Continuous Intention to Use E-Wallet in the Context of the COVID-19 Pandemic: Integrating the Health Belief Model (HBM) and Technology Continuous Theory (TCT)

Abstract

:1. Introduction

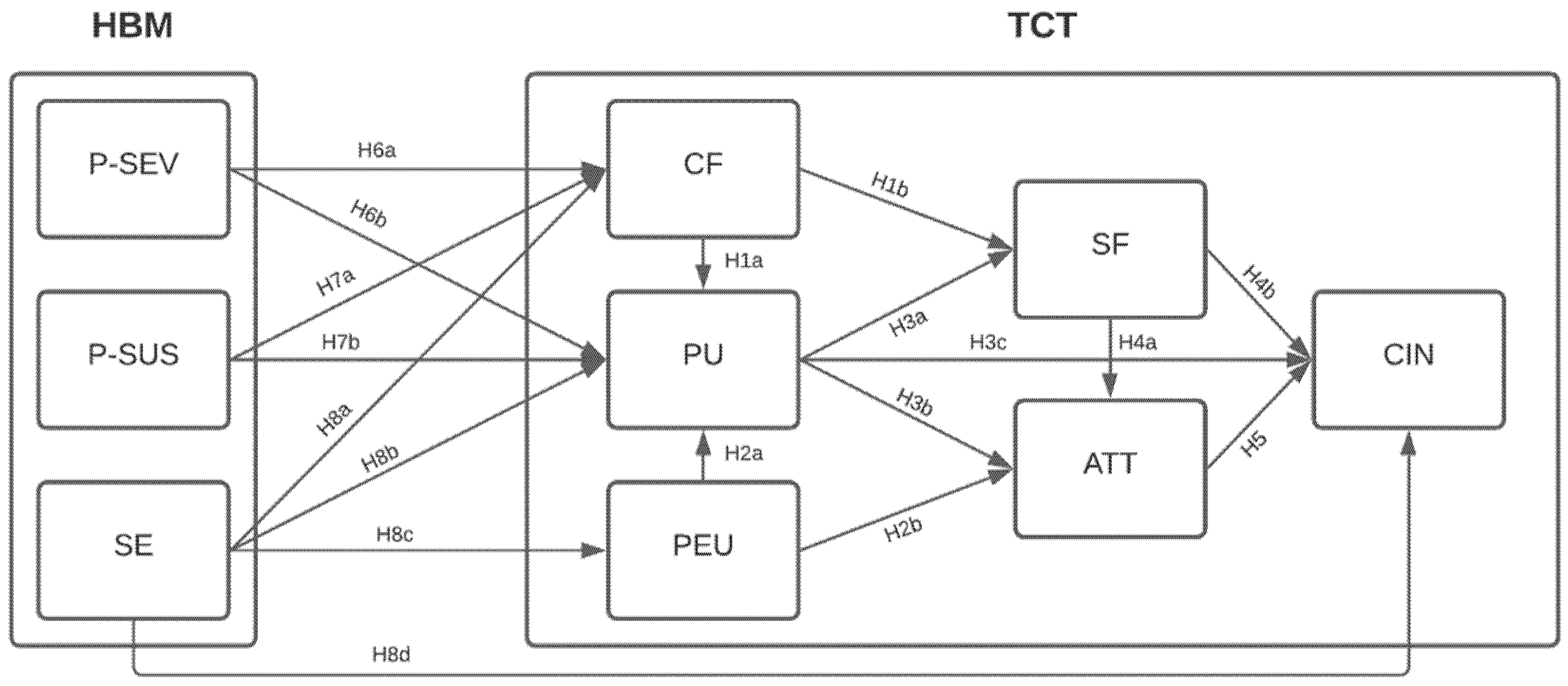

2. Conceptual Framework and Hypothesis Development

2.1. Technology Continuous Theory (TCT)

2.2. Health Belief Model (HBM)

2.3. Integrating HBM and TCT

2.4. Hypotheses Development

2.4.1. TCT

2.4.2. HBM

3. Methodology

3.1. Survey Development

3.2. Data Collection

3.3. Data Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Common Method Bias (CMB)

4.2. Measurement Model

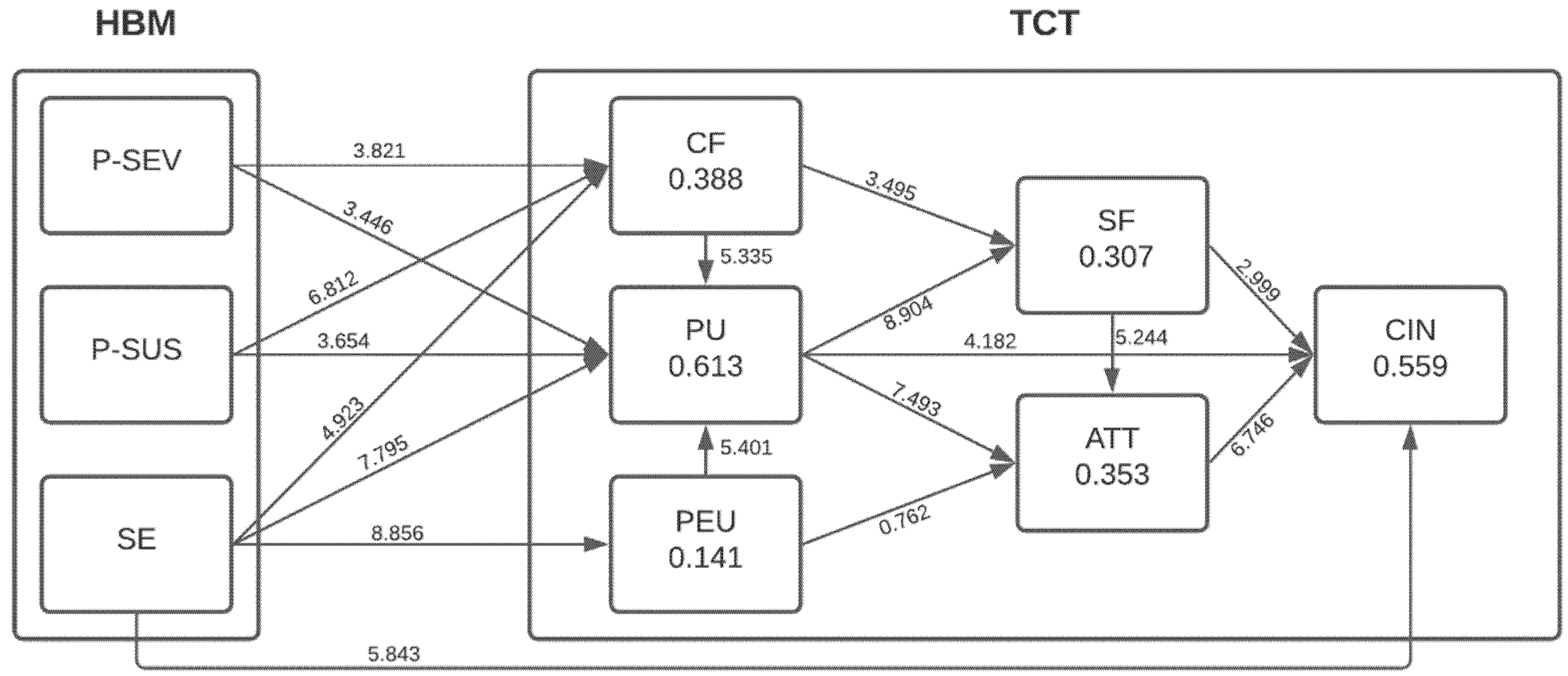

4.3. Structural Model

Evaluating Predictive Relevance and Effect Sizes

4.4. Importance-Performance Map Analysis

5. Discussion

6. Theoretical and Managerial Implications

7. Conclusions

8. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| N | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Male | 606 | 55.9 |

| Female | 474 | 44.1 |

| Total | 1080 | 100% |

| Age | ||

| Less than 25 | 468 | 43.3 |

| 25 to 40 | 384 | 35.6 |

| 40 to 55 | 162 | 15 |

| Above 55 | 66 | 6.1 |

| Total | 1080 | 100% |

| Education level | ||

| Bachelor | 514 | 47.6 |

| Master | 296 | 27.4 |

| Ph.D. | 214 | 19.8 |

| Others | 56 | 5.2 |

