Abstract

This research article investigates the recycling of end-of-life solar photovoltaic (PV) panels by analyzing various mechanical methods, including Crushing, High Voltage Pulse Crushing, Electrostatic Separation, Hot Knife Cutting, Water Jet Cutting, and Magnetic Separation. Each method’s effectiveness in extracting materials such as glass, silicon, metals (copper, aluminum, silver, tin, lead), and EVA was evaluated. The analysis reveals that no single method is entirely sufficient for comprehensive material recovery. Based on the data analysis, a new hypothetical hybrid method, Laser and High Voltage Pulse (L&HVP), is proposed, which integrates the precision of laser irradiation with the robustness of high voltage pulse crushing. The laser irradiation step would theoretically facilitate the removal of the ethylene-vinyl acetate (EVA) encapsulant, preparing the materials for subsequent separation. The high high-voltage pulse crushing would then selectively fragment and separate the remaining components, potentially enhancing material recovery efficiency while minimizing contamination. The proposed approach is grounded in the observed limitations of existing techniques. This method aims to offer a more comprehensive and sustainable solution for solar PV module recycling. Further research and experimentation are necessary to validate the effectiveness of the L&HVP method and its potential impact on the field of solar PV recycling.

1. Introduction

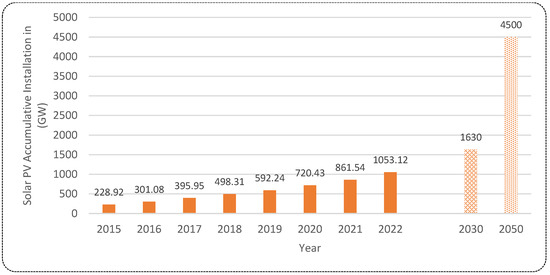

Solar power offers an endless and sustainable energy supply, positioning it as a superior choice compared to limited and polluting resources like coal, oil, and other conventional sources. It provides a dependable, economical, and eco-friendly method for electricity generation [1,2]. At present, solar photovoltaic (PV) technology is rapidly emerging as the leading energy source globally due to its sustainability and minimal environmental impact. Since 2015, solar PV has consistently shown a rise in investment, marking it as the only uninterruptedly growing electricity-generating technology. Projections indicate that the worldwide installed capacity of solar PV will keep increasing, potentially reaching 1630 GW by 2030 and as much as 4500 GW by 2050, as illustrated in Figure 1 [3,4,5].

Figure 1.

Solar PV accumulative instillation projection till 2030 and 2050 [1].

In the 2016 publication by IRENA and IEA-PVPS, the agencies offered pioneering global forecasts for photovoltaic (PV) panel waste volumes through 2050. Their analysis included a standard loss scenario reflecting an average PV panel lifespan of 28 years and an early loss scenario incorporating various failure phases, leading to a reduced average lifespan of 26 years [6,7].

- Standard Loss Scenario: This scenario predicts that PV panels will gradually degrade in efficiency over a typical lifespan of 25 to 30 years. As the panels age, their energy output declines progressively, eventually falling below the threshold for viable operational use. End-of-life options in this scenario include the decommissioning and disposal of the panels, with an emphasis on recycling to reclaim valuable components such as silicon and silver while preventing environmental contamination.

In this scenario, most panels are retired due to the natural decrease in performance over time. Recycling and waste management systems play crucial roles in handling these retired panels, focusing on the recovery of essential materials and mitigating environmental risks.

- Early Loss Scenario: This scenario addresses premature failures and significant efficiency reductions before panels reach their expected lifespan, classified into ‘infant,’ ‘mid-life,’ and ‘wear-out’ stages.

- ▪

- Infant failures occur typically within the first four years, with the most common within two years of installation.

- ▪

- Mid-life failures are generally observed between the fifth and eleventh years.

- ▪

- Wear-out failures appear from the twelfth year onwards, leading up to the projected end-of-life at 30 years.

Such early failures can lead to increased waste production and pose additional challenges in waste management.

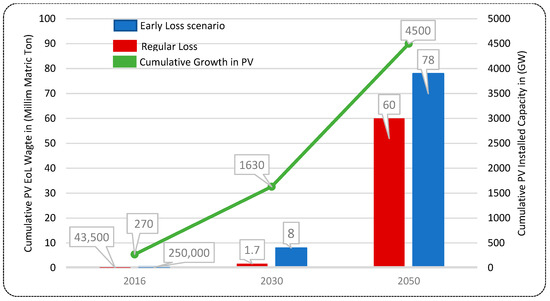

Both scenarios anticipate a decline in panel efficiency over time, projecting a minimum operational lifespan of 25–30 years. IRENA estimates that, under the early loss scenario, the total volume of end-of-life PV panels could amount to between 8 and 78 million metric tons from 2030 to 2050, as depicted in Figure 2 [6].

Figure 2.

Projected generation of end-of-life waste from solar PV panels between 2030 and 2050 [5,6].

Predicting which countries will generate the most solar photovoltaic (PV) waste at end-of-life (EOL) is complex. This prediction depends largely on the adoption rate of solar PV systems, their durability, and the presence of recycling infrastructure. As highlighted in the previously referenced Figure 2, there is a pressing need to develop effective recycling strategies for solar PV waste to reduce environmental impacts.

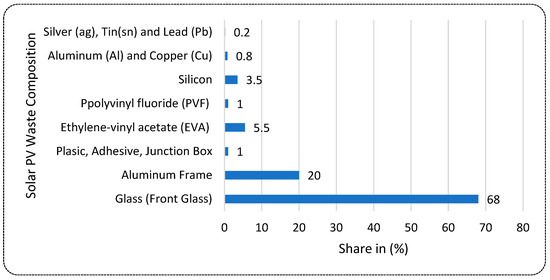

Solar PV waste comprises a variety of materials, including glass, metals, plastics, and semiconductors. Studies detailed in sources such as [8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15] indicate that a typical silicon-based solar panel consists of approximately 68% glass (used for the front cover), 20% aluminum (used for the frame), and 1% copper (found in junction boxes and cables). Additionally, it contains 5.5% ethylene-vinyl acetate (EVA) encapsulant, 1% polyvinyl fluoride (PVF) back sheet, and about 3.5% silicon, with small quantities of aluminum and copper. The solar cell itself contains around 0.2% of precious and hazardous metals, including silver, tin, and lead. It is important to note that these percentages can vary based on the specific type of solar module and the manufacturing processes used, as depicted in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Solar PV Module Waste Composition in (%).

Currently, two main recycling methods are prevalent: mechanical (physical) and chemical. This study will concentrate on a detailed evaluation of the recycling techniques for solar PV EOL waste, with a particular focus on the mechanical recycling method because of its potential as a sustainable and scalable approach to material recovery. Mechanical recycling methods, such as crushing, high-voltage pulse crushing, and electrostatic separation, offer several advantages over chemical techniques. They avoid the use of hazardous reagents, minimizing environmental and health risks, and are generally more cost-effective due to lower operational and material handling costs. Furthermore, mechanical methods consume less energy and produce fewer byproducts, aligning with the principles of a circular economy.

Chemical recycling, while capable of achieving high material purity, often involves complex waste management and higher capital investments, making it less feasible for large-scale applications. In contrast, mechanical recycling is well-suited to regions with limited access to advanced chemical processing facilities and offers a pragmatic solution for initial material separation and recovery.

Despite considerable advancements in the field of solar PV recycling, existing mechanical methodologies face persistent challenges that limit their efficiency and scalability. Current mechanical techniques often struggle with precise material separation, leading to contamination and reduced recovery yields. Thermal methods, while effective in some cases, require high energy inputs, which increase operational costs and environmental impacts. Furthermore, these conventional approaches frequently fail to maintain the structural integrity of valuable components, such as silicon wafers and metallic elements, further reducing the economic viability of the recycling process.

In this paper, we propose the Laser and High Voltage Pulse (L&HVP) method as a hypothetical solution to address the challenges of solar PV module recycling. This conceptual approach combines the theoretical precision of laser irradiation with the anticipated efficiency and robustness of high-voltage pulse crushing. Laser irradiation is hypothesized to selectively remove the ethylene-vinyl acetate (EVA) encapsulant, potentially preserving the structural integrity of critical components such as silicon wafers and metallic elements. Following this, high-voltage pulse crushing is envisioned to facilitate efficient material fragmentation and separation, enabling the recovery of high-purity glass, silicon, and metals with minimal contamination. While this method has yet to be experimentally validated, it aims to address the limitations of current mechanical and thermal techniques by offering a potentially scalable, sustainable, and efficient solution. Future research and experimental studies will be carried out to confirm its feasibility, optimize its design, and evaluate its practical applications in solar PV recycling.

