 | 0.9 |

| Italian | 2 | 0.9 |

| Counties | # High Schools | # Community Colleges | # 4-Year Institutions | # Churches |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lawrence | 13 | 0 | 0 | 107 |

| Winston | 9 | 0 | 0 | 92 |

| Franklin | 9 | 1 | 0 | 139 |

| Walker | 25 | 1 | 0 | 239 |

| Cullman | 26 | 1 | 0 | 250 |

| Morgan | 30 | 0 | 0 | 208 |

| Marion | 9 | 1 | 0 | 141 |

| Totals | 121 | 4 | 0 | 1176 |

| County | Total County Population | Race/Ethnicity | Percentage of Total Population (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lawrence | 34,339 | African American | 11.5 |

| Asian | 0.1 | ||

| American Indian/Native American | 5.7 | ||

| Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander | 0.02 | ||

| Winston | 24,484 | African American | 0.5 |

| Asian | 0.2 | ||

| American Indian/Native American | 0.7 | ||

| Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander | 0.1 | ||

| Franklin | 31,703 | African American | 3.9 |

| Asian | 0.2 | ||

| American Indian/Native American | 0.7 | ||

| Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander | 0.03 | ||

| Walker | 67,023 | African American | 5.8 |

| Asian | 0.3 | ||

| American Indian/Native American | 0.4 | ||

| Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander | 0.05 | ||

| Cullman | 80,406 | African American | 1.1 |

| Asian | 0.4 | ||

| American Indian/Native American | 0.5 | ||

| Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander | 0.02 | ||

| Marion | 30,776 | African American | 3.5 |

| Asian | 0.2 | ||

| American Indian/Native American | 0.3 | ||

| Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander | 0.05 | ||

| Morgan | 119,490 | African American | 11.9 |

| Asian | 0.6 | ||

| American Indian/Native American | 0.9 | ||

| Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander | 0.09 |

| Outdoor Recreation/Leisure Activities | Level of Participation | Dominant Age Groups | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| # of Participants | % Total | Age Group(s) | # (%) of Total | |

| Camping | 66 | 21.9 | 40–49 | 19 (18.4) |

| Canoeing | 14 | 6.2 | 50–59 | 4 (1.8) |

| 20–29 | 4 (1.8) | |||

| Swimming | 41 | 18.1 | 20–29 | 9 (4.0) |

| Hunting | 14 | 6.2 | 40–49 | 9 (4.0) |

| Hiking | 90 | 39.6 | 30–39 | 22 (9.7) |

| Relaxation | 82 | 36.1 | 50–59 | 18 (7.9) |

| Kayaking | 10 | 4.4 | 50–59 | 5 (2.2) |

| Picnicking | 53 | 23.3 | 30–39 | 17 (7.5) |

| Fishing | 33 | 14.5 | 40–49 | 10 (4.4) |

| Sight Seeing | 60 | 26.4 | 30–39 | 19 (8.4) |

| Birding | 8 | 3.5 | 40–49 | 3 (1.3) |

| Horseback Riding | 51 | 22.5 | 50–59 | 17 (7.5) |

| Backpacking | 18 | 7.9 | 20–29 | 4 (1.8) |

| 30–39 | 4 (1.8) | |||

| 40–49 | 4 (1.8) | |||

| Other Activities | 54 | 23.9 | 50–59 | 15 (6.6) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Christian, C.S.; Scott, C.N. Characteristics and Use Patterns of Outdoor Recreationists on Public Lands in Alabama—Case Study of Bankhead National Forest and Sipsey Wilderness Area. Resources 2022, 11, 26. https://doi.org/10.3390/resources11030026

Christian CS, Scott CN. Characteristics and Use Patterns of Outdoor Recreationists on Public Lands in Alabama—Case Study of Bankhead National Forest and Sipsey Wilderness Area. Resources. 2022; 11(3):26. https://doi.org/10.3390/resources11030026

Chicago/Turabian StyleChristian, Colmore S., and Chelsea N. Scott. 2022. "Characteristics and Use Patterns of Outdoor Recreationists on Public Lands in Alabama—Case Study of Bankhead National Forest and Sipsey Wilderness Area" Resources 11, no. 3: 26. https://doi.org/10.3390/resources11030026