The Use of Trust Seals in European and Latin American Commercial Transactions

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Review of the Literature

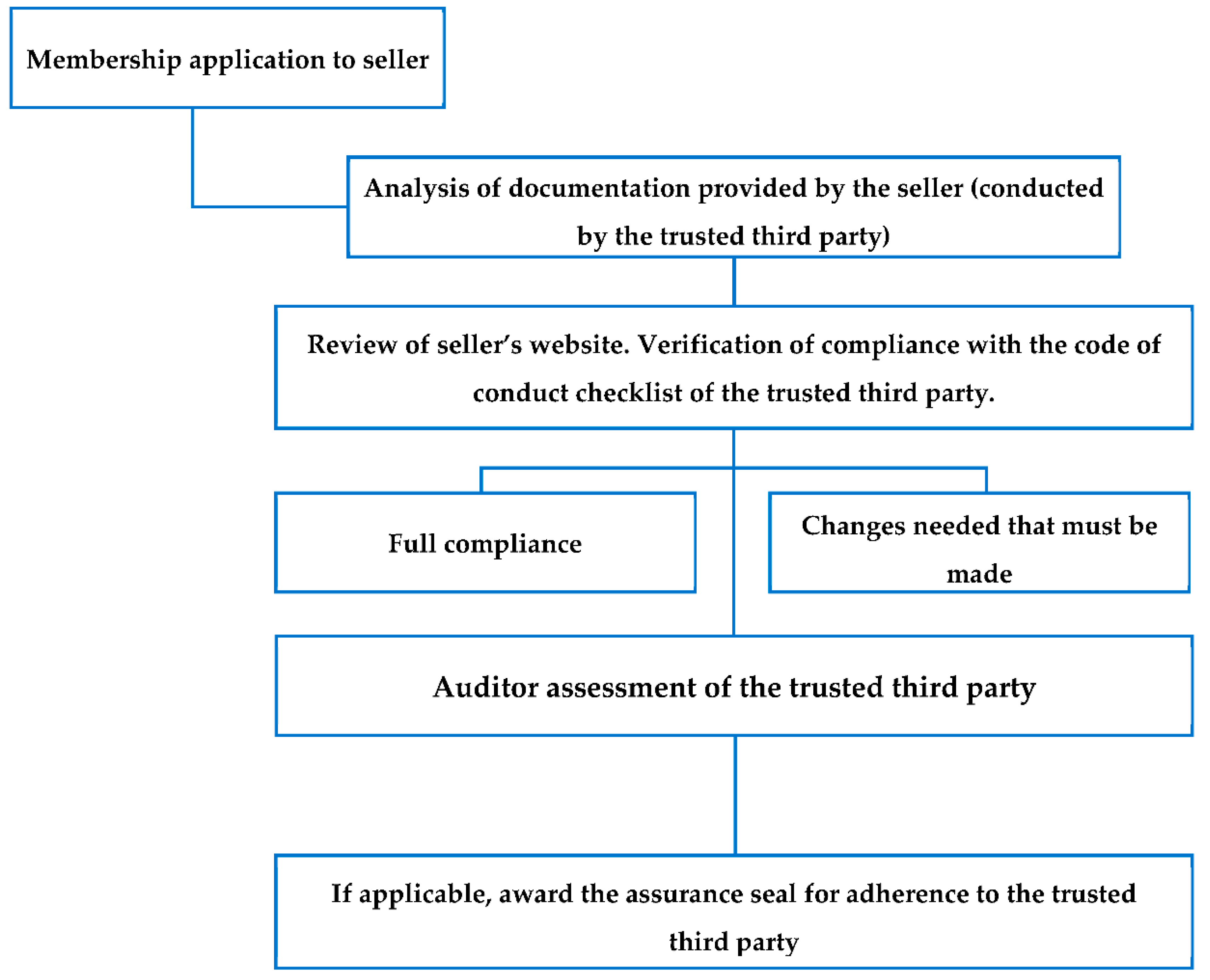

2.2. Phases of Adhering to an Assurance Seal

2.3. European and Latin American E-Commerce Self-Regulation Tools

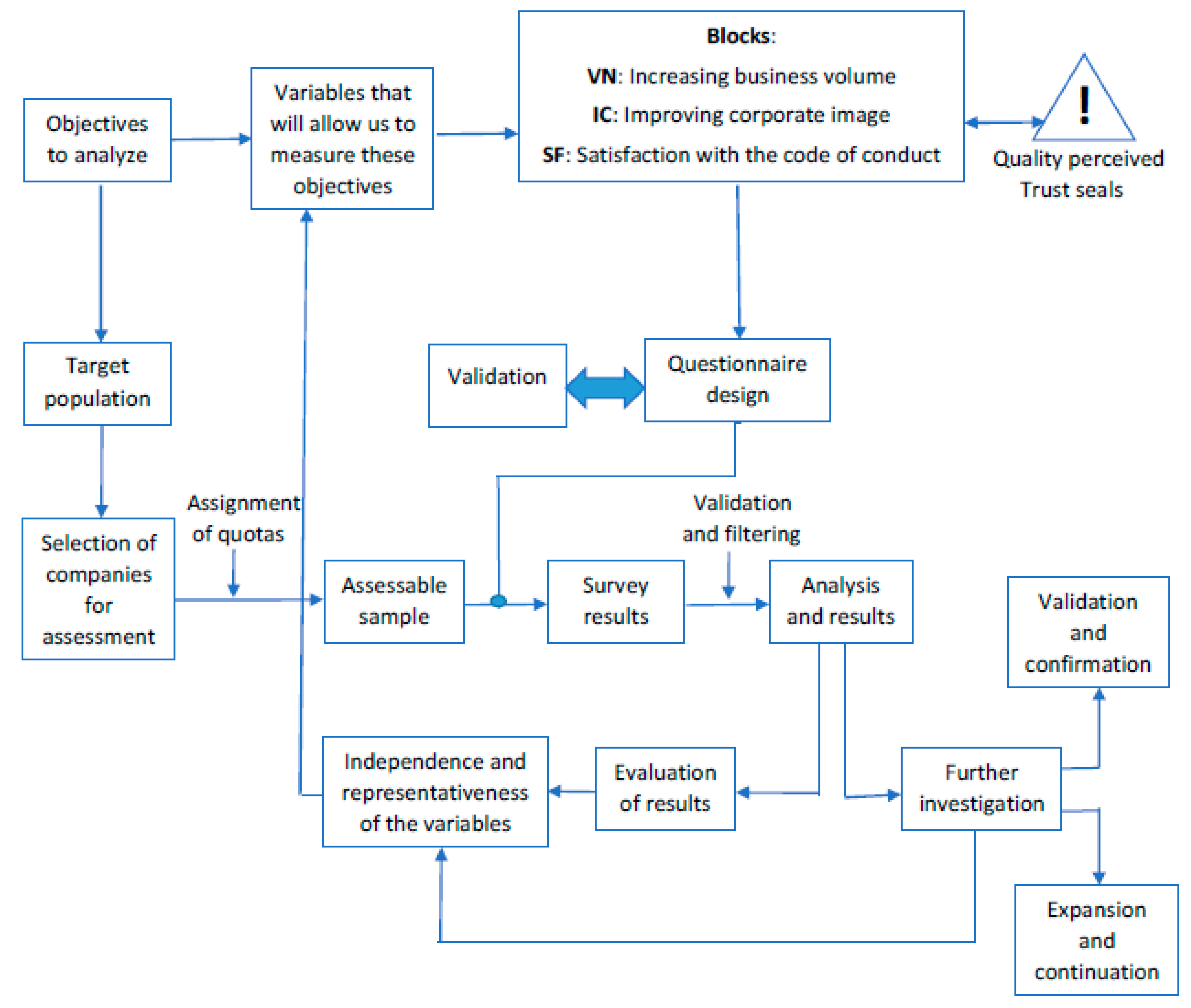

3. Empirical Method

4. Results

- The number of visits to the company’s website has greatly increased.

- The acquisition of new clients has increased.

- Internet sales have risen more than 66%.

- The companies state that the cost-benefit ratio in the adoption of a trust seal is very good. From a commercial point of view, they consider that improvements to their company’s image have been very positive.

5. Discussion: Managerial Implications and Open Innovation

- Improvement of corporate image;

- Higher transparency and traceability;

- Increase in perceived quality;

- Boost in Internet sales;

- Better positioning on the Internet and an effective presence;

- Increased visibility in the network;

- Differentiation from competition, both perceived and real.

6. Conclusions

7. Limitations and Future Lines of Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Brengman, M.; Karimov, F.P. The effect of web communities on consumers’ initial trust in B2C e-commerce websites. Manag. Res. Rev. 2012, 35, 791–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahmanziari, T.; Odom, M.D.; Ugrin, J.C. An experimental evaluation of the effects of internal and external e-Assurance on initial trust formation in B2C e-commerce. Int. J. Account. Inf. Syst. 2009, 10, 152–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallikainen, H.; Laukkanen, T. National culture and consumer trust in e-commerce. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2018, 38, 97–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKnight, D.H.; Lankton, N.K.; Nicolaou, A.; Price, J. Distinguishing the effects of B2B information quality, system quality, and service outcome quality on trust and distrust. J. Strateg. Inf. Syst. 2017, 26, 118–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donmaz, A. Privacy Policy and Security Issues in E-Commerce for Eliminating the Ethical Concerns. In Regulations and Applications of Ethics in Business Practice; Bian, J., Çalıyurt, K., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2018; pp. 153–164. [Google Scholar]

