Testing the Effectiveness of CSR Dimensions for Small Business Entrepreneurs

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. The Coherence of Legitimacy Theory and Social Responsibility

“… a condition or status which exists when an entity’s value system is congruent with the value system of the more extensive social system of which the entity is a part. When a disparity, actual or potential, exists between the two value systems, there is a threat to the entity’s legitimacy.”

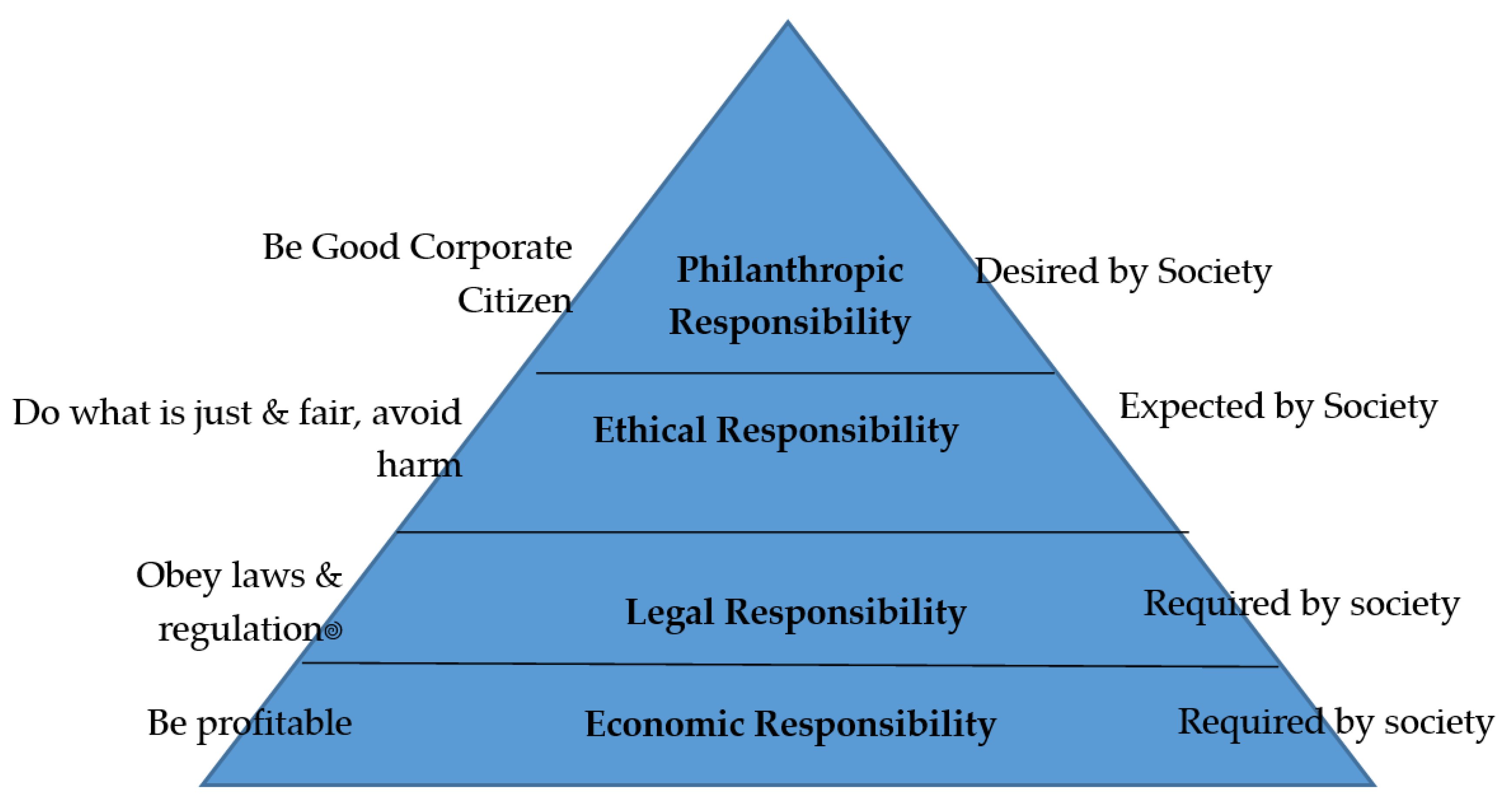

2.2. Dimensional Social Responsibility

3. Research Scope and Methods

3.1. Data Collection and Respondents

3.2. Variable Operational Techniques of Data Analysis

4. Analysis and Discussion

4.1. Low-Cost Revolving Fund Assistance for SMEs

4.2. Equipment Assistance for SMEs

4.3. SMEs Assistance

4.4. Marketing Assistance for SMEs

4.5. Ease and Simplification of Credit Requirements for SMEs

4.6. Education and Training for SMEs

4.7. Low-Cost Accessibility for SMEs

4.8. Involvement of External Parties for Empowering SMEs

4.9. Empirical Dimensions of CSR

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bernardi, C.; Stark, A.W. Environmental, social and governance disclosure, integrated, and the accuracy of analyst forecast. Br. Account. Rev. 2018, 50, 16–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Amalia, F.A.; Suprapti, E. Does the High or Low of Corporate Social Responsibility Disclosure Affect Tax Avoidance? J. Account. Invest. 2020, 21, 277–288. Available online: https://borang.umy.ac.id/index.php/ai/article/view/7655 (accessed on 15 July 2020). [CrossRef]

- Belkaoui, A.; Karpik, P.G. Determinants of the corporate decision to disclose social information. Account. Audit. Account. J. 1989, 2, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdianty, R.W.; Bintoro, I. Pengaruh Kinerja Keuangan Terhadap Nilai Perusahaan Dengan Corporate Social Responsibility dan Good Corporate Governance sebagai Variabel Pemoderasi (Studi Pada Perusahan Manufaktur yang Terdaftar di Bursa Efek Indonesia Periode 2010—2014). J. Manaj. Bisnis 2015, 6, 376–396. [Google Scholar]

