Sensing Technologies, Roles and Technology Adoption Strategies for Digital Transformation of Grape Harvesting in SME Wineries

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- RQ1:

- What is the current state of the grape harvesting process among networked SMEs in a low-tech wine industry, regarding technologies used as well as work roles involved?

- RQ2:

- What are possible digital transformation pathways of networked SMEs on the example of grape harvesting for wine production?

2. Literature Review

2.1. Work in the Age of Digital Transformation

2.2. Technology Adoption Strategies in SMEs

2.3. Networked Innovation in SMEs

3. Methodology

4. Results

4.1. Technologies Deployed

4.2. Roles Involved

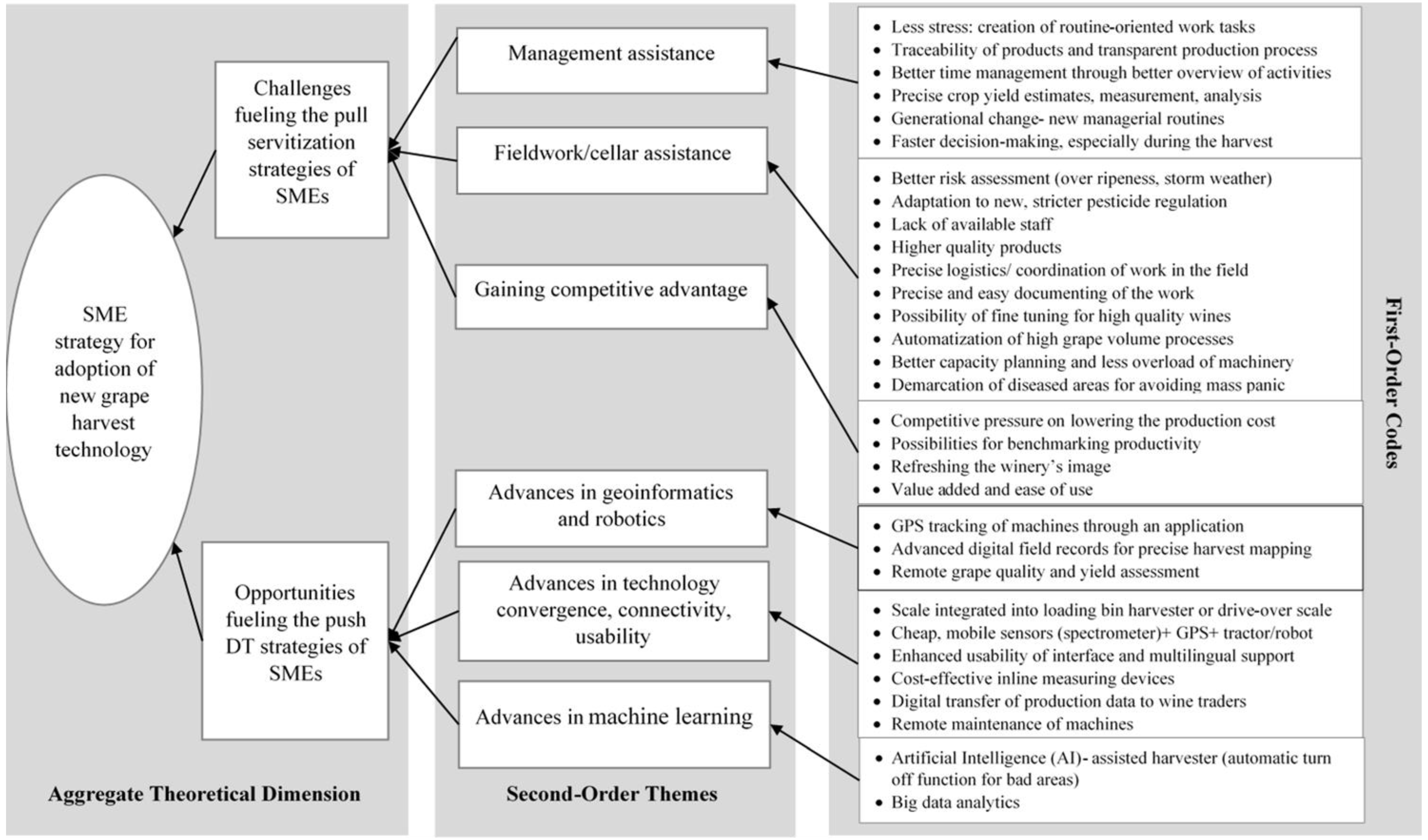

4.3. Servitization Needs, Acting as Pull Factors

4.4. New Technologies Acting as Push Factors

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| First-Order Codes | Description of the Challenge | Motivation for Overcoming the Challenge | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Management assistance | Less stress: creation of routine-oriented work tasks | The work of a wine manager/entrepreneur is highly stressful and includes often long hours | Any tool promoting work task routinization can help in reducing stress-levels induced by the unstructured nature of the production process. |

