The Moderating Effect of Corporate Governance on Corporate Social Responsibility and Information Asymmetry: An Empirical Study of Chinese Listed Companies

Abstract

:1. Introduction

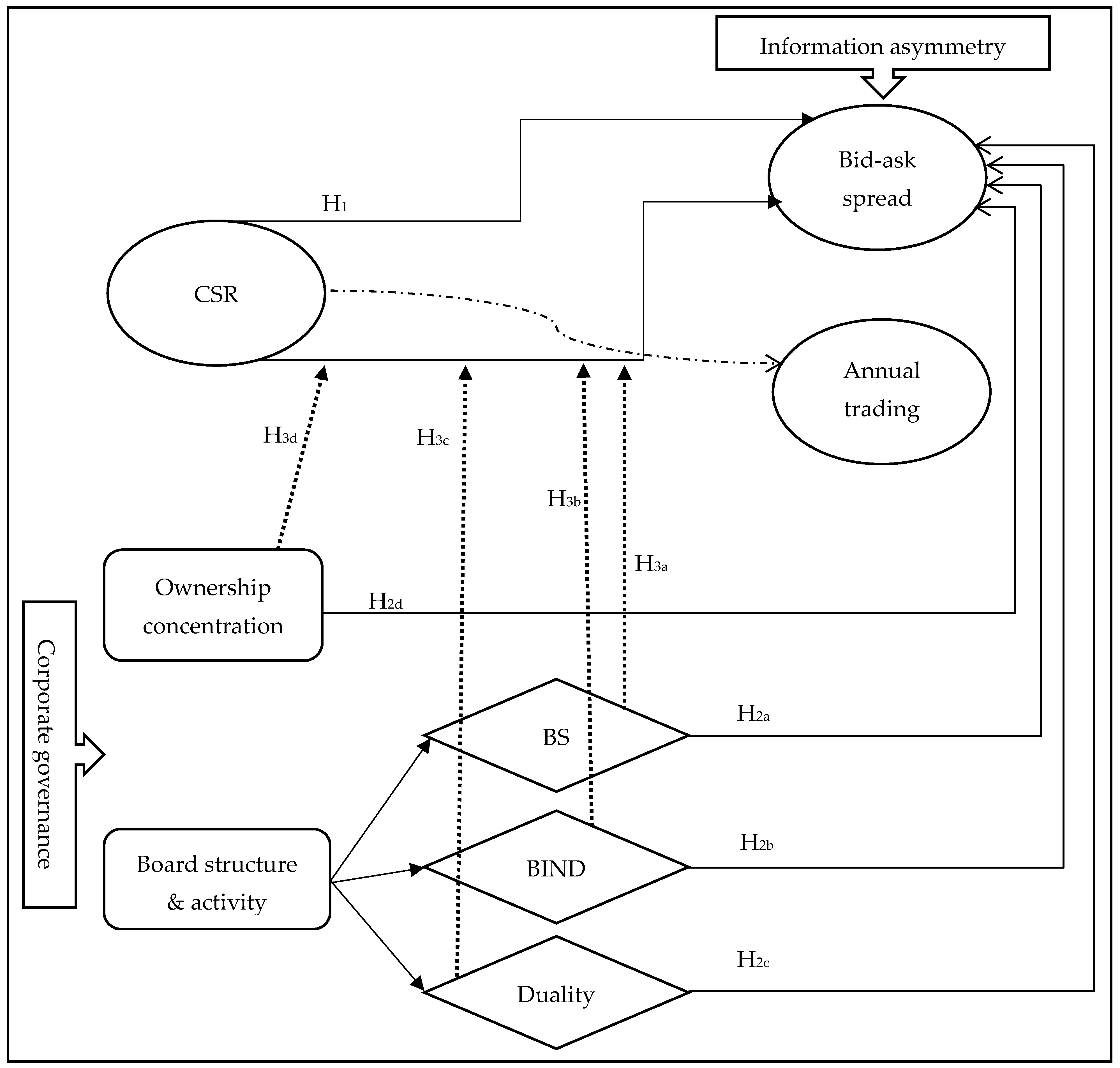

2. Literature Review and the Development of Hypotheses

2.1. CSR and Information Asymmetry

2.2. CG and Asymmetry Information

2.2.1. Board Structure and Information Asymmetry

2.2.2. Ownership Concentration and Information Asymmetry

2.3. The Moderating Influence of CG on CSR Disclosure with Asymmetric Information

3. Research Methodology

3.1. Sample and Data Collection

3.2. Measurements of Variables

3.2.1. Dependent Variable

3.2.2. Independent Variables

3.2.3. Moderation Variables

3.2.4. Control Variables Measures

3.3. Model Specification

4. Data Analysis and Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

4.2. Correlation Matrix

4.3. Results and Discussion

4.3.1. Corporate Social Responsibility and Information Asymmetry

4.3.2. Board Size, Corporate Social Responsibility, and Information Asymmetry

4.3.3. Board Independence, Corporate Social Responsibility, and Asymmetry Information

4.3.4. CEO Duality, Corporate Social Responsibility, and Asymmetric Information

4.3.5. Ownership Concentration, CSR, and Information Asymmetry

4.4. Robustness

5. Conclusions, Limitations, and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abad, David, María Encarnación Lucas-Pérez, Antonio Minguez-Vera, and José Yagüe. 2017. Does Gender Diversity on Corporate Boards Reduce Information Asymmetry in Equity Markets? BRQ Business Research Quarterly 20: 192–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abor, Joshua. 2007. Corporate Governance and Financing Decisions of Ghanaian Listed Firms. Corporate Governance 7: 83–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abu Qa’dan, Mohammad Bassam, and Mishiel Said Suwaidan. 2019. Board Composition, Ownership Structure and Corporate Social Responsibility Disclosure: The Case of Jordan. Social Responsibility Journal 15: 28–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acker, Daniella, Mathew Stalker, and Ian Tonks. 2002. Daily Closing inside Spreads and Trading Volumes around Earnings Announcements. Journal of Business Finance and Accounting 29: 1149–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Adel, Christine, Mostaq M. Hussain, Ehab K. A. Mohamed, and Mohamed A. K. Basuony. 2019. Is Corporate Governance Relevant to the Quality of Corporate Social Responsibility Disclosure in Large European Companies? International Journal of Accounting and Information Management 27: 301–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, Ammad, and Searat Ali. 2017. Boardroom Gender Diversity and Stock Liquidity: Evidence from Australia. Journal of Contemporary Accounting and Economics 13: 148–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Maeeni, Fatima, Nejla Ould Daoud Ellili, and Haitham Nobanee. 2022. Impact of Corporate Governance on Corporate Social Responsibility Disclosure of the UAE Listed Banks. Journal of Financial Reporting and Accounting. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almasria, Nashat Ali. 2021. Determinant Governance Mechanisms Affecting the Quality of Auditing: The External Auditors’ Perceptions Accounting and Financial Studies View Project. British Journal of Economics 18: 38–65. [Google Scholar]

- Almasria, Nashat Ali. 2022a. Corporate Governance and the Quality of Audit Process: An Exploratory Analysis Considering Internal Audit, Audit Committee and Board of Directors. European Journal of Business and Management Research 7: 78–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almasria, Nashat Ali. 2022b. Factors Affecting the Quality of Audit Process “the External Auditors’ Perceptions”. The International Journal of Accounting and Business Society 30: 107–48. Available online: https://ijabs.ub.ac.id/index.php/ijabs/article/view/539 (accessed on 1 January 2022).

