Corporate Social Responsibility in the Telecommunication Industry—Driver of Entrepreneurship

Abstract

1. Introduction

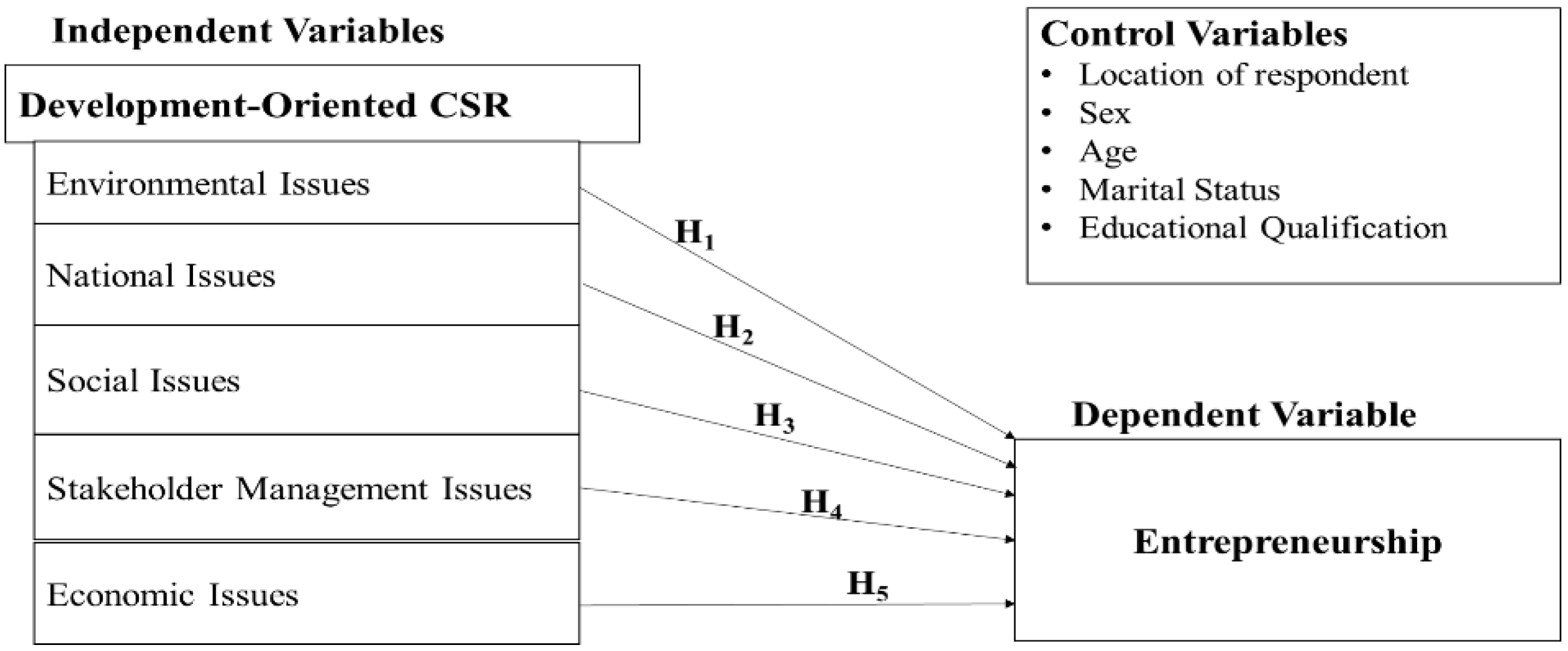

2. Literature Review

2.1. Theoretical Framework

2.2. Relationship between CSR and Environmental Issues

2.3. Relationship between CSR and National Issues

2.4. Relationship between CSR and Social Issues

2.5. Relationship between CSR and Stakeholder Management

2.6. Relationship between CSR and Economic Issues

3. Methodology

3.1. Research Design, Population, and Sample

3.2. Reliability, Validity, and Measurement of Variables

3.3. Demographics of the Respondents

4. Results

4.1. Respondents’ Perception of CSR

4.2. Respondents’ Perception of Entrepreneurship

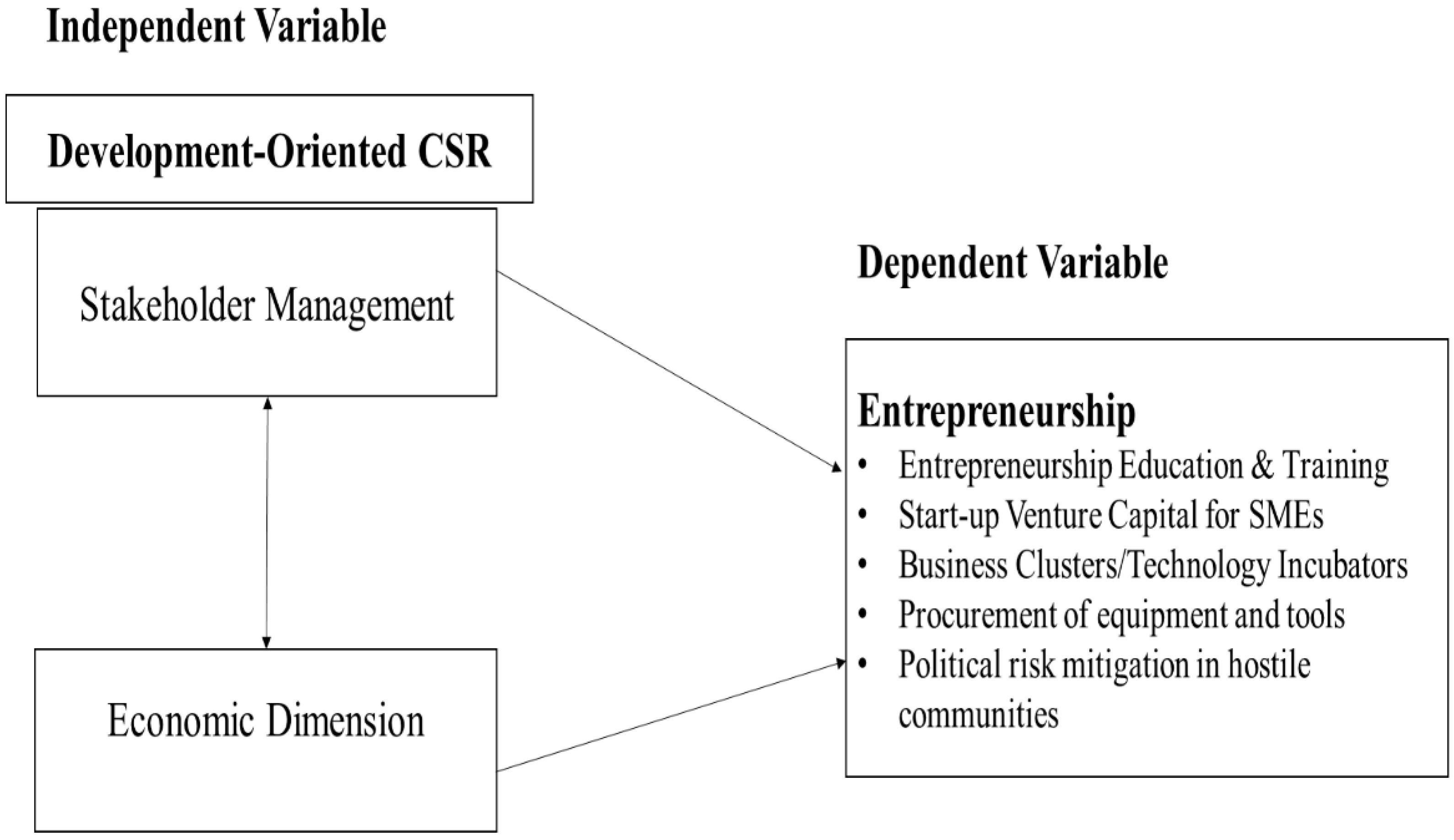

4.3. Development Potential of the CSR–Entrepreneurship Nexus

4.4. The Results of Testing the Development-Oriented CSR–Entrepreneurship Model Using Linear Regression Analysis

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

6.1. Theoretical and Practical Implications

6.2. Limitation and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Mean Rank | |

|---|---|

| Nigerian telecommunication companies provide business support for their suppliers and retail outlets. | 4.07 |

| The companies provide intervention for suppliers and retail outlets for growth of their clients’ revenue base. | 3.54 |

| The companies support the small and medium enterprises (SMEs) working with them for self-reliance and independence. | 3.46 |

| Support interventions are provided by the telecommunication companies to the small businesses for the purpose of building their technical skills. | 3.20 |

| Telecommunication companies provide support for host community to elicit their collaboration for business of peace. | 3.40 |

| Trainings and knowledge sharing are offered by telecommunication companies to small businesses and suppliers to boost their marketing and management skills. | 3.32 |

| Environmental Issues | Mean Rank |

|---|---|

| Telecommunication companies have environmental management policy on waste reduction and control. | 4.16 |

| These companies monitor the effluent (dangerous liquid chemicals) arising from the generating sets installed in residential locations. | 3.40 |

| They are proactive in the disposal of paper and polythene wastes arising from their recharge cards and packaging of other products. | 3.06 |

| Telecommunication companies ensure clean and green environment by recycling their recharge card wastes. | 2.80 |

| Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) is considered by the telecommunication companies when installing their transmission masts and generating sets in residential locations. | 3.91 |

| Telecommunication companies consider environmental impact of wastes and pollutants when developing new products/services. | 3.68 |

| Community and National Issues | Mean Rank |

|---|---|

| Telecommunication companies donate to charity bodies, clinics, and schools in their host communities. | 5.65 |

| They involve their employees in volunteering works and projects in the host communities. | 4.35 |

