1. Introduction

Ho Chi Minh City (HCMC) and Binh Duong Province (BDP) are two metropolitan areas in the South East region of Vietnam; which have attracted a number of people from all over the country to come here for living, working, and studying; these two cities also became the first two epicenters for the fourth outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic. Migrant workers play an essential role in the labor market for big cities; however, they are also the most vulnerable population and struggle to access social welfare, especially during this pandemic. Based on the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) held in Vietnam in 2017, participating countries aimed to achieve comprehensive economic growth by 2030, which implies that there will be no one left behind, the benefit of this economic growth will be enjoyed by the disadvantaged. Its achievement will generally be distributed equally to the target groups or economic sectors (

Bui 2020;

Oxfam 2017). Therefore, it is necessary to explore the problems of these vulnerable populations, especially migrant workers, and suggest policies to ensure social equity.

Vietnam faced two major pandemic outbreaks in 2020 and 2021, the Vietnamese government implemented strict social distancing regulations according to Directive 16 and spent a significant budget to implement a support package of up to USD 2.6 billion in 2020 and continue to support in 2021. These packages from the Vietnamese government aimed to ensure social security, quickly and timely provide support with the motto “no one was left behind”, therefore the beneficiaries in these public expenditure programs were the poor and the unemployed who were vulnerable populations. The government decided to support them in kind and in cash by opening the food reserve, using the social insurance fund and the state budget. However, these programs were ineffective due to the low coverage level, limited budget, and discriminatory regulations on residence registration.

During the pandemic in Ho Chi Minh City and Binh Duong Province, residents stayed at home, employees worked and stayed at the workplace, and a large number of workers and self-employed workers lost their jobs. The vulnerable had a low income and did not have any savings. They relied on assistance from the private sector such as food, daily appliance, and little money, to survive for several days but not to cover rental costs, therefore they hoped to return to their hometown. Businesses, researchers, and policy makers worried about the labor shortage while wishing for a quick economic recovery after the pandemic. In this urgent situation, the government immediately set up and spent three support packages with a total budget of over VND 15,000 billion in nearly a couple of months. The first and second packages with half of the budget were for supporting self-employed workers and workers without a signed labor contract, but these beneficiaries were required to be permanent residents and to have household registration. Due to their previous characteristics, many migrants could not meet this condition so they were unable to receive support packages yet or have not received an adequate amount to sustain their daily life while the social distancing policy is prolonged. In contrast, there were announcements regarding the following support packages and coverage extensions; migrants were unable to wait to receive those packages which resulted in them returning to their respective hometowns to ensure their safety and security, including those who have lived in the aforementioned metropolitan areas for many years. From residents’ feedback and indignation, the third package was set up for all residents and did not have any requirements and no discrimination based on household registration, so some of the residents who had received from two previous packages, children and workers who were working and having salary continued to receive from the third package. This regulation was in cash but not fair to labor groups because some residents received once whereas the others received twice or three times, and some workers who were not disadvantaged gained support, so the money which each beneficiary received was too little, they could only buy food for a few days but not cover other living expenses. In that circumstance, migrants felt vulnerable and unfair that they were the major labor and contributed to the development of the cities, but were discriminated against when falling into difficulties in daily life. The big cities faced the wave of migrant workers’ repatriation. These cities faced a dilemma: keep the workers staying with “Shelter in place” or facilitate workers to “Go back to where you came from”. If migrant workers remain in the big city, supporting package coverage will remain to be inadequate. On the other hand, if migrant workers return home, there will be a temporary labor shortage, affecting the expectation for a quick economic recovery after the pandemic. The problems above showed that the government was spending the budget immoderately and using resources inefficiently, struggling with labor issues while desiring to retain and attract workers for economic recovery. The government only encouraged workers to return but did not provide specific support while they were distrusting of support. For that reason, besides solutions to resolve the pandemic, strategies to recover the labor market post-pandemic period are necessary. The objective of this study is to shed light on an evidence-based platform for interventions of government in both the short term and long term with the aim of attracting workers to return and quickly adapt to the economic recovery process.

Originating from

Hajighasemi and Oghazi’s (

2021) idea, their study showed the income gap and suggested pushing the integration of labor rapidly to make a positive contribution to the economy after the outbreak. In addition,

Gill and Shaeye (

2021) used data on income collected from the previous great economic recession to illustrate the income difference in gender and forecasted the gap after the pandemic. Besides

He et al. (

2021),

Liebert (

2020), and

Narula (

2020) implied that workers’ difficulties and vulnerability during the pandemic were consequences of the inefficiency of social policies and income differences, so incentives for income integration were recommended for recovery after economic crises. To the best of our knowledge, there are no studies in Vietnam regarding income integration. Income is an indicator reflecting equity of income distribution, income disparity is also a facet showing inequity in society, income integration is reducing these gaps. Approaching their arguments, we argued that the improvement of workers’ income is beneficial to enhance the quality of life, to have savings, and overcome shocks by themselves, we expected the government to stop temporary solutions and overspending and to focus on sustainable solutions related to improving income.

Generally, the study had two goals. First, the study drew experience for similar cases in the future, so demonstrated that support packages were inefficient and those were not what workers really need as support, this demonstration provided recommendations for short-term solutions. Second, the study gave sustainable suggestions for the government to meet workers’ needs, so determined impact factors on their income, from this result, provided recommendations for long-term solutions. We are motivated to identify the factors driving the process of worker integration with the argument: if migrant workers are better assimilated and adapted to the urban environment then the faster the economy recovers after returning to a new normal status. From estimating the model by the method of ordinary least square, the study used data of 614 observations investigating the immigrant and local workers in 2019 to indicate integration factors that impact the income of labor working in HCMC and BDP during normal conditions. In connection to the assessment of discretionary public policies to protect society based on additional descriptive data of 190 observations investigated in September 2021, we suggest draft policies to support migrant workers remaining in these areas to continue to stay, incentivize migrant workers who have returned home to quickly come back to the big city, and help adapt to the urban environment under the new normalcy in the long term.

The study was organized as follows. It was continued with the presentation of literature related to equity and the government’s role, income and integration with the consideration of the government’s role. The next section describes data used to express the government assistance and worker performance, and the methodology used to analyze data. Then the results are presented and analyzed based on empirical data with a regression model, this also includes a discussion on outcomes. The final section has conclusions and policy implications, and limitations are also drawn.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Equity and Role of Government

The role of the government in the economy is related to market failure and unfair income distribution. Even if the economy is Pareto efficient, the government intervenes in the economy and society to ensure equity. In a free-market economy, the income distribution of an individual receiving from the market depends on the resources that one possesses, such as human resources. The distribution also depends on other factors, such as economic–political fluctuation, discrimination, natural disasters, and pandemic. The distribution can be efficient; however, the resources possessed by each individual are different, together with other factors. As a consequence, the initial income that an individual receives is different from others. It is considered an unequal income distribution so the government has a role in redistributing to alleviate poverty and ensure equity (

Stiglitz and Rosengard 2015).

The government plays a vital role in redistribution to ensure social equity, economic efficiency, equity, and efficiency, which are the two highest objectives for social and economic growth and development. According to

Kuznets (

1955),

Banerjee and Duflo (

2003) argued that social inequity and economic growth have an inverted U-shaped relationship. They had demonstrated that when the social inequity is at a low level, the inequity increase is acceptable in economic growth. However, when it is too high and exceeds a certain threshold, it will reduce economic growth (

Banerjee and Duflo 2003). However, redistribution ensuring social equity will not increase the total social wealth but raise total social welfare as Mill’s utilitarian (1861) (

Habibi 2001). In addition, redistribution will help motivate the poor, relieve their dissatisfaction and suspicion toward the government, and reduce social crimes, thereby helping create a positive externality (

Stiglitz and Rosengard 2015).