- Alves, H. S., N. Canadas, and A. M. Rodrigues. 2015. Voluntary Disclosure, Information Asymmetry and the Perception of Governance Quality: An Analysis Using a Structural Equation Model. Tékhne 13: 66–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ataullah, Ali, Ian Davidson, Hang Le, and Geoffrey Wood. 2014. Corporate Diversification, Information Asymmetry and Insider Trading. British Journal of Management 25: 228–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Chong En, Qiao Liu, Joe Lu, Frank M. Song, and Junxi Zhang. 2004. Corporate Governance and Market Valuation in China. Journal of Comparative Economics 32: 599–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Basuony, Mohamed A. K., K. A. Mohamed Ehab, and Ahmed Mohsen Al-Baidhani. 2015. The Effect of Corporate Governance on Bank Financial Performance: Evidence from the Arabian Peninsula. Corporate Ownership and Control 11: 178–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benlemlih, Mohammed, and Mohammad Bitar. 2018. Corporate Social Responsibility and Investment Efficiency. Journal of Business Ethics 148: 647–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brennan, Niamh M., Collette E. Kirwan, and John Redmond. 2016. Accountability Processes in Boardrooms. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal 29: 135–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Brickley, James A., James S. Linck, and Jeffrey L. Coles. 1999. What Happens to CEOs after They Retire? New Evidence on Career Concerns, Horizon Problems, and CEO Incentives. Journal of Financial Economics 52: 341–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brickley, James A., Jeffrey L. Coles, and Gregg Jarrell. 1997. Leadership Structure: Separating the CEO and Chairman of the Board. Journal of Corporate Finance 3: 189–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchanan, Bonnie, Cathy Xuying Cao, and Chongyang Chen. 2018. Corporate Social Responsibility, Firm Value, and Influential Institutional Ownership. Journal of Corporate Finance 52: 73–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byun, Hae Young, Lee Seok Hwang, and Woo Jong Lee. 2011. How Does Ownership Concentration Exacerbate Information Asymmetry among Equity Investors? Pacific-Basin Finance Journal 19: 511–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Young K., Won Yong Oh, Jae C. Jung, and Jeong Yeon Lee. 2012. Firm Size and Corporate Social Performance: The Mediating Role of Outside Director Representation. Journal of Leadership and Organizational Studies 19: 486–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Yuyuan, Wen He, and Jianling Wang. 2021. Government Initiated Corporate Social Responsibility Activities: Evidence from a Poverty Alleviation Campaign in China. Journal of Business Ethics 173: 661–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Wei Peng, Huimin Chung, Tsui Ling Hsu, and Soushan Wu. 2010. External Financing Needs, Corporate Governance, and Firm Value. Corporate Governance: An International Review 18: 234–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Mei, Dan S. Dhaliwal, and Monica Neamtiu. 2011. Asset Securitization, Securitization Recourse, and Information Uncertainty. The Accounting Review 86: 541–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, Seong Y., Cheol Lee, and Ray J. Pfeiffer. 2013. Corporate Social Responsibility Performance and Information Asymmetry. Journal of Accounting and Public Policy 32: 71–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, Stella, and Oliver M. Rui. 2009. Exploring the Effects of China’s Two-Tier Board System and Ownership Structure on Firm Performance and Earnings Informativeness. Asia-Pacific Journal of Accounting & Economics 16: 95–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, Jaideep, Raman Kumar, and Dilip Shome. 2016. Investment-Cash Flow Sensitivity under Changing Information Asymmetry. Journal of Banking and Finance 62: 28–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Coller, Maribeth, and Teri Lombardi Yohn. 1997. Management Forecasts and Information Asymmetry: An Examination of Bid-Ask Spreads. Journal of Accounting Research 35: 181–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Core, John E., Robert W. Holthausen, and David F. Larcker. 1999. Corporate Governance, Chief Executive Officer Compensation, and Firm Performance. Journal of Financial Economics 51: 371–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Core, John E., Wayne Guay, and David F. Larcker. 2008. The Power of the Pen and Executive Compensation. Journal of Financial Economics 88: 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cormier, Denis, Marie Josée Ledoux, and Michel Magnan. 2010. Corporate Governance and Information Asymmetry between Managers and Investors. Corporate Governance 10: 574–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cormier, Denis, Marie Josée Ledoux, and Michel Magnan. 2011. The Informational Contribution of Social and Environmental Disclosures for Investors. Management Decision 49: 1276–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Jinhua, Hoje Jo, and Haejung Na. 2018. Does Corporate Social Responsibility Affect Information Asymmetry? Journal of Business Ethics 148: 549–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhaliwal, Dan S., Oliver Zhen Li, Albert Tsang, and Yong George Yang. 2011. Voluntary Nonfinancial Disclosure and the Cost of Equity Capital: The Initiation of Corporate Social Responsibility Reporting. Accounting Review 86: 59–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diebecker, Jan, and Friedrich Sommer. 2017. The Impact of Corporate Sustainability Performance on Information Asymmetry: The Role of Institutional Differences. Review of Managerial Science 11: 471–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitropoulos, Panagiotis E., and Dimitrios Asteriou. 