| They support poverty reduction programmes in their host communities and the society at large. | 4.60 |

| The companies have purchasing policies that favour local suppliers and small businesses in the host communities. | 4.10 |

| They have recruitment policies that favour the host communities where they operate. | 3.96 |

| They support aspects of the millennium development goals (MDGs) like poverty, health, and education for economic development. | 4.96 |

| The telecommunication companies extend their CSR to provide amenities for the disadvantaged Nigerians in both rural and urban communities. | 4.06 |

| The telecommunication companies extend their CSR to support eradication of deadly diseases including malaria and HIV/AIDS. | 4.32 |

| Social Issues | Mean Rank |

|---|---|

| Nigerian Telecommunication companies get involved in academic and education programmes. | 4.01 |

| They facilitate specialised education and training to increase society’s literacy level. | 3.17 |

| They support educational projects like building classroom blocks, libraries, workshops, and laboratories. | 3.22 |

| Telecommunication companies provide scholarships to indigent and brilliant students in the formal school system. | 3.61 |

| Telecommunication companies support women empowerment and widow issues. | 2.68 |

| Telecommunication companies provide sponsorship for different aspects of sports development. | 4.31 |

| Economic Issues | Mean Rank |

|---|---|

| Telecommunication companies adopt CSR with passion for the benefit of tax reduction or exemption from the government. | 3.03 |

| CSR participation of telecommunication companies promotes the strategic business interest of long run profitability. | 3.59 |

| The CSR programmes boost corporate reputation of these companies in the eyes of government and the public. | 3.94 |

| Telecommunication companies adopt CSR as a social investment for creating shared value with their suppliers and small business owners. | 3.24 |

| The CSR programmes are adopted for the benefits of revenues and costs optimisation. | 3.32 |

| Telecommunication companies adopt CSR to increase customer brand loyalty and market rating. | 3.89 |

| Stakeholder Engagement | Mean Rank |

|---|---|

| Telecommunication companies in Nigeria have in place a mechanism for stakeholder engagement. | 4.01 |

| The most valuable stakeholders to these companies are shareholders, regulators, governments, and investors. | 4.30 |

| Engagement with stakeholders is influenced by pressure from host communities, human rights groups, and customers. | 4.29 |

| The stakeholder engagement of these companies is a consensus-building process between the companies and their stakeholders. | 4.03 |

| The stakeholder engagement of the telecommunication companies is frequent, regular, and known to all parties concerned. | 3.13 |

| CSR programmes and projects are provided based on outcome of engagement with the stakeholders as end-users in the host community. | 3.54 |

| The stakeholder engagement in CSR activities is driven by strategic business interests of the telecommunication companies. | 4.71 |