| Traceability of products and transparent production process | Traceability is being more and more demanded by certification bodies, but also consumers and new digital technologies can help these efforts | Better quality products and more direct risk management, better management options in a crisis situation of having to trace back production steps after a recall | |

| Better time management through better overview of activities | The work of a wine manager/entrepreneur is highly unpredictable and therefore stressful. | Any tool promoting real-time data tracking can help retain control over production process, while reducing stress-levels induced by a lack of data. | |

| Precise crop yield estimates, measurement, analysis | Using harvesters often reduces the capability to apply fertilizer and plant protection in the most optimal way, as well as to harvest the best grapes, which can be overcome by precise digital field records. | Better planning capabilities-building for reducing unnecessary work steps, optimize existing ones in scale and scope. | |

| Generational change- new managerial routines | New generation of vintners is more open to digital technologies and even demands them or even build them themselves. This is especially pronounced after company take-over. | The new generation of vintners and wine entrepreneurs are digital natives and see digital technologies as the only way of doing things, regardless of the previous managerial traditions. | |

| Faster decision-making, especially during the harvest | Wine entrepreneurs need to coordinate a large number of different stakeholders effectively under tight schedule | Wine entrepreneurs need the capability of being able to make fast decisions in order to keep the high pace of daily duties | |

| Fieldwork/cellar assistance | Better risk assessment (excess ripeness, storm weather) | Wine professionals need reliable and networked tools for assessment of risks. | Making better decisions for reducing crisis situations, reducing unnecessary costs and achieving better quality of a product. |

| Adaptation to new, stricter pesticide regulation | Wine professionals are bound by strict and changing regulation which needs to be addressed in a timely manner. | Fulfilling the law requirements with as least effort as possible. | |

| Lack of available staff | Reliable supply of skilled and unskilled workforce is hard to find. | Reducing the need for large workforce in the production process. | |

| Higher quality products | Higher quality product means the opportunity for higher prices. | Gaining competitive advantage over competition. | |

| Precise logistics/coordination of work in the field | Better time-management of the workforce as well as grape processing to in order to lose as least quality due to unforeseen events as possible, for example unwanted fermentation in the sun. | Reducing waste in the production process and thereby making savings. | |

| Precise and easy documenting of the work | Fieldwork is very hard to control and document without digital tools. | Better human resource practices in relation to the real work documented- rewards, breaks, productivity | |

| Possibility of fine tuning for high quality wines | High quality wines need different tuning possibilities along the production process. | Capability-building for answering to every taste profile change in the market and delivering precisely the taste notes needed by the market. | |

| Automatization of high grape volume processes | High volume grape sorting can be automatized. | No extra workforce needed, thereby reducing many extra work steps in finding, skilling and deploying workforce. | |

| Better capacity planning and less overload of machinery | Different technological solutions in the field and in the cellar need to be coordinated so that there are no excess capacities as well a no overloads. | Long-term investment planning to avoid incompatible technologies and/or possible losses incurred by misdirected investments | |

| Demarcation of diseased areas for avoiding mass panic | Having a capability of clearly identifying plants affected by certain disease can avoid treating the whole vineyard and potentially spreading the panic to other vintners in the area. | Clearly delineating risks and addressing them properly. | |

| Gaining competitive advantage | Competitive pressure on lowering the production cost | The wine industry is very competitive and economies of scale are very important. | Providing the lowest price possible in certain price ranges. |

| Possibilities for benchmarking productivity | Digital tracking of activities and productivity can enhance industry benchmarking, | Identifying the possibilities for further optimization of processes. | |

| Refreshing the winery’s image | Deploying the newest or the most exotic technology can enhance the company image inside the industry itself. | Presenting the winery as future-oriented and innovative. | |

| Value added and ease of use | The new technology introduced needs to be highly practical and usable as vintners are no hackers or digital natives. | The vintner needs to see clear value added from new processes and he has to clearly understand the way it can be deployed. |

