Cost–Utility Analysis of PCSK9 Inhibitors and Quality of Life: A Two-Year Multicenter Non-Randomized Study

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Patient Disposition

2.2. Baseline Characteristics and Concomitant Medication

3. Outcomes

3.1. Primary Endpoint: Cost–Utility

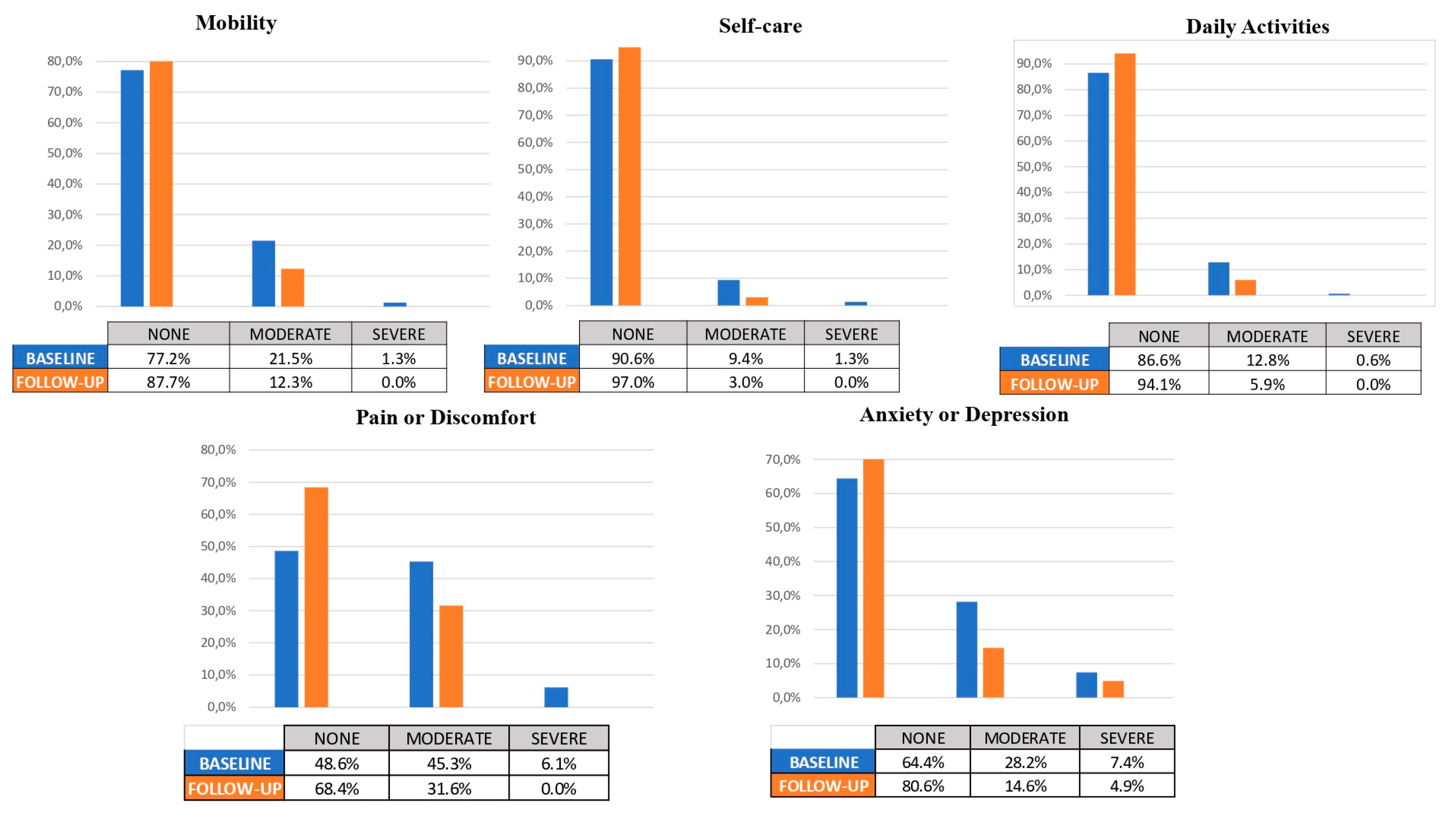

3.2. Secondary Endpoint: Changes in QoL

4. Discussion

5. Limitations

6. Material and Methods

6.1. Study Design

6.2. Population

6.3. Study Procedures

6.4. End Points

6.5. Cost–Utility Analysis

6.6. Statistical Analysis

7. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- GBD 2017 Causes of Death Collaborators. Global, regional, and national age-sex-specific mortality for 282 causes of death in 195 countries and territories, 1980–2017: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet 2018, 392, 1736–1788, Erratum in: Lancet 2019, 393, e44; Erratum in Lancet 2018, 392, 2170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Grundy, S.M.; Stone, N.J.; Bailey, A.L.; Beam, C.; Birtcher, K.K.; Blumenthal, R.S.; Braun, L.T.; de Ferranti, S.; Faiella-Tommasino, J.; Forman, D.E.; et al. 2018 AHA/ACC/AACVPR/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/ADA/AGS/APhA/ASPC/NLA/PCNA Guideline on the Management of Blood Cholesterol: Executive Summary: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2019, 73, 3168–3209, Erratum in J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2019, 73, 3234–3237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sabatine, M.S.; Giugliano, R.P.; Keech, A.C.; Honarpour, N.; Wiviott, S.D.; Murphy, S.A.; Kuder, J.F.; Wang, H.; Liu, T.; Wasserman, S.M.; et al. Evolocumab and Clinical Outcomes in Patients with Cardiovascular Disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 376, 1713–1722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwartz, G.G.; Steg, P.G.; Szarek, M.; Bhatt, D.L.; Bittner, V.A.; Diaz, R.; Edelberg, J.M.; Goodman, S.G.; Hanotin, C.; Harrington, R.A.; et al. Alirocumab and Cardiovascular Outcomes after Acute Coronary Syndrome. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 379, 2097–2107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garrison, L.P., Jr.; Neumann, P.J.; Erickson, P.; Marshall, D.; Mullins, C.D. Using real-world data for coverage and payment decisions: The ISPOR Real-World Data Task Force report. Value Health 2007, 10, 326–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luengo-Fernandez, R.; Walli-Attaei, M.; Gray, A.; Torbica, A.; Maggioni, A.P.; Huculeci, R.; Bairami, F.; Aboyans, V.; Timmis, A.D.; Vardas, P.; et