2010. The Effect of Board Composition on the Informativeness and Quality of Annual Earnings: Empirical Evidence from Greece. Research in International Business and Finance 24: 190–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Draper, Paul, and Krishna Paudyal. 2008. Information Asymmetry and Bidders’ Gains. Journal of Business Finance & Accounting 35: 376–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwekat, Aladdin, Elies Seguí-Mas, Mohammad A. A. Zaid, and Guillermina Tormo-Carbó. 2021. Corporate Governance and Corporate Social Responsibility: Mapping the Most Critical Drivers in the Board Academic Literature. Meditari Accountancy Research. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elbadry, Ahmed, Dimitrios Gounopoulos, and Frank Skinner. 2015. Governance Quality and Information Asymmetry. Financial Markets, Institutions and Instruments 24: 127–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Eng, Li Li, and Yuen Teen Mak. 2003. Corporate Governance and Voluntary Disclosure. Journal of Accounting and Public Policy 22: 325–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fama, Eugene F., and Michael C. Jensen. 1983. Separation of Ownership and Control. The Journal of Law and Economics 26: 301–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Joseph P. H., and T. J. Wong. 2002. Corporate Ownership Structure and the Informativeness of Accounting Earnings in East Asia. Journal of Accounting and Economics 33: 401–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fehle, Frank. 2004. Bid-Ask Spreads and Institutional Ownership. Review of Quantitative Finance and Accounting 22: 275–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Yi, Abeer Hassan, and Ahmed A. Elamer. 2020. Corporate Governance, Ownership Structure and Capital Structure: Evidence from Chinese Real Estate Listed Companies. International Journal of Accounting and Information Management 28: 759–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Gago, Roberto, Laura Cabeza-García, and Mariano Nieto. 2016. Corporate Social Responsibility, Board of Directors, and Firm Performance: An Analysis of Their Relationships. Review of Managerial Science 10: 85–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrell, Allen, Hao Liang, and Luc Renneboog. 2016. Socially Responsible Firms. Journal of Financial Economics 122: 585–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Firmansyah, Amrie, Mitsalina Choirun Husna, and Maritsa Agasta Putri. 2021. Corporate Social Responsibility Disclosure, Corporate Governance Disclosures, and Firm Value In Indonesia Chemical, Plastic, and Packaging Sub-Sector Companies. Accounting Analysis Journal 10: 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flannery, Mark J., Simon H. Kwan, and M. Nimalendran. 2004. Market Evidence on the Opaqueness of Banking Firms’ Assets. Journal of Financial Economics 71: 419–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Florackis, Chrisostomos, and Aydin Ozkan. 2009. The Impact of Managerial Entrenchment on Agency Costs: An Empirical Investigation Using UK Panel Data. European Financial Management 15: 497–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fosberg, Richard H. 2004. Should The CEO Also Be Chairman Of The Board? Journal of Business & Economics Research (JBER) 2: 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gajewski, Jean François. 1999. Earnings Announcements, Asymmetric Information, Trades and Quotes. European Financial Management 5: 411–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerged, Ali M., and Ahmed Agwili. 2020. How Corporate Governance Affect Firm Value and Profitability? Evidence from Saudi Financial and Non-Financial Listed Firms. International Journal of Business Governance and Ethics 14: 144–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerged, Ali M., Christopher J. Cowton, and Eshani S. Beddewela. 2018. Towards Sustainable Development in the Arab Middle East and North Africa Region: A Longitudinal Analysis of Environmental Disclosure in Corporate Annual Reports. Business Strategy and the Environment 27: 572–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glosten, Lawrence R., and Lawrence E. Harris. 1988. Estimating the Components of the Bid/Ask Spread. Journal of Financial Economics 21: 123–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goh, Beng Wee, Jimmy Lee, Jeffrey Ng, and Kevin Ow Yong. 2016. The Effect of Board Independence on Information Asymmetry. European Accounting Review 25: 155–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Guangming, Si Xu, and Xun Gong. 2018. On the Value of Corporate Social Responsibility Disclosure: An Empirical Investigation of Corporate Bond Issues in China. Journal of Business Ethics 150: 227–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greening, Daniel W., and Daniel B. Turban. 2000. Corporate Social Performance As a Competitive Advantage in Attracting a Quality Workforce. Business & Society 39: 254–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Huimin, Chris Ryan, Li Bin, and Gao Wei. 2013. Political Connections, Guanxi and Adoption of CSR Policies in the Chinese Hotel Industry: Is There a Link? Tourism Management 34: 231–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamrouni, Amal, Mondher Bouattour, Nadia Ben Farhat Toumi, and Rim Boussaada. 2022. Corporate Social Responsibility Disclosure and Information Asymmetry: Does Boardroom Attributes Matter? Journal of Applied Accounting Research 23: 897–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamrouni, Amal, Rim Boussaada, and Nadia Ben Farhat Toumi. 2019. Corporate Social Responsibility Disclosure and Debt Financing. Journal of Applied Accounting Research 20: 394–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haniffa, Roszaini, and Mohammad Hudaib. 