Abstract

In the 20th anniversary year of the European Geopark Network, and 5 years on from the receipt of the UNESCO label for the geoparks, this research focuses on geotourism contents and solutions within one of the most recently designated geoparks, admitted for membership in 2013: the Sesia Val Grande UNESCO Global Geopark (Western Italian Alps). The main aim of this paper is to corroborate the use of fieldtrips and virtual tours as resources for geotourism. The analysis is developed according to: i) geodiversity and geoheritage of the geopark territory; ii) different approaches for planning fieldtrip and virtual tours. The lists of 18 geotrails, 68 geosites and 13 off-site geoheritage elements (e.g., museums, geolabs) are provided. Then, seven trails were selected as a mirror of the geodiversity and as container of on-site and off-site geoheritage within the geopark. They were described to highlight the different approaches that were implemented for their valorization. Most of the geotrails are equipped with panels, and supported by the presence of thematic laboratories or sections in museums. A multidisciplinary approach (e.g., history, ecology) is applied to some geotrails, and a few of them are translated into virtual tours. The variety of geosciences contents of the geopark territory is hence viewed as richness, in term of high geodiversity, but also in term of diversification for its valorization.

1. Introduction

Geotourism has been defined as “tourism that sustains or enhances the distinctive geographical character of a place - its environment, heritage, aesthetics, culture, and the well-being of its residents” (National Geographic Society, https://www.nationalgeographic.com/maps/geotourism/). In its updated concept, geotourism is rapidly emerging as a form of urban and regional sustainable development [1]. As Earth scientists involved in Alpine geological and geomorphological studies, we focused the diversity of physical characters in a geographical region of the Western Italian Alps for understanding their significance in terms of natural and cultural heritage, and their possible contributions to the development of a sustainable, environmental-friendly geotourism.

From this perspective, we analyzed several sites and areas of geological and geomorphological interests, particularly those with significant scientific, educational, cultural, or aesthetic value, which are collectively named geoheritage sites [2]. This term has been used widely to define geological features valuable to the society because of their uniqueness [3,4,5] either in terms of scientific value or educational purposes and tourism [6,7].

Even if geoheritage is a generic but descriptive term, it is based on an advanced and inclusive consideration of Earth’s landforms, materials, and processes, recalling the geodiversity concept. According to Gray’s [8] definition, geodiversity is not just a matter of different features, but also of their assemblages, structures, systems, and contribution to landscapes. The complexity of geodiversity is a challenge for its study, but also an opportunity to be explored for the possible recognition of geoheritage sites and the establishment of tourist destinations for providing local and regional economic benefits [9,10].

As geodiversity represents a basis for the geotourism, it can be considered an important resource for the local and regional development [11]. Therefore, for the effective enhancement of geotourism, we considered both its geological and territorial dimensions:

- “landscape, interaction and time”: the geodiversity deeply contributes not only to the structure of a geographical area, but also to its cultural meaning and to its perception by people, either within natural or urban areas [12,13]. As a result, the landscape character derives from the action and interaction of natural and/or human factors (European Landscape Convention of Firenze; [14]) and their historical changes [15];

- “territorial dimensions of geodiversity and geoheritage”: within a territory, legal and economic issues related to the protection, preservation, and exploitation of geoheritage also have to be considered [8,16]. A comprehensive, integrated approach to the management of any natural heritage should be addressed, for combining directions from international, national, and regional laws and for stimulating a balance between the need to protect and enhance the natural heritage and the legitimate needs of local populations or visitors [17].

Such a comprehensive approach can offer relevant contributions to both geotourism activities and sustainable use of georesources (including hydro-georesources, sensu Perotti et al. [18]). Significant, long-lasting, international experiences are available for enhancing geotourism. A European Working Group for Earth Sciences Conservation (EWGES) was created in 1988, then (1993) transformed in the ProGEO association (http://www.progeo.se), devoted to diffusion of activities on Earth Sciences and to the establishment of an international network for geosite inventory and conservation. A similar working group was created within the International Union of Geoscience (IUGS), whose outreach activities were the “Geosites” (global inventory of sites of geological interest) and “Geoparks” (a UNESCO partnership for promoting territories including geosites). This site-based approach has worked extremely well for geoconservation purposes [19,20], although geosites cannot by themselves maintain and enhance geodiversity. If complemented by a “regional geothematic” approach, however, the benefits to geoconservation can be enormous. This approach encompasses a targeted selection of sites to create areas of outstanding value within a certain region, based on the attractiveness of scientific knowledge and the possibility of the sustainable fruition of both cultural and natural heritage [21]. The targeted selection of sites within geothematic areas makes easier efforts of regional geodiversity enhancement through careful planning of investments for local activities such as geotourism. In fact, as schematized by Brilha [22], geodiversity sites (on-site; in-situ) and geodiversity elements (off-site; ex-situ) could be selected as representative of the geodiversity of a region, and when they are recognized as being of relevant scientific value, they become geosites (on-site; in-situ) or geoheritage elements (off-site; ex-situ) within the wider context of the geoheritage.

An ideal methodological framework for making geotourism effective could be one devoted to the creation of material and virtual field trips aimed to raise awareness of the importance of our geoheritage, and the need to conserve it, amongst different actors: teachers and students, decision makers and stakeholders, entrepreneurs and the general public [23].

The importance of fieldtrips has been underlined since a long time having the function of a “direct experience with concrete phenomena and materials” [24]. When fieldtrips are then intended for schools, moreover, a learning-by-doing approach is favored, including the activity of “observation, identification, measurements and comparison” [24,25,26]. Bollati et al. [27], for example, proposed a multidisciplinary approach to physical landscape reading, based on the use of vegetation, to reconstruct the evolution of landforms (i.e., dendrogeomorphology) along a geotouristic itinerary. This kind of approach towards physical landscape evolution under geomorphic processes action, and its different responses according to geodiversity, could also be useful to people for hoping to gain awareness of Earth as a complex system, whose dynamics may induce hazards and risks [27,28,29]. If these experiences are then proposed in iconic sites (i.e., geosites of national or international relevance; [30]) they acquire even more efficacy.

Digital tools—geo-information, geo-visualization, digital monitoring, and Geographic Information Systems (GIS)—are allowing new approaches to geoheritage assessment and mapping [31,32], and geotourism communication and education [28,33]. Direct interactions between institutions and users, and the general public or schools, are enhanced, and favored on a worldwide scale [34]. Digital tools applications for key geoheritage areas are rapidly evolving, and there are several examples [32,34,35,36,37].

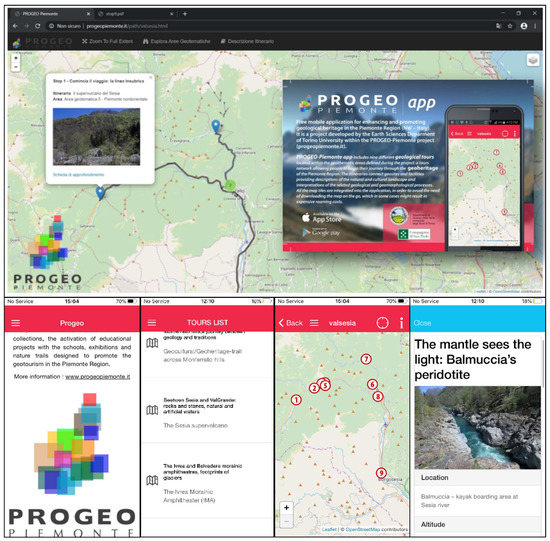

An important innovation is that many areas are expanding their reach to a global audience by the use of mobile apps, that are set for running on small, wireless devices, such as smartphones and tablets, rather than desktop or laptop computers. A mobile app can provide navigation aid in general, or can be made specific to a park or other protected area, to provide users with real-time guidance and knowledge as they either explore in the field, or virtually navigate the area at home [38]. Some protected areas provide physical or digital visitors with specialized apps equipped with a virtual park ranger or specialist as storyteller, offering particular views on trails. For example, the PROGEO Piemonte project [23,39] has developed two mobile apps devoted to exploring specific areas in the Western Italian Alps [40]. In the last few decades, moreover, the possibility to instantly share events and news and cross-posting between many platforms at the same time [34], is the favored dissemination of information among people, as it allows them to share their opinions and rate their experiences visiting different sites.

The aims of the paper are, hence, to: (i) illustrate the geodiversity of the territory of the Sesia-Val Grande UNESCO Global Geopark (Western Italian Alps) by means of on-site and off-site geoheritage (sensu Brilha [22]); (ii) to propose different approaches to geoheritage valorization, depending on the features of each specific area, using examples of fieldtrips and virtual tours as container of on-site and off-site geoheritage from the Sesia-Val Grande UNESCO Global Geopark.

2. Study Area

2.1. Location

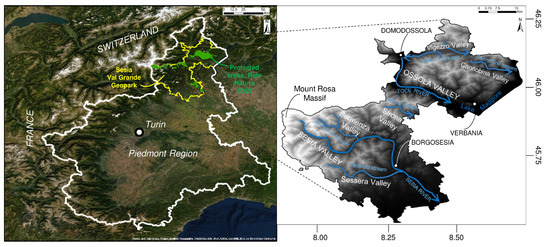

The Sesia-Val Grande UNESCO Global Geopark (SVUGG) is located on the north-east of the Piemonte Region (NW Italy), and encompasses areas of the Verbano-Cusio-Ossola, Biella, Novara and Vercelli Provinces (Figure 1). It is bordered to the west by the Monte Rosa massif, to the north by the Ossola and Vigezzo Valleys towards the Swiss border, to the south-east by Lake Maggiore and, to the south, by an area degrading towards the Po plain. The SVUGG includes, in the north, the whole Val Grande National Park and surrounding territories and, in the south, most of the mountain range of the Sesia river basin, including the whole Sesia Valley, and portions of neighboring territories, such as Valsessera, and Strona Valley.