al. Economic burden of cardiovascular diseases in the European Union: A population-based cost study. Eur. Heart J. 2023, 44, 4752–4767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olry de Labry Lima, A.; Gimeno Ballester, V.; Sierra Sánchez, J.F.; Matas Hoces, A.; González-Outón, J.; Alegre Del Rey, E.J. Cost-effectiveness and Budget Impact of Treatment with Evolocumab Versus Statins and Ezetimibe for Hypercholesterolemia in Spain. Rev. Esp. Cardiol. Engl. Ed. 2018, 71, 1027–1035, Erratum in Rev. Esp. Cardiol. 2018, 71, 1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagepally, B.S.; Sasidharan, A. Incremental net benefit of lipid-lowering therapy with PCSK9 inhibitors: A systematic review and meta-analysis of cost-utility studies. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2022, 78, 351–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janssen, M.F.; Szende, A.; Cabases, J.; Ramos-Goñi, J.M.; Vilagut, G.; König, H.H. Population norms for the EQ-5D-3L: A cross-country analysis of population surveys for 20 countries. Eur. J. Health Econ. 2019, 20, 205–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scicchitano, P.; Milo, M.; Mallamaci, R.; De Palo, M.; Caldarola, P.; Massari, F.; Gabrielli, D.; Colivicchi, F.; Ciccone, M.M. Inclisiran in lipid management: A Literature overview and future perspectives. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2021, 143, 112227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhatt, D.L.; Briggs, A.H.; Reed, S.D.; Annemans, L.; Szarek, M.; Bittner, V.A.; Diaz, R.; Goodman, S.G.; Harrington, R.A.; Higuchi, K.; et al. Cost-Effectiveness of Alirocumab in Patients With Acute Coronary Syndromes: The ODYSSEY OUTCOMES Trial. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2020, 75, 2297–2308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laupacis, A.; Feeny, D.; Detsky, A.S.; Tugwell, P.X. How attractive does a new technology have to be to warrant adoption and utilization? Tentative guidelines for using clinical and economic evaluations. CMAJ 1992, 146, 473–481. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Plans-Rubió, P. Cost-effectiveness of cardiovascular prevention programs in Spain. Int. J. Technol. Assess. Health Care 1998, 14, 320–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Cock, E.; Miravitlles, M.; González-Juanatey, J.R.; Azanza-Perea, J.R. Threshold value of cost per life-year gained to recommend the adoption of healthcare technologies in Spain: Evidence from a literature review. Pharmacoeconomics Span. Res. Artic. 