An Intelligent Water Level Estimation System Considering Water Level Device Gauge Image Recognition and Wireless Sensor Networks

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Related Works

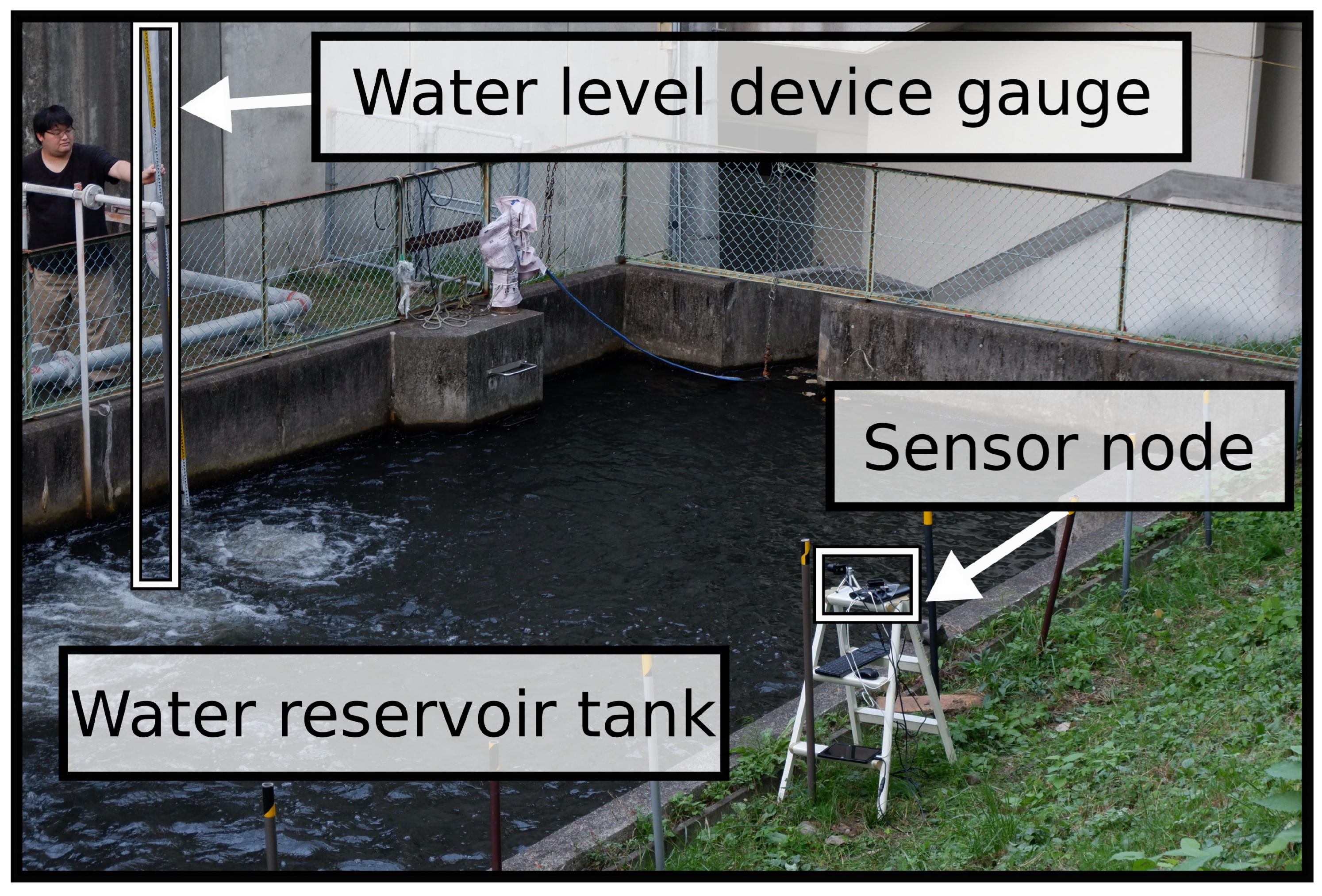

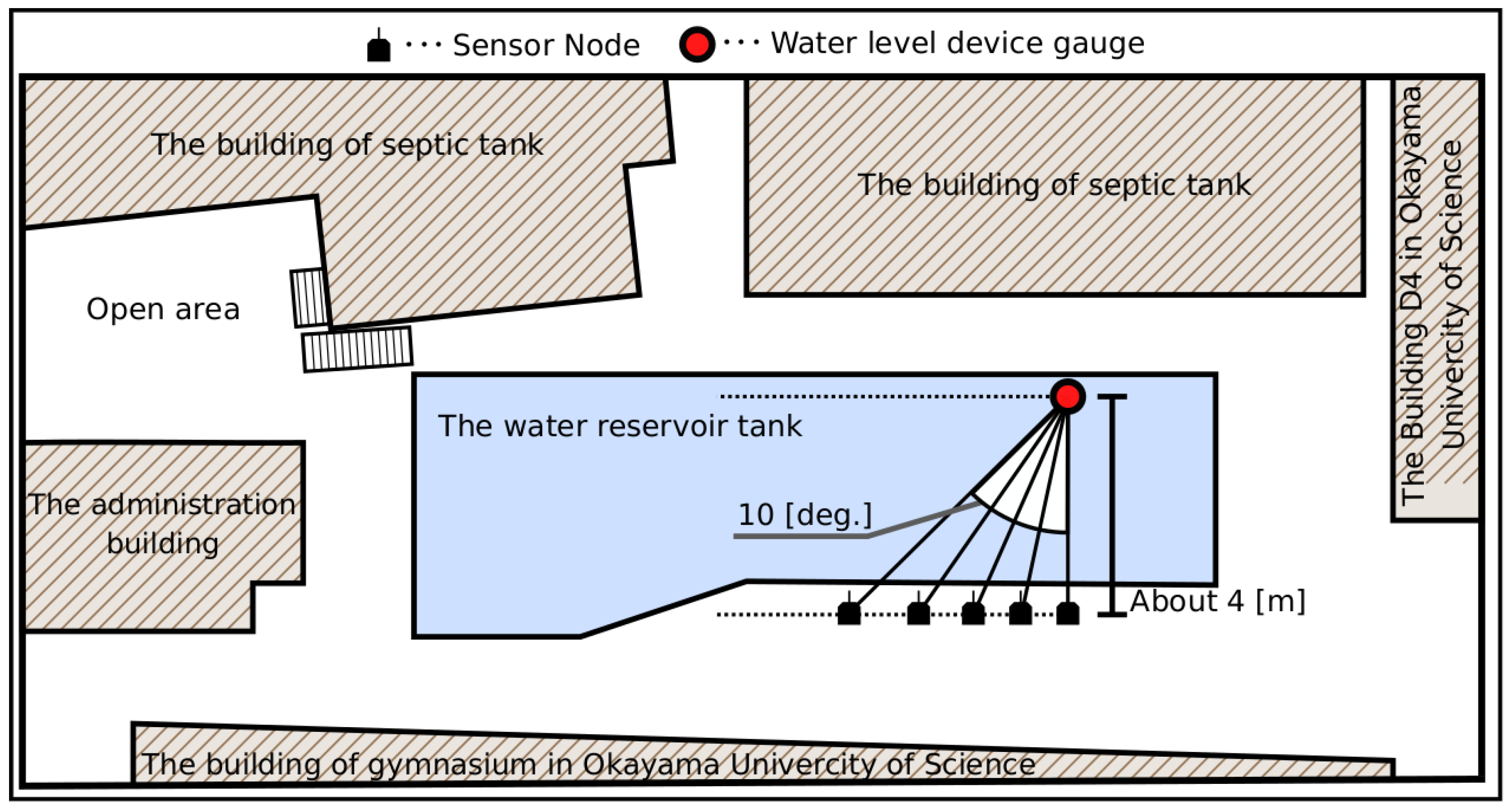

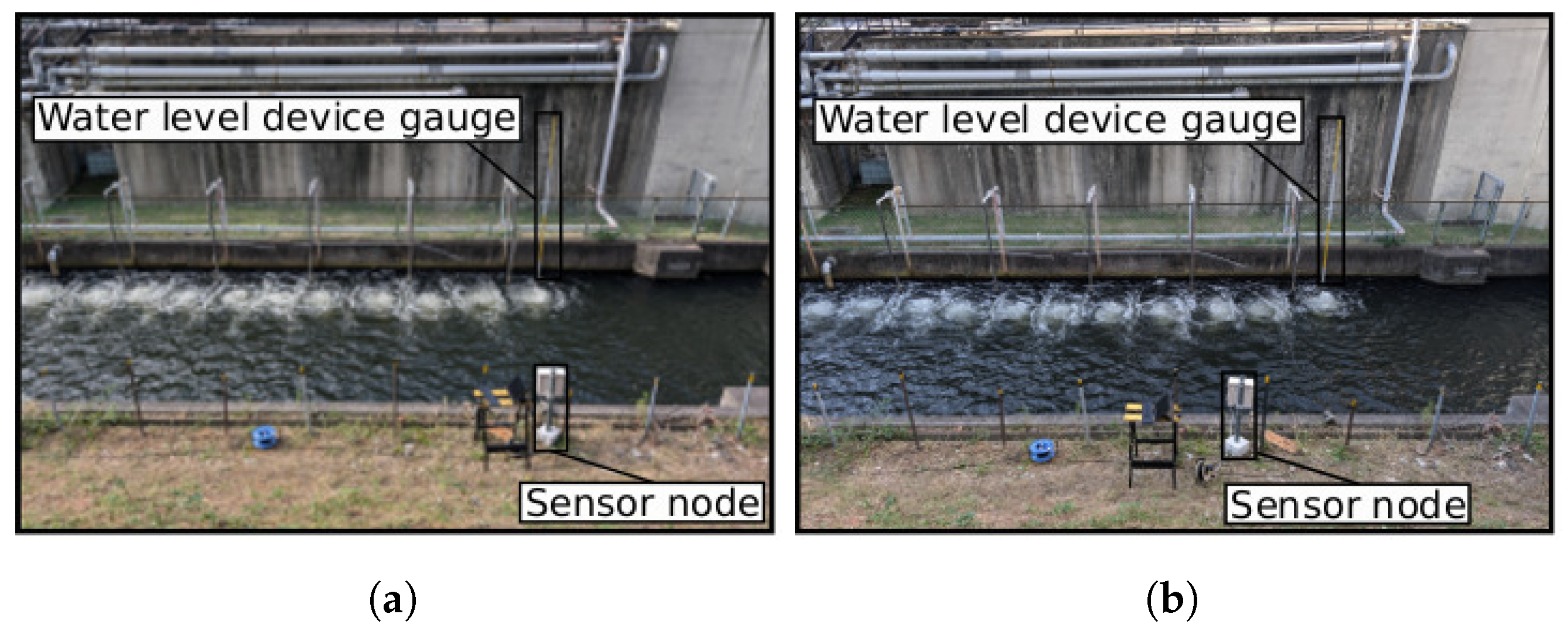

3. Proposed System

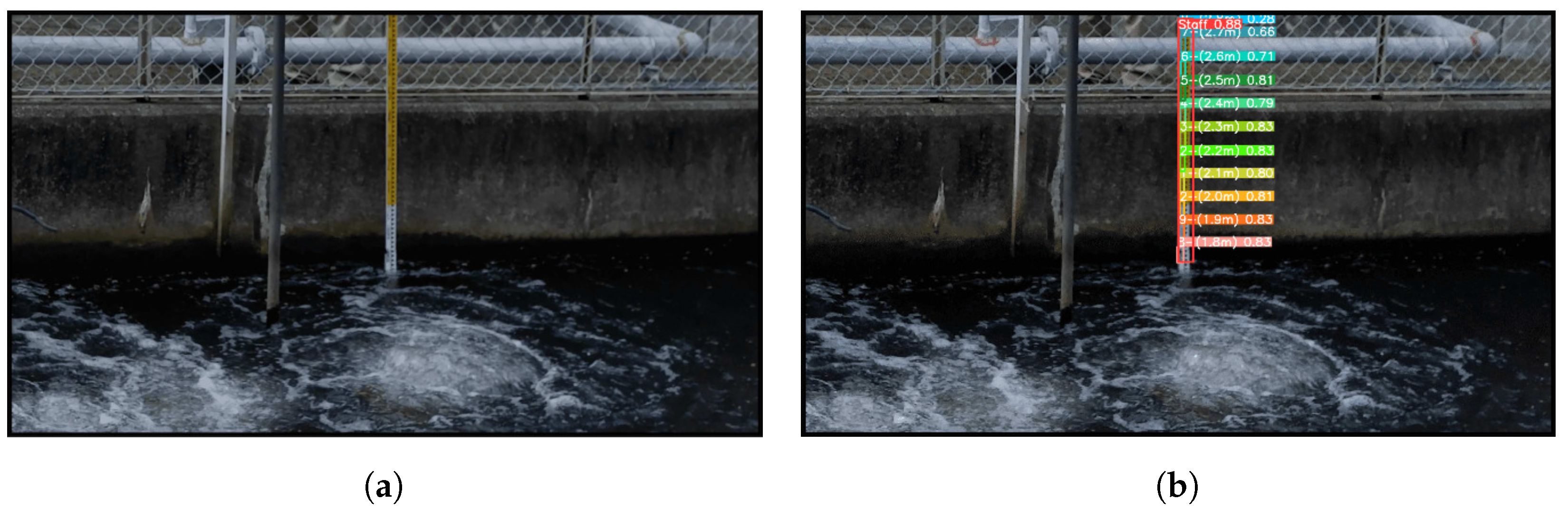

3.1. Design of Object Recognition-Based Water Level Estimation System