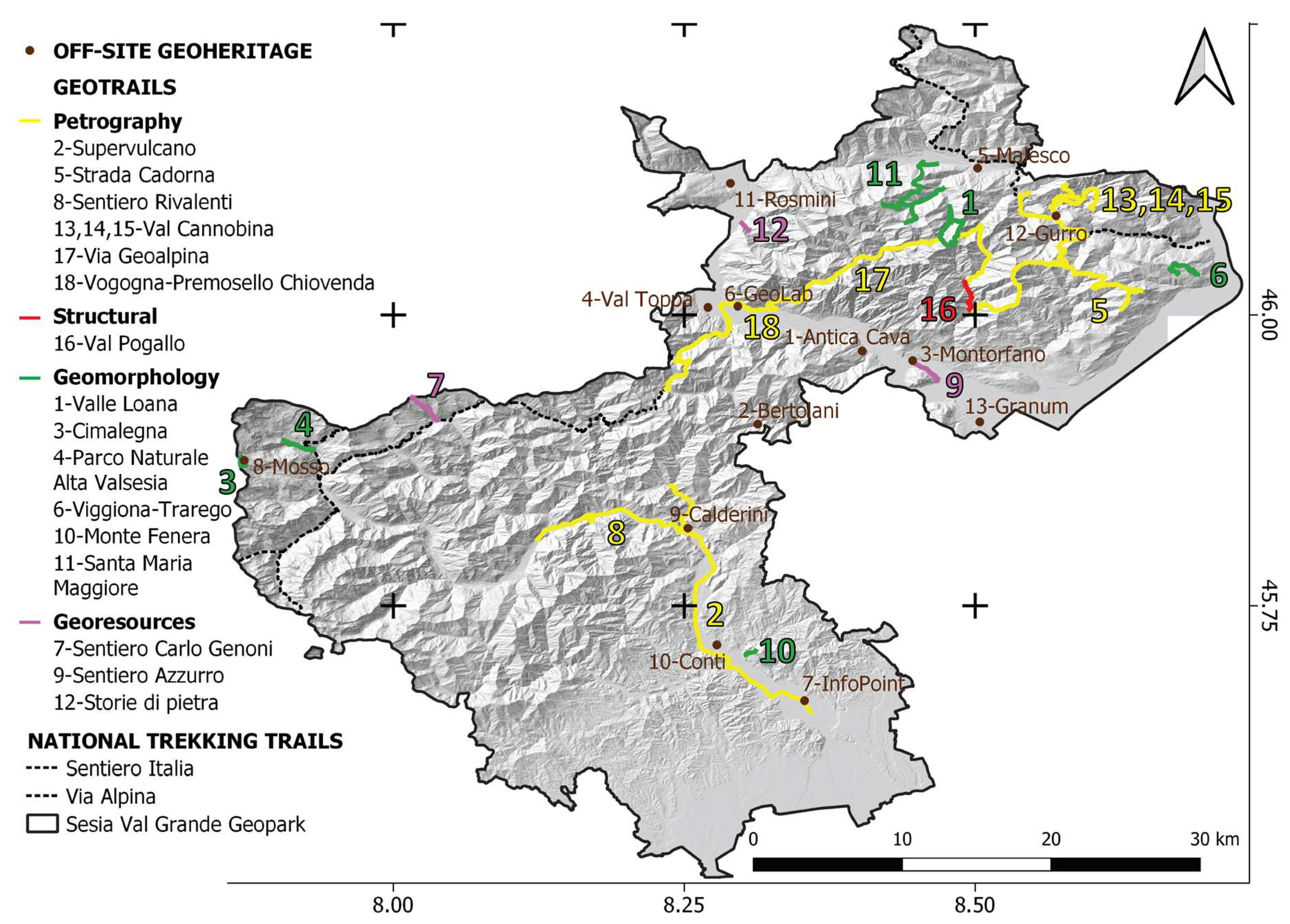

Figure 1.

Geographical location of the Sesia-Val Grande UNESCO Global Geopark. On the left, the position of the SVUGG within the Piemonte Region with the protected area’s location; on the right, the Digital Terrain Model (5 m resolution, source Geoportale Regione Piemonte; http://www.geoportale.piemonte.it/geocatalogorp/?sezione=catalogo) highlighting the articulation of the relief in the geopark with the main streams, lakes, and peaks.

2.2. The Sesia-Val Grande UNESCO Geopark History

The Sesia Val Grande UNESCO Global Geopark (SVUGG) is member of the European Geopark Network (EGN) since 2013, and of the UNESCO Global Geoparks Program-UGGP since November 2015. It covers an area of about 2202 km2 and has a perimeter of around 423 km.

The Val Grande National Park (www.parcovalgrande.it), the first partner of the geopark and entirely located within the geopark, was established in 1992 by the decree of the Italian Environment Ministry. It is recognized as the largest wilderness area in Italy, but also in Europe, and since its creation it protects both habitats and endangered animal and botanical species. The National Park was also established as a Site of Community Importance (SCI) and a Special Protection Zone (SPZ) of the Natura 2000 network, because it preserves 10 priority habitats in its territory. Since 2007, the geological heritage also became a strategic target of the activities in the Park, finally leading to its candidature for the European Geopark Network (EGN).

The second partner of the geopark is the Geotouristic Association of the Valsesia Supervolcano (www.supervulcano.it/home.html), which represents the area of the Sesia Magmatic System (middle and lower Sesia Valley), and includes among its members two Natural Parks: Monte Fenera and Alta Valsesia.

The SVUGG comprises other protected areas as the Natural Park of the Alta Val Strona, the Natural Reserves of Baragge and Fondo Toce, the Special Reserves (UNESCO Heritage Sites) of Ghiffa, Varallo, and Domodossola Sacri Monti, as well as other protected areas (Oasi Zegna, Oasi Bosco Tenso, and Pian dei Sali).

The SVUGG has a website (http://www.sesiavalgrandegeopark.it/) and a social network page where updates on events and initiatives are available (https://www.facebook.com/pg/AssociazioneSesiaValGrandeGeopark/posts/).

As a whole, the territory of the geopark offers its visitors the opportunity to observe the effects of geologic processes, which formed the continental crust at different depths. It also introduces them to the concepts of global plate tectonics, as it is located astride the Insubric Line, representing a major alpine lineament that marks the boundary between the Central Alps, consisting of intricate refolded basement nappes, and the Southern Alps with S-vergent thrusts [41].

Since the geopark extends from the Monte Rosa massif to the northern boundary of the Po Plain, it also shows the record of past climate changes and of the glacial, periglacial, water- and gravity-related processes, which continuously shape the landscape [42].

Last but not least, the geopark territory is also an open-air museum of the ancient civilization of the Alps, since it preserves the traces of a “stone culture” of different ages: from the Paleolithic human settlements in the Monte Fenera caverns, up to the historical use of local georesources, and the construction of defense works in World War I, by taking advantage of the landscape morphology.

Some research projects devoted to the dissemination of Earth Sciences among schools and general public had the SVUGG as focus area. The most important ones are:

- -

- The ERASMUS+ Project “GEOclimHOME: Geoheritage and climate change discovering the secrets of home” (https://geoclimhomeblog.wordpress.com/). This is a three-year project funded in 2015 by the Erasmus+ Programme within the Key Action 2 (cooperation for innovation and the exchange of good practices which promote strategic partnership for school education). It supports high school teaching and scientific research between Rokua (Finland) and Sesia-Val Grande (Italy) UNESCO Geoparks. It aims to improve both the general perception of climate and environmental changes in Europe and the appraisal of geoheritage. The project was implemented with the participation of the Chablais UNESCO Geopark (France).

- -

- The PROGEO-Piemonte Project (http://www.progeopiemonte.it/). This offers an innovative approach for the management and enhancement of the geological heritage of the Piemonte Region. Within the project, nine “geothematic areas” have been identified for representing the regional geodiversity of the Piemonte Region. Geological sites identification, the enhancement of museum collections, the activation of educational projects with the schools, the installation of exhibitions, and nature trails designed to promote the geotourism, by means of virtual tours and fieldtrips, are among its main aims. Its main actions concern: (i) the progress of scientific knowledge; (ii) land development, education, and communication through innovative methodologies; (iii) collaboration with the local communities in order to involve them and provide them with benefits.

- -

- SITINET – Geological and archeological sites of the Insubria Region. This was a project devoted to the inventory of the geological and archeological spots in the Insubria region, including the Ossola area (http://www.sitinet.org/). It ended in 2013, just during the acceptance of the study area in the EGN, which was also a starting point for the inventory of the geoheritage of the geopark.

Another relevant project currently ongoing in the SVUGG, and particularly related to the Val Grande National park territory, is the COMUNITERRAE - Maps of Cultural Communities of Alpine Landscapes in the Val Grande National Park (http://www.comuniterrae.it/). It is a project by the Associazione Ars.Uni.Vco and Val Grande National Park, included in the European Chart for Sustainable Tourism. It aims to promote innovative methods to ensure sustainable features, and to clearly communicate the project benefits both to the local and to a wider public. The valorization of assets, places, and components of the material and immaterial heritage of a territory along centuries is the main focus. In 2019 the project was awarded with the European Heritage Award 2019 in the category “Education, Training and Awareness-Raising”.

The different aspects of the geopark are then described in the following paragraphs.

2.3. Geology

The geologic context exposed in the SVUGG territory is of high scientific interest, as witnessed by thousands of papers published in the last 50 years by researchers from all over the world.

The geodiversity which characterizes the geopark results from processes lasted over 500 million years, whose effects are still recognizable in the field.

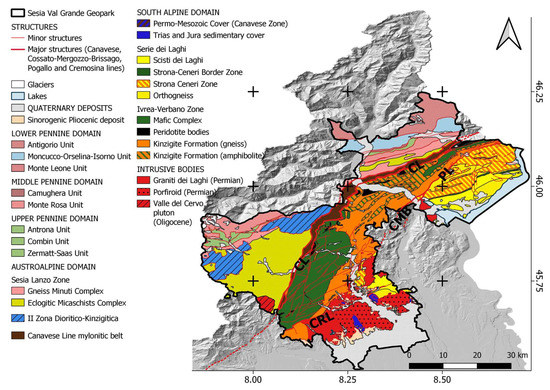

The SVUGG (Figure 2) is stretched along the Canavese Line (CL), a segment of the Insubric Line, a major tectonic boundary separating the N-vergent nappes of the Central Alps (Austroalpine and Pennine domains), affected by the Alpine metamorphism, from the S-vergent South Alpine domain [43] (to the SE), a pre-Alpine metamorphosed basement with its sedimentary coverage.

Figure 2.

Regional Geological setting of the Sesia-Val Grande UNESCO Global Geopark from the ARPA Piemonte Geological map (1:250000) (modified from https://webgis.arpa.piemonte.it/geoportale/).