References

- Ciutacu, C.; Chivu, L.; Preda, D. Company’S Social Responsibility-A Challenge for Contemporary World. Rom. J. Econ. 2005, 20, 79–94. [Google Scholar]

- Gherghina, S.C.; Vintila, G. Exploring the impact of corporate social responsibility policies on firm value: The case of listed companies in Romania. Econ. Sociol. 2016, 9, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brezoi, A.G. Ethics and corporate social responsibility in the current geopolitical context. Econ. Insights–Trends Chall. 2018, 7, 45–52. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, S.A.R.; Yu, Z.; Panait, M.; Janjua, L.R.; Shah, A. (Eds.) Global Corporate Social Responsibility Initiatives for Reluctant Businesses; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Ionescu, R. Corporate Social Responsibility Programs of the Bucharest Stock Exchange. Econ. Insights-Trends Chall. 2019, 8, 45–54. [Google Scholar]

- Brønn, P.S.; Vrioni, A.B. Corporate Social Responsibility and Cause Related Marketing: An Overview. Int. J. Advert. 2001, 20, 207–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweeney, L. A Study of Current Practice of Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) and an Examination of the Relationship between CSR and Financial Performance Using Structural Equation Modelling (SEM). Ph.D. Thesis, Dublin Institute of Technology, Dublin, Ireland, 2009. Available online: https://arrow.tudublin.ie/appadoc/19/ (accessed on 20 November 2021).

- Yekini, C.O. Corporate Community Involvement Disclosure: An Evaluation of the Motivation & Reality. Ph.D. Thesis, De Montfort University, Leicester, UK, 2012. Available online: https://www.dora.dmu.ac.uk/handle/2086/6910 (accessed on 20 November 2021).

- Raimi, L. Leveraging CSR as a ‘support-aid’ for triple bottom-line development in Nigeria: Evidence from the telecommunication industry. In Comparative Perspectives on Global Corporate Social Responsibility; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2017; pp. 208–225. [Google Scholar]

- Carroll, A.B. Corporate social responsibility: Evolution of a definitional construct. Bus. Soc. 1999, 38, 268–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, M. The social responsibility of business is to increase its profits. New York Times, 13 September 1970; 1–2. [Google Scholar]

- Samuelson, P.A. Love that corporation. Mountain Bell Magazine. In Corporate Social Responsibility—Evolution of a Definitional Construct; Carroll, A., Ed.; Business & Society; Sage Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1971; Volume 38, pp. 268–295. [Google Scholar]

- Kakabadse, N.K.; Rozuel, C.; Lee-Davies, L. Corporate social responsibility and stakeholder approach: A conceptual review. Int. J. Bus. Gov. Ethics 2005, 1, 277–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raimi, L. Entrepreneurship Development through Corporate Social Responsibility—A Study of the Nigerian Telecommunication Industry. Ph.D. Thesis, Leicester Business School, De Montfort University, Leicester, UK, 2015. Available online: https://dora.dmu.ac.uk/handle/2086/11163 (accessed on 22 February 2022).

- Jin, M.; Kim, B. The Effects of ESG Activity Recognition of Corporate Employees on Job Performance: The Case of South Korea. J. Risk Financ. Manag. 2022, 15, 316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Fetscherin, M.; Alon, I.; Lattemann, C.; Yeh, K. Corporate social responsibility in emerging markets. Manag. Int. Rev. 2010, 50, 635–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez, B.; Fornes, G. Corporate social responsibility in emerging markets: Case studies of Spanish MNCs in Latin America. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2015, 27, 214–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gigauri, I.; Vasilev, V. Corporate Social Responsibility in the Energy Sector: Towards Sustainability. In Energy Transition; Springer: Singapore, 2022; pp. 267–288. [Google Scholar]

- Fassin, Y.; Van Rossem, A. Corporate governance in the debate on CSR and ethics: Sensemaking of social issues in management by authorities and CEOs. Corp. Gov. Int. Rev. 2009, 17, 573–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamali, D.; Karam, C. CSR in developed versus developing countries: A comparative glimpse. In Research Handbook on Corporate Social Responsibility in Context; Edward Elgar Publishing: Northampton, MA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Svensson, G.; Ferro, C.; Høgevold, N.; Padin, C.; Varela, J.C.S.; Sarstedt, M. Framing the triple bottom line approach: Direct and mediation effects between economic, social and environmental elements. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 197, 972–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikram, M.; Sroufe, R.; Mohsin, M.; Solangi, Y.A.; Shah, S.Z.A.; Shahzad, F. Does CSR influence firm performance? A longitudinal study of SME sectors of Pakistan. J. Glob. Responsib. 2019, 11, 27–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahzad, M.; Qu, Y.; Javed, S.A.; Zafar, A.U.; Rehman, S.U. Relation of environment sustainability to CSR and green innovation: A case of Pakistani manufacturing industry. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 253, 119938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arslan, H.M.; Chengang, Y.; Siddique, M.; Yahya, Y. Influence of Senior Executives Characteristics on Corporate Environmental Disclosures: A Bibliometric Analysis. J. Risk Financ. Manag. 2022, 15, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latapí Agudelo, M.A.; Jóhannsdóttir, L.; Davídsdóttir, B. A literature review of the history and evolution of corporate social responsibility. Int. J. Corp. Soc. Responsib. 2019, 4, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamali, D.; Karam, C.; Blowfield, M. (Eds.) Development-Oriented Corporate Social Responsibility: Volume 2; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2015; 272p. [Google Scholar]