2007, 4, 97–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leech, A.A.; Kim, D.D.; Cohen, J.T.; Neumann, P.J. Use and Misuse of Cost-Effectiveness Analysis Thresholds in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: Trends in Cost-per-DALY Studies. Value Health 2018, 21, 759–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Azari, S.; Rezapour, A.; Omidi, N.; Alipour, V.; Behzadifar, M.; Safari, H.; Tajdini, M.; Bragazzi, N.L. Cost-effectiveness analysis of PCSK9 inhibitors in cardiovascular diseases: A systematic review. Heart Fail. Rev. 2020, 25, 1077–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Villa, G.; Lothgren, M.; Kutikova, L.; Lindgren, P.; Gandra, S.R.; Fonarow, G.C.; Sorio, F.; Masana, L.; Bayes-Genis, A.; Hout, B.V. Cost-effectiveness of Evolocumab in Patients With High Cardiovascular Risk in Spain. Clin. Ther. 2017, 39, 771–786.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fonarow, G.C.; van Hout, B.; Villa, G.; Arellano, J.; Lindgren, P. Updated Cost-effectiveness Analysis of Evolocumab in Patients With Very High-risk Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease. JAMA Cardiol. 2019, 4, 691–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Grégoire, J.; Champsi, S.; Jobin, M.; Martinez, L.; Urbich, M.; Rogoza, R.M. Cost-Effectiveness Analysis of Evolocumab in Adult Patients with Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease in Canada. Adv. Ther. 2022, 39, 3262–3279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Seijas-Amigo, J.; Rodríguez-Penas, D.; Estany-Gestal, A.; Suárez-Artime, P.; Santamaría-Cadavid, M.; González-Juanatey, J.R. Observational multicentre prospective study to assess changes in cognitive function in patients treated with PCSK9i. Study protocol. Farm. Hosp. 2021, 45, 150–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- EuroQol Group. EuroQol--a new facility for the measurement of health-related quality of life. Health Policy 1990, 16, 199–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ministry of Health. Average Costs of Diagnosis-Related Groups (DRG). Available online: https://www.sanidad.gob.es/estadEstudios/estadisticas/inforRecopilaciones/anaDesarrolloGDR.htm (accessed on 27 August 2024).

- Florio, M. Applied Welfare Economics: Cost-Benefit Analysis of Projects and Policies; Routledge: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Instituto Galego de Estadística [Internet]. [Place Unknown]: Instituto Galego de Estadística. Available online: https://www.ige.gal/web/mostrar_actividade_estatistica.jsp?idioma=es&codigo=0204031014 (accessed on 27 August 2024).