2006. Corporate Governance Structure and Performance of Malaysian Listed Companies. Journal of Business Finance and Accounting 33: 1034–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, Lawrence E. 1994. Minimum Price Variations, Discrete Bid–Ask Spreads, and Quotation Sizes. Review of Financial Studies 7: 149–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, Oliver. 1995. Corporate Governance: Some Theory and Implications. The Economic Journal 105: 678–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heflin, Frank, and Kenneth W. Shaw. 2000. Blockholder Ownership and Market Liquidity. The Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis 35: 621–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermalin, Benjamin E., and Michael S. Weisbach. 1988. The Determinants of Board Composition. The RAND Journal of Economics 19: 589–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillier, David, and Patrick McClgan. 2006. An Analysis of Changes in Board Structure during Corporate Governance Reforms. European Financial Management 12: 575–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillman, Amy J., Christine Shropshire, and Albert A. Cannella. 2007. Organizational Predictors of Women on Corporate Boards. Academy of Management Journal 50: 941–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Holm, Claus, and Finn Schøler. 2010. Reduction of Asymmetric Information Through Corporate Governance Mechanisms—The Importance of Ownership Dispersion and Exposure toward the International Capital Market. Corporate Governance: An International Review 18: 32–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Thi, Van Hoang, Wojciech Przychodzen, Justyna Przychodzen, and Elysé A Segbotangni. 2021. Environmental Transparency and Performance: Does the Corporate Governance Matter? Environmental and Sustainability Indicators 10: 100123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, Hafezali Iqbal, Irwan Shah Zainal Abidin, Azlan Ali, and Fakarudin Kamarudin. 2018. Debt Maturity and Family Related Directors: Evidence from a Developing Market. Polish Journal of Management Studies 18: 118–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamalinesari, Shamsaldin, and Hossein Soheili. 2015. The Relationship between Information Asymmetry and Mechanisms of Corporate Governance of Companies in Tehran Stock Exchange. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences 205: 505–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jensen, Michael C., and William H. Meckling. 1976. Theory of the Firm: Managerial Behavior, Agency Costs and Ownership Structure. Journal of Financial Economics 3: 305–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Fuxiu, and Kenneth A. Kim. 2020. Corporate Governance in China: A Survey. Review of Finance 24: 733–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Haiyan, Ahsan Habib, and Baiding Hu. 2011. Ownership Concentration, Voluntary Disclosures and Information Asymmetry in New Zealand. British Accounting Review 43: 39–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jizi, Mohammad. 2017. The Influence of Board Composition on Sustainable Development Disclosure. Business Strategy and the Environment 26: 640–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanagaretnam, Kiridaran, Gerald J. Lobo, and Dennis J. Whalen. 2005. Relationship between Analyst Forecast Properties and Equity Bid-Ask Spreads and Depths around Quarterly Earnings Announcements. Journal of Business Finance and Accounting 32: 1773–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanagaretnam, Kiridaran, Gerald J. Lobo, and Dennis J. Whalen. 2007. Does Good Corporate Governance Reduce Information Asymmetry around Quarterly Earnings Announcements? Journal of Accounting and Public Policy 26: 497–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, ManYing, and Marcel Ausloos. 2017. An Inverse Problem Study: Credit Risk Ratings as a Determinant of Corporate Governance and Capital Structure in Emerging Markets: Evidence from Chinese Listed Companies. Economies 5: 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kang, Sok Hyon, Praveen Kumar, and Hyunkoo Lee. 2006. Agency and Corporate Investment: The Role of Executive Compensation and Corporate Governance. Journal of Business 79: 1127–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Yongtae, Haidan Li, and Siqi Li. 2014. Corporate Social Responsibility and Stock Price Crash Risk. Journal of Banking & Finance 43: 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Klein, April. 2002. Audit Committee, Board of Director Characteristics, and Earnings Management. Journal of Accounting and Economics 33: 375–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Krinsky, Itzhak, and Jason Lee. 1996. Earnings Announcements and the Components of the Bid-Ask Spread. Journal of Finance 51: 1523–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Porta, Rafael, Florencio Lopez-De-Silanes, and Andrei Shleifer. 2002. Government Ownership of Banks. The Journal of Finance 57: 265–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Larcker, David F., Gaizka Ormazabal, and Daniel J. Taylor. 2011. The Market Reaction to Corporate Governance Regulation. Journal of Financial Economics 101: 431–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, Chung Ming, Yuan Lu, and Qiang Liang. 2016. Corporate Social Responsibility in China: A Corporate Governance Approach. Journal of Business Ethics 136: 73–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leuz, Christian, and Robert E. Verrecchia. 2000. The Economic Consequences of Increased Disclosure. Journal of Accounting Research 38: 91–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Feng. 2008. Annual Report Readability, Current Earnings, and Earnings Persistence. Journal of Accounting and Economics 45: 221–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Libby, Theresa, Robert Mathieu, and Sean W. G. Robb. 2002. Earnings Announcements and Information Asymmetry: An Intra-Day Analysis. Contemporary Accounting Research 19: 449–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linck, James S., Jeffry M. Netter, and Tina Yang. 2008. The Determinants of Board Structure. Journal of Financial Economics 87: 308–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lins, Karl V., Henri Servaes, and Ane Tamayo. 