Joseph Beuys’ Rediscovery of Man–Nature Relationship: A Pioneering Experience of Open Social Innovation

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Methodology

3. Beuys’ Approach to Change: From Individual Artwork to Collective Transition

“My understanding of art is strictly related to everybody’s work. […]. So organically it is related to the working places of the people. And the element of self-doing, the element of self-determination, self-administration and self-organisation is the element of this anthropological type of art”.[24]

“This threefold human being underpins Beuys’ unflagging commitment to the need for direct democracy, to an associative economics, and to a free educational and cultural sphere that would enable people to realize their higher abilities”.[27]

“Art is the only possibility for evolution, the only possibility to change the situation in the world. But then you have to enlarge the idea of art to include the whole creativity. And if you do that, it follows logically that every living being is an artist—an artist in the sense that he can develop his own capacity. And therefore it’s necessary at first that society cares about the educational system, that equality of opportunity for self-realization is guaranteed”.[23]

“pooled and compared their practical experience […] to cover a range of pressing themes in which radical and creative new thinking is urgently needed, discussed in the interdisciplinary way which is otherwise impossible in a world of rigidly separated specializations […] the workshops were an organic part of a work of art (Honey Pump); but they were also a practical forum for the pressing issues of society”.[29]

4. The Political Commitment and the “Defense of Nature”

“I wish to go more and more outside to be among the problems of nature and problems of human beings in their working places. This will be a regenerative activity; it will be a therapy for all of the problems we are standing before”.[50]

5. Blackboards as Blueprints of the Creative Process

“Ecology today means economy-ecology, law-ecology, freedom-ecology […] we cannot stop with a kind of ecology limited to the biosphere […] the ecological problem is a result of the unsolved social question in the last century. Therefore I say the only thing, which works is again a sort of enlarging of the idea of ecology toward the social body as a living being”.[39]

6. Beuys’ Legacy

7. Beuys and OI Methodologies

8. Conclusions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Carson, R. Silent Spring; Houghton Mifflin: Boston, MA, USA, 1962; ISBN 978-0618253050. [Google Scholar]

- Meadows, D.H.; Meadows, D.L.; Randers, J.; Behrens, W.W., III. Limits to Growth; Universe Books: New York, NY, USA, 1972; ISBN 876631650. Available online: http://www.donellameadows.org/wp-content/userfiles/Limits-to-Growth-digital-scan-version.pdf (accessed on 29 July 2018).

- Turner, G.M. Is Global Collapse Imminent; MSSI Research Paper No. 4; Melbourne Sustainable Society Institute, The University of Melbourne: Melbourne, Australia, 2014; ISBN 978-0734049407. [Google Scholar]

- Keller, D.R. Deep Ecology. In Encyclopedia of Environmental Ethics and Philosophy; Callicott, J.B., Frodeman, R., Eds.; Gale, Cengage Learning: Farmington Hills, MI, USA, 2009; ISBN 978-0028661377. [Google Scholar]

- Jonas, H. Das Prinzip Verantwortung: Versuch Einer Ethik fur Die Technologische Zivilisation; Insel-Verlag: Frankfurt am Main, Germany, 1979; ISBN 978-3518399927. [Google Scholar]

- Jonas, H. The Imperative of Responsibility. In Search of an Ethics for the Technological Age; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1984; ISBN 978-0226405971. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Conference on Environment and Development. The Earth Summit: The United Nations Conference on Environment and Development; Introduction and Commentary Stanley P. Johnson; Graham and Trotman/Martinus Nijhoff: London, UK; Boston, MA, USA, 1993; ISBN 978-1853332753. [Google Scholar]

- Partridge, E. In Search of Sustainable Values. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. 2003, 6, 25–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development—A/RES/70/1; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Lehtonen, M. The environmental-social interface of sustainable development: Capabilities, social capital, institutions. Ecol. Econ. 2004, 49, 199–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chesbrough, H.W. Open Innovation: The New Imperative for Creating and Profiting from Technology; Harvard Business School Press: Boston, MA, USA, 2003; ISBN 978-1578518371. [Google Scholar]

- Murray, R.; Julie, C.; Geoff, M. The Open Book of Social Innovation; NESTA: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Eskelinen, J.; Robles, A.G.; Lindy, I.; Marsh, J.; Muente-Kunigami, A. Citizen Driven Innovation; World Bank Group: Washington, DC, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, T. Design Thinking. Harward Bus. Rev. 2008, 6, 84–92. [Google Scholar]