| Total | 1080 | 100% |

| Occupation | ||

| Student | 768 | 71.1 |

| Lecturer | 172 | 15.9 |

| Administrator | 92 | 8.5 |

| Others | 48 | 4.5 |

| Total | 1080 | 100% |

| E-Wallet usage frequency during the COVID-19 pandemic | ||

| Once a month | 128 | 11.9 |

| 2 to 5 times a month | 226 | 20.9 |

| 6 to 10 times a month | 522 | 48.3 |

| More than 10 times a month | 204 | 18.9 |

| Total | 1080 | 100% |

Appendix B

| Constructs | Item Loading |

|---|---|

| Perceived Severity (P-SEV) | |

| P-SEV1: Thinking about getting infected by SARS-CoV-2 due to using cash or physical contact payment tools makes me nervous. | 0.801 |

| P-SEV2: I am afraid to think about the health problems of getting infected by SARS-CoV-2 if I use cash or physical contact payment tools. | 0.827 |

| P-SEV3: If I get infected by SARS-CoV-2 due to using cash or physical contact payment tools, my whole life would change. | 0.842 |

| Perceived Susceptibility (P-SUS) | |

| P-SUS1: There is a possibility to get infected by SARS-CoV-2 due to using cash or physical contact payment tools. | 0.832 |

| P-SUS2: My chances of infected by SARS-CoV-2 if I use cash or physical contact payment tools are high. | 0.784 |

| P-SUS3: I feel that SARS-CoV-2 will develop health problems to me in the future. | 0.795 |

