Perceptions of Pharmacy Involvement in Social Prescribing Pathways in England, Scotland and Wales

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- (1)

- Explore the pharmacy team’s knowledge of social prescribing as a concept,

- (2)

- Identify the pharmacy team’s awareness or experiences of local schemes

- (3)

- Explore participant views on ways the pharmacy team can be involved,

- (4)

- Identify barriers and enablers to the pharmacy team involvement.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethics

2.2. Sampling and Recruitment

2.3. Data Collection and Analysis

3. Results

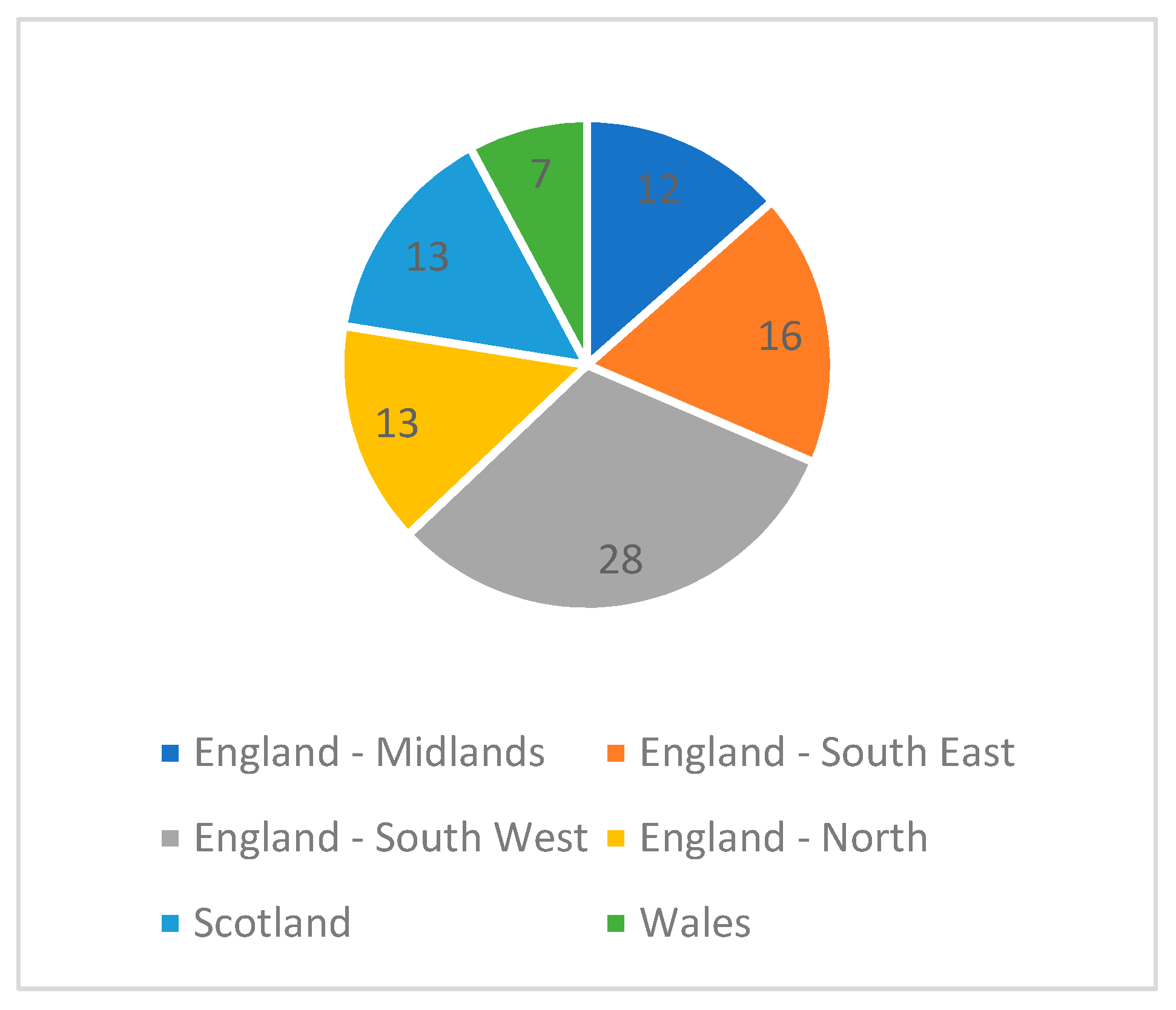

3.1. Demographics

3.2. Prior Knowledge and/or Experience of Social Prescribing

- treatment without the use of medication (n = 15);

