How Do European Pharmacy Students Rank Competences for Practice?

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Experimental Section

| The number of students who responded from each country. | |

|---|---|

| Germany | 127 |

| Czech Republic | 32 |

| Portugal | 28 |

| Romania | 21 |

| Belgium | 20 |

| Finland | 18 |

| Macedonia (FYROM) | 12 |

| Croatia | 10 |

| Malta | 10 |

| France | 7 |

| Latvia | 7 |

| Montenegro | 7 |

| Estonia | 6 |

| Greece | 6 |

| Poland | 6 |

| Slovenia | 6 |

| Spain | 6 |

| Norway | 5 |

| The Netherlands | 5 |

| Turkey | 5 |

| UK | 4 |

| Serbia | 3 |

| Switzerland | 3 |

| Austria | 2 |

| Denmark | 2 |

| Sweden | 2 |

| Ukraine | 2 |

| Albania | 1 |

| Bosnia | 1 |

| Hungary | 1 |

| Kosovo | 1 |

| Lithuania | 1 |

| Slovakia | 1 |

| Belarus | 0 |

| Bulgaria | 0 |

| Iceland | 0 |

| Ireland | 0 |

| Italy | 0 |

| Rank | Significance | Explanation |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Not important | Can be ignored |

| 2 | Quite important | Valuable but not obligatory |

| 3 | Very important | Obligatory, with exceptions depending upon field of pharmacy practice |

| 4 | Essential | Obligatory |

- < 0.2 poor,

- 0.21 – 0.4 fair,

- 0.41 – 0.6 moderate,

- 0.61 – 0.8 substantial,

- > 0.81 good.