2017. Social Capital, Trust, and Firm Performance: The Value of Corporate Social Responsibility during the Financial Crisis. Journal of Finance 72: 1785–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Linsmeier, Thomas J., Daniel B. Thornton, Mohan Venkatachalam, and Michael Welker. 2002. The Effect of Mandated Market Risk Disclosures on Trading Volume Sensitivity to Interest Rate, Exchange Rate, and Commodity Price Movements. Accounting Review 77: 343–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Yatian, Heng Xu, and Xiaojie Wang. 2021. Government Subsidy, Asymmetric Information and Green Innovation. Kybernetes. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Jintao, Mengshang Liang, Chong Zhang, Dan Rong, Hailing Guan, Kristina Mazeikaite, and Justas Streimikis. 2021. Assessment of Corporate Social Responsibility by Addressing Sustainable Development Goals. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management 28: 686–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnanelli, Barbara Sveva, and Maria Federica Izzo. 2017. Corporate Social Performance and Cost of Debt: The Relationship. Social Responsibility Journal 13: 250–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marquis, Christopher, and Cuili Qian. 2014. Corporate Social Responsibility Reporting in China: Symbol or Substance? Organization Science 25: 127–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Martínez-Ferrero, Jennifer, and Isabel María García-Sánchez. 2015. Is Corporate Social Responsibility an Entrenchment Strategy? Evidence in Stakeholder Protection Environments. Review of Managerial Science 9: 89–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Ferrero, Jennifer, Lázaro Rodríguez-Ariza, Isabel María García-Sánchez, and Beatriz Cuadrado-Ballesteros. 2018. Corporate Social Responsibility Disclosure and Information Asymmetry: The Role of Family Ownership. Review of Managerial Science 12: 885–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGuinness, Paul B., João Paulo Vieito, and Mingzhu Wang. 2017. The Role of Board Gender and Foreign Ownership in the CSR Performance of Chinese Listed Firms. Journal of Corporate Finance 42: 75–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Michaels, Anne, and Michael Grüning. 2017. Relationship of Corporate Social Responsibility Disclosure on Information Asymmetry and the Cost of Capital. Journal of Management Control 28: 251–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, Nancy, and Ahmed Rashed. 2021. An Investigation of the Relationship between Corporate Social Responsibility and Corporate Financial Performance in Egypt: The Mediating Role of Information Asymmetry. Journal of Accounting, Business and Management (JABM) 28: 73–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naqvi, Syeda Khiraza, Faisal Shahzad, Ijaz Ur Rehman, Fiza Qureshi, and Usama Laique. 2021. Corporate Social Responsibility Performance and Information Asymmetry: The Moderating Role of Analyst Coverage. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management 28: 1549–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ness, Bonnie F. Van, Robert A. Van Ness, and Richard S. Warr. 2001. How Well Do Adverse Selection Components Measure Adverse Selection? Financial Management 30: 77–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, Van Ha, Frank W. Agbola, and Bobae Choi. 2019. Does Corporate Social Responsibility Reduce Information Asymmetry? Empirical Evidence from Australia. Australian Journal of Management 44: 188–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Neill, Michele, and Judith Swisher. 2003. Institutional Investors and Information Asymmetry: An Event Study of Self-Tender Offers. Financial Review 38: 197–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, Won-Yong, Young Kyun Chang, and Tae-Yeol Kim. 2018. Complementary or Substitutive Effects? Corporate Governance Mechanisms and Corporate Social Responsibility. Journal of Management 44: 2716–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawlina, Grzegorz, and Luc Renneboog. 2005. Is Investment-Cash Flow Sensitivity Caused by Agency Costs or Asymmetric Information? Evidence from the UK. European Financial Management 11: 483–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Peasnell, Ken V., Peter F. Pope, and Steven Young. 2005. Board Monitoring and Earnings Management: Do Outside Directors Influence Abnormal Accruals? Journal of Business Finance & Accounting 32: 1311–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Chih Wei, and Mei Ling Yang. 2014. The Effect of Corporate Social Performance on Financial Performance: The Moderating Effect of Ownership Concentration. Journal of Business Ethics 123: 171–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Mikew. 2004. Outside Directors and Firm Performance during Institutional Transitions. Strategic Management Journal 25: 453–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perotti, Enrico C., and Ernst-Ludwig von Thadden. 2003. Strategic Transparency and Informed Trading: Will Capital Market Integration Force Convergence of Corporate Governance? The Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis 38: 61–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pham, Hanh Song Thi, and Hien Thi Tran. 2020. CSR Disclosure and Firm Performance: The Mediating Role of Corporate Reputation and Moderating Role of CEO Integrity. Journal of Business Research 120: 127–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahayu, Ruri, Gugus Irianto, and Arum Prastiwi. 