Open Innovation for Sustainability in the Social Enterprises: An Empirical Evidence

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- Q1. What innovation for sustainability practices do social enterprises implement?

- Q2. How does the mechanism of OI for sustainability in social enterprises work?

2. OI for Sustainability in the Social Enterprises

2.1. Innovation for Sustainability in the Social Enterprises

2.2. Thematic Areas of OI

2.3. OI in the Social Enterprises

2.4. Roles of External Partners in OI

3. Methods

3.1. Qualitative Approach Using Case Study

3.2. Samples and Data Analysis

3.3. Case Study Profiles

3.3.1. Social Enterprise A

3.3.2. Social Enterprise B

3.3.3. Social Enterprise C

3.3.4. Social Enterprise D

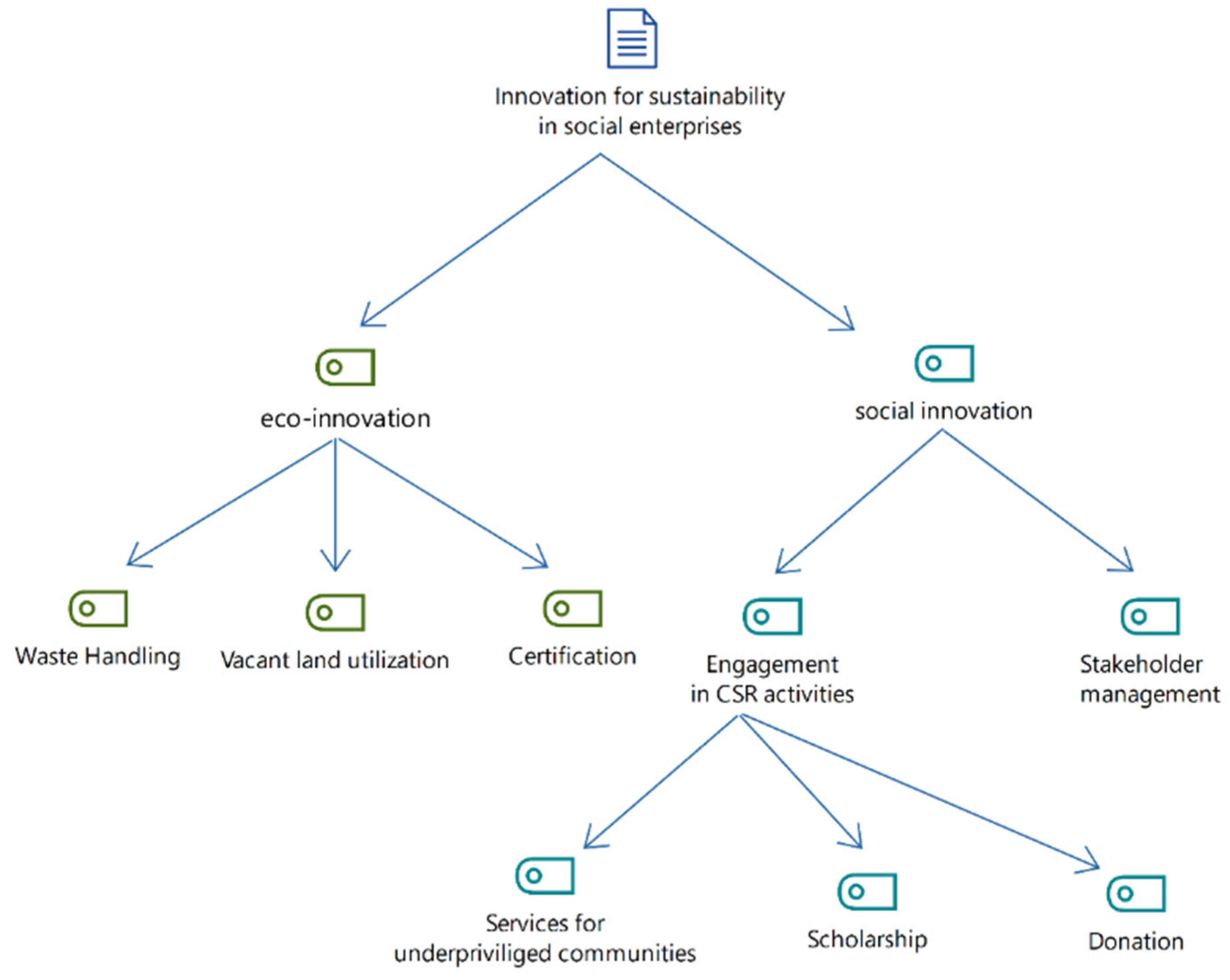

4. Innovation for Sustainability Practices in Social Enterprises

4.1. Eco-Innovation

4.2. Social Innovation

5. Open Social Innovation at the Way of the Sustainability of Social Enterprise

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Adams, R.; Jeanrenaud, S.; Bessant, J.; Denyer, D.; Overy, P. Sustainability-Oriented Innovation: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2016, 18, 180–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, E.G.; Große-Dunker, F. Sustainability-Oriented Innovation. In Encyclopedia of Corporate Social Responsibility; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; pp. 2407–2417. Available online: https://link.springer.com/referenceworkentry/10.1007/978-3-642-28036-8_552 (accessed on 25 July 2022).

