Abstract

The family business is one of the world economy’s leading drivers, playing a significant role in countries’ economic and social development. Portugal is a country very dependent on this type of companies, which makes this study important, not only for discussing the problem in this scientific field but also for understanding family business characteristics in a country so dependent on this type of business. In this sense, this research work’s general objective is to understand the reality of the management of family businesses in the footwear industry, through the vision of the CEO’s of five companies in the North of Portugal. The present study is qualitative, as interviews were carried out with five CEOs of family businesses. The authors collected the participants’ reports between June and July 2019, in a single moment, through a face-to-face interview held at their respective workplaces, after prior scheduling. The interviews were recorded using an audio recorder and later transcribed and imported for analysis. The results obtained demonstrated that these organizations contribute enormously to the country’s economic and social development. This study also contributes to improving the understanding of the subject under analysis, through interviews with CEOs in the footwear industry in the Northern region of Portugal, exposing in more depth this representative and emerging sector, in a country mostly characterized by family businesses. It also aims to contribute to understanding the main determinants and characteristics of family businesses in the literature, like family businesses and performance, namely, ownership, professionalization, company–family relationship, succession, management and performance practices. With this study’s results, it is also expected that they may be susceptible to discussion and comparison with family businesses from other countries and from different business areas.

1. Introduction

Family businesses are possibly one of the oldest forms of activity that emerged throughout humanity’s evolution [1]. According to Lodi [2], a family business (FB) is one in which the management succession process is linked to the hereditary factor and where the company’s institutional values are identified by the surname or the figure of the founder. Despite the numerous studies carried out, the concept of FB is not widespread or known to everyone, and most people believe that a FB is one that was founded by a single individual or several, and where most of its family members perform functions [3].

Studies on this type of company are already underway. However, they have not always been seen in the best way [4]. There is still no clear definition in terms of performance nor a consensus among researchers [5]. The proof of this is the lack of consensus around the definition of FB [6]. As a result of this ambiguity and lack of uniformity around the concept of FB and its determinants, the European Union carried out a study [7], developed by a group of experts in the field and representative of all its member states, in which a definition of FB was established after having identified more than 90 definitions of the family business. However, after the Litz study [8], and several years after the completion of the European Union study, “Family businesses in the North: Cartography, Portraits and Testimonies”, 2018, developed by the University of Minho, was identified as a threat to the “Non-stabilization of the definition of Family Business”, even though between 65% to 80% of the world’s companies are family members, from the smallest to world-renowned companies [9]. Rock [4] says that the problem is related to the fact that the breadth and dimension of control and its interests remain mysterious, referring to them as “private companies in the broadest sense of the term”. In Portugal, 80% of companies are family-owned and generate 60% of the gross domestic product, accounting for 50% of employment [10], which reinforces their dependence on this type of companies. However, little is yet known empirically about their determinants [11].

Within the scope of Portuguese family businesses, there are about 1500 footwear companies in Portugal, of which 75% are within a 60 km radius between Felgueiras and Oliveira de Azeméis. This industry has been improving from year to year, improving its indicators and its impact on the Portuguese economy, which today accounts for 3.2% of the national manufacturing industry’s gross added value and 6.8% of employment. In Portugal, footwear has an annual turnover of just over 2 billion euros, with 95% of this resulting from exports [12].

Even though these studies help realize the important contribution of FB in the local and global economy, a gap is still perceived concerning their definition and way of acting [13].

The general objective of this research is to study the characteristics of family businesses as well as the impact they have on their form of management. To achieve this general objective, two specific objectives were outlined: (1) To carry out a systematic review of the literature on this area of knowledge, and (2) to carry out a case study, of a qualitative nature, in order to understand the reality of the management of family businesses in the footwear industry through the vision of the Chief Executive Officers (CEO’s) of five companies. In this sense, this study aims to contribute to improving the understanding of the subject under analysis, through interviews with CEOs in the footwear industry in the Northern region of Portugal, exposing in more depth this representative and emerging sector, in a country mostly characterized by FB [14]. It also aims to contribute to understanding the main determinants and characteristics of FB until now in the literature [5].

The results of the study revealed that family business and performance management is a subject of great importance for analysis and there are more and more research studies that approach it from the most diverse perspectives. Researchers have shown a growing interest in the subject, producing more and more research of strong academic impact in this area of knowledge. Another evidence that this study has shown us was to inventory and analyze the main topics addressed by the authors, highlighting the following topics: family business, performance, business, management, property, research. The fact that Portugal is a country very dependent on this type of companies makes this study important, not only for discussing the problem in this scientific field but also for understanding FB’s characteristics in a country so dependent on this type of business. With this study’s results, it is also expected that they may be susceptible to discussion and comparison with FB from other countries and from different business areas.

This study is structured in six parts, the first consisting of the Introduction, where the problem is contextualized, the gap identified, and the study objectives are presented. Then, in the Systematic Literature Review, the most discussed topics in the literature on FB are reviewed. Subsequently, the Methodology presents the method used, the participants and the analysis process. Next, the Results and Discussion Section contains the main outputs generated in this study and their interpretation. The next point refers to the Conclusions, where the main understandings of the study are exposed. Finally, the Limitations and Suggestions for Future Research are presented, making reference to the study’s main limiting questions which need to be explored in the future.

2. Systematic Literature Review

A bibliographical review of theoretical and empirical articles was carried out using strictly qualitative research to study the subject. The nature of the systematic review study is eminently theoretical, with the advantage of enabling synthesis of studies in underdeveloped areas of investigation [15] and providing solid and reliable evidence that will allow the triggering of future studies on a given theme [16]. Thus, this analysis allows a compilation of the studies carried out and allows identifying topics that may serve as a basis for future research [17].

According to Agarwal [18] (p. 813), “a systematic review is the process of searching, selecting, appraising, synthesizing and reporting clinical evidence on a particular question or topic. It uses a methodology of clearly-designed questions and methods to identify and critically evaluate relevant research, followed by the collection and analysis of data from the studies that are included in the review”.

Gil [19] and Markoni and Lakatos [20] argue that the systematic review of the literature is a research carried out from the published bibliography related to a specific theme, based, as such, on secondary sources. Martins and Theóphilo [21] consider that such research promotes the explanation and discussion of a given subject, theme or problem from the references published in different media, such as books, newspapers and magazines. It represents a method of mapping uncertainty areas, aiming to identify where little or no relevant research has been done, but where further studies are needed [22].

The systematic literature review employs a specific methodology to locate research to select and evaluate the contributions made by each study and analyze and synthesize the data [23]. For Denyer and Tranfield [16], it consists of a specific methodology that locates existing studies, selects and evaluates contributions, analyzes and synthesizes data and reports the evidence in such a way that allows reasonably clear conclusions about what is and what is not is known. These authors suggest five stages in conducting a systematic literature review, namely establishes the focus of the review through research questions (Stage I), locates and selects the literature that is relevant to the research questions (Stage II), includes a set of explicit selection criteria to assess the relevance of each study found (Stage III), breaks down research into relevant parts and makes associations between these parts identified (Stage IV) and includes a summary (Stage V).

According to Vergara [24], the systematic literature review is the systematized study of publications of a different nature (books, magazines, newspapers, electronic networks, theses and dissertations, communications presented at congresses/conferences, among others), providing information for carrying out other types of research. For Nolan and Garavan [25], it is a methodology to examine and organize the current empirical and theoretical literature systematically. Agarwal [18] and Short [26] consider that this type of study, when organizing, evaluating and integrating scientific evidence, provides essential information and different points of view for the different users of the information. For Martins [27], the systematic review of the literature aims to collect, select, analyze and critically interpret the existing scientific contributions on a given subject or problem, allowing a review of the evidence on a formulated question. According to Sampaio and Mancini [17], it is possible to identify themes that need further investigation through such methodology.

In the systematic review, specific criteria should be established that provide relevance and quality for selecting studies to make them transparent to those interested [16,17,28]. This paper’s systematic review was divided into three phases: planning, execution/conducting the review and analysis. In the planning phase, it was intended, through the main objective, to select studies that addressed the theme; in the execution, the articles initially selected were evaluated in order to eliminate those that do not fit, and, finally, in the analysis phase, the articles resulting from the previous selection were identified and analyzed [28,29].

The collection of information was carried out by consulting a specialized bibliography: books and papers carried out on the subject. In the execution phase, the starting point was to identify the existing bibliography on the topic using keywords to identify and categorize the information found, namely “family business”. In this stage, exploratory reading was used in order to verify whether the articles were relevant to the study [19]. According to Tranfield et al. [28], this phase should be capable of replication and therefore needs to be detailed, being necessary to compile the research in a list of articles that were the basis of the review. To assist in the transition between the execution and analysis phase, we resort to the bibliography’s selective and analytical reading. In the selection process, the objective of the research was taken into account in order to verify whether the texts contribute to solving the initial problem, the analytical objective was to synthesize the previous information, and there may be a need to incorporate new texts or suppress those previously selected [19].