- Chiu, C.M.; Wang, E.T.G.; Fang, Y.H.; Huang, H.Y. Understanding customers’ repeat purchase intentions in B2C e-commerce: The roles of utilitarian value, hedonic value, and perceived risk. Inf. Syst. J. 2014, 24, 85–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Wu, G.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, H. The effects of Web assurance seals on consumers’ initial trust in an online vendor: A functional perspective. Decis. Support Syst. 2010, 48, 407–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, K. The penalty for privacy violations: How privacy violations impact trust online. J. Bus. Res. 2018, 82, 103–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moody, G.D.; Lowry, P.B.; Galletta, D.F. It’s complicated: Explaining the relationship between trust, distrust, and ambivalence in online transaction relationships using polynomial regression analysis and response surface analysis. Eur. J. Inf. Syst. 2015, 26, 379–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özpolat, K.; Jank, W. Getting the most out of third party trust seals: An empirical analysis. Decis. Support Syst. 2015, 73, 47–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Lim, E.-P. ReputationPro: The efficient approaches to contextual transaction trust computation in e-commerce environments. ACM Trans. Web 2015, 9, 2–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rampton, J. Importance of a Trust Seal on Your eCommerce Website. Forbes Tech. 2014. Available online: https://www.forbes.com/sites/johnrampton/2014/12/16/importance-of-a-trust-seal-on-your-ecommerce-website/#67813b7e6802 (accessed on 2 January 2021).

- Jaiswala, A.K.; Nirajb, R.; Parkc, C.H.; Agarwal, M.K. The effect of relationship and transactional characteristics on customer retention in emerging online markets. J. Bus. Res. 2018, 92, 25–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doney, P.M.; Cannon, J.P. An examination of the nature of trust in buyer-seller relationships. J. Mark. 1997, 61, 35–51. [Google Scholar]

- Teo, T.S.; Liu, J. Consumer trust in e-commerce in the United States. Singapore, and China. Omega 2007, 35, 22–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.; Nazareth, D.L. Repairing trust in an ecommerce and security context: An agent-based modeling approach. Inf. Manag. Comput. Secur. 2014, 22, 490–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.J.; Ferrin, D.L.; Rao, H.R. A trust-based consumer decision-making model in electronic commerce: The role of trust. perceived risk, and their antecedents. Decis. Support Syst. 2008, 44, 544–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, A.; Monroe, K. The effect of price, brand name, and store name on buyers’ perceptions of product quality: An integrative review. J. Mark. Res. 1989, 26, 351–357. [Google Scholar]

- Barkatullah, A.H.; Djumadi, A. Does self-regulation provide legal protection and security to e-commerce consumers? Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2018, 30, 94–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauman, A.; Bachmann, R. Online Consumer Trust: Trends in Research. J. Technol. Manag. Innov. 2017, 12, 68–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín-Romo Romero, S.; De Pablos Heredero, C. Data protection by design: Organizational integration. Harv. Deusto Bus. Res. 2018, 7, 60–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.J.; Yim, M.S.; Sugumaran, V.; Rao, H.R. Web assurance seal services, trust, and consumers’ concerns: An investigation of e-commerce transaction intentions across two nations. Eur. J. Inf. Syst. 2016, 25, 252–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López Jiménez, D.; Vargas Portillo, J.P.; Dittmar, E.C. Safeguarding Privacy in Social Networks. Law State Telecommun. Rev. 2020, 12, 58–76. [Google Scholar]

- Qu, M.; Kim, J.; Choi, S. The effects of multidimensional customer trust on purchase and eWOM intentions in social commerce based on WeChat in China. Asia Pac. J. Inf. Syst. 2017, 27, 77–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seckler, M.; Heinz, S.; Forde, S.; Tuch, A.N.; Opwis, K. Trust and distrust on the web: User experiences and website characteristics. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2015, 45, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stouthuysen, K.; Teunis, L.; Reusen, E.; Slabbinck, H. Initial trust and intentions to buy: The effect of vendorspecific guarantees, customer reviews, and the role of online shopping experience. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2018, 27, 23–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKnight, D.H.; Kacmar, C.; Choudhary, V. Shifting Factors and the Ineffectiveness of Third Party Assurance Seals: A Two-Stage Model of Initial Trust in an E-Vendor. Electron. Mark. 2004, 14, 252–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danidou, Y.; Schafer, B.B. Legal environments for digital trust: Trustmarks, trusted computing, and the issue of legal liability. J. Int. Commer. Law Technol. 2012, 7, 212–222. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, F.M.; Tuzovic, S.; Braun, C. Trustmarks: Strategies for exploiting their full potential in ecommerce. Bus. Horiz. 2019, 62, 237–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wareham, J.; Zheng, J.G.; Straub, D. Critical themes in electronic commerce research: A meta-analysis. J. Inf. Technol. 2005, 20, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.C.; Chen, C.C. Electronic Commerce Research in Latest Decade: A Literature Review. Int. J. Electron. Commer. Stud. 2010, 1, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Wirtz, B.W.; Schilke, O.; Ullrich, S. Strategic development of business models: Implications of the Web 2.0 for creating value on the Internet. Long Range Plan. 2010, 43, 272–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, R.; Pucihar, A. Electronic interaction research 1988–2012 through the lens of the Bled eConference. Electron. Mark. 2013, 23, 271–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, R.; Hunt, S. The Commitment-Trust Theory of Relationship Marketing. J. Mark. 1994, 58, 20–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balboni, P.; Dragan, T. Controversies and Challenges of Trustmarks: Lessons for Privacy and Data Protection Seals. In Privacy and Data Protection Seals; Rodrigues, R., Papakonstantinou, V., Eds.; T.M.C. Asser Press: The Hague, The Netherlands, 2018; pp. 83–111. [Google Scholar]