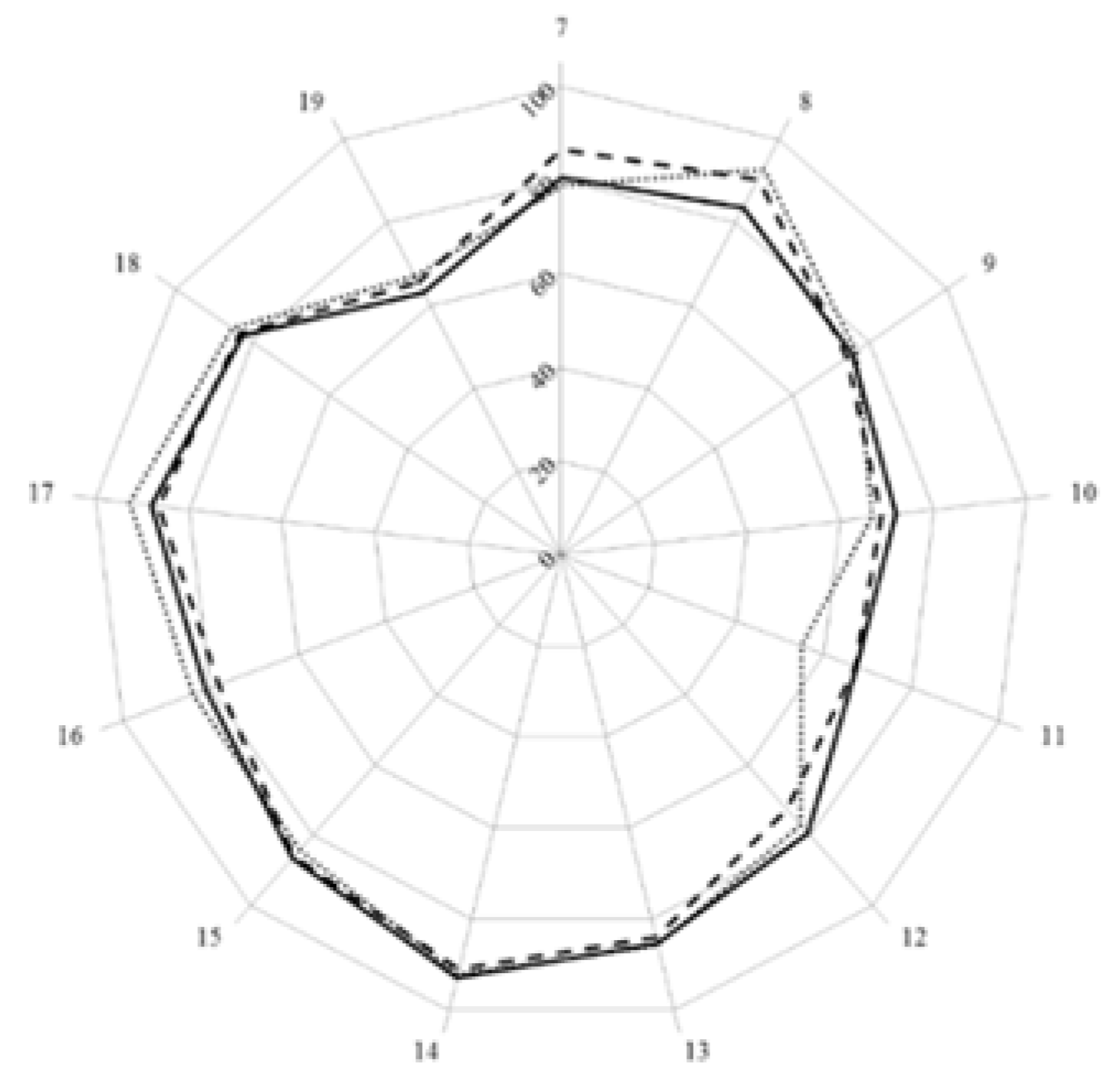

3. Results and Discussion

| Students | Community Pharmacists | Academics | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of respondents | 370 | 258 | 241 | |||

| Theoretical total number of replies | 25,160 (= 370 × 68) | 17,544 (= 258 × 68) | 16,388 (= 241 × 68) | |||

| Replies by rank | Frequency | % | Frequency | % | Frequency | % |

| 4 | 8428 | 33.5 | 6643 | 37.9 | 5821 | 35.5 |

| 3 | 8967 | 35.6 | 6002 | 34.2 | 6005 | 36.6 |

| 2 | 4278 | 17.0 | 3076 | 17.5 | 2982 | 18.2 |

| 1 | 531 | 2.1 | 608 | 3.5 | 366 | 2.2 |

| Cannot rank + blanks | 619 | 11.7 | 1215 | 6.9 | 1214 | 7.4 |

| Score (%) | 77.4 | 78.3 | 77.9 | |||

| Leik ordinal consensus | 0.59 | 0.55 | 0.58 | |||

| Country | Mean Ranking Score (%, n = 68 Competences) | Course Nature | Course Content |

|---|---|---|---|

| Time Spent on Traineeship/Time Spent on Lectures | Time Spent on Medicinal Subjects/Time Spent on Chemical Subjects | ||

| Belgium | 80 | 0.75 | 1.13 |

| Czech Republic | 73 | 0.76 | 1.12 |

| Germany | 78 | 1.25 | 0.71 |

| Portugal | 83 | 0.84 | 1.64 |

| Romania | 84 | 0.66 | 0.95 |

4. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix

| N | Competence | Stud. | Acad. | Chi Stud. vs. Acad. | Comm. | Chi Stud. vs. Comm. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