Most of the territory of the geopark (Figure 2) belongs to the South Alpine domain. Along the CL, which crosses the area in SW–NE direction, the alpine units are represented by the Austroalpine domain, whereas the other nappes (Lower, Middle and Upper Pennine domains) crop out only along the north-western boundary of the geopark.

Therefore, the South Alpine domain and its relations with the Austroalpine domain along the CL are the focus of most of the geotouristic activities proposed to the general public along geotrails, in exemplary geosites (see Section 4.1 and Section 4.2), as well as in different thematic museums and laboratories (see Section 4.3). The main geological themes will be described in the following paragraphs.

2.3.1. The Canavese Line

The Canavese Line (CL) (sensu Schmid et al. [44] and Steck et al. [41]) here represents the contact between the Austroalpine domain, to the north-west, involved in the Alpine metamorphism, and the South Alpine domain, to the south-east, which preserves much older structures, despite having experienced some Alpine tectonic deformation in greenschist to anchizonal facies [45].

The Austroalpine domain is here represented by the Sesia-Lanzo Zone, a composite unit (Gneiss minuti and Eclogitic Micaschists Complexes) with a polyphase deformation history (HP/LT; mainly blue-schist to eclogite facies conditions; [46,47]) related to specific phases of the Alpine orogeny (Late Cretaceous–Early Tertiary), and by the II Dioritic-Kinzigite Zone, characterized by micaschists, gneisses, and metabasites in granulite to amphibolite facies [48].

The CL is visible on the field as a greenschist facies mylonite belt [41], up to 1 km thick, which may involve rocks belonging to:

- i.

- The northern border of the Ivrea-Verbano Zone (South Alpine basement), with its Permo-Mesozoic cover;

- ii.

- The Canavese zone (South Alpine domain; [49]), consisting of amphibolite facies basement rocks overlain by Permian silicoclastic sediments and Triassic-Liassic carbonate rocks (sedimentary and metamorphic); the latter were accreted to the Ivrea-Verbano Zone margin, before the Alpine metamorphic greenschists facies overprint and are regarded as the distal continental margin of the Adria plate facing the Ligurian–Piedmont Ocean [49];

- iii.

- The southern border of the Sesia-Lanzo Zone (Austroalpine domain) [44], well exposed in the Ossola Valley.

In the Loana Valley, near the northern boundary of the Val Grande National Park, the mylonite occurrence (i.e., the Scaredi Formation [41]) is particularly meaningful [44,50,51,52]. There, mylonites derived from the Permo-Mesozoic cover rocks are dismembered, and often imbricated with or folded into the Ivrea-Verbano-derived mylonites; Sesia-Lanzo mylonitized gneiss also occur along restricted bands [49].

2.3.2. The South Alpine Domain

In the SVUGG area, the South Alpine domain is represented by the Massiccio dei Laghi [53,54], which comprises two main lithotectonic units: The Ivrea-Verbano Zone and the Serie dei Laghi. After Ferrando et al. [49], it also comprises the Canavese Zone (see before).

The Massiccio dei Laghi exposes a spectacular cross section from the lower crustal levels of the Ivrea-Verbano Zone to the middle and upper crustal levels of the Serie dei Laghi. It is considered a model for a magmatically underplated and extended crustal section [55,56].

The Ivrea-Verbano Zone mainly consists of two portions:

- i.

- The Kinzigite Formation: a metamorphosed volcano-sedimentary sequence, composed of dominant metapelites, with minor quartzites, thin meta-carbonate horizons and interlayered metabasites [57]. Mantle peridotite lenses are tectonically interfingered with the metasedimentary rocks [58], especially in the north-western part, near the CL (Balmuccia in the Sesia Valley, Premosello in the Ossola Valley and Finero in the Cannobina Valley: [59] and references therein). The metamorphic grade decreases from the granulite facies in the northwest to the upper amphibolite facies in the southeast [60].

- ii.

- The Mafic Complex: gabbroic to dioritic intrusive rocks, representing the deepest level of the Sesia Magmatic System (described below).

The scientific importance of the Ivrea-Verbano Zone is once more underlined by the recent Project Drilling the Ivrea-Verbano Zone (DIVE), which, through four drilling operations in the Sesia and Ossola Valleysaims to unravel the physico–chemical properties and architecture of the lower continental crust towards the crust–mantle (Moho) transition [61].

The Serie dei Laghi [54] consists of different units (from NW to SE):

- i.

- Strona-Ceneri Zone: this consists of two types of paragneisses. The Gneiss Minuti, fine-grained metasandstones still preserving relicts of sedimentary structures, and the Cenerigneiss, coarse-grained to conglomeratic gneisses containing a variety of enclaves (quartzite pebbles, nodules rich in aluminium silicates, fragments of metamorphic rocks). Both gneisses contain calc-silicate enclaves, deriving from calcareous concretions frequent in arenaceous deposits. Gneiss Minuti and Cenerigneiss are respectively interpreted as well sorted deposits from turbidity currents and as mass flow turbidites, deposited in an accretionary prism along an active continental margin [62,63].

- ii.

- Strona-Ceneri Border Zone [64]: a continuous horizon, one to several hundreds of meters thick, between the Strona-Ceneri Zone and the Scisti dei Laghi. It mainly consists of banded amphibolites, with lenses of ultramafites, metagabbros, garnet bearing amphibolites (retrogressed eclogites) and minor paragneisses. The banded amphibolites are an example of the Leptynite-Amphibolite Group (LAG), an association widespread throughout the Hercynian belt in Europe. The LAG is formed by tuffites of alternate mafic and acidic composition deposited in a marine environment [65].

- iii.

- Scisti dei Laghi: mainly garnet and staurolite and kyanite micaschists, with minor paragneiss intercalations.

Thick Orthogneiss lenses are intercalated in all these units, but mainly within or close to the Strona-Ceneri Border Zone. They are metaluminous tonalites to granites with calcalkaline affinity ([66,67] and references therein) and an Ordovician intrusion age around 466 Ma (Rb-Sr whole rock isochron; [68]).

The intrusives and their sedimentary host rocks suffered together the Variscan orogenic metamorphism, mainly in amphibolite facies conditions, recorded by mineral ages of 311–325 Ma [67].

The original contact between the Ivrea-Verbano Zone and Serie dei Laghi is the Cossato-Mergozzo-Brissago Line (CMB; [69]), an important subvertical tectonic lineament characterized by the simultaneous occurrence of three distinctive features [53]: high-T mylonites, migmatites, and mafic to intermediate dykes and stocks (called the “Appinite Suite” [69]), mostly concordant with the CMB mylonitic foliation. The best estimate of the intrusion age of the Appinites is a U-Pb age of 285 ± 5 My [70] on a monazite from a dyke near Mergozzo. The CMB is cut at low angle and dislocated by the Pogallo Line [53], characterized by amphibolite to greenschist facies mylonites and by the lack of Appinite intrusions. In the Sesia sector, the CMB has been reactivated by a younger fault (Cremosina Line; CRL) [53].

The last large-scale event in the Serie dei Laghi was the intrusion of granitic magmas forming different plutons (Graniti dei Laghi) outcropping along the southeastern border of the SVUGG. The most famous of them are the Montorfano and Mottarone–Baveno plutons (dated at 275 Ma [67]).

2.3.3. The Sesia Magmatic System

The Sesia Magmatic System is part of a large Late Carboniferous to Early Permian igneous province [71], a bimodal suite of basic and silicic volcanic and plutonic rocks outcropping across Europe from Spain to Scandinavia in association with extensive crustal rifting. From the lower to the upper levels, it consists of:

- i.

- The Mafic Complex (part of the Ivrea-Verbano Zone): this is an 8-km-thick composite layered intrusion (peridotites, pyroxenites, norites, and the main gabbro [72,73,74]), which intruded the deep crust around 288 Ma ago [75]. Along the intrusive contacts, partial melting of the kinzigites produced migmatites within 1 to 2 km from the intrusion [76]. Residual melt from the Mafic Complex and silicic melt generated by anatexis migrated to higher crustal levels.

- ii.

- The Valle Mosso granite: this is a compositionally zoned pluton [77] grading upwards into a fine-grained to granophyric facies with miarolitic cavities. It also contains some basaltic to andesitic dykes and intrudes the base of the overlying caldera.

- ii.

- The Sesia Supervolcano: this forms the upper part of the system, together with relicts of a bimodal volcanic field of basaltic andesite and rhyolite. The supervolcano, partially covered by younger sedimentary deposits, is a huge rhyolitic caldera with a diameter exceeding 15 km and an estimated volume of ignimbrite erupted above 300 km3 [78]. The caldera-forming events are well documented along the Sesia Valley and its hydrographic network, with beautiful exposures of volcanic megabreccia within the welded rhyolitic ignimbrite that fills the caldera, and huge blocks of country rocks (Scisti dei Laghi) slided into the caldera during the eruption. After Quick et al. [78], volcanism lasted approximately 6 My, beginning about 288 Ma and culminating in the caldera-forming eruption at about 282 Ma. The karstic Triassic marine carbonate of Monte Fenera is deposited on the caldera ignimbrite.

2.4. Geomorphology

From a geomorphological point of view, the Sesia Val Grande UNESCO Global Geopark (SVUGG) preserves several geomorphological landscapes tracing back to the long-term modelling history of the Alpine relief. A diversity of landforms recalls ancient and present surficial processes, which shaped the landscapes by means of their dynamic interactions with geological and tectonic conditioning factors. As a result, the altitudinal range of the whole SVUGG area is articulated and extreme: from the 4634 m a.s.l. of Monte Rosa to less than 200 m a.s.l. of the Po plain, down to the bottom of Lake Maggiore, a crypto-depression at −179 m. The Geomorphodiversity (sensu Panizza [79]) of the geopark is presented below, with references to both the geological constrains and the morphodynamic processes affecting the geomorphological landscape.

2.4.1. Lithostructural Constrains and Long-term Geomorphological History

The SVUGG area belongs to the Western Alps, an arch-shaped mountain chain which shows, at the regional scale, an asymmetrical transversal profile: the inner SE-facing side is shorter and steeper than the outer NW-facing side. Within the inner side of the Alps (Figure 1), the SE-NW altitudinal profile of the geopark shows morphological steps with distinctive mean elevation: from the upper plain (altitude between 200–350 m a.s.l.), to the foothills (350–1000 m a.s.l.) through all to the mountain relief (1000–4634 m a.s.l.) up the current alpine watershed [42].