| Self-Efficacy (SE) | |

| SE1: It would be easy for me to learn how to use e-wallet systems. | 0.813 |

| SE2: I could use e-wallet if someone showed me how to do it. | 0.835 |

| SE3: I can use e-wallet if there is no one around to tell me what to do. | 0.807 |

| Confirmation (CF) | |

| CF1: My experience with using e-wallet was better than what I expected. | 0.769 |

| CF2: The service level provided by e-wallet was better than what I expected. | 0.826 |

| CF3: Overall, most of my expectations from using e-wallet were confirmed. | 0.791 |

| Perceived Ease of Use (PEU) | |

| PEU1: e-wallet is easy to use. | 0.809 |

| PEU2: I feel comfortable while using e-wallets. | 0.785 |

| PEU3: it is easy to use e-wallet more frequently. | 0.821 |

| Perceived Usefulness (PU) | |

| PU1: using e-wallet improves my performance in managing personal payments. | 0.798 |

| PU2: e-wallet saves time in making payments. | 0.817 |

| PU3: overall, e-wallet is useful in managing payments. | 0.803 |

| Satisfaction (SF) | |

| SF1: I feel satisfied with e-wallet usage. | 0.840 |

| SF2: I feel contented with e-wallet usage. | 0.869 |

| SF3: I feel happy using e-wallet service. | 0.845 |

| Attitude (ATT) | |

| ATT1: Using e-wallet for payment would be a wise idea. | 0.794 |

| ATT2: I like the idea of using e-wallet for payment. | 0.763 |

| ATT3: Using e-wallet would be a pleasant experience. | 0.834 |

| Continuous Intention (CIN) | |

| CIN1: I intend to continue using e-wallet rather than discontinue its use. | 0.775 |

| CIN2: My intentions are to continue using e-wallet than using any alternative means. | 0.797 |

| CIN3: if I could, I would like to continue my use of e-wallet as much as possible. | 0.820 |

Appendix C

| ATT | CF | CIN | P-SEV | P-SUS | PEU | PU | SE | SF | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ATT | |||||||||

| CF | 0.599 | ||||||||

| CIN | 0.837 | 0.676 | |||||||

| P-SEV | 0.734 | 0.663 | 0.797 | ||||||

| P-SUS | 0.531 | 0.700 | 0.547 | 0.580 | |||||

| PEU | 0.430 | 0.675 | 0.457 | 0.428 | 0.537 | ||||

| PU | 0.744 | 0.834 | 0.827 | 0.756 | 0.749 | 0.726 | |||

| SE | 0.807 | 0.722 | 0.846 | 0.790 | 0.645 | 0.489 | 0.841 | ||

| SF | 0.632 | 0.592 | 0.705 | 0.570 | 0.470 | 0.373 | 0.678 | 0.766 |

References

- Seale, H.; Dyer, C.; Abdi, I.; Rahman, K.M.; Sun, Y.; Qureshi, M.O.; Dowell-Day, A.; Sward, J.; Islam, M.S. Improving the impact of non-pharmaceutical interventions during COVID-19: Examining the factors that influence engagement and the impact on individuals. BMC Infect. Dis. 2020, 20, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carracedo, P.; Puertas, R.; Marti, L. Research lines on the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on business. A text mining analysis. J. Bus. Res. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonker, N.; Van Der Cruijsen, C.; Bijlsma, M.; Bolt, W. Pandemic Payment Patterns. SSRN Electron. J. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sikri, A.; Dalal, S.; Singh, N.; Le, D.-N. Mapping of e-Wallets With Features. Cyber Secur. Parallel Distrib. Comput. 2019, 245–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auer, R.; Cornelli, G.; Frost, J. BIS Bulletin Payments, no. 3. 2020, p. 7. Available online: www.bis.org (accessed on 9 February 2021).

- Pal, R.; Bhadada, S.K. Cash, currency and COVID-19. Postgrad. Med. J. 2020, 96, 427–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu Daqar, M.; Constantinovits, M.; Arqawi, S.; Daragmeh, A. The role of Fintech in predicting the spread of COVID-19. Banks Bank Syst. 2021, 16, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- About Hungary—Coronavirus Update: Contactless Payment Limit Raised to HUF 15,000 to Help Reduce Virus. Available online: http://abouthungary.hu/news-in-brief/coronavirus-update-contactless-payment-limit-raised-to-fifteen-thousand-forints-this-too-serves-to-slow-down-spread-of-the-virus/ (accessed on 9 February 2021).

