1. Introduction

In the digitalized world, the number of Internet users is growing rapidly. The share of the world’s population with Internet connection reached 46.1% in 2016 (

ILS 2016). This share increased to 59.5% at the beginning of 2021 (

Statista 2022a). In line with the increasing number of Internet users and seasonal COVID restriction or lockdowns, e-commerce is expected to grow more than before over the next years. In 2021, retail e-commerce sales amounted to 4.9 trillion US dollars worldwide. It is forecasted to grow by 50% over the next years, reaching about 7.4 trillion dollars by 2025 (

Statista 2022b).

The wine business can be highly influenced by online marketing platforms. The United Kingdom is the leading market for online wine business, estimated at 11% of its total wine sales (

CBI 2016). Purchasing alcohol online is overcoming other consumer goods at a rate of 59.8% compared to 53.2% of the pre-COVID period in the United States. Online wine continues to grow with a share of 68%, compared to spirits (18%) and beer (13%) (

Harfmann 2021). Behind e-commerce, social media (SM) became common due to its many advantages such as global consumer access.

The share of individuals purchasing on the Internet has a growing trend in the European Union from 40% to 63%, as well as in Hungary from 18% to 49%, between 2010 and 2019 (

Eurostat 2020). Additionally, the growth of Hungarian online B2C e-commerce sales was 9% in 2019 (

ecommerceDB 2020). Wine accounted for the largest share of online drink sales in Hungary, reaching 19% in November–December 2020 (

Statista 2021) which predicts a compound annual growth rate for the next years.

In Hungary’s wine business, wine sales can benefit more from the possibilities of digital marketing and SM usage in the future. At this time, Facebook is strongly represented in the online wine business. This social media platform is number one in the United States and Germany (

Szolnoki and Hoffmann 2014;

Szolnoki et al. 2016). Instagram is largely used worldwide by people aged 34 years and younger which makes this platform particularly attractive for marketers (

Statista 2022c).

Young people’s wine consumption is not as conscious and changes gradually as they get older. In general, the frequency of wine consumption increases with age (

Dula et al. 2012). However, as age increases, the propensity to buy wine online decreases, 22% of consumers under 30 years consider online wine shopping feasible, but less than 5% over 65 in Hungary (

Totth and Szolnoki 2019). The majority of consumers with more sophisticated wine knowledge and needs are from the older generations, especially the Baby Boom generation (born between 1946 and 1964). However, this generation is less likely to have an intensive digital presence and to shop online (

Obermayer et al. 2019). The reasons for avoiding buying wine online are buying other products online or not being able to taste the wine (

Totth and Szolnoki 2019).

Although online sales, and social media usage are becoming more popular in the Hungarian wine business and among wine buyers, there are limited studies in the wine economics literature (

Szolnoki et al. 2014,

2016;

Totth and Szolnoki 2019;

Obermayer et al. 2022) investigating online wine sales and their social media usage. There is a lack of literature exploring the impact of online marketing activities on the profitability of online wine shops.

The objective of the paper is to analyze the marketing activity of online wine shops on their profitability in Hungary. In the analysis, we focus on the main domestic players of the online wine sales and the marketing activities of online wine shops in Hungary, employing qualitative data collection techniques and quantitative data analysis.

More specifically, the paper employs a web-content analysis of the twelve most important online wine shops in Hungary. The study focuses on the marketing mix-based activities of the online wine shops including marketing 4Ps concept. Furthermore, descriptive statistical analysis was performed on the sample data.

The article is structured as follows.

Section 2 presents an overview of the conceptual framework with a detailed overview of the online marketing activities of the wine shops. This is based on the marketing mix 4Ps concept and broken down by international and Hungarian sections. This is followed by the description of the data and the method used.

Section 4 outlines the recent trends of the Hungarian wine market and wine industry.

Section 5 presents the results of the qualitative analysis.

2. Theoretical Background

Marketing comprises a wide range of activities in business strategy. The marketing mix is a foundation model for marketing.

Kotler (

2000, p. 9) defined this as the ‘set of marketing tools that the firm uses to pursue its marketing objectives in the target market’. One of the most well-known frameworks was introduced by

McCarthy (

1960,

1964), the so-called 4Ps (Product, Price, Place, Promotion). After the concept of 4P, the extended marketing mix (7P) was developed which added 3 new elements (People, Processes, Physical Evidence) to the original 4Ps. Market segmentation is one of the most common tools for analyzing online wine markets based on the 4Ps concept as a marketing tool commonly used since the early 1990s (

Bonn et al. 2018). Today, online marketing activities including social media use are more and more important in wine business and play an important role in their profitability.

