How to Respond to Disruptive Innovation in Online Retail Platforms

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- “What aspects of disruptive innovation and the platform economy made the disruptor so powerful while turning the core competencies of incumbents into core rigidities?”

- “What were the actions that incumbent firms took to respond to disruptive innovation?”

2. Literature Review and Research Framework

2.1. Disruptive Innovation

2.2. Incumbent’s Response to Disruptive Innovation

2.3. Platform Business

3. Method

4. The Background of SSG

5. The Korean Retail Industry

5.1. Online–Offline Gap in Business Model

5.2. The Changing History of Online Retail

5.2.1. Disruptive Innovation in Korean Retail Industry

5.2.2. Online Retailers Becoming Disruptors: Competitor Analysis

The First-Generation Online Marketplace: Gmarket, Auction, 11th Street

The First-Generation Social Commerce: Coupang, WeMakePrice, TMON

6. SSG’s Response to Disruptive Innovation

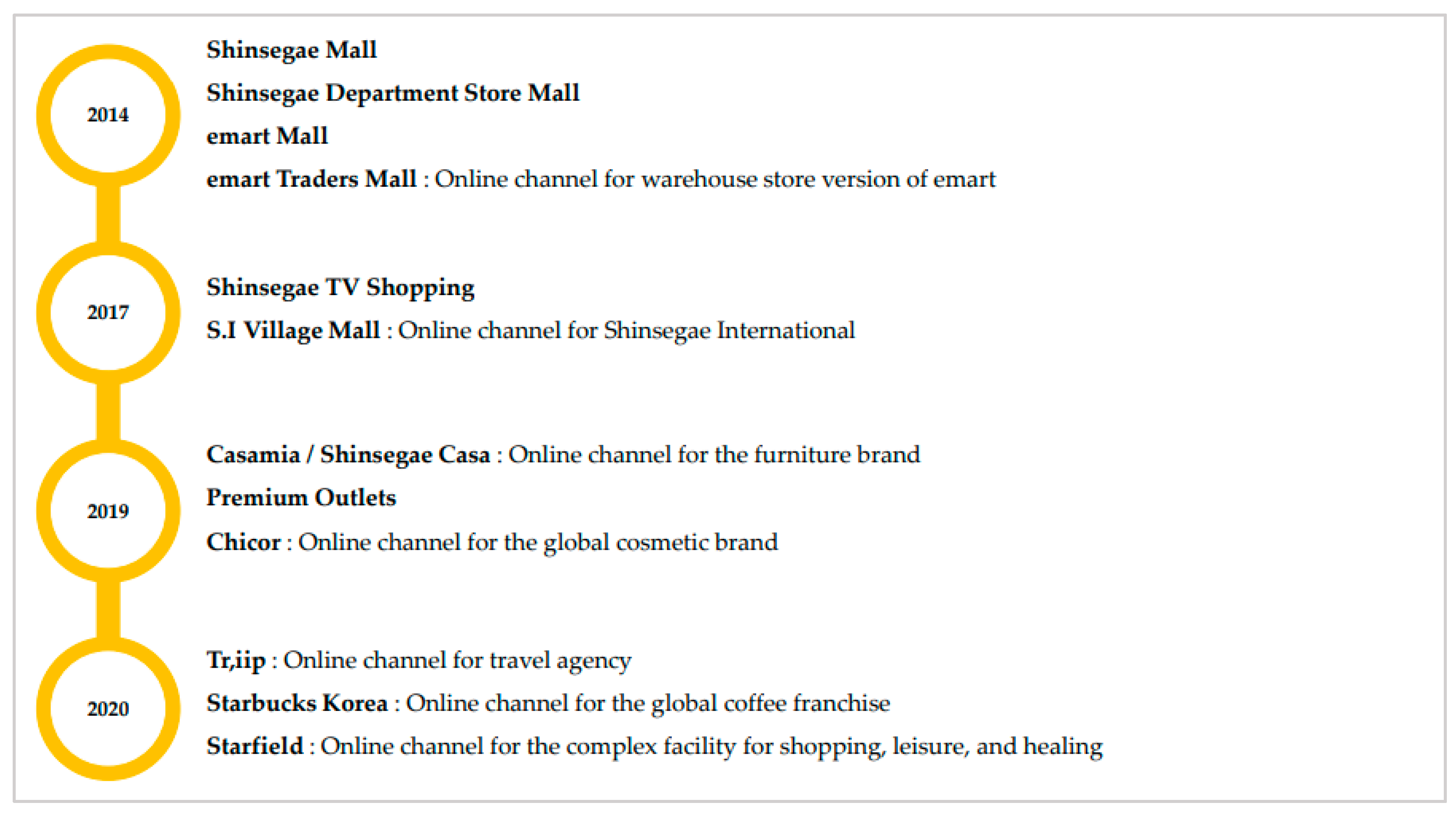

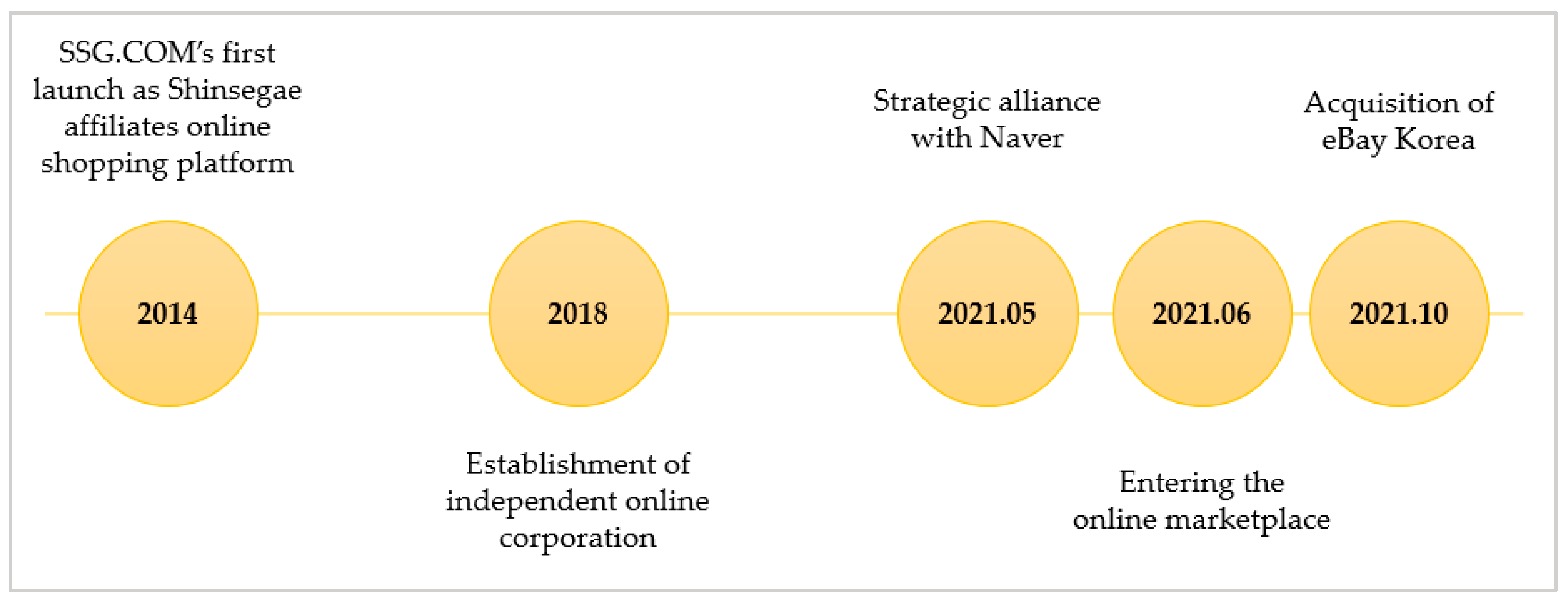

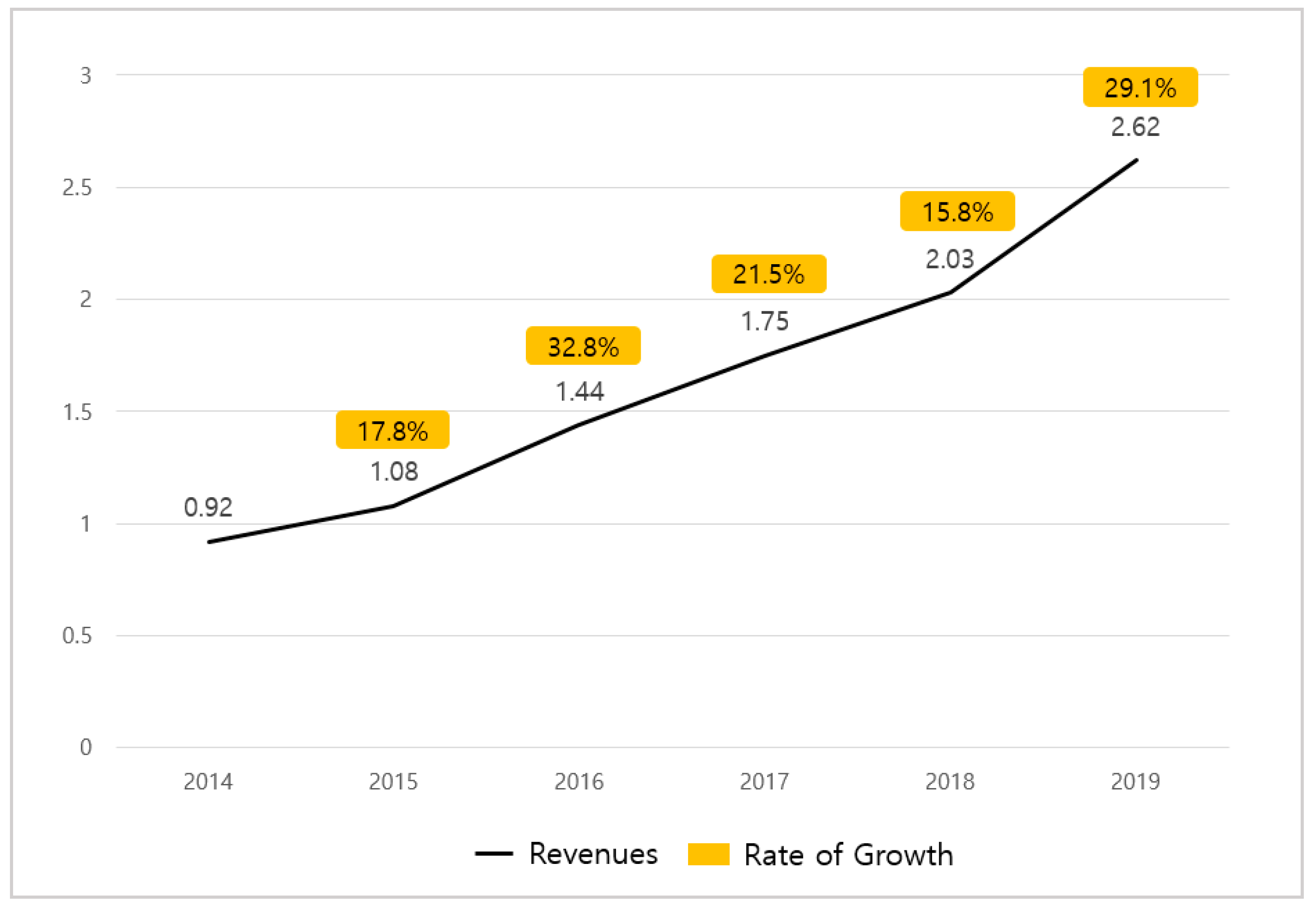

6.1. SSG’s Internal Attempt to Penetrate the Online Marketplace

6.2. Core Competency Turning into Core Rigidity

6.3. External Development: Strategic Alliance with Naver and Acquisition of eBay

7. Discussion: Disruptive Innovation, Platform Business in the Retail Industry, and Open Innovation Dynamics

8. Conclusions

8.1. Implications: The Theoretical and Practical Value of This Research