Appendix B

| First-Order Codes | Description of the Opportunity | Motivation for Seizing the Opportunity | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Advances in geoinformatics and robotics | GPS tracking of machines through an application | All the vehicles in the field can be controlled via one interface. | Increasing the coordination and planning capability, as well the quality of short-term decision-making. |

| Advanced digital field records for precise harvest mapping | Digital records are the basis for connecting all other devices through an interface. | Reducing excess costs and new possibilities through different digital devices, many still in experimental use. | |

| Remote grape quality and yield assessment | Getting the data from the field with no need to be present all the time. | Reducing field visits during ripening period and better resource planning. | |

| Advances in technology convergence, connectivity, usability | Scale integrated into loading bin harvester or drive-over scale | Integrated scales can help with getting the data on the quantity of grapes for processing. | Better planning of the grape processing for lower costs and higher quality. |

| Cheap, mobile sensors (spectrometer)+ GPS+ tractor/robot | New affordable sensors are being developed for different kinds of devices and for different uses. | Enhancing capabilities of existing hardware with low additional investments needed. | |

| Enhanced usability of interface and multilingual support | Interfaces between different hardware and software components need to be optimized as well as usability for a diverse workforce. | New devices need to be compatible with old ones and design for use by an international workforce. | |

| Cost-effective inline measuring devices | Affordable solutions need to be developed in order to enhance grape and wine processing even further. | Higher quality wine on a relatively tight budget. | |

| Digital transfer of production data to wine traders | The digitalization of production data enables automatic transfer of data to wine traders, enabling the customers to profit from better and more reliable data in an otherwise complex industry. | Providing production data in a modern and accessible way with no extra cost of additional certification. | |

| Remote maintenance of machines | There is a possibility to conduct remote maintenance for some high-end grape processing facilities. | Time and effort saving, better coordination with technical support. | |

| Advances in machine learning | Artificial Intelligence (AI)- assisted harvester (automatic turn off function for bad areas) | New harvesters are being launched on the market, which can automatically recognize bad grapes and not harvest them. | Considerable quality improvement closer to hand harvest, with no extra effort needed by the harvester driver. |

| Big data analytics | Putting to use an abundance of historical digital data in some historic companies in order to make better decision in relation to weather, ripening and harvest timing. | Harness the power of experience currently buried in decades of unused historical data, to enhance the vintner decision-making as well as capabilities of machinery. |

Appendix C

| Questions for Wineries | Questions for Wine Software and Hardware Producers |

|---|---|

| 1. Please describe the harvest planning process in your company in detail (which actors are involved, which routines have been developed, which technologies are being used, how long does the whole process lst, which key competences and capabilities are needed?). | 1. What are the latest Industry 4.0 technologies that could be used for grape ripeness measurement, harvest planning and harvesting itself? Which technologies have already been implemented, which are coming soon and which have already been used in other areas of agriculture? |

| 2. How does the digitalization of data transfer between grape growing grape and grape must processing look like in your company? | 2. Which key competencies and skills are required or will be required in the future? How well is the (university) education adapted to these changes? To what extent is (university) education pursuing or promoting these changes? |

| 3. Which data are available in digitalized form, at which pace, and what are the expectations/needs from the company in this sense? (Geolocated information, Vineyard types, GPS technology or other, planned vs. Actual harvest, grape variety, quality parameters, must weight, acidity, extent of decay, type of decay, etc.- which optimizations in this sense would benefit the most the production process?) | 3. To what extent is the data transfer between grape production and grape processing already digitalized? |

| 4. What motivates the optimization of interfaces between different IT systems in your company? | 4. Which data is already digitalized (from a technical point of view), at what speed can they be delivered? (e.g., geo-positioning—via GPS or otherwise, harvest volume: estimated and actual, grape variety, quality parameters such as must weight/acidity, botrytis content, type of decay, etc.) |

| 5. What is the structure of your employees when it comes to the digitization perspective or motivation for digitization? (Are there differences in the acceptance of digitalization? If so, which ones and why?) | 5. Which data could be digitized (from a technical point of view) and at what speed could it be delivered? (e.g., geo-positioning- via GPS or otherwise, harvest volume: estimated and actual, grape variety, quality parameters such as must weight/acidity, botrytis content, type of decay, etc.) |

