Pharmacy Students’ Perceptions of the Pharmacist Role: An Arts-Informed Approach to Professional Identity Formation

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Qualitative Study Design

2.2. Context

2.3. Recruitment

2.4. Research Team and Reflexivity

2.5. Data Collection

2.6. Data Analysis

2.7. Rigor

3. Results

3.1. Apothecary

“[A] pharmacist is someone who is professional. Always in a lab coat, almost like a scientist. Always ready to help someone with questions [and] to serve the community.”[2025-Y1-035].

“A pharmacist should be passionate to help. I believe that pharmacists, as [the] most accessible part of healthcare, are responsible to share their medical knowledge in [the] best way possible to help those in need and that comes with the love for medicine, pharmacy, and society.”[2025-Y1-070].

3.2. Dispenser

“Pharmacists have a significant role in patient care beyond just dispensing medications.”[2025-Y1-018].

“I drew a pharmacist next to a vial and computer. The vial represents the pharmacist’s medication knowledge. The computer represents patient information collected by a pharmacist.”[2025-Y1-003].

“White coat = professional, pill = dispensing medication, syringe = admin[istration] of injections, mortar & pestle = compounding, clipboard = clinical aspect.”[2025-Y1-006].

“The pharmacist is a professional, but welcoming face for people to interact with. It is important for patients to have pharmacists to ask them for medical information.”[2025-Y1-087].

3.3. Merchandiser

“My pharmacist that I drew is a female and she owns her own pharmacy. She’s very polite and always does her best for patients.”[2025-Y1-050].

“Serve your community, resolve problems, represent and advance health care.”[2025-Y1-100].

3.4. Expert Advisor

“A doctor and a pharmacist are shown discussing potential treatment options. The pharmacist is providing their input.”[2025-Y1-033].

“Pharmacists have a role in providing expertise to patients and other health care providers in the realm of pharmaceutics and pharmacotherapy. Their ultimate goal is to enhance patients’ well-being.”[2025-Y1-086].

“The drawing illustrates people applauding a health care professional (e.g., physician, nurse), while the pharmacist is depicted as pulling strings, symbolizing their work conducted behind the scenes.”[2025-Y1-039].