- Deblonde, M. Responsible research and innovation: Building knowledge arenas for glocal sustainability research. J. Responsib. Innov. 2015, 2, 20–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogers, M.; Henry, C.; Carlos, M. Open Innovation: Research, Practices, and Policies. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2018, 60, 5–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brabham, D.C. Crowdsourcing as a model for problem solving. Convergence 2008, 14, 75–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moysidou, K. Motivations to Contribute Financially to Crowdfunding Projects in Open Innovation: Unveiling the Power of the Human Element; Salampasis, D., Mention, A.-L., Eds.; World Scientific Publishing Co.: Singapore, 2017; pp. 283–318. ISBN 978-981-3140-84-4. [Google Scholar]

- Loorbach, D. Transition Management: New Mode of Governance for Sustainable Development; International Books: Utrechy, The Netherlands, 2007; ISBN 978-9057270574. [Google Scholar]

- Lerch, D. Six Foundations for Building Community Resilience; Post Carbon Institute: Santa Rosa, CA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Harlan, V. (Ed.) What Is Art? Conversation with Joseph Beuys; Clairview Books: East Sussex, UK, 2004; ISBN 978-1905570072. [Google Scholar]

- Harlan, V.; Rappmann, R.; Schata, P. Soziale Plastik: Materialien zu Joseph Beuys; Achberger Verlag: Achberg, Germany, 1976; ISBN 978-3881030120. [Google Scholar]

- Kuoni, C. Energy Plan for the Western Man: Joseph Beuys in America; Four Walls Eight Windows: New York, NY, USA, 1993; ISBN 978-1568580074. [Google Scholar]

- Bjelić, D. Art Is Social Capital: Toward Economy of Social Art. Interview with Joseph Beuys. Interkulturalnost 2014, 8, 195–200. [Google Scholar]

- Kort, P. Beuys: The Profile of a Successor. In Joseph Beuys, Mapping the Legacy; Gene, R., Ed.; Distributed Art Publishers, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2001; ISBN 978-1891024030. [Google Scholar]

- Beckmann, L. The Causes Lie in the Future. In Joseph Beuys, Mapping the Legacy; Distributed Art Publishers Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2001; ISBN 978-1891024030. [Google Scholar]

- Holland, A. (Ed.) Joseph Beuys & Rudolph Steiner: Imagination, Inspiration, Intuition; National Gallery of Victoria: Melbourne, Australia, 2007; ISBN 978-0724102914.

- Drechsler, W. Joseph Beuys in der Sammlung des MUMOK Kölner Mappe (64 Zeichnungen von 1945–1973); Verlag für Moderne Kunst: Nürnberg, Germany, 2006; ISBN 978-3938821725. [Google Scholar]

- Tisdall, C. Joseph Beuys; Thames & Hudson: New York, NY, USA, 1979; ISBN 978-0500091364. [Google Scholar]

- Steiner, R. Bees; Steiner Books—Anthroposophic Press: Barrington, MA, USA, 1998; ISBN 978-0880104579. [Google Scholar]

- Stachelhaus, H. Joseph Beuys; Abbeville Press: New York, NY, USA, 1991; ISBN 978-1558591073. [Google Scholar]

- Adriani, G.; Konnertz, W.; Thomas, K. Joseph Beuys, Life and Works; Barron’s Educational Series: Woodbury, NY, USA, 1979; pp. 88–89. ISBN 978-0812021752. [Google Scholar]

- Beuys, J.; Steidl, G.; Staeck, K. Joseph Beuys: Honey Is Flowing in All Directions; Edition Staeck: Heidelberg, Germany, 1997; ISBN 978-3882435382. [Google Scholar]

- Rothfuss, J. Joseph Beuys: Echoes in America. In Joseph Beuys: Mapping the Legacy; Gene, R., Ed.; Distributed Art Publishers, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2001; ISBN 978-1891024030. [Google Scholar]

- Beuys, J.; Böll, H. Free International University Manifesto. 1972. Available online: https://sites.google.com/site/socialsculptureusa/freeinternationaluniversitymanifesto (accessed on 29 July 2018).

- Kuspit, D. Beuys: Fat, Felt, and Alchemy. In The Critic Is Artist: The Intentionality of Art; UMI Research Press: Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 1994; pp. 345–358. ISBN 978-0835719278. [Google Scholar]

- Shulman Herz, R. Art, Pedagogy, and Participation: An Examination of Two Pedagogical Projects. Master’s Thesis, Hunter College, New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Walberg, D. Documenta 7 Free International University Beuys Veranstaltungskalender. 1982. Available online: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Documenta_7_Free_International_University_1982.jpg (accessed on 22 October 2018).