2. Literature Survey

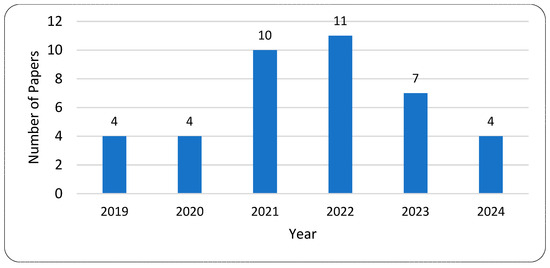

From 2019 to 2024, a total of 40 research articles discussing solar PV end-of-life (EoL) waste recycling have been published in various ISI journals, as shown in Figure 4. These publications cover a wide array of topics, including the challenges and strategies for managing photovoltaic (PV) waste, technological advancements in recycling processes, policy recommendations, and comprehensive reviews of global trends and future perspectives. The primary focus has been on improving recycling efficiency, recovering valuable materials, and integrating sustainable practices within the circular economic framework. A detailed list of these published articles is provided in Table 1. However, it is noteworthy that none of these papers specifically focus on mechanical methods for PV waste recycling, highlighting a significant gap in the existing literature. This gap underscores the importance of our work, which aims to address this overlooked aspect and contribute to the advancement of PV waste recycling techniques.

Figure 4.

Numbers of Papers Published on Solar PV EoL waste Recycling from (2019–2024).

Table 1.

List of Papers published on Solar PV EoL waste Recycling.

3. Research Methodology

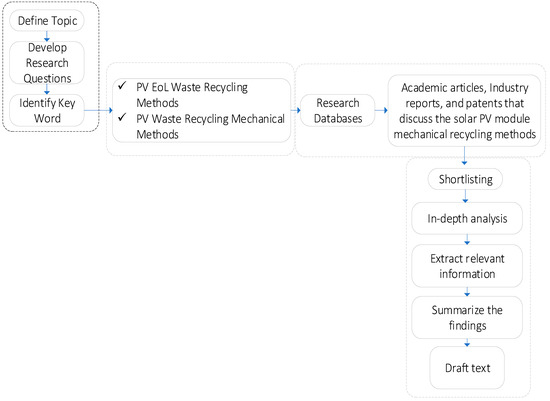

The research methodology for this study follows a structured approach, as illustrated in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Methodology for Mechanical Recycling Method.

- Define the Research Topic: focuses on assessing the mechanical recycling methods for solar photovoltaic (PV) end-of-life (EoL) waste. This involves understanding the various mechanical techniques employed in recycling PV modules that have reached the end of their operational life.

- Develop Research Questions to address the following key research questions:

- ▪

- What are the current mechanical recycling methods available for PV EoL waste?

- ▪

- How effective are these mechanical methods in recycling PV modules?

- ▪

- What are the benefits and limitations of each method?

- Identify Key Words include:

- ▪

- PV EoL Waste Recycling Methods

- ▪

- PV Waste Recycling Mechanical Methods

- Literature Review: begins with an extensive literature review to gather existing knowledge and data on the topic. This involves searching for:

- ▪

- Academic Articles: Peer-reviewed papers that discuss mechanical recycling methods for PV modules.

- ▪

- Industry Reports: Documents from industry stakeholders that provide insights into practical applications and the effectiveness of recycling methods.

- ▪

- Patents: Information on patented technologies and innovations in mechanical recycling of PV waste.

- Data Collection from Research Databases: The identified keywords are used to search various research databases, including but not limited to:

- ▪

- Google Scholar

- ▪

- ScienceDirect

- ▪

- IEEE Xplore

- ▪

- Scopus

This ensures a comprehensive collection of relevant academic articles, industry reports, and patents.

- 6.

- Shortlisting Relevant Sources

- ▪

- The collected literature is then shortlisted based on relevance to the research questions. Criteria for shortlisting include:

- ▪

- Direct discussion on mechanical recycling methods for PV modules.

- ▪

- Recent publications to ensure up-to-date information.

- ▪

- Sources that provide empirical data and detailed descriptions of recycling processes.

- 7.

- In-depth Analysis involves:

- ▪

- Evaluating the effectiveness of different mechanical recycling methods.

- ▪

- Analyzing the processes, technologies, and outcomes reported in the literature.

- ▪

- Comparing the benefits and limitations of each method.

- 8.

- Extraction of Relevant Information focusing on:

- ▪

- Descriptions of mechanical recycling techniques.

- ▪

- Performance metrics and results from practical implementations.

- ▪

- Comparative analysis of different methods.

- 9.

- Summarizing the Findings

- ▪

- The extracted information is summarized to provide a clear and concise overview of the current state of mechanical recycling methods for PV EoL waste. This summary highlights:

- ▪

- The most commonly used methods.

- ▪

- Innovations and advancements in the field.

- ▪

- Gaps and challenges that need further research.

- 10.

- Drafting the Research Article

- ▪

- Based on the summarized findings, the research article is drafted.

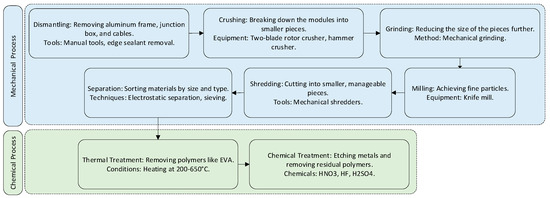

4. Mechanical Recycling Process

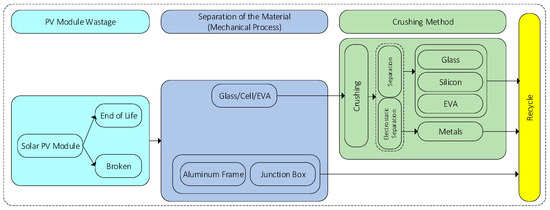

The mechanical recycling process for photovoltaic (PV) modules is a meticulously planned and executed series of steps designed to dismantle the modules and recover valuable materials efficiently and sustainably [54,55]. This detailed sequence not only ensures the effective and efficient recycling of PV modules but also supports environmental sustainability by minimizing waste and promoting the reuse of materials. A comprehensive flowchart of this process is depicted in Figure 6 for a visual representation of each step.

Figure 6.

Solar PV Mechanical Separation Method Flowchart.

The process explanation is given in the following detailed steps:

- Disassembly: The initial stage involves the careful dismantling of the PV module. This step is crucial as it prepares the module for further processing by removing frames, junction boxes, and other easily separable components. This facilitates the subsequent breakdown of the module into more manageable pieces.

- Breaking Down: Once the outer components are removed, the module is broken into smaller sections. This is typically achieved through manual or mechanical cutting tools, depending on the volume and nature of the modules being processed.

- Size Reduction: The smaller sections are then subjected to size reduction, where they are further fragmented into finer particles. This is often accomplished through crushing or milling processes. The aim here is to reduce the material to sizes that are suitable for subsequent separation techniques.

- Sieving: Following size reduction, sieving is employed to classify the crushed materials into different size fractions. This step is essential for efficiently sorting materials and facilitates the separation of glass, metals, and other components based on size.

- Dense Media Separation: After sieving, dense media separation is used to segregate materials based on their density. This technique involves using a medium, typically a liquid or heavy suspension, that is calibrated to a specific density. Materials that are denser than the medium sink, while less dense materials float. This method is particularly effective for separating valuable metals from less dense materials like plastic and glass.

- Material Recovery: The separated materials are then collected and prepared for recovery. This includes the extraction of metals like silver and copper, which are valuable for reuse in manufacturing new products. The recovery process is critical for maximizing the value derived from recycled materials and reducing the need for virgin resources.

- Integration into Production Cycle: Finally, the reclaimed materials are cleaned, processed, and reintegrated into the manufacturing cycle. This step closes the loop in the recycling process, contributing to the circular economy by reducing waste and the consumption of raw materials.

4.1. Crushing

In the mechanical recycling process, simple crushing plays a critical role in size reduction [56]. Sometimes, the crushing process is categorized into mechanical crushing [57] and high-pressure pulse crushing [58]. Broadly, crushing is considered a basic or initial process of the mechanical recycling process of waste solar PV panels. In [59], a new mechanical treatment process called “Conventional Crushing” is discussed. Figure 7 shows the step-by-step process of the experimental investigation.

Figure 7.

Mechanical processing proposed by [26].

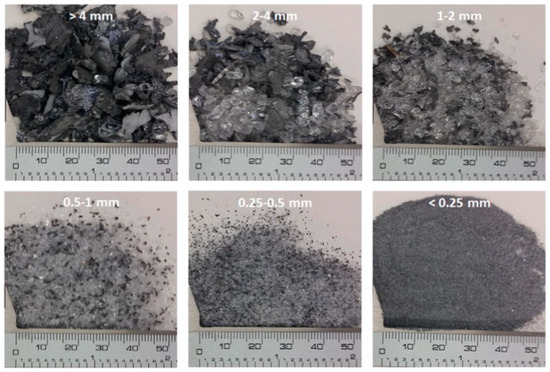

In the conventional crushing (industrial processing) of crystalline silicon (c-Si) based photovoltaic (PV) panels, after removing the aluminum frame and junction box, the panels were cut into smaller sections (approximately 20 cm × 30 cm) and subjected to an industrial crushing process using a rapid granulator with a multi-blade, triple knife rotor.