- Paulík, J.; Sobeková-Májková, M.; Tykva, T.; Červinka, M. Application of the CSR measuring model in commercial bank in relation to their financial performance. Econ. Sociol. 2015, 8, 65–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genasci, M.; Pray, S. Extracting accountability: The implications of the resource curse for CSR theory and practice. Yale Hum. Rts. Dev. 2008, 11, 37. [Google Scholar]

- Akhuemonkhan, I.A.; Raimi, L.; Ogunjirin, O.D. Corporate Social Responsibility and Entrepreneurship (CSRE): Antidotes to Poverty, Insecurity and Underdevelopment in Nigeria. Soc. Responsib. J. 2015, 11, 56–81. [Google Scholar]

- Idemudia, U. Corporate social responsibility and developing countries: Moving the critical CSR research agenda in Africa forwards. Prog. Dev. Stud. 2011, 11, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adelopo, I.; Yekini, K.; Raimi, L. Bridging the governance gap with political CSR. In Development-Oriented Corporate Social Responsibility; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2017; pp. 29–48. [Google Scholar]

- Egbeleke, A.A. Strategic corporate responsibility and sustainability performance management model. J. Mgmt. Sustain. 2014, 4, 92–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wushe, T. Corporate Community Engagement (CCE) in Zimbabwe’s Mining Industry from the Stakeholder Theory Perspective. Ph.D. Thesis, UNISA Institutional Repository, Pretoria, South Africa, 2014. Available online: https://uir.unisa.ac.za/handle/10500/14154 (accessed on 20 November 2021).

- Edward, P.; Willmott, H. Corporate citizenship: Rise or demise of a myth? Acad. Manag. Rev. 2008, 33, 771–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palazzo, G.; Scherer, A.G. Corporate social responsibility, democracy, and the politicization of the corporation. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2008, 33, 773–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scherer, A.G.; Rasche, A.; Palazzo, G.; Spicer, A. Managing for political corporate social responsibility: New challenges and directions for PCSR 2.0. J. Manag. Stud. 2016, 53, 273–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yap, N.T. CSR and the development deficit: Part of the solution or part of the problem? In Development-Oriented Corporate Social Responsibility; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2017; pp. 134–152. [Google Scholar]

- He, H.; Harris, L. The impact of Covid-19 pandemic on corporate social responsibility and marketing philosophy. J. Bus. Bus. Res. 2020, 116, 176–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siano, A.; Raimi, L.; Palazzo, M.; Panait, M.C. Mobile banking: An innovative solution for increasing financial inclusion in Sub-Saharan African Countries: Evidence from Nigeria. Sustainability 2020, 12, 10130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vida, I.; Spaller, E.; Vasa, L. Potential Effects of Finance 4.0 on the Employment in East Africa. Econ. Sociol. 2020, 29–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhigbe, J.O.; Olokoyo, F.O. Corporate Social Responsibility & Brand Loyalty in The Nigerian Telecommunication Industry. In IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science; IOP Publishing: Bristol, UK, 2019; Volume 331, p. 012063. [Google Scholar]

- Osemene, O.F. Corporate social responsibility practices in mobile telecommunications industry in Nigeria. Eur. J. Bus. Manag. 2012, 4, 149–159. [Google Scholar]

- Nsikan, J.E.; Umoh, V.A.; Bariate, M. Corporate Social Responsibility and Mobile Telecommunication Competitiveness in Nigeria: The Case of MTN Nigeria. Am. J. Ind. Bus. Manag. 2015, 5, 527–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Osagie, N.G. Corporate Social Responsibility and Profitability in Nigeria Telecommunication Industry: A Case Study of MTN Nigeria. J. Entrep. Manag. 2017, 6, 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Kotler, P.; Lee, N. Corporate Social Responsibility: Doing the Most Good for Your Company and Your Cause; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Dartey-Baah, K.; Amponsah-Tawiah, K. Exploring the limits of Western Corporate Social Responsibility Theories in Africa. Int. J. Bus. Soc. Sci. 2011, 2, 126–137. [Google Scholar]

- Navickas, V.; Kontautiene, R.; Stravinskiene, J.; Bilan, Y. Paradigm shift in the concept of corporate social responsibility: COVID-19. Green Financ. 2021, 3, 138–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klimek, D.; Jędrych, E. A model for the sustainable management of enterprise capital. Sustainability 2020, 13, 183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matei, M. Responsabilitatea Socială a Corporaţiilor şi Instituţiilor şi Dezvoltarea Durabilă a României; Expert Publishing House: Bucharest, Romania, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Jędrych, E.; Klimek, D.; Rzepka, A. Principles of Sustainable Management of Energy Companies: The Case of Poland. Energies 2021, 14, 2042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, J. The Business of Peace: Business as a Partner in Conflict Resolution; Prince of Wales Business Leaders Forum: London, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Mordi, C.; Opeyemi, I.S.; Tonbara, M.; Ojo, S. Corporate Social Responsibility and the Legal Regulation in Nigeria. Econ. Insights Trends Chall. 2012, 64, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Penrose, E. The Theory of the Growth of the Firm, Revised Edition; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1963. [Google Scholar]

- Sathorar, H.H. Assessing Entrepreneurship Education at Secondary Schools in the NMBM; Nelson Mandela Metropolitan University: Porth Elizabeth, South Africa, 2009; Available online: https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/145048301.pdf (accessed on 20 November 2021).

