2.1. Pharmacist Training and Practice Support

AKPhA and the SETMuPP team partnered with the DHSS’s Diabetes, Heart Disease, and Stroke Prevention Program to conduct focus groups and semistructured interviews to identify barriers related to coding, billing, and reimbursement for services provided by outpatient pharmacists. Three high-level themes believed to impact the uptake of nondispensing pharmacist services were identified in the qualitative data: training needs, resource needs, and system implementation needs. Gaps in knowledge regarding existing and potential nondispensing pharmacist services were noted among all three stakeholder groups. Most were unaware of the different types of services pharmacists are capable of providing, the extensive training pharmacists have, and the potential cost-savings associated with pharmacist-provided health services (e.g., immunizations). These results were used to develop and conduct a statewide pharmacist survey to identify and better quantify the barriers that pharmacists face when providing diabetes and cardiovascular disease prevention and management services. The questions referred to the number and type of direct pharmacist-provided health services distinct from traditional prescription dispensing functions, the capacity to provide services, and the barriers to the provision of service. The services of interest included, but were not limited to, medication therapy management (MTM), collaborative drug therapy management (CDTM), specialized patient education and counseling (e.g., diabetes), immunizations, point-of-care testing, and those currently being provided. Finally, a SOAR (strengths, opportunities, aspirations, and results) analysis was completed. The results of our preliminary analyses suggested that pharmacists not only could benefit from additional training in coding and billing the medical benefit or nondispensing services, but also that additional legislative, regulatory, and technology supports could better facilitate the expansion of pharmacist-provided nondispensing services, especially in rural and underserved communities. These findings provided a framework to identify training needs that were used to develop a draft toolkit and training program. The goals of the toolkit and training program are to promote existing medical billing best practices and translate them to a pharmacy audience. The toolkit consists of established billing and reimbursement materials/resources utilized by all other health disciplines (e.g., credentialing and privileging process guidance, site-assessment checklists, contract drafts, collaborative practice agreements, billing forms, hands-on exercises for pharmacists to practice coding and billing encounters, and audit processes).

This toolkit, along with SETMuPP-delivered training, served as the basis to educate staff at two primary care pilot sites, establishing a shared vernacular and understanding of service reimbursement process, and promoted “buy-in” from health system administrators. The toolkit and training were also more widely disseminated at a one-day AKPhA-sponsored program focused on medical billing for pharmacists. To assess the impact of the pilot project implementation and toolkit, SETMuPP team members routinely connected with the pharmacists at the pilot sites. Claim submissions and rejections were collected to identify and respond to additional training and support needs. Based on the experience at the initial pilot site, we identified breaks in the claim submission process and tailored workflows to address these communication and information sharing breakdowns. These lessons were used to develop a second iteration of the toolkit/training for the second pilot site, a Federally Qualified Health Center (FQHC). SETMuPP team members also created and deployed a patient satisfaction survey to assess community interest at the initial pilot site. Patient satisfaction scores were overwhelmingly positive, with a majority of patients expressing a high value of the services they received (publication pending).

Services potentially eligible for billing under the medical benefit were delivered by both pilot sites. Claims were generated and submitted according to the usual practices at the site, thus site-specific billing personnel were responsible for claim submission and tracking. Service data was submitted by both pilot sites to the SETMuPP team to measure the quantity and type of services delivered.