| 6. If you use harvesters: how does the planning and consultation work with regard to harvester take place? (Do you harvest according to local availability or are quality aspects in the foreground?) | 6. Which Industry 4.0 technologies could be used in terms of planning and consultation with the harvester? |

| 7. How do you deal with purchased goods (grapes, must or wine)? | 7. What could the latest technologies do when it comes to product traceability systems? (e.g., because of product safety and faster collection of defective series, traceability of sales of products back to raw material receipt) |

| 8. What are the needs regarding tools/systems for product traceability? (e.g., because of security and quick collection of faulty series—from sales of the products back to raw material receipt) | 8. How dynamic have changes and innovations in harvest planning been over the past 10 years? (What has changed? To what extent?) |

| 9. How dynamic have the changes and innovations of harvest planning been over the past 10 years? (What has changed? To what extent?) | 9. What is the outlook for the changes and innovations in the area of harvest planning in the next 10 years? (What will change? To what extent?) |

| 10. Have measures to improve the harvest planning process and/or grape logistics already been planned? (If yes, which?) | |

| 11. What are the priorities for innovation in your company? (Please give examples for each applicable category: increase in efficiency—less waste of resources, increase in effectiveness—achieve goals with greater success, increase quality—produce products with higher/more stable quality) | |

| 12. How do you deal with innovations? (More carefully, step by step, or rather as a paradigm shift and one-off, radical change) |

References

- Teece, D.J. Explicating dynamic capabilities: The nature and microfoundations of (sustainable) enterprise performance. Strat. Manag. J. 2007, 28, 1319–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Duarte Alonso, A.; Kok, S.; O’Shea, M. Family Businesses and Adaptation: A Dynamic Capabilities Approach. J. Fam. Econ. Issues 2018, 39, 683–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Warner, K.S.R.; Wäger, M. Building dynamic capabilities for digital transformation: An ongoing process of strategic renewal. Long Range Plan. 2019, 52, 326–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barykin, S.Y.; Kapustina, I.V.; Kirillova, T.V.; Yadykin, V.K.; Konnikov, Y.A. Economics of Digital Ecosystems. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2020, 6, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingrassia, M.; Altamore, L.; Bacarella, S.; Columba, P.; Chironi, S. The Wine Influencers: Exploring a New Communication Model of Open Innovation for Wine Producers—A Netnographic, Factor and AGIL Analysis. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2020, 6, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirner, E.; Kinkel, S.; Jaeger, A. Innovation paths and the innovation performance of low-technology firms—An empirical analysis of German industry. Res. Policy 2009, 38, 447–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isiordia-Lachica, P.C.; Valenzuela, A.; Rodríguez-Carvajal, R.A.; Hernández-Ruiz, J.; Romero-Hidalgo, J.A. Identification and Analysis of Technology and Knowledge Transfer Experiences for the Agro-Food Sector in Mexico. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2020, 6, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pyka, A.; Bogner, K.; Urmetzer, S. Productivity slowdown, exhausted opportunities and the power of Human ingenuity—Schumpeter meets georgescu-roegen. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2019, 5, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shabanov, V.L.; Vasilchenko, M.Y.; Derunova, E.A.; Potapov, A.P. Formation of an Export-Oriented Agricultural Economy and Regional Open Innovations. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2021, 7, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajudeen, F.P.; Jaafar, N.I.; Sulaiman, A. External Technology Acquisition and External Technology Exploitation: The Difference of Open Innovation Effects. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2019, 5, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- West, J.; Bogers, M. Leveraging external sources of innovation: A review of research on open innovation. J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 2014, 31, 814–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlosser, S.; Toninelli, D.; Cameletti, M. Comparing Methods to Collect and Geolocate Tweets in Great Britain. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2021, 7, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaborovskaia, O.; Nadezhina, O.; Avduevskaya, E. The Impact of Digitalization on the Formation of Human Capital at the Regional Level. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2020, 6, 184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, A.; Madi, Y.; Abuhashesh, M.; Nusairat, N.M.; Masa’deh, R. The Knowledge, Attitude, and Practice of the Adoption of Green Fashion Innovation. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2020, 6, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, H.; Shin, K.; Kim, E.; Kim, S. Does Open Innovation Enhance a Large Firm’s Financial Sustainability? A Case of the Korean Food Industry. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2020, 6, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, S.-H.; Kim, J.; Choi, Y. Compassion and Workplace Incivility: Implications for Open Innovation. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2021, 7, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chanias, S.; Myers, M.D.; Hess, T. Digital transformation strategy making in pre-digital organizations: The case of a financial services provider. J. Strat. Inf. Syst. 2019, 28, 17–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loonam, J.; Eaves, S.; Kumar, V.; Parry, G. Towards digital transformation: Lessons learned from traditional organizations. Strateg. Chang. 2018, 27, 101–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritter, T.; Pedersen, C.L. Digitization capability and the digitalization of business models in business-to-business firms: Past, present, and future. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2020, 86, 180–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobbs, M.; Owen, S.; Gerber, L. Liquid love? Dating apps, sex, relationships and the digital transformation of intimacy. J. Sociol. 2017, 53, 271–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tabrizi, B.; Lam, E.; Girard, K.; Irvin, V. Digital transformation is not about technology. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2019, 13, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Verhoef, P.C.; Broekhuizen, T.; Bart, Y.; Bhattacharya, A.; Dong, J.Q.; Fabian, N.; Haenlein, M. Digital transformation: A multidisciplinary reflection and research agenda. J. Bus. Res. 2021, 122, 889–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fachrunnisa, O.; Adhiatma, A.; Ab Majid, M.N.; Lukman, N. Towards SMEs’ digital transformation: The role of agile leadership and strategic flexibility. J. Small Bus. Strategy 2020, 30, 65–85. [Google Scholar]