- Stevenson, H.H.; Jarillo, J.C. A paradigm of entrepreneurship: Entrepreneurial management. Strateg. Manag. J. 1990, 11, 17–27. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.L.; Chugh, H. Entrepreneurial learning: Past research and future challenges. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2014, 16, 24–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baert, C.; Meuleman, M.; Debruyne, M.; Wright, M. Portfolio entrepreneurship and resource orchestration. Strateg. Entrep. J. 2016, 10, 346–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welter, C.; Mauer, R.; Wuebker, R.J. Bridging behavioral models and theoretical concepts: Effectuation and bricolage in the opportunity creation framework. Strateg. Entrep. J. 2016, 10, 5–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Croitoru, G.; Duica, M.; Robescu, O.; Valentin, R.A.D.U.; Oprisan, O. Entrepreneurial resilience, factor of influence on the function of entrepreneur. Proc. RCE 2017, 193–216. [Google Scholar]

- Radu, V.; Cojocaru, M.; Dermengi, A.G. Determining Factors for Achieving Success in Entrepreneurship. LUMEN Proceedings 2021, 17, 131–140. [Google Scholar]

- He, B.; Li, Z.; Vinig, T. Entrepreneurship, technological progress and resource allocation efficiency: A case of China. J. Chin. Entrep. 2010, 2, 242–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J. Entrepreneurship, Social Capital and Governance: Directions for Sustainable Development and Competitiveness of Regions. J. Entrep. Emerg. Econ. 2014, 6, 196–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Ding, T.; Li, J. Entrepreneurship and economic development in China: Evidence from a time-varying parameters stochastic volatility vector autoregressive model. Technol. Anal. Strateg. Manag. 2015, 27, 660–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, G.; Borbora, S. Institutional environment differences and their application for entrepreneurship development in India. J. Entrep. Emerg. Econ. 2018, 11, 177–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, R.E.; Wicks, A.C.; Parmar, B. Stakeholder Theory and The Corporate Objective Revisited. Organ. Sci. 2004, 15, 364–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Secchi, D. Utilitarian, managerial and relational theories of corporate social responsibility. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2007, 9, 347–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, M. Corporate Social Responsibility and Its Role in Community Development: An International Perspective. J. Int. Soc. Res. 2009, 2, 199–209. [Google Scholar]

- Fontrodona, J.; Sison, A.J.G. The Nature of the firm, Agency Theory and Shareholder Theory: A critique from philosophical Anthropology. J. Bus. Ethics 2006, 66, 33–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, A.B.; Buchholtz, A.K. Business and Society: Ethics, Sustainability, and Stakeholder Management; Cengage Learning: Boston, MA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Fleischhauer, K.J. A Review of Human Capital Theory: Microeconomics. University of St. Gallen, Department of Economics Discussion Paper, (2007-01). 2007. Available online: http://ux-tauri.unisg.ch/RePEc/usg/dp2007/DP01_Fl.pdf (accessed on 15 November 2021).

- Becker, G. Human Capital: A Theoretical and Empirical Analysis with Special Reference to Education; The University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Becker, S.O.; Woessmann, L. The effects of the Protestant Reformation on human capital. In The Oxford Handbook of the Economics of Religion; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2011; pp. 93–110. [Google Scholar]

- Coşkun, H.E.; Popescu, C.; Şahin Samaraz, D.; Tabak, A.; Akkaya, B. Entrepreneurial University Concept Review from the Perspective of Academicians: A Mixed Method Research Analysis. Sustainability 2022, 14, 10110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultz, T.W. The Value of Ability to Deal with Disequilibria. J. Econ. Lit. 1975, 13, 827–846. [Google Scholar]

- Ladipo, M.K.; Akhuemonkhan, I.A.; Raimi, L. Technical Vocational Education and Training (TVET) as mechanism for Sustainable Development in Nigeria (SD): Potentials, Challenges and Policy Prescriptions. In Proceedings of the CAPA International Conference, Banjul, Gambia, 2–8 June 2013; pp. 3–8. [Google Scholar]

- Grigorescu, A.; Pelinescu, E.; Ion, A.E.; Dutcas, M.F. Human capital in digital economy: An empirical analysis of central and eastern European countries from the European Union. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grigorescu, A.; Mocanu, A. Teleworking perspectives for Romanian SMEs after the COVID-19 pandemic. Manag. Dyn. Knowl. Econ. 2020, 8, 383. [Google Scholar]

- Zhan, X.; Popescu, D.M.; Radu, V. Challenges for Romanian entrepreneurs in managing remote workers. LUMEN Proceedings 2020, 14, 670–687. [Google Scholar]

- Bălăcescu, A.; Pătraşcu, A.; Păunescu, L.M. Adaptability to Teleworking in European Countries. Amfiteatru Economic 2021, 23, 683–699. [Google Scholar]

- Turkes, M.C.; Căpus, S.; Topor, D.I.; Staras, A.I.; Hint, M.S.; Stoenica, L.F. Motivations for the Use of IoT Solutions by Company Managers in the Digital Age: A Romanian Case. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 6905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefan, D.; Vasile, V.; Oltean, A.; Comes, C.-A.; Stefan, A.-B.; Ciucan-Rusu, L.; Bunduchi, E.; Popa, M.-A.; Timus, M. Women Entrepreneurship and Sustainable Business Development: Key Findings from a SWOT–AHP Analysis. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, P.G.; Cook, M.L. TW Schultz and the human-capital approach to entrepreneurship. Rev. Agric. Econ. 2006, 28, 344–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weisbrod, B.A. Investing in human capital. J. Hum. Resour. 1966, 1, 5–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishikawa, M.; Ryan, D. Schooling, basic skills and economic outcomes. Econ. Educ. Rev. 2002, 21, 231–243. [Google Scholar]

- Carroll, A.B. The pyramid of corporate social responsibility: Toward the moral management of organisational stakeholders. Bus. Horiz. 1991, 34, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friends of the Earth. Media Briefing on Gas Flaring in Nigeria; Underwood: London, UK, 2004; Available online: http://www.foe.co.uk/sites/default/files/downloads/gasflaringinnigeria.pdf (accessed on 15 November 2021).

