Abstract

Surviving in a humanitarian disaster such as the COVID-19 pandemic is a big challenge for micro, small, and medium-sized enterprises in all industries. Furthermore, cultural and creative firms face additional challenges. Many of those firms have survived the effects of the pandemic by proposing redesigned business models that have brought new added value in response to environmental hostility; they have strategically responded to the crises by adapting their business model. According to the extant literature, in VUCA (volatile, uncertain, complex and ambiguous) environments, dynamic capabilities are developed to detect and seize new opportunities and reconfigure the company’s assets. However, in very hostile environments, such as the COVID-19 crisis, the dynamic capabilities approach fails to explain the firm owners’ strategic decisions. A cross-case comparative analysis of ten micro and small firms in Spain’s cultural and creative industries has been conducted to examine how enterprises adapted to the COVID-19 crisis and the different organizational capabilities they implemented. This work proposes a new framework that postulates that business model adaptation is better understood under the emergency management theory and improvisational capability, instead of only under the dynamic capabilities lens. Organizational proximity in the diffusion of innovations under the open innovation paradigm is also critical to understanding the business model adaptation. From an academic perspective, this article enriches the current understanding of business model asdaptation by micro, small, and medium-sized enterprises in very hostile environments. The new framework intends to offer managers concrete guidelines about systematically adapting their business models in hostile situations.

1. Introduction

COVID-19 has generated a complex and exogenous shock in almost all industries and has affected most companies worldwide. The effects of the pandemic have caused significant distortions in labor markets and rendered many prevalent business models ineffective, at least temporarily. Although all companies have been affected, micro, small and medium-sized enterprises (MSME) have experienced the most important effects due to their limited capabilities to respond to the spring of unexpected competitive challenges. In 2020, 97% of Spanish companies were classified in this category. A total of 2,910,016 businesses (73%) are from the services industry, with the majority coming from the cultural industry [1]. Keeping cultural companies in good health and increasing their resilience to further environmental hostilities is essential for their survival but also for society in general. Heritage, visual and performing arts, cinema, music, publishing, and fashion design are strongly manifested in everyday life and contribute to our world’s social and economic development. As the European Union Commission pointed out in the Green Paper, “Unlocking the Potential of Cultural and Creative industries” [2] at the heart of our social fabric, culture shapes our identities, aspirations, and relationships with others and the world. Cultural and creative organizations are essential in our society.

To remain competitive in VUCA conditions, there is a consensus among researchers that organizations should develop capabilities to detect new opportunities, seize them, and reconfigure the assets available to adapt the company to exceptional circumstances. These capabilities are named dynamic capabilities.

Dynamic capabilities, by definition, are “change-oriented capabilities that help firms redeploy and reconfigure their resource base to meet evolving customer demands and competitor strategies” [3]. Dynamic capabilities englobe different routines such as sensing the market, seizing opportunities, leveraging and transforming or reconfiguring the business model [4,5,6,7]. However, a very hostile environment such as the COVID-19 pandemic makes this traditional approach obsolete in terms of strategic rethinking. When the immediate survival of the company is at stake, and harsh measures need to be promptly enforced, the dynamic capabilities approach alone fails to explain some of the strategic decisions made by firm owners.

This study intends to better understand how organizations from the Spanish cultural and creative industry have implemented business model adaptation during the COVID-19 pandemic. Following a perspective based on the resource-based view theory, this research uses an inductive approach to understand the underlying strategic foundations that lead to a successful adaptation of the business models of MSME in the Spanish cultural industry. A research framework is developed by borrowing theories from IT strategic impact and supporting operational activities to generate a new strategic impact, resource-based view, dynamic capabilities, improvisational capabilities, and open innovation.

The following research questions describe the intended contributions:

- What are the relevant factors that explain the cultural firms’ ability to adapt to a hostile environment while gaining competitive advantages?

- What is the role of improvisation in the success of adapting business models on cultural MSMEs in very hostile environments?

From an academic perspective, the new framework provides new conceptual elements that help clarify the strategic endeavors that underline the strategic challenges a firm can face in a crisis such as COVID-19. From a managerial perspective, the outlined framework should propose new insights for managers and decision-makers when strong competitive challenges affect the competitive strategy of MSMEs.

2. Background

As stated, our area of interest is business model adaptation in very hostile environments. This study follows the methodological parading based upon the grounded theory perspective [8]; therefore, theoretical preconceptions should be avoided [9]. The resultant theory will be merged with the literature in the ‘Discussion’ section. This literature review aims to explain the key terminology in our field and delimit the concepts we will address during the discussion.

2.1. Business Model Research from a Strategic Point of View

The business model (BM) concept represents a relatively new construct that has increasingly received attention over the last fifteen years [7,10,11]. Although there is no generally agreed-upon definition, there is a strong consensus that the BM encompasses customer-focused value creation, the delivery of a value proposition to specific market segments, the structure of the value chain required to deliver the value proposition, the mechanisms of value capture that the firm deploys, and how these elements are linked together in a value architecture [10,11,12,13]. This paper adheres to this definition.

The BM construct has been proved helpful by academics researching in the fields of e-commerce, strategy, innovation, and technology management [14].

2.1.1. Business Model Dynamics

Business Models are not static constructs; they can be a source of innovation and competitive advantages [7,14,15] and evolve and pivot over time.

In this vein, a research strand derived from the evolving changes in business models has flourished under the label of “business model dynamics” (BMD) [16]. BMD has been defined as “how companies change and develop their business models to achieve sustained value creation through time” [17]. Different patterns of BMD have been proposed to delineate “different levels of strategic changes in firms due to external effects” [15] including business model innovation, business model adaptation and business model evolution.

- Business model innovation (BMI) as a process, refers to “the search and development of new and sometimes disruptive modes of value proposition, value creation and value capture” [11] to disrupt market conditions [15,17,18], disrupt ecosystems [19], or enter a new international market [18].

- Business model adaptation (BMA) is the process of adapting a company’s business model to changes in the external environment to ensure its economic sustainability.

- Business model evolution is the process of incrementally reconfiguring the business model pieces that build the strategic challenges derived from the external effects. Minor adjustments in the BM are made for maintenance and fine-tuning.

“Each BMD instance represents a specific strategic value appropriation” [15].

2.1.2. Business Model Adaptation

As a specific instance of BMD, BMA identifies an update of the current BM to changes derived from the context [6,15,20]. BMA can be innovative or not, depending on the degree of novelty of the changes implemented [15,18,21]. As a consequence of the new context, several elements of the BM are promoted to answer those challenges, pivoting the BM towards new models. Companies adapt their BM when someone or something such as COVID-19 has disrupted the market.

BMA could fit any organization, but “incumbents are more motivated to adapt their current BM than to change it radically or create a new one” [15].

2.2. Business Model Adaptation and Open Innovation

Innovation in BMs not only comes from inside the companies. “Open business models” was a term coined by Chesbrough in 2006 to refer to “the desired end state of firm transformation” that has evolved from a “starting point” set up by a “closed” BM [22], “where firms collaborate with the ecosystem by building up value and innovating their business model to make use of the emerging opportunities” [23].

Saebi (2006) and Chesbrough (2006, 2014, 2017) agree on the benefits of implementing open innovation actions in firms [22,24,25,26]. Furthermore, Yun (2017) developed the concept of “developing circle of business models” [27] to improve the design of innovative BMs and successfully implement them under the open innovation paradigm.