The crushing of c-Si PV panels using this method proved to be challenging due to the strong bonding between the ethylene vinyl acetate (EVA) encapsulant and the glass and PV cells. The process resulted in a heterogeneous material with various particle size fractions, requiring multiple crushing runs to achieve the desired particle size. The distribution of materials across different size fractions is visually represented in Figure 8, which shows the images of sieved fractions of the crushed photovoltaic panel at different particle size ranges (>4 mm, 2–4 mm, 1–2 mm, 1–0.5 mm, 0.25–0.5 mm, and <0.25 mm).

Figure 8.

Visual breakdown of photovoltaic panel fragments post-crushing, categorized by particle size ranges (>4 mm, 2–4 mm, 1–2 mm, 1–0.5 mm, 0.25–0.5 mm, and <0.25 mm) [58].

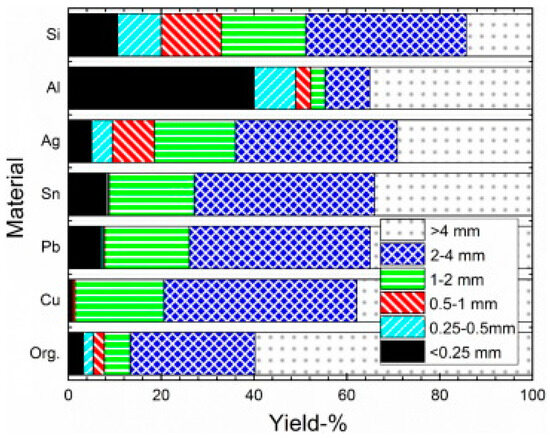

Figure 9 provides a detailed breakdown of the distribution of aluminum (Al), silver (Ag), tin (Sn), lead (Pb), copper (Cu), and organic matter (wt%) among the different size fractions. The results indicated that nearly 90% of the organic matter from the industrially crushed PV panels was found in fractions larger than 2 mm. Conversely, copper was predominantly present in fractions larger than 1 mm, with significant amounts in the 2–4 mm and >4 mm fractions. The metals Pb and Sn showed a similar distribution pattern, with most of these metals located in the >2 mm size range. Additionally, the results highlighted a lack of selectivity in material distribution among the screened fractions, which could complicate subsequent recovery steps in a recycling process.

Figure 9.

Weight percentage distribution of Al, Ag, Sn, Pb, Cu, and organic matter across sieved size fractions (>4 mm, 2–4 mm, 1–2 mm, 1–0.5 mm, 0.25–0.5 mm, and <0.25 mm) from industrially crushed PV panels [58].

The conventional crushing method, as employed in this study, demonstrated significant limitations in its ability to selectively separate the various materials embedded within the crystalline silicon (c-Si) based photovoltaic (PV) panels. This process involves mechanically breaking down the panels into smaller particles using an industrial granulator, which is effective in reducing the overall size of the material but does not effectively differentiate between the different components, such as metals, glass, and polymers.

One of the primary challenges observed with this method is its inability to achieve a clear separation of valuable metals from the rest of the panel materials. The strong bonding between the ethylene vinyl acetate (EVA) encapsulant and the glass and PV cells results in a heterogeneous mix of materials after crushing, where metals like copper (Cu), silver (Ag), tin (Sn), and lead (Pb) are dispersed across a wide range of particle sizes. As a result, the recovery of valuable metals becomes more complex and less efficient.

4.2. High Voltage Pulse Crushing (HVPC)

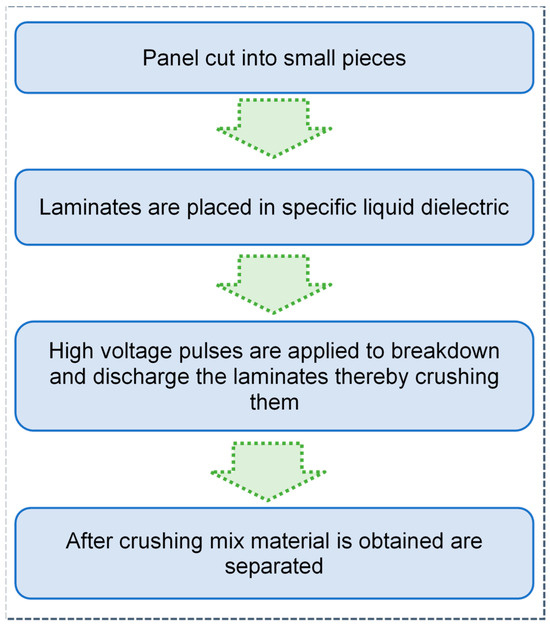

The use of HVPC technology is prevalent in the recycling of electronic waste circuit boards. Similarly, there are similarities between PV and electronic waste, prompting researchers to investigate the use of HVPC in the recycling of PV modules. It intends to improve the effectiveness and sustainability of recycling methods for abandoned PV modules, hence advancing environmentally friendly solutions in the field of electronic waste management. HVPC technology is capable of successfully separating different layers of material in the waste solar PV modules, and it has the potential to lead to environmentally acceptable recycling operations. The HVPC process flowchart is presented in Figure 10.

Figure 10.

Process flowchart of HVPC.

The application of HVPC involves crushing and separating solar cell materials using high-voltage (HV) pulses [60]. HVPC is the most appropriate technology to replace conventional crushing. With HV application to the recycling material, stress is generated, which causes its fragmentation [61]. This process is useful to separate elements such as silicon from glass or other components within the solar cell [62]. The use of HVPC for crushing the waste PV modules is an efficient and cost-effective approach, particularly for large-scale recycling projects. Several research studies have examined the HVPC process with different parameters.

Akimoto et al. [63] study utilized high-voltage pulse crushing technology combined with sieving and dense medium separation to selectively separate and recover materials from polycrystalline silicon photovoltaic panels. Their methodology for crushing involves two steps of crushing, i.e., primary crushing and secondary crushing

4.2.1. Primary Crushing Step

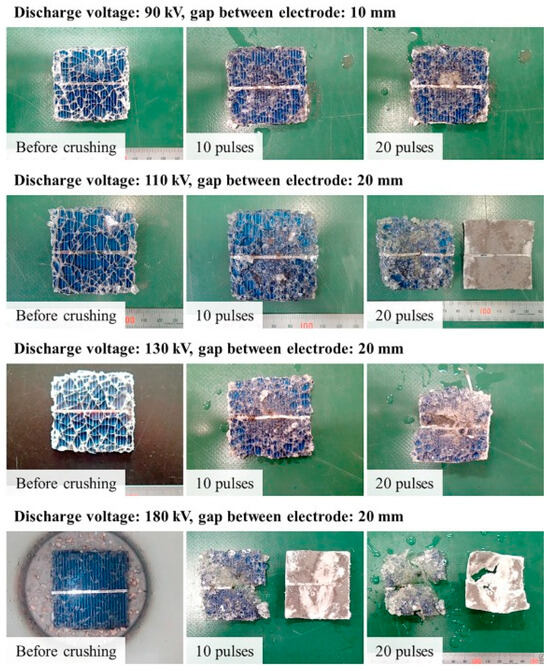

In this step, the objective was to separate the photovoltaic panel into two distinct layers: the glass layer and the back sheet layer. The experiments were performed under various conditions to determine the optimal parameters for effective separation without significant material destruction. The experiments were conducted at discharge voltages of 90 kV, 110 kV, 130 kV, and 180 kV with a gap of 10–20 mm between the electrodes and a discharge frequency of 5 Hz, as given in Figure 11.

Figure 11.

Results from the primary crushing step under different processing conditions [63].

Figure 11 presents the outcomes of the primary crushing step, showing the separation of the photovoltaic panel into the glass layer (left) and the back sheet layer (right) under two sets of conditions: 110 kV for 20 pulses and 180 kV for 10 pulses. The results indicated that the condition of 110 kV with 20 pulses was optimal for achieving mutual separation of the layers while retaining their form. This condition was preferred over the 180 kV condition because it allowed for better handling of the crushed products and reduced contamination risks. The primary crushing process involved two main mechanisms: electrical disintegration (ED) and electrohydraulic disintegration (EHD), where the optimal condition likely balanced these mechanisms for effective material separation.

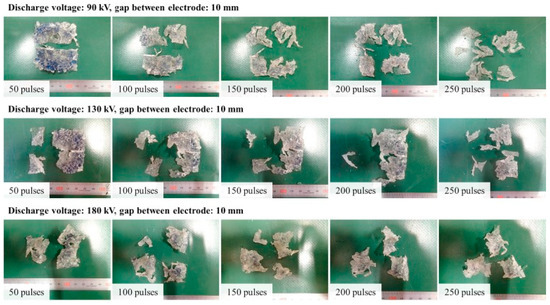

4.2.2. Secondary Crushing Step

Following the primary separation, each layer (glass and back sheet) underwent a secondary crushing step under varying conditions to further liberate materials. This step was designed to enhance the separation of encapsulated components, particularly to isolate the glass particles from the encapsulant and to separate the bus-bar electrode from the back sheet.