- Dressler, M.; Paunovic, I. Converging and diverging business model innovation in regional intersectoral cooperation–exploring wine industry 4.0. Eur. J. Innov. Manag. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berman, S.J. Digital transformation: Opportunities to create new business models. Strategy Leadersh. 2012, 40, 16–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank, A.G.; Mendes, G.H.S.; Ayala, N.F.; Ghezzi, A. Servitization and Industry 4.0 convergence in the digital transformation of product firms: A business model innovation perspective. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2019, 141, 341–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loebbecke, C.; Picot, A. Reflections on societal and business model transformation arising from digitization and big data analytics: A research agenda. J. Strat. Inf. Syst. 2015, 24, 149–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hull, C.; Hung, Y.-T.; Hair, N. Digital entrepreneurship. EDGE 2006. Available online: https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/145030462.pdf (accessed on 26 April 2021).

- Cavaleri, S.; Shabana, K. Rethinking sustainability strategies. J. Strategy Manag. 2018, 11, 2–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carayannis, E.G.; Sindakis, S.; Walter, C. Business Model Innovation as Lever of Organizational Sustainability. J. Technol. Transf. 2014, 40, 85–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sexton, M.; And, P.B.; Aouad, G. Motivating small construction companies to adopt new technology. Build. Res. Inf. 2006, 34, 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, S. Two efficiency-driven networks on a collision course: ALDI’s innovative grocery business model vs Walmart. Strategy Leadersh. 2017, 45, 18–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osterwalder, A.; Pigneur, Y. Business Model Generation: A Handbook for Visionaries, Game Changers, and Challengers; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Gaimon, C.; Özkan, G.F.; Napoleon, K. Dynamic Resource Capabilities: Managing Workforce Knowledge with a Technology Upgrade. Organ. Sci. 2011, 22, 1560–1578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kane, G.C. The workplace of the future. MIT Sloan Manag. Rev. 2015, 56. Available online: https://sloanreview.mit.edu/article/the-workplace-of-the-future/ (accessed on 26 April 2021).