Finnegan and Nilsson (2011) analyzed the effects of open innovation on the BM of govern agencies. In this case study of a set of Swedish cities, open innovation actions were promoted to identify four emergent classes of organizational transformations [28].

2.3. Resource-Based View and Organizational Capabilities

Organizational capabilities are crucial to success when changing a business model. The firm’s resource-based view (RBV) is a theoretical framework that assists in a deeper analysis of organizational capabilities. This perspective focuses on the internal organization of firms. It assumes that competitive advantages within these firms are achieved and sustained over time, thanks to their resources [29,30]. The RBV considers that firms are bundles of different resources heterogeneously distributed. Resource differences persist over time [31,32]. The organizational capabilities are part of a company’s resources to create competitive advantages [4].

Organizational capabilities are “the ability of a firm to perform a coordinated task, use organizational resources, and achieve a particular result” [30]. Organizational capabilities are well documented in the literature for large enterprises [4,7]. By comparison, there is little research to understand their applicability to small and micro-enterprises [30,33]. This paper also aims to contribute to reducing this gap.

The most widely accepted point of view is that there are two types of organizational capabilities: operational and dynamic [3,4,5,29,33,34].

2.3.1. Operational Capabilities

Operational capabilities are “a high-level routine (or collection of practices) that, together with its implementing input flows, confer upon an organization’s management a set of decision options for producing significant outputs of a particular type” [35]. Particularly, operational capabilities enable the firm to execute its main operating activities on a daily basis without significant changes, maintaining the current techniques, with no changes to the scale, supporting the same products and services for the same segments of customers [3]. Routines such as continuous improvement, strategy development and strategy implementation are considered operational capabilities [33].

2.3.2. Dynamic Capabilities

While operational capabilities are essential to sustaining and improving business performance, dynamic capabilities are “the firm’s ability to integrate, build, and reconfigure internal and external competencies to address changing environments” [4].

Teece (2007) claims that “dynamic capabilities enable firms to gain competitive advantage in rapid (technological) changing markets”. They also “enable firms to adapt to internal and external changes” [3]. In other words, organizations develop dynamic capabilities to deal with change.

2.4. Emergency Management

Emergency management is “the managerial function of dealing with risk and risk avoidance” [36]. It can be defined as “the study of how humans and their institutions interact and cope with hazards, vulnerabilities, and resulting events (i.e., emergencies, disasters, catastrophes, and complex humanitarian crises), particularly through activities related to preparedness, response, recovery, and mitigation” [37].

2.5. The Strategic Improvisation

Improvisation is defined as “the simultaneous conception and execution of an action” [38]. In other words, improvisation is the act of doing something spontaneously without planning as a rapid response to a problem. Although for decades, strategic planning has been considered the best way of ensuring competitive advantage by corporate leaders (Mintzberg, 1994), firms face substantial challenges in emergency environments that require different strategic responses.

Organizations that operate in a turbulent environment are more likely to improvise [39,40]. In their study, Villar and Miralles explore how organizations can employ improvisation to attain specific objectives during emergencies, such as the one caused by the Typhon Haiyan that impacted the Philippines in 2013. They demonstrate that improvisation “can be absorbed as a conscious mechanism that can aid the attainment of pre-established goals” [39].

2.6. Environmental Hostility and Business Model Adaptation

Recently, Rezaei et al. carried out extensive work to advance the research in business environmental hostility focusing their research on the adaptation of businesses and organizations after terrorist attacks. The outcome of this work demonstrates that two components can summarize the hatred of the business environment: competitive turbulence and regulatory turbulence [41].

Competitive turbulence is “a managerial perception of how much competition is in the market” and is related to the level of competition in the industry [41]. Competitive turbulence describes the increase of competition when a terrorist attack or a natural disaster reduces the customer base. In this situation, the ‘environmental hostility theory’ states that changes in organizations have to be expected due to market movements [41].

On the other hand, regulatory turbulence refers to “changes in government or regulation policies that can promote changes at the corporate level”. Four components have been identified for regulatory turbulence: legal factors, political factors, economic factors, and social factors [41].

3. Methodology

This paper is based on a multiple qualitative case study design [42]. The methodological paradigm followed is based on Glaser and Straus’s grounded theory perspective [8]. Glaser and Strauss articulated this methodology during their study—‘Awareness of Dying’ [8]. Its main aim is to develop a theory based on systematic data collection and analysis [9]. This model advocates that social scientists work “from the bottom up”: to derive theory from observations, not observations from theory [43].

The methodological goal has been to work with decision-makers of micro and small organizations from the cultural and creative industry to develop rich, detailed descriptions of their strategy and actions to adapt their BM to survive the COVID-19 crisis. Therefore, the phenomenon of interest is learning how firms survive the pandemic by adapting their business model to a very hostile environment. The unit of analysis is micro and small organizations from the Spanish cultural and creative industry. The observations were used as a starting point to develop a conceptual model [44,45].

3.1. Why a Multiple Case Study?

The ability of the case study as a research method is to answer “how” and “why” questions within real-world contexts. Yin (1994) described this method as: “an empirical inquiry that investigates a contemporary phenomenon within its real-life context, especially when the boundaries between phenomenon and context are not evident”. The case study method is used when researchers want to understand a phenomenon and its context in depth. The data is collected from a limited number of cases (ten in this research) to “focus on fewer subjects but more variables within each subject” [42]. A case study can follow one of two designs: a single case study or a multiple case study [46]. Each case should be viewed as a separate experiment in analyzing and interpreting multiple case studies.

3.2. Theoretical Sampling

The concept of theoretical sampling was first described by Glaser and Straus (1967) to generate theory from data. The process includes data collection and subsequent coding and analysis [8]. Ten managers from the cultural and creative industry companies were interviewed to obtain meaningful information about the topic. Ten cases gave the study sufficient theoretical saturation [47]. In subsequent conversations with other managers, it was clear that “incremental learning was minimal due to observing similar phenomena” [47]. Additional empirical investigations thereby ceased. Companies were chosen to have a broader view of the industry using convenience and purposive sampling, which are both non-probabilistic sampling techniques [48].

Researchers use them to select a sample from a population when randomization is impossible since it is too vast [48]. They are considered adequate when generalization is not an issue in the research aims. We decided to combine both techniques, and we obtained ten interviews that show a rich scope of cases representative of all of the essential cultural activities across this industry in Spain.

Companies were selected from the following primary subindustries: music and concert venues, event producers and festival organizers, artists/performers and companies, art galleries and art schools, museums and singular homes, to cover a wide range of the Cultural industry. They all agreed to participate in the research.

3.3. Data Collection

Various methods of data collection were employed:

- Semi-structured interviews with managers and decision-makers of MSMEs from Spanish cultural and creative industries were used to know more about the company’s whereabouts during the pandemic.

- Archival records from their websites were used to document their value proposition, public objective, and income models.

- Social networks were consulted to analyze how companies maintained their relationship with customers during the pandemic.

Interviews were carried out between April and September 2021. An online Zoom platform was used to hold the meetings. The interviews lasted from 50 min to 2 h and were video recorded with their permission. The content was transcribed with NVivo software and coded using this tool.

The managers interviewed were asked to describe their daily actions and strategy during the three stages of the pandemic: (1) full lockdown during March, April and May 2020; (2) intermittent lockdown from June 2020 to April 2021; and (3) “new normal” after April 2021. The interviews were semi-structured and open-ended. These interviews were complemented with written literature (e.g., pamphlets and websites) about their company or the cultural events created by themselves. The written materials were used to supplement details that were not mentioned or were unclear during the interviews.