- Junaidi, J. Analisis pengungkapan CSR perbankan syariah di Indonesia berdasarkan islamic social reporting index. J. Account. Invest. 2015, 16, 7585. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, L.M. Study of Internal Corporate Social Responsibility practice in Small Medium Entreprises Located in the State of Selangor. Res. Humanit. Soc. Sci. 2015, 5, 14–36. [Google Scholar]

- García-Sánchez, I.-M.; García-Sánchez, A. Corporate Social Responsibility during COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2020, 6, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devi, J.T.; Hemant, K. Corporate Social Responsibility Perspectives of Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs)—A Case Study of Mauritius. Adv. Manag. 2009, 2, 44–53. [Google Scholar]

- Hadi, N. Social Responsibility; Graha Ilmu: Yogyakarta, Indonesia, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Hadi, N.; Mariana, E. Measuring social responsibility for employee with NH Approach Methode. Iqtishodia J. 2018, 11, 243–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamali, D.; Zanhour, M.; Keshishian, T. Peculiar strengths and relational attributes of SMEs in context of CSR. J. Bus. Ethics 2008, 87, 355–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morsing, M.; Perrini, F. CSR in SMEs: Do SMEs matter for the CSR agenda? Bus. Ethics Eur. Rev. 2009, 18, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murillo, D.; Lozano, J. SMEs and CSR: An approach to CSR in their own words. J. Bus. Ethics 2006, 67, 227–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spence, L.J. CSR and small business in a European policy context: The five “C”s of CSR and small business research agenda 2007. Bus. Soc. Rev. 2007, 112, 533–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suprapto, S.A.A. Pola Tanggung Jawab Sosial Perusahaan Lokal di Jakarta. J. Filantr. dan Masy. Madani GALANG 2006, 1. Available online: https://catalogue.paramadina.ac.id/index.php?p=show_detail&id=8470 (accessed on 23 May 2020).

