Corporate Glocalization Strategy of Nongshim in America: The “Pendulum Theory” of Globalized Localization

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Globalization, Localization and Glocalization

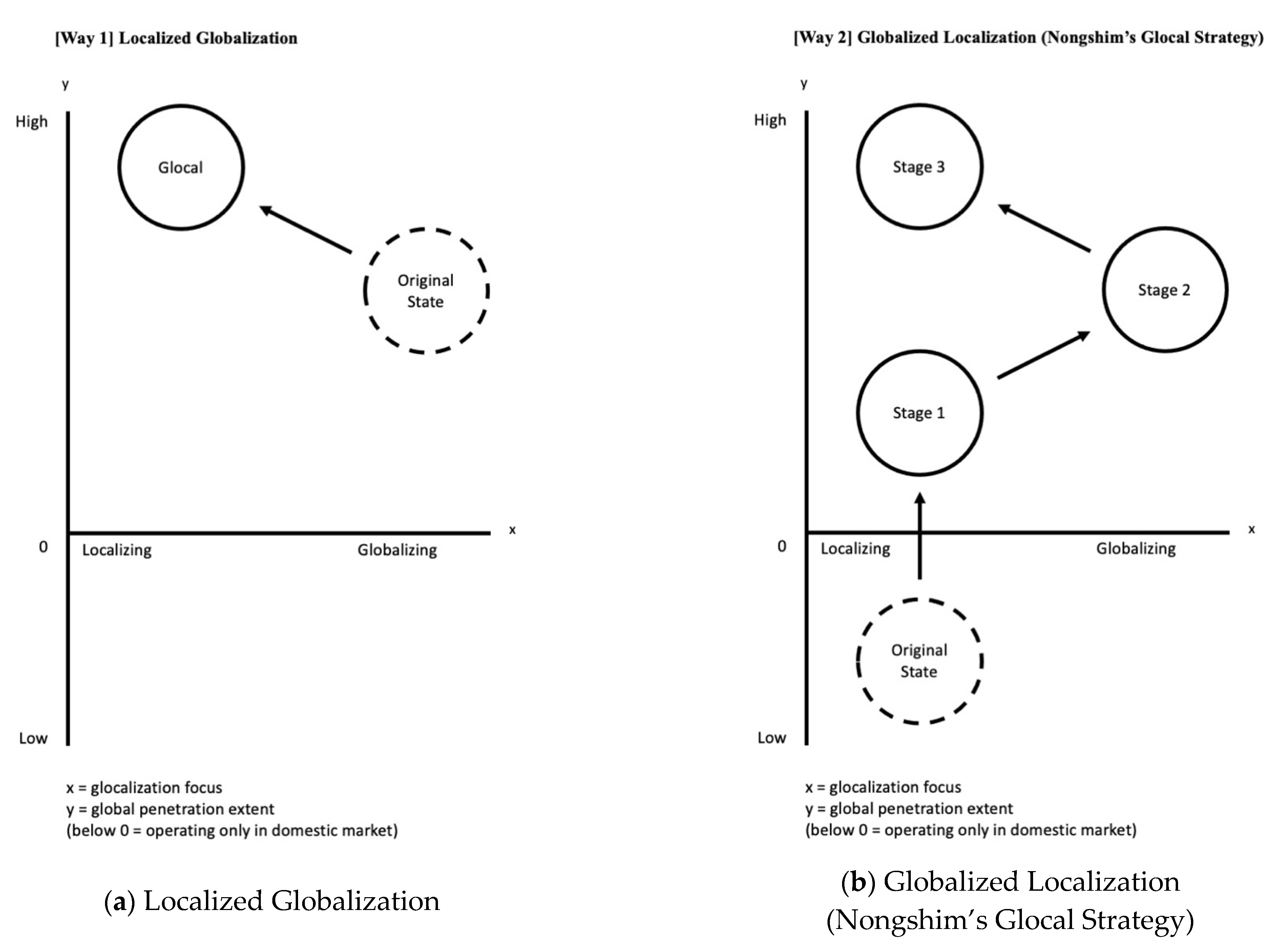

2.2. Approaches to Glocalization

3. Methodology

Data Collection and Data Analysis

4. Nongshim’s Glocalization in the U.S.