- Ramarajan, L.; Reid, E. Shattering the myth of separate worlds: Negotiating nonwork identities at work. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2013, 38, 621–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, M.; Nandhakumar, J.; Mattila, M. Balancing fluid and cemented routines in a digital workplace. J. Strat. Inf. Syst. 2020, 29, 101616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colbert, A.; Yee, N.; George, G. The digital workforce and the workplace of the future. Acad. Manag. J. 2016, 59, 731–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Köffer, S. Designing the digital workplace of the future–what scholars recommend to practitioners. In Proceedings of the ICIS 2015, Fort Worth, TX, USA, 13–16 December 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Carranza, G.; Garcia, M.; Sanchez, B. Activating inclusive growth in railway SMEs by workplace innovation. Transp. Res. Interdiscip. Perspect. 2020, 7, 100193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meske, C. Digital Workplace Transformation–On The Role of Self-Determination in the Context of Transforming Work Environments. In Proceedings of the ECIS 2019, Leuven, Belgium, 8–13 September 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Meske, C.; Junglas, I. Investigating the elicitation of employees’ support towards digital workplace transformation. Behav. Inf. Technol. 2020, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attaran, M.; Attaran, S.; Kirkland, D. Technology and organizational change: Harnessing the power of digital workplace. In Handbook of Research on Social and Organizational Dynamics in the Digital Era; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2020; pp. 383–408. [Google Scholar]

- Attaran, M.; Attaran, S.; Kirkland, D. The need for digital workplace: Increasing workforce productivity in the information age. Int. J. Enterp. Inf. Syst. (IJEIS) 2019, 15, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kissmer, T.; Knoll, J.; Stieglitz, S.; Groß, R. Knowledge workers’ expectations towards a digital workplace. In Proceedings of the AMCIS 2018, New Orleans, LA, USA, 16–18 August 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Zimmer, M.P.; Baiyere, A.; Salmela, H. Digital Workplace Transformation: The Importance of Deinstitutionalising the Taken for Granted. In Proceedings of the ECIS 2020, Marrakech, Morocco, 15–17 June 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Cherry, M.A. Beyond misclassification: The digital transformation of work. Comp. Labor Law Policy J. Forthcom. 2016, 37, 544–577. [Google Scholar]

- Goles, T.; Hawk, S.; Kaiser, K.M. Information technology workforce skills: The software and IT services provider perspective. Inf. Syst. Front. 2008, 10, 179–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, C.M.; Bower, J.L. Customer power, strategic investment, and the failure of leading firms. Strat. Manag. J. 1996, 17, 197–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gärtner, C.; Schön, O. Modularizing business models: Between strategic flexibility and path dependence. J. Strategy Manag. 2016, 9, 39–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peter, M.K.; Kraft, C.; Lindeque, J. Strategic action fields of digital transformation. J. Strategy Manag. 2020, 13, 160–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Storbacka, K.; Windahl, C.; Nenonen, S.; Salonen, A. Solution business models: Transformation along four continua. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2013, 42, 705–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, A.; Brady, T.; Hobday, M. Charting a path toward integrated solutions. MIT Sloan Manag. Rev. 2006, 47, 39. [Google Scholar]