In order to create incentives for policy beneficiaries and achieve social equity’s objective, the government redistributes through a tax and subsidy system. The government also uses a social insurance system and provides goods and services through state enterprises or public–private partnerships. In some exceptional cases such as disasters or pandemics, some groups of individuals will fall into poverty and become highly vulnerable; thus the government also ensures equity and reduces vulnerability by using some tools such as national reserves, temporary compensation, hardship allowances in cash or in kind to mitigate the negative impacts from shocks (

Stiglitz and Rosengard 2015).

In the era of COVID-19, most studies concentrated on the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on health care, the economy, and society, thereby recommending solutions. Some studies are interested in the efficiency or effectiveness of the government’s support or reliefs as the fiscal and monetary policy to recover the economy. However, not many studies focus on social policy with the aim of stabling society. In countries with many external migrants such as the United States, the government has enforcement actions, immigrant detentions, and deportations (

Miller et al. 2020). On the contrary, in countries with a significant number of internal migrants such as Vietnam or China, the government faces a substantial degree of remigration to rural areas and a considerable lack of workers in urban areas so it enforces support relief. Many studies expressed that migrants are severely affected by the socio-economic impacts and fall into unemployment, hunger, and exclusion (

Das 2020;

Fang et al. 2020;

Gill and Shaeye 2021;

Debucquet et al. 2020;

Narula 2020), these studies also described the effectiveness of public policies (

Das 2020;

Narula 2020). The most common types of social policies in some countries are food aid and cash transfer, wage support, food price controls, utility bill support, unemployment benefits, mandated grace period for utility bills; and they tend to support urban areas and informal sectors because of considerable fluctuation and vulnerability. However, in some places, it is impossible to avoid residents’ backlash due to reasons such as: not receiving promised food support, not being eligible for food support or receiving food support in adequate quality and quantity. The acquired meaningful support is food and utility support, then cash transfer, school fee, and consumption subsidy (

Fang et al. 2020). It showed that the people’s top desire is also the government’s top priority, but utility support is not a priority even if the government regulates it.

The informal sectors in the urban areas that exist self-employed, casual and contracted workers, or small-scale entrepreneurs are critical and consist of nearly 60–80% of economic activities, but half of those are the precarious poor dwelling in high-density places with sanitary and health conditions, depending on employment of the modern economy (

Lewis 1954;

Narula 2020). The vulnerability and precariousness from the shock of the pandemic bring challenges and opportunities for policymakers (

Narula 2020). The government provides rescue packages that put a financial burden on the country and which are unable to cover all both formal and informal sectors due to unmeasurable and invisible forces (

Narula 2020;

Stiglitz et al. 2019). However, the government also realizes its less effective intervention exists for a long time (

He et al. 2021;

Narula 2020;

Pazhanisamy 2020). This case in which people are strongly impacted by the shock and also vulnerable before, emergency support packages are provided for people not covered by the regular social programs, and the regular social programs are also extended reflect the consequence of pre-existing persistent inequity and ineffective social policy (

Béland et al. 2021;

He et al. 2021); the prior information of lockdown leads to market failure regarding demand and supply of goods, residents’ behavior related to return or remigration (

Pazhanisamy 2020); most residents in the informal sectors are unable to access the public goods and services, public policy and social security during lockdown (

Narula 2020); the lack of integration programs for immigrants in the normal status such as training medical professionals in the United States leads to a large quantity of non-employed immigrants as health workers and a severe labor shortage in health care in the pandemic (

Liebert 2020); both the poor living condition and poor acculturation of immigrants cause the higher rate of death in immigrants than that of natives (

Aradhya et al. 2020).

Researchers suggest the government focus on economic recovery rather than infrastructure development such as roads, telecommunications, transport, and other public utilities; to carry out relief, pump-priming, and to provide loans without expectation of returns (

Pazhanisamy 2020); to maximize the immigrants’ human capital through effective integration programs, which is beneficial to the economy and the society of destination (

Liebert 2020). Using the income data around the 2007–2009 Great Recession to analyze the income difference between immigrants and natives,

Gill and Shaeye (

2021) inform that the gap after the current downturn is less than before or during the recession.

Xie and Zhou (

2014);

He et al. (

2021) imply that the equity is more than before the crisis. Both

Gill and Shaeye (

2021),

Che et al. (

2020),

He et al. (

2021),

Wang et al. (

2021) agree that there exists an income gap or a differential influence relative to the education and skill of immigrants. From the studies related to a pandemic or economic crisis, most of the researchers as

Han and Kwon (

2020),

Häusermann et al. (

2014),

Rehm (

2009),

Thewissen and Rueda (

2017) suggest that the government should come up with consumption subsidy in the short term, but undertake in education and training in the long term. However, the government in some countries, such as Vietnam or China, urges migrants to return and contribute to the economic recovery. Experts recommend that migrants return by themselves, and enterprises need to increase wages even if most businesses face financial difficulties. There are limited studies that pay attention to education, training, or living condition after the pandemic, yet these are the aspects of integration.

2.2. Income and Integration

Integration means being able to adapt to life (

Berry 1994,

1997;

Gordon 1964;

Phillimore 2012;

Qiu et al. 2011;

Ren and Folmer 2016), is pushed up by the expectations as incentives (

Ager and Strang 2004,

2008). If the integration process is good, or in other words, that is maximizing the utility, the residents may intend to stay in some places (

Dustmann and Gorlach 2016). For migrants, their expectations in a destination are argued as expected income (

Harris and Todaro 1970;

Huynh 2012;

Sjaastad 1962), compensation for deficiencies (

Stark and Bloom 1985), quality of life in terms of education, health, and living environment (

Nguyen 2018). Migrants are identified as the most vulnerable population in large cities. The initial income they receive from the market distribution has a big gap compared to locals. The income gap is considered as income integration, economic integration, or difference in economic integration.

Along with cultural integration and welfare integration, economic integration is one of the three forms of life integration.

Chiswick (

1978) was the pioneer in the experimental study on the wage convergence between migrant workers and local workers, unified this convergence as economic integration and called it income integration or integration in the labor market.

Borjas (

1985,

2014) argued that economic integration is the convergence of employment opportunities and income between migrant workers and local workers over time. It was assessed by comparison. In general, economic integration is considered a gradual decrease in differences in employment opportunities and income differentials between compared groups. In addition, the expectations of migrant workers are a quality of life that will be guaranteed and gradually improved over time (

Liebert 2020;

Pazhanisamy 2020). Therefore economic integration is seen as progressively reducing material disparities such as income, working conditions, or working environment (

Stiglitz et al. 2010). Specifically,

Stiglitz et al. (

2010),

Ryabichenko and Lebedeva (

2016),

Tvaronavičienė et al. (

2021) scrutinized them by life satisfaction. New Economics

Foundation (

2015) stated that economic integration depends on income, social environment, knowledge of an individual, cultural activities, and recreation activities.

According to the income function of

Mincer (

1974),

Chiswick (

1978) described the income status of migrant workers by the regression function:

here

is the salary of person

l,

is the set of social-economic characteristics of person

l,

is the set of age and number of years of experience of person

1,

is the dummy variable, with

= 1 for the migrant workers, and

= 0 for local workers,

is the amount of time workers have been living in the place of migration, and

= 0 if it is a local labor force,

is the migrant workers’ ability to do the income integration, and

is the rate of the income integration of migrant workers. The results showed that the income of migrant workers was 16–24% lower than that of local workers, but it would be improved after 8–25 years, and the income of the former migrant workers will be higher than that of new migrant laborers and will be higher in the future (

Borjas 2014).

In contrast,

Borjas (

1985) stated that

Chiswick (

1978) using the income of previous migrant workers to predict the income of new migrant laborers was not valid. As income integration was also affected by age or a group of the migrant population known as the group effect (

Borjas 2014, p. 42).