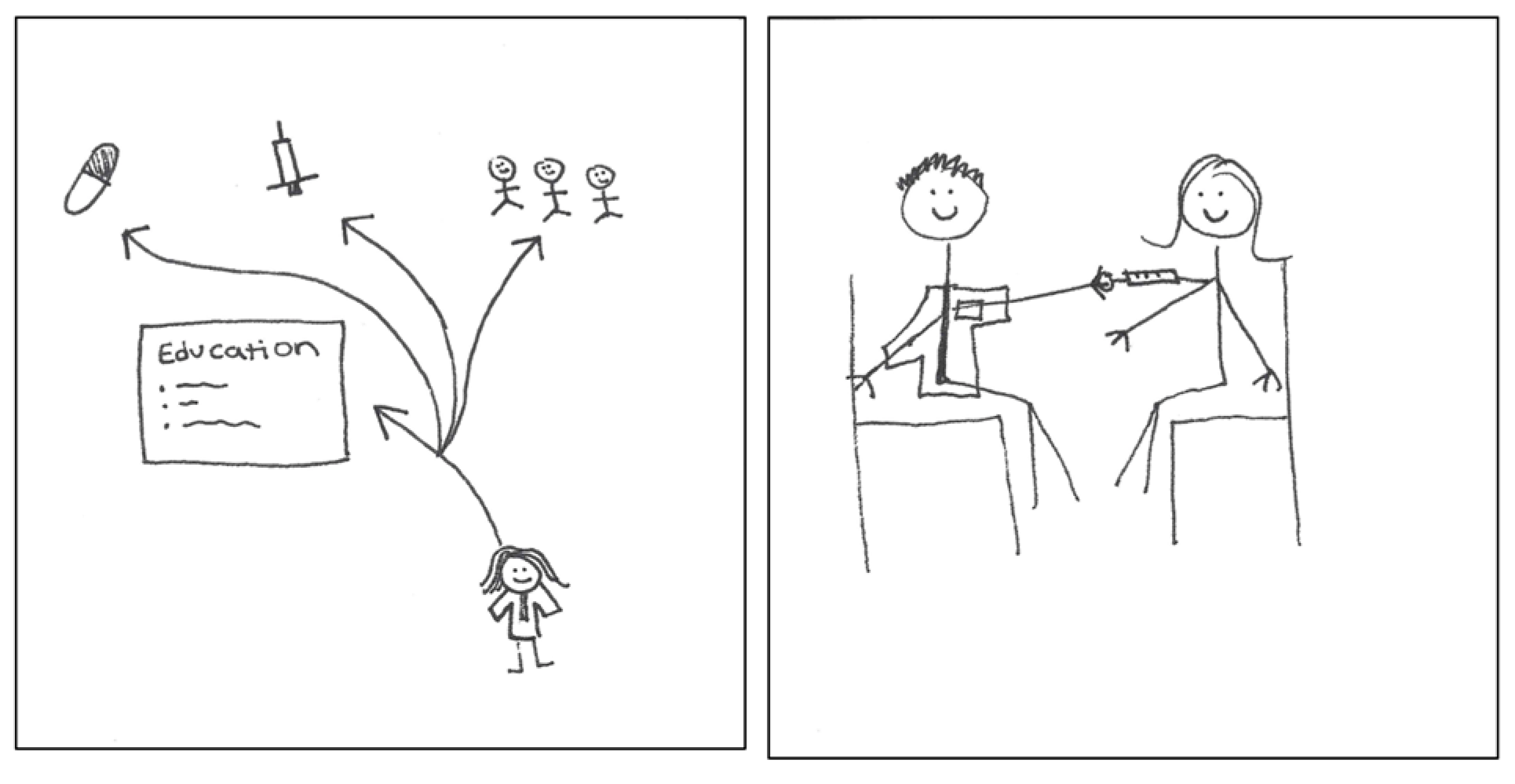

3.5. Health Care Provider

“Pharmacists provide care to patients in need of assistance through medication.”[2025-Y1-023].

“I’ve drawn a pharmacist watering a wilted plant to represent them helping an ill patient replenish and become healthy. They are also holding hands with another professional to show they aren’t alone. We work together with other healthcare professionals to increase public health.”[2025-Y1-013].

“Every patient has their own puzzle. We need to find your piece.”[2025-Y1-077].

“Pharmacists play a major role in giving immunizations to help protect our communities.”[2025-Y1-016].

“I drew a pharmacist prescribing medication to a patient.”[2025-Y1-064].