5. Nongshim Company Background

6. Nongshim in the US Market

6.1. US Instant Noodle Market: Size and Current Situation

6.2. U.S. Competitor Analysis

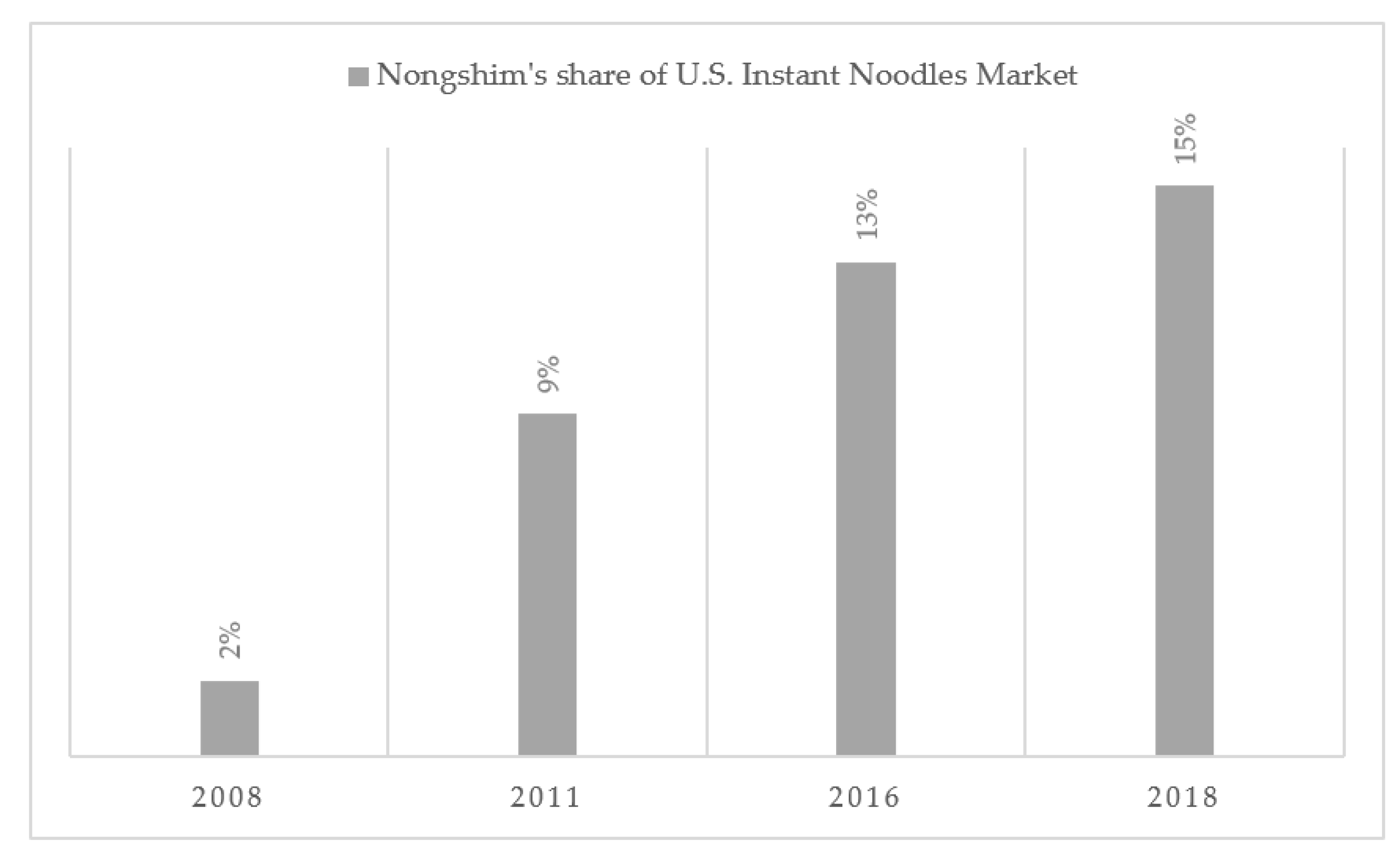

6.3. Success Story of Nongshim

6.3.1. Core Competency of Nongshim: R&D Ability

6.3.2. Success Strategy of Nongshim

- Product Differentiation Strategy (Positioning Premium)