At the regional scale, these distinctive morphological steps correspond roughly to the distribution areas of major geological complexes of the Western Alps, namely (from SE to NW): The Quaternary deposits of the Po plain and synorogenic Pliocene deposits, the sedimentary, magmatic, and metamorphic units of the South Alpine domain and the metamorphic units of the Austroalpine and Pennine domains (Figure 2) [80,81].

At the local scale, a diversity of peculiar relationships can be recognized between landforms and lithotypes. Some examples include: enhanced effects of differential erosion along the valleys, where schist units outcrop between massive magmatic or metamorphic rocks, (e.g., the morphological change corresponds to the narrow, deeply incised gorge of the Mastallone river within the hard diorites, while upstream of Fobello, a large valley developed, due to most erodible metamorphic schists); microscale competence contrasts between hard rock inclusions within pyroclastic breccias; subsurface karst landforms for dissolution phenomena of carbonatic rocks.

Moreover, strong conditioning factors to the geomorphological landscape are due to the geometrical setting of regional schistosity, to local geological structures, and to major tectonic discontinuities. At a regional scale, this is particularly evident along the shear zones related to the Canavese, Cossato-Mergozzo-Brissago, Pogallo and Cremosina Lines (Figure 2). As an example, the whole NE sector of the SVUGG is dominated by marked NE-SW (within Serie dei Laghi Unit) and NNE-SSW (within Ivrea-Verbano Unit) trends of morphostructures, either represented by deep incised tributary valleys (Figure 3b) and linear segments of the hydrographic network (Figure 3c).

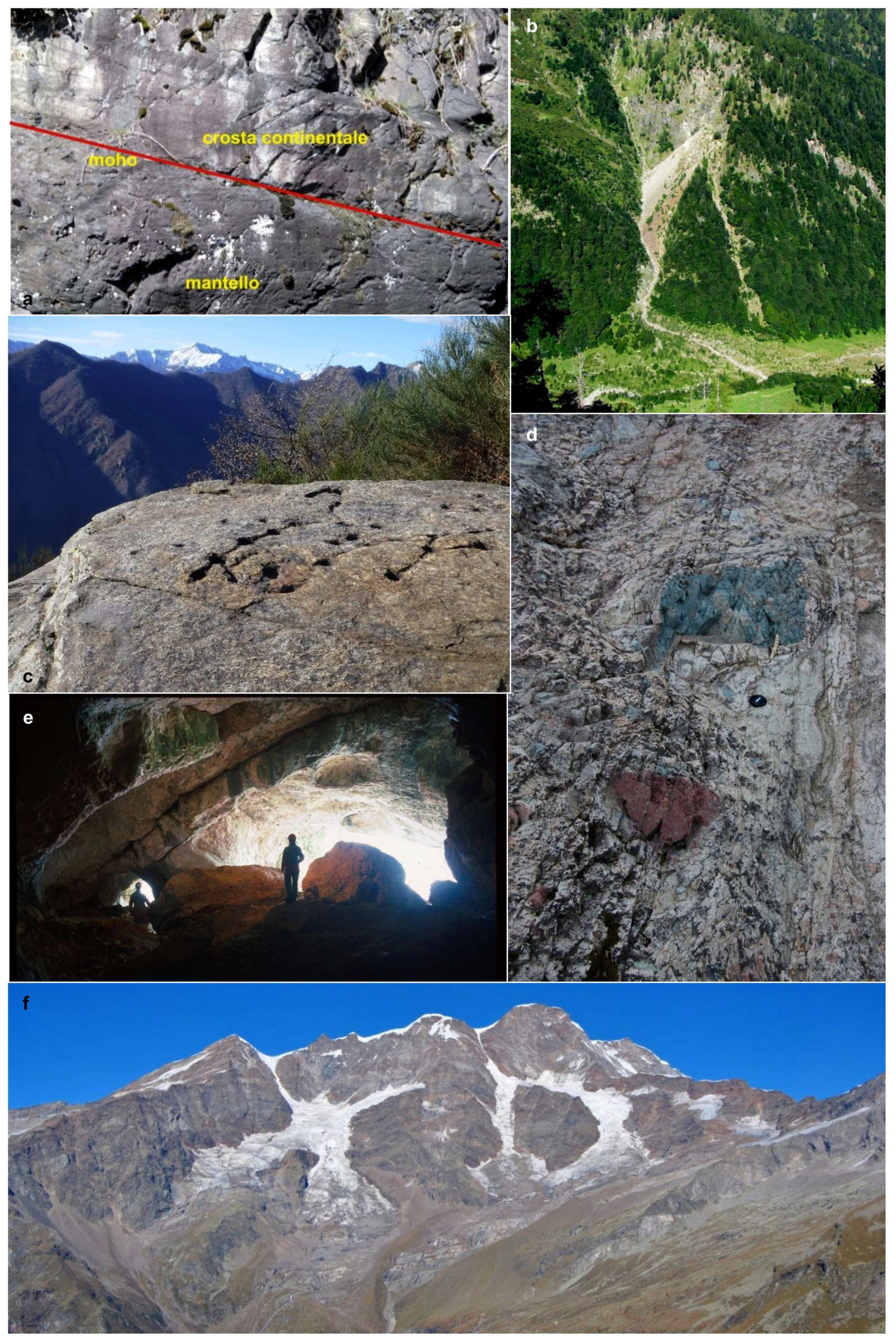

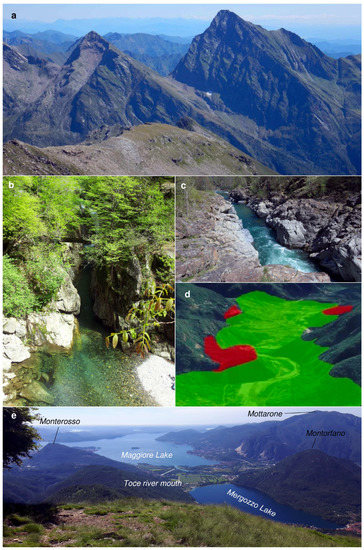

Figure 3.

Example of geomorphological features characterizing the Sesia Val Grande UNESCO Global Geopark: (a) Tagliaferro peak in Sesia Valley; (b) incised tributary stream of the Pogallo Valley; (c) linear stream at Balmuccia (Sesia Valley); (d) Unipiano and Sacro Monte di Varallo glacial terraces; (e) Toce river mouth in the Maggiore Lake, with the Montorfano peak on the right.

The alpine valleys across the Geopark develop radially from the Po Valley towards the watershed. The two major valleys (Sesia and Toce valleys) are deeply incised in the bedrock and their slopes sometimes exceed 3000 m a.s.l.. The engravings of these alpine valleys can be dated to the Messinian [82] or to the Pliocene [83]. This long-term geomorphological history is witnessed by landforms and deposits within the Geopark, such as the Lake Maggiore cryptodepression, the deep valleys and the foothills sector where marine sediments were deposited during the Pliocene [84]. This ancient modeling of the mountain chain was followed by the deposition of a continental regressive sedimentary sequence between the middle Pliocene and the lower Pleistocene (Villafranchiano; [84]).

Thereafter, following the climatic changes of Quaternary period, the entire Alpine sector of Sesia Val Grande was repeatedly occupied by important glacial masses. The glacial pulsations have shaped the main valleys of the area, strongly influencing the current geomorphological and hydrographic regional structure.

2.4.2. “Recent” and Present-day Geomorphological Landforms and Processes

Within an area of large geomorphodiversity, the SVUGG offers both a live demonstration of active glacial processes and a window on past climate changes recorded in the Pleistocene landforms, marked by repeated glacial advances and retreats.

The onset of Quaternary glaciations in the Western Alps led to the formation of a large ice sheet, and major valley glaciers [85]. Within the geopark, both erosional and depositional landforms witness the extent of major Pleistocene glacial modelling phases from the Monte Rosa massif to the Sesia and Ossola Valleys. Starting from the higher elevation areas, erosional landforms such as magnificent nunatak-like mountains are visible (e.g., Mud Horn and Tagliaferro peak, high Sesia Valley, Figure 3a), large and steep U-shaped valleys (e.g., Toce Valley, Figure 3e), as well as trimlines and in-valley sequences of erosional and depositional landforms (e.g., the Unipiano and Sacro Monte di Varallo glacial terraces, examples of further valley deepening after glacial erosional modelling, Figure 3d).

Distinctive depositional features all around the Maggiore Lake witness the Toce and Ticino glaciers extension to the upper Po plain through the Verbano lobe and towards the Orta lake [86] leaving few areas free of ice cover, such as Monte Mottarone, SW of Verbania. According to geomorphological evidences, radiocarbon datings, and numerical models [87,88,89]; also, the Pogallo Valley was supposedly indicated as of incomplete glacial coverage during the Late Glacial Maximum (LGM, around 24ky BP, in the geopark area), thus making possible survival of older structural and fluvial landforms.

Successively, during the Little Ice Age (LIA, XIV-XIX century), favorable climatic conditions allowed local glacier expansion. Later, SVUGG glaciers experienced a strong retreat; from the end of the LIA until now, they lost about the 50% of their area (from about 7 km2 to about 3.5 km2, [90,91]). Currently, according to the New Italian Glacier Inventory [92] only seven glaciological units exists on the slopes of the Monte Rosa southeast side: four glaciers and three snowfields. As a result of the ongoing climate change, their shrinkage is still underway.

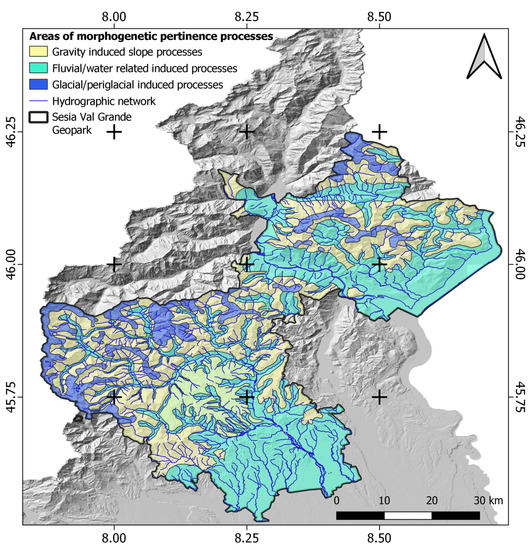

The possible appraisal of several environmental changes through time as a consequence of glacial, periglacial, water- and gravity-related processes, is among the most attractive characters of the geomorphological heritage in the geopark. A thematic representation of the SVUGG geomorphological landscapes is offered in Figure 4, which is a land-systems map created as a factor map for regional assessment of geodiversity within the geopark. GIS synthesis and interpretation of regional datasets with geomorphological contents (hydrography, glaciers, glacial cirques and periglacial features, landslides, debris-flows, and alluvial fans) allowed the recognition of areas characterized by prevalence of a certain type of landforms and related processes. These are useful for regional enhancement of geomorphodiversity and framing of local geosites.