Borjas (

1985) described the economic integration of migrant workers using a regression function:

here

is the total impact by degree and speed of integration. The results of Borjas were almost similar to the above results. Therefore Borjas believed that the integration ability of migrant workers was not correlated with human capital accumulation, and there was a significant change in the skills of migrant workers with the assumption

. Meanwhile, there was a difference and interweaving of skills between migrant workers and local workers in reality. (

Borjas 2014, p. 48). However, in the experimental studies of

Jimenez (

2011) and

Liebert (

2020), integration is a process of inclusion of newcomers in the destination and the internal cohesion of the societies affected by immigrants. Effective integration is to ensure immigrants are able to maximize their human capital.

Friedberg and Hunt (

1995) argued that Borjas ignored the critical factor of workers’ age at arrival so demonstrated differences in economic integration by migrant population, place of birth, year of survey, age at arrival as by the model:

here

is the age at migration,

;

YSM is the amount of time since laborers migrated to work. Furthermore,

LaLonde and Topel (

1992) suggested that this difference exists because of the concept of economic integration. They said that economic integration occurred if someone had lived for a long time in the migrant area, and they would have a higher income

in the above model, so LaLonde and Topel also recommended comparing the difference between migrant and local labor groups would be more optimal.

Empirical studies in recent years measured economic integration by income and employment, in which significant factors are personal characteristics (gender, age, place of birth, education, marital status), family characteristics (household size, shocks), migration characteristics (year of migration, migration length, city or municipality), employment characteristics (frequency of change, nature, type, contract, psychology), human capital (years of schooling and experience), social capital (support from relatives and friends), urban spatial structure (

Huynh 2011,

2012;

Korpi and Clark 2017;

Liu 2021;

Nguyen et al. 2013;

Nguyen 2016;

Zhang and Meng 2007). However, some studies are flawed when they did not fully consider aspects of life or economic integration (

Huynh 2011,

2012), or limits on index calculation (

Nguyen et al. 2013), and scope of the study (

Nguyen 2016). In addition, some conclusions were contradictory and contrary to the actual trend or fundamental theory.

Zhang and Meng (

2007) argued that the human capital impacting negatively economic integration was contrary to

Chiswick (

1978),

Borjas (

1985,

2014),

Gill and Shaeye (

2021),

Jimenez (

2011),

Liebert (

2020).

Zhang and Meng (

2007) also concluded that destinations such as cities or urban areas adversely impact economic integration was contrary to

Korpi and Clark (

2017) or

Nguyen et al. (

2013). At the same time, some studies in Vietnam have some contradictions about the independent and dependent variables,

Nguyen (

2019) measured aspects of life as independent factors, but

Nguyen et al. (

2013) considered those as dependent factors. Moreover, from our best understanding, there is almost no Vietnamese study about the interaction between economic integration and financial capital or human capital, social capital, or production capital that was studied by

Alba and Nee (

2003),

Gordon (

1964), and no study about the relationship of economic integration and welfare integration as

Borjas (

1999), or interaction of economic—welfare—social integration as

Depalo et al. (

2006).

During the COVID-19 crisis, economic integration is mentioned as income and social welfare differentials between immigrants and natives. Researchers do not pay much attention to this topic (

Gill and Shaeye 2021) to demonstrate inequity in cities and clarify the extreme consequences of impacts, then give recommendations in terms of social policies. To the best of our knowledge, Vietnam follows the trend of the other countries, but there is no study on this matter. Besides the points listed in 2.1, other studies stated that the public budget’s burden for redistribution does not depend on the level of immigration but turns on the effectiveness of integration policy, inclusion in the labor market, and immigrants’ outcomes accounted as integration in the labor market and integration swiftness (

Burgoon 2014;

Hajighasemi and Oghazi 2021). These studies propose that it is necessary to facilitate integration by participating in the labor market, and accumulate integration by attaining health, housing, and education (

Bakker et al. 2017;

Hajighasemi and Oghazi 2021;

Hansen et al. 2017;

Ruist 2014).

Generally, migrants are the main labor in the urban setting however they are a vulnerable population. It is important to have relief from the government to reduce vulnerability caused by shocks, but these rescues are only effective temporarily. We need to think about support to help them overcome shocks by themselves in the future, adapt promptly after pandemics, and adapt sustainably. Those are solutions to promote them to integrate the urban life and improve their income. As a result, they will be well equipped to contribute better to the economy, as argued by

Hajighasemi and Oghazi (

2021),

He et al. (

2021),

Liebert (

2020), and

Narula (

2020). Approaching the idea of

Hajighasemi and Oghazi (

2021) about bringing incentives to economic recovery by enhancing the rapid integration of workers; integration perspective of

Ager and Strang (

2004,

2008),

Chiswick (

1978) and

Borjas (

1985,

2014); impacts of income difference of

Gill and Shaeye (

2021), in this study we shed light on the effectiveness of support packages and observe the effects of explanatory factors on integration as income. We asked the following research questions: How satisfied are workers with the relief from the government to adapt to the COVID-19 era in the short term? What factors do impact the income of workers? How to mitigate income in the process of integration into society in the long term?

3. Data and Methodology

With the intention of suggesting social policies, the study conducted a two-pronged analysis: (1) describing the effectiveness of discretionary social policies, (2) identifying impact factors of labor income, and then estimating income convergence as the basis for long-term policies recommendations. For the former, the study used the descriptive method from a survey data of 190 residents in September 2021 via email due to the lockdown situation. Respondents were asked to access social security packages’ effectiveness and present their expectations from the support packages with a 5-point Likert scale. For the latter, the study used a data set surveyed by directly asking 614 respondents, including 380 migrant workers and 234 local workers in HCMC and BDP, based on the questionnaire tested with 78 questions and revised to 58 questions in 2019.

Based on perspective of

Dustman and Gorlach (

2016), respondents in this study were people who were born outside of HCMC and BDP, and who lived in that place for at least one month. HCMC and BDP are two big cities situated in the Southeast region (SR) of Vietnam. The SR which consists of 6 to 9 provinces belonging to the southern key economic region, is considered the leading economic driving force for development in the whole country, therefore it is an ideal place to live, study, and work. With a population rate of 18% of Vietnam and the highest urbanization rate at 60%, the SR is the unique region having a positive net migration rate (9.9%), and the highest rates in this region are HCMC and BDP, 6.1% and 47.9%, respectively. Migrants are an important component of the labor force in these cities, however, they are too young and their professional qualifications are limited. The reports of the General Statistic Office showed that young migrants are increasing gradually, the age of 15–39 accounts for 82.3% of the 15–59 group, and it is 76% of the age of 15–34. Therefore, respondents were aged from 23 years old which was the average age of graduating and formally joining the labor market.

The sample was firstly distributed by the proportion of concentration of migrants in each district, then a random sample was taken and relatively controlled by gender, age, education, and length of time lived in the province to conduct the survey.

The number of samples is distributed as in

Table 1:

The offered model is:

where

is the logarithm of the average monthly income of the worker.

denotes the characteristics of demographic.

denotes the characteristics of migration.

denotes the characteristics of employment.

denotes the characteristics of urban utility (

Appendix A).

Ordinary least squares multiple regression was applied to estimate the association between factor variables and result variables as in Model (4), and this study relies on the hypotheses to test those relations. The study expects that the income of migrant workers is lower than that of local workers (H16−), and then the income will be higher if:

- -

Demographic characteristics: this worker is a male (H1+), is older, and increases to a certain age (H2+, H3–); has a higher education level shown by degrees and has additional certificates, has a higher number of years of experience (H4,5,6+);

- -

Migration characteristics: he has lived for a longer time in the migrant place (H7+), and belongs to the recent group of migrants (H8,9,10,11,12,13+); owns the house, has a permanent household registration book (H14,15+);

- -

Employment characteristics: he joins a better labor market if working outside the public sector (H17−), being self-employed, signing a labor contract, having social insurance (H18,19,20+);

- -

Access to urban utility: he integrates well into the labor market, welfare, and society (H21,22,23+); accesses well to the labor market and social welfare in parallel, accesses society well at the same time with efforts to stay for a long time in the destination (H24,25+).