8.2. Limitations and Future Research Agenda

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix B

Appendix C

Appendix D

References

- Bakos, J.Y. Reducing buyer search costs: Implications for electronic marketplaces. Manag. Sci. 1997, 43, 1676–1692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Harrington, J.E., Jr.; Leahey, M.F. Equilibrium pricing in a (partial) search market: The shopbot paradox. Econ. Lett. 2007, 94, 111–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Li, H.; Simchi-Levi, D.; Wu, M.X.; Zhu, W. Price Competition and Assortment Display in Online Marketplace. 2021. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3913764 (accessed on 17 June 2021).

- Ministry of Industry, Trade and Energy. Available online: https://www.motie.go.kr/motie/ne/presse/press2/bbs/bbsView.do?bbs_cd_n=81&bbs_seq_n=163757 (accessed on 16 June 2021).

- Business Watch. Available online: http://news.bizwatch.co.kr/article/consumer/2020/02/13/0017/facebook (accessed on 17 June 2021).

- Homeplus, Operating Profit of 93.3 Billion Won in Fiscal 2020… 41.8%↓from the Previous Year. Available online: https://n.news.naver.com/article/003/0010534666 (accessed on 17 June 2021).

- Shinsegae Group Launches Online Integrated Corporation… “Achieve 10 Trillion Won in Sales by 2023”. News1. Available online: https://m.news1.kr/articles/?3556871 (accessed on 30 July 2021).