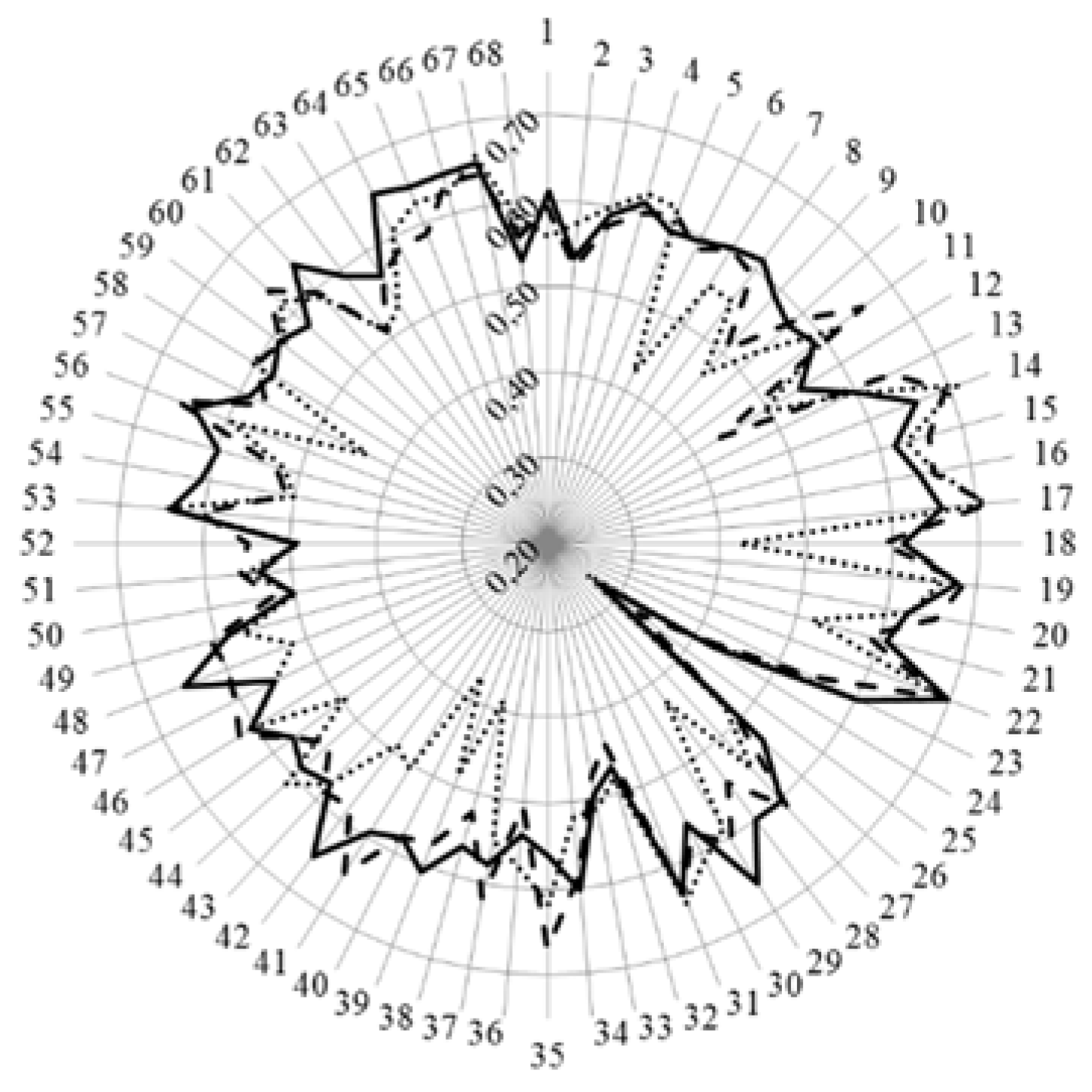

| Cluster 7. Personal competences: learning and knowledge. | 1 | Ability to identify learning needs and to learn independently (including continuous professional development (CPD)). | 84.5 | 93.7 | 15.7 | 89.8 | 13.1 |

| 2 | Analysis: ability to apply logic to problem solving, evaluating pros and cons and following up on the solution found. | 88.8 | 94.5 | 7.5 | 91.1 | 3.6 | |

| 3 | Synthesis: capacity to gather and critically appraise relevant knowledge and to summarise the key points. | 85.1 | 92.8 | 10.8 | 87.9 | 4.0 | |

| 4 | Capacity to evaluate scientific data in line with current scientific and technological knowledge. | 76.5 | 87.3 | 18.5 | 75.8 | 0.4 | |

| 5 | Ability to interpret preclinical and clinical evidence-based medical science and apply the knowledge to pharmaceutical practice. | 86.0 | 81.2 | 5.2 | 75.9 | 17.3 | |

| 6 | Ability to design and conduct research using appropriate methodology. | 60.6 | 65.4 | 4.9 | 40.2 | 34.3 | |

| 7 | Ability to maintain current knowledge of relevant legislation and codes of pharmacy practice. | 81.7 | 86.3 | 3.3 | 91.7 | 25.7 | |

| Cluster 8. Personal competences: values. | 8 | Demonstrate a professional approach to tasks and human relations. | 86.6 | 91.5 | 7.7 | 94.5 | 23.3 |

| 9 | Demonstrate the ability to maintain confidentiality. | 85.4 | 92.3 | 22.8 | 95.3 | 50.6 | |

| 10 | Take full personal responsibility for patient care and other aspects of one’s practice. | 84.4 | 88.3 | 3.2 | 94.8 | 24.9 | |

| 11 | Inspire the confidence of others in one’s actions and advice. | 77.8 | 83.8 | 8.9 | 88.8 | 13.0 | |