Figure 4.

A land-systems map created as a factor map for regional assessment of geodiversity within the Sesia Val Grande UNESCO Global Geopark.

As shown in the map, a large area of the geopark is characterized by the hydrographic basins of two main rivers (Sesia and Toce) and by slopes providing several insights on the effects of water-related processes. The selection of geosites and geotrails concerning fluvial and water related landforms and processes, that could also affect their evolution (e.g., [93,94]), is of great importance for the enhancement of SVUGG geoheritage. This particular aspect of geodiversity (i.e., hydro-geodiversity sensu Perotti et al. [18]), in fact, includes several abiotic ecosystem services that have been recognized of high relevance for the local community, either for their material contents, for the provisioning character (water for human and agricultural consumption and for renewable energy), or for their valuable contribution to cultural and leisure activities (environmental education, tourism, sports).

To complete this geomorphological framework, examples of karst morphologies (i.e., mainly hypogean caves) are also present where carbonatic rocks occur, such as in the Monte Fenera area.

2.5. Georesources and Ancient Human Settlements

Georesources within the geopark territory are strictly related to its high lithological geodiversity and morphological traits. These features are related to the abiotic ecosystem services (such as provisioning and cultural services, as outlined by Gray [8]).

Quarrying and mining were important economic activities in the geopark area and its vicinity for centuries, whereas, at present, all of the mines and most of the quarries are closed and the land rehabilitated, in some cases through geotouristic valorisation activities (see Section 4.3).

The Ossola Valley is one of the most important quarrying areas of the Italian Alps [95,96,97], materials are used since a long time all around the national territory and also abroad. Several web resources are available to explore this richness (http://www.pietredelvco.it/; http://pietredelcusio.weebly.com/).

The most relevant georesources for the local communities, in the portion of the Ossola Valley within the SVUGG territory, are:

- -

- The Permian Graniti dei Laghi: Mottarone-Baveno (Figure 5a), Montorfano, and Mergozzo quarries were active since the XVI century, and their pink, white, and green granites were extensively used in architecture outside the region [97,98].

Figure 5. Georesources providing abiotic ecosystem services to the community within and outside the Sesia Val Grande UNESCO Global Geopark: (a) Mottarone and Montorfano granite: on the left, a rocky chain in Rome city made of Montorfano white granite and the columns in Baveno pink granite; on the right, a view on the Baveno quarry with Montorfano quarry in the background; (b) the Cava Madre in Candoglia (on the left), exclusively reserved since 1387 AD for the Milan Cathedral on the right); (c) an outcrop with the traditional signs of Pietra ollare extraction (above) and a pot made of the same rock and conserved in the Ecomuseo ed leuzerie e di scherpelit (below, courtesy of Archivio Ecomuseo by Riccardo Rapini).

Figure 5. Georesources providing abiotic ecosystem services to the community within and outside the Sesia Val Grande UNESCO Global Geopark: (a) Mottarone and Montorfano granite: on the left, a rocky chain in Rome city made of Montorfano white granite and the columns in Baveno pink granite; on the right, a view on the Baveno quarry with Montorfano quarry in the background; (b) the Cava Madre in Candoglia (on the left), exclusively reserved since 1387 AD for the Milan Cathedral on the right); (c) an outcrop with the traditional signs of Pietra ollare extraction (above) and a pot made of the same rock and conserved in the Ecomuseo ed leuzerie e di scherpelit (below, courtesy of Archivio Ecomuseo by Riccardo Rapini). - -

- Carbonate metasedimentary rocks, dated back to Permian-Mesozoic, and marbles. The metacarbonates have a stripe-like distribution along the Canavese Line, within the Ivrea-Verbano and Canavese Zones. Especially in the Ossola Valley, they were used for lime production within the lime kilns (e.g., the Loana Valley [99]; SF 4-I). Marbles occurring as lenses within the Ivrea-Verbano kinzigites were extensively quarried as ornamental rocks since ancient times: the most famous quarry is the Cava Madre in Candoglia, exclusively reserved since 1387 AD for the Milan Cathedral (Duomo di Milano) (Figure 5b) [100].

- -

- Talc and/or chlorite-rich metamorphic rocks, deriving from mafic—ultramafic protoliths within the Austroalpine domain, locally known as “Pietra laugera” or “Pietra ollare”. They are “soft”, easily workable stones typically used for jars, pots, and pipes (Figure 5c) [101].

Concerning the human settlements in the area, both in the Ossola Valley and in the Sesia Valley, there is evidence of human habitation dating back to the Paleolithic, as it would have had favorable environmental conditions. In the lower Sesia Valley, within the karstified Triassic marine carbonate complex of Monte Fenera, caverns utilized by Paleolithic inhabitants can be found [102]. Moreover, famous petroglyphs, carved into different lithologies, probably related to religious ceremonies, are located at the Alpe Sassoledo (Figure 6a), Alpe Prà, Alpe Pianzà (Figure 6b), and Malesco villages, in the Ossola Valley. In particular, the petroglyphs of the Alpe Sassoledo (Figure 6a) were the source of inspiration for the creation of the Val Grande National Park logo. Finally, remnants of an ancient necropolis ascribed to the Leponti population (II-I century BC) were found near Ornavasso [103].

Figure 6.

The (pre)historical background signs retrieved in different localities withint the Sesia Val Grande UNESCO Geopark: (a) Alpe Sassoledo; (b) Alpe Pianzà in the Vigezzo Valley; (c) Walser tytpical architecture in the Otro Valley.

According to the geographical concept of geotourism we also analysed further development of the use of stone resources in other SVUGG sectors, namely at Alagna (“Im Land” in the Walser German language) an alpine town of Upper Valsesia. This is the access point to the North face of Monte Rosa. It was settled by Walser colonist from Valais, Switzerland in the 14th century: since then it has preserved its alemanic language, culture and architecture (Figure 7c). The present day permanent resident population is about 600 inhabitants, while during winter season, over 5000 tourists per day are present at Alagna Valsesia. It has preserved its pristine character of typical alpine stone village.

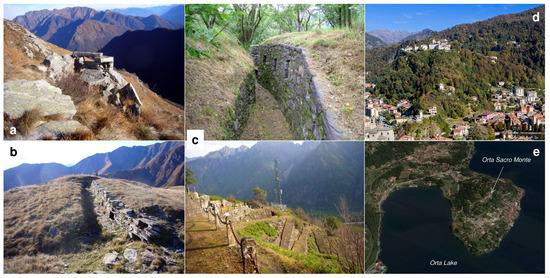

Figure 7.

Military defense and religious buildings withint the Sesia Val Grande UNESCO Geopark; (a,b) Strada Cadorna at Pian Vadà (a) and Monte Spalavera (b); (c) Strada Cadorna nearby the Stretta di Bara; (d,e) UNESCO Sacri Monti, located in peculiar geomorphological contexts: Varallo (d, photo courtesy of Carlo Pozzoni) and Orta (e, Google Earth 3D view).

Concerning the adaptation of defensive strategies to the morphology of the territory, the geomorphodiversity played an important role during human history. An important historical feature within the geopark is the presence of the Northern defensive border of the Italian territory towards North during the First World War, known as the Linea Cadorna (Figure 7a,b) In the Verbano area and in the lower Ossola Valley, this artificial path makes it possible to reach, relatively easily, high altitude spots in the SVUGG, and has locally become part of geotrails, as described in the results. In the specific case of the Toce Valley bottom, the line passes in correspondence of the narrower part (Stretta di Bara), where the Ossola Valley bottom reaches it lowest width value (about 700 m, (Figure 7c)).

Other examples of this relation are represented by the Special Reserves (UNESCO Heritage Sites) of the Sacri Monti. Among them, the Varallo (Figure 7d) and Domodossola Sacri Monti in particular are located on isolated hills along the Sesia and Toce rivers, respectively, while the Orta Sacro Monte occupy the top of a hill on a peninsula in the Orta Lake (Figure 7e).

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Geoheritage Analysis

In the framework of this research, a complete inventory of the on-site geoheritage (i.e., geosites and geotrails; in situ sensu Brilha [22]) and off-site geoheritage (museums, geo-laboratories; ex situ sensu Brilha [22]) has been performed, as potential resources for geotourism.

Concerning the on-site geoheritage, and geosites in the specific, the lists of the geosites included in the area of the SVUGG, retrieved from the geopark documentation, was examined and revised: they were related to both the application and the revalidation dossiers of the geopark. In the first phase of application (2013, http://www.sesiavalgrandegeopark.it/dossier-candidatura.html), during which the greater part of geosites were identified, they were assessed according to a matrix considering their scientific value, educational contents, and relevance as geotouristic destinations. In addition, their potentials for geoconservation, economic valorization, sustainable management, and conscious usage were carefully considered. This qualitative-quantitative method was applied according to the territory administrative boundaries, counting the presence of certain parameters (i.e., 0 or 1), and quantifying some of them (e.g., vulnerability from 1 to 4).

This initial list was then implemented considering the more recent adds related to the UNESCO Revalidation Dossier (2017). These new geosites derive from the most recent researches carried out on the SVUGG territory concerning mainly geosites meaning in terms of cultural geology and geomorphological landscape.

Hence, in the framework of this research, a shapefile containing all these inventoried geosites, with the respective location (WGS84 coordinates), the geometric properties (point, line, area) and a brief description, was created. The elevation of the geosites was extracted from the last Digital Terrain Model of the Piemonte Region (2009–2011; 5 m resolution). In order to provide a homogeneous classification, the geosites were assigned of:

- (i)

- A primary and a secondary scientific interest, according to the topics characterizing each one of them: GM = geomorphology; GRS = georesources; HYD = hydrogeology; M = mineralogy; P = petrography; PAL = paleontology; SD = sedimentology; SS = soil science; ST = structural. Moreover, the primary interest was classified according to its level of importance at the international, national, regional or local scale (sensu Panizza [104]).