Figure 12 illustrates the products obtained after the secondary crushing step of the glass layer. The results show that glass particles were effectively removed under all tested conditions, with the encapsulant being destroyed at higher discharge voltages. The optimal condition for the secondary crushing step was identified as 90 kV for 250 pulses. Under this condition, the bus-bar electrode was effectively separated from the encapsulant, and mutual separation of materials was achieved without significant destruction of each component. The study highlights that maintaining the structural integrity of the materials during separation is crucial for enhancing the purity of the recovered glass and facilitating further material recovery processes.

Figure 12.

Results from the secondary crushing step of the glass layer following the removal of glass particles [63].

High-voltage pulse crushing has proven to be a highly effective technique for the selective separation and recovery of valuable materials from end-of-life photovoltaic (PV) waste panels. This method leverages the unique ability to target specific material interfaces, enabling the liberation of valuable components, such as metals and silicon, with greater precision compared to traditional crushing techniques. By generating high-intensity electrical pulses, the method induces micro-explosions and shock waves that facilitate the disintegration of bonded materials, leading to cleaner separation.

4.3. Electrostatic Separation (ESS)

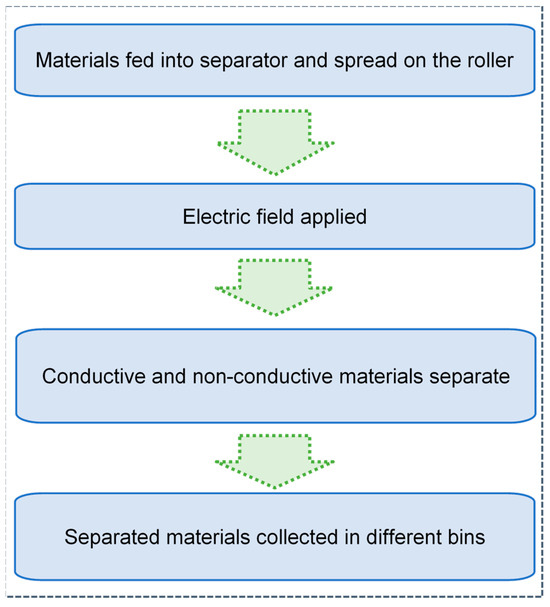

Electrostatic separation (ESS) is a useful method for sorting charged or polarized particles using an electric field. It is extensively employed in the recycling of PCBs and PV waste. This procedure uses a roll-type corona electrostatic separator with grounded and active electrodes to separate conductive and nonconductive particles based on their electrical conductivities [64,65,66]. The generalized process flowchart is shown in Figure 13.

Figure 13.

Process flow of Electrostatic separation.

ESS has proved its efficiency in concentrating metals like silver, aluminum, and silicon from solar panel fragments, obtaining high recovery rates of up to 95% for specific minerals [9,56,67]. By altering parameters such as electric potential difference, rotation speed, and electrode spacing, ESS is demonstrated to be a low-cost, energy-efficient technology for extracting important metals with high purity levels. After mechanical crushing, the majority of the silicon is converted to powder, which can be recovered by electrostatic separation.

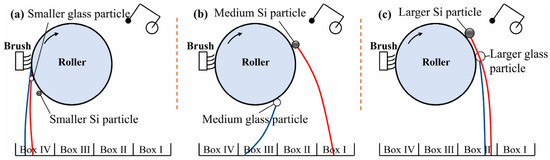

ESS involves segregating conductive and non-conductive objects. A vibrating feeder is used to deliver a mixture of metals intended for separation onto a grounded, moving metal roller, as shown in Figure 14. The combination is then transported to a corona electrode region and charged by exposing it to a high voltage of up to 35 kVs. Conductive components, such as metals, quickly discharge their electrical charge to the roller as it rotates, causing them to be evacuated. Non-conductive materials, on the other hand, keep their charge for a longer period of time and adhere to the roller’s surface until cleaned using a brush. Corona roll separators are an important technology in the electrostatic separation process because they effectively separate conductive and non-conductive components of the material combination.

Figure 14.

Electrostatic Separation process for various particle sizes [56].

Dias et al. also used the ESS technique to extract the valuable material from the PV waste modules. They fixed the splitter angles and feeder speed while changing the voltage and roller speed to determine the optimal parameters for the ESS process. They also evaluated the efficiency of the separation using ICP-OES for the metals, XRD for glass and silicon, and mass difference for the EVA. Their study suggested that the voltage of 24–28 kV and rotation speed of the roller of 30 is ideal for the highest yield [65].

De Souza and Veit recycled the PV panels using ESS. They initially separated the aluminum frame from the PV panels and ground the rest of the material using knife mills to reduce the size of the material. The material is then divided into three sets based on the size of the particle. An electrostatic separator with a roller type is used to further separate the conductive and non-conductive material. Various experiment settings are examined to effectively separate the various metal concentrations presented in the mixture. An electric potential difference of 38 kV is found to be the optimal voltage with a rotation speed of 75 rotations per minute (rpm). The ionization electrode is placed 25 cm from the roller at an angle of 55 degrees to obtain the highest metallic concentrations from the grounded PV mixture. These experimental settings for the ESS are able to achieve the highest metallic concentrations [67].

Li et al. used ESS to recover Si from crushed PV panels. The panel was mechanically broken into chunks and blended powder. The blended powder includes 82.8% silicon. The ESS technique is used to determine the impacts of particle size, voltage, and roller rotation speed. The particle size range of 0.30–0.45 mm was determined to be ideal for the separation process. The voltage given to the electrostatic electrode ranged from 15 to 22 kV, and the roller’s rotation speed was regulated between 20 and 60 rpm. The best results were obtained with a voltage of 15 kV and a rotation speed of 30 rpm, resulting in a Si proportion of 91.0% and a Si recovery rate of 48.9%. Li et al. concluded that combining mechanical crushing with ESS is a potential technology for recovering Si from waste PV panels, providing both economic and environmental benefits [56].

4.4. Hot Knife Knife-Based Delamination Process

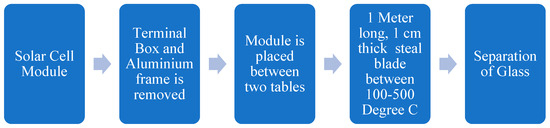

A hot Knife is one of the mechanical cutting techniques used for the separation of glass of Solar PV from panel cells [68,69,70,71,72]. This technique was invented by Japan’s c-Solar PV Recycling company. It performs only one function of the recycling process [73,74,75,76]. The flow diagram of the Hot Knife technique is shown in Figure 15.

Figure 15.

Process Flow Diagram for Hot Knife.

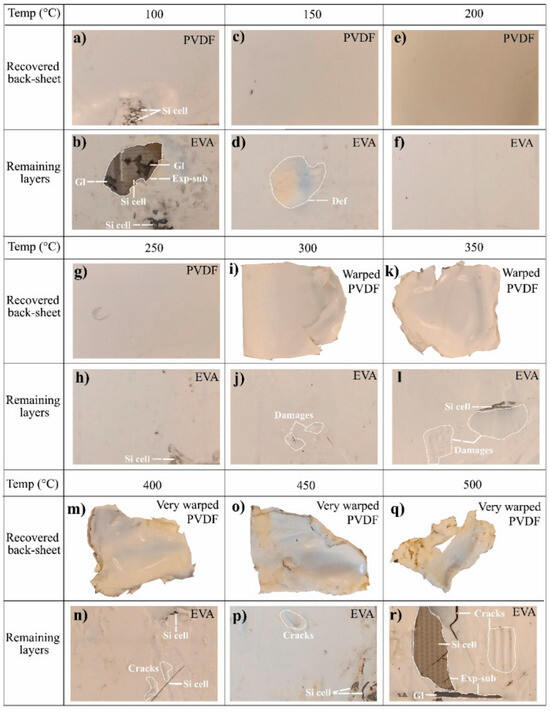

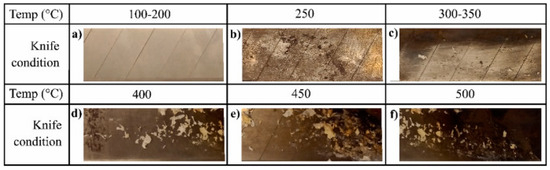

In [77], the study explores the application of the hot knife technique for the efficient separation and recovery of the back sheet from crystalline silicon (c-Si) photovoltaic (PV) modules. This method employs a thin, highly conductive knife heated by a hot air gun to temperatures ranging from 100 °C to 500 °C. The objective is to soften the adhesives by bonding the back sheet to the PV module, facilitating clean separation without damaging other layers, especially the sensitive photovoltaic cells.

Nine samples from a monocrystalline silicon PV panel were subjected to varying temperatures to determine the optimal conditions for back sheet separation. As given in Figure 16a–r, the temperatures tested were 100 °C, 150 °C, 200 °C, 250 °C, 300 °C, 350 °C, 400 °C, 450 °C, and 500 °C. The effectiveness of the hot knife process was evaluated based on the recovery rate, purity of the back sheet material, and the condition of the remaining PV module layers.