A general search made on any academic search engine or database of articles on family business management, shows an extensive amount of published studies and studies in various disciplines and research areas. In this article, a systematic approach was used to perform the literature review and map the most relevant research studies, using a rigorous research protocol and refinement criteria. They defined concrete steps of research execution and literature analysis based on scientific articles published in the Institute for Scientific Information (ISI) Web of Science database, using the keywords “Family Firms Management and Performance” and “Family Business Management and Performance”. The articles identified, related to family firms management and performance, are located in a timeframe between 1997 and 2018. The purpose of this literature review section was to contribute to more knowledge of this theme and, consequently, of the literature related to it, both concerning the scientific community and professionals in the field.

2.1. Family Business Main Topics

The themes under study come from an exhaustive study of the literature on family businesses and the dimensions that influence them. The dimensions that stood out were management practices and succession, performance, the interrelationship of family–business systems, professionalization and property.

Succession represents one of the most critical moments experienced in the context of the company and the business family, marked by the transfer of power and control of the business (or the loss of it) among the heirs [30].

Due to the difficulty of a harmonious succession in family businesses, only a small percentage of family businesses succeed in the next generation. The CEO’s succession decision is essential for a smooth transition in top management position and success in family businesses [31]. Succession is presented as one of the most important strategies determining a company’s longevity [32].

Management practices are an important dimension in family businesses and strategic planning, and the company’s future plays a critical role in FB´s life and growth [33]. However, there are other characteristics present in the management model that can compromise the quality of management, such as the lack of clear objectives [34], the inability to anticipate or adjust to environmental changes [35], the absence of financial planning systems [36], or the misuse of the company’s resources as a source of family financing [36].

Regarding performance, according to Astrachan at al. [37], a family business can be influenced by ownership, the type of management, the involvement in management and the legal, political and economic dimensions of the country which have a significant influence on performance. For example, small and older FBs show more significant concern with business performance because it enables increases in family socio-emotional wealth [38].

Pindado and Requejo [39] state that FBs have a significant performance compared to non-FBs due to concern about the company’s reputation and exceptional knowledge by families.

Concerning property, Astrachan [40] notes that the importance of ownership, control of property, ownership orientation, dilution of property and governance mechanisms to regulate the effect of separating ownership from control have aroused much interest over the past two decades.

A key feature that distinguishes the family business from public companies is the multiple roles family members play within the family and the company [41,42]. This role-diversity combined with the tangle of ownership and control affects corporate governance structures and leads to requirements compared to their non-family counterparts [43,44,45].

The relationship between business and family is often said to be “fertile ground for conflict” [46,47] or tormented by conflict [48]. The relationship between the family and business systems opens space for several disagreements, such as rivalries between family members [48], struggles over the inability to balance work and family needs [49], marital disagreements [50], or disputes over the division of family property [51].

Finally, Freitas and Frezza [52] describe professionalization as “a process by which a family or traditional organization assumes personalized practices”. It seems that it is a process where there is the integration of hired managers, among family managers. Regarding the need for professionalization in family businesses, this arises essentially with the advancement of generations in the company and the need to abandon the founder’s more paternalistic issue and guide the company to a more professional approach to all its dynamics. In the professional approach, two great valences stand out: strategic planning and improvement of management techniques [53]. The process of professionalization encompasses many different aspects that a company must address, such as the development of a sound corporate governance structure, including a board of directors and possible other governance bodies needed to supervise and control the company [54].

2.1.1. Performance

According to Astrachan et al. [37], a family business can see its performance influenced by ownership, the type of management, the involvement in management, the country’s economic policies and its legal dimensions. A company’s performance level can be conditioned by different competition types, namely growth opportunities and market forces [55]. Some familiar characteristics, such as philosophy and the way the company starts, can also affect its performance [56].

The company’s size can play an important role in economies of scale and the ease they can have in hiring more and better managers [55]. However, when analyzing this problem, we can separate family businesses into small and large companies, where in small companies we see an evident concern with performance, as this can bring increases in socio-emotional wealth, contrary to large companies, where ownership is usually dispersed, which makes the family identity present in the company more tenuous, thus being able to assimilate the performance in these companies to non-family companies [38].

However, the generation running the company directly influences the relationship between the concentration of ownership and business performance [57].

Following the differences between FB and NFB (non-family business), Pindado and Requejo [39] claim that FB tends to outperform because they are more concerned with their reputation, and consequently the company’s reputation, in addition to the in-depth knowledge of the company. In this sense, Anderson and Reeb [58] and Villalonga and Amit [59] found that only when the founding CEO or a non-family CEO is in the office is the FB’s performance superior to that of the NFB. In turn, in his study, Andres [60] reinforced that FB performance is exceptionally high when the founder is still active, performing the CEO’s functions.

Based on this understanding, it can be seen that the concentration of ownership makes performance emerge, as it allows greater clarification and consistency of objectives. However, this only occurs when the founder is active because as the property disperses, the objectives become less clear. The differences between descendants usually influence decision-making, which can have serious consequences [61].

More recent studies state precisely the opposite, proving that it is the founder and his management that tends to destroy its business value, and consequently, its performance reduction [38]. Basco [62] classified performance in two dimensions: 1—the economic performance centered on the company, and 2—the economic performance centered on the family.

2.1.2. Management Practices and Succession

Strategic planning and the company’s future play a critical role in FB life and growth [33]. However, it is impossible to dissociate the company’s strategy from that of the family, as its execution allows reaching family goals, such as, for example, control and low indebtedness. According to der Stede [63], control systems serve two purposes: strategy control and management control. Concerning FB management, Werner [64] mentions positive and negative points, highlighting the founder’s qualities positively and negatively in the succession processes. However, there are other characteristics present in the management model that can compromise the quality of management, such as, for example, the lack of clear objectives [34], the inability to anticipate or adjust to environmental changes [35], the absence of financial planning systems or the misuse of company resources as a source of family finance [36].

According to Leone [30], succession is characterized as the ritual of transferring power and capital between generations, to which the company currently directs and which it will manage in the future, which may be planned and happen gradually or else due to death or disability of the current leader of the company.

Through the combination of four phases: foundation, growth, heyday and decline, we can define a family business [2]. The decline phase is often coincident with the succession process, and this is a problem that has been going on since the beginning of the study of family businesses, as we can see when analyzing what Scheffer [65] wrote, where we found that at the time, most companies that were in the process of succession were also going through a difficult period, where conflicts emerged and where all kinds of resistance to decisions emerged mainly involving family members. According to Oliveira [3], dealing with the succession process in an anticipated and inherently safer way is far from being a habit of family businesses, whether small, medium, or large. This is mainly in the first generation. According to Bernhoeft [66], the absence of this habit can be explained by the extreme complexity of the moment from which reasons emerge, such as the divergence between partners, excessive number of successors and successors’ lack of interest in the business or disagreements between family members.

Sprungli [67] lists the difficulties of family businesses, calling them “ten deadly sins”, sins that, if not working, would generally put the company’s security at risk.

However, when the succession process is well-executed, it ceases to be a potential weakness and gives an opportunity. Planned and well-succeeded successions often result in closer ties between all family members and contribute to the company’s growth, combined with a joint vision and mission [68].

2.1.3. The Interrelationship of Family Business Systems

Deniz and Suarez [69] state that it is necessary to understand the family subsystem’s interactions and the business subsystem to understand family organizations. In turn, Lethbridge [70] states that it is possible to have positive results and achieve success as long as one has a clear perception of the advantages and disadvantages inherent in the relationship between family and company.

To better understand the interaction between subsystems, it is necessary to go to the beginning of family businesses, which, according to Oliveira [71], arises from the proactivity of a particular person who wants to start his own business and has the support of his family. This person tends to be a founder with robust personal characteristics and an in-depth knowledge of the business, which leads him to continue the business in the difficult first years of existence [70]. What turns out to be easily noticeable is the almost umbilical relationship between the company and its founder [72].

Ussman [72] also mentions that this connection has an absolute value for the company due to its founder’s dedication. However, in many cases, it also causes problems that limit the company’s growth, for example: the lack of setting goals, or the absence of strategic planning and the consequent lack of control over it.

Moreira Jr and Neto [73] characterize FB as being companies where there is a centralization of power, much the result of the effort and commitment of its founder in the early years that lead him to centralize all company decisions within himself, even when it is already structured more capably and professionally. However, the existence of the founder within the company has an end in sight, as he cannot be eternalized within the structure, which leads to the succession process being triggered, and usually for the generation following the one in office, even though this is often not the will of the successors [72].

With or without a will, what is correct is that the property does not qualify the administrative capacity, which usually causes problems within the FB, because their administration does not always follow the rule of meritocracy or competence to perform the functions [74].

This claim by family members and the continuity of administration within the family can be explained by Lethbridge [70], who characterized traditional FB as privately held to non-family members, with little transparency in providing financial information about the company.

Gallo and Sevilhano [74] say that there are two pitfalls for FB, the first referring to the remuneration of family members who tend not to follow the market rules. The second refers to the non-separation of affective ties with the company’s contractual relations. Despite not being exclusive to FB, the kinship relationship makes decision-makers’ emotions often influence their decision-making [73].