- (ii)

- Additional interests: A = aesthetic; H = history/archaelogy; S = sport, e.g., [21,105].

All these considerations were made by widening the scope beyond the boundaries of the SVUGG, taking into consideration the scientific researches carried out at the international, national and regional levels, on these geosites and on other similar ones across the Alps.

Concerning geotrails, they were finally inventoried and grouped according to specific topics (GM = geomorphology; GRS = georesources; HYD = hydrogeology; M = mineralogy; P = petrography; PAL = paleontology; SD = sedimentology; SS = soil science; ST = structural). They were described according to type of installations (panels) and support materials (virtual, apps, paper guides). Moreover, they have been put in relation with geosites (related strictly to the geotrails or satellite) and with off-site geoheritage.

The off-site geoheritage has been also inventoried providing a brief description.

These 3 categories (geosites, geotrails and off-site geoheritage) were put in relation each other in specific tables (SF 1–3).

3.2. Methods for Implementing Geotrails

The second main goal of this work, which was to present solutions for enhanced geoheritage within the Sesia-Val Grande UNESCO Global Geopark, implies the popularization of geodiversity by “translating” the complexity of Earth system contents with simple languages [23], thus allowing a knowledgeable approach not only for people involved in the field of geosciences, but also for the general public and professionals involved in educational activities [27,106]. Currently, it is necessary to start cultural growth based on a process of communication and interpretation of our geological heritage, leading people to observe the processes affecting the physical world with greater awareness [28].

Hence, the trails proposed have been implemented with specific tools. Hence, among the listed geotrails, the most meaningful and representative ones mirroring the SVUGG geodiversity and offering a particular approach to landscape view were described in detail.

In the following subsections, the tools used at the selected geotrails, according to the specificity of each trail, are described.

3.2.1. MobileApp and Websites Tools for Enhancement of Virtual Tours within Geosites

In the last few years, the advancement of digital technologies and the large diffusion of Internet facilities have favored, in the field of cartography, but also for educational purposes [107], the increasing use of electronic devices and the development of dedicated software. In addition to the well-established appeal of videos available on the web [107], examples of these progresses are offered by webmap applications: GIS functionality is combined with Internet technology, allowing the publication of cartographical data integrated with other information, including hyperlinks to images and information [31,108]. These solutions can be valuable and comprehensive instruments to present results of Geosciences researches to the general public. In order to reach these goals and to promote the knowledge and the exploitation of the geosites in Piemonte region, a webmap application and mobile app (Figure 8) have been developed, through which it is possible to reach a large number of people. Moreover, this solution is economical and easy for users: whatever hardware or software configuration they are using for internet connection, and with only elementary computer knowledge, users can access the data shared by the webmap with a classic internet browser.

Figure 8.

Virtual tours inside the Sesia Val Grande UNESCO Global Geopark–Progeo Piemonte. Virtual App available in IOS and Google Play app stores.

The tools developed in the SVUGG context were largely based on the innovative approach introduced by the multidisciplinary project PROGEO-Piemonte, [23,40], further developed and tested within cooperative research and educational activities of the University of Torino and the SVUGG (H2020-COFUND “Tech4Culture” project). In order to select the most popular routes, popular products, educational initiatives, and public engagement events within the SVUGG were inventoried following the PROGEO-Piemonte standards, thus implementing both the related websites (http://www.progeopiemonte.it/en/aree/piemonte-nordorientale/; http://www.sesiavalgrandegeopark.it/). Each tour connects geosites and facilities (“stops”) providing descriptions of the natural and cultural landscape and interpretations of the related geological and geomorphological processes. The mobile app and webpage include nine different geotouristical tours located within the geothematic areas defined during the project: a tour network allowing people to begin their journey through the geoheritage of the Piemonte Region, considering both geological and cultural aspects. All the map tiles are integrated into the application, in order to avoid the need of downloading the map on the go, which in some cases might result with expensive roaming costs.

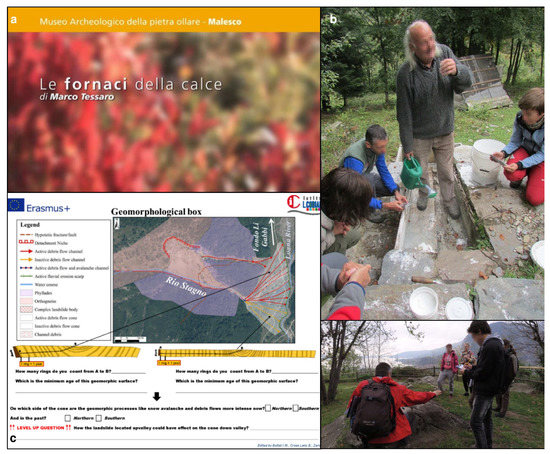

3.2.2. Multidisciplinary Educational Fieldworks for Understanding Spatio-Temporal Evolution of the Alpine Landscape

According to the principle of learning-by-doing [109], specific educational tools (learning aid sensu Orion [24]) were set for being expendable by students [27] and useful for teachers, who were often not familiar with Earth Sciences on the field and laboratory works [110]. The aim was to allow users to observe, measure and compare [24,111]. The geotrail along which these tools were implemented was, in particular, focused on the relation between geomorphological processes, climate change, vegetation response, and human settlements (i.e., Earth as a System [112]). Hence, simplified version of the geomorphological map (i.e., geomorphological boxes (Figure 9c) [21]) and simple exercises (Figure 9c), putting in relation geomorphology, dendrochronology, and dendrogeomorphology, were thought to make students work with methodologies of investigations applied by researchers for reconstructing the evolution of the Alpine physical landscape. These activities have been already tested in the framework, among others, of the Erasmus+ Project (see Section 2.2), are available on the panels along the trail, and are going to be freely downloadable from the website of the trail, together with dedicated web-based videos (Figure 9a).

Figure 9.

Fieldtrips activities inside the Sesia Val Grande UNESCO Global Geopark: (a) multimedia video available on the web on the lime kilns history in the Loana Valley for supporting field activities; (b) practical demonstration of the lime production in the Loana Valley; (c) simple exercises on the activity of geomorphological processes for students in the Loana Valley (modified from [27]); (d) fieldtrips with explanation to students of glacial modeling along the Sentiero Azzurro.

4. Results

The results of the inventory and implementation for geotrails are described here. Supplementary Files (SF 1–4) are available, including tables with the data and images of the on-site and off-site geoheritage.

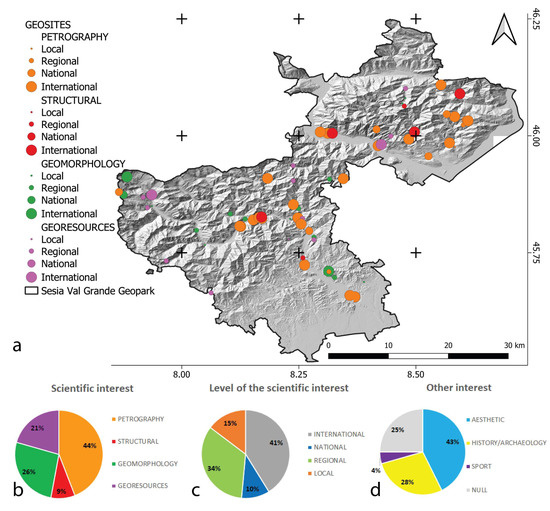

4.1. Geosite Inventory

Figure 10a shows the distribution of the geosites in the SVUGG and the complete information is included in SF 1. From a geographical point of view, they spread over the entire area of the geopark with a concentration along the existing geotrails. The elevation range of the geosites varies from about 200 m a.sl., in correspondence of the bottom of the Toce Valley, to more than 3200 m a.s.l. for the Monte Rosa massif.

Figure 10.

Distribution of the geosites in the Sesia Val Grande UNESCO Global Geopark (a), with the relative abundance of geosites according to the Scientific interest (b), level of Scientific interest (c), and other interest (d). Refer also to SF 1.

Considering their primary scientific value (Figure 10a,b), four main geological interests were identified: petrography (P), structural geology (ST), geomorphology (GM), and georesources (GRS). Some of the categories used in the inventory and applied to both geosites and geotrails were not associated with being of primary interest to any of the geosites (HYD = hydrogeology; M = mineralogy; PAL = paleontology; SD = sedimentology; SS = soil science). They are associated with some of the geosites as secondary interest. About half of the geosites (44%) are related to petrographic topics. Geomorphology, including glaciology, and georesources interests are quite equally represented (26% and 21% respectively), while the topic concerning structural geology can be identified in the 9% of the geosites as primary interest. Concerning the level of the scientific interest of the geosites (Figure 10a,c), the majority of them have an international importance (41%) and mainly correspond to the petrographic and structural categories. They are followed, in number, by the geosites with regional interest (34%). Geosites of national and local importance are less represented (10% and 15% respectively). Finally, regarding other interest (Figure 10d), many geosites are characterized by attributes related to their aesthetic value (43%). Some of them present an historical and/or archaeological interest (28%), and the minority are exploited for sport activities (4%). For 25% of the geosites, none of the mentioned additional interests can be identified.

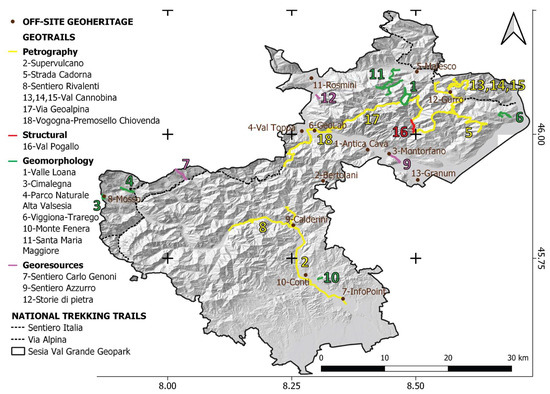

4.2. Geotrails Analysis

In the following paragraphs, a selection of seven geotrails, over a total of 18 within the geopark territory reported in Figure 11, is proposed, to show geodiversity of the SVUGG (Figure 12) and the different approaches adopted to involve users (Figure 8 and Figure 9), be they the general public (tourists, amateurs) or students in schools of different orders.