| 12 | Demonstrate high ethical standards. | 85.3 | 95.3 | 43.4 | 95.2 | 24.6 | |

| Cluster 9. Personal competences: communication and organisational skills. | 13 | Effective communication skills (both orally and written). | 91.2 | 93.5 | 3.9 | 94.8 | 4.0 |

| 14 | Effective use of information technology. | 81.1 | 83.8 | 1.4 | 86.1 | 3.8 | |

| 15 | Ability to work effectively as part of a tea. | 86.4 | 83.3 | 6.1 | 89.2 | 1.1 | |

| 16 | Ability to identify and implement legal and professional requirements relating to employment (e.g., for pharmacy technicians) and to safety in the workplace. | 74.8 | 77.9 | 1.9 | 81.0 | 4.5 | |

| 17 | Ability to contribute to the learning and training of staff. | 73.5 | 79.6 | 6.6 | 82.5 | 6.6 | |

| 18 | Ability to design and manage the development processes in the production of medicines. | 61.2 | 60.0 | 0.8 | 43.2 | 38.0 | |

| 19 | Ability to identify and manage risk and quality of service issues. | 77.5 | 76.1 | 4.0 | 79.2 | 2.3 | |

| 20 | Ability to identify the need for new services. | 65.0 | 61.8 | 7.7 | 64.5 | 1.2 | |

| 21 | Ability to communicate in English and/or locally relevant languages. | 84.5 | 79.6 | 2.3 | 74.1 | 16.3 | |

| 22 | Ability to evaluate issues related to quality of service. | 73.0 | 71.0 | 3.5 | 77.9 | 7.4 | |

| 23 | Ability to negotiate, understand a business environment and develop entrepreneurship. | 62.2 | 46.4 | 15.6 | 64.1 | 2.0 | |

| Cluster 10. Personal competences: knowledge of different areas of the science of medicines. | 24 | Plant and animal biology. | 38.8 | 31.1 | 5.1 | 39.3 | 1.0 |

| 25 | Physics. | 20.9 | 25.6 | 2.3 | 21.7 | 0.8 | |

| 26 | General and inorganic chemistry | 53.0 | 45.6 | 3.3 | 43.9 | 5.3 | |

| 27 | Organic and medicinal/pharmaceutical chemistry. | 86.3 | 80.2 | 10.8 | 66.0 | 37.0 | |

| 28 | Analytical chemistry | 65.8 | 60.0 | 3.0 | 41.9 | 46.9 | |

| 29 | General and applied biochemistry (medicinal and clinical). | 85.4 | 74.2 | 10.8 | 68.8 | 22.6 | |

| 30 | Anatomy and physiology; medical terminology. | 85.2 | 75.8 | 11.2 | 88.7 | 3.3 | |

| 31 | Microbiology. | 72.2 | 67.0 | 3.3 | 72.2 | 1.5 | |

| 32 | Pharmacology including pharmacokinetics. | 97.5 | 95.6 | 3.7 | 94.7 | 3.0 | |

| 33 | Pharmacotherapy and pharmaco-epidemiology. | 95.3 | 92.5 | 3.1 | 94.3 | 2.2 | |

| 34 | Pharmaceutical technology including analyses of medicinal products. | 86.9 | 89.0 | 1.4 | 62.0 | 50.8 | |

| 35 | Toxicology. | 85.0 | 84.4 | 17.3 | 74.0 | 27.7 | |

| 36 | Pharmacognosy. | 65.9 | 52.9 | 11.3 | 66.5 | 2.1 | |

| 37 | Legislation and professional ethics. | 71.7 | 88.8 | 26.8 | 89.5 | 44.2 | |

| Cluster 11. Personal competences: understanding of industrial pharmacy. | 38 | Current knowledge of design, synthesis, isolation, characterisation and biological evaluation of active substances. | 59.9 | 57.5 | 1.9 | 41.7 | 34.2 |

| 39 | Current knowledge of good manufacturing practice (GMP) and of good laboratory practice (GLP). | 79.2 | 75.4 | 1.6 | 59.4 | 29.8 | |

| 40 | Current knowledge of European directives on qualified persons (QPs). | 55.3 | 59.2 | 1.8 | 43.7 | 39.9 | |

| 41 | Current knowledge of drug registration, licensing and marketing. | 65.7 | 72.1 | 4.6 | 55.7 | 11.9 | |