Figure 16.

Condition of the back sheet (PVDF) and remaining layers (EVA) in the panel sample after exposure to varying hot knife temperatures, ranging from 100 °C to 500 °C [77].

Figure 16 demonstrates the impact of varying temperatures on the separation process. At 100 °C and 150 °C, the hot knife was insufficiently effective, requiring manual peeling to complete the separation. This resulted in significant damage to the back sheet and other layers, with recovery rates of 4.28% and 4.44%, respectively, and purities of 95.65% and 99.19%. As the temperature increased to 200 °C, the separation process became more efficient, with the knife sliding smoothly between layers, achieving a recovery rate of 4.45% and the highest purity of 99.42%. Higher temperatures (250 °C to 500 °C) led to faster separation but also caused thermal deformation of the back sheet, with a significant decrease in purity to as low as 68.36% at 500 °C.

The hot knife technique at 200 °C provided the best balance between efficiency and material integrity, as evidenced by the high purity and minimal damage to the remaining layers.

Figure 17a–f details the condition of the knife after each temperature stage from (100–500 °C), correlating the physical state of the knife with the separation quality. The knife remained clean at lower temperatures, while higher temperatures led to material buildup on the knife, indicating excessive melting and adhesion of the back sheet material, which correlates with the decreased purity at those temperatures.

Figure 17.

Condition of the knife after exposure to each temperature level during the hot knife technique experiments [77].

The study successfully demonstrates the hot knife technique’s effectiveness in recovering high-purity back sheets from c-Si PV modules, particularly at an optimal temperature of 200 °C. This method offers significant advantages over traditional thermal treatments by reducing environmental impact and preserving the material quality, making it a promising solution for sustainable PV panel recycling.

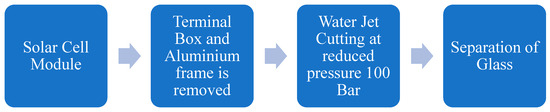

4.5. Water Jett Cutting of Solar PV

The water jet process utilizes a high-pressure stream of water, frequently combined with an abrasive substance, to cut a diverse range of materials. Widely acknowledged as one of the most versatile and rapidly advancing processes across industries, it has been demonstrated to offer greater benefits and cost-effectiveness compared to traditional methods such as laser cutting, EDM wire cutting, machining, oxy-fuel cutting, plasma cutting, and diamond tool cutting. Water jets have virtually limitless capabilities when it comes to cutting and machining various materials [78].

Shintora Kosan, a Japanese company, has pioneered an innovative water jet technology specifically designed for reclaiming glass from end-of-life PV modules. Water jet cutting makes recycling glass from these units affordable, efficient, and beneficial. After damaging the glass, whatever the success rate of any method, more energy is required to recycle the glass than can be saved by removing the glass. This technology can separate the solar cells and the back sheets by spraying water without damaging the glass. Following this process, the glass exhibits no signs of harmful substances or damage. Additionally, the machine incorporates a special filtration device to remove wastewater [79,80]

It was discovered during the early 1970s that water pressure ranging between (40,000 PSI to 60,000 PSI) and 276 MPa and 414 MPa could precisely cut soft materials using a 0.1 mm water jet stream. By the early 1980s, a specialized nozzle was developed alongside standard water jet components, allowing for the introduction of a minor quantity of abrasive power into the waterjet. This innovation, known as “abrasive jets,” propelled materials like garnet from the nozzle at high speeds, enabling the cutting of hard and tough materials like stainless steel, titanium, glass, and ceramics with excellent results. Consequently, this technology is now effectively converting waste into valuable commodities [81].

Presently, companies are offering waterjet cutting services mainly for thin film panels and the separation of glass plates from EoL Si PV panels. Two Two-axis industrial robotic waterjet systems for metal cutting are available commercially. The energy consumption for glass separation is about 20 kilowatts, and one operator is required for this purpose. The separated glass is neat and clean and needs no further processing for EVA removal. CNC CNC-based water jet jet-cutting machines having robotic arms can also be used for water jet jet-cutting purposes. The process flow diagram can be elaborated as in Figure 18.

Figure 18.

Process Flow Diagram for Water Jet Cutting.

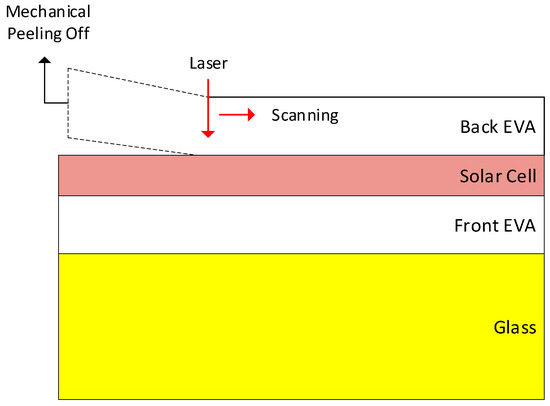

4.6. Laser Irradiation

The study in [46] investigated laser irradiation as a method for recycling the ethylene-vinyl acetate (EVA) layer from crystalline silicon (c-Si) photovoltaic (PV) modules, which presents a significant advancement in sustainable recycling technologies. The research focuses on optimizing the laser parameters to effectively debond the EVA layer from the solar cells without causing damage to the cells themselves. The laser irradiation process is outlined in Figure 19. This figure illustrates the sequence of steps, starting with the removal of the back sheet, followed by laser irradiation to weaken the EVA bond, and concluding with the mechanical peeling of the EVA layer.

Figure 19.

Process Flow of EVA Layer Recycling Using Laser Irradiation and Mechanical Peeling in c-Si PV Modules [46].

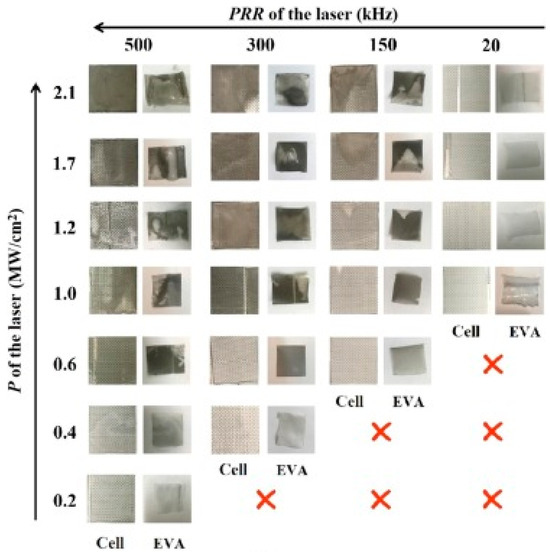

Figure 20 provides a detailed analysis of how the power density (P) and pulse repetition rate (PRR) of the laser impact the debonding process. As shown in Figure 20, higher P and PRR values enhance the debonding efficiency by increasing the energy delivered to the EVA layer, facilitating its separation from the solar cell. However, this also leads to a trade-off, as excessive energy can cause thermal damage to the underlying materials, including the solar cell’s aluminum electrodes. Figure 20 underscores the delicate balance required to optimize these parameters—sufficient energy must be applied to weaken the adhesive bonds without crossing the threshold where material degradation occurs.

Figure 20.

Effects of Laser Power Density and Pulse Repetition Rate on EVA Layer Separation Efficiency [46].

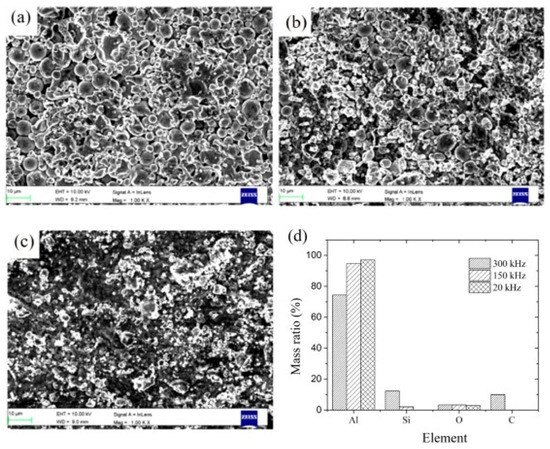

Furthermore, Figure 21a–d expands on this by illustrating the effects of different PRR settings on the physical condition of the solar cells post-EVA removal. SEM images reveal that at lower PRR settings, such as 20 kHz, the aluminum electrodes on the solar cells remain largely intact, preserving the functionality and structural integrity of the cells. However, as PRR increases, significant damage is observed, with the aluminum electrodes showing signs of deterioration and exposing the underlying silicon. This exposure can compromise the performance of the solar cells, highlighting the importance of maintaining a low PRR to protect the cells during the recycling process.

Figure 21.

SEM Analysis of Solar Cell Surface Post-EVA Removal Using Different Laser Settings [46].