2021. The Effect of Earnings Management and Media Exposure on Corporate Social Responsibility Disclosure with Corporate Governance as a Moderating Variable. International Journal of Research in Business and Social Science 10: 220–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehman, Ijaz Ur, Syeda Khiraza Naqvi, Faisal Shahzad, and Ahmed Jamil. 2022. Corporate Social Responsibility Performance and Information Asymmetry: The Moderating Role of Ownership Concentration. Social Responsibility Journal 18: 424–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutherford, Matthew A., and Ann K. Buchholtz. 2007. Investigating the Relationship Between Board Characteristics and Board Information. Corporate Governance: An International Review 15: 576–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salehi, Hamid, Hamideh Rezaie, and Farideh Ansari. 2014. Corporate Governance and Information Asymmetry. Management Science Letters 4: 1829–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shan, Yuan George, Joey Wenling Yang, Junru Zhang, and Millicent Chang. 2022. Analyst Forecast Quality and Corporate Social Responsibility: The Mediation Effect of Corporate Governance. Meditari Accountancy Research. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shleifer, Andrei, and Robert W. Vishny. 1997. A Survey of Corporate Governance. The Journal of Finance 52: 737–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Yang, Huu Nhan Duong, and Harminder Singh. 2014. Information Asymmetry, Trade Size, and the Dynamic Volume-Return Relation: Evidence from the Australian Securities Exchange. Financial Review 49: 539–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Switzer, Lorne N., and Jun Wang. 2013. Default Risk Estimation, Bank Credit Risk, and Corporate Governance. Financial Markets, Institutions & Instruments 22: 91–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tessema, Abiot. 2019. The Impact of Corporate Governance and Political Connections on Information Asymmetry: International Evidence from Banks in the Gulf Cooperation Council Member Countries. Journal of International Accounting, Auditing and Taxation 35: 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, Md Shahid, Mohammad Badrul Muttakin, and Arifur Khan. 2019. Corporate Governance and Corporate Social Responsibility Disclosures in Insurance Companies. International Journal of Accounting & Information Management 27: 284–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallace, R. S. Olusegun, Kamal Naser, and Araceli Mora. 1994. The Relationship Between the Comprehensiveness of Corporate Annual Reports and Firm Characteristics in Spain. Accounting and Business Research 25: 41–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Kun Tracy, and Dejia Li. 2016. Market Reactions to the First-Time Disclosure of Corporate Social Responsibility Reports: Evidence from China. Journal of Business Ethics 138: 661–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Zhihong, Tien Shih Hsieh, and Joseph Sarkis. 2018. CSR Performance and the Readability of CSR Reports: Too Good to Be True? Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management 25: 66–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welker, MIichael. 1995. Disclosure Policy, Information Asymmetry, and Liquidity in Equity Markets. Contemporary Accounting Research 11: 801–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widyansyah, Ahmad Surya, Amrie Firmansyah, Dani Kharismawan Prakosa, and Much Rizal Pua Geno. 2021. Risk Relevance of Comprehensive Income in Indonesia: The Role of Corporate Social Responsibility, Good Corporate Governance, Tax Avoidance. International Business and Accounting Research Journal 5: 118–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, Cheng, Fengwen Chen, Paul Jones, and Senmao Xia. 2021. The Effect of Institutional Investors’ Distraction on Firms’ Corporate Social Responsibility Engagement: Evidence from China. Review of Managerial Science 15: 1645–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Shan, Duchi Liu, and Jianbai Huang. 2015. Corporate Social Responsibility, the Cost of Equity Capital and Ownership Structure: An Analysis of Chinese Listed Firms. Australian Journal of Management 40: 245–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, Yuyang, Zongyi Zhang, and Cheng Xiang. 2022. The Value of CSR during the COVID-19 Crisis: Evidence from Chinese Firms. Pacific-Basin Finance Journal 74: 101795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Minna, and Yanming Wang. 2018. Firm-Specific Corporate Governance and Analysts’ Earnings Forecast Characteristics: Evidence from Asian Stock Markets. International Journal of Accounting and Information Management 26: 335–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Yin, and Jing Chi. 2021. Political Embeddedness, Media Positioning and Corporate Social Responsibility: Evidence from China. Emerging Markets Review 47: 100799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Jian, Dongmin Kong, and Ji Wu. 2018. Doing Good Business by Hiring Directors with Foreign Experience. Journal of Business Ethics 153: 859–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Qian, Bee Lan Oo, and Benson Teck Heng Lim. 2022. Linking Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) Practices and Organizational Performance in the Construction Industry: A Resource Collaboration Network. Resources, Conservation and Recycling 179: 106113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zu, Liangrong, and Lina Song. 2009. Determinants of Managerial Values on Corporate Social Responsibility: Evidence from China. Journal of Business Ethics 88: 105–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| N | Mean | Median | SD | Minimum | Maximum | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BAspd | 8358 | −2.396 | −1.846 | 5.911 | −12.666 | 54.956 |