- Ruiz-Real, J.L.; Nievas-Soriano, B.J.; Uribe-Toril, J. Has Covid-19 Gone Viral? An Overview of Research by Subject Area. Health Educ. Behav. 2020, 47, 861–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizun, M.; Strzelecki, A. Students’ Acceptance of the COVID-19 Impact on Shifting Higher Education to Distance Learning in Poland. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 6468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahi, S.; Khan, M.M.; Alghizzawi, M. Factors influencing the adoption of telemedicine health services during COVID-19 pandemic crisis: An integrative research model. Enterp. Inf. Syst. 2020, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salem, M.A.; Nor, K.M. The Effect of COVID-19 on Consumer Behaviour in Saudi Arabia: Switching From Brick And Mortar Stores To E-Commerce. Int. J. Sci. Technol. Res. 2020, 9, 15–28. [Google Scholar]

- Prasetyo, Y.; Tanto, H.; Mariyanto, M.; Hanjaya, C.; Young, M.; Persada, S.; Miraja, B.; Redi, A. Factors Affecting Customer Satisfaction and Loyalty in Online Food Delivery Service during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Its Relation with Open Innovation. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2021, 7, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahabi, V.; Azar, A.; Razi, F.F.; Shams, M.F.F. Simulation of the effect of COVID-19 outbreak on the development of branchless banking in Iran: Case study of Resalat Qard–al-Hasan Bank. Rev. Behav. Finance 2020, 13, 85–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Maroof, R.S.; Salloum, S.A.; Hassanien, A.E.; Shaalan, K. Fear from COVID-19 and technology adoption: The impact of Google Meet during Coronavirus pandemic. Interact. Learn. Environ. 2020, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonker, M.; De Bekker-Grob, E.; Veldwijk, J.; Goossens, L.; Bour, S.; Mölken, M.R.-V. COVID-19 Contact Tracing Apps: Predicted Uptake in the Netherlands Based on a Discrete Choice Experiment. JMIR mHealth uHealth 2020, 8, e20741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Nawayseh, M.K. FinTech in COVID-19 and Beyond: What Factors Are Affecting Customers’ Choice of FinTech Applications? J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2020, 6, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puriwat, W.; Tripopsakul, S. Explaining an Adoption and Continuance Intention to Use Contactless Payment Technologies: During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Emerg. Sci. J. 2021, 5, 85–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aji, H.M.; Berakon, I.; Husin, M.M. COVID-19 and e-wallet usage intention: A multigroup analysis between Indonesia and Malaysia. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2020, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gbongli, K.; Xu, Y.; Amedjonekou, K.M. Extended Technology Acceptance Model to Predict Mobile-Based Money Acceptance and Sustainability: A Multi-Analytical Structural Equation Modeling and Neural Network Approach. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- C.C., S.; Prathap, S.K. Continuance adoption of mobile-based payments in Covid-19 context: An integrated framework of health belief model and expectation confirmation model. Int. J. Pervasive Comput. Commun. 2020, 16, 351–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foroughi, B.; Iranmanesh, M.; Hyun, S.S. Understanding the determinants of mobile banking continuance usage intention. J. Enterp. Inf. Manag. 2019, 32, 1015–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahi, S.; Khan, M.M.; Alghizzawi, M. Extension of technology continuance theory (TCT) with task technology fit (TTF) in the context of Internet banking user continuance intention. Int. J. Qual. Reliab. Manag. 2020, 38, 986–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pappas, I.O.; Kourouthanassis, P.E.; Giannakos, M.N.; Chrissikopoulos, V. Sense and sensibility in personalized e-commerce: How emotions rebalance the purchase intentions of persuaded customers. Psychol. Mark. 2017, 34, 972–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Bacao, F. How Does the Pandemic Facilitate Mobile Payment? An Investigation on Users’ Perspective under the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 1016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liao, C.; Palvia, P.; Chen, J.-L. Information technology adoption behavior life cycle: Toward a Technology Continuance Theory (TCT). Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2009, 29, 309–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, F.D. Perceived Usefulness, Perceived Ease of Use, and User Acceptance of Information Technology. MIS Q. 1989, 13, 319–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bhattacherjee, A. Understanding Information Systems Continuance: An Expectation-Confirmation Model. MIS Q. 2001, 25, 351–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, R.L. A Cognitive Model of the Antecedents and Consequences of Satisfaction Decisions. J. Mark. Res. 1980, 17, 460–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hubert, M.; Blut, M.; Brock, C.; Zhang, R.W.; Koch, V.; Riedl, R. The influence of acceptance and adoption drivers on smart home usage. Eur. J. Mark. 2019, 53, 1073–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khayer, A.; Bao, Y. The continuance usage intention of Alipay. Bottom Line 2019, 32, 211–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norman, P.; Conner, M. Health behavior. In The Curated Reference Collection in Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Psychology; UCL IRIS: London, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Janz, N.K.; Becker, M.H. The Health Belief Model: A Decade Later. Health Educ. Q. 1984, 11, 1–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Carpenter, C.J. A Meta-Analysis of the Effectiveness of Health Belief Model Variables in Predicting Behavior. Health Commun. 2010, 25, 661–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kim, S.; Kim, S. Analysis of the Impact of Health Beliefs and Resource Factors on Preventive Behaviors against the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 8666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, L.; Zhou, J.; Zuo, M. Understanding older adults’ intention to share health information on social media: The role of health belief and information processing. Internet Res. 2020, 31, 100–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandler, N.; Krajcsák, Z. Intrapreneurial Fit and Misfit: Enterprising Behavior, Preferred Organizational and Open Innovation Culture. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2021, 7, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Champion, V.L.; Skinner, C.S. Chapter 3: The Health Belief Model. In Health Behavior and Health Education: Theory, Research and Practice, 4th ed.; Jossey-Bass Inc.: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Glanz, K.; Rimer, B.K.; Viswanath, K. Chapter 1: The Scop of Health Behavior and Health Education. In Health Behavior and Health Education: Theory, Research and Practice, 4th ed.; Jossey-Bass Inc.: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Melzner, J.; Heinze, J.; Fritsch, T. Mobile Health Applications in Workplace Health Promotion: An Integrated Conceptual Adoption Framework. Procedia Technol. 2014, 16, 1374–1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wei, J.; Vinnikova, A.; Lu, L.; Xu, J. Understanding and Predicting the Adoption of Fitness Mobile Apps: Evidence from China. Health Commun. 2020, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alaiad, A.; AlSharo, M.; Alnsour, Y. The Determinants of M-Health Adoption in Developing Countries: An Empirical Investigation. Appl. Clin. Inform. 2019, 10, 820–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sari, H.; Othman, M.; Al-Ghaili, A.M. Al-Ghaili, A.M. A Proposed Conceptual Framework for Mobile Health Technology Adoption among Employees at Workplaces in Malaysia. In Advances in Intelligent Systems and Computing; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; Volume 843, pp. 736–748. [Google Scholar]