- treatment that is non-clinical or non-medical (n = 12);

- exercise on prescription/lifestyle changes (n = 4);

- a way of linking patients to services in the community to improve health, wellbeing, and/or social interaction (n = 4);

- treatment specialised for a specific need e.g., social isolation/increasing activity (n = 3);

- a way to refer patients to groups/organisations that provide social care (n = 3);

- emergency (A&E) attendance (n = 1); and 2 were not sure, but had heard the term before.

“My understanding is where (social) prescribing is for non-medicinal strategies, for example wellbeing, CBT, dietary, exercise, support.”Respondent 23 (Pharmacist)

“Physical activity rather than a pill for every ill.”Respondent 45 (Pharmacist)

3.3. The Appropriateness of the Name “Social Prescribing”

- Wellbeing intervention;

- Social activity programme;

- Social wellbeing scheme/programme;

- Wellbeing referral or wellbeing activity referral;

- Social activity prescribing;

- Health and wellbeing pathways.

3.4. Beliefs about Social Prescribing

3.5. Who Should Be Involved?

“HCP qualifications do not seem necessarily required for this type of intervention, it should be expanded to other people too, as then it has more likelihood of succeeding and being managed through larger networks.”Participant 13 (Pharmacist)

“Any person should be able to refer a needy patient for help.”Participant 76 (Pharmacy Technician)

“Some vulnerable people may not come into contact with healthcare professionals on a regular basis; however there may be others in the community with whom they have contact.”Participant 37 (Pharmacist)

3.5.1. Pharmacist Involvement in Social Prescribing

“We can get to know patients over consultations for different care aspects, and may come to realise that drugs are not always the most appropriate therapy. As HCPs we should be signposting for all aspects of healthy lifestyle changes.”Participant 90, Pharmacist

“Pharmacists are there to clinically check/provide/counsel patients on medicines. Although a nice idea (and something other healthcare professionals/volunteers are suitable placed to encourage/advise patients on this), this activity is not in the pharmacist remit.”Participant 24, Pharmacist

3.5.2. Pharmacy Team Involvement

“Suitably trained technicians would be just as capable in providing this service, in some respects they may well be better placed to do so, to free up the pharmacists time for clinical roles.”Participant 1, Pharmacy Technician

3.6. Pharmacy Involvement in SP Services

3.7. Barriers and Enablers

- (1)

- the need for SP in the local community (78.9%, n = 75)

- (2)

- pharmacist skill in identifying potential individuals’ for SP (73.7%, n = 70)

- (3)

- pharmacist desire to be involved in SP (70.6%, n = 67)

- (4)

- evidence for the benefit of SP (67.4%, n + 64)

- (5)

- availability of a consultation room (66.3%, n = 63)

3.8. Pharmacy Confidence in Being Part of a Social Prescribing Pathway

3.9. Training

4. Discussion

4.1. Limitations

4.2. Implications for Including Pharmacy in Social Prescribing Pathways

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pickett, K.; Melhuish, E.; Dorling, D.; Bambra, C.; McKenzie, K.; Chandda, T.; Jenkins, A.; Nazroo, J.; Maynard, A. If You Could Do One Thing: Nine Local Actions to Reduce Health Inequalities; The British Academy: London, UK, 2014; ISBN 978-0-85672-611-8. Available online: https://www.thebritishacademy.ac.uk/publications/if-you-could-do-one-thing (accessed on 24 February 2019).