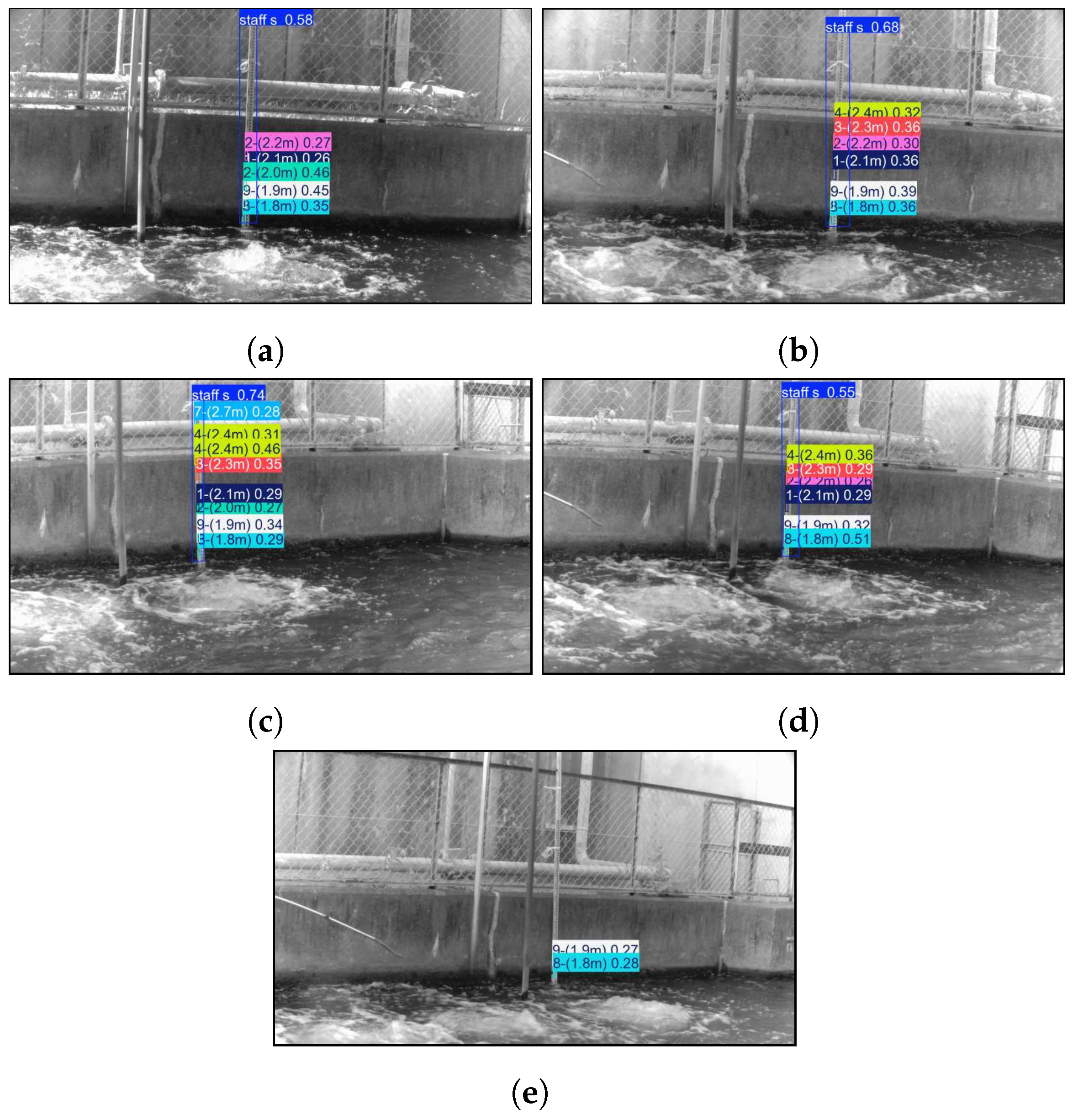

3.2. Example of Water Level Estimation Using Proposed System

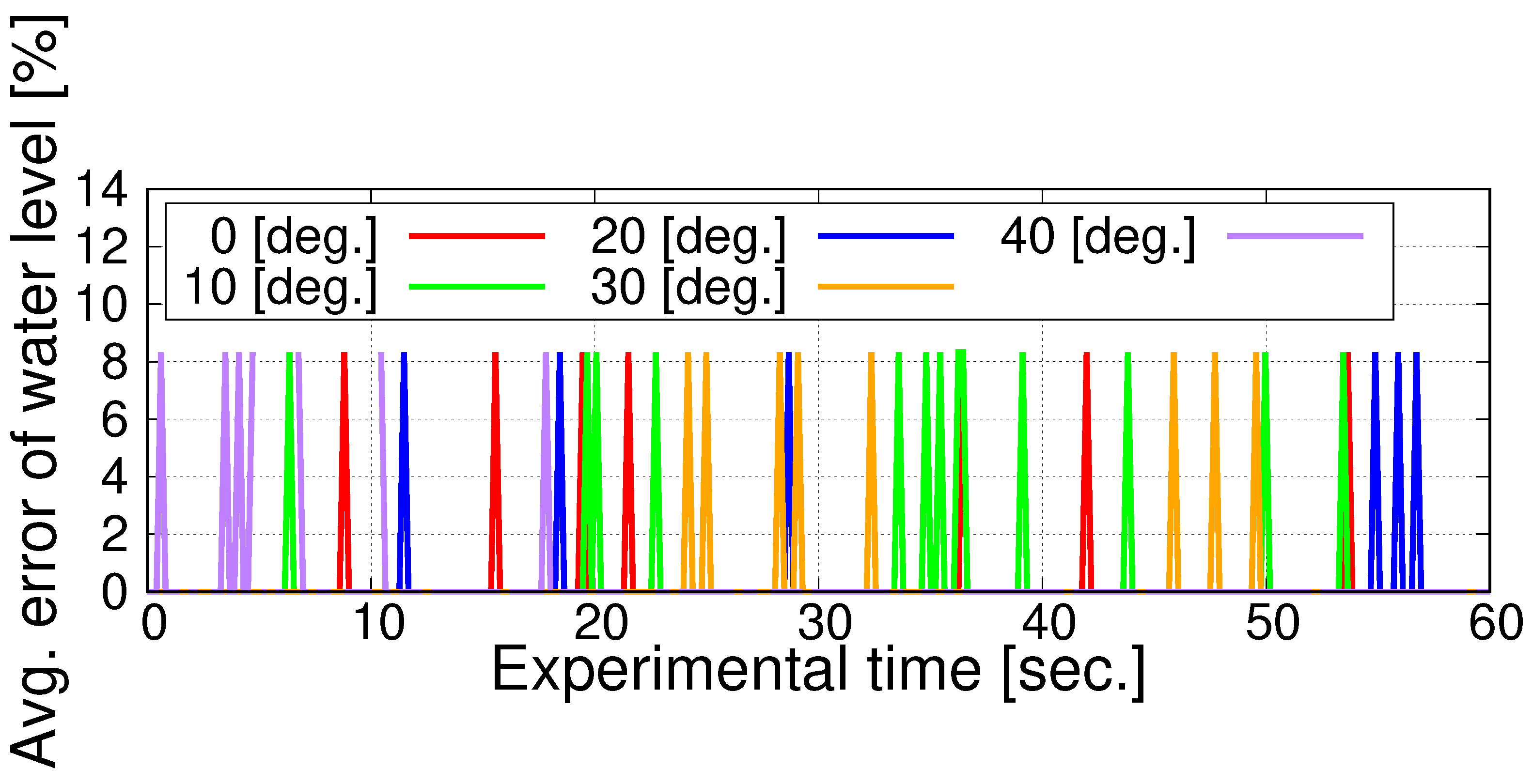

4. Performance Evaluation

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

- The proposed system was found to be able to estimate the water level by using the image-based object recognition of the numbers and symbols printed on the water level device gauge.