- Harasis, A.A.; Qureshi, M.I.; Rasli, A. Development of research continuous usage intention of e-commerce. A systematic review of literature from 2009 to 2015. Int. J. Eng. Technol. 2018, 7, 73–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veeramootoo, N.; Nunkoo, R.; Dwivedi, Y.K. What determines success of an e-government service? Validation of an integrative model of e-filing continuance usage. Gov. Inf. Q. 2018, 35, 161–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Awa, H.O.; Ukoha, O.; Igwe, S.R. Revisiting technology-organization-environment (T-O-E) theory for enriched applicability. Bottom Line 2017, 30, 2–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Rahmi, W.M.; Yahaya, N.; Aldraiweesh, A.A.; Alamri, M.M.; Aljarboa, N.A.; Alturki, U.; Aljeraiwi, A.A. Integrating Technology Acceptance Model With Innovation Diffusion Theory: An Empirical Investigation on Students’ Intention to Use E-Learning Systems. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 26797–26809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humbani, M.; Wiese, M. An integrated framework for the adoption and continuance intention to use mobile payment apps. Int. J. Bank Mark. 2019, 37, 646–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, W.; Cho, H.; Chi, C.G. Consumers’ continuance intention to use fitness and health apps: An integration of the expectation–confirmation model and investment model. Inf. Technol. People 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahadzadeh, A.S.; Sharif, S.P.; Ong, F.S.; Khong, K.W. Integrating Health Belief Model and Technology Acceptance Model: An Investigation of Health-Related Internet Use. J. Med Internet Res. 2015, 17, e45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. There is Current Outbreak of Coronavirus (COVID) Disease; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020; Available online: https://www.who.int/health-topics/coronavirus#tab=tab_1 (accessed on 10 December 2020).

- Daneji, A.A.; Ayub, F.M.; Khambari, M.N.M. The effects of perceived usefulness, confirmation and satisfaction on continuance intention in using massive open online course (MOOC). Knowl. Manag. E-Learning 2019, 11, 201–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahi, S.; Ghani, M.A. Integration of expectation confirmation theory and self-determination theory in internet banking continuance intention. J. Sci. Technol. Policy Manag. 2019, 10, 533–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velicia-Martin, F.; Cabrera-Sanchez, J.-P.; Gil-Cordero, E.; Palos-Sanchez, P.R. Researching COVID-19 tracing app acceptance: Incorporating theory from the technological acceptance model. PeerJ Comput. Sci. 2021, 7, e316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazim, C.S.L.M.; Ismail, N.D.B.; Tazilah, M.D.A.K. Application of Technology Acceptance Model (Tam) Towards Online Learning During Covid-19 Pandemic: Accounting Students Perspective. Int. J. Bus. Econ. Law 2021, 24, 13–20. [Google Scholar]