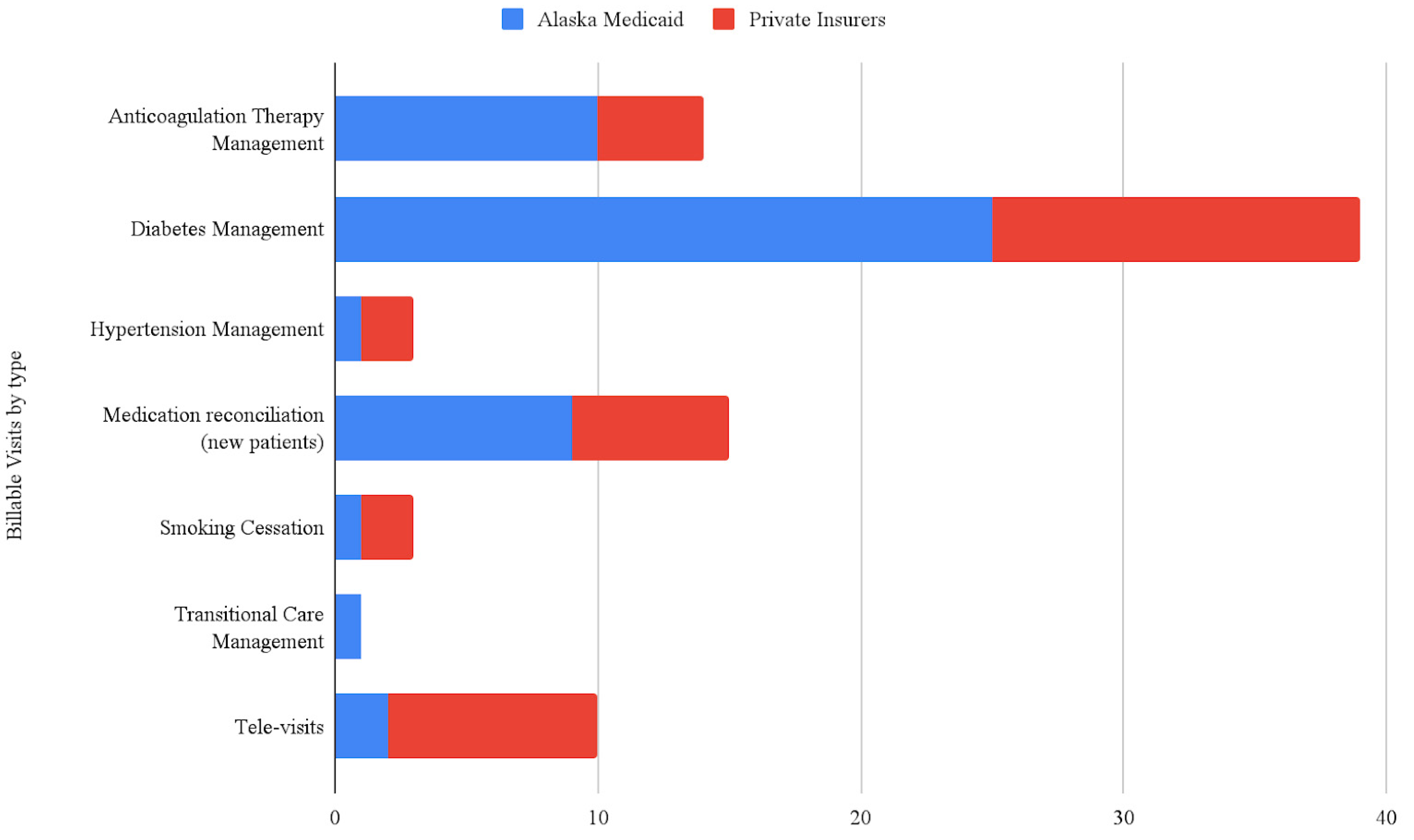

Figure 1 represents the billable services delivered from pilot sites 1 and 2 within the first 18 months, broken down by visit type and payor.

The toolkit will continue to be reviewed and updated to best meet the needs of different practice sites. In Years 3–5, the SETMuPP team efforts will focus on the unique training and resource needs of pharmacists practicing in the community pharmacy setting and adapting the resource toolkit to community pharmacy.

2.2. Integration of Billing into the PharmD Curriculum

Before implementation (Year 0), the integration of billing within the curriculum was topical and found throughout the curriculum without intentional scaffolding. High-level overviews of medication therapy management (MTM) were provided without specific coding-based information. Specific information related to billing for dispensing services was covered via didactic lecture without application activities. Knowledge was assessed via examination and completion of billing case studies. SETMuPP efforts to integrate medical billing in all three years of the didactic curriculum across the project years can be seen in

Figure 2.

Year 1 saw the first iteration of a core mini-module of didactic instruction and lab-based practice specifically focused on billing for pharmacist-provided healthcare services in the outpatient setting. Didactic session activities included the walk-through of a case with sample coding. The lab activities focused on students replicating the coding process with different cases in groups. Feedback was provided by on-site pharmacist facilitators with expertise in medical billing and coding.

Year 2 saw replication of the mini-module of billing and coding from Year 1 and expansion of the curricular scaffolding surrounding billing. A modified, one-hour version of the AKPhA workshop was presented to third-year student pharmacists in preparation for experiential learning. The information presented was designed to be an intentional repetition of the content this cohort of student pharmacists had been exposed to the previous year. Additionally, a foundational five-hour module was added and delivered to first-year student pharmacists.