Thach et al. (

2016) suggest that using multiple social media platforms can significantly increase wine sales. Wine marketers in the United States would benefit from adopting social media into their marketing mix.

Szolnoki et al. (

2014) added that Facebook fan wineries had a higher turnover compared to the non-Facebook fans in Germany; therefore, they are more open to receiving sales offers from the company which they support. Considering the literature addressing the analysis of online wine marketing, international and Hungarian studies are discussed.

2.1. International Studies on Online Wine Marketing

Regarding the online wine marketing literature, several studies addressed initiating consumer behavior by online marketing tools.

Pomarici et al. (

2017) found that wine attributes have a significant impact on consumer choice; therefore, appropriate marketing mix should be used to initiate their behavior. The two most preferred attributes of US consumers were “tasted the wine previously” and “someone recommended it”; therefore, they should be incorporated into marketing strategies. Based on the Best-Worst Scale (BWS) scores, they identified the following segments: experientials, connoisseurs, risk minimizers, and price sensitives. These results are also in line with the early work of

Spawton (

1991).

Yabin and Li (

2019) segmented the Chinese online wine market by wine-related lifestyle and found similar segments in China to what was found earlier in Australia by

Bruwer et al. (

2001). Five segments were identified: wine business consumption style, wine enthusiast consumption type, wine enjoyment consumption type, wine fashion consumption type, and wine novice consumption type.

Other articles analyzed the production side of the online wine business. Researchers and winemakers have found that the growth of the wine industry has resulted in a variety of successful marketing strategies, building a respectable brand, and upselling wine products. Using social media such as Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, YouTube, etc., the wine industry has added an advantage to its current marketing ability (

Pulizzi 2010). Value within social media, specifically Twitter, was recognized as early as 2012 (

Wilson and Quinton 2012).

Capitello et al. (

2014) stated that ‘personification’, which works in the offline environment, can also work in the online web-based environment. However, most of the Italian wineries analyzed used web 2.0 technologies as a one-way communication flow, which should be improved. Contrary to these results, based on data from 280 South Italian wineries,

Fiore et al. (

2016) found that companies with digital strategies have better knowledge of consumer needs and expectations due to fast and two-way communication, which can improve the final product.

Taking social media (SM) into account,

Chung et al. (

2014) identified three different dimensions of the engagement of firms in SM: intensity (basically the number of posts and comments divided by the number of fans), richness (the quality of the firm’s SM activities), and responsiveness (the degree of interaction between firms and consumers).

Aspasia and Ourania (

2015) applied this to Greek manufacturing firms. They found that the web is a cost-efficient tool.

Social media sites are becoming increasingly important, and, e.g., Facebook can be used as a brand and retail communication tool (

Dolan and Goodman 2017). Optimizing, e.g., Facebook advertising, it is important to provide more personalized messages to customers and offer incentives and promotions to encourage them to pass on messages (

Dehghani and Tumer 2015). This is closely related to the purchase intention of consumers.

Galati et al. (

2017) analyzed the Sicilian wine region. They found that the smaller Sicilian wineries were more active on Facebook, which is a cheaper communication channel compared to the non-virtual channels. Larger companies used traditional tools more. Furthermore, more educated managers were more open about using SM. Based on the survey of 375 US wineries,

Thach et al. (

2016) found that 87% of them perceived increased sales from SM efforts, and Facebook was identified as a ‘gateway’ platform. However, using multiple platforms results in the highest revenue. They highlighted that consumer feedback should be treated with special attention.

The main advantage of SM platforms is the rapid exchange of information, which can encourage consumers to try different wines (

Wilson and Quinton 2012). However, in the case of a web-based wine business, the value of website quality plays an important role at both the individual and the firm level (

Cho et al. 2014). The use of SM in the wine industry is of particular importance if tourism plays an important role in the given region (

Canovi and Pucciarelli 2019).