- The experimental results confirm that the proposed system is capable of estimating transitions between the camera and the water level device gauge from 0 [deg.] to 40 [deg.].

- The proposed system can reduce the workload of reservoir and river managers.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (IFRC). World Disasters Report 2022; International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Cretaux, J.F. Instrumentation and Measurement Technologies for Water Cycle Management; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, X.; Zhu, A.; Li, Q.; Chen, R. Improving the Response to Inland Flooding. Science 2021, 374, 831–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, D.; Paul, B. A Levee Breach Induced by Internal Erosion in Western Australia. Q. J. Eng. Geol. Hydrogeol. 2021, 55, qjegh2021-037. [Google Scholar]

- Dolojan, N.L.J.; Moriguchi, S.; Hashimoto, M.; Xuan Tinh, N.; Tanaka, H.; Terada, K. Hydrologic-geotechnical Modelling of Shallow Landslide and Flood Hazards Caused by Heavy Rainfall. Eng. Geol. 2023, 323, 107184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusudo, T.; Yamamoto, A.; Kimura, M.; Matsuno, Y. Development and Assessment of Water-level Prediction Models for Small Reservoirs Using a Deep Learning Algorithm. Water 2021, 14, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Liu, Z.; Wang, L.; Dou, M.; Chen, J.; Li, H. Natural Disaster Monitoring with Wireless Sensor Networks: A Case Study of Data-intensive Applications upon Low-cost Scalable Systems. Mob. Netw. Appl. 2021, 18, 651–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yawut, C.; Kilaso, S. A Wireless Sensor Network for Weather and Disaster Alarm Systems. In Proceedings of the 2011 International Conference on Electrical Engineering and Informatics, Bangkok, Thailand, 28–29 May 2011; pp. 155–159. [Google Scholar]