- Spencer, A.J.; Buhalis, D.; Moital, M. A hierarchical model of technology adoption for small owner-managed travel firms: An organizational decision-making and leadership perspective. Tour. Manag. 2012, 33, 1195–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souder, D.; Zaheer, A.; Sapienza, H.; Ranucci, R. How family influence, socioemotional wealth, and competitive conditions shape new technology adoption. Strat. Manag. J. 2017, 38, 1774–1790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- König, A.; Kammerlander, N.; Enders, A. The Family Innovator’s Dilemma: How Family Influence Affects the Adoption of Discontinuous Technologies by Incumbent Firms. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2013, 38, 418–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cullen, R.; Forbes, S.L.; Grout, R. Non-adoption of environmental innovations in wine growing. N. Z. J. Crop Hortic. Sci. 2013, 41, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forbes, S.L.; Cullen, R.; Grout, R. Adoption of environmental innovations: Analysis from the Waipara wine industry. Wine Econ. Policy 2013, 2, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dolińska, M. Knowledge based development of innovative companies within the framework of innovation networks. Innovation 2015, 17, 323–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolfsma, W.; van der Eijk, R. Behavioral Foundations for Open Innovation: Knowledge Gifts and Social Networks. Innovation 2017, 19, 287–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pachura, A. Innovation and change in networked reality. Pol. J. Manag. Stud. 2017, 15, 173–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rebelo, J.; Muhr, D. Innovation in wine SMEs: The Douro Boys informal network. Stud. Agric. Econ. 2012, 114, 111–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pullen, A.J.J.; de Weerd-Nederhof, P.C.; Groen, A.J.; Fisscher, O.A.M. Open Innovation in Practice: Goal Complementarity and Closed NPD Networks to Explain Differences in Innovation Performance for SMEs in the Medical Devices Sector. J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 2012, 29, 917–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siu, W.-S.; Bao, Q. Network Strategies of Small Chinese High-Technology Firms: A Qualitative Study. J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 2008, 25, 79–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pullen, A.; de Weerd-Nederhof, P.C.; Groen, A.J.; Fisscher, O.A.M. SME Network Characteristics vs. Product Innovativeness: How to Achieve High Innovation Performance. Creat. Innov. Manag. 2012, 21, 130–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dogbe, C.S.K.; Tian, H.; Pomegbe, W.W.K.; Sarsah, S.A.; Otoo, C.O.A. Effect of network embeddedness on innovation performance of small and medium-sized enterprises. J. Strategy Manag. 2020, 13, 181–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Union. User Guide to the SME Definition; European Commission: Luxembourg, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Nadkarni, S.; Prügl, R. Digital transformation: A review, synthesis and opportunities for future research. Manag. Rev. Q. 2021, 71, 233–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Schumacher, S.; Pokorni, B.; Himmelstoß, H.; Bauernhansl, T. Conceptualization of a Framework for the Design of Production Systems and Industrial Workplaces. Procedia CIRP 2020, 91, 176–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, S.P.; Schubert, P. Designs for the digital workplace. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2018, 138, 478–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matricano, D.; Sorrentino, M. Implementation of regional innovation networks: A case study of the biotech industry in Campania. Sinergie Ital. J. Manag. 2015, 33, 105–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leitão, J.; Pereira, D.; Brito, S.d. Inbound and Outbound Practices of Open Innovation and Eco-Innovation: Contrasting Bioeconomy and Non-Bioeconomy Firms. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2020, 6, 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Grape berry/must assessment | Inf. 28 | “Take a look at Bordeaux, they go and bite the kernels to check whether they taste bitter, woody or green. Sensory tests are essential! I think the consciousness of physiological maturity receives more attention in other countries (than in Germany).” |

| Multi-year field data collection in a database | Inf. 24 | “We work in an Informix database… and the historical values of our company go back to the mid 80’s… We are not in the cloud, the database is located in clients’ servers… reverse tracking is important… this data is being backtracked by vintners themselves…our software makes that possible… the vintner can trace every wine to its creation, every processing step that he made, every substance that he had added, he can document, even above the wine law requirements. This infrastructure is available and is also used, at least partially.” |

| Fieldwork logistics and visualisation of processes | Inf. 12 | “A tremendous relief of the working day is useable information, no matter where one is located. I notice this now, that I can access my whole cellar book from my phone: as if I am standing on the tank and saying “how is the tank doing”?” |

| Inf. 16 | “If I optimize the interface and identify on the tablet that “he is there” or “this is going on there”, and have that on the PC or on the screen, I have less stress. This is because I can than identify certain risks better. I have less tension and get a better picture; this is very important…We are three managers, and there is some degree of exchange between us, but we still need to know what’s going on and plan accordingly. The important part of a day is that certain data and facts are being updated quickly.” | |

| Inf. 29 | “… our dream would be to visualize all our vineyards. It allows to visualize both the locations of my customers (B2B), my suppliers, as well as vineyards. A further dream would be to have must weight, acidity and rot-affected areas, so harvesting can be directed precisely.” |

| Management assistance | Inf. 16 | “The sensors are from company X… It costs money, no question, but the choice is between money and safety. And if I have safety, then I can work better with my people and my customers and not have that much stress. Especially in the harvesting phase, it’s about avoiding stress and that’s what we have to get rid of. We have to relieve the strain of the manager, that’s what we need to do.” |

| Inf. 30 | “… we had a lot of winery successions (regarding wineries as customers of software producers) and the people are just better educated, have different vision of running a winery, and this is an absolute plus point. The market is growing for these technologies and when I project this into the future, from monitoring of vegetation processes in the field to sales, everything will be one digitalized track that monitors all these processes.” | |

| Fieldwork/cellar assistance | Inf. 6 | “I have to take a look at the spot how ripe the grapes are. We have Excel sheets where we write down what we want to do and this is than verified every day to check for changes.” |

