Using Online Grocery Applications during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Their Relationship with Open Innovation

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Review of Related Literature

2.1. Technology Acceptance Model (TAM)

2.2. Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology (UTAUT2)

2.3. Health Belief Model (HBM)

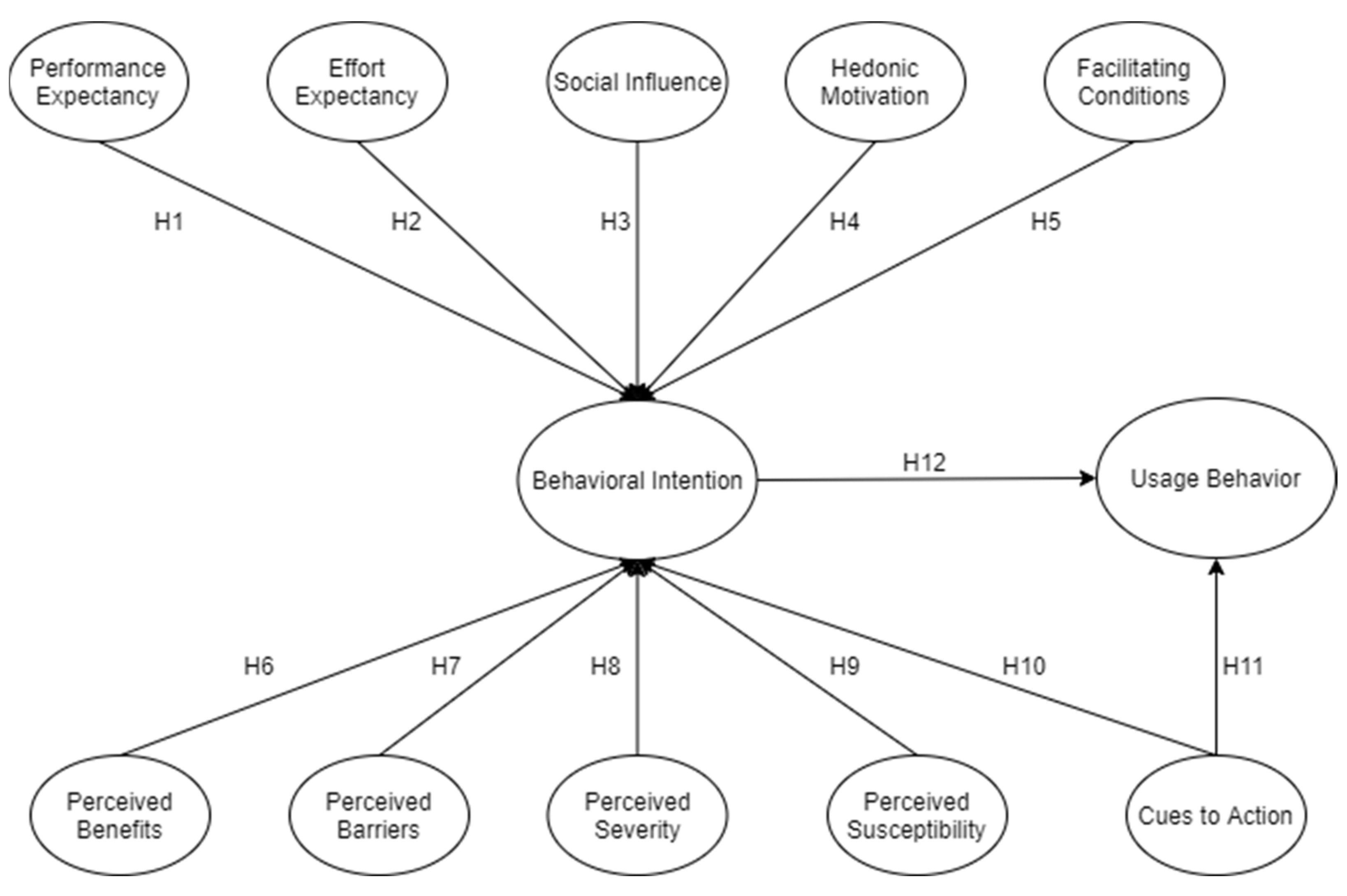

3. Conceptual Framework

3.1. Determinants of Behavioral Intentions and Usage of Online Grocery Apps Based on the UTAUT2 Model

3.2. The Determinants of Behavioral Intentions and the Usage of Online Grocery Apps Based on the Health Belief Model

4. Methodology

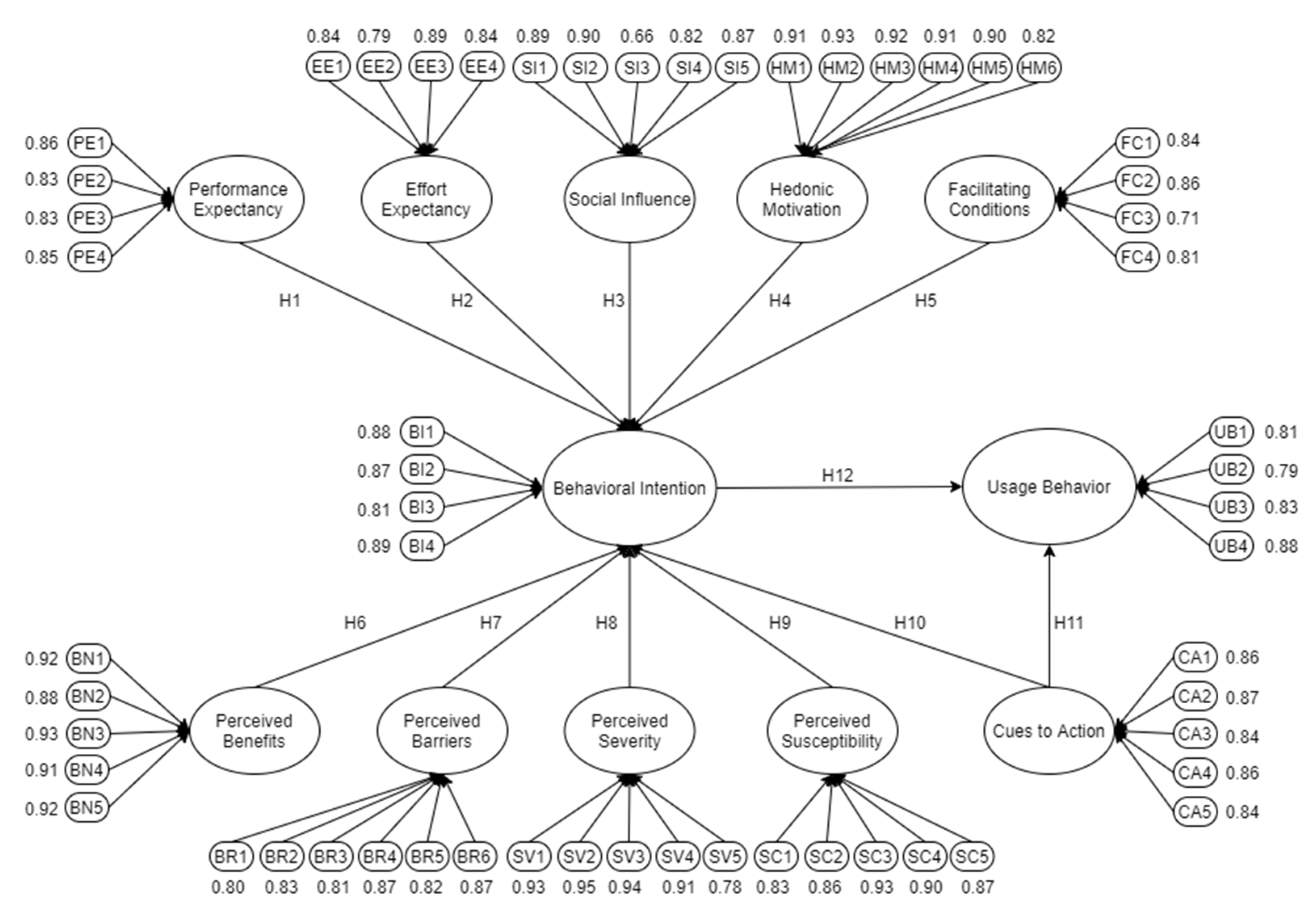

4.1. Measurement

4.2. Questionnaire

4.3. Structural Equation Modeling

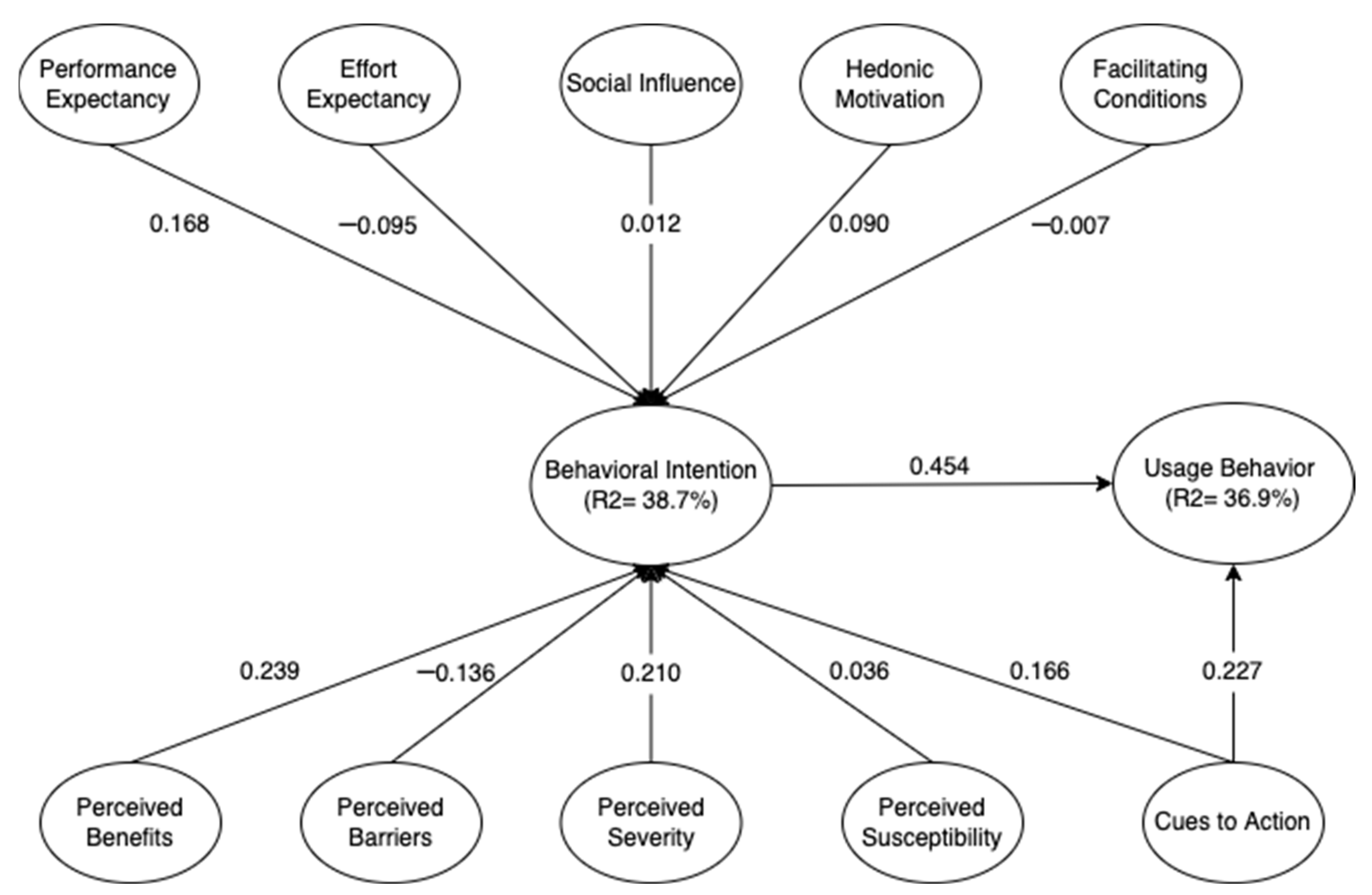

5. Results

6. Discussion

6.1. The Intention to Use Online Grocery Applications during the COVID-19 Pandemic

6.2. The Relationship between Using Online Applications and Open Innovation

7. Conclusions

7.1. Practical and Managerial Implication

7.2. Theoretical Implication

7.3. Limits and Future Research Topics

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Coppola, D. E-Commerce Worldwide—Statistics & Facts. Available online: https://www.statista.com/topics/871/online-shopping/ (accessed on 20 May 2021).

- Chevalier, S. Global Retail e-Commerce Sales 2014–2024. Available online: https://www.statista.com (accessed on 20 May 2021).

- Store, G.R. Company Insight—Top 50 Global Online Retailers 2019. Available online: https://store.globaldata.com/report/gdrt00012rl--company-insight-top-50-global-online-retailers-2019/ (accessed on 20 May 2021).

- Institute, F.M. The e-Tail Experience: What Grocery Shoppers Think about Online Shopping 2000—Executive Summary. Available online: http://www.fmi.org/e_business.etailexperience.htm (accessed on 20 May 2021).