- Wicaksono, A.S.; Ariyani, W. Model Pemberdayaan Usaha Mikro Kecil Dan Menengah (Umkm) Melalui Program Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) Pada Industri Rokok Di Kudus. J. Sos. Budaya 2013, 6, 29–39. [Google Scholar]

- Deegan, C. The Legitimizing Effect of Social and Environmental Disclosures—A Theoretical Foundation. Account. Audit. Account. J. 2002, 15, 282–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wibisono, Y. Membedah Konsep dan Aplikasi Corporate Social Responsibility (Exploring Applied & Concept of Corporate Social Responsibility); Fascho Publishing: Jakarta, Indonesia, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, M.; Narjoud, S.; Granata, J. When collective action drives corporate social responsibility implementation in small and medium-sized enterprises: The case of a network of French winemaking cooperatives. Int. J. Entrep. Small Bus. 2017, 32, 7–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdirahman, Z.-Z.; Sauvee, L.; Shiri, G. Analyzing networks effects of corporate social responsibility implementation in food small and medium enterprises. J. Chain Netw. Sci. 2014, 14, 103–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fadun, S.O. Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) Practices and Stakeholders Expectations: The Nigerian Perspectives. Res. Bus. Manag. 2014, 1, 13–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jenkins, H. Business opportunity’ model of corporate social responsibility for small- and medium-sized enterprises. Bus. Ethics Eur. Rev. 2009, 18, 21–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karen, D.C.; Linh, C.V. Impact of CSR on SMEs: The case of global performance in France. Int. Bus. Res. 2012, 5, 50–55. [Google Scholar]

- Khanifah, K.; Udin, U.; Hadi, N.; Alfiana, F. Environmental performance and firm value: Testing the role of firm reputation in emerging countries. Int. J. Ene. Econ. Pol. 2020, 10, 96–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadi, H.; Khanifah, N.H. Approach: Social responsibility performance measuring case of mining Industries in Indonesia Stock Exchange. In Proceedings of the 3rd Annual Seminar and Conference on Global Issue, Semarang, Indonesia, 16–17 November 2017; pp. 189–191. [Google Scholar]

- Spence, L.J.; Rutherfoord, R. Small Business and Empirical Perspectives in Business Ethics: Editorial. J. Bus. Ethics 2003, 47, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tilling, M.V.; Tilt, C.A. The edge of Legitimacy: Voluntary Social and Environmental Reporting in Rothman’s 1956–1999 Annual Report. Account. Audit. Account. J. 2010, 23, 55–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Villiers, C.; Maroun, W. Introduction do sustainability accounting and integrated reporting. Sustain. Account. Integr. Report. 2018, 1, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Haniffa, R.; Cooke, T.E. The impact of culture and governance on corporate social reporting. J. Account. Public Policy 2005, 24, 391–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mousa, G.; Hassan, N.T. Legitimacy theory and environmental practices: Short Notre. Int. J. Bus. Stat. Anal. 2015, 2, 41–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Donovan, G. Environmental Disclosures in the Annual Report: Extending the Applicability and Predictive Power of Legitimacy Theory. Account. Audit. Account. J. 2002, 15, 344–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mobus, J.L. Mandatory Environmental Disclosure in a Legitimacy Theory Context. Account. Audit. Account. J. 2005, 21, 492–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deegan, C.; Rankin, M.; Voght, P. Firms’ Disclosure Reactions to Social Incidents: Australian Evidence. Account. Forum 2000, 24, 101–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suchman, M. Managing Legitimacy: Strategic and Institutional Approach. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1995, 20, 571–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dowling, J.; Pfeffer, J. Organizational legitimacy: Social values and organizational behavior. Pac. Sociol. Rev. 1975, 18, 122–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cormier, D.; Gordon, I.M. An Examination of Social and Environmental Reporting Strategies. Account. Audit. Account. J. 2001, 14, 587–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, I.A.; Crane, A. Corporate social responsibility in small and medium-sized enterprises: Investigating employee engagement in fair trade companies. Eur. Rev. 2010, 19, 126–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Donovan, G. Managing legitimacy through increased corporate environmental reporting: An exploratory study. Interdiscip. Environ. Rev. 1999, 1, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfeffer, J.; Salancik, G. The External Control. of Organizations: A Resource Dependence Perspective; Harper and Row: New York, NY, USA, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Herrera, J.; Heras-Rosas, C.D.L. Economic, Non-Economic and Critical Factors for the Sustainability of Family Firms. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2020, 6, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.-H.; Jung, S.-H. Study on CEO characteristics for management of public art performance centers. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2015, 1, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Deegan, C.; Rankin, M.; Tobin, J. An Examination of the Corporate Social and Environmental Disclosures of BHP from 1983–1997: A Test of Legitimacy Theory. Account. Audit. Account. J. 2002, 15, 312–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowen, E. The Influence of Meteoritic Dust on Rainfall. Aust. J. Phys. 1953, 6, 490–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, A.B. Carroll’s pyramid of CSR: Taking another look. Int. J. Corp. Soc. Responsib. 2016, 1, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hammann, E.-M.; Habisch, A.; Pechlaner, H. Values that create value: Socially responsible business practices in SMEs-empirical evidence from German companies. Bus. Ethics Eur. Rev. 2008, 18, 37–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkins, H. Small business champions for corporate social responsibility. J. Bus. Ethics 2006, 67, 241–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorondutse, A.H.; Hilman, H. Business Social Responsibility (BSR) and Small and Medium Enterprises (SME) Relations: Evidence from Nigerian Perspectives. Int. J. Manag. Res. Rev. 2013, 3, 2346. [Google Scholar]

