The Effect of Interest Rate Changes on Consumption: An Age-Structured Approach

Abstract

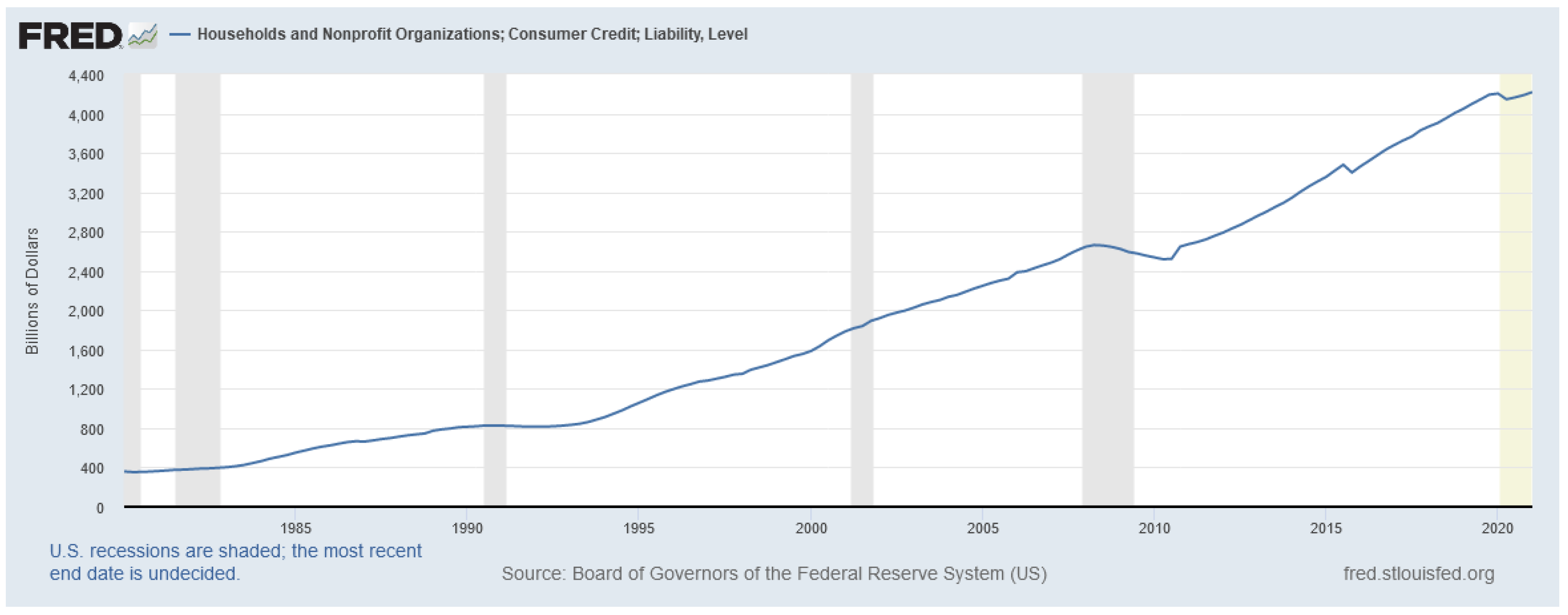

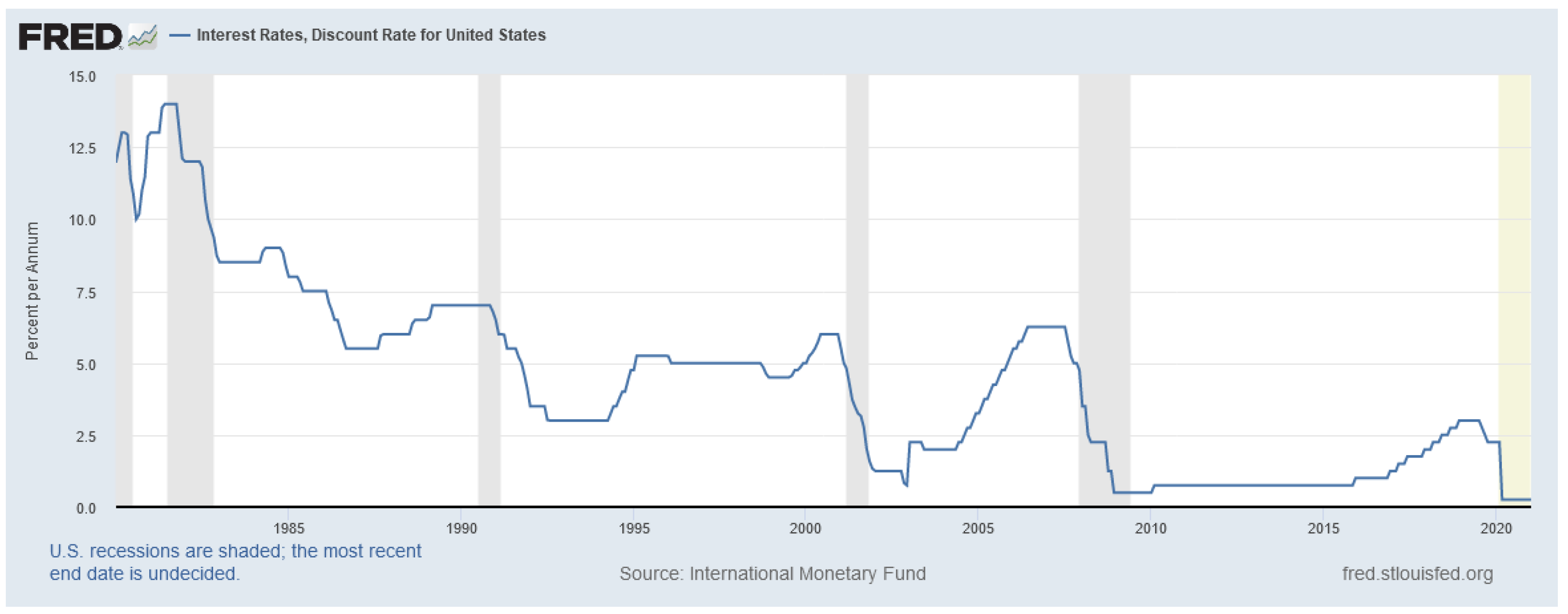

:1. Introduction

- The Permanent Income Hypothesis Friedman (1957): This theory, developed by economist Milton Friedman, suggests that consumer spending is not solely driven by current disposable income, but also by the individual’s expected lifetime income. According to this theory, consumers will adjust their spending to match their expected lifetime income, rather than just their current income.

- The Life Cycle Hypothesis Ando and Modigliani (1963); Modigliani and Brumberg (1954): This theory, developed by economist Franco Modigliani, suggests that consumer spending is influenced by an individual’s life stage and expected future income. According to this theory, younger individuals are more likely to have higher levels of debt and lower levels of savings, while older individuals are more likely to have higher levels of savings and lower levels of debt.

2. The Basic Model

2.1. Model Formulation

2.2. Solution of the Control Problem

2.3. Aggregation for Age Groups

- The average consumption rate

- The average loan value

- The payment for the loan (this short name, which is relevant only for the case , is used for convenience)

2.4. Calibration of the Discount Rate

- , : the maximal loan value

- , : the sum of the maximal loan value and the loan payment

- , : the sum of the average loan value and the loan payment

3. Interest Rate Changes

3.1. Particular Age Groups

- Only with the interest rate if ;

- With both interest rates and if ;

- Only with the interest rate if .

- Case (before the transition)

- The transition case .The interval includes the moment of the interest rate change . The interval is split into two subintervals: with the interest rate and with the interest rate .