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Effectiveness of Supports in the COVID-19—Short-Term Policies

To ensure equity and temporarily reduce negative impact, the government used tools such as national reserves, subsidies by finance or essential supplies, and temporary compensation. On 12 August the government signed the decision to utilize goods from national reserves to assist disease prevention operations in both HCMC and BDP swiftly. On 20 August, the government continued to sign the decision to export 130,000 tons of rice without receivables to help citizens in 24 regions. The government also operated urgent subsidies such as “health care for confirmed cases at home”, food packages for preventing residents from starving, with a cumulative value of VND 26 trillion. Alongside direct financial assistance, the government also provided support packages of essential goods that can be used for up to 5 to 7 days. Moreover, most recently, the government has agreed to use VND 30 trillion from the unemployment insurance budget for employees and employers affected by COVID-19 and is drafting long-term policies that will assist orphans and the elderly.

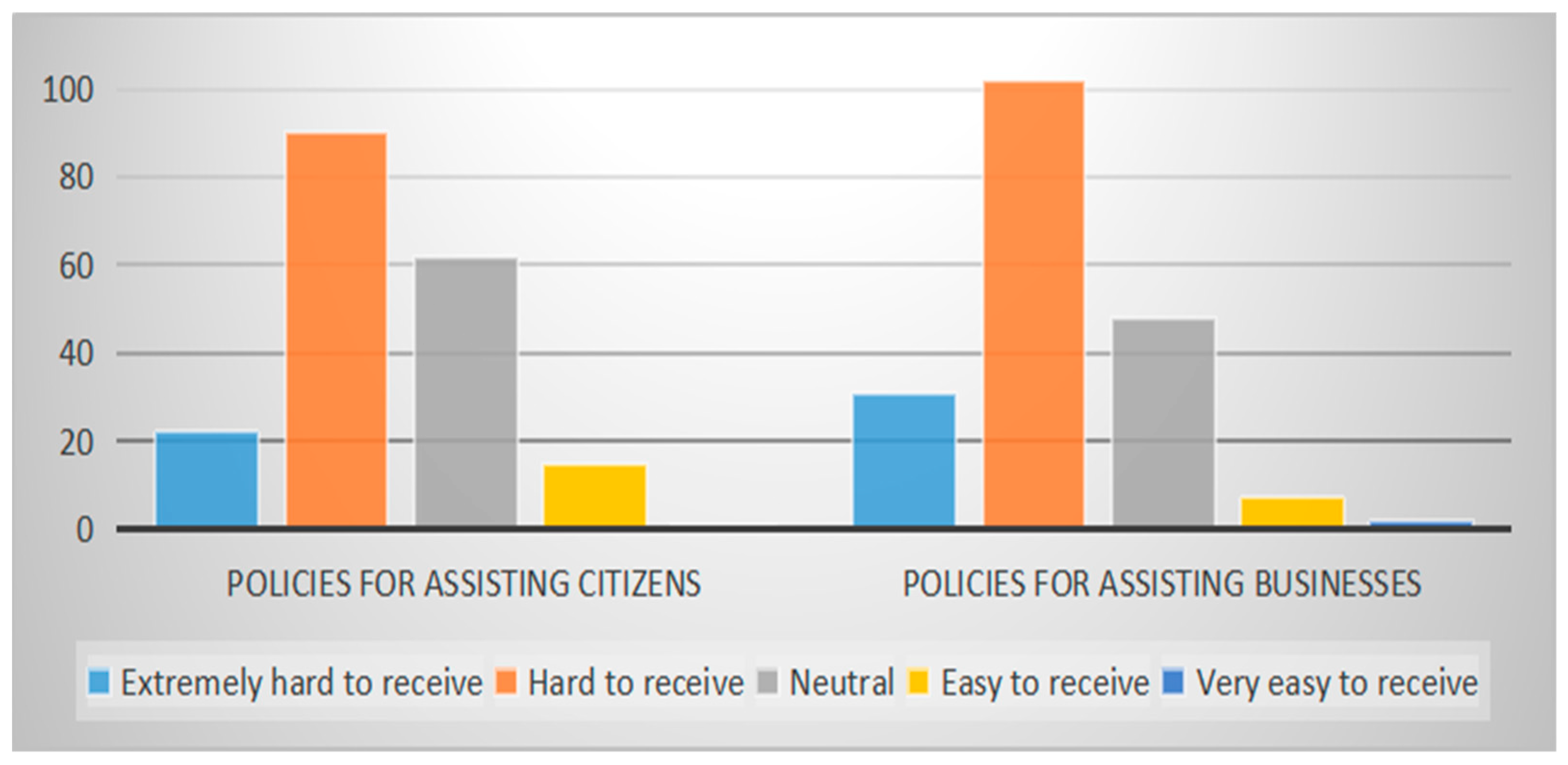

However, the result from the first survey showed that 59% of the respondents claimed that “approaching policies of assisting citizens” is not easy to access. Similarly, 70% of respondents claimed that “approaching policies of assisting business” is not easy to access. (

Figure 1). The assessment is consistent with statements in the research of

Narula (

2020) and

Stiglitz et al. (

2019). These packages were only aimed at groups in the regular social security programs but not really extended to groups outside the regular programs although they were also facing many difficulties initiating from the fourth outbreak. Primarily, only less than 8.5% and 4.2% claim that policies of assisting both citizens and businesses are effective (

Figure 2).