- There Is No OOO in the SSG.com Open Market… Earning Trust. New Daily Economy. Available online: https://biz.newdaily.co.kr/site/data/html/2021/03/25/2021032500069.html (accessed on 9 January 2022).

- ‘Anti-Coupang Solidarity’ E-Mart-Naver Acquires eBay Korea… Will They Become ‘No. 1’ E-Commerce? Dong-A Ilbo. Available online: https://www.donga.com/news/Economy/article/all/20210616/107469170/1 (accessed on 9 January 2022).

- Govindarajan, V.; Kopalle, P.K. Disruptiveness of innovations: Measurement and an assessment of reliability and validity. Strateg. Manag. J. 2006, 27, 189–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, D.S. The antitrust economics of multi-sided platforms markets. Yale J. Regul. 2003, 20, 325–382. [Google Scholar]

- Christensen, C.; Raynor, M.E.; McDonald, R. Disruptive Innovation; Harvard Business Review: Brighton, MA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Christensen, C.M. The Innovator’s Dilemma: When New Technologies Cause Great Firms to Fail; Harvard Business Press: Boston, MA, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Reinhardt, R.; Gurtner, S. Differences between early adopters of disruptive and sustaining innovations. J. Bus. Res. 2015, 68, 137–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolpert, J.D. Breaking out of the innovation box. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2002, 80, 76–83, 148. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hannan, M.T.; Freeman, J. Structural inertia and organizational change. Am. Sociol. Rev. 1984, 49, 149–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, D.; Amburgey, T.L. Organizational inertia and momentum: A dynamic model of strategic change. Acad. Manag. J. 1991, 34, 591–612. [Google Scholar]

- Christensen, C.M.; McDonald, R.; Altman, E.J.; Palmer, J.E. Disruptive innovation: An intellectual history and directions for future research. J. Manag. Stud. 2018, 55, 1043–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gans, J. The other disruption. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2016, 2016, 2–8. [Google Scholar]

- Henderson, R. The innovator’s dilemma as a problem of organizational competence. J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 2005, 23, 5–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonard-Barton, D. Core capabilities and core rigidities: A paradox in managing new product development. Strat. Manag. J. 1992, 13, 111–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrew, A.K.; Baatartogtokh, B. How useful is the theory of disruptive innovation? MIT Sloan Manag. Rev. 2015, 57, 77–90. [Google Scholar]

- Markides, C. Disruptive innovation: In need of better theory. J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 2005, 23, 19–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, C.M.; Johnson, M.W. What are Business Models, and how are They Built? Harv. Bus. Sch. Note 2009, 9–610. Available online: https://www.hbs.edu/faculty/Pages/item.aspx?num=37729 (accessed on 17 May 2022).