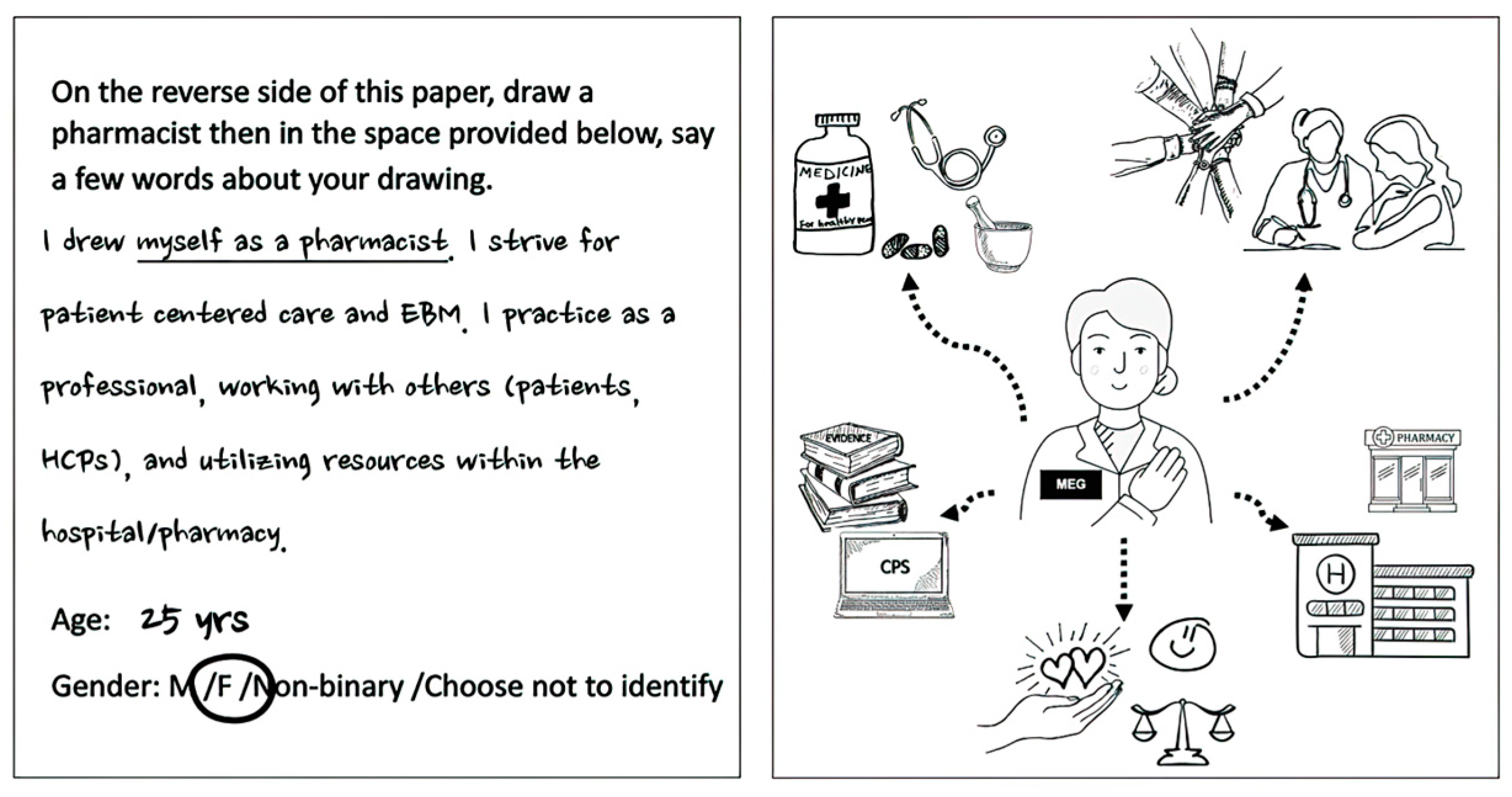

3.6. Multi-Faceted Professional

“Patient care, research, education, drug synthesis, consultation, practice, expansion.”[2025-Y1-071].

“I highlighted the roles of pharmacists in communication (with other healthcare workers, care homes, and neighbourhoods) and general tasks like dispensing and answering questions and empathizing/checking for alarming interactions. Also they advocate and consult patients and for the profession.”[2025-Y1-074].

“In the center, I drew a signature white coat of a pharmacist. Around it I drew lab materials (compounding), books (academia), giving drugs (practice), and a conference (professional development).”[2025-Y1-020].

“I drew a few different roles that popped up when thinking about a pharmacist, such as: dispensing medication, compounding, helping patients, etc.”[2025-Y1-082].