2.1.4. Professionalization

Professionalization is understood as a management process in which control is no longer exercised by the family that owns the company, passing to the hands of professional managers, where, among others, meritocratic values, formalized structures and independence of decisions predominate [75,76,77,78].

Freitas and Frezza [52] describe professionalization as “a process by which a family or traditional organization assumes personalized practices”. It can be perceived that it is a process in which there is an integration of contracted managers and family administrators.

In the case of Gehlen [79], he mentions that “professionalization begins to occur when the organization stops being just a family business to become a professional company”. However, Freitas and Frezza [52] warn that management’s professionalization is not immune to family influences. However, for the success of a good professionalization of the family business, it is necessary that the family managers that integrate it have the necessary qualifications and competences for the exercise of their functions. In cases where family members do not meet the requirements, recourse to professionals outside the family is inevitable, so that the company does not suffer from their incompetence [80].

Regarding the need for professionalization in family businesses, this arises essentially with the advancement of generations in the company and the need to abandon the founder’s more paternalistic nature and orient the company towards more professional approach dynamics. In the professional approach, two significant aspects stand out, strategic planning and the improvement of management techniques [53].

One of the problems with this professionalization may be the lack of understanding between the hired manager and the family that controls the company. The values and ideals may not necessarily be the same. When this situation is a reality, the attempt to professionalize the family staff may be an alternative. Usually, the values are the same, and the family’s control will be more effective [81].

According to the literature on the professionalization of family businesses over the years, this has systematically “pushed” the issue of hiring professionals from outside the family for management positions within the company, which leads us to assume, mistakenly, that within families, there are no managers with professional skills [82,83,84]. Even more worrying are professionalization results through members outside the family, where we find authors who say that the measure is positive [85,86,87]. Other authors argue that there is a negative effect on the measure [58,88,89], and in the case of some studies, they do not establish any cause–effect relationship [90,91].

Several authors defend complementary professionalization measures, which do not only involve the hiring of managers external to the family, such as the introduction of performance evaluation systems and the attribution of compensation through incentives [92], financial control systems [76] or, for example, a more formal way of recruiting, especially when it involves family members [93]. In addition to all these complementary measures, we can also start with the formal management mechanisms, which are among many ways to professionalize family businesses by creating boards of directors [54,77,78]. On the other hand, we have the decentralization of authority and the delegation of control as another form of professionalization of the company [92]. However, Stewart and Hitt [77] refer to how professionalization still lacks a singular meaning in academic and popular discourse.

2.1.5. Property

When studying property, and mainly property related to family businesses, it should be noted that approximately two-thirds of private companies are family-owned [42]. Some authors argue that family businesses perform better and others argue precisely the opposite.

The ownership structure can be distinguished into two main types, the concentrated and the dispersed [55]. Dispersed ownership can induce managers to adopt free-riding behavior but enable gains in risk diversification and superior knowledge of the market and labor [55]. As the property disperses, some of the initial characteristics of FB tend to change. In terms of research and development, investments can no longer be made from a long-term perspective and, as a result, carry fewer risks [94]. It can also boost an existing tension in the company; that is, it can foster sibling rivalry and disagreement between old and new generations [95].

San Martin-Reyna and Duran-Encalada [96] proved that, in Mexican companies, the increase in ownership concentration is a factor associated with business performance.

La Porta et al. [97] provide evidence that the more shareholders, the greater their control within the company, thus extracting as much benefit as possible from it.

Concentrated ownership makes it possible to resolve the conflict between shareholders and directors, since the majority shareholder is the CEO, who either has absolute control of the company or monitors the manager, thus enabling improved performance [98]. The concentration of ownership in family managers influences performance as both variables to influence investment, strategy and business growth opportunities [55]. Other authors claim that those same shareholders who own the concentration of ownership of the company tend to exchange the company’s profits for private benefits, which leads them to not maximize their profits and leaves them at a disadvantage for non-family businesses, as these genuinely separate what company profits are, with the financial preferences of the owners [99,100,101,102,103,104].

Villalonga and Amit [59] show that family ownership creates value only when the founder acts as the company’s CEO or as its president, and when the dispersion of ownership exists, the company’s value tends to decrease.

3. Methodology and Participants

3.1. Method

The present study is qualitative, as interviews were carried out with five CEOs of family businesses for further analysis and comparison with the literature. Given the exploratory nature and the starting point of this study, the type of investigation adopted was qualitative, using a case study method used to obtain a more in-depth understanding [105] about the reality of the management of family businesses from the CEO’s point of view, analyzing the main dimensions that affect the management of this type of companies and their performance. When a scientific field still needs more exploration and interpretation and is still little explored, with a substantial shortage of preliminary research on it, exploratory case studies are recommended [105]. In this sense, methodological procedures are essential in a case study, which implies that the research questions are correctly supported by the literature review [105]. The questionnaire used in these studies is semi-structured and was constructed based on the topics covered in the literature review. This study focuses on five family footwear businesses based in the Tâmega and Sousa region of North of Portugal. These companies were selected as they have characteristics that adapt to the intended study. From the several contacted, the included companies were the only ones in which the CEO agreed to the interview. The participants’ reports were collected by the authors, between June and July 2019, in a single moment, through a face-to-face interview held at their respective workplaces, after prior scheduling. The interviews were recorded using an audio recorder and later transcribed and imported for analysis.

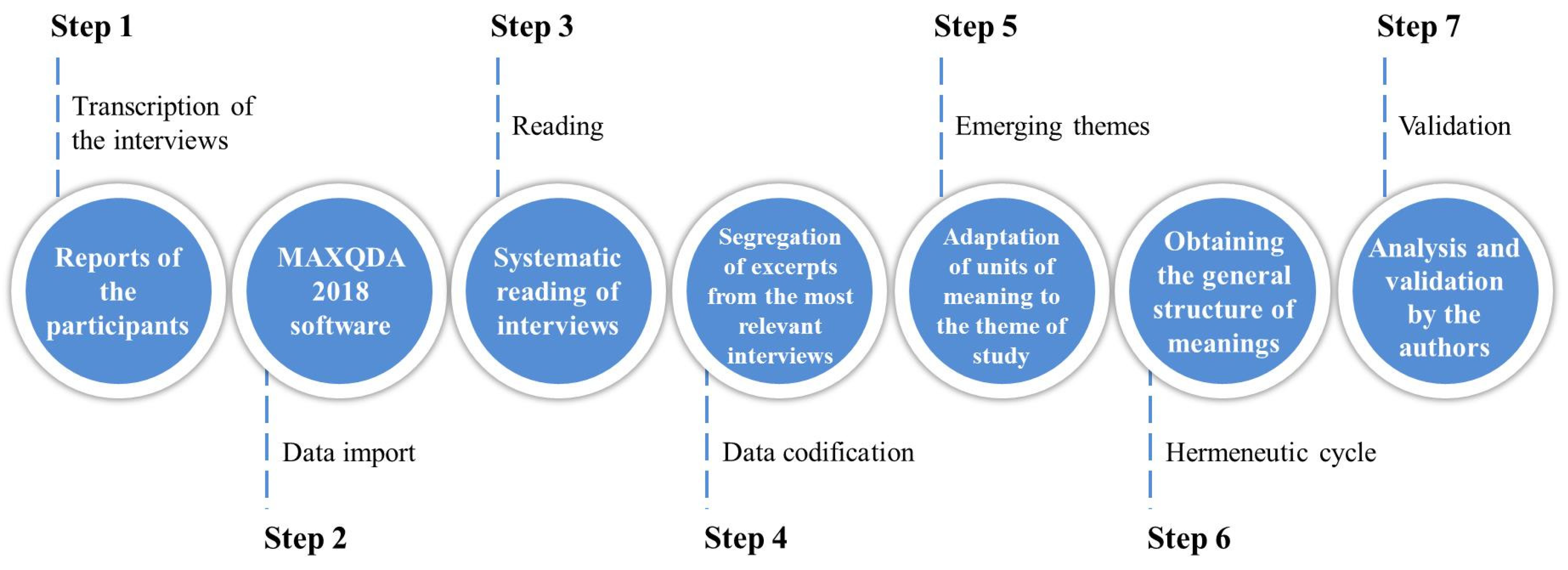

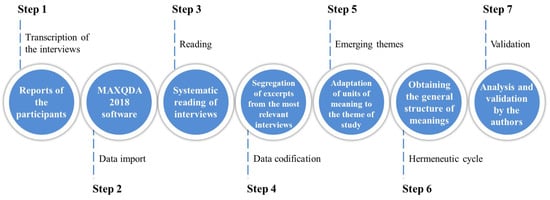

The content analysis of the interviews was based on the basic principles that characterize the method of interpretative phenomenological analysis (IPA), recurrent in qualitative studies in social sciences [106,107]. IPA is a type of systematic research of personal experience [108], its main objective is to understand the lived experiences in the first person, exploring how individuals give meaning to their personal and social universe through the meanings they attribute to their experiences [109]. Based on this understanding, this analysis process is used to highlight the individuals’ lived experience, based on the study of their perceptions [106,110]. In this research, the IPA method proved to be essential in conducting the study, as well as in the process of collecting individual interviews. In turn, the interviews’ content was interpreted according to the themes that emerged through the literature, creating relationships between them. Through this process, in this study, we seek to provide further consistency to the content of the interviews, providing a better understanding of the themes associated with FB. Using this methodology was also intended to guarantee more accurate results and impose greater clarity on them. Figure 1 helps us to understand the analysis process adopted by the authors.