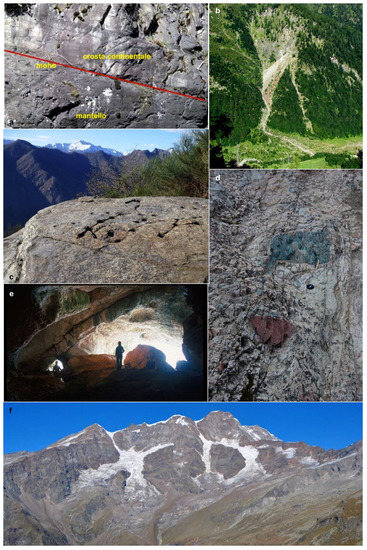

Figure 12.

Geodiversity along the geotrails in the Sesia Val Grande UNESCO Global Geopark: (a) Moho surface in outcrop at Premosello Chiovenda (51, SF 1; 18, SF 2); (b) Pizzo Stagno landslide (18, SF 1; 1, SF 2); (c) Alpe Prà petroglyphs in the Val Grande National Park; (d) Caldera megabreccia at Prato Sesia (50, SF 1; 2, SF 2); (e) Ciota Ciara cave in the Monte Fenera karst complex (22, SF 1; 10, SF 2); (f) panoramic view on the Monte Rosa from the Sesia Valley (31, SF 1; 4, SF 2). For other views on geodiversity along geotrails of the SVUGG, refer also to the SF 4.

The selection (grey in SF 2) is presented, starting from the petrographic topic (4.2.1; 4.2.2; yellow in Figure 11), through geomorphology and glaciology topics (4.2.3; 4.2.4; 4.2.5; 4.2.6; green in Figure 11), and concluding with a geotrail specifically focused on georesources (4.2.7; violet in Figure 11). The data of each geotrail are reported in SF 2, and more images are available in SF 4. In SF 2 and in Figure 11, the Via Geoalpina is inserted (17, SF 2): it is a complex, regional relevant trail that includes parts of other geotrails described and/or reported in SF 2 (1, 5, 16, 18; h, i, l, SF 4-II). Hence, portions of this regional trail are equipped, but the whole Via Geoalpina is herein marked. Moreover, the Via Alpina and the Sentiero Italia are included in the map too, since they represent non-thematic trails of national relevance. Variations of trails conditions are communicated to visitors near real-time, as, for example, in the case of interruption of trails due to hydrogeological instability processes, such as the one very recently occurred along the Pogallo Valley trail (16 in Figure 11) during May 2020.

4.2.1. “Viaggio Spazio-Temporale Nelle Profondità Della Terra” (A Space-Time Journey Inside the Earth depths; 18, SF 2)

This trail was inaugurated in April 2013. It runs along the mountain slope behind the Vogogna and Premosello-Chiovenda villages and is relatively simple, but with some exposed stretches. It is equipped with 10 thematic panels located on significant outcrops, available on the web, plus one introductory panel at the beginning of the itinerary. It is focused on three main geologic themes, which may stimulate the curiosity of the general public:

- i.

- The boundary between the Central and the Southern Alps (c, SF 4-II) is along the Insubric Line. The attention is focused on the juxtaposition between the Central Alps, consisting of refolded basement nappes affected by the Alpine metamorphism, and the Southern Alps, which are little affected by that phase and preserving much older structures. The visitors may observe the phyllonites (8, SF 1; b, SF 4-II), produced by the deformation of Austroalpine rocks along the fault zone, and their contact with the mafic granulites of the Ivrea-Verbano Zone (Southern Alps).

- ii.

- A journey from the upper to the lower crust: Along the path, the visitor ideally walks deeper and deeper inside the crust, reaching rocks formed at a depth of over 30 km.

- iii.

The itinerary also allows observations on the geomorphology of the area (glacial, gravity- and water-related landforms). The trail is illustrated in detail in the Geolab “Luigi Burlini” (6, SF 2; e, f, SF 4-II), located in the Vogogna village, near the beginning of the itinerary and in a web-based video (SF 2; g, SF 4-II). Unfortunately, a section of the trail is currently closed for a landslide and the path indicated in Figure 11 and in SF 2 is the part allowed at this moment.

4.2.2. “Il Supervulcano della Valsesia” (The Sesia Supervolcano; 2, SF 2)

The Sesia Supervolcano geotrail was realized within the network of PROGEO-Piemonte geothematic virtual tours and published as a book and online by PROGEO mobile app and Progeo online webmap. The free mobile application (iOS and Google Play versions) and the free webmap page (www.progeopiemonte.it/path/valsesia.html) were published to enhance and promote geological heritage in the Piemonte Region, and specifically in the Sesia Valley. The itinerary proposed consists of 10 stops reachable by car or by short walking trails, and it is supported by the Supervolcano Infopoint in Prato Sesia (7, SF 3). The Valsesia itinerary permits observations on what was going on around 280 Ma ago, in and below an active supervolcano, which extended for at least 25 km deep in the Earth’s crust. Today this area is an open-air laboratory: by observing different evidences (1, 4, 6, 16, 20, 23, 24, 25, 26, 33, 41, 47, 50, 58, SF 1), geologists can study the processes that lead an active supervolcano to collapse in a caldera (Figure 12d), after a major eruption (SF 4-IV). The wealth of scientific data and interpretations presented through the stops of the itinerary allows also not expert visitors to reconstruct accurately the history of magmatic processes of the Sesia Supervolcano. Approximately 295 Ma ago, partial melting of the mantle produced magmas that were introduced into the deeper part of the crust, forming the so-called Mafic Complex. About 288 Ma ago, heat from this deep magmatic body melted the upper crust, forming granitic bodies known as the Graniti dei laghi. In both lower and upper crust, hybrid magmas formed as well, due to mixing of magmas of different origin. In the same period, the magmatic activity reached the Earth’s surface. Later, about 280 Ma ago, a super-eruption collapsed the volcanic system, forming a caldera with a diameter of at least 13 km: it is estimated that more than 500 km3 of magma were erupted. It is one of the most violent known magmatic events, which evidences are still preserved along Sesia Valley despite the successive geological events. Then, 90 Ma ago, the Earth’s crust slowly opened, creating the Tethys Ocean. Only in the last 30 Ma, during the formation of the Alps, the collision between Africa and Europe exposed a slice of the African crust containing the whole magmatic system of the supervolcano (c, SF 4-IV).

4.2.3. L’ Anello Geoturistico della Valle Loana (The Loana Valley Geotouristic Ring; 1, SF 2)

In 2019, a geotouristic trail was equipped along the Loana Valley in the Malesco Municipality, thanks to GAL funding from Fondo Europeo Agricolo per lo Sviluppo Rurale (FEAR). The trail is articulated in two parts: (i) the first one runs along the valley bottom; it is a touristic, easily accessible; (ii) the second one reaches the head of the valley as far as the northern border of the Val Grande National Park. Both the proposals were set starting from the existing excursionist trail network and they have both a ring pattern. Six geostops were identified along the trails and equipped with panels (e, SF 4-I,) containing essential information, and most of them are enriched with simplified mapping tools [21]. The trail is focused on the evolution of the Alpine landscape under glacial, snow-, water- and gravity-related processes, in relation to vegetation and human settlements. Considering these topics, the trail is recommended only in safe conditions. The trail is inserted in the offer of the “Ecomuseo ed leuzerie e di scherpelit - Museo del Parco Nazionale della Val Grande” of the Malesco Municipality (5, SF 3), from which, in 2020 a pdf-format guide to the trail will be made also available, together with virtual videos (f, SF 4-I), in the specific session of the thematic trails. The trail is focused on three main topics:

- i.

- Lithological and structural control on geomorphological modelling—the Loana Valley is a S-N oriented valley that was carved by glaciers during the Pleistocene. The head of the valley is characterized by a glacio-structural saddle due to the presence of the Canavese Line (a, SF 4-I). The area represents a noteworthy place for the study of deformations related to the CL (i.e., Scaredi Formation; [41]), as testified by several authors [44,50,51,52]. The influence of the deformation pattern on the surficial modelling is particularly evident where different lithotypes, including marbles (27, SF 1), which crop out in structural contact, producing different relief features.

- ii.

- Ecologic support role on landforms—the geomorphic processes interesting currently and during the past the Loana valley deeply affect the vegetation distribution in the area. Bollati et al. [99,113] detected specific patterns of disturbance on vegetation growing on the geosites located along the valley bottom (18, SF 1; b, c, SF 4-I), and on vegetation growing on carbonate isolated reliefs modelled by glaciers in the past, near the head of the valley (17, SF 1; Figure 12b). These results were proposed in form of simple exercises, addressed to general public and schools, allowing them to relate the vegetation behavior with the geomorphological activity (Figure 9c).

- iii.

- Cultural value of georesources—in addition to the most famous "Pietra ollare” (x, SF 1), along this trail, the attention is focused on carbonate outcrops located in the valley and quarried in the past to produce lime (Figure 9a). Old lime kilns, located in the valley bottom, have been recently restored with the possibility, for tourists and schools, of experimenting lime production (Figure 9b; d, SF 4-I). The carbonate outcrops (17, SF 1) represent georesources, a particularly relevant consideration in a geopark where the link with local populations and resources usages is extremely important.

4.2.4. L’Itinerario Glaciologico del Parco Naturale Alta Valsesia (Upper Sesia Valley Natural Park Glaciological trail, 4, SF 2)

At the beginning of the 1990s, a glaciological trail was equipped in the Upper Sesia Valley Natural Park in the Alagna Valsesia Municipality. Starting from the existing network of local hiking tracks, the trail was set up as a round-trip route. Eight geostops were identified along the trail, each one equipped with display panels. The southeastern side of Monte Rosa belonging to Sesia Valley is the less glacierized among the five sides of the massif. There are no active valley glaciers similar to Gorner (northwestern side), Verra and Lys glaciers (southwestern side), neither large debris-covered glaciers like Belvedere Glacier (northeastern). Nevertheless, thanks to the glaciological trail of the Upper Sesia Valley Natural Park, it is possible to observe magnificent glacial landscapes of high environmental and scientific interest. The aim of the trail is to guide hikers in the observation and recognition of the most evident and significant landforms shaped by glaciers, during their expansion and recessional phases. For this purpose, the first geostop describes past climatic fluctuations: particularly those dating back to the last million year related to Pleistocene glaciations. The seven geostops illustrate three main topics:

- i.