- Tanyingyong, V.; Olsson, R.; Hidell, M.; Sjödin, P. Scalable IoT Sensing Systems with Dynamic Sinks. IEEE Internet Things J. 2022, 9, 7211–7227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruzada, C.J.; Francisco, P.; Loyola, R.; Asaba, H.; Flores, F.K.; Peradilla, M. Proposed Real-time Data Aggregation Scheme for Clusterbased WSN Sensor Nodes. In Proceedings of the 18th Asian Internet Engineering Conference (AINTEC), Hanoi, Vietnam, 12–14 December 2023; pp. 54–61. [Google Scholar]

- Qiao, G.; Yang, M.; Wang, H. A Water Level Measurement Approach Based on YOlOv5s. Sensors 2022, 22, 3714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lo, S.W.; Wu, J.H.; Lin, F.P.; Hsu, C.H. Visual Sensing for Urban Flood Monitoring. Sensors 2015, 15, 20006–20029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Zhou, Y.; Liu, H.; Zhang, L.; Wang, H. Visual Measurement of Water Level Under Complex Illumination Conditions. Sensors 2019, 19, 4141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, M.; Wan, Z.; Yao, C.; Chen, K.; Bai, X. Real-time Scene Text Detection with Differentiable Binarization. In Proceedings of the AAAI 34th Conference on Artificial Intelligence, New York, NY, USA, 7–12 February 2020; pp. 11474–11481. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, X.; Yao, H.; Qi, Y.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, S. Scene Text Recognition Via Transformer. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2003.08077. [Google Scholar]

- Atienza, R. Vision Transformer for Fast and Efficient Scene Text Recognition. In Proceedings of the 16th International Conference on Document Analysis and Recognition (ICDAR), Lausanne, Switzerland, 5–10 September 2021; pp. 319–334. [Google Scholar]

- Kukreja, V.; Kumar, D.; Kaur, A. GAN-based Synthetic Data Augmentation for Increased CNN Performance in Vehicle Number Plate Recognition. In Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Electronics, Communication and Aerospace Technology (ICECA), Coimbatore, India, 5–7 November 2020; pp. 1190–1195. [Google Scholar]

- Dang, L.T.A.; Ngoc, V.D.; Thien Vu, P.C.L.; Truong, N.N.; Trinh, T.D. Vietnam Vehicle Number Recognition Based on An Improved CRNN with Attention Mechanism. Int. J. Intell. Transp. Syst. Res. 2024, 22, 374–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Hou, J.; Huang, C. Basin Scale Soil Moisture Estimation with Grid SWAT and LESTKF Based on WSN. Sensors 2023, 24, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sendra, S.; Parra, L.; Jimenez, J.M.; Garcia, L.; Lloret, J. LoRa-based Network for Water Quality Monitoring in Coastal Areas. Mob. Netw. Appl. 2023, 28, 65–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.A.J.; Jasim, M.N.; Al-Saad, S.N. Novel Smart Water Quality Monitoring System for Iraqi Rivers and Marshes. In Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on Environment and Sustainability (ICEST), Anbar, Iraq, 21 July 2023; pp. 19–30. [Google Scholar]