- Hoehle, H.; University of Arkansas; Venkatesh, V. Mobile Application Usability: Conceptualization and Instrument Development. MIS Q. 2015, 39, 435–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vijayasarathy, L.R. Predicting consumer intentions to use on-line shopping: The case for an augmented technology acceptance model. Inf. Manag. 2004, 41, 747–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaikh, A.A.; Karjaluoto, H. Mobile banking adoption: A literature review. Telemat. Inform. 2015, 32, 129–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Munoz-Leiva, F.; Climent-Climent, S.; Liébana-Cabanillas, F. Determinants of Intention to Use the Mobile Banking Apps: An Extension of the Classic TAM Model. SSRN Electron. J. 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, M.; Rezaei, S.; Abolghasemi, M. User satisfaction with mobile websites: The impact of perceived usefulness (PU), perceived ease of use (PEOU) and trust. Nankai Bus. Rev. Int. 2014, 5, 258–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, D.; Wu, W. Understanding mobile shopping consumers’ continuance intention. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2017, 117, 213–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natarajan, T.; Balasubramanian, S.A.; Kasilingam, D.L. The moderating role of device type and age of users on the intention to use mobile shopping applications. Technol. Soc. 2018, 53, 79–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Maghrabi, T.; Dennis, C.; Halliday, S.V. Antecedents of continuance intentions towards e-shopping: The case of Saudi Arabia. J. Enterp. Inf. Manag. 2011, 24, 85–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V.; Morris, M.G. Davis User Acceptance of Information Technology: Toward a Unified View. MIS Q. 2003, 27, 425–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kim, H.-W.; Chan, H.; Chan, Y.; Gupta, S. Understanding the Balanced Effects of Belief and Feeling on Information Systems Continuance. Proceedings of Understanding the Balanced Effects of Belief and Feeling on Information Systems Continuance, Washington, DC, USA, 12–15 December 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, N.; Srivastava, S.; Sinha, N. Consumer preference and satisfaction of M-wallets: A study on North Indian consumers. Int. J. Bank Mark. 2017, 35, 944–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fishbein, M.; Ajzen, I. Belief, Attitude, Intention, and Behavior: An Introduction to Theory and Research; Adison-Wesley: Reading, MA, USA, 1975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paige, S.R.; Bonnar, K.K.; Black, D.R.; Coster, D.C. Risk Factor Knowledge, Perceived Threat, and Protective Health Behaviors: Implications for Type 2 Diabetes Control in Rural Communities. Diabetes Educ. 2018, 44, 63–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenstock, I.M. Historical Origins of the Health Belief Model. Heal. Educ. Monogr. 1974, 2, 328–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaube, S.; Lermer, E.; Fischer, P. The Concept of Risk Perception in Health-Related Behavior Theory and Behavior Change. In Perceived Safety; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 101–118. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Y.; Ni, Q.; Zhou, R. What factors influence the mobile health service adoption? A meta-analysis and the moderating role of age. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2018, 43, 342–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dou, K.; Yu, P.; Deng, Z.; Liu, F.; Guan, Y.; Li, Z.; Ji, Y.; Du, N.; Lu, X.; Duan, H. Patients’ Acceptance of Smartphone Health Technology for Chronic Disease Management: A Theoretical Model and Empirical Test. JMIR mHealth uHealth 2017, 5, e177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychol. Rev. 1977, 84, 191–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Compeau, D.R.; Higgins, C.A. Computer Self-Efficacy: Development of a Measure and Initial Test. MIS Q. 1995, 19, 189–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- John, S.P. Influence of Computer Self-Efficacy on Information Technology Adoption. Int. J. Inf. Technol. 2013, 19, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Alfadda, H.A.; Mahdi, H.S. Measuring Students’ Use of Zoom Application in Language Course Based on the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM). J. Psycholinguist. Res. 2021, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.-H.; Wang, S.-C.; Lin, L.-M. Mobile computing acceptance factors in the healthcare industry: A structural equation model. Int. J. Med. Inform. 2007, 76, 66–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacherjee, A. An empirical analysis of the antecedents of electronic commerce service continuance. Decis. Support Syst. 2001, 32, 201–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Adlakaha, A.; Mukherjee, K. The effect of perceived security and grievance redressal on continuance intention to use M-wallets in a developing country. Int. J. Bank Mark. 2018, 36, 1170–1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleeby, J. Health Beliefs About Mental Illness: An Instrument Development Study. Am. J. Health Behav. 2000, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shmueli, G.; Sarstedt, M.; Hair, J.F.; Cheah, J.-H.; Ting, H.; Vaithilingam, S.; Ringle, C.M. Predictive model assessment in PLS-SEM: Guidelines for using PLSpredict. Eur. J. Mark. 2019, 53, 2322–2347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiau, W.-L.; Yuan, Y.; Pu, X.; Ray, S.; Chen, C.C. Understanding fintech continuance: Perspectives from self-efficacy and ECT-IS theories. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2020, 120, 1659–1689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, N.P. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 879–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Ardura, I.; Meseguer-Artola, A. Editorial: How to Prevent, Detect and Control Common Method Variance in Electronic Commerce Research. J. Theor. Appl. Electron. Commer. Res. 2020, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Maxwell, A.E.; Harman, H.H. Modern Factor Analysis. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. A 1968, 131, 615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kock, N. Common Method Bias in PLS-SEM. Int. J. e-Collab. 2015, 11, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chin, W.W. Issues and opinion on structural equation modeling. Mis Q. 1998, 22, vii–xvi. [Google Scholar]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sinkovics, R.R. The use of partial least squares path modeling in international marketing. In New Challenges to International Marketing; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2009; Volume 20, pp. 277–319. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error: Algebra and Statistics. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 382–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, D.T.; Fiske, D.W. Convergent and discriminant validation by the multitrait-multimethod matrix. Psychol. Bull. 1959, 56, 81–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2015, 43, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Akter, S.; D’Ambra, J.; Ray, P. An Evaluation of PLS Based Complex Models: The Roles of Power Analysis, Predictive Relevance and GoF Index. In Proceedings of the 17th Americas Conference on Information Systems, AMCIS 2011, Detroit, MI, USA, 4–8 August 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Risher, J.J.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M. When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. Eur. Bus. Rev. 2019, 31, 2–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, S.; Fangwei, Z.; Siddiqi, A.F.; Ali, Z.; Shabbir, M.S. Structural Equation Model for evaluating factors affecting quality of social infrastructure projects. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: NJ, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F., Jr.; Hult, G.T.M.; Ringle, C.; Sarstedt, M. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Equation Modelling (PLS-SEM); SAGE Publications Inc.: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, T.; Lin, C.-L.; Su, Y.-S. Continuance Intention of University Students and Online Learning during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Modified Expectation Confirmation Model Perspective. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, Y.; Hidayat-Ur-Rehman, I. COVID-19 crisis and the continuous use of virtual classes. Int. J. Adv. Appl. Sci. 2021, 8, 117–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palos-Sanchez, P.R.; Hernandez-Mogollon, J.M.; Campon-Cerro, A.M. The Behavioral Response to Location Based Services: An Examination of the Influence of Social and Environmental Benefits, and Privacy. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Susanto, A.; Chang, Y.; Ha, Y. Determinants of continuance intention to use the smartphone banking services. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2016, 116, 508–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heeks, R.; Ospina, A.V. Conceptualising the link between information systems and resilience: A developing country field study. Inf. Syst. J. 2019, 29, 70–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pal, A.; De’, R.; Herath, T. The Role of Mobile Payment Technology in Sustainable and Human-Centric Development: Evidence from the Post-Demonetization Period in India. Inf. Syst. Front. 2020, 22, 607–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afawubo, K.; Couchoro, M.K.; Agbaglah, M.; Gbandi, T. Mobile money adoption and households’ vulnerability to shocks: Evidence from Togo. Appl. Econ. 2020, 52, 1141–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theocharidis, A.-I.; Argyropoulou, M.; Karavasilis, G.; Vrana, V.; Kehris, E. An Approach towards Investigating Factors Affecting Intention to Book a Hotel Room through Social Media. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Construct | Definition | Sources |