- (a)

- .For the interval , the results are the same as for the case :see (29) for and .At the end of this interval, i.e., at time , the household has the loan

- (b)

- At the time , there is a change of the interest rate r and an induced change of the rate of discount . The new values are and . We assume that parameter was fitted as described in Section 2.4. The determination of the parameter is a separate subproblem, which will be discussed in the next subsection.

- (c)

- For the rest, i.e., on the interval , the dynamic is given by Equations (10a)–(10c) with and . The boundary conditions arewhereThe solution is given by the consumption rate,and the loan valueNote that is a function of several parameters and is a constant.

- Case (after the transition)

3.2. Determination of the New Discount Rate

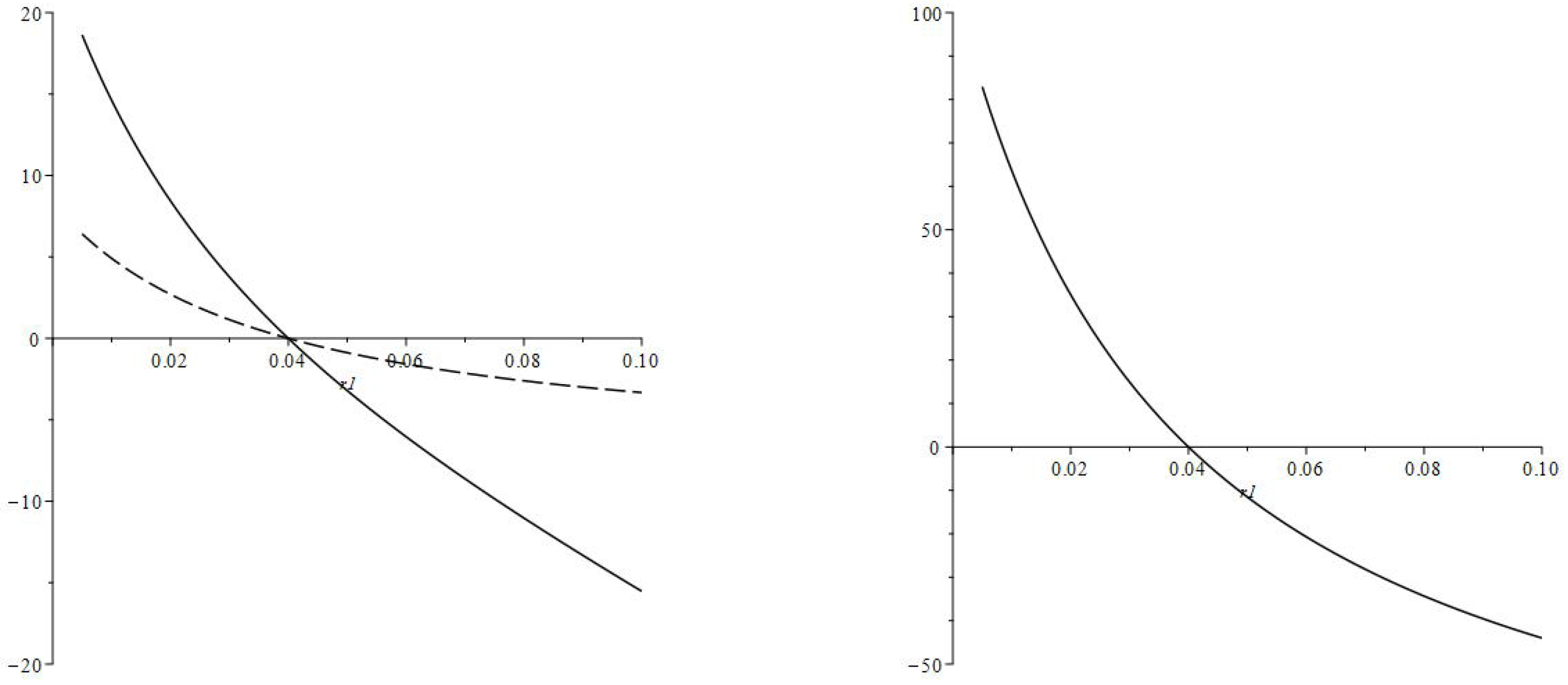

- , .Here, the new and original values are related by assumption that the sum of the maximal loan value and the loan payment is the same for new values and as it was for the original values and , i.e.,