5. Discussion

This study comprehensively examines various mechanical recycling technologies for photovoltaic (PV) modules, focusing on their material recovery and their advantages and disadvantages, as given in Table 2. The methods analyzed include Crushing, High Voltage Pulse, Electrostatic Separation, Hot Knife Cutting, Water Jet Cutting, and Laser Irradiation. Furthermore, in Table 3, for all the techniques, material extraction is given.

Table 2.

Recycling Methods with Their Advantages and Disadvantages.

Table 3.

Material Extraction Table of Investigated Methods.

- Crushing: This method is notable for its low energy consumption and its ability to selectively fragment PV modules, which facilitates the recovery of valuable metals. Despite these advantages, it has a relatively low silicon recovery rate and presents challenges in controlling the particle size, necessitating further research to enhance its efficiency.

- High Voltage Pulse Crushing: This technique offers efficient processing and is especially suitable for large-scale operations. It improves the possibility of recovering materials like glass, silicon powder, silver, copper, lead, and zinc. However, it suffers from incomplete separation of materials and produces potentially harmful dust, posing health risks during operations.

- Electrostatic Separation: Effective for handling dry materials, this method is characterized by its high recovery rate and purity, adding significant value. The main limitation is its effectiveness only with materials that exhibit significantly different electrical properties, which restricts its applicability.

- Hot Knife Cutting and Water Jet Cutting: Both techniques ensure fast processing with intact peeled glass and no CO2 emissions. Water Jet Cutting has the added advantage of removing rare glass without leaving ethylene-vinyl acetate (EVA) residues. Nonetheless, both require further processing to extract valuable elements from the modules.

- Water Jet Cutting: Provides a clean and precise method for separating materials in solar PV waste recycling. It effectively cuts through glass, silicon, and metals without generating heat, which helps to avoid thermal damage. However, it may struggle with EVA removal and requires a substantial amount of water and abrasive materials.

- Laser Irradiation: Offers high precision and control, proving efficient in selective material separation. However, it is a slow process, involves expensive equipment, and requires complex operation and maintenance.

Overall, the choice of recycling method depends significantly on the specific needs for material recovery, the scale of operations, and environmental considerations. Future research should aim at enhancing these technologies to increase recovery rates, reduce environmental impacts, and address the challenges noted in operational risks like dust generation and health safety in high high-voltage applications. This will help in aligning with global sustainability goals and the growing demand for raw materials in the photovoltaic industry.

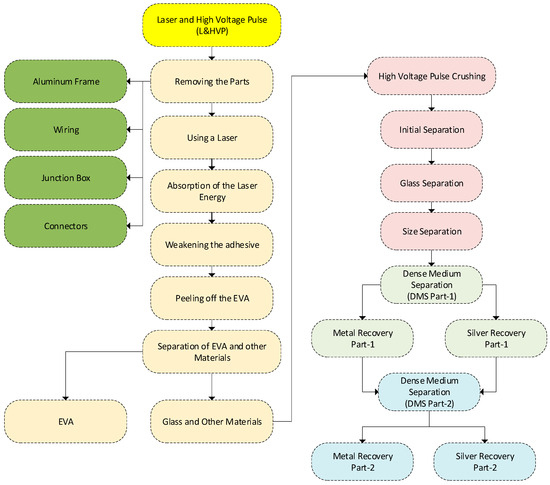

6. New Proposed Method

Building on the analysis provided in Table 1 and Table 2, this study proposes a novel and hypothetical technique that synergizes the capabilities of Laser Irradiation and High Voltage Pulse Crushing, referred to as the “Laser and High Voltage Pulse (L&HVP)” method. This hybrid approach is conceptually designed to address the limitations of existing recycling methods for end-of-life solar PV modules by combining the precision of laser technology with the efficiency of high-voltage pulses. The L&HVP method aims to maximize material recovery, particularly for delicate components such as silicon and metals, while minimizing the risk of degradation or contamination.

The novelty of the L&HVP method lies in its integration of two advanced techniques: laser irradiation for selective removal of the EVA encapsulant and high-voltage pulse crushing for targeted fragmentation and material separation. Laser irradiation ensures precise removal of the encapsulant without damaging the underlying materials. However, the application of High Voltage Pulse (HVP) crushing following EVA removal is critical for overcoming the limitations of conventional crushing and sorting methods. Conventional techniques often result in non-uniform particle sizes and contamination due to inefficient separation of components, such as silicon, glass, and metals. In contrast, HVP crushing leverages the dielectric properties of these materials, allowing for selective fragmentation and achieving higher recovery efficiency with minimal cross-contamination. This dual-stage process enhances the overall recycling performance, ensuring that delicate materials like silicon maintain their integrity and can be recovered at high purity.

The conceptual workflow of the proposed L&HVP technique is illustrated in Figure 22, outlining the sequential steps involved. The process begins with laser irradiation, which precisely removes the EVA encapsulant. Subsequently, high-voltage pulse crushing is applied to selectively fragment and separate key materials such as glass, silicon, and metals. By integrating these two techniques, the L&HVP method ensures both precision in encapsulant removal and efficiency in material separation, addressing the shortcomings of standalone methods.

Figure 22.

L&HVP Crushing Process.

This proposed workflow not only mitigates contamination risks but also demonstrates the potential for scalability and industrial application, subject to further experimental validation. While the L&HVP method is a conceptual framework, its potential advantages include enhanced material recovery, energy efficiency, and alignment with the principles of a circular economy. Future research will focus on experimental validation, optimization of process parameters, and addressing practical considerations such as equipment design and energy requirements.

6.1. Laser and High Voltage Pulse (L&HVP)

The L&HVP proposed technique integrates both laser irradiation and high voltage pulse crushing to achieve comprehensive recycling of waste solar panels. This innovative approach allows for the efficient recovery of valuable materials within a single processing unit, making it a highly effective solution for solar panel recycling.

6.2. How It Works

- Step 1: Removing the Parts:

- Prior to recycling, specific components are removed from the solar panels to prepare them for subsequent processing steps.

- Step 2: Laser Irradiation:

Laser irradiation is employed to facilitate the handling and disassembly of aged solar panels. The process provides two key benefits:

- Enhanced Component Separation: Lasers are used to sever connections between different components, making disassembly and material recovery more efficient.

- EVA Recovery: The laser effectively breaks the bonds within the ethylene-vinyl acetate (EVA) encapsulant, allowing for its easy extraction. Recovering EVA is crucial for sustainable recycling, as it can either be reused or safely disposed of.

- Step 3: High Voltage Pulse Crushing:

Following laser irradiation, high high-voltage pulse crushing is applied. This stage involves the controlled discharge of high-voltage pulses to dismantle and fragment the laser-treated materials. The energy from the pulses induces the breakdown of these materials into their individual components, facilitating efficient separation and recovery.

This combined L&HVP approach ensures the complete processing and recycling of solar panels, maximizing material recovery while minimizing waste.

7. Conclusions

This study provides a comprehensive analysis of various mechanical recycling methods for end-of-life solar photovoltaic (PV) panels, including Crushing, High Voltage Pulse Crushing, Electrostatic Separation, Hot Knife Cutting, Water Jet Cutting, and Magnetic Separation. Each method was evaluated for its effectiveness in recovering valuable materials such as glass, silicon, metals (copper, aluminum, silver, tin, lead), and EVA. The findings reveal that while each method has its strengths, none is fully capable of efficiently recovering all materials without significant limitations.

Crushing and High Voltage Pulse Crushing methods demonstrated strong performance in recovering glass and metals, but they struggle with efficiently separating EVA and maintaining the integrity of the materials. Electrostatic Separation is effective for isolating conductive materials but is less useful for non-conductive components like glass and EVA. Hot Knife Cutting excels at separating glass but does not address metal recovery. Water Jet Cutting is versatile but less effective at managing the EVA encapsulant. Magnetic Separation is limited to ferromagnetic materials, which are less relevant in PV panel recycling.

To address these challenges, the study proposes a hypothetical hybrid method, Laser and High Voltage Pulse (L&HVP), which integrates the strengths of laser irradiation and high voltage pulse crushing. Laser irradiation effectively removes the EVA encapsulant without damaging underlying materials, allowing for subsequent high high-voltage pulse crushing to efficiently separate and recover glass, silicon, and metals. While the L&HVP method is currently theoretical, its design is based on data-driven insights from the limitations of existing techniques.