A special subgroup of new wine drinkers are the so-called Millennials, and more recently, Generation Z. As they are the new consumers, more targeted marketing is essential. As

Atkin and Thach (

2012) highlighted, they use smart phones to get information, and friends and family are more important sources of information compared to the elders. Based on their results, social networking and online media play an important role in the Millennials’ life; therefore, they are of strategic importance. Stronger friend and family impacts can be explained by their higher interconnections compared to previous generations, so different ways of increasing their knowledge, for example, wine tastings, different types of knowledge transfer, can result in changes in their preferences and consumption (

Foroudi et al. 2019). These differences can be observed at the winemaking level, as, e.g.,

Canovi and Pucciarelli (

2019) obtained that older northern Italian managers preferred traditional marketing tools and tried to concentrate on wine making. More than 11,000 French, German, UK, US, and Canadian wine consumers were analyzed in

Mueller et al.’s (

2011) research. One of their remarkable findings was the difference between the driver of wine consumption: younger generations in the North American markets, but older generations in the European markets. Therefore, even Gen-Y wine consumers should be reached differently depending on the location of the market.

Charters et al. (

2011) analyzed focus groups with 174 participants from Australia, New Zealand, South Africa, the United Kingdom, and the United States. They found lifecycle more influential than generation and highlighted the importance of deeper segmentation, e.g., by gender, especially if sparkling wine is the marketed product. Understanding local markets is of utmost importance.

2.2. Hungarian Studies on Online Wine Marketing

Although research on the use of social media and online marketing in wine business has already begun, only a few articles can be found in this field, particularly those dealing with the profitability of Hungary’s online wine shops.

Szolnoki et al. (

2014) highlighted that traditional communication tools have lost their dominance, while online platforms have become very popular all over the world recently. In terms of using SM for communication, overseas countries seem to be leading the way. However, telecommunication is still important in Europe and Hungary, experiencing a downward trend compared to Internet-based tools (

Szolnoki et al. 2014). In turn, a large majority of wineries in California used websites (98%) and social media (93%) as part of their marketing strategy; in contrast, significantly fewer wineries were using traditional advertising tools than before. Facebook proved to be the main platform with a market share of 94% among wineries using SM in Hungary (

Szolnoki et al. 2016).

Szerb and Szerb (

2020) analyzed Hungarian wineries and highlighted the importance of new marketing tools in reaching new consumers. They also found that the economic performance of wineries correlates with their locations/wine regions.

Recent trends show that Hungary’s wine shoppers tend to buy wines in wine shops or wine cellars, but they are more open to purchasing wines online. The latest research on Hungarian wine consumption was carried out in 2017 on a representative sample of 1501 people (

Totth and Szolnoki 2019). According to their results, 53% of wine is consumed at home, followed by as a guest (25%), and restaurants (13%). The main sources of wine purchases are hypermarkets (30%), smaller grocery stores (20%), and supermarkets (19%). In Hungary, a significant share of consumers under the age of 30 (22%) consider online wine shopping feasible, but it is not held for elderly buyers (5%) (

Totth and Szolnoki 2019). However, only 10% of the Hungarian consumers ordered wine online in 2018, this value increased to 25% by 2021 (

Kabarcz-Horváth 2022). This growth was accelerated by the COVID-19 pandemic-related measures.

Obermayer et al. (

2022) concluded that Facebook was the most popular social media tool that wineries use to increase brand awareness and reach new potential customers in the Balaton wine region of Hungary. In conclusion, there are no relevant articles that analyze online marketing or social media activity on the profitability of online wine stores in Hungary.

3. Data and Method

First, the research used a web content analysis of the 12 most important online wine stores. Second, this was analyzed using statistical methods (descriptive statistics, graphical and correlation analysis). More specifically, a marketing mix-based research was conducted focusing on the impact of online wine sales and SM usage as a promotion/communication tool on the profitability of online wine shops in Hungary. The study reflects each element of the marketing mix (the aspects of 4Ps), including the use of the online platforms and social media as an important factor in the communication mix (promotion). These channels allow two-way communication between sellers and consumers, or among actual and potential consumers by using different applications (e.g., homepages, blogs or different networking sites), which is called wine 2.0 (

Thach 2009).

This research aims to investigate the impact of the use of online marketing tools and social media activity of the Hungarian online wine shops and to present how this is related to their profitability. To obtain a clearer picture of marketing and promotion activities together with the use of the Internet and social networks of the most relevant Hungarian players, the top 12 online wine stores were selected for the study based on their sales volume, popularity and public data availability on their websites.