- Wallin, A.; Pihlajamaa, M.; Malmelin, N. How do large corporations manage disruption? The perspective of manufacturing executives in Finland. Eur. J. Innov. Manag. 2021, 25, 19–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilkki, K.; Mäntylä, M.; Karhu, K.; Hämmäinen, H.; Ailisto, H. A disruption framework. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2018, 129, 275–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghura, A.S.; Erkut, B. Corporate entrepreneurship programmes as mechanisms to accelerate product innovations. Entrep. Res. J. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tushman, M.L.; O’Reilly, C.A., III. Ambidextrous organizations: Managing evolutionary and revolutionary change. Calif. Manag. Rev. 1996, 38, 8–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nizar, M.B. Innovator’s dilemma: Review of the main responses to disruptive innovation. J. Intercult. Manag. 2019, 11, 105–124. [Google Scholar]

- O’Reilly, C.A., III; Tushman, M.L. Ambidexterity as a dynamic capability: Resolving the innovator’s dilemma. Res. Organ. Behav. 2008, 28, 185–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marx, M.; Gans, J.S.; Hsu, D.H. Dynamic commercialization strategies for disruptive technologies: Evidence from the speech recognition industry. Manag. Sci. 2013, 60, 3103–3123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gawer, A. Bridging differing perspectives on technological platforms: Toward an integrative framework. Res. Policy 2014, 43, 1239–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Boudreau, K.J.; Jeppesen, L.B. Unpaid crowd complementors: The platform network effect mirage. Strat. Manag. J. 2014, 36, 1761–1777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Evans, D.S.; Hagiu, A.; Schmalensee, R. Invisible Engines: How Software Platforms Drive Innovation and Transform Industries. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2747032 (accessed on 13 March 2016).

- Cennamo, C.; Santalo, S. Platform competition: Strategic trade-offs in platform markets. Strateg. Manag. J. 2013, 34, 1331–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McIntyre, D.P.; Srinivasan, A. Networks, platforms, and strategy: Emerging views and next steps. Strat. Manag. J. 2016, 38, 141–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A. E-commerce: Role of E-commerce in today’s business. Int. J. Comput. Corp. Res. 2014, 4, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, R.K. Case Study Research: Design and Methods, 3rd ed.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenhardt, K.M. Building theories from case study research. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1989, 14, 532–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baxter, P.; Jack, S. Qualitative case study methodology: Study design and implementation for novice researchers. Qual. Rep. 2008, 13, 544–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zainal, Z. Case study as a research method. J. Kemanus. Bil 2007, 9, 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Wikipedia. Available online: https://ko.wikipedia.org/wiki/%EC%9D%B4%EB%B3%91%EC%B2%A0 (accessed on 14 December 2021).

- Shinsegae Group Newsroom. Available online: https://www.shinsegaegroupnewsroom.com/ssggroup/# (accessed on 14 December 2021).

- YouTube. Available online: https://youtu.be/Zz1bF7QWMxI (accessed on 14 December 2021).

- YouTube (Shinsegae Group Newsroom). Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ELwwJp48FgE (accessed on 17 May 2022).

- Johnson, M.W.; Christensen, C.M.; Kagermann, H. Reinventing your business model. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2008, 86, 57–68. [Google Scholar]

- Katz, M.L.; Shapiro, C. Technology adoption in the presence of network externalities. J. Polit. Econ. 1986, 94, 822–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maxwell, C.; Kominers, S.D. What Makes an Online Marketplace Disruptive? Harvard Business Review Digital Articles. 2021. Available online: https://hbr.org/2021/05/what-makes-an-online-marketplace-disruptive (accessed on 10 January 2022).