- Perrini, F.; Russo, A.; Tencati, A. CSR strategies of SMEs and large firms: Evidence from Italy. J. Bus. Ethics 2007, 74, 285–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herbohn, K.; Walker, J.; Loo, H.Y.M. Corporate social responsibility: The link between sustainability disclosure and sustainability performance. Abacus 2014, 50, 422–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inyang, B.J. Defining the Role Engagement of Small and Medium-Size Enterprises (SMEs) in Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR). Int. Bus. Res. 2013, 6, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, D.J. Corporate social responsibility revisited. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1991, 16, 691–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Carroll, A.B. Corporate social responsibility: The centerpiece of competing and complementary frameworks. Organ. Dyn. 2015, 44, 87–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obalola, M. Beyond philanthropy: Corporate social responsibility in Nigerian insurance industry. Soc. Responsib. J. 2008, 4, 538–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madden, K.; Scaife, W.; Crissman, K. How and why small to medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) engage with their communities: An Australian study. Int. J. Nonprofit Volunt. Sect. Mark. 2006, 11, 49–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Carroll, A.B. The pyramid of corporate social responsibility: Toward the moral management of organizational stakeholders. Bus. Horizons 1991, 34, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lepoutre, J.; Heene, A. Investigating the impact of firm size on small business social responsibility: A critical review. J. Bus. Ethics 2006, 67, 257–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Fong, M. The corporate social responsibility orientation of Chinese small and medium enterprises. J. Bus. Syst. Gov. Ethics 2010, 5, 33–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| No | Variable | Dimension of CSR |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Revolving fund | (1) Low Interest (Q1); (2) Soft returns (Q2); (3) Long maturity (Q3). |

| 2 | Equipment | (1) Assistance with production equipment (Q4); (2) Production system assistance (Q5); (3) Delivery system assistance (Q6). |

| 3 | Assistance | (1) Marketing assistance (Q7); (2) Production assistance (Q8); (3) Bookkeeping assistance (Q9); (4) Tax assistance (Q10); (5) Business license assistance (Q11). |

| 5 | Marketing | (1) Product exhibition (Q12); (2) Joint promotion (Q13); (3) Gallery helm (Q14); (4) Marketing and distribution incentives (Q15). |