The web content analysis covers the most important contents of the wine shops’ websites (age of the company, wine assortment, highest and lowest wine prices, services, number of offline stores, etc.), and their social media usage (Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, Pinterest profiles, and YouTube channels), carried out in January 2022. Profitability data were derived from their financial reports of the wine shops publicly available. The aim of the article is to identify the potential links between the above-mentioned variables and profitability of the analyzed online wine shops.

4. The Hungarian Wine Market

4.1. Trends in Wine Consumption

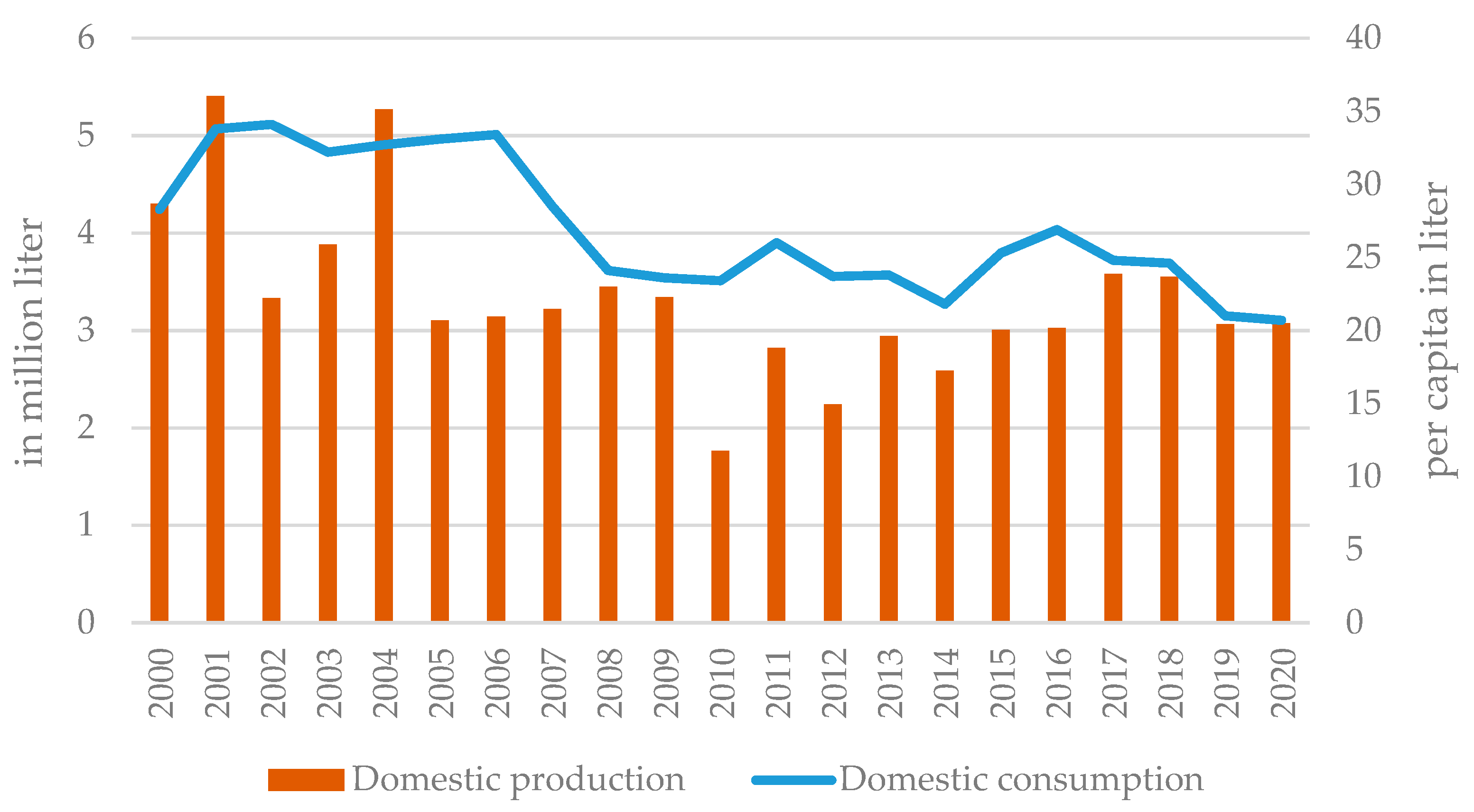

The Hungarian wine market reached its maturity as per capita consumption fluctuated around 25 L in the last 11 years, reaching 20 L in 2020; domestic production also decreased continuously since 2016 (

Figure 1). The first indicates that the market size is expected to be stable with a decreasing tendency; therefore, a higher market share can only be reached at the expense of the other competitors. Under these circumstances, online marketing will play an even more important role in attracting new consumers. Hungarian wine consumers are rather patriotic; approximately 90% of them prefer to drink domestic wine products (

Borászportál 2016).