- Robusté, F.; Campos Cacheda, J.M. Els Comptes del Transport de Viatgers a la Regió Metropolitana de Barcelona; Autoritat del Transport Metropolità: Barcelona, Italy, 2000; ISBN 84-7653-744-1. [Google Scholar]

- CIS-IMSERSO Encuesta Sobre Personas Mayores. 2010. Available online: https://www.imserso.es/imserso_01/espaciomayores/esprec/enc_ppmm/index.htm (accessed on 27 August 2024).

- Centro de Investigaciones Sociológicas. Estudio “Condiciones de Vida de las Personas Mayores”. Available online: http://www.cis.es/cis/opencm/ES/1_encuestas/estudios/ver.jsp?estudio=7740&cuestionario=8954&muestra=14085 (accessed on 27 August 2024).

| Demographic, Baseline Characteristics and Treatments | |

|---|---|

| Sex (male); n (%) | 105 (66.50) |

| Years; mean (SD) | 60.6 (10.20) |

| Height; mean (SD) | 1.67 (0.08) |

| Weight; mean (SD) | 81.0 (15.70) |

| Medical history; n (%) | |

| Cardiovascular disease | 134 (84.80) |

| Familiar hypercholesterolemia | 39 (24.70) |

| Statins intolerance | 69 (43.70) |

| Dementia history | 31 (19.60) |

| Diabetes | 35 (22.20) |

| Hypertension | 87 (55.10) |

| Heart failure | 27 (17.10) |

| Diet | 114 (72.20) |

| Smoking status; n (%) | |

| Current | 17 (10.80) |

| Past smoker | 85 (53.80) |

| Never | 56 (35.40) |

| PCSK9 inhibitors; n (%) | |

| Alirocumab 150 mg | 65 (41.10) |

| Alirocumab 300 mg | 18 (11.40) |

| Evolocumab 240 mg | 75 (47.50) |

| Statins; (%) | |

| Rosuvastatin | 33.50 |

| Atorvastatin | 18.40 |

| Pitavastatin | 3.20 |

| Other statins | 1.20 |

| Ezetimibe | 58.60 |

| LDL-c; mg/dL (SD) | |

| Baseline | 145.18 (43,43) |

| Follow-up | 62.11 (57.00) |

| IAM_No. | Angina Inestable_No. | Stroke_No. | PCI_No. | CABG_No. | Death_cv | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PCSK9i | 3 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 |

| Standard | 4 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 0 |

| Death due to other causes were not included into analysis in both arms (2 deaths due to cancer). | ||||||

| DRG | COST (EUR ) | |||||

| Myocardial Infarction | 5183.35 | |||||

| Unstable Angina | 4594.27 | |||||

| Stroke | 3748.38 | |||||

| Percutaneous Coronary Intervention | 10843.58 | |||||

| Cardiac Surgery (Bypass) | 29500.06 | |||||

| Ministry of Health. Average costs of Diagnosis-Related Groups (DRG). Available at: https://www.sanidad.gob.es/estadEstudios/estadisticas/inforRecopilaciones/anaDesarrolloGDR.htm (accessed on 7 August 2024). | ||||||

| Results | Amount (EUR ) |

|---|---|

| Pharmacological treatment cost PCSK9 inhibitors | EUR 13,633.39 |

| Pharmacological treatment cost standard therapy | EUR 3638.25 |

| Total event cost PCSK9 inhibitors | EUR 35,582.17 |

| Unit event cost PCSK9 inhibitors | EUR 223.78 |

| Total event cost standard therapy | EUR 118,951.87 |

| Unit event cost standard therapy | EUR 748.12 |

| Total premature death cost PCSK9 inhibitors | EUR 80,843.68147 |

| Total premature death cost standard therapy | EUR 0 |

| Unit cost of events + mortality PCSK9 inhibitors | EUR 732.23 |

| Unit cost of events + mortality standard therapy | EUR 748.12 |

| Discount rate: 3.5% | |

| Total unit cost for pharmacological treatment PCSK9 inhibitors after discount rate | EUR 13,410.46 |