- Kimberlee, R. Developing A Social Prescribing Approach for Bristol; Project Report; Bristol Health & Wellbeing Board: Bristol, UK, 2013; Available online: http://eprints.uwe.ac.uk/23221 (accessed on 24 February 2019).

- Caper, K.; Plunkett, J. A Very General Practice: How Much Time Do GPs Spend on Issues Other Than Health? Citizen’s Advice Bureau: London, UK, 2015; Available online: https://www.citizensadvice.org.uk/Global/CitizensAdvice/Public%20services%20publications/CitizensAdvice_AVeryGeneralPractice_May2015.pdf (accessed on 24 February 2019).

- Steadman, K.; Thomas, R.; Donnaloja, V. Social Prescribing: A Pathway to Work? London, UK, 2017. Available online: http://www.theworkfoundation.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/412_Social_prescribing.pdf (accessed on 24 February 2019).

- Brandling, J.; House, W. Social prescribing in general practice: Adding meaning to medicine. Br. J. Gen. Pract. 2009, 59, 454–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moffatt, S.; Steer, M.; Lawson, S.; Penn, L.; O’Brien, N. Link worker social prescribing to improve health and well-being for people with long-term conditions: Qualitative study of service user perceptions. BMJ Open 2017, 7, e015203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Langford, K.; Baeck, P.; Hampson, M. More Than Medicine-New Services for People Powered Health; London, UK, 2013. Available online: https://media.nesta.org.uk/documents/more_than_medicine.pdf (accessed on 24 February 2019).

- Kimberlee, R.; Polley, M.; Bertotti, M.; Pilkington, K.; Refsum, C. A Review of the Evidence Assessing Impact of Social Prescribing on Healthcare Demand and Cost Implications; University of Westminster: London, UK, 2017; Available online: https://westminsterresearch.westminster.ac.uk/item/q1455/a-review-of-the-evidence-assessing-impact-of-social-prescribing-on-healthcare-demand-and-cost-implications (accessed on 24 February 2019).

- Bickerdike, L.; Booth, A.; Wilson, P.M.; Farley, K.; Wright, K. Social prescribing: Less rhetoric and more reality. A systematic review of the evidence. BMJ Open 2017, 7, e013384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Local Government Association. Just What Doctor Ordered: Social Prescribing—A Guide for Local Authorities; London, UK, 2016. Available online: https://www.local.gov.uk/just-what-doctor-ordered-social-prescribing-guide-local-authorities (accessed on 24 February 2019).

- Anon, Statista, the Statistics Portal. Annual Number of Pharmacists in the United Kingdom (UK) from 2010 to 2018 (in 1000). Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/318874/numbers-of-pharmacists-in-the-uk/ (accessed on 24 February 2019).

- Robinson, S. RPS membership grows for second consecutive year. Pharm J. 2015, 294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, M. Pharmacist with a portfolio career. Pharm J. 2008, 280, 580. Available online: https://www.pharmaceutical-journal.com/careers-and-jobs/careers-and-jobs/career-feature/pharmacist-with-a-portfolio-career/10004390.article (accessed on 25 February 2019).

- Brown, D.; Portlock, J.; Rutter, P.; Nazar, Z. From community pharmacy to healthy living pharmacy: Positive early experiences from Portsmouth, England. Res. Soc. Adm. Pharm. 2014, 10, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anon; Pharmaceutical Services Negotiating Committee. Healthy Living Pharmacies. Available online: http://psnc.org.uk/services-commissioning/locally-commissioned-services/healthy-living-pharmacies/ (accessed on 24 February 2019).

- Carnes, D.; Sohanpal, R.; Matthur, R.; Homer, K.; Hull, S.; Bertotti, B.; Frostick, C.; Netuveli, G.; Tong, J.; Findlay, G.; et al. City and Hackney Social Prescribing Service: Evaluation Report; Queen Mary University of London, Barts Health, The London School of Medicine and Dentistry and University East London: London, UK, November 2015. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Marcello_Bertotti/publication/286354138_City_and_Hackney_Social_Prescribing_Service_Evaluation_Report/links/5667fd5008ae8905db8c5102/City-and-Hackney-Social-Prescribing-Service-Evaluation-Report.pdf (accessed on 24 February 2019).