| CSR | 8358 | −2.636 | −2.191 | 8.063 | −18.45 | 82.434 |

| ATV | 8358 | 23.655 | 23.609 | 1.103 | 17.181 | 28.533 |

| BS | 8358 | 23.149 | 22 | 5.175 | 11 | 66 |

| BIND | 8358 | 0.147 | 0.143 | 0.022 | 0.032 | 0.273 |

| Duality | 8358 | 0.194 | 0 | 0.396 | 0 | 1 |

| OC | 8358 | 31.572 | 30.466 | 18.315 | 0.06 | 89.41 |

| SIZE | 8358 | 22.137 | 21.815 | 1.704 | 15.418 | 30.815 |

| BTM | 8358 | 770.155 | 535.709 | 1140.110 | −14,045.56 | 30,459.27 |

| LEV | 8358 | 0.532 | 0.489 | 1.525 | 0 | 96.959 |

| ROA | 8358 | 0.035 | 0.038 | 0.247 | −20.548 | 0.98 |

| BAspd | ATV | CSR | BS | BIND | Duality | OC | SIZE | BTM | LEV | ROA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BAspd | — | ||||||||||

| ATV | −0.128 *** | — | |||||||||

| CSR | 0.329 *** | −0.222 *** | — | ||||||||

| BS | 0.023 * | 0.286 *** | −0.068 *** | — | |||||||

| BIND | −0.001 | −0.085 *** | 0.021 | −0.381 *** | — | ||||||

| Duality | 0.063 *** | −0.131 *** | 0.074 *** | −0.168 *** | 0.034 ** | — | |||||

| OC | −0.031 ** | −0.011 | −0.001 | −0.005 | 0.006 | −0.041 *** | — | ||||

| SIZE | 0.035 ** | 0.624 *** | −0.139 *** | 0.432 *** | −0.111 *** | −0.186 *** | 0.108 *** | — | |||

| BTM | 0.161 *** | −0.222 *** | 0.084 *** | 0.126 *** | −0.01 | 0.001 | 0.164 *** | 0.278 *** | — | ||

| LEV | −0.116 *** | 0.227 *** | −0.112 *** | 0.242 *** | −0.065 *** | −0.18 *** | −0.028 * | 0.45 *** | −0.13 *** | — | |

| ROA | 0.128 *** | −0.023 * | 0.077 *** | −0.039 *** | −0.014 | 0.088 *** | 0.089 *** | −0.067 *** | 0.015 | −0.47 *** | — |