The managers were asked to describe the practices and strategies that helped them overcome the crisis. Table 1 shows the ten cases analyzed. They all survived the COVID-19 crisis.

Table 1.

Case overview.

3.4. Content Analysis of the Interviews

We were able to download the recorded meetings from the Zoom platform as soon as each interview had finished. Key phrases were identified and moved into subcategories and categories during the open coding stage. Then, axial coding was applied, and relationships were identified between categories. A core category was identified and methodically related to the other categories in the final coding stage. Categories were integrated, and a grounded theory was identified. To ensure the validity and reliability of the outcomes, two researchers compared the results at the end of each stage of the analytical process to overcome the weakness of any possible biases. A cross-case triangulation was also performed to ensure the reliability of the results. The conclusions were contrasted with the extant literature.

3.5. Categories and Core Category

At the first stages of content analysis, three categories were identified:

- The core category: the strategic response to the COVID-19 pandemic.

- A secondary category: what changes were applied to the different components of their business model?

- A secondary category: the digitalization of some processes.

After the three initial interviews, it emerged that many of the actions undertaken by the managers were improvised. There was also evidence that innovation was taking place thanks to network proximity following the open innovation paradigm.

Questions about their degree of improvisation and innovation diffusion were included in the interviews that followed, and the first three managers were contacted and interviewed again. Two different secondary categories were added to the content analysis.

- Actions and strategies that can be considered improvisation.

- The origin of their innovation.

4. Findings

These are the most relevant findings regarding the strategic response and the adaptation of the BM of the companies and organizations in the cultural and creative industry:

- Three different strategic behaviors were observed among the organizations that survived: radical change, non-adaptation, and moderate adaptation.

- Companies and organizations adapted different components of their business model to survive.

- IT implementation had a vital role in the strategic adaptation of the companies.

- Organizational proximity had a prominent role in innovation diffusion.

We elaborate on these four findings in the following points.

4.1. Three Strategic Behaviours Were Observed among the Companies and Organizations That Survived

During the interviews, managers of the artistic and cultural companies and organizations revealed that they felt like victims of a terrorist attack, a war, or a typhoon. They were not prepared for anything. Even when the COVID-19 pandemic was raging in Italy, the Spanish government kept saying its health system was duly prepared and that no significant consequences were expected. A week before the restrictive measures were enforced, people were still carrying on as usual. No one had contingency plans when the total lockdown was imposed in Spain on 15 March 2020.

Table 2 shows the three strategic responses observed among the companies and organizations interviewed.

Table 2.

Strategic response to the crisis.

Companies that survived the crisis caused by the COVID-19 pandemic adopted three different strategic responses: (1) changed their business model radically (the monument and museum); (2) did not adapt their business model and “waited for the storm to pass” until the environment became stable (the theatre company, the photographer, and the opera house); and (3) adapted their business model, closing only the months of mandatory total lockdown (the festival organizer, the actress, the online ticket vendor, the online cultural aggregator, the archaeological museum, and the art school).

4.1.1. Companies Changed Their Business Model Radically

Some companies and organizations changed their business model radically to survive the crises. This is the case, for example, of the privately-owned monumental museum. Due to the lack of tourists, the owners decided to close the museum at the beginning of October 2020 and stop selling tickets to visit this listed building. At this moment, their income comes from renting the premises to a restaurant, a bank, a coworking, and a diverse group of businesses that have located their offices in the building. The museum, as such, has disappeared. They will most likely reopen it again in the near future.

4.1.2. Companies Did Not Adapt Their Business Model and “Waited for the Storm to Pass” until the Environment Had Become More Stable

We observed that some interviewed managers believed that adaptation was impossible. They decided to wait and see. This is the case of the opera house and many other organizations that are not part of this study, such as La Sagrada Familia, the under-construction basilic created by the modernist architect Gaudí; and La Pedrera, another singular building designed by Gaudí, that at present hosts a museum and different spaces for events. The same behavior could be observed with the photographer and the theatre company. They all had in common that they did not adapt their business model. They paused for months without any activity while waiting for environmental stability. They relied on their financial muscle (the opera house) or turned to other jobs (the photographer and the theatre company members).

4.1.3. Companies Adapted Their Business Model, Closing Only the Months of Mandatory Total Lockdown

If the managers’ perception was that adaptation was possible, they decided to adapt their business model. This is the case for many companies interviewed, such as the art school, the archaeological museum, the online aggregator, the ticket vendor, and even the actress. They changed several BM components to adapt their business model during the COVID-19 crisis or the “new normal”.

4.2. Companies and Organizations Adapted Different Components of Their Business Model to Survive

The companies that survived had in common that they adapted some BM components. Following the Business Model Canvas proposed by Osterwalder and Pigneur (2010), nine building blocks or components can be identified in the structure of a business model: the customer segments, the value proposition, the distribution channels, the customer relationship, the revenue streams, the key resources, the key activities, the key partnerships, and the cost structure [10]. We have chosen this model to analyze the changes made by cultural companies in their business models. Table 3 shows the changes on each component.

Table 3.

Changes in the business model.

4.3. IT Implementation Had a Vital Role in the Strategic Adaptation of the Companies

The role played by Information and Communication Technologies (from now on, ICT) has become an essential factor for economic growth in all types of industries. Researchers such as Viaene (2013) and Bassis (2018) agree on the importance of strategic value creation and value delivery through ICT and its role in business model innovation [49,50].

Technology is becoming an integral part of the products and services of diverse industries. There is a growing interest in understanding how organizations can succeed in their digital transformation. In companies, tensions spring from the opposition between investing in digital tools that generate value in the long-term and obtaining value in the short term. MSMEs, however, also suffer from another problem: the fact that digital tools are constantly changing and must be adapted as innovation and competitive pressure progresses. Failure to see short-term performance causes them to be reluctant to implement technological changes [51].

At the beginning of the COVID-19 crisis, customers were not allowed to physically go to the premises of the cultural companies, therefore managers needed digital products and services and despite initial reluctance, these did appear. Nevertheless, the implementation of ICT solutions takes time, and during the first phase of BMA, they had to improvise immediate solutions with the current stock of ICT assets that managers had on their hands. In the second phase, the implementation was carried out. Virtual tours were created, e-commerces were in place, and online courses were offered.

4.4. Organizational Proximity Had a Prominent Role in Innovation Diffusion

For MSMEs it is essential to identify cooperative opportunities or competitive challengers from their knowledge flow network. All companies agreed that being part of an association or a network of peers had helped them keep up-to-date with innovations and help them find viable solutions to the required adaptation of their business.

The actress also highlighted that belonging to a theatre association provided her with moral support during the pandemic. The marketing manager of the archaeological museum made the same statement about the advantages of being part of a network of museums and cultural venues “we have been working weekly with the Catalan network of museums, sharing innovations and possible solutions to our common problems”, he stated.

5. Discussion

At the beginning of the pandemic, customers’ needs were altered. People stayed at home and could not attend any type of live cultural event. Companies and organizations began to analyze the new customer needs and change their value proposition accordingly: planned virtual tours and online services. Nevertheless, as the COVID-19 pandemic was an emergency, the reaction could not wait to create all-new planned services and products.