The result of the Great Wine Test survey conducted in 2012 on wine buying and consumption habits in Hungary suggests that consumers buy 40% of wines in wine shops. It indicates that demand is strongly shifting toward professional Hungarian wine shops, such as Bortársaság and Borháló (

OPH 2016). According to the results of the second Hungarian Great Wine Tests survey, only 10% of the respondents ordered wine online in 2018, while this value increased to 25% by 2021 (

Kabarcz-Horváth 2022). This remarkable growth was accelerated by the COVID-19 pandemic due to strict lockdown measures. It shows that in the post-COVID period, online marketing has significant importance to increase wine sales in Hungary.

4.2. Use of the Internet and Social Media in the Wine Business

The use of the Internet and SM of the Hungarian wine business is fairly understudied in the scientific literature.

Szolnoki et al. (

2014) conducted a relevant survey in this field of research. Based on their results, Hungarian wineries mainly used personal (60%) and e-mail communication (47%) to stay in contact with their customers. Their results show that most Hungarian wineries have Facebook profiles (39%) and read blogs (20%). In contrast, they rarely create their own blog (4%) and comment on them (10%) to advertise themselves. Furthermore, they rarely use Twitter, Pinterest, or Instagram to communicate with their clients (

Szolnoki et al. 2014).

A winery survey of

Tóth et al. (

2014) demonstrated that Hungary’s wineries try to optimize their expenditures and would like to generate maximum revenue while minimizing expenses. The authors identified three groups of producers. Well-capitalized producers use a wide range of marketing communication tools, including TV ads. The second group applied cost-efficient methods with high use of the Internet, while the producers of the third group tried to provide real experience and concentrated on, e.g., wine tastings.

SM became the most important source of information for younger generations (Y and Z), strengthened by the fact that 85% of the Hungarian population had a smart phone and the share of SM usage was 81% in 2017 (

e-Net 2018). Based on a recent empirical study, Facebook (33%), Gasztroblog (19%), and Instagram (14%) were the main sources of information on wineries, while Facebook (39%), YouTube (16%), and Instagram (15%) were the main sources of information on wine-related programs (

Obermayer et al. 2019). Among SM platforms, Facebook is the leading source of information on wineries or wine events.

4.3. Online Wine Shops in Hungary

Bortársaság (Wine Society), the first Hungarian online wine shop, was established in 2000 (

Bortársaság 2022). Since that time, many other (wholesale and retail) wine stores entered the online wine market (namely Borháló, Pinceáron, Veritas, Selection, Borbázis, Borház, Törley, and many wine bars).

At present, the two largest players in the retail market among offline wine shops are Borháló, which owns 45 offline wine shops, and Bortársaság, which operates 25 offline shops and an online wine shop at the national level.

Regarding the content analysis of the 12 most relevant Hungarian online wine shops, two main categories were created based on the price range and potential wine buyers. The first group comprises typical domestic wine sellers that offer wine and alcoholic beverages made in Hungary, such as Borháló and Pinceáron. Their wine prices are moderate, ranging from 1.74 to 143 EUR per bottle. The second group of companies—Törley, Bortársaság, Grape-Vine, Vinotrade, Onlinebor, Selection.hu, Borház and Veritas—sell both Hungarian and imported wines ranging from 1.24 to 1071 EUR.

Today, an online company can measure its success online through SM activity (number of likes or followers), but due to the lack of other relevant data, we assumed that the reputation of the online wine stores is in line with the number of their Facebook and Instagram followers.

Figure 2 presents the number of Facebook and Instagram followers derived from the company’s Facebook profile, which is consistent with the popularity of the wine stores. The top 4 companies enjoyed a significant number of Facebook followers, Törley had 102,637 followers, Bortársaság 52,698, Borháló 29,172, and Pinceáron 22,887 followers. The other shops had fewer than 20,000 followers on 31 January 2022.