- Saunders, N. Online Grocery & Food Shopping Statistics. Available online: https://www.onespace.com/blog/2018/08/online-grocery-food-shopping-statistics/ (accessed on 28 May 2021).

- Alaimo, L.S.; Fiore, M.; Galati, A. How the COVID-19 pandemic is changing online food shopping human behaviour in Italy. Sustainability 2020, 12, 9594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Efrati, A. Instacart Swings to First Profit as Pandemic Fuels Surge in Grocery Delivery. Available online: https://www.theinformation.com/articles/instacart-swings-to-first-profit-as-pandemic-fuels-surgein-grocery-delivery (accessed on 27 April 2021).

- Kamiak, M.; Fox, M. Online Grocery Shopping: Consumer Motives, Concerns, and Business Models. Available online: http://firstmonday.org/issues/issue7_9/fox/index.html (accessed on 20 May 2021).

- Adalid, A. Top Online Grocery Delivery Manila Sites & Apps (Philippines). Available online: https://iamaileen.com/grocery-delivery-manila/ (accessed on 20 May 2021).

- Davis, F.D. Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology. MIS Q. 1989, 13, 319–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Driediger, F.; Bhatiasevi, V. Online grocery shopping in Thailand: Consumer acceptance and usage behavior. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2019, 48, 224–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kian, T.P.; Loong, A.C.W.; Fong, S.W.L. Customer purchase intention on online grocery shopping. Int. J. Acad. Res. Bus. Soc. Sci. 2018, 8, 1579–1595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bauerová, R.; Klepek, M. Technology acceptance as a determinant of online grocery shopping adoption. Acta Univ. Agric. Silvic. Mendel. Brun. 2018, 66, 737–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Charness, N.; Boot, W.R. Technology, gaming, and social networking. In Handbook of the Psychology of Aging; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2016; pp. 389–407. [Google Scholar]

- Ain, N.; Kaur, K.; Waheed, M. The influence of learning value on learning management system use: An extension of UTAUT2. Inf. Dev. 2016, 32, 1306–1321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V.; Thong, J.Y.; Xu, X. Consumer acceptance and use of information technology: Extending the unified theory of acceptance and use of technology. MIS Q. 2012, 36, 157–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Van Droogenbroeck, E.; Van Hove, L. Adoption and usage of E-grocery shopping: A context-specific UTAUT2 model. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Human, G.; Ungerer, M.; Azémia, J.-A.J. Mauritian consumer intentions to adopt online grocery shopping: An extended decomposition of UTAUT2 with moderation. Manag. Dyn. J. South. Afr. Inst. Manag. Sci. 2020, 29, 15–37. [Google Scholar]

- LaMorte, W. The Health Belief Model. Available online: https://sphweb.bumc.bu.edu/otlt/mphmodules/sb/behavioralchangetheories/behavioralchangetheories2.html (accessed on 20 May 2021).

- Chua, G.; Yuen, K.F.; Wang, X.; Wong, Y.D. The Determinants of Panic Buying during COVID-19. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 3247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahnazi, H.; Ahmadi-Livani, M.; Pahlavanzadeh, B.; Rajabi, A.; Hamrah, M.S.; Charkazi, A. Assessing preventive health behaviors from COVID-19: A cross sectional study with health belief model in Golestan Province, Northern of Iran. Infect. Dis. Poverty 2020, 9, 91–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walrave, M.; Waeterloos, C.; Ponnet, K. Ready or not for contact tracing? Investigating the adoption intention of COVID-19 contact-tracing technology using an extended unified theory of acceptance and use of technology model. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 2021, 24, 377–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloomberg. Why the Philippines Just Became the Worst Place to be in Covid. Available online: https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2021-09-29/why-the-philippines-just-became-the-worst-place-to-be-in-covid (accessed on 20 May 2021).

- OECD. E-Commerce in the Time of Covid-19. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/coronavirus/policy-responses/e-commerce-in-the-time-of-covid-19-3a2b78e8/ (accessed on 2 December 2021).

- Loxton, M.; Truskett, R.; Scarf, B.; Sindone, L.; Baldry, G.; Zhao, Y. Consumer Behaviour during Crises: Preliminary Research on How Coronavirus Has Manifested Consumer Panic Buying, Herd Mentality, Changing Discretionary Spending and the Role of the Media in Influencing Behaviour. J. Risk Financ. Manag. 2020, 13, 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Meara, L.; Turner, C.; Coitinho, D.C.; Oenema, S. Consumer experiences of food environments during the Covid-19 pandemic: Global insights from a rapid online survey of individuals from 119 countries. Glob. Food Secur. 2021, 32, 100594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Venkatesh, V.; Morris, M.G.; Davis, G.B.; Davis, F.D. User acceptance of information technology: Toward a unified view. MIS Q. 2003, 27, 425–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tong, K.K.; Chen, J.H.; Yu, E.W.y.; Wu, A.M. Adherence to COVID-19 Precautionary Measures: Applying the Health Belief Model and Generalised Social Beliefs to a Probability Community Sample. Appl. Psychol. Health Well-Being 2020, 12, 1205–1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Sabbagh, M.Q.; Al-Ani, A.; Mafrachi, B.; Siyam, A.; Isleem, U.; Massad, F.I.; Alsabbagh, Q.; Abufaraj, M. Predictors of adherence with home quarantine during COVID-19 crisis: The case of health belief model. Psychol. Health Med. 2021, 27, 215–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharifikia, I.; Rohani, C.; Estebsari, F.; Matbouei, M.; Salmani, F.; Hossein-Nejad, A. Health belief model-based intervention on women’s knowledge and perceived beliefs about warning signs of cancer. Asia-Pac. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2019, 6, 431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qureshi, I.; Fang, Y.; Ramsey, E.; McCole, P.; Ibbotson, P.; Compeau, D. Understanding online customer repurchasing intention and the mediating role of trust–an empirical investigation in two developed countries. Eur. J. Inf. Syst. 2009, 18, 205–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chopdar, P.K.; Korfiatis, N.; Sivakumar, V.; Lytras, M.D. Mobile shopping apps adoption and perceived risks: A cross-country perspective utilizing the Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2018, 86, 109–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lai, I.K.; Lai, D.C. User acceptance of mobile commerce: An empirical study in Macau. Int. J. Syst. Sci. 2014, 45, 1321–1331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.-M.; Liu, L.-W.; Huang, H.-C.; Hsieh, H.-H. Factors influencing online hotel booking: Extending UTAUT2 with age, gender, and experience as moderators. Information 2019, 10, 281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sun, S.; Lou, Y.; Chao, P.; Wu, C. A study on the factors influencing the users’ intention in human recruiting sites. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2008, 8, 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Moore, G.C.; Benbasat, I. Development of an instrument to measure the perceptions of adopting an information technology innovation. Inf. Syst. Res. 1991, 2, 192–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Brown, S.A.; Venkatesh, V. Model of adoption of technology in households: A baseline model test and extension incorporating household life cycle. MIS Q. 2005, 29, 399–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thong, J.Y.; Hong, S.-J.; Tam, K.Y. The effects of post-adoption beliefs on the expectation-confirmation model for information technology continuance. Int. J. Hum. -Comput. Stud. 2006, 64, 799–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, T.; Faria, M.; Thomas, M.A.; Popovič, A. Extending the understanding of mobile banking adoption: When UTAUT meets TTF and ITM. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2014, 34, 689–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tak, P.; Panwar, S. Using UTAUT2 model to predict mobile app based shopping: Evidences from India. J. Indian Bus. Res. 2017, 9, 248–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alwahaishi, S.; Snášel, V. Consumers’ acceptance and use of information and communications technology: A UTAUT and flow based theoretical model. J. Technol. Manag. Innov. 2013, 8, 61–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Susanto, P.; Abdullah, N.L.; Rela, I.Z.; Wardi, Y. Understanding e-money adoption: Extending the unified theory of acceptance and use of technology (UTAUT). Int. J. Appl. Bus. Econ. Res. 2017, 15, 335–345. [Google Scholar]