Researchers such as McGrath (2009) agree that in emergencies, companies and organizations must simultaneously “reduce risk and seize opportunities” [52]. Therefore, disasters such as the COVID-19 pandemic can also be an “agent of social change in recovery and reconstruction” [53] if companies are capable of seizing the opportunities and gaining competitive advantages by adapting their business models. We have observed this phenomenon in the companies interviewed.

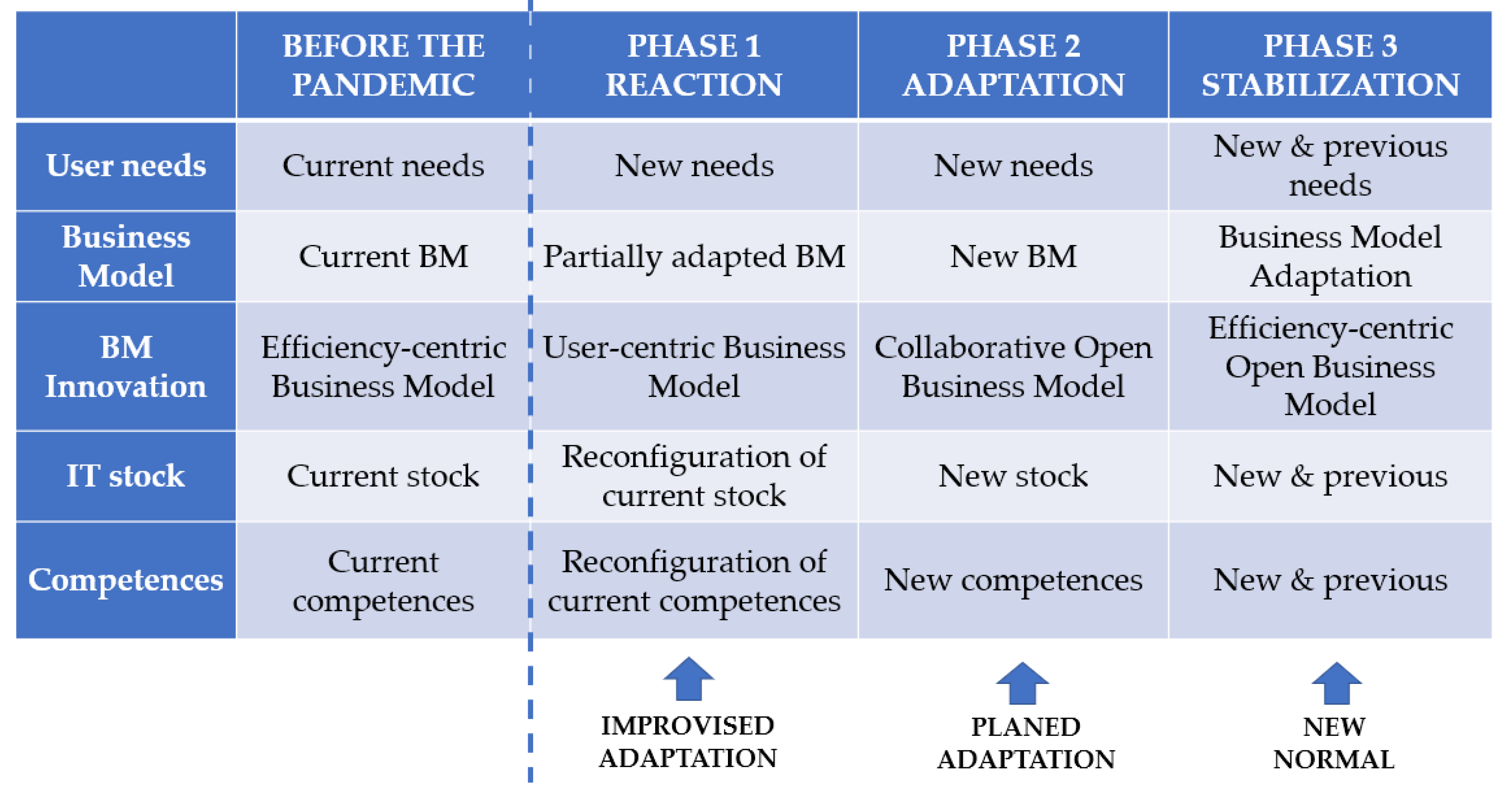

5.1. The Three Phases of Business Model Adaptation to a Crisis Environment

Analyzing the interviews, it was clear that the adaptation had been made in three phases:

- In the first months, companies and organizations improvised to reconfigure their assets and capabilities to respond to market needs rapidly while planning new strategies and actions for the future.

- After a few months, the planned actions were in place, and the companies implemented what they considered necessary for their value architecture.

- At the time of writing, companies are adapting old assets and capabilities, plus the new ones acquired, to the “new normal”. This new competitive environment is labelled as “new normal” to emphasize that it differs from before the COVID-19 pandemic.

5.1.1. Phase 1—The Reaction

The conception of the actions to adapt the cultural business to its daily reality and its executions were simultaneous. No planning or strategy was used to deal with the uncertainty of every day. Most of the companies interviewed openly agreed that their strategy in this first month was “not having a strategy” working day by day, confronting their challenges.

For example, the archaeological museum did not offer formal virtual tours but after analyzing the current assets and the current IT stock, they created short videos with images from Google Street View and matched them with the content of the audio guides. They improvised virtual guided tours and offered them to online visitors while the museum was closed and planned a proper virtual tour.

Another example of improvisation can be observed by analyzing the behavior of the managers from the art school. Due to COVID-19, students were not allowed to attend the art school, and the school could not carry out any of the activities they had been offering to other schools. To maintain a source of income until their online courses were ready, they created an e-commerce website to sell merchandising of drawings made by their students using a drop shipping business model (print on demand). This action was not planned; it was improvised to create an alternative source of income during the development of the planned behavior.

Finally, we have example of Marta, the actress and the director of a theatre company. The company had not been able to perform for almost a year. In November 2020, Marta created her website to market the online training courses she had just made up.

The behavior of these organizations is consistent with the theory of planned behavior (PBT), which states that “the intentions to perform a particular behavior can be predicted from the subject attitude toward the behavior, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control” [54]. By definition, planning is impossible when norms constantly change, and improvisation is the only way to face everyday challenges.

Business models had to be changed and adapted, improvising to fit the urgent needs of the customers. The innovation was created by reconfiguring the current assets, the companies’ existing capabilities, and the IT stock they had at that moment. “The higher the turbulence of the business environment, the more critical the enterprise’s” improvisational capabilities become [55].

Organizations that operate in a turbulent environment are more likely to improvise [39,40]. In their study, Villar and Miralles explore how organizations can employ improvisation to attain specific objectives during emergencies, such as the one caused by the Typhon Haiyan that impacted the Philippines in 2013. They demonstrate that improvisation “can be absorbed as a conscious mechanism that can aid the attainment of pre-established goals” [39].

5.1.2. Phase 2—Planned Adaptation

In Phase 2, customers’ needs were still different to pre-pandemic times, but months had passed, and companies and organizations had had enough time to plan and act accordingly to their new strategies. Business models changed how their value was communicated, the delivery of their services, income models and the public objective while adapting their value proposition to the situation. Innovation was created by sharing information between peers, associations and observing the entire cultural ecosystem. Without being consciences of it, a new parading of business model open innovation was in place: a collaborative open business model. Learning from the experiences of others, new technology was acquired, and new competencies were learned.