- McKnight, D.H.; Chervany, N.L. What Trust means in E-Commerce Customer Relationships: An Interdisciplinary Conceptual Typology. Int. J. Electron. Commer. 2001, 6, 35–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, I.B.; Cha, H.S. The mediating role of consumer trust in an online merchant in predicting purchase intention. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2013, 33, 927–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López Jiménez, D.; Dittmar, E.C.; Vargas Portillo, J.P. Self-regulation of Sexist Digital Advertising: From Ethics to Law. J. Bus. Ethics 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puente Domínguez, N. Case study analyzing the relationship between the degree of complexity of a product page on an e-commerce website and the number of unique purchases associated with it. Harv. Deusto Bus. Res. 2019, 8, 229–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, L.; Du, J.; Zhang, J.; Pan, Y. The trusted online platform of cross-border e-commerce: A managerial model. In Proceedings of the IEEE 3rd Information Technology, Networking, Electronic and Automation Control Conference (ITNEC), Chengdu, China, 15–17 March 2019; pp. 827–830. [Google Scholar]

- Lachaud, E. The General Data Protection Regulation and the rise of certification as a regulatory instrument. Comput. Law Secur. Rev. 2018, 34, 244–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangold, W.G.; Faulds, D.J. Social media: The new hybrid element of the promotion mix. Bus. Horiz. 2009, 52, 357–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimery, M.K.; McCord, M. Signals of Trustworthiness in e-commerce: Consumer Understanding of Third Party Assurance Seals. J. Electron. Commer. Organ. 2006, 4, 52–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riegelsberger, J.; Sasse, M.A. Trustbuilders and Trustbusters. In Towards the E-Society; Schmid, B., Stanoevska-Slabeva, K., Tschammer, V., Eds.; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2001; pp. 17–30. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, C.; Mattison Thompson, F.; Grimm, P.E.; Robson, K. Pre-roll advertising: The impact of emotion, feeling, and objective ad characteristics on consumer skipping. J. Advert. 2017, 46, 411–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivascanu, D. Legal issues in electronic commerce in the western hemisphere. Ariz. J. Int. Comp. Law 2000, 17, 219–221. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, S.; Ahn, C.; Song, K.; Ahn, H. Trust and Distrust in E-Commerce. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, B.; Zeng, Q.; Fan, W. Examining macro-sources of institution-based trust in social commerce marketplaces: An empirical study. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2016, 20, 116–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimov, F.P.; Brengman, M. An examination of trust assurances adopted by top internet retailers: Unveiling some critical determinants. Electron. Commer. Res. 2014, 14, 459–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Lin, Z.; Zhang, H. Trust promoting seals in electronics markets: An Exploratory Study of Their Effectiveness for Online Sales Promotion. J. Promot. Manag. 2002, 9, 163–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mauldin, E.; Arunachalam, V. An experimental examination of alternative forms of Web assurance for Business-to-Consumer eCommerce. J. Inf. Syst. 2002, 16, 33–54. [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan, Y.W.; Kim, D.J. Assessing the effects of consumers’ product evaluations and trust on repurchase intention in e-commerce environments. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2018, 39, 199–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikitkov, A. Information assurance seals: How they Impact Consumer Purchasing Behavior. J. Inf. Syst. 2006, 20, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lala, V.; Arnold, V.; Sutton, S.G.; Guan, L. The impact of relative information quality of e-commerce assurance seals on Internet purchasing behavior. Int. J. Account. Inf. Syst. 2002, 3, 237–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grazioli, S.; Jarvenpaa, S.L. Perils of Internet fraud: An empirical investigation of deception and trust with experienced Internet consumers. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. Part A Syst. Hum. 1997, 30, 395–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovar, S.E.; Burke, K.G.; Kovar, B.R. Consumer Responses to the CPA WEBTRUST™ Assurance. J. Inf. Syst. 2000, 14, 17–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portz, K.; Strong, J.M.; Sundby, L. To trust or not to trust: The impact of Webtrust on the perceived trustworthiness of a website. Rev. Bus. Inf. Syst. 2001, 5, 35–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Miyasaki, A.D.; Krishnamurthy, S. Internet seals of approval: Effects on online privacy policies and consumer perceptions. J. Consum. Aff. 2002, 36, 28–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, S.E.; Nieschwietz, R.J. An Examination of the Effects of WebTrust and Company Type on Consumers’ Purchase Intentions. Int. J. Audit. 2003, 7, 155–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Beatty, S.E.; Foxx, W. Signaling the trustworthiness of small online retailers. J. Interact. Mark. 2004, 18, 53–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rifon, N.F.; Larose, R.; Choi, S.M. Your Privacy Is Sealed: Effects of Web Privacy Seals on Trust and Personal Disclosures. J. Consum. Aff. 2005, 39, 339–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H. Trust-promoting seals in electronic markets: Impact on online shopping decisions. J. Inf. Technol. Theory Appl. 2005, 6, 29–40. [Google Scholar]