| Inf. 6 | “All possible (communication) options are present, from Email, WhatsApp, Phone and personal contact, depending on the situation. If it concerns everybody, then it is posted to WhatsApp group and when it is about instructions to the fieldworkers, then it is one on one.” | |

| Inf. 21 | “It is very important for us to see the progress of the work. During the last harvest, a voluminous harvest, it was very important to us to see how well did we progress and how much surface from which grape variety have we processed and how much is still left to be done. Also, regarding how much we are allowed to harvest: do we have to leave it as it is or how are we going to divide it? These are the things that one otherwise does more through gut instinct and rough estimates, and here it is pretty precise… It is about dividing the workforce and estimating how long do we still need with how much workforce.” | |

| Gaining competitive advantage | Inf. 7 | “We are committed to innovation and plan accordingly. We have dealt with it intensively, we also have a conversation tomorrow, the grape selection plant, optical sorting. The cost pressure drives this decision. I think people cost us too much money. 15 people do a lot of work and I think this people management is a huge problem, also because I cannot get any German workers. So that means I have to do the work, but without workers. This will be a solution that will be faster, but I don’t think it will be better.” |

| Inf. 24 | “The more ambitious they (the wineries) are, and the higher the quality they produce, the more they ask for such quality-optimizing options: to select as soon as possible, what will I get when and whom do I assign the order. The Pino Gris- I don’t need 14.5% as in the 2018 harvest. I would like 13.5% alcohol, so it is easily digestible, with higher acidity, etc. These are the elements that are interesting for quality and are of interest for many users, because there is an added value behind this that is reflected in the quality and thus in the revenues.” |

| Advances in geoinformatics | Inf. 23 | “This foreknowledge capability, in which field do I have which oechsle degrees [measuring the sugar content in the grapes] or anthocyanin, that you can get with one hand pass. This is so advanced that there are this Eurorobots who tackle this. The research center X was also a partner on this project. But in Germany they are not allowed to drive through the field- in Spain yes, because they have different legislation. I see this from the perspective that our goal should than be harvester, that could provide different information- most weight, etc. This data should be delivered in order to support this smart spinning systems. Harvesters can already do a phenotype reading.” |

| Inf. 29 | “…can we not attach a kind of scanner (on the tractor)? We have so many passes through the vineyard for crop protection, leaf trimming, etc. If a simple and affordable system had scanned the leaves to assess if they look dry, are they dark green or yellowish, you could detect the grape color. These would be simple sensory systems that could inform the application if there is a dry or wet zone. This would be helpful things, especially for harvesting later.” | |

| Advances in technology convergence, connectivity, usability | Inf. 28 | “We often have the requirement for the process data to be sent digitally from the press to an external location and thereby do a proactive maintenance, because for example, a valve could break. In addition, to the oenological side, this is very interesting and useful story where digitalization could be applied. This is remote control, so that we as a manufacturer can make remote maintenance and the press is often ready for use much faster than if the serviceman had come.” |

| Advances in machine learning | Inf. 23 | “there are currently some companies in Germany which deal with precision viticulture. There is the Fraunhofer, there is the Geobox, there are several places that can do this, at least for precision fertilization. Some rely on satellite data, some measure with drones or with NDVI and others with sensors in the vineyard. They all have their algorithms…And they then also network the devices for fertilizer application, also zone-dependent fertilizing” |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dressler, M.; Paunovic, I. Sensing Technologies, Roles and Technology Adoption Strategies for Digital Transformation of Grape Harvesting in SME Wineries. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2021, 7, 123. https://doi.org/10.3390/joitmc7020123

Dressler M, Paunovic I. Sensing Technologies, Roles and Technology Adoption Strategies for Digital Transformation of Grape Harvesting in SME Wineries. Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity. 2021; 7(2):123. https://doi.org/10.3390/joitmc7020123

Chicago/Turabian StyleDressler, Marc, and Ivan Paunovic. 2021. "Sensing Technologies, Roles and Technology Adoption Strategies for Digital Transformation of Grape Harvesting in SME Wineries" Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity 7, no. 2: 123. https://doi.org/10.3390/joitmc7020123

APA StyleDressler, M., & Paunovic, I. (2021). Sensing Technologies, Roles and Technology Adoption Strategies for Digital Transformation of Grape Harvesting in SME Wineries. Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity, 7(2), 123. https://doi.org/10.3390/joitmc7020123