| 42 | Current knowledge of good clinical practice (GCP). | 78.1 | 68.2 | 9.1 | 64.5 | 23.8 | |

| Cluster 12. Patient care competences: patient consultation and assessment. | 43 | Ability to perform and interpret medical laboratory tests. | 72.0 | 65.3 | 5.9 | 65.5 | 6.0 |

| 44 | Ability to perform appropriate diagnostic or physiological tests to inform clinical decision making e.g., measurement of blood pressure. | 76.1 | 64.5 | 17.3 | 73.6 | 7.8 | |

| 45 | Ability to recognise when referral to another member of the healthcare team is needed because a potential clinical problem is identified (pharmaceutical, medical, psychological or social). | 91.7 | 89.1 | 2.2 | 91.7 | 9.5 | |

| Cluster 13. Patient care competences: need for drug treatment. | 46 | Retrieval and interpretation of relevant information on the patient’s clinical background. | 85.6 | 79.3 | 8.4 | 84.0 | 0.7 |

| 47 | Retrieval and interpretation of an accurate and comprehensive drug history if and when required. | 87.6 | 89.4 | 5.1 | 91.5 | 2.3 | |

| 48 | Identification of non-adherence and implementation of appropriate patient intervention. | 87.1 | 85.8 | 6.1 | 86.8 | 24.5 | |

| 49 | Ability to advise to physicians and—in some cases—prescribe medication. | 81.9 | 80.7 | 2.5 | 87.6 | 5.3 | |

| Cluster 14. Patient care competences: drug interactions. | 50 | Identification, understanding and prioritisation of drug-drug interactions at a molecular level (e.g., use of codeine with paracetamol). | 91.4 | 91.8 | 1.1 | 91.6 | 0.6 |

| 51 | Identification, understanding, and prioritisation of drug-patient interactions, including those that preclude or require the use of a specific drug (e.g., trastuzumab for treatment of breast cancer in women with HER2 overexpression). | 91.4 | 87.7 | 4.4 | 89.7 | 5.0 | |

| 52 | Identification, understanding, and prioritisation of drug-disease interactions (e.g., NSAIDs in heart failure). | 97.0 | 94.5 | 8.9 | 96.6 | 2.7 | |

| Cluster 15. Patient care competences: provision of drug product. | 53 | Familiarity with the bio-pharmaceutical, pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic activity of a substance in the body. | 89.3 | 90.8 | 3.5 | 81.2 | 11.6 |

| 54 | Supply of appropriate medicines taking into account dose, correct formulation, concentration, administration route and timing. | 94.3 | 96.3 | 16.3 | 94.9 | 18.0 | |

| 55 | Critical evaluation of the prescription to ensure that it is clinically appropriate and legal. | 93.9 | 94.1 | 6.6 | 94.0 | 11.1 | |

| 56 | Familiarity with the supply chain of medicines and the ability to ensure timely flow of drug products to the patient. | 81.6 | 78.6 | 4.5 | 84.6 | 11.3 | |

| 57 | Ability to manufacture medicinal products that are not commercially available. | 74.1 | 69.0 | 1.5 | 60.5 | 21.2 | |

| Cluster 16. Patient care competences: patient education. | 58 | Promotion of public health in collaboration with other actors in the healthcare system. | 75.8 | 75.1 | 1.1 | 82.6 | 5.9 |

| 59 | Provision of appropriate lifestyle advice on smoking, obesity, etc. | 76.9 | 71.0 | 3.8 | 80.9 | 4.7 | |

| 60 | Provision of appropriate advice on resistance to antibiotics and similar public health issues. | 90.3 | 89.4 | 5.2 | 93.1 | 3.6 | |

| Cluster 17. Patient care competences: provision of information and service. | 61 | Ability to use effective consultations to identify the patient’s need for information. | 85.6 | 81.1 | 3.1 | 90.9 | 11.1 |

| 62 | Provision of accurate and appropriate information on prescription medicines. | 92.7 | 89.3 | 8.0 | 94.4 | 11.0 | |

| 63 | Provision of informed support for patients in selection and use of non-prescription medicines for minor ailments (e.g., cough remedies). | 85.7 | 89.4 | 1.7 | 94.0 | 14.4 | |