- Statistics Korea. Available online: https://kostat.go.kr/portal/korea/kor_nw/1/12/3/index.board?bmode=list&bSeq=&aSeq=&pageNo=1&rowNum=10&navCount=10&currPg=&searchInfo=&sTarget=title&sTxt= (accessed on 28 September 2021).

- Hankyoreh. Available online: https://www.hani.co.kr/arti/economy/economy_general/350190.html (accessed on 28 September 2021).

- ‘Sold out’ eBay Korea, Stagnant Earnings. Paxnet News. Available online: https://paxnetnews.com/articles/57910 (accessed on 28 September 2021).

- Social Commerce. Wikipedia. Available online: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Social_commerce (accessed on 13 August 2021).

- Koo, J.K. Social Commerce Market Status and Challenges. Ind. Econ. Rev. 2015, 49, 34–42. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, H.H.; Lee, B.H.; Baek, P.H. Changes in the domestic social commerce market and the corporate evolution—Focusing on coupang, TMON and WeMakePrice. Rev. Bus. Hist. 2017, 84, 135–154. [Google Scholar]

- The 10th Anniversary of the E-Commerce Big 3, Coupang’s Secret to Seizing the Throne. Maeil Business Newspaper. Available online: https://www.mk.co.kr/news/home/view/2020/11/1230592/ (accessed on 13 August 2021).

- The Value News. Available online: http://www.thevaluenews.co.kr/news/view.php?idx=164298 (accessed on 20 August 2021).

- Financial Economic TV. Available online: https://www.fetv.co.kr/news/article.html?no=92178 (accessed on 20 August 2021).

- The Joongang. Available online: https://www.joongang.co.kr/article/20362392#home (accessed on 27 August 2021).

- Coupang, Last Year’s Sales Reached 14 Trillion Won… Reduce Losses and Increase Labor Costs. Money Today. Available online: https://news.mt.co.kr/mtview.php?no=2021041320101654769 (accessed on 28 September 2021).

- Newspim. Available online: https://www.newspim.com/news/view/20210419001017 (accessed on 31 August 2021).

- Maeil Business Newspaper. Available online: https://m.mk.co.kr/news/it/view-amp/2021/05/463524/ (accessed on 6 October 2021).

- Money Today. Available online: https://m.mt.co.kr/renew/view_amp.html?no=2016080217075226350 (accessed on 6 October 2021).

- Naver Closes Open Market ‘Shop N’ and Introduces ‘Store Farm’ (Sangbo). News1. Available online: https://www.news1.kr/articles/?1659315 (accessed on 6 October 2021).

- Unusual Naver… The Timing of the Shopping Spin-Off Is Imminent. Asia Business Daily. Available online: https://cm.asiae.co.kr/ampview.htm?no=2020090708160602696 (accessed on 6 October 2021).

- [Brand Reputation] February 2021 Big Data Analysis of Duty Free Brands… 1st Shinsegae Duty Free, 2nd Hyundai Department Store Duty Free, 3rd Lotte Duty Free. Korea Institute of Business Reputation. Available online: https://brikorea.com/bbs/board.php?bo_table=rep_1&wr_id=191&sst=wr_datetime&sod=desc&sop=and&page=58 (accessed on 15 June 2021).

- [Brand Reputation] Big Data Analysis of Wholesale Brands in February 2021… 1st Emart, 2nd Costco, 3rd Homeplus. Korea Institute of Business Reputation. Available online: https://brikorea.com/bbs/board.php?bo_table=rep_1&wr_id=193&page=61 (accessed on 15 June 2021).

- [Brand Reputation] Big Data Analysis Results for Department Store Brands in February 2021… 1st Lotte Department Store, 2nd Hyundai Department Store, 3rd Shinsegae Department Store. Korea Institute of Business Reputation. Available online: https://brikorea.com/bbs/board.php?bo_table=rep_1&wr_id=192&sst=wr_datetime&sod=desc&sop=and&page=55 (accessed on 15 June 2021).