5. Empirical Results

This section presents the five market leaders and the statistical analysis of web content of 12 selected online shops.

5.1. Borháló

Borháló is the second largest offline and online wine store in Hungary (also providing a webshop), founded in 2011 and operating as a franchise system (owned by Vinotrend Ltd., Pomáz, Hungary). Its net profit was 74,474 EUR in 2020 and they plan to enter the international market in the future (

EMIS 2022). There are 50 wineries in the Borháló franchise network, most of them are located in Budapest. The company’s wine stock is selected by professional wine experts; skilled owners of each shop choose wines they consider worthy of selling in strategic cooperation with domestic winemakers. Borháló mainly sells Hungarian wines, craft beers, pálinka, and other nonalcoholic beverages. Its wine price range is 2.5 to 97 EUR/bottle (

Borháló 2022). Their main wine products are Irsai Olivér, Olaszrizling, Sauvignon Blanc, Cabernet Sauvignon, and Merlot. They organize wine tastings, online and offline events as marketing techniques to attract the interest of customers. The company is very active online (writing blogs, sending newsletters) and on SM platforms using Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and YouTube. They won the Mastercard Merchant of the Year Award in the best consumer experience category in 2016.

5.2. Bortársaság

Bortársaság (Hungarian Wine Society) is one of the oldest Hungarian wine distributors, founded in 1993. The Wine Society’s business idea was inspired by the Oddbins wine shop in London, UK. In 2020, its net profit reached 447,551 EUR (

EMIS 2022). They opened 25 offline wine shops in Hungary. Their wine stores are located mainly in the shopping centers of the capital city but can also be found in the larger cities, in particular, in Debrecen, Pécs, Győr, Szeged, Kecskemét, and Balatonfüred. Regarding the web content (

Bortársaság 2022), its website is also available in Hungarian and English to attract foreign buyers. Furthermore, they offer Hungarian wine, foreign wine, and other alcoholic beverages. Its wine assortment comprises 507 different items. In addition, they offer champagne, spirits (pálinka), beers, and accessories (e.g., glasses, packaging, delicatessen). Regarding the pricing strategy, its wine prices range from 3.4 EUR/bottle (the cheapest Hungarian wine was the Csanádi Sauvignon Blanc in 2021) to the most expensive wines above 1000 EUR/bottle, the Vega Sicilia Unico 2009 Magnum. In addition to online shopping and marketing tools, the company’s website and Facebook profile also offer various offline wine-related events such as wine tastings, and they frequently participate in different festivals. They offer free home delivery to anywhere in Hungary and provide the possibility of ordering or sending wines within the European Union. Considering its retail networks, Bortársaság also delivers wines for wholesale networks (restaurants, hotels, and wine bars) with the help of its own sales team. Finally, Bortársaság has notable online and SM business activity by writing blogs and sending monthly newsletters and posting on Facebook.

5.3. Pinceáron

Pinceáron is a significant market player in the Hungarian online wine business. Pinceáron’s wines are tested by the executive sommelier (Antal Kovács). The wine shop is operated primarily as a webshop. They have an offline store in the center of Budapest. They offer only Hungarian-made, chemical-free wine (‘wines only from grape’). This is an important part of the company’s marketing strategy and philosophy. The price of wine ranges from 4.9 EUR to 143 EUR. As offline marketing tools, they organize wine tastings, wine dinners, a wine club, and frequently advertise in regional journals. Classical Internet tools (e-mail, newsletter, blogs) are often used for marketing purposes. Furthermore, their SM activities encompass Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and YouTube.

5.4. Veritas

Veritas is one of Hungary’s top wine distributors. The mission of the company is to promote cultural wine consumption in Hungary. The Veritas wine shop was founded in 1995; the company name originates from the Latin proverb: ‘in vino veritas’. They sell Hungarian, European, and New World wines (shipped from New Zealand, Australia, and the USA). Its Hungarian wine prices range from 1.7 EUR (the Hilltop Arany Borcsalád Pinot Noir Rosé 2010) to 857 EUR (the Szent Tamás Esszencia 2013) per bottle, while its most expensive foreign wine costs 600 EUR, the M. Chapoutier Le Pavillon Rouge, and the Ermitage AOC 2009 (

Veritas 2022). They are also commercializing wine, spirits, champagne, sparkling wines, and accessories. Veritas supplies more than 2500 restaurants and retail shops in Hungary. They are buying wines from more than 50 Hungarian and 20 foreign wineries (

Veritas 2017). However, Veritas typically operates as an online wine shop, but it set up three offline stores in Budapest. They offer a virtual tour on their website. Besides standard Internet marketing tools, they use the widest range of SM media platforms, Facebook, Instagram, Pinterest, Twitter, and YouTube channel.