| 6 | Requirements | (1) Fast credit process (Q16); (2) Mild requirements (Q17); (3) Easy/uncomplicated process (Q18); (4) Simple procedure (Q19). |

| 7 | Education and Training | (1) Marketing Training (Q20); (2) Production Training (Q21); (3) Distribution Training (Q22); (4) Bookkeeping and accounting Training (Q23); (5) Employment Training (Q24). |

| 8 | Accessibility | (1) Give all parties the opportunity (Q25); (2) Applies fairly to all parties (Q26); (3) There are no exceptions (Q27); (4) Does not apply zone (Q28); (5) Easy information (Q29); (6) There are no restrictions on the type of business (Q30). |

| 9 | Involvement | (1) Cooperate with universities (Q31); (2) Collaborating with NGOs (Q32); (3) In collaboration with local leaders (Q33); (4) Collaborating with professional organizations (Q34); (5) In collaboration with local governance (Q35). |

| N | Minimum | Maximum | Mean | Std. Deviation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Revolving fund | 92 | 55.95 | 229.37 | 61.5132 | 17.78508 |

| Equipment Assistance | 92 | 55.00 | 61.34 | 57.9647 | 1.54317 |

| Accompaniment | 92 | 53.93 | 62.07 | 58.0409 | 1.77467 |

| Marketing | 92 | 54.29 | 63.13 | 58.5690 | 1.95138 |

| Requirements (Bank Cable) | 92 | 54.60 | 181.73 | 59.7048 | 12.97244 |

| Education and Training | 92 | 55.62 | 62.25 | 58.9369 | 1.45671 |

| Accessibility of Grants | 92 | 55.75 | 142.86 | 59.5859 | 8.88923 |

| Involvement of External Parties | 92 | 54.37 | 159.59 | 60.8672 | 14.69916 |

| Dimension | KMO | BTS Sig. | Dimension/ Dropped Factors | %Var. Eigenvalues | Dimension/Success Factors | Level of Effectiveness |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Revolving fund Equipment | 0.473 | 0.857 | - | 1: 35.11 | 1: Q2, Q1 | 70.16 |

| 2: 35.05 | 2: Q3 | |||||

| Accompaniment Marketing | 0.449 | 0.186 | - | 1: 39.38 | 1: Q4, Q6 | 74.93 |

| 2: 35.55 | 2: Q5 | |||||

| Credit Terms | 0.585 | 0.034 | Q10 | 1: 36.69 | 1: Q7, Q9, Q11, Q8 | 36.69 |

| education and training | 0.559 | 0.000 | Q15 | 1: 50.71 | 1: Q14, Q12, Q13 | 50.71 |

| Accessibility | 0.500 | 0.879 | Q18 | 1: 36.22 | 1: Q17, Q16 | 69.55 |

| 2: 33.33 | 2: Q19 | |||||

| Revolving fund | 0.510 | 0.678 | Q22, Q24 | 1: 37.96 | 1: Q23, Q20, Q21 | 5.23 |

| Equipment Accompaniment | 0.550 | 0.572 | Q30 | 1: 27.27 | 1: Q26, Q29, Q27 | 74.48 |

| 2: 20.21 | 2: Q28, Q25 | |||||

| Marketing | 0.562 | 0.204 | Q34, Q33 | 1: 42.34 | 1: Q35, Q31, Q32 | 42.34 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hadi, N.; Udin, U. Testing the Effectiveness of CSR Dimensions for Small Business Entrepreneurs. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2021, 7, 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/joitmc7010006

Hadi N, Udin U. Testing the Effectiveness of CSR Dimensions for Small Business Entrepreneurs. Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity. 2021; 7(1):6. https://doi.org/10.3390/joitmc7010006

Chicago/Turabian StyleHadi, Nor, and Udin Udin. 2021. "Testing the Effectiveness of CSR Dimensions for Small Business Entrepreneurs" Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity 7, no. 1: 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/joitmc7010006