| Cluster 18. Patient care competences: monitoring of drug therapy. | 64 | Identification and prioritisation of problems in the management of medicines in a timely manner and with sufficient efficacy to ensure patient safety. | 88.5 | 87.9 | 8.2 | 93.0 | 8.7 |

| 65 | Ability to monitor and report to all concerned in a timely manner, and in accordance with current regulatory guidelines on Good Pharmacovigilance Practices (GVPs), Adverse Drug Events and Reactions (ADEs and ADRs). | 79.8 | 80.9 | 5.0 | 83.4 | 3.3 | |

| 66 | Undertaking of a critical evaluation of prescribed medicines to confirm that current clinical guidelines are appropriately applied. | 80.7 | 81.6 | 0.3 | 80.6 | 4.5 | |

| Cluster 19. Patient care competences: evaluation of outcomes. | 67 | Assessment of outcomes on the monitoring of patient care and follow-up interventions. | 73.3 | 73.7 | 0.5 | 79.0 | 4.4 |

| 68 | Evaluation of cost effectiveness of treatment. | 53.3 | 57.7 | 2.1 | 61.2 | 4.8 |

References

- The PHARMINE (Pharmacy Education in Europe) consortium. Work programme 3: Final Report Identifying and Defining Competences for Pharmacists. Available online: http://www.pharmine.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/05/PHARMINE-WP3-Final-ReportDEF_LO.pdf (accessed on 12 January 2016).

- Rutter, V.; Wong, C.; Coombes, I.; Cardiff, L.; Duggan, C.; Yee, M.L.; Lim, K.W.; Bates, I. Use of a General Level Framework to Facilitate Performance Improvement in Hospital Pharmacists in Singapore. Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 2012, 76, 1–10. Available online: http://www.ajpe.org/action/doSearch?AllField=bates (accessed on 12 January 2016). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coombes, I.; Avent, M.; Cardiff, L.; Bettenay, K.; Coombes, J.; Whitfield, K.; Stokes, J.; Davies, G.; Bates, I. Improvement in Pharmacist’s Performance Facilitated by an Adapted Competency-Based General Level Framework. J. Pharm. Pract. Res. 2010, 40, 111–118. Available online: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/j.2055–2335.2010.tb00517.x/abstract (accessed on 12 January 2016). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antoniou, S.; Webb, D.G.; Mcrobbie, D.; Davies, J.G.; Bates, I.P. A controlled study of the general level framework: Results of the South of England competency study. Pharm. Educ. 2005, 5, 1–8. Available online: http://pharmacyeducation.fip.org/pharmacyeducation/article/view/171/146 (accessed on 12 January 2016). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winslade, N.E.; Tamblyn, R.M.; Taylor, L.K.; Schuwirth, L.W.T.; Van der Vleuten, C.P.M. Integrating Performance Assessment, Maintenance of Competence, and Continuing Professional Development of Community Pharmacists. In Am. J. Pharm. Educ.; 2007; 71, pp. 1–9. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/journals/383/ (accessed on 12 January 2016). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The PHAR-QA Project. Quality Assurance in European Pharmacy Education and Training. Available online: www.phar-qa.eu (accessed on 12 January 2016).

- Medical Education in Europe. Available online: http://medine2.com/ (accessed on 12 January 2016).

- The Survey Software—The Survey System. Available online: http://www.surveysystem.com/sscalc.htm (accessed on 12 January 2016).

- Atkinson, J.; de Paepe, K.; Sánchez Pozo, A.; Rekkas, D.; Volmer, D.; Hirvonen, J.; Bozic, B.; Skowron, A.; Mircioiu, C.; Marcincal, A.; et al. The PHAR-QA Project: Competency Framework for Pharmacy Practice—First Steps, the Results of the European Network Delphi Round 1. Pharmacy 2015, 3, 307–329. Available online: https://www.mdpi.com/2226-4787/3/4/307 (accessed on 12 January 2016). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The European Higher Education Area. Available online: http://www.ehea.info/ (accessed on 12 January 2016).