5.1.3. Phase 3—Stabilization

In Phase 3, the new business models were in place, and companies and organizations were adapted to the “new normality”. Those who adapted and survived learned new capabilities, implemented new technology, and found new competitive advantages, becoming more resilient to new environmental hostility.

Those who did not adapt and survived since they had enough financial muscle, consumed part of it and diminished its resilience but are still on the market.

Figure 1 shows a proposed framework to understand the different phases of adapting the business model in the cultural and creative industry.

Figure 1.

The three phases of business model adaptation in the cultural and creative industry.

5.2. COVID-19 from the Lenses of the Emergency Management Theory

From the lenses of the emergency management theory and considering the improvisation capability, the adaption of the business models of cultural and creative MSMEs in the first phase is easier to understand. The findings suggest that in a hostile environment such as the COVID-19, in the first phase of their adaptation, cultural and creative firms applied different improvisational actions to adapt some business model components to survive the effects of the crisis.

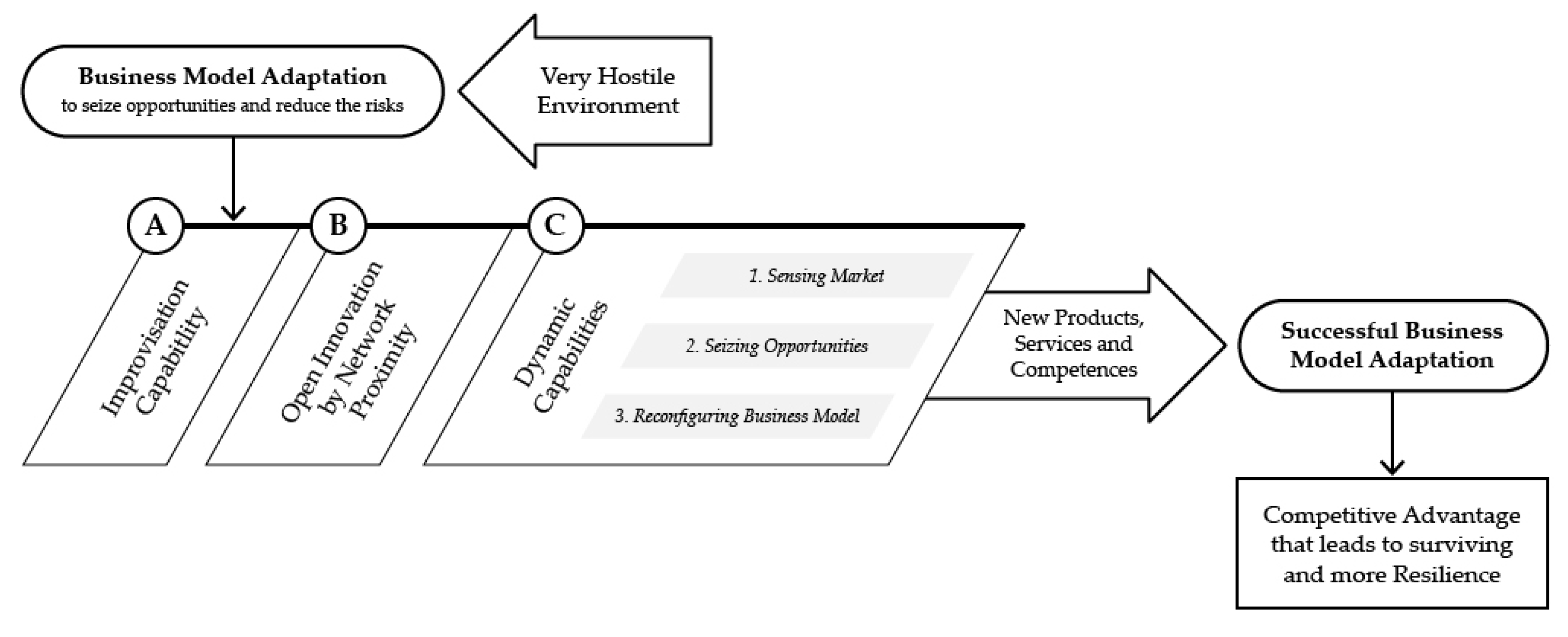

This research aims to understand the relevant factors that explain the cultural firms’ ability to be adaptative. To do so, a conceptual framework to explain the results and the survival path to a successful business model adaptation (see Figure 2) is proposed.

Figure 2.

This research framework is the survival path to successful BMA of the firms in terms of the BM emergency management perspective.

The relevant factors that explain the cultural firms’ ability to adapt and gain competitive advantages and more resilience in times of very hostile environment: (A) The immediate deployment of some characteristics that can be found in organizational improvisation behavior; (B) the capacity to absorb innovation from its network and ecosystem; (C) and the acquisition and deployment of dynamic capabilities such as absorption capacity and uncertainty management.

5.2.1. COVID-19 Crisis and Environmental Hostility

During the first COVID-19 lockdown, the traditional cultural industry market disappeared from March to May in Spain due to mobility restrictions. After the total lockdown, premises were allowed to reopen but with restrictions. The environmental hostility theory states that, when faced with a lack of customers, organizational behavior changes as business activities become more influenced by market movements [41].

Companies and organizations from the cultural industry have suffered regulatory turbulence for more than two years. Restrictions on the seating capacities or entrance restrictions in theatres, museums, or public events have fluctuated throughout the pandemic. Managers have had to face constantly changing post-confinement regulations and constraints, sometimes as often as every week, as waves of infection circled the globe. Regulatory forces have had a massive impact on the Cultural industry companies and organizations and have been a great source of pressure and stress for the managers.

On top of that, a domino effect caused by layoffs and provisional downsizing plans of many companies triggered a change in the social status of many families as their quality of life and their lifestyle plunged, affecting all industries, but especially the consumption of cultural goods and services, shrinking the market and causing competitive turbulence as well.

In short, the COVID-19 crisis has created a very hostile environment, and companies have been forced to adapt their business models to survive, especially in the cultural and creative industry.

5.2.2. The Development of Some Characteristics That Can Be Found in Organizational Improvisation Behavior

Dynamic capabilities cannot fully explain the adaptation of cultural and creative companies and organizations; improvisation capabilities must be considered. There is a link between strategic improvisation and company performance in times of emergency and crisis. When the immediate survival of a company is in question, long-term strategies lose effectiveness and management resort to improvisational processes [55,56,57,58].

Research on organization theory such as Weick (1998) and Barrett (1998) suggested the jazz band metaphor to explain the functioning of an organization. Drucker (1998) suggested that “the twenty-first-century leader will be like an orchestra conductor” [59].

Improvisational working practices need a supportive organizational culture in order to flourish. This type of organizational culture is linked to the company’s decision-makers self-confidence and ability to improvise effectively given a range of possible actions and results.

Improvisation to adapt the company’s business model to seize possible opportunities has many similitudes to the “opportunity-driven entrepreneurship” concept. This complex term is defined as “the entrepreneurial decisions motivated by the perception and exploitation of innovative business ideas that can lead to gains and business growth” [60]. When a new opportunity to obtain sources of income appears, entrepreneurs go for it without great strategic plans or even without a long-term plan.