- Dayson, C.; Bashir, N. The Social and Economic Impact of the Rotherham Social Prescribing Pilot: Main Evaluation Report; Sheffield Hallam University, Centre for Regional Economic and Social Research: Sheffield, UK, 2014; Available online: https://www4.shu.ac.uk/research/cresr/sites/shu.ac.uk/files/social-economic-impact-rotherham.pdf (accessed on 24 February 2019).

- Dayson, C.; Bennett, E. Evaluation of Doncaster Social Prescribing Service: Understanding Outcomes and Impact; Sheffield Hallam University, Centre for Regional Economic and Social Research: Sheffield, UK, 2016; Available online: https://www4.shu.ac.uk/research/cresr/sites/shu.ac.uk/files/eval-doncaster-social-prescribing-service.pdf (accessed on 24 February 2019).

- HM Government. A Connected Society. A Strategy for Tackling Loneliness–Laying the Foundations for Change. Available online: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/750909/6.4882_DCMS_Loneliness_Strategy_web_Update.pdf (accessed on 24 February 2019).

| Age (Years) | Respondents n = (%) |

|---|---|

| 20–25 | • 5 (5.4) |

| 26–35 | • 25 (26.9) |

| 36–45 | • 25 (26.9) |

| 46–55 | • 17 (18.3) |

| >56 | • 21 (22.5) |

| Total (n=) | • 93 (100%) |

| Years Qualified | Respondents n = (%) |

|---|---|

| 0–5 | • 14 (15.1) |

| 6–10 | • 15 (16.1) |

| 11–15 | • 16 (17.2) |

| 16–20 | • 7 (7.5) |

| >21 | • 41 (44.1) |

| Total (n=) | • 93 (100%) |

| Sector | Respondents |

|---|---|

| Hospital | • 37 |

| Primary Care | • 23 |

| Community health provider | • 1 |

| Community pharmacy | • 36 |

| Retired/not working | • 3 |

| Industry | • 2 |

| Prison | • 1 |

| Health policy | • 4 |

| Academia and education | • 4 |

| Total (n=) | • 112 |

| Respondent Activity/Role | Social Prescribing Pathway |

|---|---|

| Supporting local schemes |

|

| Specialist services |

|

| Referral |

|

| Prescribing |

|

| Alternative Name Suggestion | Respondents n =(%) |

|---|---|

| Social activity pathway | • 28 (40.6) |

| Community referrals | • 17 (24.6) |

| Social referral programme | • 14 (20.3) |

| Social intervention | • 2 (2.9) |

| Other | • 8 (11.6) |

| Total (n=) | • 69 (100%) |

| Belief | Agree or Strongly Agree n = (%) | Neither Agree or Disagree n = (%) | Disagree or Strongly Disagree n = (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| I believe social prescribing could be a valid approach to healthcare | 107 (96.4) | 3 (2.70) | 1 (0.90) |

| I believe social prescribing could address the social and emotional needs of those who take part. | 105 (94.6) | 6 (5.41) | 0 |

| I believe social prescribing could benefit individuals who take part in it. | 109 (98.2) | 2 (1.80) | 0 |

| I believe pharmacy and pharmacists could have a role in social prescribing. | 95 (85.6) | 13 (11.7) | 3 (2.70) |

| I believe pharmacist involvement in social prescribing could benefit the individuals who take part | 93 (83.8) | 15 (13.51) | 3 (2.70) |

| Acceptable Level of Involvement | Respondents (n =) |

|---|---|

| Identifying individuals suitable for SP | • 75 |

| Delivering a pharmacy related SP service as appropriate | • 51 |

| Introducing the concept of SP & referring to the SP coordinator | • 48 |

| Monitoring the individual in their engagement with SP activities | • 31 |

| Introducing the concept of SP to an individual and referring to GP | • 29 |

| Being a SP coordinator and after completing a needs assessment, agreeing a SP plan | • 29 |