- Harsanto, B.; Permana, C.T. Understanding Sustainability-Oriented Innovation (SOI) Using Network Perspective in Asia Pacific and ASEAN: A Systematic Review. JAS J. ASEAN Stud. 2019, 7, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doherty, B.; Haugh, H.; Lyon, F. Social Enterprises as Hybrid Organizations: A Review and Research Agenda. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2014, 16, 417–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battilana, J.; Lee, M. Advancing Research on Hybrid Organizing–Insights from the Study of Social Enterprises. Acad. Manag. Ann. 2014, 8, 397–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chesbrough, H.W. Open Innovation: The New Imperative for Creating and Profiting from Technology; Harvard Business Press: Boston, MA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Bogers, M.; Chesbrough, H.; Moedas, C. Open Innovation: Research, Practices, and Policies. Calif. Manag. Rev. 2018, 60, 5–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maier, D.; Maier, A.; Aşchilean, I.; Anastasiu, L.; Gavriş, O. The Relationship between Innovation and Sustainability: A Bibliometric Review of the Literature. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harsanto, B.; Michaelides, R.; Drummond, H. Sustainability-Oriented Innovation (SOI) in Emerging Economies: A Preliminary Investigation from Indonesia. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE International Conference on Industrial Engineering and Engineering Management (IEEM), Bangkok, Thailand, 16–19 December 2018; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2018; pp. 1553–1557. [Google Scholar]

- Pichlak, M.; Szromek, A.R. Eco-Innovation, Sustainability and Business Model Innovation by Open Innovation Dynamics. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2021, 7, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gumbira, G.; Harsanto, B. Decision Support System for an Eco-Friendly Integrated Coastal Zone Management (ICZM) in Indonesia. Int. J. Adv. Sci. Eng. Inf. Technol. 2019, 9, 1177–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Littlewood, D.; Khan, Z. Insights from a Systematic Review of Literature on Social Enterprise and Networks: Where, How and What Next? Soc. Enterp. J. 2018, 14, 390–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bigliardi, B.; Filippelli, S. Sustainability and Open Innovation: Main Themes and Research Trajectories. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Park, G.; Yoon, B.; Park, J. Open Innovation in SMEs—An Intermediated Network Model. Res. Policy 2010, 39, 290–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odriozola-Fernández, I.; Berbegal-Mirabent, J.; Merigó-Lindahl, J.M. Open Innovation in Small and Medium Enterprises: A Bibliometric Analysis. J. Organ. Chang. Manag. 2019, 32, 533–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azis, Y.; Darun, M.R.; Kartini, D.; Bernik, M.; Harsanto, B. A Model of Managing Innovation of SMEs in Indonesia Creative Industries. Int. J. Bus. Soc. 2017, 18, 391–408. [Google Scholar]

- Widianto, S.; Harsanto, B. The Impact of Transformational Leadership and Organizational Culture on Firm Performance in Indonesia SMEs. In The Palgrave Handbook of Leadership in Transforming Asia; Muenjohn, N., McMurray, A., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan UK: London, UK, 2017; pp. 503–517. [Google Scholar]

- Hervas-Oliver, J.-L.; Sempere-Ripoll, F.; Boronat-Moll, C. Technological Innovation Typologies and Open Innovation in SMEs: Beyond Internal and External Sources of Knowledge. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2021, 162, 120338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meili, R.; Shearmur, R. Diverse Diversities—Open Innovation in Small Towns and Rural Areas. Growth Chang. 2019, 50, 492–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chesbrough, H.; Bogers, M. Explicating Open Innovation: Clarifying an Emerging Paradigm for Understanding Innovation. In New Frontiers in Open Innovation; Chesbrough, H., Vanhaverbeke, W., West, J., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Gassmann, O.; Enkel, E.; Chesbrough, H. The Future of Open Innovation. R&D Management. R&D Manag. 2010, 40, 213–221. [Google Scholar]