Figure 1.

Description of the analytical process. Source: adapted from Smith et al. [106], elaborated by the authors.

3.2. Participants

Although there are several manuals of methodological procedures for research in social sciences, the case study follows its methodological perspective, and there is not only one method for data collection [111]. In this sense, the sources of empirical evidence used in this study, in an exploratory case, were semi-structured personal interviews (primary sources). The semi-structured interview is one of the most used qualitative research methods, aiming at a complete understanding of a given social phenomenon, based on the interviewees’ personal experiences [112].

For this case study, five interviews were conducted, based on questions that resulted from the literature review (Appendix A), with the hereafter named CEO1, CEO2, CEO3, CEO4 and CEO5. Despite authorizing the recording of the interviews, they did not authorize their identification in this research work. Table 1 shows the profile of the interviewees.

Table 1.

Interviewee profile.

3.3. Data Analysis

The interviews’ content analysis was carried out using the MAXQDA18 software (VERBI Software GmbH, Berlin, Germany), allowing the more efficient analysis of the interviews’ content, emphasizing emerging themes and units of meaning. This software is appropriate for analyzing all the data commonly collected in the context of the social sciences, improving its understanding [113]. In general, it allows systematically indexing and automatically encoding large volumes of text, proving to be an important tool in conducting content analysis [113]. In the process of interpretation and evaluation of the units of meaning, MAXQDA18 made it possible to classify the data in groups, systems of categories or codes, giving a more structured view of the content under analysis. It is still possible to present these results through tables or maps that improve understanding of qualitative data [113]. Thus, using MAXQDA18, the most relevant excerpts from the interviews (meaning units) were coded according to the theme under analysis, later converting them into relevant expressions (emerging themes). Thus, it was possible to interpret the results to establish hierarchies and assumptions between the codifications. It should be noted that the fact that the results come from a process of interpreting the interviews reveals some subjective character.

To obtain greater consistency, and the maximum verisimilitude of the interpretations, circular logic of conjecture and validation was adopted that governs the hermeneutic principle [114]. Then, to obtain a greater congruence between the proposals of emerging themes and units of meaning, a new content analysis of the interviews was carried out.

3.4. Cohesion between Reports

Using qualitative analysis software, the cohesion between the participants’ reports was analyzed through the correlation between the units of meaning and the emerging themes. According to the software outputs (Table 2), there is a strong correlation (close to 1) between respondents’ various contributions to this research study. The closer the correlation is to 1, the more significant the interviews’ contribution to understanding the phenomenon under analysis

Table 2.

Similarity Matrix.

4. Results

This study’s main objective was to analyze the individual testimony of five CEOs of family businesses, in the footwear industry, about their merits and the difficulties they encounter when managing a FB. In specific terms, it was intended to understand the day-to-day management of these CEOs and the main implications that the fact that the company is family had in the conduct of their work, as well as to understand the level of preparation that the CEO had, for the particularity of the company is familiar, and if that changed the way they manage and prepare themselves, or if it was indifferent to them.

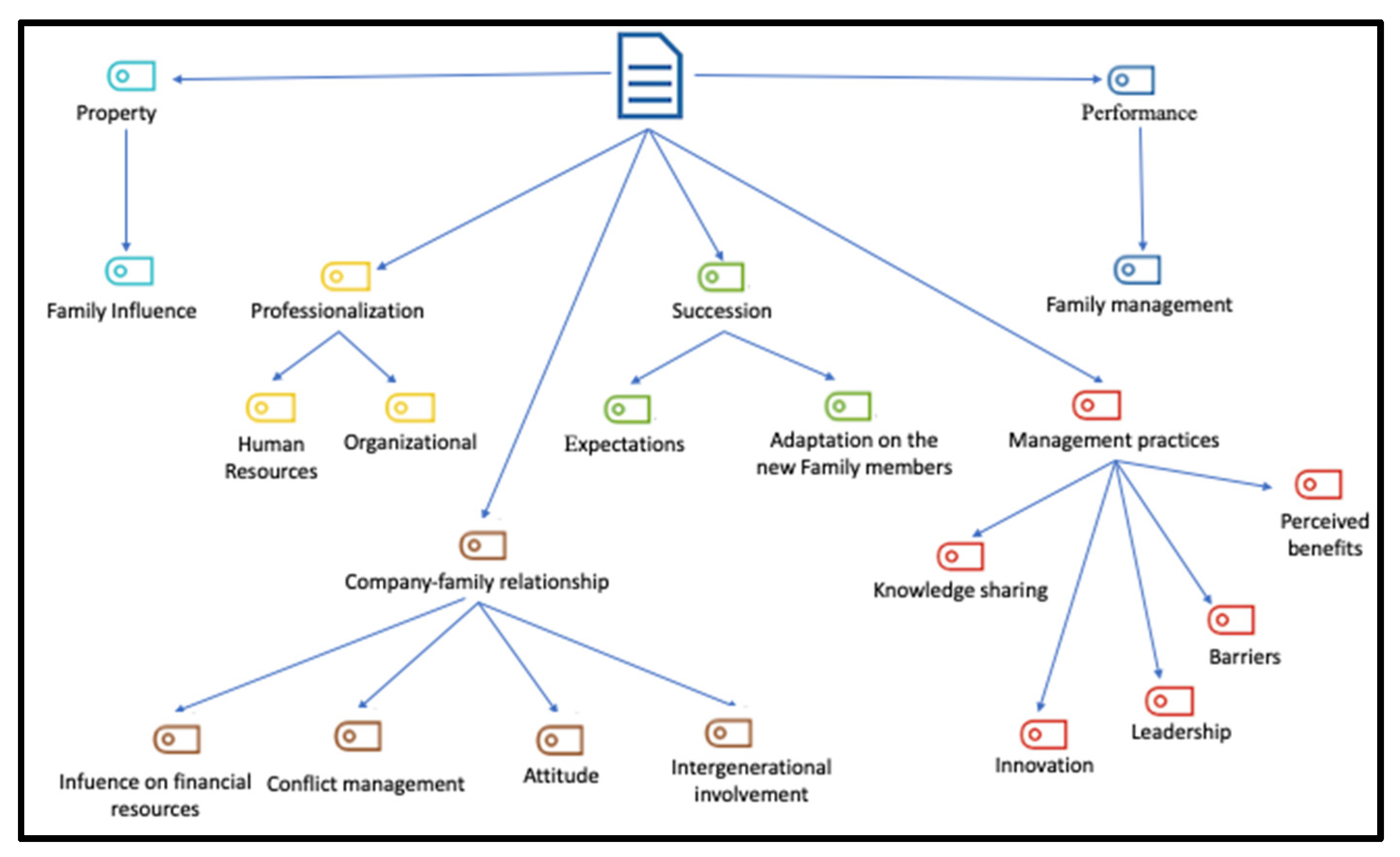

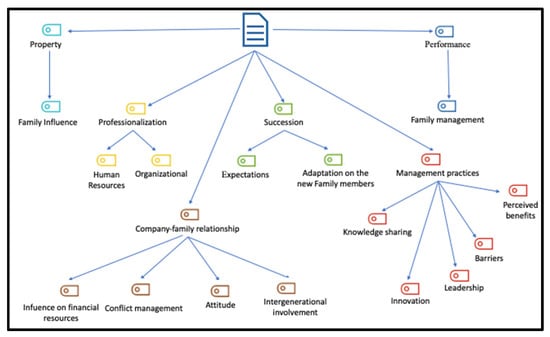

The semi-structured interviews’ content analysis showed the main emerging categories that arise from the content analysis, characterizing the interviews conducted according to their occurrence (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Global category map. Source: elaborated by the authors.

Table 3 summarizes the content of the units of meaning attributed to the content analysis of the interviews. After the detailed and systematic analysis of the data collected, it was confirmed that there is a straightforward approach on the part of the participants, to the main themes that are associated with the management of family businesses which are: succession, professionalization, ownership and family business relationship, management practices and performance.

Table 3.

Structure units of meaning.

According to the respondents’ answers, the property is extremely important for the company’s continuity in the family when it comes to family influence. The words “honor” and “pride” stand out in the CEO responses. It is practically unanimous that the fact that most of them received the company from their parents gives them another responsibility and obligation in maintaining the company within the family, even when problems multiply and often the logical option was to sell or introduce new shareholders in the company [58,59,115,116].

Although most of the footwear sector companies are family members, and cumulatively small- and medium-sized enterprises (SME), the need to professionalize has been growing over time. The way companies have found to do it is through human resources, or organizational capacity. Based on the respondents’ reports, companies have become more professional through the acquisition of new machinery and process improvement to increase their productive capacity [117]. Nowadays, the recruitment of specialized staff in these companies is beginning to show itself among family businesses. They feel that to face the current market and grow, they need staff with more and better skills. The feeling of the interviewees is that today, it is not enough to produce a lot and well, it is also necessary to be competent in the search for new clients, in design and in marketing, particular areas that require staff with specific competence to perform it [88,117].