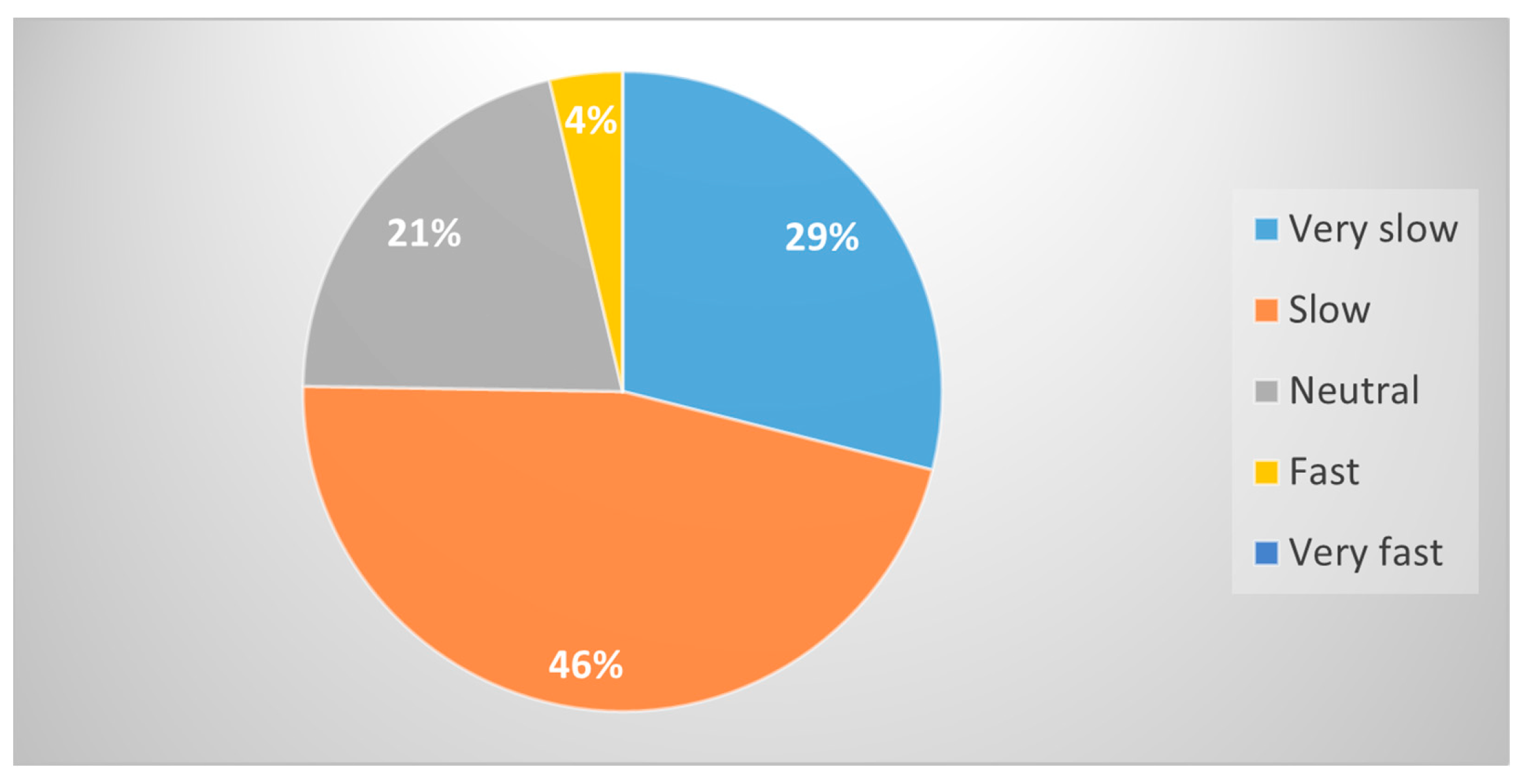

When explicitly asked about the details of assistance, 43% of responders said reducing utility fees, and direct aid to local relief programs that are currently being is most effective; however, the majority are in favor of lowering the banking interest rates and taking out the loans for employees’ salaries with approximately 50% of respondents. Furthermore, when asked about the reliefs, 75% of respondents claimed the disbursement of the subsidies is slow and languid (

Figure 3).

This result partially explained the leave of tens of thousands of migrants as soon as reducing social isolation from 1st October and even hearing about the third fiscal package. This situation looks like the description of other countries in the studies of

Béland et al. (

2021),

He et al. (

2021),

Pazhanisamy (

2020). In the third cash transfer package, the government is ready to run a transfer measure that covers more affected residents by supporting both workers and dependents, including the elderly and children VND 1 million per person, and which also spends from the fund of social insurance to subsidy for both employed and unemployed. As a consequence of ineffectiveness and low coverage of the previous assistance in cash or in kind, they are not capable of waiting and receiving support while they cannot afford food, housing, utility fees, and loans so they move by driving a motorcycle or walking thousands of kilometers. This situation has led to a break in the production chain, and so far, many businesses have not been able to restore production.

4.2. Impacted Factors of Labor Income—The Basis for Long-Term Policies

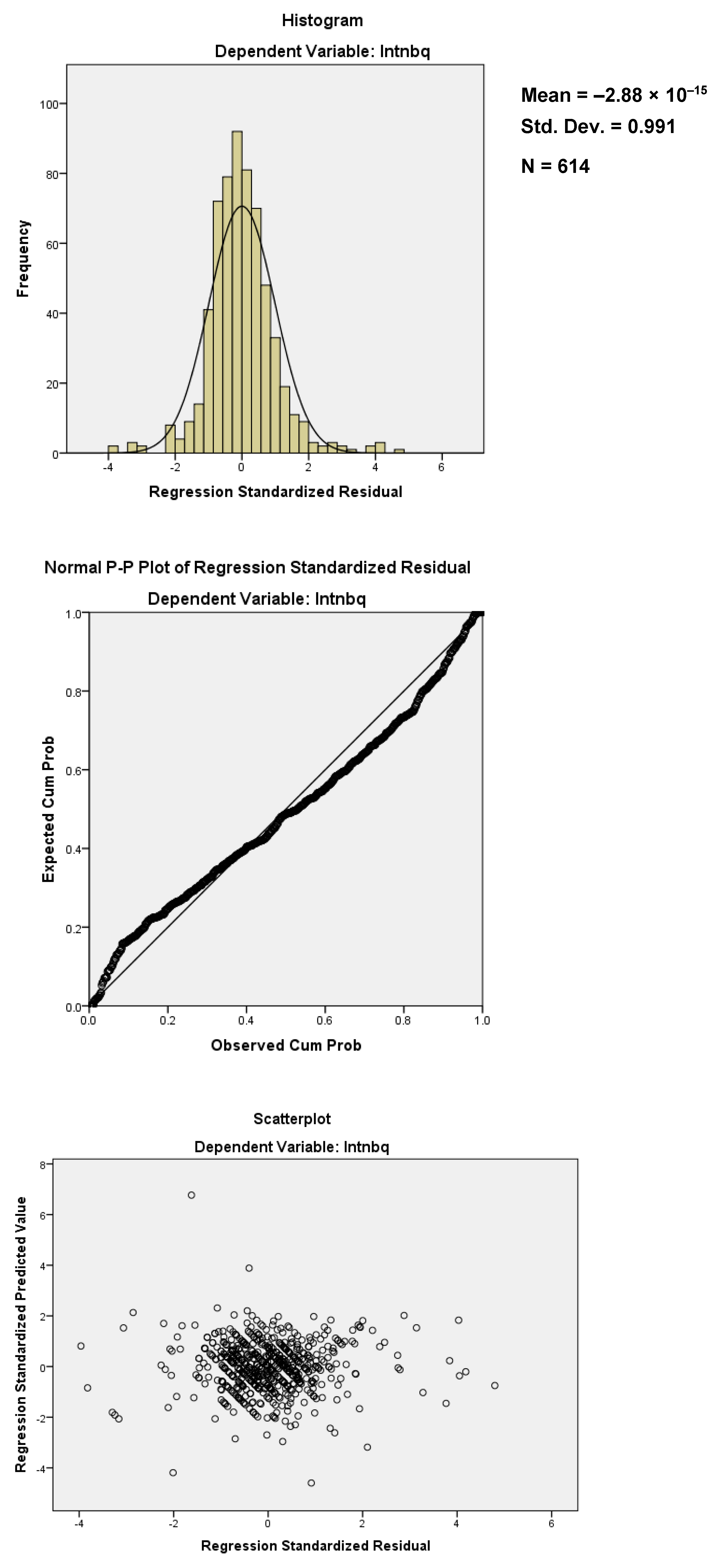

Table 2 reports the results of estimates from the income.

p Values for F statistics indicate that estimates fit well overall. Testing for multicollinearity (except for age and age

2) and autocorrelation show that there is no multicollinearity and autocorrelation, so the regression model complies with the econometric assumptions. Moreover, the normality test, the normal P-P plot, and the linear relationship test show that the normality and the linear relationship do not violate the econometric assumptions (

Figure A1).

As expected, variables are significant factors of income with the exception of the certificate (cer), experience (exp), migration since 1990, 2000, 2005 (year30,20,15), contract (contract), access to welfare, and to the labor market with welfare (acwefa, aclawe). However, the effect of migration since 1995 (year25) is contrary to initial expectations, and it impacts income negatively. Aside from that result, most of the variables consisted of gender, age, age2, education (gen, age, age2, edu) in the demographic characteristics; years of migration, migration since 1995, homeownership (year, year25, howner) in the migration characteristics; work sector, self-employed, insurance (wosec, seemp, insur) in the employment characteristics; access to the labor market with welfare (aclawe) in the access to urban utility are respective to income at all level of significance. Primarily, education (edu), homeownership (howner), work sector (wosec), self-employed (seemp) are the most critical factors impacting income.