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Noble, C.; O’Brien, M.; Coombes, I.; Shaw, P.N.; Nissen, L.; Clavarino, A. Becoming a pharmacist: Students’ perceptions of their curricular experience and professional identity formation. Curr. Pharm. Teach. Learn 2014, 6, 327–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mylrea, M.F.; Gupta, T.S.; Glass, B.D. Design and evaluation of a professional identity development program for pharmacy students. Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 2019, 83, 1320–1327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janke, K.K.; Bloom, T.J.; Boyce, E.G.; Johnson, J.L.; Kopacek, K.; O’Sullivan, T.A.; Petrelli, H.M.W.; Steeb, D.R.; Ross, L.J. A pathway to professional identity formation: Report of the 2020–2021 AACP student affairs standing committee. Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 2021, 85, 1128–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mylrea, M.F.; Gupta, T.S.; Glass, B.D. Professionalization in pharmacy education as a matter of identity. Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 2015, 79, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, J.L.; Arif, S.; Bloom, T.J.; Isaacs, A.N.; Moseley, L.E.; Janke, K.K. Preparing pharmacy educators as expedition guides to support professional identity formation in pharmacy education. Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 2023, 87, ajpe8944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodrick, E.; Reay, T. Constellations of institutional logics: Changes in the professional work of pharmacists. Work Occup. 2011, 38, 372–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burrows, J.; Dall’Alba, G.; Caze, A.L. Becoming pharmacists: Students’ understanding of pharmacy practice at graduation from an Australian University. Curr. Pharm. Teach. Learn 2016, 8, 729–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarvis-Selinger, S.; Macneil, K.A.; Costello, G.R.L.; Lee, K.; Holmes, C.L. Understanding professional identity formation in early clerkship: A novel framework. Acad. Med. 2019, 94, 1574–1580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watson, K.E.; Schindel, T.J.; Barsoum, M.E.; Kung, J.Y. COVID the Catalyst for Evolving Professional Role Identity? A Scoping Review of Global Pharmacists’ Roles and Services as a Response to the COVID-19 Pandemic. Pharmacy 2021, 9, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, B.; Carroll, B. Re-viewing ‘role’ in processes of identity construction. Organization 2008, 15, 29–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibarra, H. Provisional selves: Experimenting with image and identity in professional adaptation. Admin. Sci. Q. 1999, 44, 764–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratt, M.G.; Rockmann, K.W.; Kaufmann, J.B. Constructing professional identity: The role of work and identity learning cycles in the customization of identity among medical residents. Acad. Manag. J. 2006, 49, 235–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weick, K.E. Sensemaking in Organizations; SAGE Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Alvesson, M.; Lee Ashcraft, K.; Thomas, R. Identity matters: Reflections on the construction of identity scholarship in organization studies. Organization 2008, 15, 5–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dall’Alba, G. Learning to Be Professionals; Springer: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Chreim, S.; Williams, B.E.; Hinings, C.R. Interlevel influences on the reconstruction of professional role identity. Acad. Manag. J. 2007, 50, 1515–1539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pottie, K.; Haydt, S.; Farrell, B.; Kennie, N.; Sellors, C.; Martin, C.; Dolovich, L. Pharmacist’s identity development within multidisciplinary primary health care teams in Ontario: Qualitative results from the IMPACT (†) project. Res. Social. Adm. Pharm. 2009, 5, 319–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burr, V. Social Constructionism, 2nd ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Reay, T.; Goodrick, E.; Waldorff, S.B.; Casebeer, A. Getting leopards to change their spots: Co-creating a new professional role identity. Acad. Manag. J. 2017, 60, 1043–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenwood, R.; Suddaby, R.; Hinings, C.R. Theorizing change: The role of professional associations in the transformation of institutionalized fields. Acad. Manag. J. 2002, 45, 58–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hotho, S. Professional identity—Product of structure, product of choice: Linking changing professional identity and changing professions. J. Organ. Chang. Manag. 2008, 21, 721–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruess, S.R.; Cruess, R.L.; Steinert, Y. Supporting the development of a professional identity: General principles. Med. Teach. 2019, 41, 641–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Association of Faculties of Pharmacy of Canada. AFPC Educational Outcomes for First Professional Degree Programs in Pharmacy in Canada 2017. Available online: https://www.afpc.info/system/files/public/AFPC-Educational%20Outcomes%202017_final%20Jun2017.pdf (accessed on 14 July 2023).