Respondents recognize that the relationship between the two subsystems—family and company—is vital, as their answers prove. It is precisely in these responses that the following sub-themes stand out within the company–family relationship: influences on financial results, management of conflicts, attitude and intergenerational involvement [88,115,118].

The influence on the financial results is mostly related to the expense that the company has with the family, be it through money that leaves the company for the personal enjoyment of the family, or through the charges that family members, within the company, represent: “some benefit from being family members” [58].

It is commonsense that a relationship creates conflict. In that relationship, we include a personal aspect (family) and a professional aspect (company). Therefore, the management of that same conflict becomes relevant in everyday life. However, this conflict is not always easy to manage, especially when it can arise between father and son, husband and wife, between brothers or between cousins, as the conflict between CEO and employee tends to be resolved quickly and surgically, and the same tendency does not apply when the conflict arises between CEO and family [115,118].

For better or worse, the family has always been the epicenter of the company’s life. With a great spirit of sacrifice and entrepreneurial spirit, this same family kept the company and made it grow. It is this attitude that allows many companies to still exist today. Paradoxically, many CEOs also claim that, at a time when the company is in a time of consolidation with many years of experience in the market, it is also the family that is holding back the evolution of the company and not raising it to the desired levels. The financial situation of most of the family members of the company is already favorable. There tends to be a more conservative attitude. This greater risk aversion does not allow the company to continue to grow, and fundamentally to remain competitive in the markets where it operates [88,115,118].

According to some interviewees, family involvement in the company, which is assumed to be intergenerational, tends not to compromise its strategic aspect. However, this is not a transversal reality for all companies. Even those that claim that the family does not compromise the company’s strategic vision tend to affirm that the family compromises the company in other dimensions, for example, the financial, which ends up, consciously or unconsciously, compromising the company’s strategy [58,88,115,118,119]. One of the moments that puts this intergenerational involvement to the test is succession, which materializes in two themes: managing expectations and adapting to new family members. The management of expectations “affects” all family elements, from the CEO to the family member who enters the company to the rest of the family who, even though they are not directly involved in the process, always have an active voice in it. Moreover, expectations management can be done at different times, the CEO who leaves and gives way to another family member, the family member who enters the company for the first time or the way the other family members face each of these moments [82,120,121].

Adapting to new family members is vitally important within the company, and adaptation will be better when fewer “loose ends” exist. FB tend to be less judgmental in hiring family members for the company, either because of the little or no training of those who enter to perform the functions proposed to them or the obligation to enter the company to serve the family legacy. Both situations require considerable adaptive gymnastics to adapt to different realities [82].

A company, whether family or not, must have consolidated management practices, and in the study carried out on family businesses in the footwear sector, management practices stand out, with issues such as knowledge sharing, innovation, leadership, barriers and the perceived benefits [59,84,122].

Knowledge sharing within FB has a central point in its favor, that is his informalism. Informalism is present within the company and passes from the administration to the remaining employees, through the relaxed family environment within the administration or between family members, where this sharing of knowledge often overflows the physical barriers of the company, and passes into the family [59,122,123,124].

According to the respondents, innovation within their companies has always existed in a more or less marked way, due even to the need for growth that they have been feeling. However, new generations’ entry represents a double benefit concerning innovation. Most new generations enter the company with a “refreshed” vision and a much greater risk propensity than the older family members, and then this risk propensity and this vision of the company have the power to impel the oldest elements of the family to follow this vision [59,123].

Suppose on one hand this entry of more members of the family can be positive. In that case, it also implies that whoever runs the company has strong leadership, not only with those who enter but also with those already in the company. As previously mentioned, relationships tend to be challenging to manage, and without strong leadership, it becomes more challenging to manage the company and particularly the family [59,122].

However, if this management is well done and the leadership is present, the perceived benefits are also clear, mainly allocating the family in the most critical positions. This can be seen in the relationship of trust and complicity with a family member, which is a responsible position that turns out to be a clear advantage [59,84,123,124].

Nevertheless, it is also in the family that those who manage FB encounter the most significant barriers, whether in pursuing their vision for the company, in the entry of new shareholders or in the company’s strategic vision [59,84,120,121,122,123,124].

Furthermore, finally, we have a family business’s performance, mainly when family members are in management. If it is true that many family businesses exist today because of the family, and everything they have given to the company, it is also true that many family businesses now face severe problems because of the family. Comfort, risk aversion, problems caused by family relationships or the entry of new generations are situations that jeopardize the continuity of the company within the family, not to mention the continuity of the company in the market where they operate, because solving these problems is not simple, and if they are not solved, the extinction of the company increasingly seems to be an inevitable path to be taken [82,124,125].