| Dependent Variable—Information Asymmetry (Bid–ask Spread) | |

|---|---|

| Predictor | Model (1) |

| CSR | −3.163 *** |

| (0.078) | |

| BTM | 0.512 *** |

| (0.109) | |

| SIZE | 0.005 |

| (0.937) | |

| LEV | −2.096 *** |

| (0.503) | |

| ROA | 3.637 ** |

| (1.501) | |

| Constant | −5.927 *** |

| (1.223) | |

| Observations | 8358 |

| R | 0.717 |

| R2 | 0.515 |

| Dependent Variable—Bid–ask Spread (BAspd) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictor | Model (2) | Model (3) | Model (4) | Model (5) |

| CSR | −3.113 ** | −2.987 *** | −3.282 *** | −1.821 *** |

| (0.082) | (0.079) | 0.078 | (0.082) | |

| BS | 0.031 ** | |||

| (0.012) | ||||

| CSR × BS | 0.012 *** | |||

| (0.000) | ||||

| BIND | −28.691 *** | |||

| (3.875) | ||||

| CSR × BIND | 4.266 *** | |||

| (0.068) | ||||

| Duality | 0.696 ** | |||

| (0.228) | ||||

| CSR × Duality | 0.033 * | |||

| (0.016) | ||||

| OC | 0.409 ** | |||

| (0.137) | ||||

| CSR × OC | 0.013 *** | |||

| (0.000) | ||||

| BTM | 0.154 ** | 0.584 *** | 0.000 *** | 0.599 *** |

| (0.071) | (0.111) | (0.000) | (0.128) | |

| SIZE | 0.372 *** | 0.009 | −0.099 | 0.115 |

| (0.047) | (0.068) | (0.060) | (0.077) | |

| LEV | −0.311 *** | −2.102 *** | 0.026 | −2.919 *** |

| (0.321) | (0.513) | (0.561) | (0.583) | |

| ROA | 1.561 * | 4.112 ** | −0.318 | 5.130 ** |

| (0.816) | (1.529) | (0.232) | 1.746 | |

| Constant | −11,123 *** | −2.217 | −1.516 | −5.516 *** |

| (0.776) | 0.114 | (0.191) | 1.490 | |

| Observations | 8255 | 8255 | 82555 | 8255 |

| R | 0.563 | 0.705 | 0.719 | 0.589 |

| R2 | 0.317 | 0.497 | 0.517 | 0.347 |

| Dependent Variable—Annual Trading Value (ATV) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictor | Model (6) | Model (7) | Model (8) | Model (9) | Model (10) |

| CSR | 0.010 ** | 0.007 * | 0.009 ** | 0.010 ** | 0.006 * |

| (0.003) | (0.003) | (0.003) | (0.003) | (0.003) | |

| BS | −0.004 *** | ||||

| (0.001) | |||||

| CSR*BS | −0.000 * | ||||

| (0.000) | |||||

| BIND | 0.263 *** | ||||

| (0.045) | |||||

| CSR*BIND | −0.009 *** | ||||

| (0.003) | |||||

| Duality | −0.038 *** | ||||

| (0.009) | |||||

| CSR*Duality | −0.000 | ||||

| (0.001) | |||||

| OC | −0.025 *** | ||||

| (0.005) | |||||

| CSR*OC | −0.000 ** | ||||

| (0.000) | |||||

| BTM | −0.958 *** | −0.000 *** | −0.958 *** | −0.957 *** | −0.963 *** |

| (0.004) | (0.000) | (0.004) | (0.004) | (0.004) | |

| SIZE | 0.941 *** | 0.949 *** | 0.940 *** | 0.939 *** | 0.939 *** |

| (0.004) | (0.003) | 0.003 | (0.003) | (0.003) | |

| LEV | −1.998 *** | −1.980 *** | −1.996 *** | −2.010 *** | −1.997 *** |

| (0.020) | (0.020) | (0.020) | (0.020) | (0.20) | |

| ROA | 0.493 *** | 0.491 *** | 0.466 *** | 0.494 *** | 0.463 *** |

| (0.59) | (0.58) | (0.059) | (0.059) | (0.059) | |

| Constant | 1.198 *** | 0.865 *** | 1.143 *** | 1.229 *** | 1.274 *** |

| (0.048) | (0.054) | (0.049) | (0.049) | (0.051) | |

| Observations | 8117 | 8117 | 8117 | 8117 | 8117 |

| R | 0.988 | 0.989 | 0.988 | 0.988 | 0.988 |

| R2 | 0.977 | 0.977 | 0.977 | 0.977 | 0.977 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Alduais, F.; Almasria, N.A.; Airout, R. The Moderating Effect of Corporate Governance on Corporate Social Responsibility and Information Asymmetry: An Empirical Study of Chinese Listed Companies. Economies 2022, 10, 280. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies10110280

Alduais F, Almasria NA, Airout R. The Moderating Effect of Corporate Governance on Corporate Social Responsibility and Information Asymmetry: An Empirical Study of Chinese Listed Companies. Economies. 2022; 10(11):280. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies10110280

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlduais, Fahd, Nashat Ali Almasria, and Rana Airout. 2022. "The Moderating Effect of Corporate Governance on Corporate Social Responsibility and Information Asymmetry: An Empirical Study of Chinese Listed Companies" Economies 10, no. 11: 280. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies10110280