- Metzger, M.J. Effects of Site, Vendor, and Consumer Characteristics on Web Site Trust and Disclosure. Commun. Res. 2006, 33, 155–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitten, D.; Wakefield, R.L. Measuring switching costs in IT outsourcing services. J. Strateg. Inf. Syst. 2006, 15, 219–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, P.; Jones, D.B.; Javie, S. How third-party certification programs relate to consumer trust in online transactions: An exploratory study. Psychol. Mark. 2008, 25, 839–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.; Kim, J. Third-party privacy certification as an online advertising strategy: An investigation of the factors affecting the relationship between third-party certification and initial trust. J. Interact. Mark. 2011, 25, 145–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mascha, M.F.; Miller, C.L.; Janvrin, D.J. The effect of encryption on Internet purchase intent in multiple vendor and product risk settings. Electron. Commer. Res. 2011, 11, 401–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Utz, S.; Kerkhof, P.; Van Den Bos, J. Consumers rule: How consumer reviews influence perceived trustworthiness of online stores. Electron. Commer. Res. Appl. 2012, 11, 49–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özpolat, K.; Gao, G.; Jank, W.; Viswanathan, S. The value of third-party assurance seals in online retailing: An empirical investigation. Inf. Syst. Res. 2013, 24, 1100–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Jiang, J.; Wu, M. The effects of trust assurances on consumers’ initial online trust: A two-stage decision-making process perspective. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2014, 34, 395–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J. Dual effect of price in e-commerce environment: Focusing on trust and distrust building processes. Asia Pac. J. Inf. Syst. 2014, 24, 393–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pineda-Albaladejo, J.M.; Moya-Faz, F.J.; Puga, J.L. Training in Values as an Incubator for Sustainability Attitudes. Harv. Deusto Bus. Res. 2017, 6, 133–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sposato, M.; Rumens, N. Advancing international human resource management scholarship on paternalistic leadership and gender: The contribution of postcolonial feminism. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2021, 32, 1201–1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López Jiménez, D.; Redchuk, A.; Dittmar, E.C.; Vargas Portillo, J.P. Los logotipos de privacidad en Internet: Percepción del usuario en España. RISTI-Rev. Ibérica Sist. Tecnol. Inf. 2013, 12, 49–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Sposato, M.; Jeffrey, H.L. Inside-Out Interviews: Cross-Cultural Research in China. Manag. Organ. Rev. 2020, 16, 445–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martens, B. An Economic Policy Perspective on Online Platforms. JRC Working Papers on Digital Economy. 2016. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/jrc/en/publication/eur-scientific-and-technical-research-reports/economic-policy-perspective-online-platforms (accessed on 2 January 2021).

- López Jiménez, D.; Dittmar, E.C.; Vargas Portillo, J.P. New Directions in Corporate Social Responsibility and Ethics: Codes of Conduct in the Digital Environment. J. Bus. Ethics 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abedi, F.; Zeleznikow, J.; Brien, C. Developing regulatory standards for the concept of security in online dispute resolution systems. Comput. Law Secur. Rev. 2019, 35, 105328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Authors | Objective | Collective | Seals | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grazioli & Jarvenpaa (2000) [55] | Deceptive e-commerce | Students | BBBOnLine | Trust seals affect a buyer’s perceived risk. The study focuses on the importance of buyer education. |

| Kovar, Gladden & Kovar (2000) [56] | Simulated e-commerce | Students | Webtrust | Buyers who pay more attention to a seal on a seller’s website or who have viewed WebTrust advertising have higher transaction expectations than their counterparts. |

| Portz, Strong & Sundby (2000) [57] | Simulated e-commerce | Students | Webtrust | Trust seals in general, and Webtrust in particular, have a significant impact on transactions carried out on the Internet. |

| Hu, Lin & Zhang (2002) [50] | Simulated e-commerce | Students | BBBOnLine Verisign TRUSTe | There is an overall positive effect on purchase intention for AOL, BBBOnLine and Verisign. There is no global effect for Verisign or TRUSTe. Effects for TRUSTe and Verisign vary by product category. |

| Lala, Arnold, Sutton, & Guan (2002) [54] | Online Travel Agencies | Students | BBBOnLine Webtrust | There is no effect on purchase intention for BBB Online and a positive effect for Webtrust. |