The L&HVP method offers a promising solution for optimizing material recovery and enhancing the sustainability of solar PV module recycling. By addressing the shortcomings of conventional methods, this approach aligns with the principles of the circular economy, contributing to the responsible management of solar PV waste. Future research should focus on the experimental validation of the L&HVP method, exploring its practical applications, scalability, and economic feasibility in the context of large-scale PV recycling operations. The successful implementation of this hybrid technique could significantly advance the field of solar PV recycling, paving the way for more efficient and sustainable practices.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.A.; methodology, A.A.; formal analysis, A.A. and M.S.; investigation, A.A., S.A. and S.A.Q.; resources, A.A.; data curation, M.W.K. and A.A.; writing original draft preparation, A.A.; writing—review and editing, S.A. and M.T.I.; project administration. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors would like to express their profound gratitude to King Abdullah City for Atomic and Renewable Energy (K.A. CARE) for their financial support in accomplishing this work. As well as the Interdisciplinary Research Center for Sustainable Energy Systems (IRC-SES), King Fahd University of Petroleum and Minerals, under project No. INRE2105.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their profound gratitude to King Abdullah City for Atomic and Renewable Energy (K.A. CARE) for their financial support in accomplishing this work. As well as Interdisciplinary Research Center for Sustainable Energy Systems (IRC-SES), King Fahd University of Petroleum and Minerals, under project No. INRE2105.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Alim, A.; Islam, M.T.; Rehman, S.; Qadir, S.A.; Shahid, M.; Khan, M.W.; Zahir, M.H.; Islam, A.; Khalid, M. Solar Photovoltaic Module End-of-Life Waste Management Regulations: International Practices and Implications for the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Sustainability 2024, 16, 7215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, M.S.; Rahman, K.S.; Chowdhury, T.; Nuthammachot, N.; Techato, K.; Akhtaruzzaman, M.; Tiong, S.K.; Sopian, K.; Amin, N. An overview of solar photovoltaic panels’ end-of-life material recycling. Energy Strateg. Rev. 2020, 27, 100431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Opstal, W.; Smeets, A. Circular economy strategies as enablers for solar PV adoption in organizational market segments. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2023, 35, 40–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Renewable Energy Agency. Global Renewables Outlook. 2020. Available online: https://www.irena.org (accessed on 1 October 2024).

- Ali, A.; Malik, S.A.; Shafiullah, M.; Malik, M.Z.; Zahir, M.H. Policies and regulations for solar photovoltaic end-of-life waste management: Insights from China and the USA. Chemosphere 2023, 340, 139840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA). End-Of-Life Management: Solar Photovoltaic Panels. 2016. Available online: https://www.irena.org/publications/2016/Jun/End-of-life-management-Solar-Photovoltaic-Panels (accessed on 1 October 2024).

- International Renewable Energy Agency. Renewable Energy Target Setting. 2015. Available online: https://www.irena.org/-/media/Files/IRENA/Agency/Publication/2015/IRENA_RE_Target_Setting_2015.pdf (accessed on 2 October 2024).