- Noble, C.; McKauge, L.; Clavarino, A. Pharmacy student professional identity formation: A scoping review. Integr. Pharm. Res. Pract. 2019, 8, 15–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Sullivan, T.A.; Allen, R.A.; Bacci, J.L.; O’Sullivan, A.C. A qualitative study of experiences contributing to professional identity formation in recent pharmacy graduates. Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 2023; 100070, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennie-Kaulbach, N.; Gormley, H.; Davies, H.; Whelan, A.M.; Framp, H.; Price, S.; Janke, K.K. Indicators, influences, and changes in professional identity formation in early experiential learning in community pharmacy. Curr. Pharm. Teach. Learn 2023, 15, 414–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnoldi, J.; Kempland, M.; Newman, K. Assessing student reflections of significant professional identity experiences. Curr. Pharm. Teach. Learn 2022, 14, 1478–1486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Huyssteen, M.; Bheekie, A. The meaning of being a pharmacist: Considering the professional identity development of first-year pharmacy students. Afr. J. Health Prof. Educ. 2015, 7, 208–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moseley, L.E.; McConnell, L.; Garza, K.B.; Ford, C.R. Exploring the evolution of professional identity formation in health professions education. New Dir. Teach. Learn 2021, 2021, 11–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hokanson, K.; Breault, R.R.; Lucas, C.; Charrois, T.L.; Schindel, T.J. Reflective practice: Co-creating reflective activities for pharmacy students. Pharmacy 2022, 10, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shapiro, J.; McMullin, J.; Miotto, G.; Nguyen, T.; Hurria, A.; Nguyen, M.A. Medical students’ creation of original poetry, comics, and masks to explore professional identity formation. J. Med. Humanit. 2021, 42, 603–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aluri, J.; Ker, J.; Marr, B.; Kagan, H.; Stouffer, K.; Yenawine, P.; Kelly-Hedrick, M.; Chisolm, M.S. The role of arts-based curricula in professional identity formation: Results of a qualitative analysis of learner’s written reflections. Med. Educ. Online 2023, 28, 2145105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, M.J. Comics and medicine: Peering into the process of professional identity formation. Acad. Med. 2015, 90, 774–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, E.C.; Carvour, M.L.; Camarata, C.; Andarsio, E.; Rabow, M.W. Requiring the Healer’s Art Curriculum to promote professional identity formation among medical students. J. Med. Humanit. 2020, 41, 531–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephens, M.B.; Bader, K.S.; Myers, K.R.; Walker, M.S.; Varpio, L. Examining professional identity formation through the ancient art of mask-making. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2019, 34, 1113–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarvis-Selinger, S.; Pratt, D.D.; Regehr, G. Competency is not enough: Integrating identity formation into the medical education discourse. Acad. Med. 2012, 87, 1185–1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quinn, G.; Lucas, B.; Silcock, J. Professional identity formation in pharmacy students during an early preregistration training placement. Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 2020, 84, ajpe7804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hickey, E.; DiPiro, J.; Romanelli, F. Prospective health professions students’ misperceptions about pharmacists. Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 2019, 83, 1175–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kellar, J.; Martimianakis, M.A.; Van Der Vleuten, C.P.M.; Oude Egbrink, M.G.A.; Austin, Z. Factors influencing professional identity construction in fourth-year pharmacy students. Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 2023, 87, 415–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morison, S.; O’Boyle, A. Developing professional identity: A study of the perceptions of first year nursing, medical, dental and pharmacy students. In Nursing Education Challenges in the 21st Century; Callara, L.R., Ed.; Nova Science: New York, NY, USA, 2007; pp. 195–220. [Google Scholar]