| Other | • 14 |

| I am not willing to be involved | • 4 |

| Barriers/Enablers | Strong Enabler n = (%) | Enabler n = (%) | Neither Enabler or Barrier n = (%) | Barrier n = (%) | Strong Barrier n = (%) | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Available space for consultation | 30 (31.6) | 33 (34.7) | 16 (16.8) | 15 (15.8) | 1 (1.1) | 95 |

| Funding available | 32 (33.7) | 12 (12.6) | 13 (13.7) | 25 (26.3) | 13 (13.7) | 95 |

| Pharmacist skill in detecting those that may benefit from SP | 26 (27.4) | 44 (46.3) | 16 (16.8) | 7 (7.4) | 2 (2.1) | 95 |

| Need within the community for SP | 35 (36.8) | 40 (42.1) | 17 (17.9) | 2 (2.1) | 1 (1.1) | 95 |

| Pharmacist desire to be involved in SP | 26 (27.4) | 41 (43.2) | 13 (13.7) | 14 (14.7) | 1 (1.1) | 95 |

| Evidence of the benefit of SP | 19 (20.0) | 45 (47.4) | 20 (21.1) | 7 (7.4) | 4 (4.2) | 95 |

| Available time for more consultations | 27 (28.4) | 13 (13.7) | 9 (9.5) | 34 (35.8) | 12 (12.6) | 95 |

| Knowledge of current local SP pathways | 28 (29.5) | 22 (23.2) | 14 (14.7) | 26 (27.4) | 5 (5.3) | 95 |

| Employment cost of pharmacists | 12 (12.6) | 15 (15.8) | 22 (23.2) | 33 (34.7) | 13 (13.7) | 95 |

| Skill set of wider pharmacy team | 18 (19.0) | 35 (36.8) | 19 (20.0) | 19 (20.0) | 4 (4.2) | 95 |

| Enablers | Barriers |

|---|---|

| Funding | Funding/lack of sustainability |

| Time | Time |

| Knowledge of scheme | Lack of knowledge of schemes |

| Expertise | Lack of expertise |

| Regular contact with patients | Variation in patients |

| Perceived need by commissioners | Lack of support from senior members of staff |

| Collaborative working | Collaborative working with GP’s and activity |

| The pharmacy being seen as a respected voice and being easily accessible | Providers—particularly confidentiality |

| Non-pharmacist managers | |

| Lack of confidence |

| Services | Responses n = |

|---|---|

| Weight management | 4 |

| Exercise | 3 |

| Smoking cessation | 1 |

| Patient champion and referral | 1 |

| Cancer services | 1 |

| Other services | 1 |

| Training Need | Responses n= |

|---|---|

| What activities are available | 83 |

| Inclusion criteria for activities | 81 |

| Understanding more about social prescribing | 72 |

| Pharmacist roles in social prescribing | 67 |

| Condition specific information such as signs and symptoms | 61 |

| Communication skills | 25 |

| Other | 7 |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Taylor, D.A.; Nicholls, G.M.; Taylor, A.D.J. Perceptions of Pharmacy Involvement in Social Prescribing Pathways in England, Scotland and Wales. Pharmacy 2019, 7, 24. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy7010024

Taylor DA, Nicholls GM, Taylor ADJ. Perceptions of Pharmacy Involvement in Social Prescribing Pathways in England, Scotland and Wales. Pharmacy. 2019; 7(1):24. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy7010024

Chicago/Turabian StyleTaylor, Denise A., Gina M. Nicholls, and Andrea D.J. Taylor. 2019. "Perceptions of Pharmacy Involvement in Social Prescribing Pathways in England, Scotland and Wales" Pharmacy 7, no. 1: 24. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy7010024

APA StyleTaylor, D. A., Nicholls, G. M., & Taylor, A. D. J. (2019). Perceptions of Pharmacy Involvement in Social Prescribing Pathways in England, Scotland and Wales. Pharmacy, 7(1), 24. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy7010024