- Promotion Strategy

- Accessing Mainstream Distribution Channels and Step-by-Step Strategy

- Brand Power Improvement

7. Nongshim’s Glocal Strategy

7.1. Pendulum Theory: A Theoretical Framework for Corporate Glocalization

- Stage 1: Localization

- Stage 2: Globalization

- Stage 3: Re-Localization

7.2. Reasoning behind the Re-Localization

8. Discussion

8.1. Theoretical and Practical Implications

8.2. Glocalization as Open Innovation

9. Conclusions

9.1. Findings

9.2. Limitations and Future Research Topics

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

References

- Shin, K.S. Adaptive Framework for Designing R&D Project Management Process Using Cloud Computing Technology. Soc. E-Bus. Stud. 2013, 18, 25–43. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, H.J. Glocalization Strategy of Coca-Cola: Did it reflect the local markets? Glocal Creat. Ind. Res. Eval. Cent. 2015, 4, 73–89. [Google Scholar]

- Khondker, H.H. Glocalization as Globalization: Evolution of a Sociological Concept. Bangladesh E-J. Sociol. 2004, 1, 12–20. [Google Scholar]

- Levitt, T. The globalization of markets. Harv. Bus. Rev. 1983. Available online: https://hbr.org/1983/05/the-globalization-of-markets (accessed on 2 September 2021).

- Yip, G.S. Global Strategy…In a World of Nations. Sloan Manag. Rev. 1989, 31, 29–41. [Google Scholar]

- Malnight, T.W. The Transition from Decentralized to Network-Based MNC Structures: An Evolutionary Perspective. J. Int. Bus. Studies. 1996, 27, 43–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svensson, G. “Glocalization” of business activities: A “glocal strategy” approach. Manag. Decis. 2001, 39, 6–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segal-Horn, S. The Limits of Global Strategy. Strategy Leadersh. 1996, 24, 12–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grigorescu, A.; Zaif, A. The concept of glocalization and its incorporation in global brands’ marketing strategies. Int. J. Bus. Manag. 2017, 6, 70–74. [Google Scholar]

- Dumitrescu, L.; Vinerean, S. The glocal strategy of global brands. Stud. Bus. Econ. 2010, 5, 147–155. [Google Scholar]

- Dess, G.D.; McNamara, G.; Eisner, A.B. Strategic Management, 8th ed.; McGraw Hill Education: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Prakash, A.; Singh, V.B. Glocalization in food business: Strategies of adaptation to local needs and demands. Asian J. Technol. Manag. Res. 2011, 1, 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Robertson, R. Globalisation or glocalization? J. Int. Commun. 1994, 1, 33–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, Y.Y. The coming challenge: An entrepreneurial pathway for the 21st century. In Singapore: Re-Engineering Success; Mahizhnan, A., Yuan, L.T., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Singapore, 2000; pp. 152–162. [Google Scholar]

- Ritzer, G. Rethinking globalization: Glocalization/grobalization and something/nothing. Sociol. Theory 2003, 21, 193–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritzer, G. The Globalization of Nothing. SAIS Rev. (1989–2003) 2003, 23, 189–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, K. Corporate Nationalism and Glocalization of Nike Advertising in “Asia”: Production and Representation Practices of Cultural Intermediaries. Sociol. Sport J. 2012, 29, 42–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawford, A.; Humphries, S.A.; Geddy, M.M. McDonald’s: A Case Study in Glocalization. J. Glob. Bus. Issues 2015, 9, 11–18. [Google Scholar]

- Crowe, S.; Cresswell, K.; Robertson, A.; Huby, G.; Avery, A.; Sheikh, A. The Case Study Approach. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2011, 11, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rhee, D.K.; Choi, J. The Globalization Strategy of Nongshim: Foreign Direct Investment in China. Int. Bus. Rev. 2006, 10, 137–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, J.Y. Taste of Fire + Scent of Jja-Jang + Texture + Naming + Convenience Store … ‘The King of Jja-Jang’ That Scaled up the Instant Noodle Market Game. Available online: https://dbr.donga.com/article/view/1101/article_no/7368 (accessed on 12 June 2021).