| Mauldin & Arunachalam (2002) [51] | Real e-commerce | Students | TRUSTe Webtrust | There is no overall effect on purchase intention. There are no differences between seals. |

| Miyasaki & Krishnamurthy (2002) [58] | Simulated e-commerce | Students | BBBOnLine TRUSTe | Seals have an overall positive effect on purchase intention when there is a high purchase risk. There is no effect when the purchase risk is low. |

| Kaplan & Nieschwietz (2003) [59] | Simulated e-commerce | Students | BBBOnLine TRUSTe Webtrust | There is a positive effect of security on trust, which influences purchase intention. |

| McKnight, Choudhary & Kacmar (2004) [27] | Simulated e-commerce, Legal Advice | Students | TRUSTe | The TRUSTe seal is imperceptible, and the seals of professional associations do not have a significant impact on buyer confidence. |

| Wang, Beatty & Foxx (2004) [60] | Simulated e-commerce | Students | BBBOnLine TRUSTe Verisign | A guarantee seal does not increase the confidence of buyers. |

| Rifon, Larose & Choi (2005) [61] | Simulated e-commerce | Students | TRUSTe BBBOnLine | Privacy seals increase trust in a website and the expectation that the website will inform a buyer of its information practices. |

| Zhang (2005) [62] | Simulated e-commerce | Students | TRUSTe. Verisign BBBOnLine | Trust seals affect buyers and, to a great extent, the possibility of carrying out a transaction. |

| Kimery & McCord (2006) [43] | Home Furniture | Students | TRUSTe. Verisign BBBOnLine | There is no significant relationship between guarantee seals and buyers’ confidence. |

| Metzger (2006) [63] | Real (Music) and Simulated e-commerce | Students | TRUSTe | Little-known trust seals have no impact on a potential buyer. |

| Nikitkov (2006) [53] | Online Auctions | eBay users | Square Trade Power Seller | The Square Trade seal has an impact on the confidence that buyers show towards sellers on eBay. |

| Whitten & Wakefield (2006) [64] | Simulated e-commerce | Students | BBBOnLine TRUSTe Verisign Webtrust | Trusted third-party credibility positively affects purchase intention due to seal value, perceived risk, and trust. |

| Jiang, Jones & Javie (2008) [65] | Real e-commerce | Shoppers | BBBOnLine TRUSTe Verisign | Seals have an overall positive effect on trust. The specific effect varies according to the seal mode. |

| Bahmanziari, Odom & Ugrin (2009) [2] | Simulated e-commerce | Students | Verisign Webtrust | There is no relationship between trust and purchase intention for Webtrust. However, the combination of seals has a positive effect. |

| Hu, Wu, Wu & Zhang (2010) [7] | Simulated e-commerce | Students | Cybertrust | Seals have a positive impact on buyer confidence. |

| Kim & Kim (2011) [66] | Simulated e-commerce | Students | TRUSTe | Seals have positive effects on buyer confidence. |

| Mascha, Miller & Janvrin (2011) [67] | Simulated e-commerce | Students | Invented seal “Web Honesty” | Seals have positive effects on purchase intention. They are similar to encryption. |

| Utz, Kerkhof & Van Den Bos (2012) [68] | iPod Nano | Shoppers | Qshops Keurmerk Thuiswinkel Waarborg Webshop Keurmerk | Seals have no significant impact on trust. |

| Özpolat, Gao, Jank & Viswanathan (2013) [69] | Health Care Products | Shoppers | Buysafe | Seals have a positive impact on purchase intention when they are known by their recipients. |

| Li, Jiang & Wu (2014) [70] | Simulated e-commerce | Students | Webtrust | Trust seals have a positive influence on electronic transactions. |

| Bauman & Bachman (2017) [20] | Simulated e-commerce | Students | TRUSTe | Seals have no significant impact on trust. |

| Barkatullah & Djumadi (2018) [19] | Real e-commerce | Shoppers | BBBOnLine Verisign TRUSTe | Seals have a positive impact on purchase intention. |

| Country | Regulatory Body | Website |

|---|---|---|

| Germany | EHI Geprüfter Online Shop | www.ehi-siegel.de (accessed on 2 January 2021). |

| Haendlerbund | www.haendlerbund.de (accessed on 2 January 2021). | |

| Internet Privacy Standards | www.datenschutz-nord-gruppe.de (accessed on 2 January 2021). | |

| Safer Shopping | www.tuvsud.com/de-de/dienstleistungen/cyber-security/online-guetesiegel-safer-shopping (accessed on 2 January 2021). | |

| Shoplupe | www.shoplupe.com (accessed on 2 January 2021). | |

| Austria | Trustmark Austria | www.handelsverband.at/trustmark/trustmark-austria/ (accessed on 6 January 2021). |

| Österreichisches E-commerce-Gütezeichen | www.guetezeichen.at (accessed on 6 January 2021). | |