Some authors do not consider improvisation a dynamic capability or an operational capability, arguing that it is not a routine—“learned, highly patterned, repetitious or quasi-repetitious, founded in part in tacit knowledge” [35]. Other authors consider that improvisation can drive strategic advantages in turbulent environments and therefore should be regarded as a third type of capability. They describe it as “the learned ability to reconfigure operational capabilities spontaneously” [55]. “The higher the turbulence of the business environment, the more critical the enterprise’s dynamic and improvisational capabilities become” [55].

In other words, and answering our research question “what is the role of improvisation in the success of the adaptation of business models on cultural MSMEs in very hostile environments” we conclude that improvisation has been their primary capability, although dealing with complex problems, learning new abilities, and having organizational flexibility are also some of the capabilities that saved them from bankruptcy.

5.2.3. Open Innovation by Network Proximity

At the same time, open innovation by network proximity must be considered to fully understand the adaptation of enterprises from the cultural and creative industry. Without the help and collaboration of peers, innovation would not have been possible.

Proximity influences the diffusions of innovation and is one of the driving forces for creating an open innovation ecosystem and leading its evolution [61]. Zhang and Wang (2021) identified four dimensions of proximity: technological proximity, spatial proximity, organizational proximity, and temporal proximity [61]. Their results show that “organizational proximity positively affects the diffusion of innovations”. Ferras-Hernandez et al. (2018) studied the relationship between enterprise innovations and proximity, focusing their research on innovation activities. They identified the primary factors driving the industrial cluster’s innovation transformation; organizational proximity was among them [62].

5.2.4. The Acquisition and Deployment of New Capabilities

Despite the distance, all of the companies and organizations studied had to learn to work together. The archaeology museum indicated that this had been one of the significant challenges since they have had to learn to communicate jointly from the different departments from their own homes. It should also be noted that although distance group communication tools already existed, no one had previously used them so intensively. Zoom, Google Meet, MS Teams, and all of these tools were un-used by much of the cultural industry. Everyone had to learn how to use them and how they could be incorporated into the work dynamics of each company.

For the museum, reviewing all of the digital content to see if it could be used to create virtual tours or communicate has also been helpful to realize certain shortcomings. For example, when reviewing the audio guides, they realized that while the guides were inclusive in the sense that they are helpful to people in the languages in which the guides are narrated, the guides have no use for blind people as they did not describe the pieces. Thanks to the revision, there is now a project to redo the audio guides and make them inclusive for the blind.

The adaptation itself has been a learning experience. All innovation activities require new competencies. Until the COVID-19 pandemic, organizations had not worked methodically to create online content, virtualize user experiences, or work remotely as a team. All interviewees highlighted the learning effort they had to make. The knowledge absorption capability has been crucial in all organizations.

Instead of being fully cancelled, many concerts, theatre acts, expositions, and events were rescheduled for later dates after a few months. All interviewees have indicated that they had to learn to work with the uncertainty of whether things could be carried out. Uncertainty management is a skill that everyone had to learn.

Business models will most probably continue to adapt as the post-COVID-19 scenario develops. Despite the vaccine and achieving herd immunity in certain cities, managers are still uncertain about what the future holds. When asked when they expect to resume normal operations, they perceive that at least another year will be needed to reach normality.

5.3. Theoretical Implications: BMA in Very Hostile Environments Is Better Understood under the Lenses of Emergency Management Theory and Improvisation Capabilities

A revision of the existing literature has shown that much attention has been paid to studies on innovation in business models in companies and public organizations [63,64]. Researchers have paid limited attention to better understanding how cultural and artistic organizations can manage and evolve their BM [63].

Ernst et al. demonstrate in a case study of BMI in the publicly-funded cultural and creative industry (specifically, the Van Abbe Museum in Eindhoven-Netherlands) that cultural venues can act as laboratories of BMI [65]. Schiuma and Lerro introduce and analyze the “Business model prism for the arts and cultural organizations” as a multidimensional framework to map the “as is” structure and the logic of their business model [63].

This article proposes a new perspective and a framework to understand the business model adaptation in very hostile environments. It suggests that in environments such as the crises created by the COVID-19 pandemic, business model adaptation can be better delimited using the emergency management theory and improvisational capability than solely under the dynamic capabilities lenses.

The improvisation capability of an MSME is a crucial factor to its survival. At the same time, network proximity has a prominent role in disseminating innovations and unveils itself as a critical factor in the thriving BMA of cultural and creative companies and organizations.

5.4. Managerial Implications: Successful Business Model Adaptation

Museums, theatres, concert halls, and festivals have been forced to close for months, leaving artists and performers without work for nearly a year. Some organizations have not been able to adapt, while others have improvised in response to whatever they came up against and adapted different components of their business model. The issues raised in this article offer some light on how managers can gain concrete guidelines about systematically and purposefully approaching BMA in hostile environments.

The first step is to identify the key drivers of change and understand these drivers’ impact on the business model. The second step is to identify the key capabilities needed to respond to the drivers of change. The third step is to identify the gaps between the current capabilities and the needed capabilities to adapt the business model successfully. The fourth step is to develop a plan to close the identified gaps while at the same time, confronting the emergency with the current stock of assets and capabilities, improvising to maintain the company afloat while the adaptation plan is deployed. The fifth step is to monitor the results of the action and adapt the company or organization to the new and less hostile environment—all sharing knowledge with peers from the same industry.

6. Conclusions, Limitations, and Future Research Perspectives

This study aims to understand organizational capabilities in the cultural and creative industry to respond to the COVID-19 crisis. Literature on business model dynamics affirms that, in VUCA environments, dynamic capabilities are developed to sense new opportunities and seize them, while reconfiguring the current assets to adapt the company to the unique situation. However, in very hostile environments such as the COVID-19 crisis, business model adaptation is better understood under the emergency management theory rather than just under the dynamic capabilities lenses.

6.1. Conclusions

6.1.1. BMA Has Been Implemented in Three Phases

The evidence of this study suggest that the BMA has been implemented in three phases:

Phase 1—The Reaction: the conception of the actions to adapt the cultural business to its daily reality and its executions are simultaneous. Companies improvise their immediate adaptation while planning for the near future and analyzing the gap between their assets and the assets they need.

Phase 2—Planned Adaptation: the future actions planned during phase 1 are now in place. Companies have a new BM and a new stock of competencies. Innovations are shared with other organizations.

Phase 3—The Stabilization: companies adapt to “the new normality” and return to their efficiency-centric BM with new and old components and capabilities.

6.1.2. Survival Strategies

In this research, we have observed that companies and organizations from the cultural and creative industries had three different survival strategies. As the emergency management theory predicts, the first two options are to adapt their business model radically or incrementally to minimize the risks and seize the opportunities arising from the crisis. The third strategy has been to put everything on stand-by and wait for “the storm to pass”, although they can rely on their financial muscle and the funding from COVID-19 aids.

6.1.3. Improvisation as a Key Factor to Understanding the Survival of MSMC

The COVID-19 crisis has created a very hostile environment, and companies have been forced to adapt their business models to survive, especially in the cultural and creative industries. In this article, the authors postulate that to fully understand BMA in times of environmental turbulence and hostility such as the COVID-19 pandemic, the improvisation capability of an MSME is a crucial factor for its survival. To make fast decisions without in-advance planning leads to survival if the decisions are correct.

6.1.4. The Leading Role of Open Innovation by Network Proximity

Open innovation by network proximity plays a primary role in fully understanding the cultural and creative industry’s adaptation, and it is critical for the diffusion of the innovations. This fact’s management and policy implications are clear; politicians and decision-makers need to support proximity between innovation entities.