- Carroll, A.B. Carroll’s pyramid of CSR: Taking another look. Int. J. Corp. Soc. Responsib. 2016, 1, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Tong, L.; Takeuchi, R.; George, G. Corporate social responsibility: An overview and new research directions: Thematic issue on corporate social responsibility. Acad. Manag. J. 2016, 59, 534–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suganthi, L. Examining the relationship between corporate social responsibility, performance, employees’ pro-environmental behavior at work with green practices as mediator. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 232, 739–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, J. Impact of total quality management on corporate green performance through the mediating role of corporate social responsibility. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 242, 118458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fukuda, K.; Ouchida, Y. Corporate social responsibility (CSR) and the environment: Does CSR increase emissions? Energy Econ. 2020, 92, 104933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roome, N. Some implications of national agendas for CSR. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Across Eur. 2005, 317, 333. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson, J. CSR and Public Policy. New Forms of Engagement between Business and Government; Corporate Social Responsibility Initiative–Working Papers; Harvard University: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Halkos, G.; Skouloudis, A. National CSR and institutional conditions: An exploratory study. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 139, 1150–1156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKinsey & Company. Tackling Sociopolitical Issues in Hard Times: McKinsey Global Survey Results. 2009. Available online: https://www.mckinsey.com/featured-insights/leadership/tackling-sociopolitical-issues-in-hard-times-mckinsey-global-survey-results (accessed on 15 November 2021).

- Danziger, P.N. When Corporate Social Responsibility Veers into Political Action: Safe or Sorry? Forbes Publication, 12 March 2018. Available online: https://www.forbes.com/sites/pamdanziger/2018/03/12/when-corporate-social-responsibility-veers-into-political-action-safe-or-sorry/?sh=506134fc257d (accessed on 15 November 2021).

- Pies, I.; Beckmann, M.; Hielscher, S. The political role of the business firm: An ordonomic concept of corporate citizenship developed in comparison with the Aristotelian idea of individual citizenship. Bus. Soc. 2014, 53, 226–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirschhorn, N. Corporate social responsibility and the tobacco industry: Hope or hype? Tob. Control 2004, 13, 447–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Fooks, G.J.; Gilmore, A.B. Corporate philanthropy, political influence, and health policy. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e80864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vollero, A.; Siano, A.; Palazzo, M.; Elving, W. Corporate Communication and CSR; comparing Italian and Dutch energy companies on anti-greenwashing strategies. In Proceedings of the CSR Communication Conference 2011 (No. 1), Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 26–28 October 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Cesar, S. Corporate social responsibility fit helps to earn the social licence to operate in the mining industry. Resour. Policy 2020, 74, 101814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindman, Å.; Ranängen, H.; Kauppila, O. Guiding corporate social responsibility practice for social licence to operate: A Nordic mining perspective. Extr. Ind. Soc. 2020, 7, 892–907. [Google Scholar]

- Palazzo, G.; Richter, U. CSR business as usual? The case of the tobacco industry. J. Bus. Ethics 2005, 61, 387–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polonsky, M.J.; Jevons, C. Understanding issue complexity when building a socially responsible brand. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2006, 18, 340–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melyoki, L.L.; Kessy, F.L. Why companies fail to earn the social licence to operate?Insights from the extractive sector in Tanzania. J. Rural Community Dev. 2020, 15, 29–54. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, M. Sustainability as Stakeholder Management. In Business and Sustainability: Concepts, Strategies and Changes (Critical Studies on Corporate Responsibility, Governance and Sustainability, Vol. 3); Eweje, G., Perry, M., Eds.; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2011; pp. 221–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvioni, D.M.; Gennari, F. CSR, Sustainable Value Creation and Shareholder Relations. Symph. Emerg. Issues Manag. 2017, 1, 36–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnett, M.L.; Henriques, I.; Husted, B.W. Governing the Void between Stakeholder Management and Sustainability. In Sustainability, Stakeholder Governance, and Corporate Social Responsibility (Advances in Strategic Management, Vol. 38); Emerald Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2018; pp. 121–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, S. Corporate Partnerships for Entrepreneurship: Building the Ecosystem in the Middle East and Southeast Asia; Corporate Social Responsibility Initiative Working Paper No. 62; John F. Kennedy School of Government, Harvard University: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Porter, M.E.; Kramer, M.R. Creating Shared Value: How to reinvent capitalism—and unleash a wave of innovation and growth. Harv. Bus. Rev. HBR 2011, 89, 62–77. [Google Scholar]

- Cantrell, J.E.; Kyriazis, E.; Noble, G. Developing CSR giving as a dynamic capability for salient stakeholder management. J. Bus. Ethics 2015, 130, 403–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luetkenhorst, W. Corporate Social Responsibility and the Development Agenda The Case for Actively Involving Small and Medium Enterprises. Intereconomics 2004, 39, 157–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerr, J.E. Sustainability Meets Profitability: The Convenient Truth of How the Business Judgment Rule Protects a Board’s Decision to Engage in Social Entrepreneurship. Cardozo Law Rev. 2007, 29, 623–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frynas, J.G. The false developmental promise of corporate social responsibility: Evidence from multinational oil companies. Int. Aff. 2005, 81, 581–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frynas, J.G. Corporate social responsibility and international development: Critical assessment. Corp. Gov. Int. Rev. 2008, 16, 274–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S. On the Relationship between CSR and Profit. J. Int. Bus. Ethics 2014, 7, 51–57. [Google Scholar]