- Freeman, C. The Economics of Industrial Innovation; Penguin Books: London, UK, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- West, J.; Salter, A.; Vanhaverbeke, W.; Chesbrough, H. Open Innovation: The next Decade. Res. Policy 2014, 43, 805–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teece, D.J. Profiting Form Technological Innovation: Implications for Integration, Collaboration, Licensing and Public Policy. Res. Policy 1986, 15, 285–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatimah, Y.A.; Govindan, K.; Murniningsih, R.; Setiawan, A. Industry 4.0 Based Sustainable Circular Economy Approach for Smart Waste Management System to Achieve Sustainable Development Goals: A Case Study of Indonesia. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 269, 122263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fichter, K.; Paech, N. Nachhaltigkeitsorientiertes Innovationsmanagement: Prozessgestaltung Unter Besonderer Berücksichtigung von Internet-Nutzungen: Endbericht Der Basisstudie 4 Des Vom BMF Geförderten Vorhabens" SUstainable Markets EMERge"(SUMMER); Univ., Lehrstuhl für Allg. Betriebswirtschaftslehre, Unternehmensführung und Betriebliche Umweltpolitik: Berlin/Oldenburg, Germany, 2004; Available online: https://www.borderstep.de/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/Fichter-Paech-Nachhaltigkeitsorientiertes_Innovationsmanagement-2003.pdf (accessed on 25 July 2022).

- Hall, J.; Vredenburg, H. The Challenges of Innovating for Sustainable Development. MIT Sloan Manag. Rev. 2003, 45, 61–68. [Google Scholar]

- Horbach, J.; Rammer, C.; Rennings, K. Determinants of Eco-Innovations by Type of Environmental Impact-The Role of Regulatory Push/Pull, Technology Push and Market Pull. Ecol. Econ. 2012, 78, 112–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jänicke, M. “Green Growth”: From a Growing Eco-Industry to Economic Sustainability. Energy Policy 2012, 48, 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rauter, R.; Globocnik, D.; Perl-Vorbach, E.; Baumgartner, R.J. Open Innovation and Its Effects on Economic and Sustainability Innovation Performance. J. Innov. Knowl. 2019, 4, 226–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, R.K. Qualitative Research from Start to Finish; Guilford Publications: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harsanto, B. The First-Three-Month Review of Research on Covid-19: A Scientometrics Analysis. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Engineering, Technology and Innovation (ICE/ITMC), Cardiff, UK, 15–17 June 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Harsanto, B.; Mulyana, A.; Faisal, Y.A.; Mellandhia, V. Inovasi Lingkungan Dan Dampak Pandemi: Studi Kasus Pada UMKM Makanan Dan Minuman. J. Inov. Has. Pengabdi. Masy. JIPEMAS 2022, 5, 268–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chesbrough, H.; Di Minin, A. Open Social Innovation. New Front. Open Innov. 2014, 16, 301–315. [Google Scholar]

- Yun, J.J.; Park, K.B.; Im, C.J.; Shin, C.H.; Zhao, X. Dynamics of Social Enterprises—Shift from Social Innovation to Open Innovation. Sci. Technol. Soc. 2017, 22, 425–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGahan, A.M.; Bogers, M.L.A.M.; Chesbrough, H.; Holgersson, M. Tackling Societal Challenges with Open Innovation. Calif. Manage. Rev. 2021, 63, 49–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, S.; Smart, P. Exploring Open Innovation Practice in Firm-nonprofit Engagements: A Corporate Social Responsibility Perspective. R&d Manag. 2009, 39, 394–409. [Google Scholar]

- Hsu, H.Y.; Liu, F.H.; Tsou, H.T.; Chen, L.J. Openness of Technology Adoption, Top Management Support and Service Innovation: A Social Innovation Perspective. J. Bus. Ind. Mark. 2019, 34, 575–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gould, R.W. Open Innovation and Stakeholder Engagement. J. Technol. Manag. Innov. 2012, 7, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mladenow, A.; Bauer, C.; Strauss, C. Social Crowd Integration in New Product Development: Crowdsourcing Communities Nourish the Open Innovation Paradigm. Glob. J. Flex. Syst. Manag. 2014, 15, 77–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidthuber, L.; Piller, F.; Bogers, M.; Hilgers, D. Citizen Participation in Public Administration: Investigating Open Government for Social Innovation. R&D Manag. 2019, 49, 343–355. [Google Scholar]