- Boskey, E. How the Health Belief Model Influences Your Health Choices. Available online: https://www.verywellmind.com/health-belief-model-3132721 (accessed on 20 May 2021).

- Mirzaei, M.; Mirzaei, M.; Mirzaei, M.; Bagheri, B. Changes in the prevalence of measures associated with hypertension among Iranian adults according to classification by ACC/AHA guideline 2017. BMC Cardiovasc. Disord. 2020, 20, 372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. COVID-19 High Risk Groups. Available online: https://www.who.int/westernpacific/emergencies/covid-19/information/high-risk-groups#:~:text=COVID%2D19%20is%20often%20more%20severe%20in%20people%2060%2Byrs,who%20are%20at%20most%20risk (accessed on 2 December 2021).

- Pandey, N.; Pal, A. Impact of digital surge during Covid-19 pandemic: A viewpoint on research and practice. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2020, 55, 102171. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, C.-Y.; Tang, C.S.-K. Practice of habitual and volitional health behaviors to prevent severe acute respiratory syndrome among Chinese adolescents in Hong Kong. J. Adolesc. Health 2005, 36, 193–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kwok, K.O.; Li, K.-K.; Chan, H.; Yi, Y.Y.; Tang, A.; Wei, W.I.; Wong, Y. Community response during the early phase of COVID 19 epidemic in Hong Kong: Risk perception, information exposure and preventive measures. MedRxiv 2020, 26, 1574. [Google Scholar]

- Qian, M.; Wu, Q.; Wu, P.; Hou, Z.; Liang, Y.; Cowling, B.J.; Yu, H. Anxiety levels, precautionary behaviours and public perceptions during the early phase of the COVID-19 outbreak in China: A population-based cross-sectional survey. BMJ Open 2020, 10, e040910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, S.; Todd, P.A. Understanding information technology usage: A test of competing models. Inf. Syst. Res. 1995, 6, 144–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamane, T. Statistics: An Introductory Analysis; Harper & Row: Manhattan, NY, USA, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Bae, S.; Lee, T. Gender differences in consumers’ perception of online consumer reviews. Electron. Commer. Res. 2011, 11, 201–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.; Lester, D. Gender differences in e-commerce. Appl. Econ. 2005, 37, 2077–2089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Wu, C.C. Gender differences in online shoppers’ decision-making styles. In e-Business and Telecommunication Networks; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2006; pp. 108–115. [Google Scholar]

- Gutierrez, B.P.B.; Jegasothy, K. Identifying shopping problems and improving retail patronage among urban filipino customers. Philipp. Manag. Rev. 2010, 17, 66–79. [Google Scholar]

- Macdonald, C. Study: Men Now Shop for Groceries as often as Women. Available online: https://www.fooddive.com/news/study-men-now-shop-for-groceries-as-often-as-women/441187/ (accessed on 2 December 2021).