- Kim, S.K. Nongshim’s CEO Joon Park Says “Create Low-Growth Breakthrough with 7 Survival Missions”. Available online: http://biz.newdaily.co.kr/site/data/html/2016/01/29/2016012910009.html (accessed on 12 June 2021).

- Koo, N. Food Culture in the World. Seoul, 1st ed.; Gyomoon Publisher: Paju, Korea, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- International Food Information Council. 2020 Food & Health Survey. 10 June 2020. Available online: https://foodinsight.org/2020-food-and-health-survey/ (accessed on 17 June 2021).

- World Instant Noodles Association. Available online: https://instantnoodles.org/en/noodles/market.html (accessed on 11 May 2020).

- Npd. Available online: https://www.npd.com/wps/portal/npd/us/news/thought-leadership/2021/10-consumer-trends-we-re-watching-in-2021/ (accessed on 12 June 2021).

- Dairy Foods. Available online: https://www.dairyfoods.com/articles/94399-covid-19-pandemic-has-transformed-the-way-americans-shop-eat-and-think-about-food (accessed on 10 June 2020).

- Ahn, C.Y. [A Microscopic Analysis of Ramyun Market’s Expansion into America 1] Unveiling Nissin-Maruchan-Nongshim Business Report. Available online: https://sundayjournalusa.com/2019/01/17/%EB%AF%B8%EA%B5%AD%EC%A7%84%EC%B6%9C-%EB%9D%BC%EB%A9%B4%EC%8B%9C%EC%9E%A5-%ED%98%84%EB%AF%B8%EA%B2%BD%EB%B6%84%EC%84%9D1-%EB%8B%88%EC%8B%A0-%EB%A7%88%EB%A3%A8%EC%B0%AC-%EB%86%8D%EC%8B%AC-%EC%82%AC/ (accessed on 13 June 2021).

- Kwak, Y.M. [Investment Analysis] Forecasting Nongshim’s High Growth in Foreign Markets. Available online: http://www.e-focus.co.kr/news/articleView.html?idxno=4759 (accessed on 12 June 2021).

- Choi, B.N. [Korea Spirit UP23] Nongshim Captures Global Taste Buds with Ramyun. Available online: http://www.greenpostkorea.co.kr/news/articleView.html?idxno=120304 (accessed on 12 June 2021).

- Lee, S.B. ‘A Semiconductor of the Food Industry’ Shin-Ramyun Awes Global Market… K-Food Beyond K-Pop. Available online: http://news.kmib.co.kr/article/view.asp?arcid=0012801770&code=61121111&cp=nv (accessed on 12 June 2021).

- Lee, J.W. [The Kick of the Distribution Companies ⑦ Nongshim] The Death of ‘The Ramyun King’… His Predecessor, Shin Dong-Won, Should Bear the Crown. Available online: http://www.thepowernews.co.kr/view.php?ud=20210310113853919601286bacad_7 (accessed on 12 June 2021).

- ECONOMY Chosun. Available online: http://economychosun.com/client/news/view.php?boardName=C01&t_num=13605845 (accessed on 12 June 2021).

- Kang, Y.Y. Kouki Ando, CEO of Nissin Foods Who Turned It into a Global Instant Noodle Company, Wins Over American Consumers and Overthrew His Father’s Hit “Cup Noodles”. Available online: https://www.hankyung.com/news/article/2014052973191 (accessed on 12 June 2021).

- Kim, J.Y. Push and Pull with Jin-Ramyun and Ketchup…Ottogi’s Foreign Sales Expected to Hit a Record High. Available online: https://www.news1.kr/articles/?4137596 (accessed on 12 June 2021).

- Yoo, H.H. The Business Battle between Korean and Japanese in the US Market…Can Nongshim’s ‘Shin-Ramyun’ Catch up with Japan’s No.1 Ramyun ‘Maruchan’? Available online: https://www.etoday.co.kr/news/view/1782638 (accessed on 12 June 2021).