|---|---|---|

| Confirmation/adoption (CF) | The user’s belief that actual performance when using a particular IT system meets expectations. | [28] |

| Perceived ease of use (PEU) | The user’s belief that using a particular IT system requires less effort. | [27,56] |

| Perceived usefulness (PU) | The users’ belief about how useful a particular IT system is for performing their job. | [27] |

| Satisfaction (SF) | A psychological or affective state related to and resulting from a cognitive evaluation of the discrepancy between expectancy and performance. | [28] |

| Attitude (ATT) | The favorable or unfavorable feelings that an individual develops to perform a particular behavior. | [67] |

| Perceived severity (P-SEV) | Beliefs about the degree of harm that will result from a negative outcome of a particular behavior. | [70] |

| Perceived susceptibility (P-SUS) | A person’s belief that they may acquire an adverse health outcome as a result of a particular behavior. | [70] |

| Self-efficacy (SE) | An individual’s belief that he or she is capable of successfully performing a particular behavior. | [73] |

| Continuous intention (CI) | An individual’s intention to use or reuse a particular system continuously. | [28] |

| Cronbach’s Alpha | (CR) | (AVE) | ATT | CF | CIN | P-SEV | P-SUS | PEU | PU | SE | SF | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ATT | 0.713 | 0.840 | 0.636 | 0.797 | ||||||||

| CF | 0.709 | 0.838 | 0.633 | 0.427 | 0.796 | |||||||

| CIN | 0.714 | 0.840 | 0.636 | 0.624 | 0.482 | 0.798 | ||||||

| P-SEV | 0.763 | 0.863 | 0.678 | 0.543 | 0.492 | 0.594 | 0.823 | |||||

| P-SUS | 0.727 | 0.845 | 0.646 | 0.384 | 0.507 | 0.393 | 0.434 | 0.804 | ||||

| PEU | 0.734 | 0.847 | 0.648 | 0.321 | 0.497 | 0.342 | 0.336 | 0.402 | 0.805 | |||

| PU | 0.734 | 0.848 | 0.650 | 0.551 | 0.624 | 0.609 | 0.579 | 0.545 | 0.536 | 0.806 | ||

| SE | 0.754 | 0.859 | 0.670 | 0.593 | 0.529 | 0.670 | 0.603 | 0.478 | 0.375 | 0.660 | 0.819 | |

| SF | 0.810 | 0.888 | 0.725 | 0.481 | 0.449 | 0.537 | 0.454 | 0.361 | 0.293 | 0.534 | 0.599 | 0.852 |

| Hypotheses | Original Sample (O) | Sample Mean (M) | Standard Deviation (STDEV) | T Statistics (|O/STDEV|) | p Values | Status | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1a | CF -> PU | 0.243 | 0.242 | 0.035 | 5.335 | 0.000 | Accepted |