5.5. Törley

According to their website (

Törley 2022), the company has a 130-year history. On 1st August 1882, József Törley registered his business under the name Törley József and Company at the Budapest Commercial Court. The company merged first with Hungaria in 1960 and then with the Hungarovin companies in 1973. The company expanded further with Hungarovin restarting the François winery in 1982, the acquisition of the György-Villa in Budafok in 1986, and a 99% stake in BB in 1995. Including the Törley brand, these brands were part of the Henkell and Söhnlein Hungaria Group from 1997 to 2004. In 2005, Törley Holding was created, with which Walton was merged first in 2010, and then György-Villa, which absorbed the François winery, and Szent István Korona, which was created by the transformation of Hungarovin in 2013. Finally, the Hungarian brand merged with Törley in 2014, which still maintains its leading position in Hungary. The company had the highest number of Facebook followers (102,637). Their prices range from 2.2 to 11.3 EUR offering 50 product items (including champagne, sparkling and still wines).

Table 1 illustrates the result of the web content analysis of the major online wine shops in Hungary reflecting to the elements of the marketing mix and online SM platforms Each element of the marketing mix is divided into the dimensions of product, price, place, and promotion including SM. However, in the beginning of their activity, many of these shops were founded or started their business offline (Törley, Borháló, Bortársaság, and Veritas), and entered the online wine market later.

Overall, result shows that Hungarian online wine sales are concentrated in the largest wine companies (Törley, Bortársaság, Borháló, Veritas, and Pinceáron). Smaller market players chose effective nice market segmentation, namely Pinceáron provides crafted wines (more natural wines), while Veritas promotes cultural wine consumption. Most shops sell Hungarian wines, but the largest companies (Bortársaság, Vinotrade, GRAPE-VINE, and Veritas) also offer a wide selection of imported wines. With online shopping, offline stores are also needed for market success. It emphasizes that personal contact and sales cannot be ignored in the wine business.

Regarding the pricing of the wine shops, Hungarian wine retail prices varied between 1.24–2990 EUR/bottle, while premium imported wines (e.g., French Bordeaux wines) are also available in high-price categories. It indicates that prices of Hungarian wines start at a relatively low level (1.5–2 EUR) and premium wine prices are also lower (560 EUR on average) compared to foreign imported high-quality wines (1500 EUR or more).

Figure 3 shows that there is a clear connection between the profitability of online wine shops and their age. The average age of the companies was 17 years, the youngest was established 3 years ago, while the oldest, as well as the most profitable one, started its business activity 29 years ago. The age of the company may induce more reputation and consumer awareness stimulating profitability.

In Hungary, the most popular classical online marketing tools used are professional blogs and newsletters. In addition, today, SM activity (Facebook, Instagram, Pinterest, Twitter, and YouTube) has become an ordinary part of the communication mix of the Hungarian wine shops. The most popular tool was Facebook in 2022. Unlike the increasing popularity of SM, wine shops also use offline marketing and promotional tools, such as wine tastings, wine dinners, and wine clubs. This indicates that the importance of personal and face-to-face contact in this sector will not disappear. However, the Hungarian online wine business can still be considered as a growing market compared to offline sales, but the potential growth forecasted is limited in the future. At the same time, the offline wine sales growth potential was significantly hampered by the spread of the coronavirus (curfew and border closure, lockdowns, and the breakdown of the HORECA sector). In consequence, due to the pandemic, the Hungarian online wine market has been restructured and developed. However, online shops with expanded retail connections might realize even greater turnover. This may result in the higher importance of the retail sector, e.g., wine tastings may take place in the retail stores or online at the expense of the restaurants in the future. With respect to price and product, higher share of the purchase of low-priced wine category were observed, but in a larger quantity because the wines were bought for their own consumption at home and not as a gift. Wines in the high-price segments were affected the most by the COVID indicating drop of the demand.

Regarding the profitability of the wine shops, Vinotrade accounted for the highest Net Profit (Profit After Tax) in million EUR followed by Törley, Grape-Vine, and Bortársaság companies. This indicates that shops that sell both wholesale and retail are more profitable in the sector (

Figure 4).