- The Reason Why Strawberries Ordered Online Can Be Delivered in 3 Hours. YouTube (EO). Available online: https://youtu.be/1C1Wpktw9q8 (accessed on 16 June 2021).

- Eisenmann, T.; Parker, G.; Van Alstyne, M. Strategies for two-sided markets. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2006, 84, 92–101. [Google Scholar]

- DART(SSG.COM). Available online: http://dart.fss.or.kr/dsaf001/main.do?rcpNo=20210324000289 (accessed on 17 June 2021).

- Open Market A to Z. SSG Partners. Available online: https://partners.ssgadm.com/contents/detail.ssg?ssgptCtntId=00000051 (accessed on 19 June 2021).

- Wemakeprice “Now the Rival Is ‘Naver’”… Challenge to ‘AI Shopping’. Money, S. Available online: https://moneys.mt.co.kr/news/mwView.php?no=2021122214418058911 (accessed on 8 January 2022).

- SSG.com to Solidify the Three Powers in E-Commerce… Aiming for a Walmart-Style Open Market. ChosunBiz. Available online: https://biz.chosun.com/site/data/html_dir/2021/02/18/2021021802921.html (accessed on 8 January 2022).

- Half-Open SSG.com vs. 0% Commission Lotte on, Distribution Dinosaur Open Market War. ChosunBiz. Available online: https://biz.chosun.com/distribution/channel/2021/05/10/AQRR2YJ6V5G47FBDWPUXNBTLB4/ (accessed on 8 January 2022).

- Kim, J. The platform business model and business ecosystem: Quality management and revenue structures. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2016, 24, 2113–2132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DART (Emart). Available online: https://dart.fss.or.kr/dsaf001/main.do?rcpNo=20210531001049 (accessed on 19 April 2022).

- SSG.com Listing ‘Getting out of E-Mart’ Is the Key. Top Daily. Available online: https://www.topdaily.kr/articles/78850 (accessed on 17 April 2022).

- Shinsegae Group Opens ‘Unprecedented’ Commerce with Naver. Shinesegae Group NewsRoom. Available online: https://www.shinsegaegroupnewsroom.com/59178/ (accessed on 15 June 2021).

- ‘Naver-Shinsegae Group Alliance’ against Coupang…Future Strategy. Yonhap News. Available online: https://www.yna.co.kr/view/AKR20210316083000030 (accessed on 2 August 2021).

- Yongjin Jung, Who Works Hard on E-Commerce, How to Cooperate with Naver? AsiaToday. Available online: https://m.news.nate.com/view/20210408n04625?mid=m02 (accessed on 2 August 2021).

- Growing a Specialty Store on SSG.com Naver… The Reason E-Mart Joined Hands with Competitors. Sisajournal, E. Available online: http://www.sisajournal-e.com/news/articleView.html?idxno=226915 (accessed on 3 August 2021).

- Naver-Shinsegae-CJ ‘Anti-Coupang Alliance’ Appeared. Maeil Business Newspaper. Available online: https://www.mk.co.kr/news/business/view/2021/03/251212/ (accessed on 2 August 2021).

- E-Mart Acquires eBay Korea for 3.4 Trillion Won… Overtakes Coupang and Becomes the 2nd Largest E-Commerce Company. Chosun Biz. Available online: https://biz.chosun.com/distribution/channel/2021/06/24/FHRCXSZ3W5D2HGOQ65GNYK33CQ/ (accessed on 6 August 2021).

- Kang Hee-Seok, CEO of E-Mart, “With the Acquisition of eBay, We Will Become an Absolute Powerhouse in Distribution… I Will Surpass Coupang” [Professional]. Newspim. Available online: https://www.newspim.com/news/view/20210624001256 (accessed on 17 May 2022).

- Shinsegae Group to Seize SSG.com Listing Opportunity in Ebay Acquisition. Maeil News Agency. Available online: https://www.m-i.kr/news/articleView.html?idxno=837529 (accessed on 8 August 2021).