- Randhawa, K.; Wilden, R.; West, J. Crowdsourcing without Profit: The Role of the Seeker in Open Social Innovation. R&D Manag. 2019, 49, 298–317. [Google Scholar]

| Innovation for Sustainability in Social Enterprises | ||

| Themes | Sub-Themes | Units of Meaning Structure |

| Eco-innovation | Waste handling | ...from an environmental perspective, there is a recycle for vegetable waste. An example is carrots, carrots that we harvest, the leaves we do not throw away. We usually chop these leaves or cut into pieces to be used as feed for sheep or cattle or used as silage.… (SE_B) …for laundry, in the washing of jeans, there is a certain waste that is wasted, we use some kind of remedy to neutralize it. In the clinic, we also have our own WWTP… (SE_C) |

| Vacant land utilization | … we managed the former iron sand excavation into a shrimp pond. It can be seen that we help the government with land management which ultimately becomes an economic solution for the surrounding community… (SE_A) | |

| Certification | …especially now that we are preparing for BRCGS certification, from upstream we have prepared JAP, PSAT, but in the warehouse we have prepared it for now. This certification will guarantee food safety so that consumers do not have to worry anymore... (SE_B) …we already had halal meat and the slaughter process was covered and aired in the store. The meat has also been halal certified and we attach it... (SE_D) | |

| Social innovation | Engagement in CSR activities | …from the social side, we collaborate with RT, RW, and kelurahan to open cheap basic necessities. Later, we will facilitate these cheap basic necessities. Yesterday we had cooperation with social institutions in the internals to make cheap food packages for the disabled… (SE_B) |

| Stakeholder management | …initially, the members of the cooperative were only 300 people, most of whom came from internal boarding schools. At this time, its members reached 19,000 people and most of them were from this city… (SE_A) We send vegetables in modern markets outside the traditional market... we involve the surrounding community, market traders, farmers, and others... (SE_B) | |

| OI mechanism | ||

| Actors | Sub-actors | Units of meaning structure |

| Internal actors | Social enterprises’ management | …in 2019, when there were structural changes where there were four deputy leaders among of them has background of economics… (the management) more professional… (SE_A) …the management also received grants from Japan and various medical devices were also upgraded a lot (mid-pandemic). Therefore, people’s confidence in coming to the clinic began to grow. This Japanese grant is for its medical device facilities… (SE_C) |

| External actors | Religious leaders in the boarding school | …Our current religious leaders, he is indeed an entrepreneur. Our deceased leader was also an entrepreneur… (SE_A) Since the leadership of one of our leaders, this boarding school has undergone a lot of changes. The first thing to do is to change the name, which means good cooperation… (SE_B) |

| Alumni of the boarding school | … we are working in agriculture… plus that as much as 80% of this boarding school graduates are farmers… (SE_B) …there are alumni who offer help because they already have their own legal entity… The team had thought of creating a marketplace because there are many alumni who do business everywhere... (SE_C) | |

| Market/suppliers | …In 1994, we began to be taught how to sort, grading, packing, labeling, giving barcodes, controlling bills, disbursing funds, and so on. From 1994 until now, we still have a good relationship with the modern market and this has been going on for more than 27 years… (SE_B) | |

| Government/state-owned enterprises | …one of business units gets help from state owned enterprise engaged in oil and gas business. It used to be running and in terms of sales, it was also not bad… (SE_C) | |

| Higher education institutions | …in the end, we together with the central bank and one of well-known management and business school to collaborate to create an online application... (SE_B) …we are under the supervision of the biggest agricultural higher education in Indonesia. The role of the university to plunge into the cottages provide management guidance and collaborate… (SE_C). | |

| Foreign NGOs | …the grant scheme, we put forward a proposal with 70% of medical devices and 30% of buildings with the condition that within 5 years no change is permitted… (SE_C) | |

| Local NGOs | There used to be LP2S and now it is merged into a subsidiary that trains. GSP (formerly called DTSP) is a company, the company’s shares are owned by cooperatives, foundations, and the private sector, as well as leaders of pesantren (SE_D). For innovation, we have cooperation in the development of the application. We also improve the integration system. In the past, the financial system was still manual, and now we are trying to integrate it through collaboration with third party. (SE_D) | |

| Private enterprises | We send vegetables in modern markets outside the traditional market, such as private modern market of X, Y, Z, etc. (SE_B) | |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Harsanto, B.; Mulyana, A.; Faisal, Y.A.; Shandy, V.M. Open Innovation for Sustainability in the Social Enterprises: An Empirical Evidence. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2022, 8, 160. https://doi.org/10.3390/joitmc8030160

Harsanto B, Mulyana A, Faisal YA, Shandy VM. Open Innovation for Sustainability in the Social Enterprises: An Empirical Evidence. Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity. 2022; 8(3):160. https://doi.org/10.3390/joitmc8030160

Chicago/Turabian StyleHarsanto, Budi, Asep Mulyana, Yudi Ahmad Faisal, and Venny Mellandhia Shandy. 2022. "Open Innovation for Sustainability in the Social Enterprises: An Empirical Evidence" Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity 8, no. 3: 160. https://doi.org/10.3390/joitmc8030160

APA StyleHarsanto, B., Mulyana, A., Faisal, Y. A., & Shandy, V. M. (2022). Open Innovation for Sustainability in the Social Enterprises: An Empirical Evidence. Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity, 8(3), 160. https://doi.org/10.3390/joitmc8030160