- Yoon, A. The Ratio Nongshim’s R&D Investment to Sales Is the Biggest in the Industry. Available online: http://www.ceoscoredaily.com/news/article.html?no=68492 (accessed on 12 June 2021).

- CEO SCORE. Available online: http://www.ceoscore.co.kr/ (accessed on 12 June 2021).

- Hwang, S.A. Vice-Chairman and Nongshim Jr. Shin Dong-Won Scores Big with ‘Jja-Wang’, Just Like His Father, ‘The Master Craftsman of Ramyun’. Available online: https://biz.insight.co.kr/news/187817 (accessed on 18 June 2021).

- Lee, J.G. The Trend of the World Ramyun Industry and Korea’s Ramyun Industry. Korea Rural. Econ. Inst. 2016, 194, 51–72. [Google Scholar]

- Son, S.J. The Best in Human Resources and Technology, Nongshim’s R&D Center. Food Ind. Nutr. 2016, 21, 44–46. [Google Scholar]

- Jeon, J.H. Nongshim’s Ramyun Enters all 4692 Store Locations of Walmart…It Sells 2038 of Them Every Minute all over the World. Available online: https://biz.chosun.com/site/data/html_dir/2017/11/07/2017110701600.html (accessed on 12 June 2021).

- Nongshim Annual Report 2018. Available online: http://eng.nongshim.com/ir/annualReport (accessed on 12 June 2021).

- THE RAMEN EATER. Available online: https://www.theramenrater.com/2012/06/05/meet-ther-manufacturer-an-interview-with-nongshim-america/ (accessed on 3 October 2020).

- Yeon, H.W. The Keyword of Nongshim’s Success in the U.S. Is ‘Distribution’. Available online: https://www.thebell.co.kr/free/content/ArticleView.asp?key=201510060100010240000631&lcode=00 (accessed on 12 June 2021).

- Lee, S. “Quality Verification Is a One-Time Opportunity to Make It to the Shelves” How Did Shin-Ramyun Make It to the Walmart Shelves all over the U.S.? Available online: https://www.asiae.co.kr/article/2020071109361531302 (accessed on 12 June 2021).

- Kim, B.R. Shin-Ramyun Enters the Buildings of the U.S. Department of Defense and Congress … The ‘Spicy Flavor’ Enraptures Global Consumers. Available online: https://www.hankyung.com/economy/article/202004150812i (accessed on 12 June 2021).

- Min, H.J. Shin-Ramyun Lures in the Local Consumers of the US Market, How Are Its Sales Flying so High? Available online: http://www.biznews.or.kr/news/article.html?no=8486 (accessed on 12 June 2021).

- Why the Hot & Spicy Food Trend Is an Exciting Opportunity; FoodNavigator-USA: New York, NY, USA, 2019; Available online: https://www.foodnavigator-usa.com/News/Promotional-Features/Food-Industry-Research-Hot-Spicy-Food-Trends-Applications-and-More (accessed on 12 June 2021).

- Longnecker, L.M.; Lee, J. The Korean Wave in America: Assessing the Status of K-pop and K-drama between Global and Local. Situat. Cult. Stud. Asian Context 2018, 11, 105–127. [Google Scholar]

- Hong, S.B. “Thank You ‘Parasite”… Nongshim’s Stock Price Rides High on Jjapaguri’s Popularity. Available online: https://cnews.fntimes.com/html/view.php?ud=2020021314385319866c0eb6f11e_18 (accessed on 12 June 2021).

- Im, H.H. Samyang Foods Enters the North American Market by Targeting Hispanics Consumers. Available online: https://ccnews.lawissue.co.kr/view.php?ud=201807032211421595d7f4c63cc6_12 (accessed on 13 June 2021).

- Kim, M.J. “Buldak Bokkeum Myun Is Our Lucky Charm”… Samyang Foods Enrapture Global Taste Buds with the ‘Spicy Flavor’. Available online: http://www.newsway.co.kr/news/view?tp=1&ud=2020061714410221012 (accessed on 12 June 2021).

- Yoon, H.H. [Rivalry in the Distribution Industry] ‘The K-Ramyun Trio’ Nongshim·Ottogi·Samyang Foods… Makes a Breakthrough in the COVID-10 Situation. Available online: https://biz.chosun.com/site/data/html_dir/2020/08/24/2020082400169.html?utm_source=urlcopy&utm_medium=share&utm_campaign=biz (accessed on 12 June 2021).