4.2.1. Demographic

Variables, namely “age”, “age

2”, “edu”, “cer” and “exp” measure the human capital accumulation. The variables “age”, “age

2” show that the older the workers are, the higher their income is. However, as workers grow much older, their income will start to decrease. With concerns about labor shortage after the outbreak, this estimate shows that along with the trend of new immigrants being young and inexperienced, returning migrants tend to be younger age, the long-term older migrants tend not to return because it is difficult for them to earn a higher salary if returning, they have already accumulated a significant amount of human capital making them easy to find a job in their hometown. Additionally, there is also a rise in repatriation. However, the insignificant variables consisting of additional certificate “cer” and experience “exp” show that there is no income difference. This estimate is consistent with big cities in the South such as HCMC and BDP where all things are favorable, and workers can choose any job at any wage without any requirement, so additional certificate or experience is not necessary. This impact of accumulated human capital measured by additional certifications and years of experience can be expressed by age or education (

Chiswick 1978;

Mincer 1974;

Rodriguez and Loomis 2007). The variable “edu” shows whether there is a difference in income between workers with or without a degree. The income of workers having degrees will be higher. This estimate is also consistent with the arguments of

Bakker et al. (

2017),

Che et al. (

2020),

Gill and Shaeye (

2021),

Hajighasemi and Oghazi (

2021),

Hansen et al. (

2017),

He et al. (

2021),

Ruist (

2014),

Wang et al. (

2021); and suggestions of

Han and Kwon (

2020),

Häusermann et al. (

2014),

Rehm (

2009),

Thewissen and Rueda (

2017).

4.2.2. Migration

When comparing migrants to local workers, “mig” is not significant at the level of 5% but significant at the level of 10%, it shows that there exists an income gap indicating migrants’ lower income and ability to integrate into the urban economy (

, H

16−). This result is consistent with the concepts of

Chiswick (

1978) and

Borjas (

2014) on the income and economic integration of migrants and also with the arguments of

Lewis (

1954) and

Narula (

2020). In addition, “howner” and “reg” show an income differential between workers whether they have homeowners or permanent household registration book, their income will be higher if they have one of those (

,

, H

14,15+), this is consistent with the concept of “a stable life” and increase the chance of getting jobs and accessing to utilities such as education, health care, housing. However, the survey shows that the rate of migrants who have the homeowner and permanent household registration books are only 20.3% and 54.2%, respectively. Under the fourth outbreak’s awful influence with strong containment measures, the first and second inadequate and discriminate reliefs, many migrants could not receive the transferred cash as they need to help, some of them are unable to access the support due to without household registration. Therefore they dismiss the third cash transfer package and leave the city. Most of them will be unlikely to return unless policies clearly support low-income migrants.