- Nain, P.; Kumar, A. Initial metal contents and leaching rate constants of metals leached from end-of-life solar photovoltaic waste: An integrative literature review and analysis. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2020, 119, 109592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulazzani, A.; Eleftheriadis, P.; Leva, S. Recycling c-Si PV Modules: A Review, a Proposed Energy Model and a Manufacturing Comparison. Energies 2022, 15, 8419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Pero, F.; Delogu, M.; Berzi, L.; Escamilla, M. Innovative device for mechanical treatment of End of Life photovoltaic panels: Technical and environmental analysis. Waste Manag. 2019, 95, 535–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paiano, A. Photovoltaic waste assessment in Italy. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2015, 41, 99–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiandra, V.; Sannino, L.; Andreozzi, C. Photovoltaic waste as source of valuable materials: A new recovery mechanical approach. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 385, 135702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, D.; Saraf, A.K.; Rathee, N.S. Assessment of PV waste generation in India. Mater. Today Proc. 2023, 258053832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Divya, A.; Adish, T.; Kaustubh, P.; Zade, P.S. Review on recycling of solar modules/panels. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2023, 253, 112151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sah, D.; Chitra; Kumar, S. Investigation and recovery of copper from waste silicon solar module. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2023, 296, 127205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Feng, Y.; He, Y. The research progress on recycling and resource utilization of waste crystalline silicon photovoltaic modules. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2024, 270, 112804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.-J.; Liao, Q.; Xu, H. Anticipating future photovoltaic waste generation in China: Navigating challenges and exploring prospective recycling solutions. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2024, 106, 107516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hei, K.K.; Savaget, P.; Fukushige, S.; Halog, A. The Necessity for End-of-Life Photovoltaic Technology Waste Management Policy: A Systematic Review. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 461, 142497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, V.; Figueiredo, A.M.R.; Espejo, M.M.D.S.B. Challenges and strategies for managing end-of-life photovoltaic equipment in Brazil: Learning from international experience. Energy Policy 2024, 188, 114091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aşkın, A.; Kılkış, Ş.; Akinoglu, B. Recycling photovoltaic modules within a circular economy approach and a snapshot for Türkiye. Renew. Energy 2023, 208, 583–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.-H.; Chen, W.-S.; Lee, C.; Wu, J. Comprehensive Review of Crystalline Silicon Solar Panel Recycling: From Historical Context to Advanced Techniques. Sustainability 2023, 16, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, G.; Zhang, M.; Sun, Z.; Zhao, P.; Zhang, B. Recycling technology of end-of-life photovoltaic panels: A review. Energy Sources Part A Recover. Util. Environ. Eff. 2023, 45, 10890–10908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheema, H.A.; Ilyas, S.; Kang, H.; Kim, H.-J. Comprehensive review of the global trends and future perspectives for recycling of decommissioned photovoltaic panels. Waste Manag. 2023, 174, 187–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, J.; Kim, K.; Sohn, J.W.; Jang, H.; Lee, H.S.; Kim, D.; Kang, Y. Review on Separation Processes of End-of-Life Silicon Photovoltaic Modules. Energies 2023, 16, 4327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tembo, P.M.; Subramanian, V. Current trends in silicon-based photovoltaic recycling: A technology, assessment, and policy review. Sol. Energy 2023, 259, 137–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trivedi, H.; Meshram, A.; Gupta, R. Recycling of photovoltaic modules for recovery and repurposing of materials. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2023, 11, 109501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Tian, X.; Chen, X.; Ren, L.; Geng, C. A review of end-of-life crystalline silicon solar photovoltaic panel recycling technology. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2022, 248, 111976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhawan, N.; Agrawal, S. Recycling of discarded photovoltaic solar modules for metal recovery. Mining Metall. Explor. 2022, 39, 2539–2550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, M.S.; He, D.; Tiong, J.S.M.; Hanson, S.; Yang, T.C.-K.; Tiong, T.J.; Pan, G.-T.; Chong, S. Experimental, economic and life cycle assessments of recycling end-of-life monocrystalline silicon photovoltaic modules. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 340, 130796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Hasanuzzaman, M.; Rahim, N.; Amin, N.; Adzman, N.N. Global Challenges and Prospects of Photovoltaic Materials Disposal and Recycling: A Comprehensive Review. Sustainability 2022, 14, 8567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, R.; Zhuo, Y.; Shen, Y. Recent progress in silicon photovoltaic module recycling processes. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2022, 187, 106612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granata, G.; Altimari, P.; Pagnanelli, F.; De Greef, J. Recycling of solar photovoltaic panels: Techno-economic assessment in waste management perspective. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 363, 132384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.-Q.; Lai, D.; Wang, W.; Wang, Y. A systematically integrated recycling and upgrading technology for waste crystalline silicon photovoltaic module. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2022, 182, 106284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theocharis, M.; Pavlopoulos, C.; Kousi, P.; Hatzikioseyian, A.; Zarkadas, I.; Tsakiridis, P.E.; Remoundaki, M.; Zoumboulakis, L. An Integrated Thermal and Hydrometallurgical Process for the Recovery of Silicon and Silver from End-of-Life Crystalline Si Photovoltaic Panels. Waste Biomass Valorization 2022, 13, 4027–4041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Wang, Z.; Liu, C.; Wang, D.; Li, G.; Chen, X.; Qian, G.; Hu, K. A Green Method to Separate Different Layers in Photovoltaic Modules by Using Dmpu as a Separation Agent. SSRN Electron. J. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Khawad, L.; Bartkowiak, D.; Kümmerer, K. Improving the end-of-life management of solar panels in Germany. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2022, 168, 112678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.-Q.; Lai, D.; Wang, G.; Wang, Y. Nondestructive silicon wafer recovery by a novel method of solvothermal swelling coupled with thermal decomposition. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 418, 129457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobra, T.; Vollprecht, D.; Pomberger, R. Thermal delamination of end-of-life crystalline silicon photovoltaic modules. Waste Manag. Res. 2021, 40, 96–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, P.; Schmidt, L.; Lunardi, M.M.; Chang, N.L.; Spier, G.; Corkish, R.; Veit, H. Comprehensive recycling of silicon photovoltaic modules incorporating organic solvent delamination—Technical, environmental and economic analyses. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2021, 165, 105241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, R.; Dias, P.; Lunardi, M.M.; Ji, J. A sustainable chemical process to recycle end-of-life silicon solar cells. Green Chem. 2021, 23, 10157–10167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, S.; Yan, Y.; Wang, Z.; Wang, D.; Li, S.; Ma, W.; Wei, K. Enhanced separation of different layers in photovoltaic panel by microwave field. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2021, 230, 111213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansanelli, G.; Fiorentino, G.; Tammaro, M.; Zucaro, A. A Life Cycle Assessment of a recovery process from End-of-Life Photovoltaic Panels. Appl. Energy 2021, 290, 116727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camargo, P.S.S.; Domingues, A.; Palomero, J.; Kasper, A.C.; Dias, P.; Veit, H. Photovoltaic module recycling: Thermal treatment to degrade polymers and concentrate valuable metals. Detritus 2021, 16, 48–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Feng, K.; Liu, X.; Wang, P.; Chen, W.; Li, J. Looming challenge of photovoltaic waste under China’s solar ambition: A spatial–temporal assessment. Appl. Energy 2021, 307, 118186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoudi, S.; Huda, N.; Behnia, M. Multi-levels of photovoltaic waste management: A holistic framework. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 294, 126252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Liu, H.; You, J.; Diao, H.; Zhao, L.; Wang, W. Back EVA recycling from c-Si photovoltaic module without damaging solar cell via laser irradiation followed by mechanical peeling. Waste Manag. 2021, 137, 312–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tembo, P.; Heninger, M.; Subramanian, V. An Investigation of the Recovery of Silicon Photovoltaic Cells by Application of an Organic Solvent Method. ECS J. Solid State Sci. Technol. 2020, 10, 025001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, R.; Chang, N.; Lunardi, M.M.; Dias, P.; Bilbao, J.; Ji, J.; Chong, C.M. Remanufacturing end-of-life silicon photovoltaics: Feasibility and viability analysis. Prog. Photovoltaics Res. Appl. 2020, 29, 760–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrell, C.; Osman, A.I.; Doherty, R.; Saad, M.; Zhang, X.; Murphy, A.; Harrison, J.; Vennard, A.S.M.; Kumaravel, V.; Al-Muhtaseb, A.H.; et al. Technical challenges and opportunities in realising a circular economy for waste photovoltaic modules. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2020, 128, 109911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, R.; Chang, N.; Ouyang, Z.; Chong, C. A techno-economic review of silicon photovoltaic module recycling. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2019, 109, 532–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Song, E.; Zhang, C.; Zhuang, X.; Ma, E.; Bai, J.; Yuan, W.; Wang, J. Pyrolysis-based separation mechanism for waste crystalline silicon photovoltaic modules by a two-stage heating treatment. RSC Adv. 2019, 9, 18115–18123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoudi, S.; Huda, N.; Alavi, Z.; Islam, M.T.; Behnia, M. End-of-life photovoltaic modules: A systematic quantitative literature review. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2019, 146, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azeumo, M.F.; Germana, C.; Ippolito, N.M.; Franco, M.; Luigi, P.; Settimio, S. Photovoltaic module recycling, a physical and a chemical recovery process. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2019, 193, 314–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strachala, D.; Hylský, J.; Jandova, K.; Vaněk, J.; Cingel, Š. Mechanical Recycling of Photovoltaic Modules. ECS Trans. 2017, 81, 199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Libby, C.; Shaw, S.; Heath, G.; Wambach, K. Photovoltaic Recycling Processes. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE 7th World Conference on Photovoltaic Energy Conversion (WCPEC) (A Joint Conference of 45th IEEE PVSC, 28th PVSEC & 34th EU PVSEC), Waikoloa Village, HI, USA, 10–15 June 2018; pp. 2594–2599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Yan, S.; Li, Y.; Wang, Z.; Tan, Y.; Li, J.; Xia, M.; Li, P. Recycling Si in waste crystalline silicon photovoltaic panels after mechanical crushing by electrostatic separation. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 415, 137908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagnanelli, F.; Moscardini, E.; Granata, G.; Atia, T.A.; Altimari, P.; Havlik, T.; Toro, L. Physical and chemical treatment of end of life panels: An integrated automatic approach viable for different photovoltaic technologies. Waste Manag. 2017, 59, 422–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nevala, S.-M.; Hamuyuni, J.; Junnila, T.; Sirviö, T.; Eisert, S.; Wilson, B.P.; Serna-Guerrero, R.; Lundström, M. Electro-hydraulic fragmentation vs. conventional crushing of photovoltaic panels—Impact on recycling. Waste Manag. 2019, 87, 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sim, Y.; Tay, Y.B.; Pham, H.K.; Mathews, N. A facile crush-and-sieve treatment for recycling end-of-life photovoltaics. Waste Manag. 2023, 156, 97–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghahremani, A.; Adams, S.D.; Norton, M.; Khoo, S.Y.; Kouzani, A.Z. Delamination Techniques of Waste Solar Panels: A Review. Clean Technol. 2024, 6, 280–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preet, S.; Smith, S.T. A comprehensive review on the recycling technology of silicon based photovoltaic solar panels: Challenges and future outlook. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 448, 141661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, P.; Yang, F.; Bai, Y.; Yan, G.; Sun, Z.; Zhao, H.; Zhang, B. Analysis and optimization of the selective crushing process based on high voltage pulse energy. Miner. Eng. 2022, 185, 107697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akimoto, Y.; Iizuka, A.; Shibata, E. High-voltage pulse crushing and physical separation of polycrystalline silicon photovoltaic panels. Miner. Eng. 2018, 125, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, M.; Li, J.; Xu, Z. Management strategies on the industrialization road of state-of- the-art technologies for e-waste recycling: The case study of electrostatic separation—A review. Waste Manag. Res. 2012, 31, 130–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, P.; Schmidt, L.; Gomes, L.B.; Bettanin, A.; Veit, H.; Bernardes, A.M. Recycling Waste Crystalline Silicon Photovoltaic Modules by Electrostatic Separation. J. Sustain. Metall. 2018, 4, 176–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Liu, X.; Yu, J.; Xu, C.; Wu, Y.; Senthil, R.A. An overview of the comprehensive utilization of silicon-based solid waste related to PV industry. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2021, 169, 105450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Souza, R.A.; Veit, H.M. Study of electrostatic separation to concentrate silver, aluminum, and silicon from solar panel scraps. Circ. Econ. 2023, 2, 100027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndalloka, Z.N.; Nair, H.V.; Alpert, S.; Schmid, C. Solar photovoltaic recycling strategies. Sol. Energy 2024, 270, 112379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.-Y.; Hsiao, J.-C.; Du, C.-H. Recycling of materials from silicon base solar cell module. In Proceedings of the 2012 38th IEEE Photovoltaic Specialists Conference, Austin, TX, USA, 3–8 June 2012; pp. 2355–2358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Kim, W.; Cho, N.; Lee, H.; Park, N. An eco-friendly method for reclaimed silicon wafers from a photovoltaic module: From separation to cell fabrication. Green Chem. 2016, 18, 1706–1714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, P.; Javimczik, S.; Benevit, M.; Veit, H. Recycling WEEE: Polymer characterization and pyrolysis study for waste of crystalline silicon photovoltaic modules. Waste Manag. 2017, 60, 716–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.-K.; Lee, J.-S.; Ahn, Y.-S.; Kang, G.-H. Efficient Recovery of Silver from Crystalline Silicon Solar Cells by Controlling the Viscosity of Electrolyte Solvent in an Electrochemical Process. Appl. Sci. 2018, 8, 2131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lunardi, M.M.; Alvarez-Gaitan, J.P.; Bilbao, J.I.; Corkish, R. A review of recycling processes for photovoltaic modules. Sol. Panels Photovolt. Mater. 2018, 30, 74390. [Google Scholar]

- Wahman, M.; Surowiak, A.; Berent, K.; Szymczak, P. Eco-efficient removal of polymer back sheet fraction and material separation from solar cell waste. Sol. Energy 2023, 264, 112085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiandra, V.; Sannino, L.; Andreozzi, C.; Corcelli, F.; Graditi, G. Silicon photovoltaic modules at end-of-life: Removal of polymeric layers and separation of materials. Waste Manag. 2019, 87, 97–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tammaro, M.; Rimauro, J.; Fiandra, V.; Salluzzo, A. Thermal treatment of waste photovoltaic module for recovery and recycling: Experimental assessment of the presence of metals in the gas emissions and in the ashes. Renew. Energy 2015, 81, 103–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahman, M.; Surowiak, A.; Ebin, B.; Berent, K. PV back sheet recovery from c-Si modules using hot knife technique. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2024, 276, 113067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- L. Xinology Co. Water Jet Cutting Machine: Introduction. Available online: http://www.xinology.com/Glass-Processing-Equipments-Supplies-Consumables/glass-cutting/water-jet-cutting/overview/overview.html (accessed on 1 June 2024).

- TMC. A Window of Opportunity Through Water Jet Cutting. Available online: https://www.tmcwaterjet.co.uk/news-blog/recycling-glass-a-window-of-opportunity-through-water-jet-cutting/ (accessed on 1 June 2024).

- Bellini, E. Water Jet Tech to Recover Glass from End-of-Life Solar Panels. Available online: https://www.pv-magazine.com/2023/01/20/water-jet-tech-to-recover-glass-from-end-of-life-solar-panels/ (accessed on 2 June 2024).

- WJS. Waterjet Cutting Turns Waste into Added Value. Available online: https://www.waterjetsweden.com/articles/waterjet-cutting-turns-waste-into-added-value (accessed on 2 June 2024).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).