Year 3 is underway and the original modules from Years 1 and 2 for second-year student pharmacists are being adapted. The material delivered to first-year students has been extensively remodeled so that students are exposed with more intention to the practicalities of insurance in the context of the US healthcare system and how the elements of the cost justification from Year 2 fit into said system. The second-year material has been reformatted to have an emphasis on in-class expert modeling and practice problem solving using a flipped classroom approach. Active pre-work is paired with lab-based independent problem-solving using a wider variety of patient cases. Capstone, the final didactic course in the Doctor of Pharmacy curriculum, will have a one-hour lecture reviewing medical billing and five embedded cases with live standardized patient interactions. The patient simulations are designed to interweave clinical, billing, and patient engagement skills learned throughout the curriculum. Overall, students and faculty support the additional training provided in the program.

2.3. Advocacy and Legislative Support

The advocacy core group conducted an extensive review of Alaska law and established two key findings: (1) pharmacists were already designated as billing medical providers in Alaska state statutes; and (2) delivery of many healthcare services was within the scope of practice for pharmacists in Alaska. From here, the team explored process issues impeding pharmacists from providing healthcare services and submitting claims to the medical benefit. Three major findings from this investigation were (1) pharmacists are already established as billing medical providers under Alaska statute and regulation; (2) pharmacists are not protected under current state provider antidiscrimination law; and (3) the Alaska Medicaid Portal arbitrarily excluded pharmacists from enrollment as providers due to a process error.

The advocacy group created a triad relationship between the UAA/ISU Doctor of Pharmacy Program, AKPhA, and Alaska’s pharmacy regulatory board. The intent of this collaboration is to unify the profession in the state by creating a shared vision, values, and vernacular. Through key collaborations, the advocacy core partnered with Alaska Medicaid to support enrollment of pharmacists as billing providers. Specific meetings were held with the state Insurance Commissioner to get their perspective and support. The Commissioner maintained that it would cost more money to the State to reimburse pharmacists for healthcare services, so they were initially unwilling to provide support for this project moving forward. This response parallels messaging related to attaining pharmacist federal recognition as billing providers under Medicare. Additionally, the Commissioner was unaware of pharmacists’ ability to provide healthcare services and associated the profession exclusively with dispensing activities. This response highlights the ongoing need at state and national levels to spotlight the nondispensing training and skills of the profession. The advocacy group collaborated with AKPhA to meet with legislators to discuss what pharmacists can do to improve access to cost-effective health services. In preparation for these meetings, individuals completed a one-hour training on “how to engage with state legislators”, which was developed and presented by an AKPhA lobbyist; received statistics supporting provider status and billing of the medical benefit; and learned about the SHARP educational support program for Alaska Health Care Students. These meetings helped to establish formal partnerships with the AKPhA legislative group and an action plan for the advocacy group to follow.

The action plan is ongoing and project plans for Years 3–4 are in place. The advocacy group provides ongoing support to recognize pharmacists as health care providers, to promote a shared vernacular, and to establish a unified vision for reimbursement and service access. In Year 2, the advocacy team and AKPhA legislative committee focused on implementation of the unexercised 2015 Senate Bill (SB51). This bill mandated that Alaska Medicaid add pharmacists to the provider-credentialing enrollment portal to support pharmacist billing of the medical and pharmacy benefit for pharmacist-administered vaccinations. However, the Medicaid Portal was not configured to enroll pharmacists as billing providers, creating a procedural “hard stop” for pharmacists seeking to enroll.

Having identified this underlying procedural barrier, the advocacy group contacted and collaborated with the sponsoring legislator of SB51 to identify paths forward and find solutions. The team compiled information in support of these necessary changes and provided these data to the DHSS Director and the Medicaid Pharmacy Program Manager. Data from the DHSS-funded naloxone project and the state Immunization Information System highlighted missed vaccination opportunities. The team consulted with Health and Human Services and Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services experts, who advised that the team focus on the Medicaid State Plan Amendment. The team requested that pharmacists be listed as “Other Provider” to ensure Alaska Medicaid receives matching federal funds. The team provided testimony and comments at the statewide Medicaid scoping meeting, advocating that Medicaid fully implement SB51 by adding pharmacists to the enrollment portal. The SETMuPP advocacy group’s momentum contributed, in part, to Alaska Medicaid finally adding pharmacists to the enrollment portal in June 2020.