6.2. Limitations

This paper is a new step of a comprehensive research project in business model adaptation. We realize that the improvisation capability and the innovation by network proximity were present in the companies’ actions that led to their business model adaptation during the COVID-19 crisis, but we do not know more about the firms that did not adapt. On the other hand, as with all qualitative research, the outcome lacks any potential generalization effort. It is unclear to what extent the results can be made valid for other companies and organizations. A quantitative approach to the same subject would be advisable. At the same time, we analyzed the behavior of the companies and organizations of the cultural and creative industry in Spain; we think that a broader take on other industries and other countries would enrich our proposal to analyze BMA from the emergency management theory and improvisational capabilities.

6.3. Future Research Perspectives

More research is needed to better understand the relationship between how a leader approaches the act of improvising and the company’s resilience. It is necessary to deepen the analysis on how the leader’s resilience intervenes in improvisation. Furthermore, exploring leadership improvisation based on the resilience of the leaders can shed some light on a deeper understanding of the first phase of business model adaptation during the COVID-19 crisis. We also believe that an analysis of the correlation between the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic and the change to more sustainable business models suggested by Popescu (2020) [66] would be attractive from the research point of view.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.P.-F. and F.M.; methodology, M.P.-F. and F.M.; software, M.P.-F. and F.M.; validation, M.P.-F. and F.M.; formal analysis, M.P.-F. and F.M.; investigation, M.P.-F. and F.M.; resources, M.P.-F. and F.M.; data curation, M.P.-F. and F.M.; writing—original draft preparation, M.P.-F. and F.M.; writing—review and editing, M.P.-F. and F.M.; visualization, M.P.-F. and F.M.; supervision, M.P.-F. and F.M.; project administration, M.P.-F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors have not received any funding or benefits from the industry or else-where to conduct this study.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística. Coyuntura Demográfica de Empresas (CODEM); Experimental; Instituto Nacional de Estadís-tica: Madrid, Spain, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- European Union Commission. Green Paper: Unlocking the Potential of Cultural and Creative Industries. Brussels 2010, 183. Available online: https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/1cb6f484-074b-4913-87b3-344ccf020eef/language-en (accessed on 28 December 2021).

- Zahra, S.A.; Sapienza, H.J.; Davidsson, P. Entrepreneurship and Dynamic Capabilities: A Review, Model and Research Agenda. J. Manag. Stud. 2006, 43, 917–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teece, D.J. Explicating Dynamic Capabilities: The Nature and Micro Foundations of (Sustainable) Enterprise Performance. Strateg. Manag. J. 2007, 28, 1319–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dottore, A.G. Business Model Adaptation as a Dynamic Capability: A Theoretical Lens for Observing Practitioner Behaviour. In Proceedings of the 22nd Bled EConference EEnablement: Facilitating an Open, Effective and Representative ESociety, Bled, Slovenia, 14–17 June 2009; No. Lerner 1995, pp. 484–505. [Google Scholar]

- Saebi, T. Business Model Evolution, Adaptation or Innovation? A Contingency Framework on Business Model Dynamics, Environmental Change and Dynamic Capabilities; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2014; Volume 1, pp. 1625–1678. [Google Scholar]

- Zott, C.; Amit, R. Business Model Design and the Performance of Entrepreneurial Firms. Organ. Sci. 2007, 18, 181–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glaser, B.; Strauss, A. The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research; Aldine de Gruyter: Hawthorne, NY, USA, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Noble, H.; Mitchell, G. What Is Grounded Theory? Evid. Based Nurs. 2016, 19, 34–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osterwalder, A.; Pigneur, Y. Business Model Generation: A Handbook for Visionaries, Game Changers, and Challengers; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2010; Available online: https://books.google.es/books?id=L3TnC7ZAWAsC&dq=building+a+business+model+osterwalder+%22free+as+a+business+model%22&hl=es&source=gbs_navlinks_s (accessed on 17 March 2019).

- Casadesus-Masanell, R.; Zhu, F. Business Model Innovation and Competitive Imitation: The Case of Sponsor-Based Business Models. Strateg. Manag. J. 2013, 34, 464–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chesbrough, H. Business Model Innovation: Opportunities and Barriers. Long Range Plann. 2010, 43, 354–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wirtz, B.W.; Göttel, V.; Daiser, P. Business Model Innovation: Development, Concept and Future Research Directions. J. Bus. Model. 2016, 4, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amit, R.H.; Massa, L.; Zott, C. The Business Model: Recent Developments and Future Research. J. Manag. 2011, 37, 1019–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peñarroya-Farell, M.; Miralles, F. Business Model Dynamics from Interaction with Open Innovation. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2021, 7, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saebi, T.; Lien, L.; Foss, N.J. What Drives Business Model Adaptation? The Impact of Opportunities, Threats and Strategic Orientation. Long Range Plann. 2017, 50, 567–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foss, N.J.; Saebi, T. Fifteen Years of Research on Business Model Innovation. J. Manag. 2017, 43, 200–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landau, C.; Karna, A.; Sailer, M. Business Model Adaptation for Emerging Markets: A Case Study of a German Automobile Manufacturer in India. R&d Manag. 2016, 46, 480–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snihur, Y.; Thomas, L.D.W.; Burgelman, R.A. An Ecosystem-Level Process Model of Business Model Disruption: The Disruptor’s Gambit. J. Manag. Stud. 2018, 55, 1278–1316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavalcante, S.; Kesting, P.; Ulhøi, J. Business Model Dynamics and Innovation: Re-Establishing the Missing Linkages. Manag. Decis. 2011, 49, 1327–1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolkamp, J.; Huijben, J.C.C.M.; Mourik, R.M.; Verbong, G.P.J.; Bouwknegt, R. User-Centred Sustainable Business Model Design: The Case of Energy Efficiency Services in the Netherlands. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 182, 755–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chesbrough, H. Open Business Models: How to Thrive in the New Innovation Landscape. 2006. Available online: https://books.google.es/books?hl=en&lr=&id=MWPlLbULAmwC&oi=fnd&pg=PT3&ots=BHqJW1jrcQ&sig=GhLDZs6C_KnVbO_VwFg4w8629_0&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q&f=false (accessed on 13 February 2021).

- Weiblen, T. The Open Business Model: Understanding an Emerging Concept. J. Multi. Bus. Model Innov. Technol. 2016, 2, 35–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saebi, T.; Foss, N.J. Business Models for Open Innovation: Matching Heterogenous Open Innovation Strategies. Eur. Manag. J. 2015, 33, 201–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chesbrough, H. The Future of Open Innovation: IRI Medal AddressThe Future of Open Innovation Will Be More Extensive, More Collaborative, and More Engaged with a Wider Variety of Participants. Res. Technol. Manag. 2017, 60, 29–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chesbrough, H.; Bogers, M. Explicating Open Innovation: Clarifying an Emerging Paradigm for Understanding Innovation Keywords. New Front. Open Innov. 2014, 15, 1–37. [Google Scholar]

- Yun, J.J. Business Model Design Compass; Management for Professionals; Springer: Singapore, 2017; Available online: http://link.springer.com/10.1007/978-981-10-4128-0 (accessed on 19 February 2021).