- Beuys, J. Appeal for an Alternative. Centerfold 1979, 3, 307. Available online: https://issuu.com/sethjordan/docs/beuys_appeal (accessed on 29 July 2018).

- Jordan, C. Appealing for an Alternative: Ecology and Environmentalism in Joseph Beuys’ Projects of Social Sculpture. 2016. Available online: http://www.seismopolite.com/appealing-for-an-alternative-ecology-and-environmentalism-in-joseph-beuys-projects-of-social-sculpture (accessed on 29 July 2018).

- Klimke, M. West Germany. In 1968 in Europe: A History of Protest and Activism, 1956–1977; Klimke, M., Scharloth, J., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 2008; pp. 97–110. ISBN 978-0230606197. [Google Scholar]

- De Duve, T. Joseph Beuys, or the Last of the Proletarians. October 1988, 45, 47–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rootes, C. The Environmental Movement. In 1968 in Europe: A History of Protest and Activism, 1956–1977; Klimke, M., Scharloth, J., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 2008; ISBN 978-0230606197. [Google Scholar]

- Frankland, E.G. Germany: The Rise, Fall and Recovery of Die Grünen. In The Green Challenge: The Development of Green Parties in Europe; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 1995; ISBN 978-0415106498. [Google Scholar]

- De Domizio Durini, L. Who Is Joseph Beuys; Venice International Performance Art Week: Venice, Italy, 2014; Available online: http://www.veniceperformanceart.org/index.php?page=230&lang=en (accessed on 29 July 2018).

- Beuys, J. 7000 Eichen—Stadtverwaldung Statt Stadtverwaltung/7000 Oaks—City Forestation Instead of City Administration; Documenta: Kassel, Germany, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Bunse, J. Documenta 7 Basaltstelen Beuys und Inschrift von Lawrence Weiner am Fries Fridericianum. 1982. Available online: https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/7/7f/Documenta_7_Beuys_Weiner_Fridericianum_1982.jpg (accessed on 22 October 2018).

- Baumapper. 7000 Eichen—Die Stelen. 2016. Available online: https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/9/9b/7000_Eichen-Stelen_08_2016-06-25.jpg/1920px-7000_Eichen-Stelen_08_2016-06-25.jpg (accessed on 22 October 2018).

- Stifftung 7000 Eichen Website. Available online: https://www.7000eichen.de (accessed on 22 October 2018).

- Demarco, R. Conversations with Artists. Studio Int. 1982, 195, 46. [Google Scholar]

- Conti, G. Joseph Beuys + Italy/The Defense of Nature. 2010. Available online: http://www.planum.net/joseph-beuys-italy-the-defense-of-nature (accessed on 29 July 2018).

- Mesch, C.; Michely, V. (Eds.) Joseph Beuys: The Reader; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2007; ISBN 978-0262633512. [Google Scholar]

- Moffitt, J. Occultism in Avant-Garde Art: The Case of Joseph Beuys; UMI Research Press: Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 1988; ISBN 978-0835718813. [Google Scholar]

- Lachman, G. Rudolf Steiner: An Introduction to His Life and Work; Penguin Publishing Group: New York, NY, USA, 2007; ISBN 978-1585425433. [Google Scholar]

- Anna, S. (Ed.) Joseph Beuys, Düsseldorf; Hatje Cantz: Ostfildern, Germany, 2008; ISBN 978-3775719926. [Google Scholar]