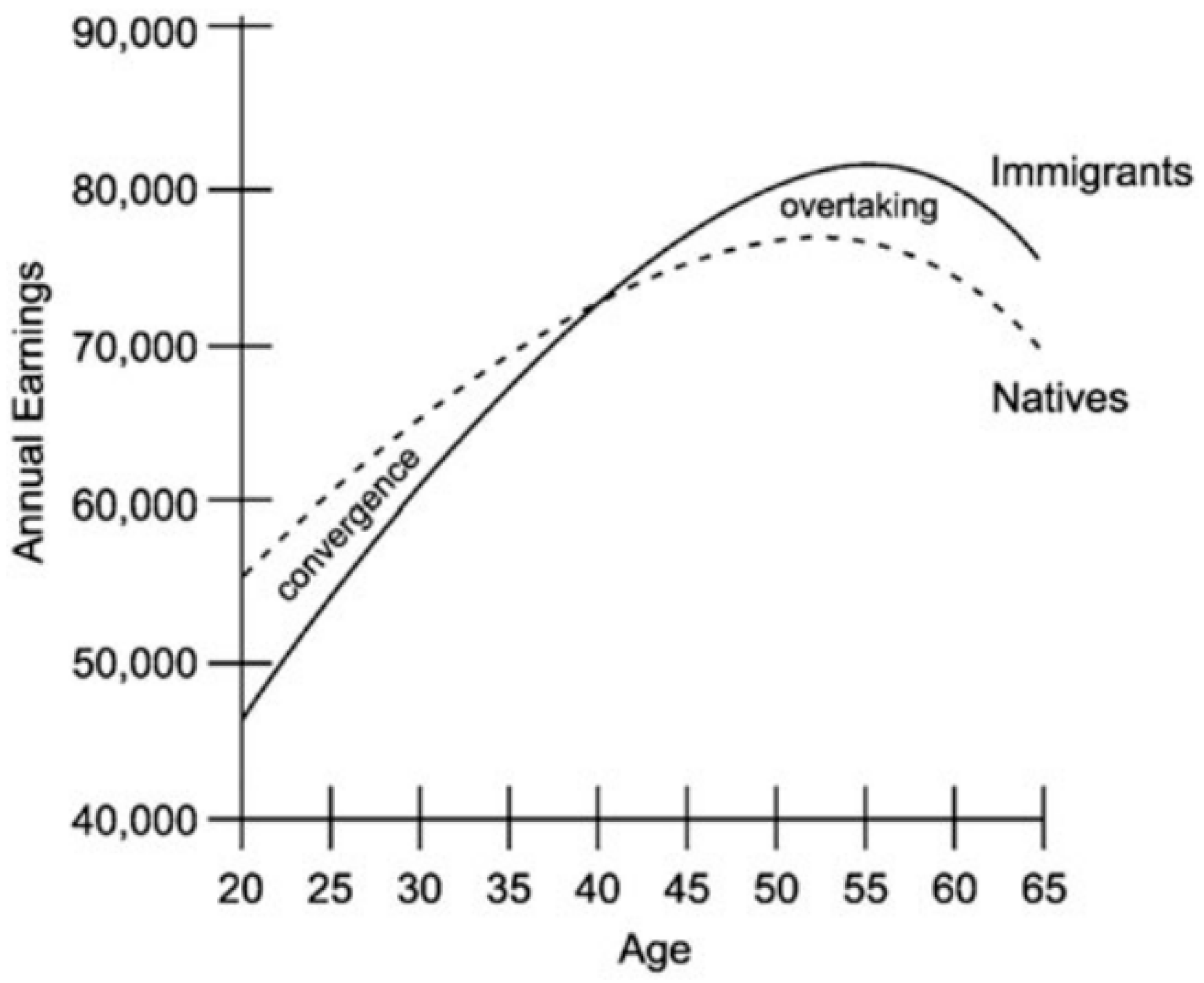

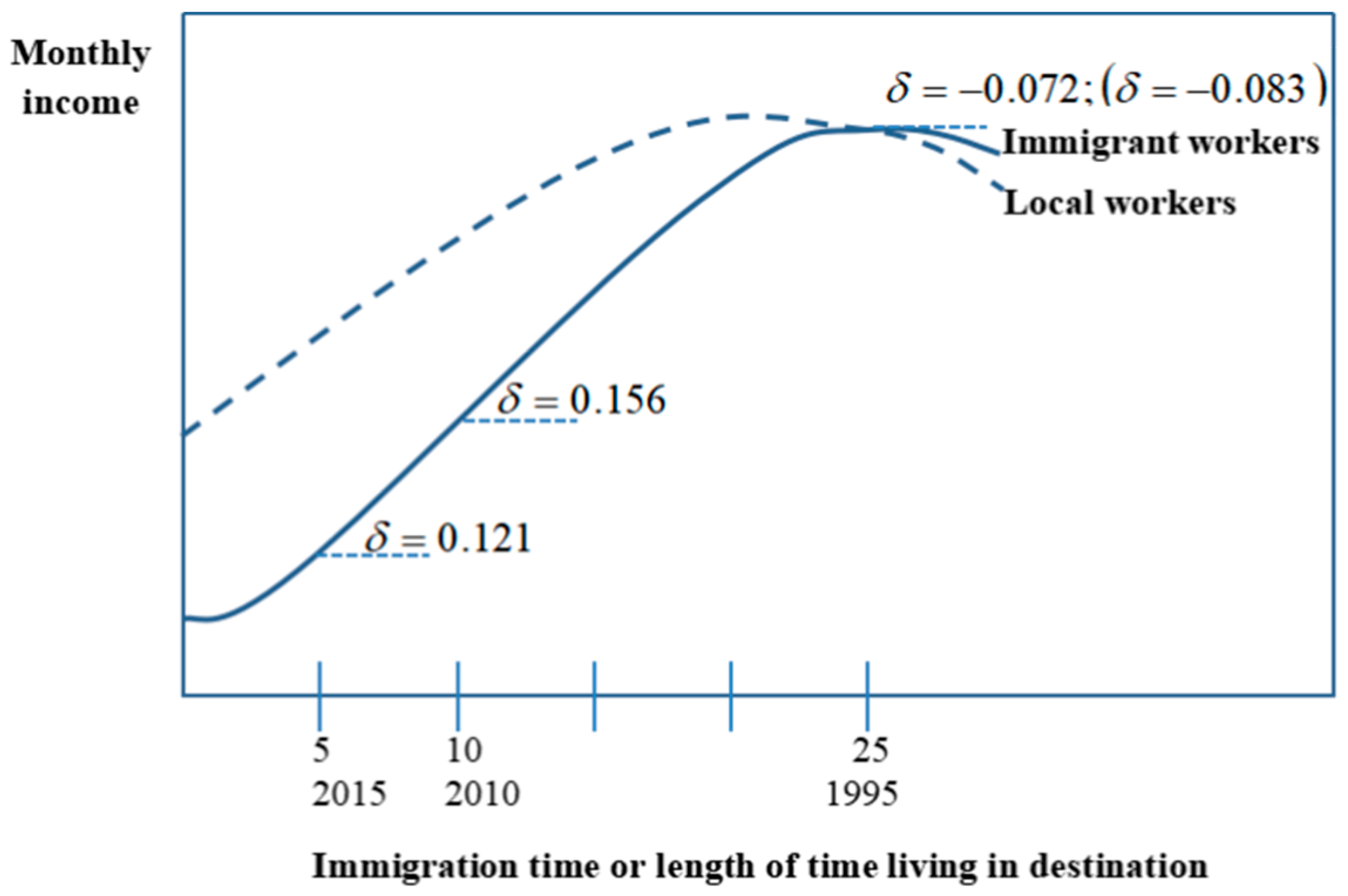

Compared with groups of migrants, the length of time reflects the speed of economic integration of migrants (

Chiswick 1978) or the quality of economic integration (

Borjas. 2014), so “year” means if migrants live in the destination for one more year, their income will increase (

, H

7+). In connection with this, if approaching the concept of

Chiswick (

1978), the period of time reflects the differences among groups of migrants, “year25” implies that the income of the group immigrating in the years 1995 is lower than that of the other groups (

, H

12+); however, this is contrary to the expectation. This estimate is rational with the fact that today’s workforce has more advantages than previous generations. Somewhere migrants who have lived in the destination for many years can be considered local workers. That estimate means the income of local workers is 0.083% lower. From this reversal and year25 is considered as the intersection point, the income of migrants will exceed that of local workers after 25 years of living there (

Figure 4), this result is rational to the argument of

Chiswick (

1978) (

Figure A2). Besides, both “year5”, “year10” and “year25” are significant at the level of 10% (

,

,

, H

8,9,12+), which shows that there are differences in income among these groups, it implies that the income of workers has a return to time (

Figure 4). The immigration time which are the years 1995. 2010. 2015 (year25, year10, year5), was a migration wave to the South such as HCMC and BDP in the years 1995, and correspond to the X generation (born 1965–1979), the microgeneration (1975–1985) or the Y generation (1980–1994). For all those arguments, from

Hajighasemi and Oghazi’s (

2021) suggestion about accelerating the integration to create a positive impact on the economy, it should pay attention to the length of time to reach the 25-year income convergence and shorten it to recover the economy in the pandemic rapidly.

4.2.3. Employment

Variables compose as “wosec”, “seemp” and “insur” showing the difference in income between public and private sector workers, employed and self-employed workers, workers with or without social insurance. The income of workers will be higher if they are working in the private sector or being self-employed, had insurance (

,

,

, H

17,18,20+). Participation in insurance is an agreement in the labor contract, and so if workers have insurance, they also have a labor contract, therefore “contract” is not respective to income and “insur” can be representative to “contract”, insurance is evaluated as the most critical factor (

Brand Vietnam 2018). As mentioned, many workers join in the informal sector or non-standard jobs. They are unable to sign contracts due to circumstances beyond their control, namely part-time jobs, temporary contracts, self-employed work, unclear employment relationships, or online work. According to

Behrendt and Nguyen (

2018), although these kinds of work are flexible, they received a low income and are excluded from social protection. The survey showed a relatively high ratio of migrants working in the private sector and self-employed, 86.3% and 81.1%, respectively. If migrants in the private sector are not forced to possess and constrained by contract terms and are self-employed, they will not return in the short term after the outbreak.