- The process of glacial erosion and related landforms, from the micro to the macro scale—at the beginning of the trail, it is possible to observe the “Caldaie del Sesia” landform system (e, SF 4-V) modelled by subglacial water of the ancient Sesia Glacier. The system is composed by a gorge where the Sesia River is channeled through a rock step, producing a high waterfall, and a huge kettle. Another example is a roche moutonnée with potholes, good example of landforms related to abrasion and/or plucking processes. Finally, some geostops illustrate large scale erosion processes, particularly those related to the Bors Valley hanging valley and glacial cirque.

- ii.

- The processes and landforms related to glacial accumulation—hikers walk along the ridge of a glacial deposit, the “Fondecco moraine” (d, SF 4-V). This shows the dimensions reached by the ancient Sesia Glacier during the late glacial advances, during the end of Pleistocene.

- iii.

- Glaciers and their dynamics—glaciers of the Sesia Valley side of the Monte Rosa (31, SF 1; Figure 12f; g, h, SF 4-V) are described with information on their past areal dimensions. The trail ends in proximity of the current glacier snout, where it is possible to observe crevasses and seracs; moreover, it is also possible to observe moraines and roche mountonnée (f, SF 4-V) shaped by glaciers during the Little Ice Age.

Thanks to the information acquired from the display panels during the ascending route, the hikers are invited, during the descent, to identify and recognize glacial landforms by themselves. The glaciological trail of the Upper Sesia Valley Natural Park has been recently included among the glaciological itineraries on the Italian glacial mountains [90,91]. The contents of the trail drive the attention of the geotourists to some of the most important topics of the present-day debate on environmental changes of the glacial environments [114].

4.2.5. Geological-Pedological Trail of the Cimalegna Plateau (Itinerario geologico-pedologico dell’altopiano di Cimalegna; 3, SF 2)

The Cimalegna glaciological-pedological trail is located in the high-altitude plateau (2800–3000 m a.s.l.) at the Western border of the geopark (Alagna Valsesia municipality). For its structural geology context, the Cimalegna plateau (3, SF 1) is an ideal place to examine the geological history of the North-Western Alps, with particular regard to the geological dynamics of the last 200 Ma [115]. Moreover, here, glacial and periglacial features and soils, show a high variety, and the typical pedogenetic processes of this high-altitude cold environment are well expressed. The Cimalegna plateau is also a relevant location for scientific studies promoted by University of Torino. The “Angelo Mosso Scientific Institute” (8, SF 3; a, SF 4-V) was established here on 1907 for physiological studies at high altitude [116], then upgraded by the Geophysical Observatory conducted by Umberto Monterin since 1927 [117] and, later, by the Snow and Alpine Soils Laboratory. Here, the NatRisk research Team (www.natrisk.unito.it) established a base for studies on glacial and periglacial environments [118,119]), and contributed to the recognition of the Cimalegna site as the Alpine site of the Italian Network for Long-Term Ecological Research (www.lteritalia.it), part of the LTER International Network (ILTER; www.ilternet.edu/). The Cimalegna trail was established by the Ente di Gestione delle Aree Protette della Valle Sesia in 2008 [120], to offer public engagement activities for high school students, naturalistic and environmental associations, such as training courses relating to hiking and mountaineering (c, SF 4-V). The circular route of the Cimalegna path starts from the Passo dei Salati, descends to the “Angelo Mosso Scientific Institute”, near Bodwitch Lake, continues east to the Col d’Olen (2881 m), climbs up the Corno del Camoscio horn (3024 m a.s.l.) for a 360° viewpoint on the southern slope of the Monte Rosa, then it descends back to the Passo dei Salati. Along the trail, eight display panels were placed, illustrating the geological history of this area with photographs and diagrams, starting from an ancient ocean, the Tethys, up to the formation of the Alps, also dwelling on the soils (b, SF 4-V), which are formed here in particular conditions, due to the presence of an almost flat area, of high-altitudes, and extreme climatic conditions. Further engaged research activities are possible at the “Angelo Mosso Scientific Institute”, with audiovisuals projections on specific topics [36], and the exhibition of pedoliths of the soils of Cimalegna (reconstruction in the laboratory of an entire soil profile, made using the material taken in the field; [121]) and a collection of lithotypes from the area [120].

4.2.6. Monte Fenera Caves Trail (Sentiero delle Grotte del Monte Fenera; 10, SF 2)

The peculiarity of Monte Fenera is the presence of many caves (22, SF 1; f, g, SF 4-III) which, over the course of thousands of years, have been occupied by living beings of various animal species, including some extinct ones, such as Ursus Spelaeus, Merk’s rhinoceros, and even by Homo neanderthalensis, whose finds retrieved at Fenera give the mountain the primacy of the oldest prehistoric site in Piemonte [102,122]. An articulated karst system has developed inside the carbonate rocks (limestone and dolomites) of the Monte Fenera. The preservation of these kinds of rocks in Valsesia is the consequence of the tectonics of the area: in particular, of those faults, the most important is the Cremosina Line, that, causing the movement of large rocky masses, allowed the preservation of Mesozoic rocks from erosion as happened in the neighboring portions. The geotrail was set up with 12 explanatory display boards. The first seven panels focus on geology, describing the rocks that constitute the Monte Fenera (from the oldest dating back to 280 Ma ago, to the more recent ones that emerge from the slopes of the mountain relief), and on the structural assets of the area, characterized by important tectonic lines. Two panels are dedicated to the description of the karst system with concretions. The most important caves (22, SF 1) are: “Grotta delle Arnarie” (3500 m of development), “Buco della Bondaccia” (500 m of development), “Ciota Ciara” (200 m; Figure 12e) and “Il Ciutarùn” (about 70 m). At the entrances of the last three caves, a descriptive panel of each individual underground cavity was placed: the development, the speleological and biological aspects, with images of the interior of the caves and of the species adapted to the underground life that live in them or find a temporary shelter. A panel relating to the archaeological excavations made by the University of Ferrara was also placed at the “Ciota Ciara”.

4.2.7. Sentiero Azzurro (The Azzurro Trail; 9, SF 2)

The Mont’Orfano (Figure 3e and Figure 5b) is an isolated peak at the end of Ossola Valley, facing both the Mergozzo and Maggiore lakes. Its lithological composition, mainly of white and green granite, together with the presence of local faults, made it to survive to erosion by the Toce Glacier during the Ice Ages, and thus, standing alone, separated from the Mottarone massif, the Massone massif, and the mountains belonging to Val Grande National Park. Due to the presence of granite, it had (and still has, even if reduced) significant importance as a georesource for local communities. On its slopes, for many centuries, about thirty quarries operated to extract big and small rock blocks, mainly used in local buildings, but in the 19th and 20th centuries, lots of sculptures and monuments were made all over the world with the Montorfano white granite. The trail, belonging to the cultural offer of Ecomuseo del Granito (3, SF 3), develops on an easy and historical path, starting from the main village of Mergozzo to reach the small village of Montorfano, just in the middle of the largest quarries, of which only one is still active. Along the path, some panels explain, with the aid of historical pictures, the techniques used in extracting, moving and working the granite blocks (a, b, SF 4-III). Thus, the trail has not only a geological importance, but even an anthropological one, because the quarries have been the only economic resource for decades for the local communities of Mergozzo and the surrounding area. The trail ends at Belvedere, a scenic point of view on Mergozzo and Maggiore lakes (x, SF 1), with an explanatory panel about lake geomorphology and the formation of the first one, in relation to sediment transport rates that have characterized the Toce River (Figure 3e and Figure 9d).

4.3. The Off-Site Geoheritage within the Sesia-Val Grande UNESCO Global Geopark (Museum, Geo-Laboratories)

In the wide area of the SVUGG there are 13 science museums and Park visitor centers closely linked to the activities and themes of the geopark (SF 3, SF 4). Some of them are directly managed by the Regional Natural Park or the National Natural Park and others are managed by four official ecomuseums (recognized by Piemonte regional law), together with local Municipalities. The Ecomuseum is a tool for the participatory management of the natural and cultural heritage of a territory [123], thus it does not focus only on the scientific aspect and the static element (i.e., a rock collection), but enhances that element in the context of the territory and its community. Moreover, it is not an open-air museum nor a diffuse museum, but it is a cultural container. Only few museums are privately owned, but are usually open to the public during tourist season or on reservation.

This off-site geoheritage represents a very important element for the Earth Sciences knowledge of the area, because each of these entities focuses its attention on a specific topic, sometimes with substantial collections that also have a historical value (i.e., Museo di Scienze Naturali “Mellerio Rosmini”, 11, SF 3, and Museo “Pietro Calderini” 9, SF 3). The off-site geoheritage is only not represented by collections of rocks and minerals, but also by specific explanatory sections, inside museums and visitor centers, about the georesources and their use in past and present times. In some cases, there is a strong connection between the archaeological heritage and the geological one (i.e., Ecomuseo ed leuzerie e di scherpelit - Museo del Parco Nazionale della Val Grande, 5, SF 3; f, SF 4-I; Museo Archeologico e Paleontologico “Carlo Conti”, 10, SF 3). Many of them are also connected with the on-site geoheritage, are near-by geosites or geotrails, and offer lots of information for the outdoor visits. In two cases, Ecomuseo della Val Toppa (4, SF 3) and Antica Cava (1, SF 3) are actually on-site geoheritage elements (an old gold mine and an old marble quarry), but they are managed as museums, with opening times and guided visits. Some structures offer educational services both for students of all ages and for adults, with the aid of well and specific trained educators and guides. These kinds of activities can join both laboratories and excursions, not only for working on general themes, but also to make the territory and its peculiarities known especially by students in schools. In particular, the Geolab “Luigi Burlini” in Vogogna (6, SF 3; e, f, SF 4-II), was thought as an area for the study and the teaching of themes related to Earth Sciences. It is equipped with a stereo microscope and a polarized light microscope, featuring high-definition video cameras and video devices, and also provides a collection of thin sections of the main rocks in the area, a mineralogical and lithological collection, and interactive instruments with pictures and animations of the main themes related to the geology of the area of the Val Grande National Park.

5. Discussions and Conclusions