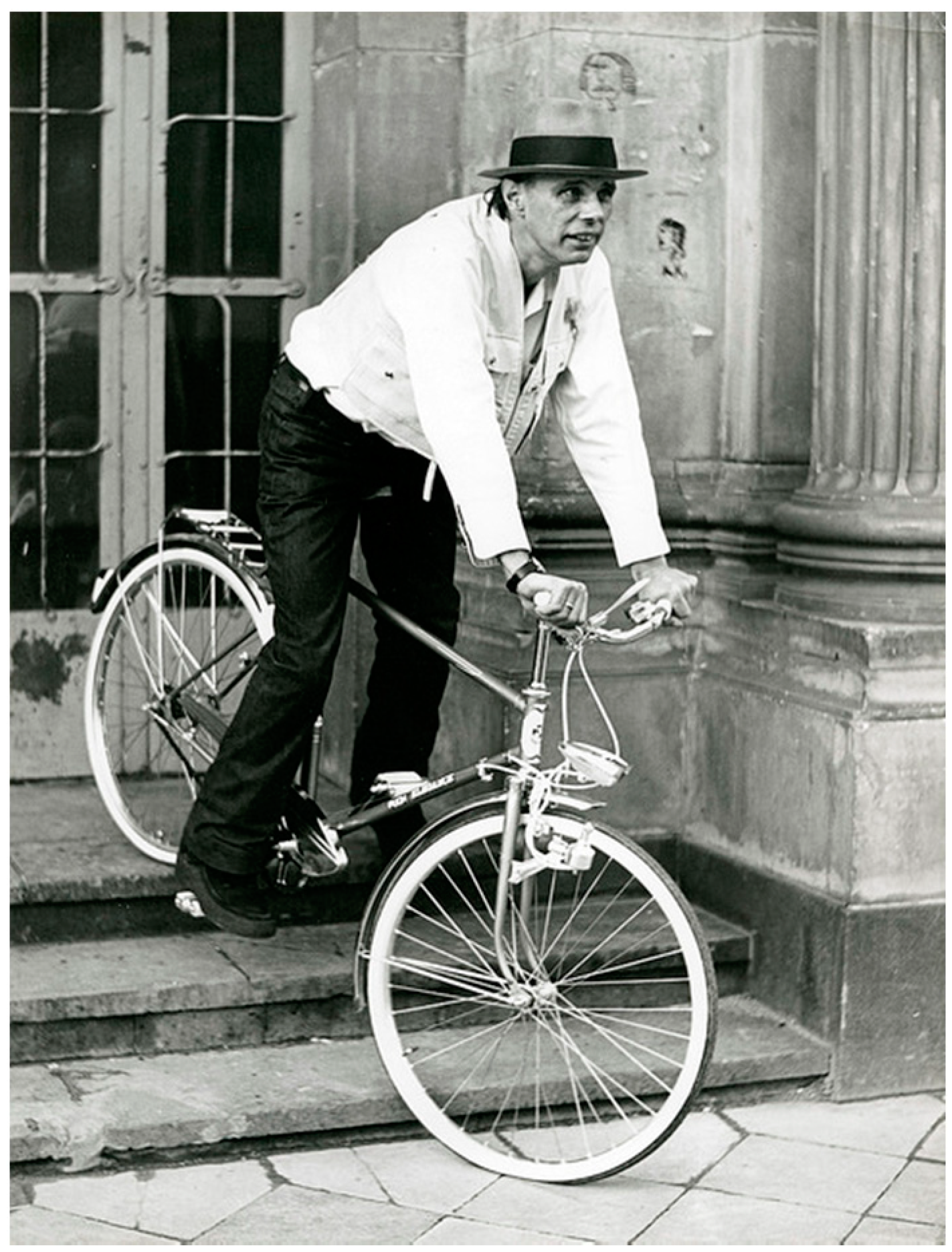

- Lachmann, H. Joseph Beuys—With a Bicycle on the Steps of the Kunstakademie of Düsseldorf. AEKR Düsseldorf 8SL 046 (Bildarchiv), 019_0073. Available online: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Josph_Beuys_-_mit_Fahrrad_auf_den_Stufen_des_D%C3%BCsseldorfer_Schlossturms_(27491576564).jpg (accessed on 22 October 2018).

- Rappmann, R. Joseph Beuys on His Lecture “Jeder Mensch ein Künstler—Auf dem Weg zur Freiheitsgestalt des Sozialen Organismus” in Achberg. 1978. Available online: https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/9/9b/BeuysAchberg78.jpg (accessed on 22 October 2018).

- Wildgen, W. Sculpture, Diagram, and Language in the Artwork of Joseph Beuys. In Investigations into the Phenomenology and the Ontology of the Work of Art; Bundgaard, P.F., Stjernfelt, F., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; ISBN 978-3-319-14089-6. [Google Scholar]

- Tomassoni, I. Beuys a Perugia; Silvana Editoriale: Cinisello Balsamo, Italy, 2003; ISBN 978-8882156497. [Google Scholar]

- Adams, D. Joseph Beuys: Pioneer of a Radical Ecology. Art J. 1992, 51, 26–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laderman Ukeles, M.; Durham, J.; Downes, R.; Fend, P.; Johanson, P.; Denes, A.; Curmano, B.; Vater, R. A Journey: Earth/City/Flow. Art J. 1992, 51, 12–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Social Sculpture Research Unit Website. Available online: http://www.social-sculpture.org (accessed on 29 July 2018).