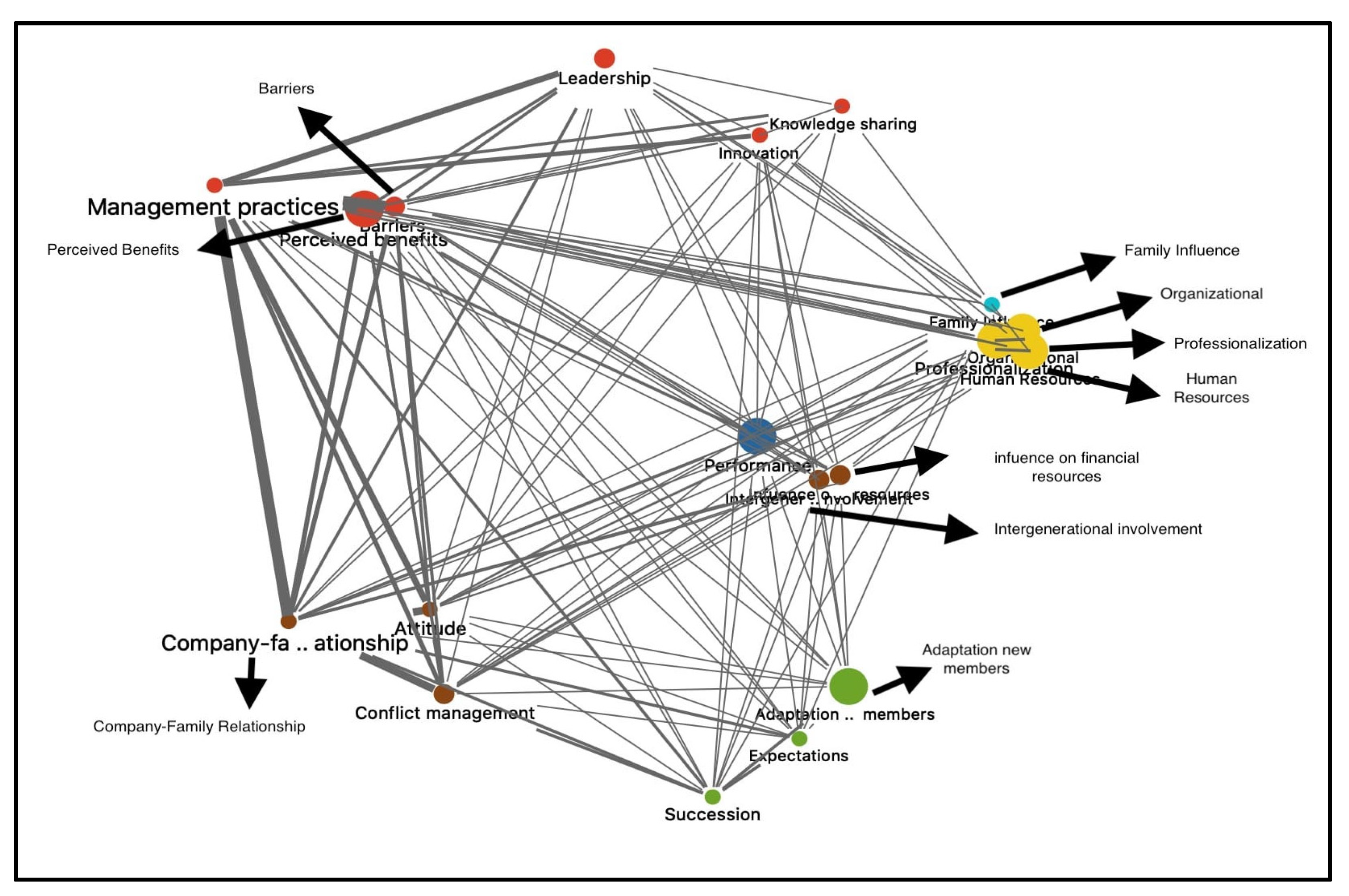

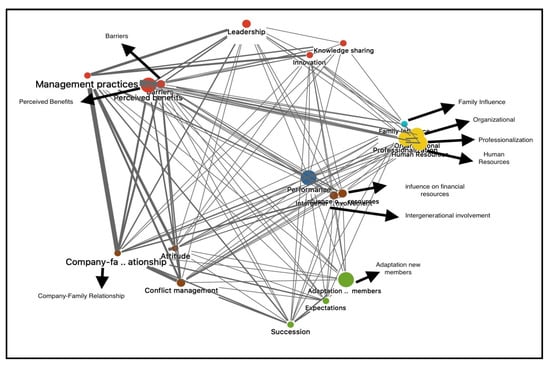

For a better understanding of the study, Figure 3 allows us to understand the relationship between emerging themes and their saturation in the interviewees’ discourse. It can be seen in this way that the main themes in the interviewees’ discourse were knowledge sharing, professionalization, family influence, performance and influence on financial results. The relationship set shows that one of the themes studied—performance—is strongly associated with the company’s professionalization, financial results and generational involvement. This link suggests the need for companies to become professional, whether through the acquisition of machinery, through process improvement or, increasingly present in companies’ reality, the need to professionalize their staff. Naturally, this need has a strong financial impact on the company, if the acquisition of machinery and process improvement implies a high financial effort. However, more or less, these investments have always been made. The truth is that investment in specialized staff has always been seen as an expense with no return in sight. However, this seems to be a changing reality for the CEO, who realizes that the family does not reach the challenges that the market demands today and that the company cannot meet. Not only does it not meet the demands of the current market, but their involvement in the company usually represents increased costs for the company, mainly because the family seldom receives due to the position they hold, but rather due to the degree of kinship they have with the owners of the company. Owners are also not “free from guilt “, since when succession to the new generations occurs, they tend to perpetuate themselves within the structure, often with associated costs, as they continue to receive the salary they received for the functions now performed by someone else.

Figure 3.

Occurrence and list of emerging themes. Source: elaborated by the authors.

The strong relationship between family influence and human resources also corroborates what was stated above, with the choice of specific human resources being common practice, and the position that they will occupy being strongly influenced by the family, whether she works for the company or not.

Likewise, we can see that one of the strongest relational triangles we obtained is what involves the company–family relationship, attitude and conflict management, which makes us understand that this relationship has a strong influence on attitude, mainly the family elements that make up the company, whether in conflict management which is naturally conditioned by the kinship relationship that may exist between CEO’s and employees, or between CEO’s and other company partners.

Finally, we highlight the strong relationship between management practices, leadership and attitude. From the participants’ perspective, leadership and attitude are critical success factors for managing a family business.

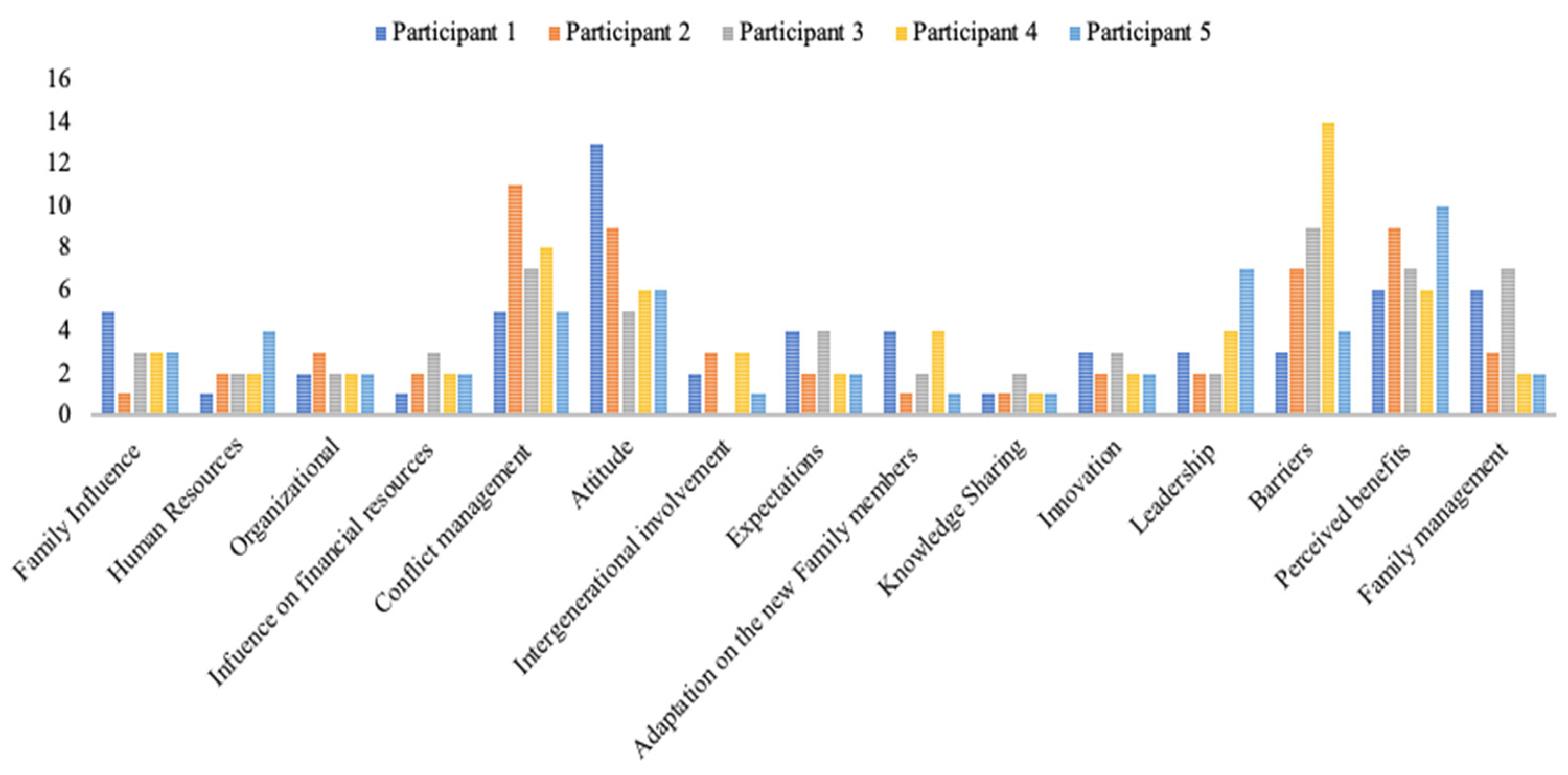

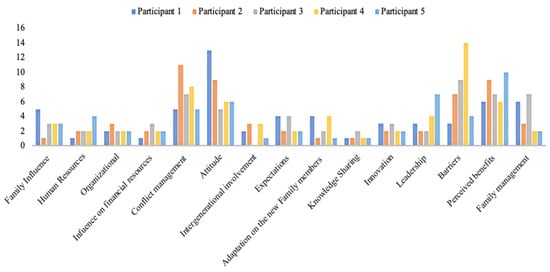

In another perspective, Figure 4 helps us understand, in a segmented way, the participants’ contribution to identifying emerging themes, based on their reports. In individual terms, it is clear that the most emerging themes were conflict management, attitude, barriers and perceived benefits.

Figure 4.

Occurrence of emerging themes. Source: elaborated by the authors.

In terms of occurrence, the categories barriers (14), attitude (13), conflict management (11) and perceived benefits (10), are evidenced by their frequency in the participants’ reports. According to these data, it appears that Participant 1 (P1), Participant 2 (P2) and Participant 4 (P4) are evidenced by the more significant number of themes and sub-themes arising from their testimonies.

Through the analysis software MAXQDA18, it was possible to build a word cloud (Figure 5) that coincides with a more superficial lexical analysis, highlighting the most influential words in the interviews’ analysis corpus. Based on the image in question, we can observe the most frequent set of words in the interviews with the participants, which are more associated with the problem under analysis, with greater emphasis on the terms: company, family, management, constraints, involvement, property, future, commitment, professionals, kinship, knowledge, work, quality, influences, risk, disadvantages, generations and succession. This output of results reflects the keywords, which reflect the collection of this problem, in the management of family businesses in the footwear industry.

Figure 5.

Word Cloud. Source: elaborated by the authors.

5. Discussion

Concerning property, we found that family influence is significant in the company’s continuity in the family. The words honor and pride stand out in the CEOs’ responses. It is practically unanimous that the fact that most of them received the company from their parents gives them another responsibility: “(…) it was my father’s and he passed it on to us and so far we have not felt the need for it to be different (…)” [115].

Concerning professionalization, two sub-themes stand out: human resources and organizational capacity, which were the primary targets for the professionalization of companies and the acquisition of machinery in order to increase productivity: “(…) in recent years, our great investment in the professionalization of the company involves the acquisition of machinery, that is, doing more with the same workforce (…) ”. In terms of human resources, it went through the recruitment of specialized staff, to leverage the company to levels where it has not yet been, whether it was in design, looking for new customers, or in its financial management: “(…) we felt the need to hire 2/3 experienced professionals to embrace new markets and grow in terms of production (…)” [117].

Respondents recognized that the relationship between the two subsystems—family and company—is of vital importance, from which the following sub-themes stood out: influences on financial results, conflict management, attitude and intergenerational involvement. The influence on financial results is mostly related to the company’s expense, whether through money that leaves the company for the personal enjoyment of the family or through the charges that family members within the company represent: “some benefit from being in the family”. The conflict marks the day-to-day of these companies. Their management is not always easy to do, especially when it can arise between father and son, husband and wife, between brothers or between cousins, because the conflict between CEO and employee tends to be resolved quickly and surgically. The same tendency does not apply when the conflict arises between CEO and family, “(…) we had a family member that ended in dismissal, but that was resolved to ensure the well-being in the company (…)”.