| Belgium | Becommerce label | www.becommerce.be (accessed on 9 January 2021). |

| Safeshops.be | www.safeshops.be (accessed on 1 January 2021). | |

| Unizo | www.unizo.be (accessed on 7 January 2021). | |

| Croatia | Shopper’s Mind | www.smind.hr (accessed on 4 January 2021). |

| Denmark | E-market | www.emaerket.dk (accessed on 5 January 2021). |

| Slovenia | Shopper’s Mind | www.smind.si (accessed on 3 January 2021). |

| Spain | Aenor | www.aenor.com (accessed on 9 January 2021). |

| Confianza Online | www.confianzaonline.es (accessed on 9 January 2021). | |

| Calidad Online | www.calidadonline.es (accessed on 9 January 2021). | |

| Icert | www.icert.es (accessed on 4 January 2021). | |

| Evalor | www.evalor.es (accessed on 2 January 2021). | |

| Estonia | Eesti E-kaubanduse Liit | www.e-kaubanduseliit.ee (accessed on 2 January 2021). |

| Finland | ASML | www.asml.fi (accessed on 1 January 2021). |

| France | Fevad | www.fevad.com (accessed on 8 January 2021). |

| Greece | Epam | www.enepam.gr (accessed on 7 January 2021). |

| GRECA Trustmark | www.trustmark.gr (accessed on 4 January 2021). | |

| Netherlands | Webshop Keurmerk | www.keurmerk.info/en/home (accessed on 2 January 2021). |

| WebwinkelKeur | www.webwinkelkeur.nl (accessed on 12 January 2021). | |

| Thuiswinkel | www.thuiswinkel.org (accessed on 12 January 2021). | |

| Hungary | eQ-recommendation | www.ivsz.hu (accessed on 12 January 2021). |

| Ireland | EIQA W-Mark | www.eiqa.i.e., (accessed on 4 January 2021). |

| Retail Excellence | www.retailexcellence.i.e., (accessed on 2 January 2021). | |

| Italy | QCB Italia | www.qcb.it (accessed on 9 January 2021). |

| QWEB | www.qweb.eu/it (accessed on 9 January 2021). | |

| Netcomm | www.consorzionetcomm.it/sigillo (accessed on 9 January 2021). | |

| Norway | Trygg E-handel | www.tryggehandel.no (accessed on 5 January 2021). |

| Czech Republic | Apek | www.apek.cz (accessed on 6 January 2021). |

| Portugal | CONFIO | www.confio.pt (accessed on 5 January 2021). |

| United Kingdom | SafeBuy | www.safebuy.org.uk (accessed on 14 January 2021). |

| Sectigo | www.sectigo.com (accessed on 14 January 2021). | |

| TrustMark | www.trustmark.org.uk (accessed on 14 January 2021). | |

| Sweden | Trygg E-handel | www.dhandel.se/trygg-e-handel (accessed on 13 January 2021). |

| Switzerland | Swiss Online Garantie | www.vsv-versandhandel.ch/consumer/swiss-online-garantie (accessed on 15 January 2021). |

| Brazil | Movimiento e-MPE | www.e-mpe.com (accessed on 16 January 2021). |

| Chile | Confianza Ecommerce CCS | www.ecommerceccs.cl/sello-confianza-ecommerce-ccs/ (accessed on 17 January 2021). |

| Mexico | Asociación de Internet MX | www.sellosdeconfianza.org.mx (accessed on 2 January 2021). |

| Peru | Capece | www.capece.org.pe (accessed on 18 January 2021). |

| Guatemala | GRECOM | www.grecom.gt (accessed on 18 January 2021). |

| Latin America | EConfianza | www.ecommerce.institute/econfianza (accessed on 20 January 2021). |

| Group | Questions |

|---|---|

| Introductory | IN1—Can you tell us how you learned about the code of conduct? |

| IN2—Why did you decide to adhere to the e-commerce code of conduct? | |

| IN3—Do you support the existence of numerous e-commerce codes of conduct, or do you wish there were only one? | |

| IN4—Do you see a future for the code of conduct? | |

| Increasing business volume | VN1—From your perspective, rate how much adherence has increased visits to your website. |

| VN2—Rate your increase in new clients since adhering to the code of conduct. | |

| VN3—Did the improvements you had to make to adhere to the code of conduct positively influence you from a business perspective? | |

| VN4—Has adherence resulted in increased online sales? | |

| Improving corporate image | IC1—Do you think your corporate image has improved? |

| IC2—Do you think customers’ quality-price perception has improved since your adherence? | |

| Satisfaction with the code of conduct | SF1—Have you ever thought about switching codes of conduct? |

| SF2—Do you think that the code of conduct you are adhering to should be improved? | |

| SF3—Rate the promoting organization’s work in extrajudicial conflict resolution processes. | |

| SF4—Rate the solutions adopted in the event of conflict by the relevant promoting organization. | |

| SF5—Evaluate the degree to which adherence has met and continues to meet your expectations. | |

| SF6—Rate the management capabilities of the organization responsible for the code of conduct you adhere to. |