- Prasetyo, Y.T.; Roque, R.A.C.; Chuenyindee, T.; Young, M.N.; Diaz, J.F.T.; Persada, S.F.; Miraja, B.A.; Perwira Redi, A.A.N. Determining Factors Affecting the Acceptance of Medical Education eLearning Platforms during the COVID-19 Pandemic in the Philippines: UTAUT2 Approach. Healthcare 2021, 9, 780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, S.; Ma, W.; Kanthawala, S.; Peng, W. Keep using my health apps: Discover users’ perception of health and fitness apps with the UTAUT2 model. Telemed. E-Health 2015, 21, 735–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tadesse, T.; Alemu, T.; Amogne, G.; Endazenaw, G.; Mamo, E. Predictors of Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) prevention practices using health belief model among employees in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Infect. Drug Resist. 2020, 13, 3751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuen, K.F.; Li, K.X.; Ma, F.; Wang, X. The effect of emotional appeal on seafarers’ safety behaviour: An extended health belief model. J. Transp. Health 2020, 16, 100810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bechard, L.E.; Bergelt, M.; Neudorf, B.; DeSouza, T.C.; Middleton, L.E. Using the Health Belief Model to Understand Age Differences in Perceptions and Responses to the COVID-19 Pandemic. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamran, K.; Ali, A.; Villagra, C.; Siddiqui, S.; Alouffi, A.S.; Iqbal, A. A cross-sectional study of hard ticks (acari: Ixodidae) on horse farms to assess the risk factors associated with tick-borne diseases. Zoonoses Public Health 2021, 68, 247–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bults, M.; Beaujean, D.J.; Richardus, J.H.; Voeten, H.A. Perceptions and behavioral responses of the general public during the 2009 influenza A (H1N1) pandemic: A systematic review. Disaster Med. Public Health Prep. 2015, 9, 207–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Sarstedt, M.; Ringle, C.M.; Mena, J.A. An assessment of the use of partial least squares structural equation modeling in marketing research. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2012, 40, 414–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dash, G.; Paul, J. CB-SEM vs PLS-SEM methods for research in Social Sciences and Technology forecasting. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2021, 173, 121092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouellette, J.A.; Wood, W. Habit and intention in everyday life: The multiple processes by which past behavior predicts future behavior. Psychol. Bull. 1998, 124, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.-t.; Bentler, P.M. Fit indices in covariance structure modeling: Sensitivity to underparameterized model misspecification. Psychol. Methods 1998, 3, 424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumgartner, H.; Homburg, C. Applications of structural equation modeling in marketing and consumer research: A review. Int. J. Res. Mark. 1996, 13, 139–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Alarcón, D.; Sánchez, J.A.; De Olavide, U. Assessing convergent and discriminant validity in the ADHD-R IV rating scale: User-written commands for Average Variance Extracted (AVE), Composite Reliability (CR), and Heterotrait-Monotrait ratio of correlations (HTMT). In Proceedings of the Spanish STATA Meeting, Madrid, Spain, 22 October 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Bradley, J.V. Robustness? Br. J. Math. Stat. Psychol. 1978, 31, 144–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A new criterion for assessing discriminant validity in variance-based structural equation modeling. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2015, 43, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dijkstra, T.K.; Henseler, J. Consistent and asymptotically normal PLS estimators for linear structural equations. Comput. Stat. Data Anal. 2015, 81, 10–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Venkatesh, V.; Davis, F.D. A theoretical extension of the technology acceptance model: Four longitudinal field studies. Manag. Sci. 2000, 46, 186–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chong, A.Y.-L. A two-staged SEM-neural network approach for understanding and predicting the determinants of m-commerce adoption. Expert Syst. Appl. 2013, 40, 1240–1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, K.; Kim, H.Y. Mobile shopping motivation: An application of multiple discriminant analysis. Int. J. Retail Distrib. Manag. 2012, 40, 778–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piarna, R.; Fathurohman, F.; Purnawan, N.N. Understanding online shopping adoption: The unified theory of acceptance and the use of technology with perceived risk in millennial consumers context. JEMA J. Ilmiaj Bid. Akunt. Dan Manaj. 2020, 17, 51–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Warganegara, D.L.; Babolian Hendijani, R. Factors that drive actual purchasing of groceries through e-commerce platforms during COVID-19 in Indonesia. Sustainability 2022, 14, 3235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erjavec, J.; Manfreda, A. Online shopping adoption during COVID-19 and social isolation: Extending the UTAUT model with herd behavior. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2022, 65, 102867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habib, S.; Hamadneh, N.N. Impact of perceived risk on consumers technology acceptance in online grocery adoption amid covid-19 pandemic. Sustainability 2021, 13, 10221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naeem, M.; Ozuem, W. The role of social media in internet banking transition during COVID-19 pandemic: Using multiple methods and sources in qualitative research. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2021, 60, 102483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikheev, A.A.; Krasnov, A.; Griffith, R.; Draganov, M. The interaction model within Phygital environment as an implementation of the open innovation concept. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2021, 7, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turoń, K. Open innovation business model as an opportunity to enhance the development of sustainable shared mobility industry. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2022, 8, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valdez-Juárez, L.E.; Gallardo-Vázquez, D.; Ramos-Escobar, E.A. Online buyers and open innovation: Security, experience, and satisfaction. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2021, 7, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Illescas-Manzano, M.D.; Vicente López, N.; Afonso González, N.; Cristofol Rodríguez, C. Implementation of chatbot in online commerce, and open innovation. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2021, 7, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van de Vrande, V.; de Jong, J.P.J.; Vanhaverbeke, W.; de Rochemont, M. Open innovation in smes: Trends, Motives and Management Challenges. Technovation 2009, 29, 423–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yun, J.H.J.; Won, D.K.; Park, K.B. Entrepreneurial cyclical dynamics of open innovation. J. Evol. Econ. 2018, 28, 1151–1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolton, R.; Gustafsson, A.; McColl-Kennedy, J.J.; Sirianni, N.; Tse, D.K. Small details that make big differences. J. Serv. Manag. 2014, 25, 253–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pilawa, J.; Witell, L.; Valtakoski, A.; Kristensson, P. Service innovativeness in retailing: Increasing the relative attractiveness during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2022, 67, 102962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasetyo, Y.T.; Tanto, H.; Mariyanto, M.; Hanjaya, C.; Young, M.N.; Persada, S.F.; Miraja, B.A.; Redi, A.A. Factors affecting customer satisfaction and loyalty in online food delivery service during the COVID-19 pandemic: Its relation with open innovation. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2021, 7, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, S.-L.; Goh, Y.-N. Consumer Purchase Intention Toward Online Grocery Shopping: View from Malaysia. Glob. Bus. Manag. Res. Int. J. 2017, 9, 221–238. [Google Scholar]

- Balinado, J.R.; Prasetyo, Y.T.; Young, M.N.; Persada, S.F.; Miraja, B.A.; Perwira Redi, A.A. The effect of service quality on customer satisfaction in an automotive after-sales service. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2021, 7, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- German, J.D.; Redi, A.A.; Prasetyo, Y.T.; Persada, S.F.; Ong, A.K.; Young, M.N.; Nadlifatin, R. Choosing a package carrier during COVID-19 pandemic: An integration of pro-environmental planned behavior (PEPB) theory and Service Quality (SERVQUAL). J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 346, 131123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasetyo, Y.T.; Dewi, R.S.; Balatbat, N.M.; Antonio, M.L.; Chuenyindee, T.; Perwira Redi, A.A.; Young, M.N.; Diaz, J.F.; Kurata, Y.B. The evaluation of preference and perceived quality of health communication icons associated with covid-19 prevention measures. Healthcare 2021, 9, 1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Author | Year | Theory | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Driediger & Bhatiasevi [11] | 2019 | TAM | There is a statistically significant link between the subjective norm, risk perception, fun and enjoyment, and visibility with online grocery buying acceptability. |

| Kian et al. [12] | 2018 | Extended TAM | The most critical factor impacting consumers’ purchase intentions on online grocery shopping apps is social influence, while perceived ease of use is an insignificant factor. |

| Bauerova & Klepek [13] | 2018 | Extended TAM | Perceived utility and convenience of use directly impact behavioral intentions on online grocery apps. |

| Van Droogenbroeck & Van Hove [17] | 2021 | Extended UTAUT2 | Perceived time pressure and innovativeness are identified drivers of behavioral intentions to use e-grocery services. |

| Human et al. [18] | 2020 | Extended UTAUT2 | Social influence, effort expectancy, facilitating conditions, perceived trust, and perceived risk do not significantly influence behavioral intentions to use online groceries. |

| Chua et al. [20] | 2021 | HBM | Consumers’ perceptions of product scarcity play a role in panic buying during the COVID-19 pandemic. |

| Shahnazi et al. [21] | 2020 | HBM | Perceived barriers, self-efficacy, interests, and fatalistic beliefs significantly influence COVID-19 preventative actions. |

| Walrave et al. [22] | 2021 | HBM | The perceived advantages of the COVID-19 app are found to be the strongest indicator for the acceptance of the contract tracing app, followed by self-efficacy and perceived barriers. |

| Characteristics | Category | N | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Female | 226 | 61% |