- Marz, R.; Dekker, F.W.; Van Schravendijk, C.; O’Flynn, S.; Ross, M.T. Tuning research competences for Bologna three cycles in medicine: Report of a MEDINE2 European Consensus Survey. In Perp. Med. Educ.; 2013; 2, pp. 181–195. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3792236/ (accessed on 12 January 2016). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leik, R.K. A measure of ordinal consensus. Pac. Soc. Rev. 1966, 9, 85–90. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1388242 (accessed on 12 January 2016). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkinson, J. Heterogeneity of Pharmacy Education in Europe. Pharmacy 2014, 2, 231–243. Available online: https://www.mdpi.com/search?q=&journal=pharmacy&volume=&page=&authors=atkinson§ion=&issue=&number=&article_type=&special_issue=&search=Search (accessed on 12 January 2016). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chambers, J.; Cleveland, W.; Kleiner, B.; Tukey, P. Graphical Methods for Data Analysis. J. Appl. Stat. 1984, 11, 233–234. Available online: http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/02664768400000024?journalCode=cjas20#.VciiCocbCpo (accessed on 12 January 2016). [Google Scholar]

- The GraphPad Statistical Pack. Available online: http://www.graphpad.com/ (accessed on 12 January 2016).

- Van Schravendijk, C.; Marz, R.; Garcia-Sloane, J. Exploring the integration of the biomedical research component in undergraduate medical education. Med. Teach. 2013, 35, e1243–e1251. Available online: http://informahealthcare.com/doi/pdfplus/10.3109/0142159X.2013.768337 (accessed on 12 January 2016). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bruno, A.; Bates, I.; Brock, T.; Anderson, C. Towards a Global Competency Framework. In Am. J. Pharm. Educ.; 2010; 74, pp. 1–2. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2865424/ (accessed on 12 January 2016). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Erasmus+. EU Programme for Education, Training, Youth and Sport. Available online: http://ec.europa.eu/programmes/erasmus-plus/index_en.htm (accessed on 12 January 2016).

- TOEFL—Test of English as a Foreign Language. Available online: http://www.ets.org/toefl (accessed on 12 January 2016).

- Fernandez, N.; Dory, V.; Ste-Marie, L.G.; Chaput, M.; Charlin, B.; Boucher, A. Varying conceptions of competence: An Analysis of how Health Sciences Educators Define Competence. Med. Educ. 2012, 46, 357–365. Available online: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1365–2923.2011.04183.x/abstract (accessed on 12 January 2016). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The EU Directive 2013/55/EU on the Recognition of Professional Qualifications. Available online: http://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=OJ:L:2005:255:0022:0142:EN:PDF (accessed on 12 January 2016).

- Miller, G.E. The assessment of clinical skills/competences/performance. Acad. Med. 1990, 65, 63–67. Available online: http://winbev.pbworks.com/f/Assessment.pdf (accessed on 26 January 2016). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carr, S.J. Assessing clinical competency in medical senior house officers: How and Why Should We Do it? Postgrad. Med. J. 2004, 80, 63–66. Available online: http://pmj.bmj.com/content/80/940/63.full.pdf+html. (accessed on 12 January 2016). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

© 2016 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons by Attribution (CC-BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Atkinson, J.; De Paepe, K.; Sánchez Pozo, A.; Rekkas, D.; Volmer, D.; Hirvonen, J.; Bozic, B.; Skowron, A.; Mircioiu, C.; Marcincal, A.; et al. How Do European Pharmacy Students Rank Competences for Practice? Pharmacy 2016, 4, 8. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy4010008

Atkinson J, De Paepe K, Sánchez Pozo A, Rekkas D, Volmer D, Hirvonen J, Bozic B, Skowron A, Mircioiu C, Marcincal A, et al. How Do European Pharmacy Students Rank Competences for Practice? Pharmacy. 2016; 4(1):8. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy4010008

Chicago/Turabian StyleAtkinson, Jeffrey, Kristien De Paepe, Antonio Sánchez Pozo, Dimitrios Rekkas, Daisy Volmer, Jouni Hirvonen, Borut Bozic, Agnieska Skowron, Constantin Mircioiu, Annie Marcincal, and et al. 2016. "How Do European Pharmacy Students Rank Competences for Practice?" Pharmacy 4, no. 1: 8. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy4010008

APA StyleAtkinson, J., De Paepe, K., Sánchez Pozo, A., Rekkas, D., Volmer, D., Hirvonen, J., Bozic, B., Skowron, A., Mircioiu, C., Marcincal, A., Koster, A., Wilson, K., Van Schravendijk, C., & Hočevar, S. (2016). How Do European Pharmacy Students Rank Competences for Practice? Pharmacy, 4(1), 8. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy4010008