| Total unit cost for pharmacological treatment standard therapy after discount rate | EUR 4094.72 |

| QoL PCSK9 inhibitors (2 years) | 1.648851948 |

| QoL PCSK9 inhibitors (2 years) after discount rate | 1.53922094 |

| QoL standard therapy (2 years) | 1.454807792 |

| QoL standard therapy (2 years) after discount rate | 1.35807864 |

| ICER: (Total unit cost PCSK9 inhibitors—Total unit cost standard therapy)/(QoL PCSK9 inhibitors—QoL standard therapy) | EUR 51,427.72 |

| MOBILITY | SELF-CARE | DAILY ACTIVITIES | PAIN/ DISCOMFORT | ANXIETY/ DEPRESSION | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | FU | Baseline | FU | Baseline | FU | Baseline | FU | Baseline | FU | |

| None | 77.20 | 87.70 | 90.60 | 970 | 86.60 | 94.10 | 48.60 | 68.40 | 64.40 | 80.60 |

| Moderate | 21.50 | 12.30 | 9.40 | 3.00 | 12.80 | 5.90 | 45.30 | 31.60 | 28.20 | 14.60 |

| Severe | 1.30 | 0.00 | 1.30 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 6.10 | 0.00 | 7.40 | 4.90 |

| p-value | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |||||

| EVA | Baseline | 67.04( ± 20.069) | 66.62–72.67 | 0.086 | ||||||

| End point | 69.64( ± 18.683) | 63.81–70.27 | ||||||||

| MOBILITY | SELF-CARE | DAILY ACTIVITIES | PAIN/ DISCOMFORT | ANXIETY/ DEPRESSION | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Females | Males | Females | Males | Females | Males | Females | Males | Females | Males | |

| None | 84 | 89 | 94 | 97 | 86 | 92 | 73 | 23 | 90 | 95 |

| Problems | 16 | 11 | 6 | 3 | 14 | 8 | 27 | 17 | 10 | 5 |

| EVA | Females | 71 | ||||||||

| Males | 73 | |||||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Seijas-Amigo, J.; Mauriz-Montero, M.J.; Suarez-Artime, P.; Gayoso-Rey, M.; Reyes-Santías, F.; Estany-Gestal, A.; Casas-Martínez, A.; González-Freire, L.; Rodriguez-Vazquez, A.; Pérez-Rodriguez, N.; et al. Cost–Utility Analysis of PCSK9 Inhibitors and Quality of Life: A Two-Year Multicenter Non-Randomized Study. Diseases 2024, 12, 244. https://doi.org/10.3390/diseases12100244

Seijas-Amigo J, Mauriz-Montero MJ, Suarez-Artime P, Gayoso-Rey M, Reyes-Santías F, Estany-Gestal A, Casas-Martínez A, González-Freire L, Rodriguez-Vazquez A, Pérez-Rodriguez N, et al. Cost–Utility Analysis of PCSK9 Inhibitors and Quality of Life: A Two-Year Multicenter Non-Randomized Study. Diseases. 2024; 12(10):244. https://doi.org/10.3390/diseases12100244

Chicago/Turabian StyleSeijas-Amigo, José, Maria José Mauriz-Montero, Pedro Suarez-Artime, Mónica Gayoso-Rey, Francisco Reyes-Santías, Ana Estany-Gestal, Antonia Casas-Martínez, Lara González-Freire, Ana Rodriguez-Vazquez, Natalia Pérez-Rodriguez, and et al. 2024. "Cost–Utility Analysis of PCSK9 Inhibitors and Quality of Life: A Two-Year Multicenter Non-Randomized Study" Diseases 12, no. 10: 244. https://doi.org/10.3390/diseases12100244