| Male | 147 | 39% | |

| Total | 373 | 100% | |

| Age | 20 and below | 51 | 14% |

| 21–30 | 92 | 25% | |

| 31–40 | 128 | 34% | |

| 41–50 | 95 | 25% | |

| 51 and above | 7 | 2% | |

| Total | 373 | 100% | |

| Education | Finished college or with a graduate degree | 194 | 52% |

| Attended college | 117 | 31% | |

| Attended high school | 59 | 16% | |

| Attended at least grade school level | 3 | 1% | |

| Total | 373 | 100% | |

| Residential | City | 254 | 68% |

| Province | 119 | 32% | |

| Total | 373 | 100% | |

| No. of members in the family | 1–2 | 33 | 9% |

| 3–4 | 146 | 39% | |

| 5 or more | 194 | 52% | |

| Total | 373 | 100% | |

| Household monthly income (PHP) | Less than 40,000 | 35 | 9% |

| 40,001–70,000 | 84 | 23% | |

| 70,001–100,000 | 60 | 16% | |

| 100,001–130,000 | 111 | 30% | |

| More than 130,000 | 83 | 22% | |

| Total | 373 | 100% | |

| Frequency of buying grocery | Once a week | 90 | 24% |

| Twice a month | 161 | 43% | |

| Once a month | 91 | 24% | |

| Less than once a month | 31 | 8% | |

| Total | 373 | 100% | |

| Monthly grocery expense | Less than PHP 2000 | 41 | 11% |

| PHP 2001-PHP 5000 | 78 | 21% | |

| PHP 5001–PHP 8000 | 75 | 20% | |

| PHP 8001–PHP 11,000 | 96 | 26% | |

| PHP 11,001–PHP 14,000 | 36 | 10% | |

| PHP 14,000 and above | 47 | 13% | |

| Total | 373 | 100% | |

| Mode of payment in buying groceries | Cash basis | 235 | 63% |

| Credit card basis | 138 | 37% | |

| Total | 373 | 100% |

| Total Household Income in a Month | Gender | Total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female | Male | ||||

| less than PHP 40,000 | Age Range | 20 and below | 1 | 4 | 5 |

| 21–30 | 6 | 0 | 6 | ||

| 31–40 | 11 | 4 | 15 | ||

| 41–50 | 7 | 1 | 8 | ||

| 51 and above | 0 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Total | 25 | 10 | 35 | ||

| PHP 40,001–PHP 70,000 | Age Range | 20 and below | 7 | 5 | 12 |

| 21–30 | 16 | 9 | 25 | ||

| 31–40 | 19 | 11 | 30 | ||

| 41–50 | 12 | 5 | 17 | ||

| Total | 54 | 30 | 84 | ||

| PHP 70,001–PHP 100,000 | Age Range | 20 and below | 0 | 5 | 5 |

| 21–30 | 13 | 7 | 20 | ||

| 31–40 | 7 | 9 | 16 | ||

| 41–50 | 16 | 2 | 18 | ||

| 51 and above | 0 | 1 | 1 | ||

| Total | 36 | 24 | 60 | ||

| PHP 100,001–PHP 130,000 | Age Range | 20 and below | 5 | 7 | 12 |

| 21–30 | 15 | 9 | 24 | ||

| 31–40 | 24 | 18 | 42 | ||

| 41–50 | 21 | 9 | 30 | ||

| 51 and above | 1 | 2 | 3 | ||

| Total | 66 | 45 | 111 | ||

| more than PHP 130,000 | Age Range | 20 and below | 6 | 11 | 17 |

| 21–30 | 11 | 6 | 17 | ||

| 31–40 | 10 | 15 | 25 | ||

| 41–50 | 17 | 5 | 22 | ||

| 51 and above | 1 | 1 | 2 | ||

| Total | 45 | 38 | 83 | ||

| Total | Age Range | 20 and below | 19 | 32 | 51 |

| 21–30 | 61 | 31 | 92 | ||

| 31–40 | 71 | 57 | 128 | ||

| 41–50 | 73 | 22 | 95 | ||

| 51 and above | 2 | 5 | 7 | ||

| Total | 226 | 147 | 373 | ||

| Construct | Items | Measure | Supporting References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Performance Expectancy | PE1 | I can buy groceries more rapidly when I use online grocery apps. | [17,32] |

| PE2 | Using online grocery apps improves my chances of accomplishing more essential goals. | ||

| PE3 | I can save much time using online grocery apps. | ||

| PE4 | Online grocery shopping is convenient because it reduces my reliance on store hours. | ||

| Effort Expectancy | EE1 | Online grocery services are simple to use, in my opinion. | [17] |

| EE2 | I have no trouble finding what I need when using online groceries. | ||

| EE3 | It is not difficult to order things from an online grocery app. | ||

| EE4 | Using an online grocery store, I can quickly check the availability of goods. | ||

| Social Influence | SI1 | My family members believe that ordering groceries online is a great idea. | [17,57] |

| SI2 | Most of my acquaintances and friends think that buying groceries online is an excellent idea. | ||

| SI3 | In my community, shopping for groceries online is a status symbol. | ||

| SI4 | People who sway my decisions believe that I should shop for groceries online. | ||

| SI5 | People around me think it is perfectly acceptable to shop for groceries online. | ||

| Facilitating Conditions | FC1 | I have the necessary resources to shop on an online grocery store. | [17,57,58] |

| FC2 | I have the essential skills to shop for groceries online. | ||

| FC3 | When I have problems using an online grocery app, a specialized person (or group) is accessible to help me. | ||

| FC4 | Other technologies I use are compatible with online grocery shopping. | ||

| Hedonic Motivation | HM1 | I find online grocery apps fun to use. | [10,57,58] |

| HM2 | I find online grocery apps enjoyable to use. | ||

| HM3 | I find online grocery apps very entertaining. | ||

| HM4 | The use of online grocery apps amuses me. | ||

| HM5 | The use of online grocery apps makes me feel good. | ||

| HM6 | I feel comfortable using online grocery apps. | ||

| Cues to Action | CA1 | My family and friends will support me if I shop for groceries online. | [21,53] |

| CA2 | Because the government strongly encourages me not to go out, I shop for groceries online. | ||

| CA3 | I will only buy groceries on-site after COVID-19 if I am given appropriate external information about existing safeguards; as a result, I prefer to shop online. | ||

| CA4 | More people are using online grocery apps during the pandemic; thus, I use online grocery apps. | ||

| CA5 | My own experience with online grocery apps has convinced me to use them again. | ||

| Perceived Benefits | PBN1 | Using online grocery apps reduces my chance of infection; thus, I use online grocery apps. | [54,55] |

| PBN2 | Using online grocery apps decreases the severity and the chance of complications if I get infected with COVID-19; thus, I use online grocery apps. | ||