The attitude was strongly emphasized in the responses given by the respondents, where on the one hand, the entrepreneurial and selfless attitude was useful at the beginning of the company, and on the other hand, the financial situation of most of the family members who are part of the company is already favorable, supporting consolidation of the company in the market, which leads to a more conservative attitude and a greater aversion to risk, which does not allow the company to continue to grow, and fundamentally, to remain competitive in the markets where it operates “(…) In general family businesses, there is some reluctance to let people outside the family enter the company’s capital. Often, family members adapt to the reality in which the company is at the moment and create obstacles to its growth (…)”.

According to some interviewees, family involvement in the company, which presupposes intergenerational involvement, tends not to compromise its strategic aspect. However, this is not a reality across all companies. The idea that the family does not always compromise the strategic vision of the company does not invalidate that this situation does not occur at the financial level: “(…) the family does not influence us in our strategic decision for the future of the company (…) decisions are still made, due to the great aversion that the family may have to these decisions risk. The important thing here is always the company (…)” [118].

Concerning succession, when it happens in companies, it marks their lives and materializes into two major sub-themes, managing expectations and adapting to new family members. The management of expectations “affects” all family elements, from the CEO, to the family member who enters the company, to the rest of the family, who, although not directly involved in the process, always have an active voice in it. Getting all the family members to be in sync in this delicate moment is one of the most significant difficulties for the company in this process: “(…) I do not think it is the entry of new generations that can be harmful to the company, it does not take care of the future now, which may one day cause the company to stop working (…)”. However, adapting to new family members is also vitally important, to ensure a peaceful transition, but also for daily living within the company, as these companies tend to be less judgmental in hiring family members, whether for little or no training of those who enter to perform the functions that are proposed, either by the obligation to enter the company to serve the family legacy. Among the respondents, we have both realities, as the following statement proves, “(…) the entry of new generations was peaceful, and we did not feel the lack of desire to work (…)” [82].

Whether family or not, a company must have consolidated management practices. In the study carried out on family companies in the footwear industry, management practices highlight issues such as knowledge sharing, innovation, leadership, barriers and the perceived benefits. Concerning knowledge sharing, FB has a central point in their favor, their informalism. Informalism is present within the company and passes from the administration to the remaining employees, through the family atmosphere, and is often relaxed even within the administration or among family members, where this sharing of knowledge often overflows the physical barriers of the company. It passes to the family bosom: “(…) one of the great advantages of family businesses, I think, is knowledge passes from parents to children, and even within the company the sharing of knowledge between everyone is the greatest result of the family environment (…)”. About innovation, respondents state that innovation within their companies has always existed in a more or less pronounced way, even due to the need for growth that they have been feeling. However, the entry of new generations configures a double benefit concerning innovation, mainly due to its risk propensity that impels the older generations not to settle: “(…) the younger ones come with another vision of the company and like to take more risks, and then because they do not allow us to accommodate and lead us to be more proactive in terms of innovation (…)”. If the entry of more family members can be considered positive, this implies that this leadership is reinforced by those who enter and by those who were already in the company: “(…) I have never had difficulty in giving orders to any family member who works at the company, I often feel that I have a greater demand for them than for the other workers (…)”. The perceived benefits are clear within these companies, mainly allocating the family to the most critical positions. This is perceived by the relationship of trust and complicity that one has with a family member, which is a responsible position that turns out to be a clear advantage: “(…) concerning the advantages, one of them is having the family members in the right positions, in places where we need someone to trust, who in our case in almost all middle management positions are family members who occupy them (…)”. However, it is also in the family that respondents encounter the most significant barriers, whether in pursuing their vision for the company, in the entry of new shareholders or in the company’s strategic vision: “(…) it is difficult to reconcile the family’s opinions, adding a new shareholder to it can make everything even more complicated (…)” [84].

Moreover, finally, we studied the performance of a family business, and mainly when family members are in management. If it is true that many of the family businesses exist today because of the family, due to everything they have given to the company, it is also true that many family businesses now face severe problems because of the family: “(…) I have the perception that the family influences productivity and in this case, it is not positive. Moreover, due to the dimension that the company already has, I think it is no longer justified for it to be familiar (…)” [124].

In short, it can be seen from the answers given by the interviewees that all the topics addressed are present in the company they manage, or at least in their awareness, as they may be a problem or a solution for the company. It was also clear that their knowledge of family business management’s reality is efficient and comes from everyday life and not from a theoretical component or based on theoretical assumptions.

6. Conclusions

This research work’s general objective was to understand the reality of the management of family businesses in the footwear industry through the vision of the CEOs of five companies that accepted to be the object of this case study. After an extensive literature review on this area of knowledge, it was decided to study six transversal themes of family businesses: property, professionalization, the company–family relationship, succession, management practices and performance.

This article makes it possible to contribute to the evolution of the literature related to this area of knowledge, inherent to the management of family businesses and performance, insofar as the results allowed a greater understanding regarding those that are the main concerns of the CEOs of this type of companies, namely concerning issues related to property, professionalization, company–family relationship, succession, management and performance practices. It was also possible to discover, within each central theme, the subthemes (family influence, human resources, organizational capacity, influence on financial results, conflict management, attitude, intergenerational involvement, expectations, adaptation to new family members, knowledge sharing, innovation, leadership, barriers, perceived benefits and management by family members) and the relationship between them.

Based on the predicted objectives and the results achieved, the research design stands out as the main limitation of this work. Although the case study method’s choice provides exhaustive and specific information about the phenomenon under analysis, its results and conclusions cannot be generalized. This is compounded by the fact that the knowledge acquired is restricted to only five cases. In the future, in new research, multiple cases should be considered in several companies across the country, to allow a comparative study that can be generalized.

Future studies should try to overcome these limitations and explore and understand other themes that have been discussed in the literature review and that were not the target of this study. In subsequent investigations, it is suggested to analyze more family companies in the footwear business in other economic and cultural contexts to confirm, improve and adapt this case study’s results. The insights obtained must be tested in quantitative approaches and allow to outline new flows for future investigations.

These findings and conclusions are expected to contribute to a better understanding of this issue, the management of family businesses and their succession, as a phenomenon of great economic and social importance. It is considered that this theme is a fertile field for future investigations, as the study of the problem of family businesses applied to education still has a long way to go in order to become increasingly effective and scientifically robust.

To conclude, it is considered that family businesses, particularly those that have been consulted, should awaken to a greater interest in the issue of family business management to provide themselves with greater and better information to face obstacles and enhance the benefits.

From a global perspective, it is concluded that the research adequately integrated and interconnected the various theoretical frameworks.

This article presented several contributions inherent to the problems related to family businesses and their forms of management. Throughout the elaboration of this research work, we have tried to develop a study that analyzes family businesses’ main characteristics and their impact on performance. We started by analyzing the existing literature in this area, understanding its current development status and respective organization of this knowledge area for this better understanding.

The systematic review of the literature allowed us to identify that this subject is increasingly studied. However, it was not necessary to continue the path undertaken until then, and it is necessary that other researchers in the area can, in the future, extrapolate this study to other companies, improving it, in order to test its effectiveness and application in this area of knowledge. Concerning the results of the qualitative case study, it was possible to conclude that there is a need to continue studying this area of knowledge to understand, with increasing robustness, the challenges inherent to this type of companies and their management. It was possible to contribute to the evolution of knowledge in this area of science by understanding the CEOs of family businesses’ main concerns regarding management and detection of the leading research topics on family businesses and performance. It was also possible to contribute to the empirical analysis, through interviews, of the CEO’s opinion on fundamental themes such as ownership, professionalization, employment–family relations, succession, management practices and performance. It was also possible to identify emerging themes and sub-themes in this research area and their relationship. Finally, it was also demonstrated that these organizations contribute strongly to the country’s economic and social development.

7. Limitations and Suggestions for Future Research

However rigorous and applied, any research study faces two types of limitations: those resulting from the choices made by the researcher throughout the research process, and those which, while unintended, are the result of aspects that the researcher cannot control.

Concerning the systematic review of the literature, we can highlight that research was limited to a Web of Science database, a conditioning characteristic of research. Another conditioning factor is the research expressions “Family Business Management and Performance” and “Family Firm Management and Performance” applied in the Web of Science. However, this type of methodology is liable to be questioned, since the use of only, and concretely, these two search expressions was an option that may not be the agreement of all, claiming that instead of the choice of these expressions, if others were used, we could withdraw another type of results and therefore another type of final output. However, the terms used were tested several times, using other keywords, and where the results obtained strengthened the choice in relation to them, which gave a larger output and thematic scope. The qualitative case study relating to the reality of the footwear industry is not without its limitations. The most obvious limitations have to do with research design. Although the case study method’s choice provides exhaustive and specific information on the phenomenon without analysis, its results and conclusions cannot be generalized. This is compounded by the fact that the knowledge acquired is limited to only five cases. There is still a need to analyze more family shoe companies in other economic and cultural contexts to confirm, improve and adapt this case study’s results. The knowledge gained should be tested on quantitative approaches and allow new future research flows to be outlined. Another limitation is related to the sample size.