- Sacks, S. Social sculptures and new organs of perception. New practices and new pedagogy for a humane and ecologically viable future. In Beuysian Legacies in Ireland and Beyond; Lit Verlag: Münster, Germany, 2011; ISBN 978-3825807610. [Google Scholar]

- Bolis, A. Les Plasticiens de l’Antarctique. Le Monde 11.01.2016. 2015. Available online: https://www.lemonde.fr/cop21/article/2015/11/27/les-plasticiens-de-l-antarctique_4819391_4527432.html (accessed on 29 July 2018).

- Bush, K.; Demos, T.J.; Francesco, M.; Jonathan, P.; Graham, S. Radical Nature—Art and Architecture for a Changing Planet 1969–2009; Buchhandlung Walther König: Cologne, Germany, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Winter, S.G. Toward a Neo-Schumpeterian Theory of the Firm; Working Paper P-3802; RAND: Santa Monica, CA, USA, 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Chalmers, D. Social innovation: An exploration of the barriers faced by innovating organizations in the social economy. Local Econ. 2012, 28, 17–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, M.L.; Westley, F. Surmountable Chasms: Networks and Social Innovation for Resilient Systems. Ecol. Soc. 2011, 16, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biddle, E. Re-Animating Joseph Beuys’ “Social Sculpture”: Artistic Interventions and the Occupy Movement. Commun. Crit. Cult. Stud. 2014, 11, 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banks, J.A. The Sociology of Social Movements; Macmillan: London, UK, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Drayton, W. Everyone a Changemaker: Social Entrepreneurship’s Ultimate Goal. Innov. Technol. Gov. Glob. 2006, 1, 80–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curley, M.; Formica, P. (Eds.) The Experimental Nature of New Venture Creation. Capitalizing on Open Innovation 2.0; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; ISBN 978-3319001784. [Google Scholar]

- The Ocean Cleanup Website. Available online: https://www.theoceancleanup.com/ (accessed on 22 October 2018).

- Precious Plastic Website. Available online: https://preciousplastic.com/ (accessed on 22 October 2018).

- Uniti Website. Available online: https://www.uniti.earth/ (accessed on 22 October 2018).

- Perotto, P.G. Il Paradosso Dell’Economia; FrancoAngeli: Milano, Italy, 1993; ISBN 978-8820478513. [Google Scholar]

- Ray, G. (Ed.) Joseph Beuys: Mapping the Legacy; Distributed Art Publishers, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2001; ISBN 978-1891024030. [Google Scholar]

- Tisdall, C. Joseph Beuys: We Go This Way; Violette Editions: London, UK, 1998; ISBN 978-1900828123. [Google Scholar]

- Riegel, H.P. Beuys Die Biographie; Aufbau Verlag: Berlin, Germany, 2013; ISBN 978-3351027643. [Google Scholar]

- Bateson, G. Steps to an Ecology of Mind; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1972; ISBN 978-0345273703. [Google Scholar]

- Saviour. Joseph Beuys’ Face on a Tram. 2008. Available online: https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/c/c2/Joseph_Beuys_on_a_tram.jpg (accessed on 22 October 2018).

| Social OI Feature | Description | Beuys’ Artwork Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Participatory mapping | Problems and opportunities are identified by community members as people are best placed to identify their own needs and express their own ideas or solutions. | Approach adopted in 7000 Eichen where the sites for planting have been mapped in cooperation with the citizens of Kassel according to their priorities on requalification of areas of the city. |

| Action research | This method encourages collective problem formulation and problem solving, replacing the usual relationship of “researcher” and “researched” with a more collaborative, iterative relationship where the emphasis is on research “with” as opposed to “on” people. Users are placed at the center of the process. | The whole FIU experience has been characterized by such approach. The FIU Manifesto rejects “the idea of experts and technicians being the sole arbiters in their respective fields.” They are requested to work in a “spirit of democratic creativity” together with nonexperts to discover “the inherent reason in things”. |