| PBN3 | Using online grocery apps helps me to avoid contact with other people and crowded places; thus, I use online grocery apps. | ||

| PBN4 | I want to adhere to the principles of prevention and government restrictions; thus, I use online grocery apps. | ||

| PBN5 | I stay at home to control the pandemic sooner; thus, I use online grocery apps. | ||

| Perceived Barriers | PBR1 | It is difficult to follow the COVID-19 prevention recommendations; thus, I use online grocery apps. | [21] |

| PBR2 | I do not have the patience to follow COVID-19 precautionary measures; thus, I use online grocery apps. | ||

| PBR3 | I find it challenging to repeatedly wash my hands with soap and water; thus, I use online grocery apps. | ||

| PBR4 | It is tough to avoid touching your hands, lips, nose, or eyes; thus, I use online grocery apps. | ||

| PBR5 | A face shield is inconvenient to use and uncomfortable; thus, I use online grocery apps. | ||

| PBR6 | I find disinfectant solutions expensive and scarce in the market; thus, I use online grocery apps. | ||

| Perceived Severity | PSV1 | COVID-19 has a high mortality rate; thus, I use online grocery apps. | [21,58] |

| PSV2 | COVID-19 is very dangerous; thus, I use online grocery apps. | ||

| PSV3 | The transmission of COVID-19 is relatively high; thus, I use online grocery apps. | ||

| PSV4 | If I am infected with COVID-19, and I believe my health will be seriously harmed; thus, I use online grocery apps. | ||

| PSV5 | Because of the possibility of contracting COVID-19, I will not go to the hospital if I become unwell with another condition; thus, I use online grocery apps. | ||

| Perceived Susceptibility | PSC1 | I believe I am at risk of COVID-19; thus, I use online grocery apps. | [21,58,63] |

| PSC2 | I believe I have a higher chance of contacting COVID-19 than before; thus, I use online grocery apps. | ||

| PSC3 | I worry about COVID-19, and I cannot carry out my daily activities such as before; thus, I use online grocery apps. | ||

| PSC4 | I might contract COVID-19 if I do not take any preventive measures; thus, I use online grocery apps. | ||

| PSC5 | I am terrified to contact sick people with the flu (e.g., cough, sneezing, runny nose, or fever); thus, I use online grocery apps. | ||

| Behavioral Intentions | BI1 | I intend to use online grocery apps to prevent infection from COVID-19. | [11,63] |

| BI2 | I intend to use online grocery apps to protect my family from COVID-19 infection. | ||

| BI3 | I intend to use online grocery apps if they become widely available in my area. | ||

| BI4 | I intend to recommend online grocery apps to my family and friends for safety during the COVID-19 pandemic. | ||

| Usage Behavior | UB1 | I have used online grocery apps. | [32] |

| UB2 | I have used different types of online grocery apps. | ||

| UB3 | I frequently use online grocery apps in buying goods. | ||

| UB4 | I frequently search for new items or goods on an online grocery app. |

| Construct | Items | Mean | SD. | FL (≥0.7) | α (≥0.7) | CR (≥0.7) | AVE (≥0.5) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Performance Expectancy | PE1 | 3.62 | 1.16824 | 0.86 | 0.866 | 0.908 | 0.713 |

| PE2 | 3.63 | 1.16937 | 0.83 | ||||

| PE3 | 4.03 | 1.07465 | 0.83 | ||||

| PE4 | 3.91 | 1.10626 | 0.85 | ||||

| Effort Expectancy | EE1 | 3.78 | 1.07440 | 0.84 | 0.866 | 0.906 | 0.707 |

| EE2 | 3.50 | 1.17689 | 0.79 | ||||

| EE3 | 3.62 | 1.09733 | 0.89 | ||||

| EE4 | 3.69 | 1.13493 | 0.84 | ||||

| Social Influence | SI1 | 3.45 | 1.21398 | 0.89 | 0.899 | 0.929 | 0.766 |

| SI2 | 3.41 | 1.15751 | 0.90 | ||||

| SI3 | 3.94 | 1.23617 | - | ||||

| SI4 | 3.09 | 1.17690 | 0.82 | ||||

| SI5 | 3.38 | 1.09674 | 0.87 | ||||

| Facilitating Condition | FC1 | 4.03 | 1.00609 | 0.84 | 0.818 | 0.881 | 0.650 |

| FC2 | 4.15 | 0.93842 | 0.86 | ||||

| FC3 | 3.47 | 1.12510 | 0.71 | ||||

| FC4 | 4.14 | 0.90320 | 0.81 | ||||

| Hedonic Motivation | HM1 | 3.65 | 1.09898 | 0.91 | 0.953 | 0.962 | 0.811 |

| HM2 | 3.62 | 1.10738 | 0.93 | ||||

| HM3 | 3.58 | 1.12512 | 0.92 | ||||

| HM4 | 3.59 | 1.11733 | 0.91 | ||||

| HM5 | 3.50 | 1.08664 | 0.90 | ||||

| HM6 | 3.62 | 1.12185 | 0.82 | ||||

| Cues to Action | CA1 | 4.00 | 1.05875 | 0.86 | 0.906 | 0.930 | 0.726 |

| CA2 | 3.93 | 1.07787 | 0.87 | ||||

| CA3 | 3.87 | 1.10937 | 0.84 | ||||

| CA4 | 3.81 | 1.12506 | 0.86 | ||||

| CA5 | 3.77 | 1.12054 | 0.84 | ||||

| Perceived Benefits | PBN1 | 4.14 | 1.02677 | 0.92 | 0.950 | 0.961 | 0.833 |

| PBN2 | 4.04 | 1.09789 | 0.88 | ||||

| PBN3 | 4.18 | 1.04419 | 0.93 | ||||

| PBN4 | 4.01 | 1.04075 | 0.91 | ||||

| PBN5 | 4.13 | 1.04704 | 0.92 | ||||

| Perceived Barriers | PBR1 | 3.11 | 1.34974 | 0.80 | 0.939 | 0.948 | 0.696 |

| PBR2 | 3.02 | 1.30325 | 0.83 | ||||

| PBR3 | 3.40 | 1.31112 | 0.81 | ||||

| PBR4 | 3.97 | 1.38101 | 0.87 | ||||

| PBR5 | 3.43 | 1.39447 | 0.82 | ||||

| PBR6 | 3.00 | 1.33903 | 0.87 | ||||

| Perceived Severity | PSV1 | 3.97 | 1.02879 | 0.93 | 0.918 | 0.940 | 0.763 |

| PSV2 | 4.04 | 1.03086 | 0.95 | ||||

| PSV3 | 4.09 | 1.01562 | 0.94 | ||||

| PSV4 | 4.02 | 1.07000 | 0.91 | ||||

| PSV5 | 3.54 | 1.19195 | 0.78 | ||||

| Perceived Susceptibility | PSC1 | 3.88 | 1.12352 | 0.83 | 0.925 | 0.943 | 0.769 |