| H1b | CF -> SF | 0.190 | 0.187 | 0.057 | 3.495 | 0.001 | Accepted |

| H2a | PEU -> PU | 0.228 | 0.229 | 0.035 | 6.401 | 0.000 | Accepted |

| H2b | PEU -> ATT | 0.034 | 0.033 | 0.042 | 0.762 | 0.425 | Rejected |

| H3a | PU -> SF | 0.416 | 0.417 | 0.046 | 8.904 | 0.000 | Accepted |

| H3b | PU -> ATT | 0.394 | 0.395 | 0.050 | 7.493 | 0.000 | Accepted |

| H3c | PU -> CIN | 0.187 | 0.186 | 0.044 | 4.182 | 0.000 | Accepted |

| H4a | SF -> ATT | 0.260 | 0.260 | 0.048 | 5.244 | 0.000 | Accepted |

| H4b | SF -> CIN | 0.115 | 0.115 | 0.037 | 2.999 | 0.002 | Accepted |

| H5 | ATT -> CIN | 0.281 | 0.285 | 0.041 | 6.746 | 0.000 | Accepted |

| H6a | P-SEV -> CF | 0.206 | 0.207 | 0.053 | 3.821 | 0.000 | Accepted |

| H6b | P-SEV -> PU | 0.178 | 0.180 | 0.046 | 3.446 | 0.000 | Accepted |

| H7a | P-SUS -> CF | 0.290 | 0.293 | 0.044 | 6.812 | 0.000 | Accepted |

| H7b | P-SUS -> PU | 0.139 | 0.140 | 0.038 | 3.654 | 0.000 | Accepted |

| H8a | SE -> CF | 0.266 | 0.262 | 0.054 | 4.923 | 0.000 | Accepted |

| H8b | SE -> PU | 0.339 | 0.338 | 0.041 | 7.795 | 0.000 | Accepted |

| H8c | SE -> PEU | 0.375 | 0.376 | 0.046 | 8.856 | 0.000 | Accepted |

| H8d | SE -> CIN | 0.310 | 0.308 | 0.048 | 5.843 | 0.000 | Accepted |

| Construct | R2 | Q2 | f2 | Decision |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Continuous intention | 0.559 | 0.351 | ||

| Attitude | 0.106 | Small | ||

| Satisfaction | 0.040 | Small | ||

| Perceived usefulness | 0.018 | Small | ||

| Self-efficacy | 0.096 | Small | ||

| Attitude | 0.353 | 0.220 | ||

| Satisfaction | 0.075 | Small | ||

| Perceived usefulness | 0.133 | Small | ||

| Perceived ease of use | 0.001 | Small | ||

| Satisfaction | 0.307 | 0.220 | ||

| Perceived usefulness | 0.152 | Medium | ||

| Confirmation | 0.032 | Small | ||

| Perceived usefulness | 0.613 | 0.389 | ||

| Perceived ease of use | 0.079 | Small | ||

| Confirmation | 0.062 | Small | ||

| Self-efficacy | 0.134 | Small | ||

| Perceived severity | 0.260 | 0.260 | 0.038 | Small |

| Perceived Susceptibility | 0.115 | 0.115 | 0.033 | Small |

| Confirmation | 0.388 | 0.240 | ||

| Self-efficacy | 0.067 | Small | ||

| Perceived severity | 0.043 | Small | ||

| Perceived Susceptibility | 0.100 | Small | ||

| Perceived ease of use | 0.141 | 0.085 | ||

| Self-efficacy | 0.164 | Medium |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Daragmeh, A.; Sági, J.; Zéman, Z. Continuous Intention to Use E-Wallet in the Context of the COVID-19 Pandemic: Integrating the Health Belief Model (HBM) and Technology Continuous Theory (TCT). J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2021, 7, 132. https://doi.org/10.3390/joitmc7020132

Daragmeh A, Sági J, Zéman Z. Continuous Intention to Use E-Wallet in the Context of the COVID-19 Pandemic: Integrating the Health Belief Model (HBM) and Technology Continuous Theory (TCT). Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity. 2021; 7(2):132. https://doi.org/10.3390/joitmc7020132

Chicago/Turabian StyleDaragmeh, Ahmad, Judit Sági, and Zoltán Zéman. 2021. "Continuous Intention to Use E-Wallet in the Context of the COVID-19 Pandemic: Integrating the Health Belief Model (HBM) and Technology Continuous Theory (TCT)" Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity 7, no. 2: 132. https://doi.org/10.3390/joitmc7020132

APA StyleDaragmeh, A., Sági, J., & Zéman, Z. (2021). Continuous Intention to Use E-Wallet in the Context of the COVID-19 Pandemic: Integrating the Health Belief Model (HBM) and Technology Continuous Theory (TCT). Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity, 7(2), 132. https://doi.org/10.3390/joitmc7020132