| Generative paradigm | Along a participated discussion, ideas lead to other ideas and the most fertile paradigms generate new hypotheses, expanding the insight and the possibilities. This feature requires a “creative ignorance” attitude, where the path of discovery leaves the knowledge maps of incremental innovation. Boundaries of fenced systems are overstepped by setting unprecedented connections through system thinking. Serendipity driven results are envisaged. | The symbolism of fat, as well as of the beehive, has been widely adopted to represent the transition from chaos to order, with the proceeding from disparate thoughts to a solid representation of a collective view. The Art–Science discovery process, substantiated by the blackboards, proceeds step-by-step from intuition to evidence, exploring possible connections and paths toward the Truth. |

| Design thinking | It is a methodology used to solve complex problems, finding desirable solutions for the users. The design mindset is not problem-focused but solution-focused and action-oriented toward creating a preferred future. Logic, imagination, intuition, and systemic reasoning are combined to explore possibilities of what could be and to create desired outcomes. | The Social Sculpture process anticipates the design thinking features. Especially in FIU workshops, a set of problems (global and local ones) were selected and proposed. Participants were asked to offer possible solutions arising from their knowledge, skills, and intuition. Organizers were facilitating the process, setting the conceptual framework, animating, and facilitating selection of the most promising ones and their further proceedings. |

| Community building actions | A group of people is driven to recognize a common goal regardless of the diversity of their backgrounds. Open and effective communication is set toward the common goals, establishing a sense of reciprocal safety. | We have reported the Piantagione Paradise project where the need of regenerating biodiversity has been shared with local communities that have been fully involved along the process. |

| Promotion of individual creativity | Individuals are stimulated to share their knowledge in a creative, collective effort. Intrinsic passion and interest in the goals are used as triggers, self-confidence is promoted in a nonthreatening, noncontrolling climate. Combination and recombination, such as the “intersection” among individual capabilities, is incentivized. | This is one of the most distinctive features of the Social Sculpture. Everyone can contribute to change and self-determination, transforming the everyday acts of life into an artistic act by combining physical and spiritual material. The scope of education and performances is essentially to promote this attitude. |

| Crowd-based approach | It can refer to “in-kind” contribution (crowdsourcing, as the practice of obtaining needed services, ideas, or content by collecting contributions from a large group of people) and “in-cash” contribution (crowdfunding, as a financing method to fund a project with relatively modest contributions from a large group of individuals, rather than seeking substantial sums from a small number of investors). | The Social Sculpture actions have been supported by a large in-kind contribution, in terms of shared knowledge, time and workforce. Crowdfunding of large scale projects has been implemented through the collection of contribution in change of small artworks. In the 7000 Eichen project, in addition to the initial funding provided by Dia Art Foundation, further sources included individual tree sponsorships, donations from many other artists as well as significant contributions by Beuys himself. |

| Multidisciplinarity | It is the attitude of combining several academic disciplines or professional specializations in an approach to a topic or problem. | Events like 100 Days of Free International University are fully coherent with this feature. Participants and invited experts were coming from different disciplines and professional domains. The approach adopted for the discussion was topic oriented, mixing the different contributions during the “search for truth”. |

| Disruptive and scalable innovation | Disruptive innovation is the introduction of a product, service, or operational model into an established field where it performs better than existing offerings, thereby displacing leaders in that particular field. Scalable, even exponentially, solutions and organizations are expected and promoted. The assumption is that if a problem has been solved by someone and the solution works, it should be globally scaled up. | Beuys is affording global challenges, and his action is aimed at establishing a symbolic reference and an open methodology to scale-up. In the Defense of Nature, replantation artworks are just the beginning of a global action extended to the regeneration of the whole planet. |

© 2018 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Montagnino, F.M. Joseph Beuys’ Rediscovery of Man–Nature Relationship: A Pioneering Experience of Open Social Innovation. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2018, 4, 50. https://doi.org/10.3390/joitmc4040050

Montagnino FM. Joseph Beuys’ Rediscovery of Man–Nature Relationship: A Pioneering Experience of Open Social Innovation. Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity. 2018; 4(4):50. https://doi.org/10.3390/joitmc4040050

Chicago/Turabian StyleMontagnino, Fabio Maria. 2018. "Joseph Beuys’ Rediscovery of Man–Nature Relationship: A Pioneering Experience of Open Social Innovation" Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity 4, no. 4: 50. https://doi.org/10.3390/joitmc4040050

APA StyleMontagnino, F. M. (2018). Joseph Beuys’ Rediscovery of Man–Nature Relationship: A Pioneering Experience of Open Social Innovation. Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity, 4(4), 50. https://doi.org/10.3390/joitmc4040050