| PSC2 | 3.80 | 1.12561 | 0.86 | ||||

| PSC3 | 3.85 | 1.07962 | 0.93 | ||||

| PSC4 | 3.88 | 1.08302 | 0.90 | ||||

| PSC5 | 4.06 | 1.00630 | 0.87 | ||||

| Behavioral Intentions | BI1 | 4.16 | 1.01465 | 0.88 | 0.887 | 0.922 | 0.747 |

| BI2 | 4.08 | 1.02074 | 0.87 | ||||

| BI3 | 3.92 | 1.04199 | 0.81 | ||||

| BI4 | 4.11 | 1.02718 | 0.89 | ||||

| Usage Behavior | UB1 | 4.08 | 1.19800 | 0.81 | 0.847 | 0.896 | 0.683 |

| UB2 | 3.81 | 1.28629 | 0.79 | ||||

| UB3 | 3.65 | 1.24573 | 0.83 | ||||

| UB4 | 3.89 | 1.20451 | 0.88 |

| No | Relationship | Beta Coefficient | p-Value | Result | Significance | Hypothesis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | PE→BI | 0.168 | 0.002 | Positive | Significant | Accepted |

| 2 | EE→BI | −0.095 | 0.142 | Negative | Not significant | Rejected |

| 3 | SI→BI | 0.012 | 0.875 | Positive | Not significant | Rejected |

| 4 | HM→BI | 0.090 | 0.227 | Positive | Not significant | Rejected |

| 5 | FC→BI | −0.007 | 0.916 | Negative | Not significant | Rejected |

| 6 | PBN→BI | 0.239 | 0.006 | Positive | Significant | Accepted |

| 7 | PBR→BI | −0.136 | 0.006 | Negative | Significant | Rejected |

| 8 | PSV→BI | 0.210 | 0.012 | Positive | Significant | Accepted |

| 9 | PSC→BI | 0.036 | 0.704 | Positive | Not significant | Rejected |

| 10 | CA→BI | 0.166 | 0.028 | Positive | Significant | Accepted |

| 11 | CA→UB | 0.227 | 0.000 | Positive | Significant | Accepted |

| 12 | BI→UB | 0.454 | 0.000 | Positive | Significant | Accepted |

| Construct | BI | CA | EE | FC | HM | PBN | PBR | PE | PSC | PSV | SI | UB |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BI | 0.864 | |||||||||||

| CA | 0.536 | 0.852 | ||||||||||

| EE | 0.378 | 0.575 | 0.841 | |||||||||

| FC | 0.336 | 0.444 | 0.575 | 0.806 | ||||||||

| HM | 0.444 | 0.599 | 0.670 | 0.594 | 0.900 | |||||||

| PBN | 0.569 | 0.714 | 0.530 | 0.402 | 0.571 | 0.912 | ||||||

| PBR | 0.232 | 0.529 | 0.372 | 0.136 | 0.379 | 0.458 | 0.834 | |||||

| PE | 0.478 | 0.575 | 0.740 | 0.579 | 0.676 | 0.567 | 0.334 | 0.844 | ||||

| PSC | 0.513 | 0.719 | 0.478 | 0.371 | 0.521 | 0.720 | 0.526 | 0.574 | 0.877 | |||

| PSV | 0.537 | 0.716 | 0.636 | 0.418 | 0.550 | 0.770 | 0.545 | 0.585 | 0.806 | 0.873 | ||

| SI | 0.387 | 0.621 | 0.660 | 0.502 | 0.639 | 0.494 | 0.495 | 0.678 | 0.542 | 0.550 | 0.831 | |

| UB | 0.576 | 0.470 | 0.370 | 0.307 | 0.401 | 0.390 | 0.251 | 0.393 | 0.403 | 0.402 | 0.416 | 0.827 |

| Construct | BI | CA | EE | FC | HM | PBN | PBR | PE | PSC | PSV | SI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CA | 0.585 | ||||||||||

| EE | 0.402 | 0.638 | |||||||||

| FC | 0.395 | 0.513 | 0.659 | ||||||||

| HM | 0.479 | 0.637 | 0.715 | 0.671 | |||||||

| PBN | 0.612 | 0.878 | 0.568 | 0.454 | 0.597 | ||||||

| PBR | 0.229 | 0.562 | 0.402 | 0.150 | 0.382 | 0.462 | |||||

| PE | 0.536 | 0.647 | 0.827 | 0.688 | 0.744 | 0.624 | 0.352 | ||||

| PSC | 0.553 | 0.784 | 0.513 | 0.423 | 0.546 | 0.760 | 0.547 | 0.636 | |||

| PSV | 0.569 | 0.784 | 0.583 | 0.470 | 0.582 | 0.816 | 0.608 | 0.650 | 0.652 | ||

| SI | 0.418 | 0.683 | 0.731 | 0.573 | 0.689 | 0.529 | 0.549 | 0.765 | 0.590 | 0.609 | |

| UB | 0.642 | 0.524 | 0.401 | 0.369 | 0.432 | 0.423 | 0.265 | 0.451 | 0.443 | 0.438 | 0.474 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gumasing, M.J.J.; Prasetyo, Y.T.; Persada, S.F.; Ong, A.K.S.; Young, M.N.; Nadlifatin, R.; Redi, A.A.N.P. Using Online Grocery Applications during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Their Relationship with Open Innovation. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2022, 8, 93. https://doi.org/10.3390/joitmc8020093

Gumasing MJJ, Prasetyo YT, Persada SF, Ong AKS, Young MN, Nadlifatin R, Redi AANP. Using Online Grocery Applications during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Their Relationship with Open Innovation. Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity. 2022; 8(2):93. https://doi.org/10.3390/joitmc8020093

Chicago/Turabian StyleGumasing, Ma. Janice J., Yogi Tri Prasetyo, Satria Fadil Persada, Ardvin Kester S. Ong, Michael Nayat Young, Reny Nadlifatin, and Anak Agung Ngurah Perwira Redi. 2022. "Using Online Grocery Applications during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Their Relationship with Open Innovation" Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity 8, no. 2: 93. https://doi.org/10.3390/joitmc8020093

APA StyleGumasing, M. J. J., Prasetyo, Y. T., Persada, S. F., Ong, A. K. S., Young, M. N., Nadlifatin, R., & Redi, A. A. N. P. (2022). Using Online Grocery Applications during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Their Relationship with Open Innovation. Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity, 8(2), 93. https://doi.org/10.3390/joitmc8020093