- Feller, J.; Finnegan, P.; Nilsson, O. Open Innovation and Public Administration: Transformational Typologies and Business Model Impacts. Eur. J. Inf. Syst. 2011, 20, 358–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenhardt, K.M.; Martin, J.A. Dynamic Capabilities: What Are They? Strateg. Manag. J. 2000, 21, 1105–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Regan, N.; Ghobadian, A. The Importance of Capabilities for Strategic Direction and Performance. Manag. Decis. 2004, 42, 292–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amit, R.; Zott, C. Value Creation in E-Business. Strateg. Manag. J. 2001, 22, 493–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demil, B.; Lecocq, X. Business Model Evolution: In Search of Dynamic Consistency. Long Range Plann. 2010, 43, 227–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inan, G.G.; Bititci, U.S. Understanding Organizational Capabilities and Dynamic Capabilities in the Context of Micro Enterprises: A Research Agenda. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 210, 310–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teece, D.J. The Foundations of Enterprise Performance: Dynamic and Ordinary Capabilities in an (Economic) Theory of Firms. Acad. Manag. Perspect. 2014, 28, 328–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winter, S.G. Understanding Dynamic Capabilities. Strateg. Manag. J. 2003, 24, 991–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darin, C.; Training, R.O.; Kimberly, M.; Deepa, G.; Board, E.; Principal, E.; Primary, I.; Systems, F.; Study, E.B.; Co-investigator, N. Emergency Management, 3rd ed.; 2014; No. 1; pp. 1–5. Available online: https://www.mendeley.com/catalogue/8c8291b0-4e62-357a-85ab-a13848128a26/?utm_source=desktop&utm_medium=1.19.4&utm_campaign=open_catalog&userDocumentId=%7B565256f4-ba0d-4059-b19f-33c46a047e3c%7D (accessed on 8 January 2021).

- Jensen, J. The Argument for a Disciplinary Approach to Emergency Management Higher Education. 2010. Available online: http://training.fema.gov/EMIWeb/edu/highpapers.asp (accessed on 28 December 2021).

- Moorman, C.; Miner, A.S. The Convergence of Planning and Execution: Improvisation in New Product Development. J. Mark. 2018, 62, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villar, E.B.; Miralles, F. Purpose-Driven Improvisation during Organisational Shocks: Case Narrative of Three Critical Organisations and Typhoon Haiyan. Disasters 2021, 45, 477–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kung, L. Organization Improvisational Capability and Configurations of Firm Performance in a Highly Turbulent Environment. Ph.D. Thesis, Auburn Univeristy, Auburn, AL, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Rezaei, B.; Delangizan, S.; Khodaei, A. Business Environment: Designing and Explaining the New Environmental Hostility Model in Small and Medium Enterprises. J. Syst. Manag. 2020, 6, 1–29. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research: Design and Methods (Applied Social Research Methods), 2nd ed.; Methods Series; SAGE: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1994; p. 312. [Google Scholar]

- Corbin, J.; Strauss, A. Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory, 3rd ed.; SAGE Publications: Southend Oaks, CA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Kincheloe, J.L.; Mclaren, P. Rethinking Critical Theory and Qualitative Research. Key Work. Crit. Pedagog. 2011, 285–326. Available online: https://psycnet.apa.org/record/1994-98625-007 (accessed on 30 May 2021).

- Miles, B.W.; Jozefowicz-Simbeni, D.M.H. Naturalistic Inquiry. In The Handbook of Social Work Research Methods; SAGE Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2019; pp. 415–424. [Google Scholar]

- Galloway, J.A.; Sheridan, S.M. Implementing Scientific Practices through Case Studies: Examples Using Home-School Interventions and Consultation. J. Sch. Psychol. 1994, 32, 385–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Eisenhardt, K.M. Building Theories from Case Study Research. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1989, 8, 2–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkassim, R.S.; Tran, X.; Rivera, J.D.; Etikan, I.; Abubakar Musa, S.; Sunusi Alkassim, R. Comparison of Convenience Sampling and Purposive Sampling. Am. J. Theor. Appl. Stat. 2016, 5, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viaene, S.; Broeckx, S. How IT Enables Business Model Innovation at the VDAB. J. Inf. Technol. Teach. Cases 2013, 3, 78–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faissal Bassis, N.; Armellini, F. Systems of Innovation and Innovation Ecosystems: A Literature Review in Search of Complementarities. J. Evol. Econ. 2018, 28, 1053–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodard, C.J.; Ramasubbu, N.; Tschang, F.T.; Sambamurthy, V. Design Capital and Design Moves: The Logic of Digital Business Strategy. Mis Q. 2012, 537–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGrath, R.; MacMillan, I.C. Discovery-Driven Growth Seize Opportunity. A Breackthrough Provess to Reduce Risk and Seize Opportunity; Harvard Business Press: Boston, MA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Passerini, E. Disasters as Agents of Social Change in Recovery and Reconstruction. Nat. Hazards Rev. 2000, 1, 67–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The Theory of Planned Behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlou, P.A.; El Sawy, O.A. It-Enabled Business Capabilities for Turbulent Environments. SSRN Electron. J. 2013, 2003, 1–35. [Google Scholar]

- He, H.; Bai, Y.; Gao, J.; Xie, J. How R&D Staff’s Improvisation Capability Is Formed: A Perspective of Micro-Foundations. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 2337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akpan, I.J.; Soopramanien, D.; Kwak, D.H. Cutting-Edge Technologies for Small Business and Innovation in the Era of COVID-19 Global Health Pandemic. J. Small Bus. Entrep. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webb, G.R.; Chevreau, F.R. Planning to Improvise: The Importance of Creativity and Flexibility in Crisis Response. Int. J. Emerg. Manag. 2006, 3, 66–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Druker, P. The New Realities: In Government and Politics, in Economics and Business, in Society and World View. Choice Rev. Online 1989, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, P.; Camp, M.; Bygrave, W.; Autio, E.; Hay, M. Global Entrepreneurship Monitor 2001 Executive Report. 2001. Available online: https://research.aalto.fi/en/publications/global-entrepreneurship-monitor-2001-executive-report (accessed on 10 August 2021).

- Zhang, B.; Wang, H. Network Proximity Evolution of Open Innovation Diffusion: A Case of Artificial Intelligence for Healthcare. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2021, 7, 222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferras-Hernandez, X.; Nylund, P.A. Clusters as Innovation Engines: The Accelerating Strengths of Proximity. Eur. Manag. Rev. 2019, 16, 37–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiuma, G.; Lerro, A. The Business Model Prism: Managing and Innovating Business Models of Arts and Cultural Organisations. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2017, 3, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmi, P.; Madaro, L. Business Model Innovation through Digitalization in Cultural Organizations: The Case of Maxxi. In Cultural Management and Policy in a Post-Digital World—Navigating Uncertainty Introduction; 2020; pp. 95–115. Available online: https://iris.unisalento.it/handle/11587/445247 (accessed on 10 August 2021).

- Ernst, D.; Adams, R.; Esche, C.; Erbslöh, U. Business Model Innovation: Cultural Venues as Laboratories, Art as the Tool. In R&D Management—(Fast?) Connecting R&D; 2015; Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/275256489_Business_model_innovation_cultural_venues_as_laboratories_art_as_the_tool (accessed on 10 August 2021).

- Popescu, C.R.G. Sustainability Assessment: Does the OECD/G20 Inclusive Framework for BEPS (Base Erosion and Profit Shifting Project) Put an End to Disputes Over The Recognition and Measurement of Intellectual Capital? Sustainability 2020, 12, 10004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).