- Cole, A.L.; Knowles, J.G. Arts-informed research. In Handbook of the Arts in Qualitative Research: Perspectives, Methodologies, Examples, and Issues; Knowles, J.G., Cole, A.L., Eds.; SAGE Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2008; pp. 55–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guillemin, M. Understanding illness: Using drawings as a research method. Qual. Health Res. 2004, 14, 272–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umoquit, M.J.; Tso, P.; Burchett, H.E.D.; Dobrow, M.J. A multidisciplinary systematic review of the use of diagrams as a means of collecting data from research subjects: Application, benefits and recommendations. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2011, 11, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, J.; Ward, K.L. Applying visual research methods in pharmacy education. Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 2020, 84, 95–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, M.M.Y.; Saini, B.; Smith, L. Integrating drawings into health curricula: University educators’ perspectives. Med. Humanit. 2020, 46, 394–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chong, M.; Fitzpatrick, B. Exploring Hidden messages about pharmacist roles in student-designed orientation t-shirts. Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 2022, 86, 706–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- University of Alberta. Doctor of Pharmacy (PharmD). Available online: https://calendar.ualberta.ca/preview_program.php?catoid=34&poid=38931&hl=%22pharmacy%22&returnto=search (accessed on 14 July 2023).

- Faculty of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences, University of Alberta. Doctor of Pharmacy (PharmD) Admission Requirements. Available online: https://www.ualberta.ca/pharmacy/programs/pharmd-doctor-of-pharmacy/admission-requirements.html (accessed on 14 July 2023).

- Canadian Pharmacists Association. Pharmacists’ Scope of Practice in Canada. Available online: https://www.pharmacists.ca/advocacy/scope-of-practice/ (accessed on 14 July 2023).

- Yuksel, N.; Eberhart, G.; Bungard, T.J. Prescribing by pharmacists in Alberta. Am. J. Health-Syst. Pharm. 2008, 65, 2126–2132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safnuk, C.; Ackman, M.L.; Schindel, T.J.; Watson, K.E. The COVID conversations: A content analysis of Canadian pharmacy organizations’ communication of pharmacists’ roles and services during the COVID-19 pandemic. Can. Pharm. J. 2023, 156, 22–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breault, R.R.; Whissell, J.G.; Hughes, C.A.; Schindel, T.J. Development and implementation of the compensation plan for pharmacy services in Alberta, Canada. J. Am. Pharm. Assoc. 2017, 57, 532–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tong, A.; Sainsbury, P.; Craig, J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 2007, 19, 349–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hartel, J.; Noone, R.; Oh, C.; Power, S.; Danzanov, P.; Kelly, B. The iSquare protocol: Combining research, art, and pedagogy through the draw-and-write technique. Qual. Res. 2018, 18, 433–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pridmore, P.; Bendelow, G. Images of health: Exploring beliefs of children using the ‘draw-and-write’ technique. Health Educ. J. 1995, 54, 473–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartel, J. An arts-informed study of information using the draw-and-write technique. J. Assoc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2014, 65, 1349–1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharafizad, F.; Brown, K.; Jogulu, U.; Omari, M. Letting a picture speak a thousand words: Arts-based research in a study of the careers of female academics. Socio. Methods Res. 2023, 52, 438–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schindel, T.J.; Hughes, C.A.; Makhinova, T.; Daniels, J.S. Drawing out experience: Arts-informed qualitative research exploring public perceptions of community pharmacy services. Res. Social. Adm. Pharm. 2022, 18, 2200–2212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potter, J.; Wetherell, M. Discourse and Social Psychology: Beyond Attitudes and Behaviour; SAGE Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1987; p. 216. [Google Scholar]