- Kalyanapu, A.; Owusu, C.; Wright, T.; Datta, T. Low-Cost Real-Time Water Level Monitoring Network for Falling Water River Watershed: A Case Study. Geosciences 2023, 13, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olatinwo, S.O.; Joubert, T.H. Efficient Energy Resource Utilization in a Wireless Sensor System for Monitoring Water Quality. EURASIP J. Wirel. Commun. Netw. 2019, 2019, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langhammer, J. Flood Simulations Using a Sensor Network and Support Vector Machine Model. Water 2023, 15, 2004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Shafeiy, E.; Alsabaan, M.; Ibrahem, M.I.; Elwahsh, H. Real-time Anomaly Detection for Water Quality Sensor Monitoring Based on Multivariate Deep Learning Technique. Sensors 2023, 23, 8613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosero-Montalvo, P.D.; López-Batista, V.F.; Riascos, J.A.; Peluffo-Ordóñez, D.H. Intelligent WSN System for Water Quality Analysis Using Machine Learning Algorithms: A case Study (Tahuando River from Ecuador). Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 1988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Q.; Yang, F.; Yu, X.; Wang, X.; Xu, J.; Cao, N.; Zhang, H.; Wang, L.; Yu, J. Environment Adaptive Deployment of Water Quality Sensor Networks. Int. J. Intell. Syst. 2022, 37, 2911–2925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, Y.; Walingo, T. Smart Water Quality Monitoring with IoT Wireless Sensor Networks. Sensors 2024, 24, 2871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Süzen, A.A.; Duman, B.; Şen, B. Benchmark Analysis of Jetson TX2, Jetson Nano and Raspberry Pi Using Deep-CNN. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Congress on Human-Computer Interaction, Optimization and Robotic Applications, Ankara, Turkey, 26–27 June 2020; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Uddin, M.I.; Alamgir, M.S.; Rahman, M.M.; Bhuiyan, M.S.; Mora, M.A. AI Traffic Control System Based on Deepstream and IoT Using NVIDIA Jetson Nano. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Robotics, Electrical and Signal Processing Techniques, Dhaka, Bangladesh, 5–7 January 2021; pp. 115–119. [Google Scholar]

- Idoudi, M.; Bourennane, E.-B.; Grayaa, K. Wireless Visual Sensor Network Platform for Indoor Localization and Tracking of a Patient for Rehabilitation Task. IEEE Sens. J. 2018, 18, 5915–5928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, P.F.; Xiao, F.; Sha, C.; Huang, H.P.; Wang, R.C.; Xiong, N.-X. Node Scheduling Strategies for Achieving Full-view Area Coverage in Camera Sensor Networks. Sensors 2018, 17, 1303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Redmon, J.; Divvala, S.; Girshick, R.; Farhadi, A. You Only Look Once: Unified, Real-time Object Detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE 29th Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Washington, DC, USA, 23–28 June 2016; pp. 779–788. [Google Scholar]

- Duong-Nguyen, T.; Hoang, T.; Vo, P.; Le, H. Water Level Estimation Using Sentinel-1 Synthetic Aperture Radar Imagery and Digital Elevation Models. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2012.07627. [Google Scholar]

- Asano, M.; Yamaguchi, H.; Okamoto, H. Cavity optomechanical liquid level meter using a twin-microbottle resonator. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2401.12529. [Google Scholar]

- Kossieris, S.; Tsiakos, V.; Tsimiklis, G.; Amditis, A. Inland Water Level Monitoring from Satellite Observations: A Scoping Review of Current Advances and Future Opportunities. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yukawa, C.; Oda, T.; Sato, T.; Hirota, M.; Katayama, K.; Barolli, L. An Intelligent Water Level Estimation System Considering Water Level Device Gauge Image Recognition and Wireless Sensor Networks. J. Sens. Actuator Netw. 2025, 14, 13. https://doi.org/10.3390/jsan14010013

Yukawa C, Oda T, Sato T, Hirota M, Katayama K, Barolli L. An Intelligent Water Level Estimation System Considering Water Level Device Gauge Image Recognition and Wireless Sensor Networks. Journal of Sensor and Actuator Networks. 2025; 14(1):13. https://doi.org/10.3390/jsan14010013

Chicago/Turabian StyleYukawa, Chihiro, Tetsuya Oda, Takeharu Sato, Masaharu Hirota, Kengo Katayama, and Leonard Barolli. 2025. "An Intelligent Water Level Estimation System Considering Water Level Device Gauge Image Recognition and Wireless Sensor Networks" Journal of Sensor and Actuator Networks 14, no. 1: 13. https://doi.org/10.3390/jsan14010013

APA StyleYukawa, C., Oda, T., Sato, T., Hirota, M., Katayama, K., & Barolli, L. (2025). An Intelligent Water Level Estimation System Considering Water Level Device Gauge Image Recognition and Wireless Sensor Networks. Journal of Sensor and Actuator Networks, 14(1), 13. https://doi.org/10.3390/jsan14010013