| Question | Scale | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| IN1 | Open question | - | |

| IN2 | Open question | - | |

| IN3 | Only one code | Many codes | |

| IN4 | Open question | - | |

| VN1 | To a low degree | To a medium degree | To a high degree |

| VN2 | To a low degree | To a medium degree | To a high degree |

| VN3 | Negatively | Positively | Very positively |

| VN4 | 0–33% | 33–66% | >66% |

| IC1 | To a low degree | To a medium degree | To a high degree |

| IC2 | Low ratio | Medium ratio | High ratio |

| SF1 | No | Yes | |

| SF2 | No | Yes | |

| SF3 | No | Yes | |

| SF4 | Inappropriate | Appropriate | Very appropriate |

| SF5 | No | Yes | |

| SF6 | Negative | Positive | Very Positive |

| # | Question | % |

|---|---|---|

| IN3 | Are you in favor of numerous codes of conduct for e-commerce, or do you wish there were only one? | Only one: 95.28% |

| SF1 | Have you ever considered changing your code of conduct? | No: 96.85% |

| SF2 | Do you think that the code of conduct you are adhering to should be improved? | No: 82.68% |

| SF3 | In case you have had to appeal to the extrajudicial conflict resolution procedure: Do you consider the work of the extrajudicial conflict resolution mechanism to be positive in general? | Yes: 66.67% |

| SF5 | Did the membership meet and still meet your expectations? | Yes: 79.53% |

| # | Question | Mean (SD) |

|---|---|---|

| VN1 | To what extent do you understand that adherence to the code of conduct has increased visits to your website? | To a high degree (2.47) 0.60 |

| VN2 | How do you think that the acquisition of new customers has increased? | To a high degree (2.44) 0.57 |

| VN3 | How do you rate, from a commercial point of view, the improvement you had to make? | Very positively (2.37) 0.50 |

| VN4 | How do you understand that your Internet sales have increased? | More than 66% (2.93) 0.32 |

| IC1 | How do you think your corporate image has improved? | To a medium degree (1.89) 0.74 |

| IC2 | To what degree is there a quality-price correlation? | High degree (2.33) 0.74 |

| SF4 | How would you assess the solution finally adopted? | Appropriate (2.33) 0.52 |

| SF6 | How do you rate the management operated by the entity responsible for the code of conduct to which you adhere? | Positive (1.84) 0.72 |

| # | Question | 97% Confidence Intervals | |

|---|---|---|---|

| VN1 | To what extent do you understand that adherence to the code of conduct has increased visits to your website? | (2.35–2.59) | To a high degree |

| VN2 | How do you think that the acquisition of new customers has increased? | (2.33–2.55) | To a high degree |

| VN3 | How do you rate, from a commercial point of view, the improvement you had to make? | (2.27–2.47) | Very positively |

| VN4 | How much do you think your Internet sales have increased? | (2.87–2.99) | More than 66% |

| IC1 | How do you think your corporate image has improved? | (1.75–2.03) | To a medium degree |

| IC2 | How strong is the quality-price correlation? | (2.19–2.47) | Medium-high corelation |

| SF4 | How would you assess the solution finally adopted? | (1.87–2.79) | Appropriate–very appropriate |

| SF6 | How do you rate the management operated by the entity responsible for the code of conduct to which you adhere? | (1.67–1.95) | Positively |

| IN3 | Are you in favor of numerous codes of conduct for e-commerce, or do you wish there were only one? | Only one: | (93–97%) |

| SF1 | Have you ever considered changing your code of conduct? | Yes: | (0–3%) |

| SF2 | Do you think that the code of conduct to which you adhere should be improved? | Yes: | (14–21%) |

| SF3 | In case you have had to appeal to the extrajudicial conflict resolution procedure: Do you consider the work of the extrajudicial conflict resolution mechanism to be positive in general? | Yes: | (47–86%) |

| SF5 | Did the membership meet and does it still meet your expectations? | Yes: | (76–83%) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

López Jiménez, D.; Dittmar, E.C.; Vargas Portillo, J.P. The Use of Trust Seals in European and Latin American Commercial Transactions. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2021, 7, 150. https://doi.org/10.3390/joitmc7020150

López Jiménez D, Dittmar EC, Vargas Portillo JP. The Use of Trust Seals in European and Latin American Commercial Transactions. Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity. 2021; 7(2):150. https://doi.org/10.3390/joitmc7020150

Chicago/Turabian StyleLópez Jiménez, David, Eduardo Carlos Dittmar, and Jenny Patricia Vargas Portillo. 2021. "The Use of Trust Seals in European and Latin American Commercial Transactions" Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity 7, no. 2: 150. https://doi.org/10.3390/joitmc7020150

APA StyleLópez Jiménez, D., Dittmar, E. C., & Vargas Portillo, J. P. (2021). The Use of Trust Seals in European and Latin American Commercial Transactions. Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity, 7(2), 150. https://doi.org/10.3390/joitmc7020150