- Kellar, J.; Paradis, E.; van der Vleuten, C.P.M.; Oude Egbrink, M.G.A.; Austin, Z. A historical discourse analysis of pharmacist identity in pharmacy education. Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 2020, 84, 1251–1258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, M.E.K.; Nørgaard, L.S.; Cavaco, A.M.; Witry, M.J.; Hillman, L.; Cernasev, A.; Desselle, S.P. Establishing trustworthiness and authenticity in qualitative pharmacy research. Res. Social. Adm. Pharm. 2020, 16, 1472–1482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, K.E.; Schindel, T.J.; Chan, J.C.H.; Tsuyuki, R.T.; Al Hamarneh, Y.N. A photovoice study on community pharmacists’ roles and lived experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic. Res. Social. Adm. Pharm. 2023, 19, 944–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santarossa, T.M.; Watson, K.E.; Tsuyuki, R.T. A Twitter analysis of World Pharmacists Day 2020 images: Sending the wrong messages. Can. Pharm. J. 2021, 154, 324–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elvey, R.; Hassell, K.; Hall, J. Who do you think you are? Pharmacists’ perceptions of their professional identity. Int. J. Pharm. Pract. 2013, 21, 322–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jarvis, C.; Gouthro, P. The role of the arts in professional education: Surveying the field. Stud. Educ. Adults. 2015, 47, 64–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisner, E. Art and knowledge. In Handbook of the arts in Qualitative Research: Perspectives, Methodologies, Examples, and Issues; Knowles, J.G., Cole, A.L., Eds.; SAGE Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2008; pp. 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desselle, S.P.; Clubbs, B.H.; Darbishire, P.L. Motivating language and social provisions in the inculcation of pharmacy students’ professional identity. Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 2023, 87, 100010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moniz, T.; Golafshani, M.; Gaspar, C.M.; Adams, N.E.; Haidet, P.; Sukhera, J.; Volpe, R.L.; de Boer, C.; Lingard, L. The prism model: Advancing a theory of practice for arts and humanities in medical education. Perspect. Med. Educ. 2021, 10, 207–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moniz, T.; Golafshani, M.; Gaspar, C.M.; Adams, N.E.; Haidet, P.; Sukhera, J.; Volpe, R.L.; De Boer, C.; Lingard, L. The Prism Model for integrating the arts and humanities into medical education. Acad. Med. 2021, 96, 1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kellar, J.; Lake, J.; Steenhof, N.; Austin, Z. Professional identity in pharmacy: Opportunity, crisis or just another day at work? Can. Pharm. J. 2020, 153, 137–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chien, J.; Axon, D.R.; Cooley, J. Student pharmacists’ perceptions of their professional identity. Curr. Pharm. Teach. Learn 2022, 14, 712–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kellar, J.; Austin, Z. The only way round is through: Professional identity in pharmacy education and practice. Can. Pharm. J. 2022, 155, 238–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Demographics | Participants (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | Female | 59 |

| Male | 39 | |

| Non-binary | 1 | |

| Prefer not to disclose | 1 | |

| Age (years) | <20 | 6 |

| 20–24 | 82 | |

| 25–29 | 11 | |

| 30–34 | 0 | |

| 35–39 | 0 | |

| >40 | 1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Noyen, M.; Sanghera, R.; Kung, J.Y.; Schindel, T.J. Pharmacy Students’ Perceptions of the Pharmacist Role: An Arts-Informed Approach to Professional Identity Formation. Pharmacy 2023, 11, 136. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy11050136

Noyen M, Sanghera R, Kung JY, Schindel TJ. Pharmacy Students’ Perceptions of the Pharmacist Role: An Arts-Informed Approach to Professional Identity Formation. Pharmacy. 2023; 11(5):136. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy11050136

Chicago/Turabian StyleNoyen, Meghan, Ravina Sanghera, Janice Y. Kung, and Theresa J. Schindel. 2023. "Pharmacy Students’ Perceptions of the Pharmacist Role: An Arts-Informed Approach to Professional Identity Formation" Pharmacy 11, no. 5: 136. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy11050136

APA StyleNoyen, M., Sanghera, R., Kung, J. Y., & Schindel, T. J. (2023). Pharmacy Students’ Perceptions of the Pharmacist Role: An Arts-Informed Approach to Professional Identity Formation. Pharmacy, 11(5), 136. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy11050136