- Rivera, J.M.; Muñoz, M.J.; Moneva, J.M. Revisiting the relationship between corporate stakeholder commitment and social and financial performance. Sustain. Dev. 2017, 25, 482–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taskin, D. The relationship between CSR and banks’ financial performance: Evidence from Turkey. J. Yaşar Univ. 2015, 10, 21–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abou Fayad, A.; Ayoub, R.; Ayoub, M. Causal relationship between CSR and FB in banks. Arab Econ. Bus. J. 2017, 12, 93–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, S.J.; Chung, C.Y.; Young, J. Study on the Relationship between CSR and Financial Performance. Sustainability 2019, 11, 343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saunders, M.; Lewis, P.; Thornhill, A. Research Methods for Business Students, 7th ed.; Pearson Education: Harlow, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Halbritter, G.; Dorfleitner, G. The wages of social responsibility—Where are they? A critical review of ESG investing. Rev. Financ. Econ. 2015, 26, 25–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiba, S.; van Rijnsoever, F.J.; Hekkert, M.P. Firms with benefits: A systematic review of responsible entrepreneurship and corporate social responsibility literature. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2019, 26, 265–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheema, S.; Afsar, B.; Al-Ghazali, B.M.; Maqsoom, A. Retracted: How employee’s perceived corporate social responsibility affects employee’s pro-environmental behaviour? The influence of organisational identification, corporate entrepreneurship, and environmental consciousness. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2020, 27, 616–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Technology Times. Lagos State Has Most Active Phones, Internet Users in Nigeria. 2016. Available online: https://technologytimes.ng/surveylagos-tops-number-of-internet-users-and-active-voice-subscribers-in-nigeria/ (accessed on 20 November 2021).

- Telepoint Africa. 33% of Mobile Subscribers in Nigeria Dispersed across Only 5 States, FCT. 2016. Available online: https://techpoint.africa/2016 (accessed on 20 November 2021).

- Parten, M. Surveys, Polls, and Samples: Practical Procedures; Harper and Brothers: New York, NY, USA, 1950. [Google Scholar]

- Cresswell, J.W.; Plano Clark, V.L. Designing and Conducting Mixed Method Research, 2nd ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Palinkas, L.A.; Horwitz, S.M.; Green, C.A.; Wisdom, J.P.; Duan, N.; Hoagwood, K. Purposeful sampling for qualitative data collection and analysis in mixed method implementation research. Adm. Policy Ment. Health Ment. Health Serv. Res. 2015, 42, 533–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Etikan, I.; Musa, S.A.; Alkassim, R.S. Comparison of convenience sampling and purposive sampling. Am. J. Theor. Appl. Stat. 2016, 5, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amaeshi, K.M.; Adi, B.C.; Ogbechie, C.; Amao, O.O. Corporate Social Responsibility in Nigeria: Western Mimicry or Indigenous Influences? J. Corp. Citizsh. 2006, 24, 83–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kehbila, A.G.; Ertel, J.; Brent, A.C. Strategic corporate environmental management within the South African automotive industry: Motivations, benefits, hurdles. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2009, 16, 310–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uadiale, O.M.; Fagbemi, T.O. Corporate Social Responsibility and Financial Performance in Developing Economies: The Nigerian Experience. J. Econ. Sustain. Dev. 2012, 3, 44–54. [Google Scholar]

- Quince, T.; Whittaker, H. Entrepreneurial Orientation and Entrepreneurs’ Intentions and Objectives; Working Paper No. 271; ESRC Centre for Business Research, University of Cambridge: Cambridge, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.L. Entrepreneurial orientation, learning orientation, and firm performance. Entrep. Theory Pract. 2008, 32, 635–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.H.; Huang, J.W.; Tsai, M.T. Entrepreneurial orientation and firm performance: The role of knowledge creation process. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2009, 38, 440–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madhoushi, M.; Sadati, A.; Delavari, H.; Mehdivand, M.; Mihandost, R. Entrepreneurial Orientation and Innovation Performance: The Mediating Role of Knowledge Management. Asian J. Bus. Manag. 2011, 3, 310–316. [Google Scholar]

- Giannarakis, G. The determinants influencing the extent of CSR disclosure. Int. J. Law Manag. 2014, 56, 393–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Chen, S.; Shao, Y.; Gao, S. CSR and firm value: Evidence from China. Sustainability 2018, 10, 4597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, M. Does CSR influence M&A target choices? Financ. Res. Lett. 2019, 30, 153–159. [Google Scholar]

- Cronbach, L.J. Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika 1951, 16, 297–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, D.; Mallery, P. SPSS for Windows Step by Step: A Simple Guide and Reference, 4th ed.; 11.0 Update; Allyn & Bacon: Boston, MA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Field, A. Discovering Statistics Using SPSS for Windows; SAGE Publication: London, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Nathans, L.L.; Oswald, F.L.; Nimon, K. Interpreting multiple linear regression: A guidebook of variable importance. Pract. Assess. Res. Eval. 2012, 17, n9. [Google Scholar]

| Variable | Description | Frequency | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Location | Lagos 1 | 48 | 13.0% |