- Shinsegae E-Mart Acquires eBay Korea for 3.4 Trillion Won, 2nd Place in E-Commerce (Overall). Yonhap News. Available online: https://www.yna.co.kr/view/AKR20210624140200030 (accessed on 8 August 2021).

- Chesbrough, H.; Vanhaverbeke, W.; West, J. (Eds.) Open Innovation: Researching a New Paradigm; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Chesbrough, H.W. The era of open innovation. MIT Sloan Manag. Rev. 2003, 44, 35–41. [Google Scholar]

- Yun, J.J. Open innovation: Technology, market and complexity in South Korea. Sci. Technol. Soc. 2016, 21, 319–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chesbrough, H.W. Open Innovation: The New Imperative for Creating and Profiting from Technology; Harvard Business Press: Brighton, MA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Christensen, C.M. The ongoing process of building a theory of disruption. J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 2005, 23, 39–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stepen, K.K.; Min, S. Business model innovation performance: When does adding a new business model benefit an incumbent? Strateg. Entrep. J. 2015, 9, 34–57. [Google Scholar]

- Constantinos, C.M.; Oyon, D. What to do against disruptive business models (when and how to play two games at once). MIT Sloan Manag. Rev. 2010, 51, 25–32. [Google Scholar]

- Schiavi, G.S.; Behr, A. Emerging technologies and new business models: A review on disruptive business models. Innov. Manag. Rev. 2018, 15, 338–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Christensen, C.M.; Raynor, M.; McDonald, R. What is disruptive innovation? Harv. Bus. Rev. 2015, 93, 44–53. [Google Scholar]

- Pereira, S.A.; Imbrizi, F.G.; Freitas, A.D.G.; Alvarenga, M.A. Business model as an inducer of disruptive innovations: The case of gol airlines. Int. J. Innov. 2015, 3, 28–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stettner, U.; Lavie, D. Ambidexterity under scrutiny: Exploration and exploitation via internal organization, alliances, and acquisitions. Strat. Manag. J. 2013, 35, 1903–1929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ondrejka, C. Escaping the gilded cage: User created content and building the metaverse. NYL Sch. L. Rev. 2004, 49, 81. [Google Scholar]

- Jung Yong-Jin’s E-Mart, Jung Yu-Kyeong’s Shinsegae Department Store… A ‘Watching Point’ Separation of Affiliates for Gift Tax. Chosun Biz. Available online: https://biz.chosun.com/distribution/channel/2021/07/23/RIPRXP6GONGKFFCEOSUDGWBGNY/ (accessed on 12 May 2022).

- SSG.COM Newsroom. Available online: http://company.ssg.com/channel/news.ssg?page=16&pageSize=20 (accessed on 11 May 2022).

- SSG.com Opens Starbucks Online Shop. Shinsegae Group Newsroom. Available online: https://www.shinsegaegroupnewsroom.com/49173/ (accessed on 11 May 2022).

- SSG.com Opens ‘Starfield Online Store’. Shinsegae Group Newsroom. Available online: https://www.shinsegaegroupnewsroom.com/48631/ (accessed on 11 May 2022).

- SSG.COM. Available online: http://company.ssg.com/intrd/keybsns.ssg (accessed on 15 June 2021).

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yang, S.; Kim, Y.; Choi, S. How to Respond to Disruptive Innovation in Online Retail Platforms. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2022, 8, 130. https://doi.org/10.3390/joitmc8030130

Yang S, Kim Y, Choi S. How to Respond to Disruptive Innovation in Online Retail Platforms. Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity. 2022; 8(3):130. https://doi.org/10.3390/joitmc8030130

Chicago/Turabian StyleYang, Seojeong, Yoonji Kim, and Seungho Choi. 2022. "How to Respond to Disruptive Innovation in Online Retail Platforms" Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity 8, no. 3: 130. https://doi.org/10.3390/joitmc8030130

APA StyleYang, S., Kim, Y., & Choi, S. (2022). How to Respond to Disruptive Innovation in Online Retail Platforms. Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity, 8(3), 130. https://doi.org/10.3390/joitmc8030130