The results show that the number of FB followers is correlated with Instagram followers (

Table 2). The higher price range is positively and significantly correlated with the net profit of the wine shops. Therefore, a wide selection of wine may attract more consumers and generate higher amount spent on wines. Furthermore, the age of the companies, the number of Facebook followers, and availability of imported wines are positively associated with profitability; however, these coefficients were not significant. In turn, the number of offline wine shops in Budapest and Instagram followers is negatively correlated with the profit rate (

Table 2). This indicates that operating offline stores requires higher costs, especially in the capital city. Consumers living in the capital city can easily access offline wine shops and a wide range of wine products. The operation of offline shops in other cities may provide a higher profit rate with lower costs.

6. Conclusions

The rapid growth of the Internet coverage and e-commerce is also affecting the wine business. Studies show that overseas countries put more emphasis on reaching new clients and communicating more with their customers on the different SM platforms, but today, European wineries also use SM platforms more frequently.

Despite the importance of the topic, the impact of online marketing and SM usage on the profitability of Hungarian wine shops has been quite understudied. This article analyzed the marketing activity of the most relevant Hungarian online wine shops, focusing on the use of online marketing tools, social media, and its impact on profitability. Qualitative data collection techniques, such as web content analysis and statistical analysis, were applied with the twelve most important market players in the online wine business. The results suggest that the Hungarian online marketing activity of wine shops became important not only for the largest ones (Törley, Borháló, and Bortársaság) but also for the smaller market players (Pinceáron and Veritas).

Regarding products of 4P, the smaller Hungarian online wine shops sell mainly domestic wines, but the largest companies also offer a wide range of imported wines. Furthermore, operating offline stores are also significant factors in market success. This emphasizes that personal sales cannot be neglected in the Hungarian online wine business (Place). Regarding the pricing of wine shops (Price), wine retail prices range between 1.14 and 2990 EUR/bottle on average, while premium imported wines can be sold in higher price categories (800–1000 EUR) compared to domestic ones.

Addressing to Promotion, behind classical Internet tools (homepage, blogs, newsletters), SM activities (Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, Pinterest, and YouTube) became an essential part of the communication mix of the Hungarian online wine business, especially to target younger generation of buyers (30%). In contrast to the increasing popularity of SM, wine shops also use offline marketing and promotional tools such as wine tastings, wine dinners, picnics, and wine clubs, indicating that personal face-to-face contact is still important in this sector, especially to keep contact with older generation buyers. In conclusion, both online and offline marketing techniques are widely used by Hungarian wine shops. But it should be mentioned that only a limited share of older generations (5%) can be reached by online marketing activities revealed by previous studies.

Regarding profitability, wine shops that sold their products both wholesale and retail and at higher price range were more profitable in the sector, since the higher price range was positively and significantly correlated with the net profit (profit after taxes). Furthermore, the age of the companies, the number of Facebook followers, and imported wines are also positively associated with profitability; however, these coefficients were not significant. It seems that more diversified strategies (e.g., both wholesale and retail, online and offline, a wider range of products including foreign wines) contribute to higher profits. In contrast to this, high number of offline shops in Budapest and the number of Instagram followers were negatively correlated with the profit rate. This may be explained by the fact that Instagram users belong to the younger generation than Facebook users, consuming other alcoholic beverages and less wine.

Finally, although the Hungarian online wine business can still be considered a growing market, because of the declining demand, the potential growth is expected to be moderate in the future. The sales of offline shops were significantly hindered by the coronavirus, especially in rural regions. In turn, online shops with strong retail connections were better off, and this may lead to the restructuring of the wine sector where the retail pillar becomes more important. A significantly higher demand for cheaper products was observed since the wine was purchased for own consumption.

Regarding managerial implications, online wine shops should focus more on social media activity in the future, by spending more on Facebook and Instagram media campaigns and maintaining some offline marketing tools (tasting, participation in wine events) at the same time to keep contact with older consumer segments.

The limitation of the research is that it focuses on the main market players of online wine shops in Hungary, not including sales at wine cellars or other distribution channels. The research was realized on 31st January 2022. The main source of this research was obtained from the companies’ homepages and financial reports. Further research may focus on the deeper financial analysis of the Hungarian online wine business, as well as the consumer segmentation of the wine purchased online.