| Lagos 2 | 34 | 9.2% | |

| Lagos 3 | 93 | 25.2% | |

| Lagos 4 | 58 | 15.7% | |

| Lagos 5 | 32 | 8.7% | |

| Lagos 6 | 38 | 10.3% | |

| Lagos 7 | 20 | 5.4% | |

| Lagos 8 | 46 | 12.5% | |

| Total | 369 | 100% | |

| Sex | Male | 280 | 75.9% |

| Female | 89 | 24.1% | |

| Total | 369 | 100% | |

| Age | 16–25 years | 90 | 24.4% |

| 26–35 years | 91 | 24.7% | |

| 36–45 years | 89 | 24.1% | |

| 46–55 years | 82 | 22.2% | |

| 56 years and above | 17 | 4.6% | |

| Total | 369 | 100% | |

| Marital status | Single | 146 | 39.6% |

| Married | 220 | 59.6% | |

| Divorced | 1 | 0.3% | |

| Widow/Widower | 2 | 0.6% | |

| Total | 369 | 100% | |

| Educational qualification | |||

| Secondary School | 19 | 5.2% | |

| ND/NCE | 80 | 21.6% | |

| HND | 22 | 6% | |

| Bachelor | 135 | 36.6% | |

| Master and Doctoral degree | 108 | 29.3% | |

| Others | 5 | 1.4% | |

| Total | 369 | 100% | |

| Type of Telephone Users | ||

|---|---|---|

| Percent | Cumulative Percent | |

| Self-employed business owner | 50 | 13.6% |

| Academic Lecturer and Student | 118 | 32.0% |

| Unemployed person | 9 | 2.4% |

| Private sector employee | 102 | 27.6% |

| Public sector employee | 90 | 24.4% |

| Total | 369 | 100% |

| H5. | Frequency | Percent | Cumulative Percent |

|---|---|---|---|

| 90 | 24.4 | 24.4 |

| 20 | 5.4 | 29.8 | |

| 3 | 0.8 | 30.6 | |

| 3 | 0.8 | 31.4 | |

| 100 | 27.1 | 58.5 | |

| 66 | 17.9 | 76.4 | |

| 10 | 2.7 | 79.1 | |

| 10 | 2.7 | 81.8 | |

| 6 | 1.6 | 83.5 | |

| 21 | 5.7 | 89.2 | |

| 24 | 6.5 | 95.7 | |

| 16 | 4.3 | 100.0 | |

| 369 | 100.0 |

| Perception of CSR | Mean Rank |

|---|---|

| 4.35 |

| 3.81 |

| 2.64 |

| 3.28 |

| 3.53 |

| 3.38 |

| Perception of Entrepreneurship | Mean Rank |

|---|---|

| 2.58 |

| 2.71 |

| 2.87 |

| 3.39 |

| 3.45 |

| SN | Strongly Agree (SA), Agree (A), Neither Agree nor Disagree (N) Disagree (D) and Strongly Disagree (SD) | SA | A | N | D | SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I1. | Future CSR could be targeted at funding entrepreneurship education in the primary, secondary, and tertiary institutions. | 47.4% | 36.3% | 12.7% | 3.3% | 0.3% |

| I2. | CSR investments could be used as seed funds for start-ups/small ventures created by the unemployed graduates after their entrepreneurship training. | 44.2% | 40.9% | 10.8% | 3.0% | 1.1% |

| I3. | CSR could support building business clusters and technology business incubation centres for the benefit of small businesses in Nigeria. | 41.5% | 36.0.% | 16.8% | 4.9% | 0.8% |

| I4. | CSR investments could be used for buying the needed equipment and tools for artisans, craftsmen, and petty traders in disadvantaged host communities. | 37.9% | 34.1% | 18.4% | 7.9% | 1.6% |

| I5. | CSR programmes companies could be good instruments for political risk mitigation in hostile communities like the Niger Delta and Northern Nigeria. | 29.8% | 35.2% | 21.4% | 8.7% | 4.9% |

| Coefficients | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | Unstandardised Coefficients | Standardised Coefficients | t | Sig. | |

| B | Std. Error | Beta | |||

| (Constant) | 12.176 | 1.628 | 7.479 | 0.000 | |

| EVC | −0.009 | 0.041 | −0.016 | −0.230 | 0.818 |

| NIC | −0.018 | 0.042 | −0.034 | −0.439 | 0.661 |

| SIC | 0.028 | 0.056 | 0.035 | 0.502 | 0.616 |

| SMC | 0.230 | 0.052 | 0.286 | 4.435 | 0.000 |

| EIC | 0.191 | 0.071 | 0.144 | 2.680 | 0.008 |

| Location of respondent | 0.025 | 0.081 | 0.016 | 0.314 | 0.754 |

| Sex | −0.257 | 0.433 | −0.032 | −0.593 | 0.553 |

| Age | −0.290 | 0.237 | −0.101 | −1.227 | 0.221 |

| Marital Status | 0.621 | 0.518 | 0.094 | 1.199 | 0.231 |

| Educational Qualifications | −0.283 | 0.158 | −0.105 | −10.790 | 0.074 |

| Model | R | R Square | Adjusted R Square | Std. Error of the Estimate | Change Statistics | Change Statistics | Durbin–Watson | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R Square Change | F Change | df1 | df2 | Sig. F Change | ||||||

| 1 | 0.395 a | 0.156 | 0.132 | 3.220 | 0.156 | 6.620 | 10 | 358 a | 0.000 | 1.795 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Raimi, L.; Panait, M.; Grigorescu, A.; Vasile, V. Corporate Social Responsibility in the Telecommunication Industry—Driver of Entrepreneurship. Resources 2022, 11, 79. https://doi.org/10.3390/resources11090079

Raimi L, Panait M, Grigorescu A, Vasile V. Corporate Social Responsibility in the Telecommunication Industry—Driver of Entrepreneurship. Resources. 2022; 11(9):79. https://doi.org/10.3390/resources11090079

Chicago/Turabian StyleRaimi, Lukman, Mirela Panait, Adriana Grigorescu, and Valentina Vasile. 2022. "Corporate Social Responsibility in the Telecommunication Industry—Driver of Entrepreneurship" Resources 11, no. 9: 79. https://doi.org/10.3390/resources11090079

APA StyleRaimi, L., Panait, M., Grigorescu, A., & Vasile, V. (2022). Corporate Social Responsibility in the Telecommunication Industry—Driver of Entrepreneurship. Resources, 11(9), 79. https://doi.org/10.3390/resources11090079