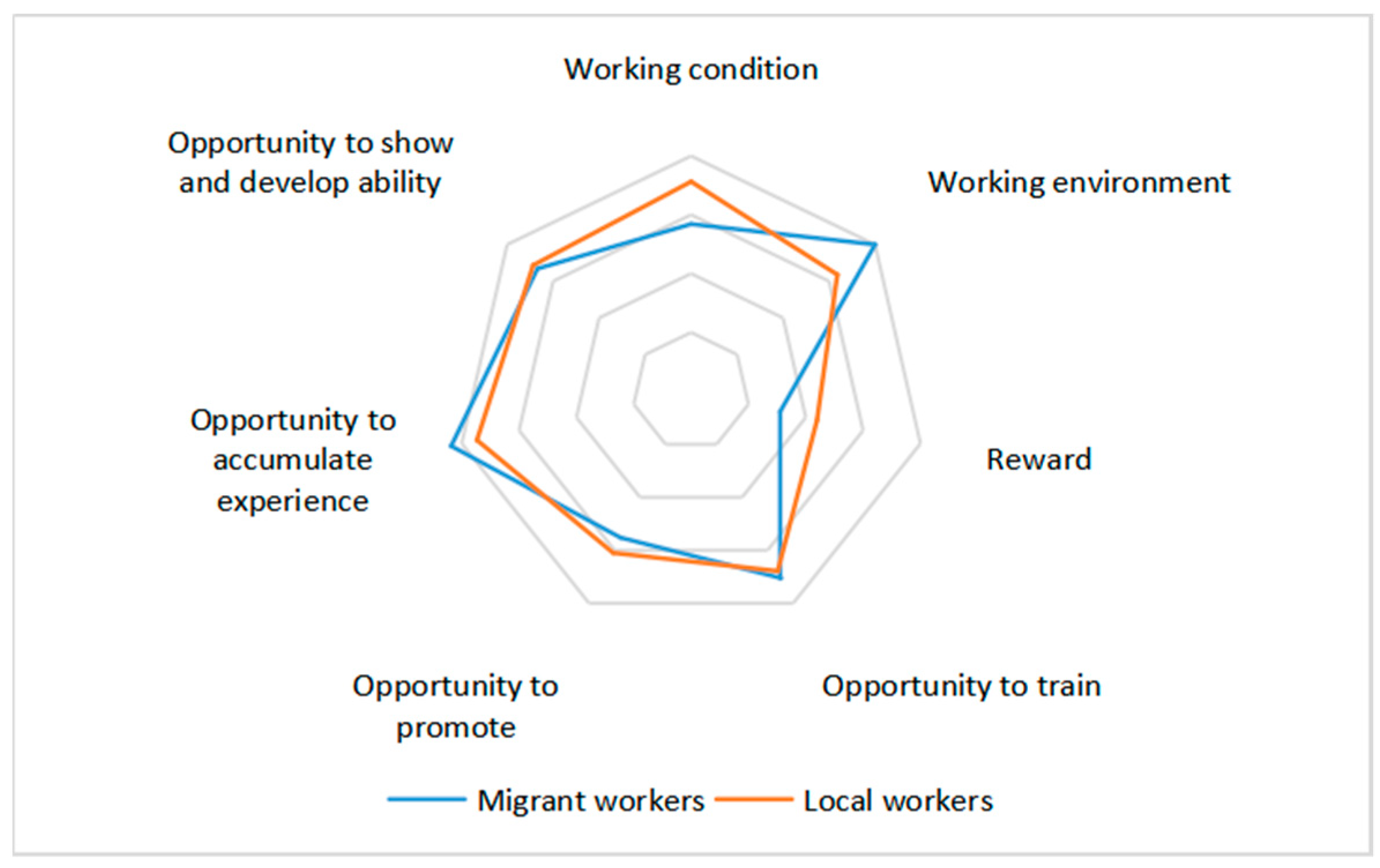

4.2.4. Access to the Urban Utility

Variables “aclama”, “acsocie”, “acsoef” measured the process of workers accessing to the labor market, the local community, and the local community with their intention to stay at a significance of 10%. The estimate shows that the income of workers will be higher if they access better (

,

,

, H

21,23,25+). Access to the labor market is measured through means of job quality and working conditions. The survey showed that immigrants are worse compared to locals in the ways such as access to working conditions, reward, and the opportunity for promotion. In contrast, immigrants are better in terms of the working environment and the opportunity to accumulate experience (

Figure 5). From these results, from

Hajighasemi and Oghazi’s (

2021) suggestion about pushing the integration in the labor market, on the other hand, the businesses should weigh up the components of access to the labor market factor, on the other hand, the workers should contemplate the components of access to the local community factor; however, the government keeps a vital role to connect them.

5. Conclusions and Policy Implications

Attracting labor return to cities affected by COVID-19 is a highly predominant concern of both the government and businesses in the purpose of restoring the broken production chain. From approaching

Hajighasemi and Oghazi (

2021) about promoting labor integration rapidly to make a positive contribution to the economy, the study basically assessed the effectiveness to identify the expectations of residents met basic needs and then estimated a model of income to identify the factors driving the process of integration of workers adapting rapidly in the new normal status.

In the short term, the discretionary measurements are certainly not adequate, and the reliefs are unable to cover or expend for all vulnerable residents. The study suggests the government focus on things the residents expected: (1) simultaneously reduce utility bills, reduce or exempt from electric and water bills, provide food, pressure banks to reduce the interest rate on loans, or extend pay date; (2) remove administrative barriers that prevent businesses from receiving support package on time to pay workers’ salaries.

In the long term, the study has found the most prominent result is identifying the impact factors of income. Firstly, the most crucial results encouraging workers’ income are education, homeownership, work sector, self-employed and social insurance. Secondly, the result also made clear that the significant components which workers expect to access the labor market are working conditions, working environment, reward, the opportunity for promotion, opportunity to accumulate experience. Education or experience and some components related to market labor are similar to many previous studies. However, the other factors have not been verified by the other studies yet. As our best understanding, there are only descriptions concerning these factors. Finally, the study also shows that the length of time to converge income is 25 years.

The study noticed that these findings would be the basis of policy recommendations for helping labor who is currently staying, attracting workers who left to return, and adapting to new normal status. It is also concluded that to incentivize immigrant workers to return to the cities, companies should create for immigrant workers favorable conditions to engage with the working environment, policies with higher bonuses, and opportunities for training and promotions. The workers themselves also need to connect to the social network in order to find a new job quickly or take advantage of this time to study in order to enhance their degree and improve their skills. The government should keep a role in the connection between businesses and workers. According to the model results, the study recommended that government should focus on social policies such as employment, insurance, and housing. Firstly, recognizing migrants’ significant contribution to the city that the equality of compensation will attract and encourage the contribution of migrants, therefore having a decent salary, recruitment, and payment without discriminating between migrants and locals, with or without household registration, and the full implementation of the labor contract. Secondly, focusing on employment policy for migrants is the role of both government and enterprises. In order to create the necessary condition for migrants to access the labor market, by the government migrants are encouraged to change their jobs from being hired to owning through supporting preferential loans for effective projects with lower interest rates and longer periods due to higher living expenses. Enterprises encourage migrants with simple technical barriers, such as accepting lower skills, offering more job opportunities, training and lengthening probationary period, and then reselecting based on the job requirements. Firms should also update information and support migrants to register and access regular incentives from the government. In addition, humans always respond to incentives therefore businesses should help migrants with their living and medical expenses. Many respondents in our survey said that companies should support employees who agree to return to work for at least 1 to 3 months’ salary. Thirdly, prioritizing policies concerning housing conditions. Migrants mainly live in rented houses and in inconvenient locations to work, in one hand the uncontrolled rental housing market leads to pressures on migrants such as the high fee for rent, electricity, water, and cramped accommodation condition; on the other hand, nearly all migrants do not know or have very little information about the housing support program. Therefore in the short term, businesses need to improve the accommodation, meanwhile, the government needs to support landlords by reducing electricity and water bills if agreed to lower the rent when migrants return. In the long term, it is necessary to widely disseminate information to migrants about housing support programs, enhance the control of implementing programs for migrants; mobilize resources in the private sector by tax incentives and loans for efficient housing projects and rental housing projects; to speed up the construction of urban centers in peri-urban districts with full facilities and services, self-employment. Fourthly, focusing on infrastructure and social services in suburban areas. The ideal destination such as HCMC and BDP also have many differences, the former is famous for infrastructure development and suburban housing, the latter stands out for its housing and social security policies, therefore government needs to take advantage of the migration to speed up and improve the efficiency of projects about infrastructure, essential social services, and housing to encourage migrants returning and accepting to live in suburban areas. Finally, migrants need to base social access to long-term migrant workers on initial support regarding employment information, accommodation, education, etc., if long-term migrants are employers, they can promote job creation and support new migrant laborers.

It is clear from these results that short-term policies, such as public support, were not effective and did not satisfy the disadvantaged, and long-term policies should be focused on categories, determined by an estimated model, which improve workers’ income and enhance the process of integration of workers. However, it is necessary to undertake the limitation of this study. First, the sample size for the first objective was limited due to the restriction of the survey conducted in the social distancing, the result did not express completely the ineffectiveness of policies and the difficulties of migrants which pushed them to remigrate. We recommend that increasing observations or using the case study method could be considered. Second, both income and access to social welfare are some types of integration and the latter is significant to the former, but it was insignificant in this study. Respondents were asked if they easily accessed education, health care, housing, transportation, and entertainment so these categories were broad while the sample size was limited. We recommend researchers divide “access to social welfare” into sub-groups of variables and increase the sample size. Finally, income is the final merit of the integration process, integration in income can be also compared in periods, groups or origins of migration, however, due to a lack of general statistical data by time series, we were unable to discover more meaningful results on measuring it. We keep track of this data and get a new survey in the future in order to test the income gap by using the difference-in-difference method.