- Shin, M.J. Prices Skyrocket at Year’s End.. Prices of Jin-Ramyun and Choco-Pie Price Yet Remains Frozen for Years. Available online: https://news.v.daum.net/v/20181115091800790 (accessed on 12 June 2021).

- Statista. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/257127/per-capita-consumption-of-fresh-fruit-in-the-us/ (accessed on 22 June 2021).

- Deloitte Insights. Available online: https://www2.deloitte.com/us/en/insights/industry/retail-distribution/future-of-fresh-food-sales/fresh-produce-consumer-trends.html (accessed on 22 June 2021).

- KB Securities. Available online: https://rdata.kbsec.com/pdf_data/20190123154510040E.pdf (accessed on 22 June 2021).

| Reference | Approach to Glocalization |

|---|---|

| Harvard Business Review (late 1980s) | A Japanese term for glocalization, “dochakuka”, meaning adapting farming techniques to one’s local condition [12] |

| Robertson (1994) | The idea of glocalization in its business sense is closely related to “micro-marketing” |

| Wong (1998) | A global company does not mean it has gone all the way; there are companies that are part-global, part-regional or part-local, involving different domains |

| Svensson (2001) | The focus on balance and harmony is crucial in a company’s global strategy approach and its glocalization of business activities |

| Ritzer (2003) | Glocalization is the interpretation of the global and the local, resulting in unique outcomes in different geographic areas |

| Kobayashi (2012) | Corporate glocalization requires substantial negotiation and collaboration with local cultural intermediaries |

| Year | Nongshim’s Accomplishments |

|---|---|

| 1960s | Nongshim enters the ramen industry as a late mover |

| 1970s | Nongshim’s investment in R&D development continues |

| 1980s | A new facility is built in Ansung for making the soup base Nongshim wins over 50% of the market share in the industry |

| 1990s | Nongshim builds facilities in China’s Shanghai and Qingdao Active overseas exportation of ramen products is initiated by Nongshim |

| 2000s | New LA Plant started its operation in 2005 (12155 6th Street, Rancho Cucamonga, CA, USA) Nongshim leads a specialized factory project for health-friendly noodles |

| 2010s | Nongshim enters into a direct transaction contract with Walmart Nongshim’s 50-year anniversary is celebrated in 2015 and Nongshim produces several hit products |

| 2017 | R&D cost-to-sales ratio | 1.13% |

| sales | 2,208,260 | |

| R&D cost | 24,909 | |

| 2018 | R&D cost-to-sales ratio | 1.25% |

| sales | 2,236,436 | |

| R&D cost | 27,998 | |

| 2019 | R&D cost-to-sales ratio | 1.20% |

| sales | 2,343,942 | |

| R&D cost | 28,186 |

| A. Production Differentiation Strategy (Positioning Premium) | B. Promotion Strategy |

|

|

| C. Accessing Mainstream Distribution Channels and Step-by-Step Strategy | D. Brand Power Improvement |

|

|

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lee, S.; Kim, H.; Choi, S. Corporate Glocalization Strategy of Nongshim in America: The “Pendulum Theory” of Globalized Localization. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2021, 7, 205. https://doi.org/10.3390/joitmc7040205

Lee S, Kim H, Choi S. Corporate Glocalization Strategy of Nongshim in America: The “Pendulum Theory” of Globalized Localization. Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity. 2021; 7(4):205. https://doi.org/10.3390/joitmc7040205

Chicago/Turabian StyleLee, Songmi, Hyunjung Kim, and Seungho Choi. 2021. "Corporate Glocalization Strategy of Nongshim in America: The “Pendulum Theory” of Globalized Localization" Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity 7, no. 4: 205. https://doi.org/10.3390/joitmc7040205

APA StyleLee, S., Kim, H., & Choi, S. (2021). Corporate Glocalization Strategy of Nongshim in America: The “Pendulum Theory” of Globalized Localization. Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity, 7(4), 205. https://doi.org/10.3390/joitmc7040205