For future research proposals, it is suggested that other analyses be made of the existing literature, using this same methodology, but in the meantime, using other keywords, both in the database used here, and guided by others, to allow consolidation of all of the knowledge produced so far on the subject. In the future, in new research, multiple cases should be considered in several companies across the country, to allow a comparative study that can be generalized. Finally, it is hoped that these findings and conclusions will contribute to a better understanding of family business management, and its succession, as a phenomenon of great economic and social importance. It is considered that this theme is a fertile field for future investigations, as the study of the problem of family businesses still has a long way to go, in the sense of becoming increasingly useful and scientifically robust.

We are convinced that the indications set out here could be important indicators for carrying out breakthrough research that will allow further reflection on this area of knowledge and contributions to the development of the body of literature related to family business management.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.Q., A.C., N.S. and R.S.; methodology, R.S. and N.S.; software, R.S. and N.S.; validation, A.C., P.Q. and R.S.; formal analysis, N.S. and R.S.; investigation, A.C., R.S., P.Q. and N.S.; writing—original draft preparation, A.C. and R.S.; writing—review and editing, A.C., P.Q. and R.S.; visualization, R.S.; supervision, R.S. and A.C.; project administration, A.C. and R.S.; funding acquisition, P.Q. and R.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

National funds support the author Rui Silva’s work through the FCT—Portuguese Foundation for Science and Technology under the project UIDB/04011/2020. The work of the author Patrícia Quesado is financed by national funds through FCT—Foundation for Science and Technology, I.P., within the scope of multi-annual funding UIDB/04043/2020.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the Polytechnic Institute of Cávado and Ave (School of Management) and CICF (Research Centre on Accounting and Taxation), and University of Trás-os-Montes e Alto Douro and CETRAD (Centre for Transdisciplinary Development Studies).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

CEO’s Interview Guide.

Table A1.

CEO’s Interview Guide.

| Propositions | Literature |

|---|---|

Performance:

| Bennedsen et al. [82]; Le Breton-Miller and Miller [125]; Minichilli et al. [124]. |

Management Practices:

| Bloom and Van Reenen [84]; Brunninge et al. [123]; Gomez–Mejia et al. [122]; Minichilli et al. [124]; Morris et al. [120]; Villalonga and Amit [59]. |

Succession:

| Bennedsen et al. [82]; Morris et al. [120]; Perez-Gonzalez [121]. |

Company–Family Interrelationship:

| Anderson and Reeb [58]; Kellermanns and Eddleston [119]; McConaughy et al. [88]; Sciascia and Mazzola [115]; Sirmon et al. [118]. |

Professionalization:

| Ali et al. [117]; McConaughy et al. [88]. |

Property:

| Anderson and Reeb [58]; Sciascia and Mazzola [115]; Villalonga and Amit [59]; Westhead and Howorth [116]. |

References

- Lea, J.W. Keeping it in the Family: Successful Succession of the Family Business; Wiley: Hoboken, NY, UAS, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Lodi, J.B. Sucessão e Conflito na Empresa Familiar; Livraria Pioneira Editora: Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 1897. [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira, M.M. A troca de comando. Peq. Emp. Gran Neg. 1993, 4, 19–25. [Google Scholar]

- Rock, S. Empresas Familiares-Um Guia Para a Sua Gestão; Mem Martins: Lisboa, Portugal, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Poza, E.J.; Daugherty, M.S. Family Business; Cengage Learning: Boston, MA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Zellweger, T. Managing the Family Business: Theory and Practice; Edward Elgar Publishing: Northampton, MA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Europea, C. Overview of Family-Business-Relevant Issues: Research, Networks, Policy Measures and Existing Studies; European Commission—Enterprise and Industry Directorate-General: Brussels, Belgium, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Litz, R.A. The family business: Toward definitional clarity. Fam. Bus. Rev. 1995, 8, 71–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gersick, K.E.; Davis, J.A.; Hampton, M.M.; Lansberg, I. Generation to Generation, Life Cycles of the Family Business; Harvard Business School Press: Boston, MA, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Almeida, H.; Park, S.Y.; Subrahmanyam, M.G.; Wolfenzon, D. The structure and formation of business groups: Evidence from Korean chaebols. J. Fin. Econ. 2011, 99, 447–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oudah, M.; Jabeen, F.; Dixon, C. Determinants linked to family business sustainability in the UAE: An AHP approach. Sustainability 2018, 10, 246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- APICCAPS. APICCAPS Facts and Numbers 2019; APICCAPS—Portuguese Footwear, Components, Leather Goods Manufacturers’ Association: Porto, Portugal, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Cano-Rubio, M.; Fuentes-Lombardo, G.; Vallejo-Martos, M.C. Influence of the lack of a standard definition of “family business” on research into their international strategies. Eur. Res. Manag. Bus. Econ. 2017, 23, 132–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pamplona, E.; Magro, C.D.; Silva, T.D. Estrutura de capital e desempenho econômico de empresas familiares do Brasil e de Portugal. Rev. Gest. Países Líng. Port. 2017, 16, 38–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petticrew, M.; Roberts, H. Systematic reviews–do they ‘work’ in informing decision-making around health inequalities? Health Econ. Policy Law 2008, 3, 197–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Denyer, D.; Tranfield, D. Producing a systematic review. In The Sage Handbook of Organizational Research Methods; Buchanan, D., Bryman, A., Eds.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2009; pp. 671–689. [Google Scholar]

- Sampaio, R.; Mancini, M. Estudos de Revisão Sistemática: Um Guia para Síntese Criteriosa da Evidência Científica. Rev. Bras. Fisiot. 2007, 11, 83–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, S. Writing a Review Article: For the Beginners in Research. Int. J. Sci. Res. 2014, 3, 813–815. [Google Scholar]

- Gil, A. Como Elaborar Projetos de Pesquisa; Atlas: São Paulo, Brazil, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Markoni, M.; Lakatos, E. Metodologia do Trabalho Científico: Procedimentos Básicos, Pesquisa Bibliográfica, Projeto e Relatório, Publicações e Trabalhos Científicos; Atlas: São Paulo, Brazil, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Martins, G.; Theóphilo, C. Metodologia da Investigação Para Ciências Sociais Aplicadas; Atlas: São Paulo, Brazil, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Petticrew, M.; Roberts, H. Systematic Reviews in the Social Sciences-a Practical Guide; Blackwell Publishing: Oxford, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Lozano-Reina, G.; Sánchez-Marín, G. Say on pay and executive compensation: A systematic review and suggestions for developing the field. Hum. Res. Manag. Rev. 2020, 30, 100683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vergara, S. Projetos e Relatórios de Pesquisa em Administração; Atlas: São Paulo, Brazil, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Nolan, C.T.; Garavan, T.N. Human resource development in SMEs: A systematic review of the literature. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2016, 18, 85–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Short, J. The Art of Writing a Review Article. J. Manag. 2009, 35, 1312–1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, G. Manual Para Elaboração de Monografias e Dissertações; Atlas: São Paulo, Brazil, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Tranfield, D.; Denyer, D.; Smart, P. Towards a Methodology for Developing Evidence-Informed Management Knowledge by Means of Systematic Review. Brit. J. Manag. 2003, 14, 207–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, M.; Toledo, J. Análise dos modelos e atividades do pré-desenvolvimento: Revisão bibliográfica sistemática. Gest. Prod. 2016, 23, 704–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leone, N. A dimensão fisica das pequenas e médias empresas (PME’S): À procura de um critério homogeneizador. Rev. Adm. Emp. 1991, 31, 53–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luan, C.-J.; Chen, Y.-Y.; Huang, H.-Y.; Wang, K.-S. CEO succession decision in family businesses-A corporate governance perspective. Asia Pac. Manag. Rev. 2018, 23, 130–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, P.; Chrisman, J.J.; Chua, J.H. Strategic management of the family business: Past research and future challenges. Fam. Bus. Rev. 1997, 10, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, J.L. The special role of strategic planning for family businesses. Fam. Bus. Rev. 1988, 1, 105–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohn, M. Passing the Torch: Succession, Retirement, and Estate Planning in Family-Owned Businesses; McGraw-Hill Companies: New York, NY, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Álvares, E. Governando a Empresa Familiar; Qualitymark Editora Ltda: Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Lodi, J.B. A ética na Empresa Familiar; Livraria Pioneira Editora: Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Astrachan, J.H.; Klein, S.B.; Smyrnios, K.X. The F-PEC scale of family influence: A proposal for solving the family business definition problem. Fam. Bus. Rev. 2002, 15, 45–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miralles-Marcelo, J.L.; del Mar Miralles-Quirós, M.; Lisboa, I. The impact of family control on firm performance: Evidence from Portugal and Spain. J. Fam. Bus. Strategy 2014, 5, 156–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pindado, J.; Requejo, I. Family business performance from a governance perspective: A review of empirical research. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2015, 17, 279–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]