- ,Similarly, we can use the sum of the average loan value and the payment:

- ,For completeness, we can also considerThis approach does not suit small values becauseand

3.3. Averaging for All Age Groups

- Case (before the interest rate change)

- Case (the transition of the consumption patterns)The households are divided into two groups: households with , changing their behavior at , and households with , joining the labor force under the new conditions, i.e., with the interest rate and the discount rate . We getThe integrals with and cannot be found analytically and should be computed numerically. For the integrals with and both analytical and numerical approaches can be used.

- Case (after the transition to the new conditions)

4. Numerical Simulation

4.1. Interest Rate Changes Modeling

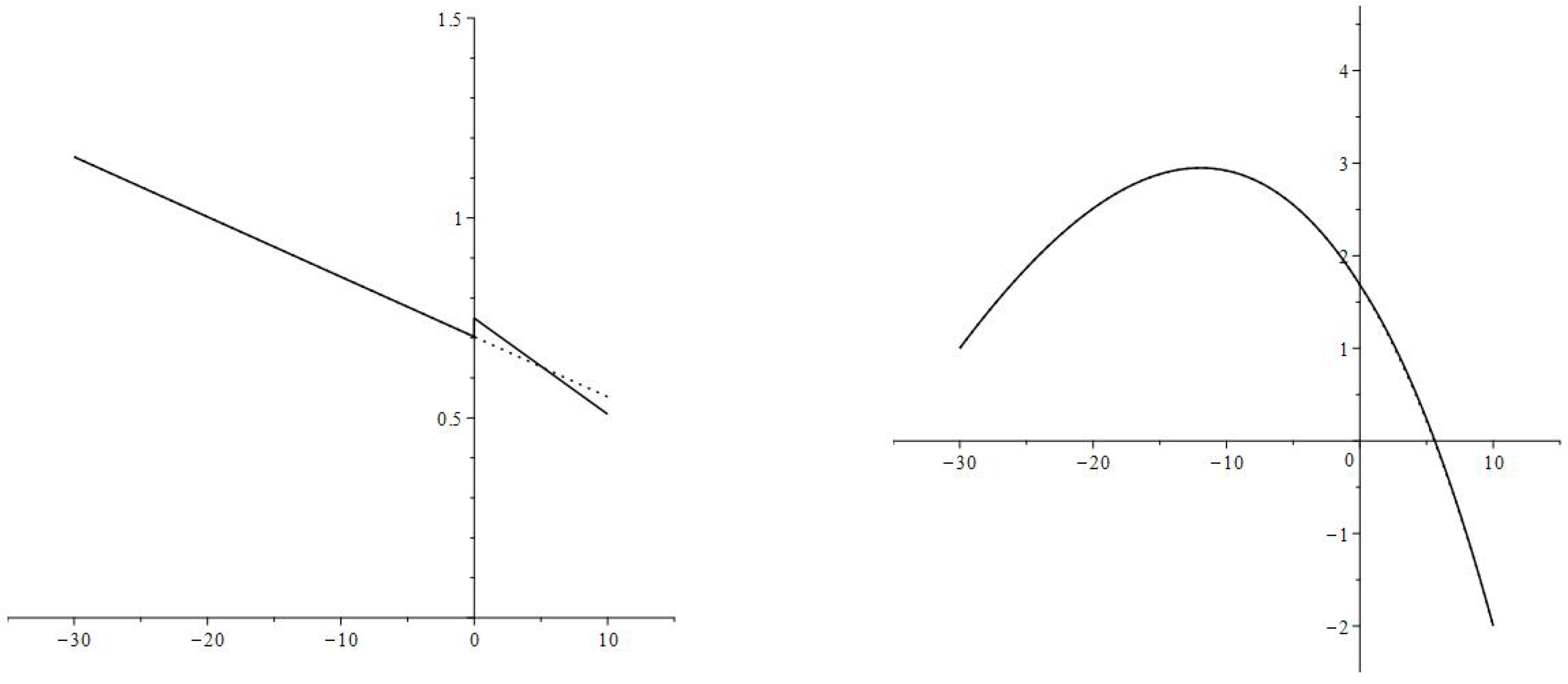

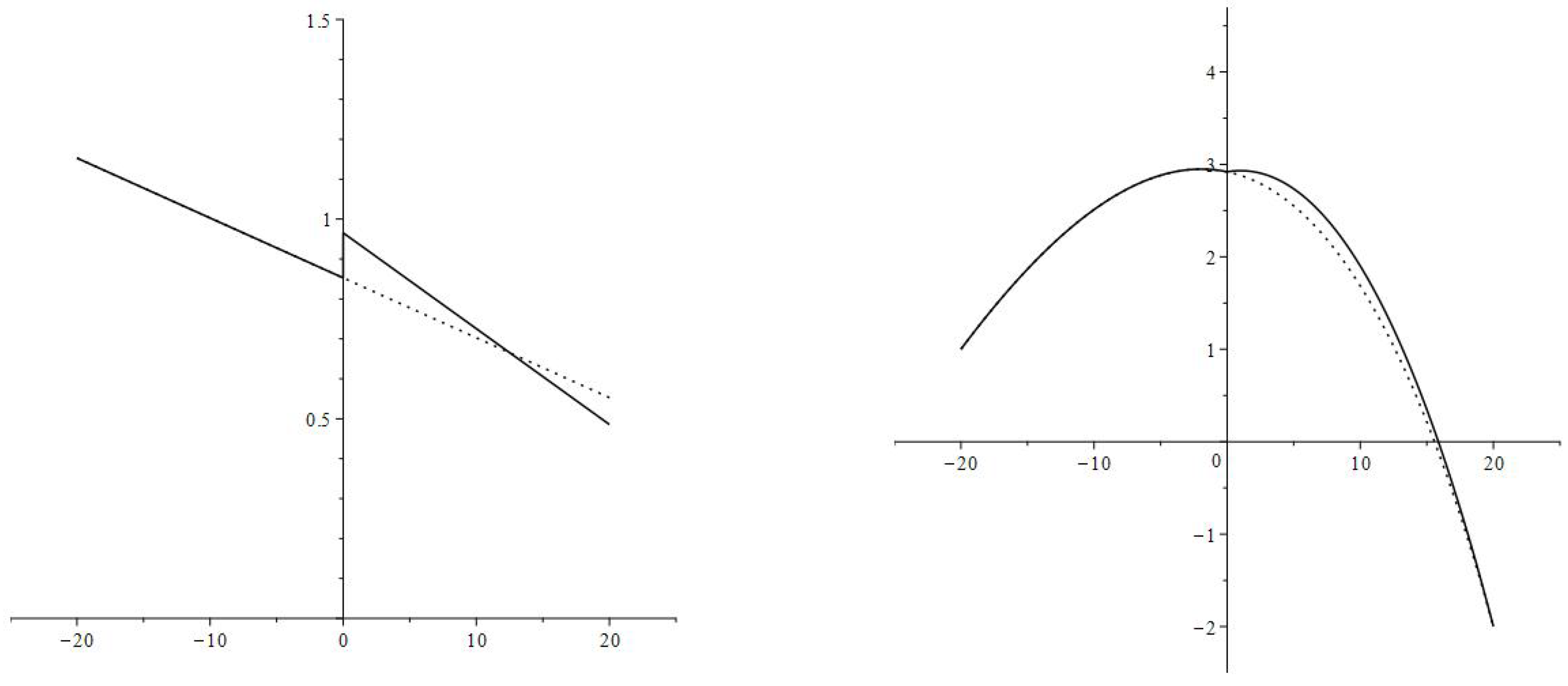

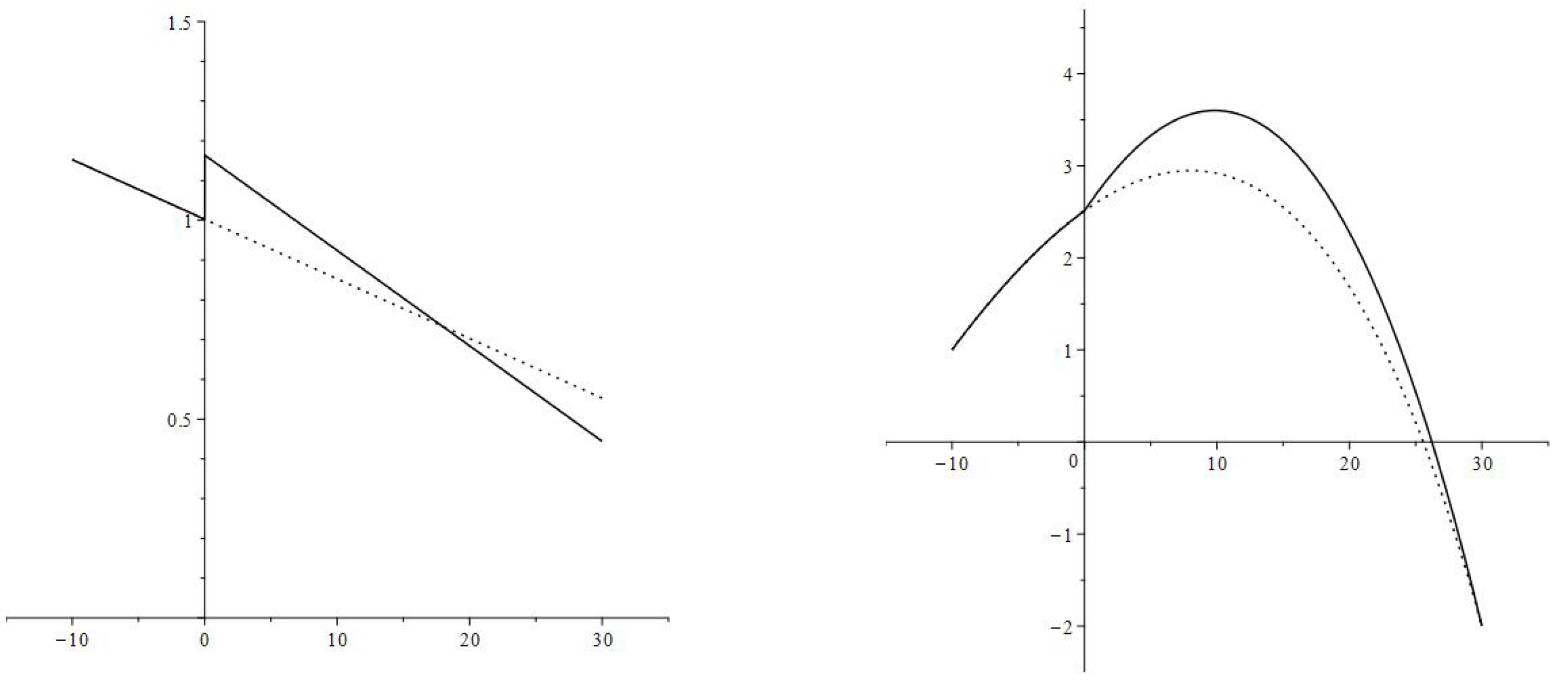

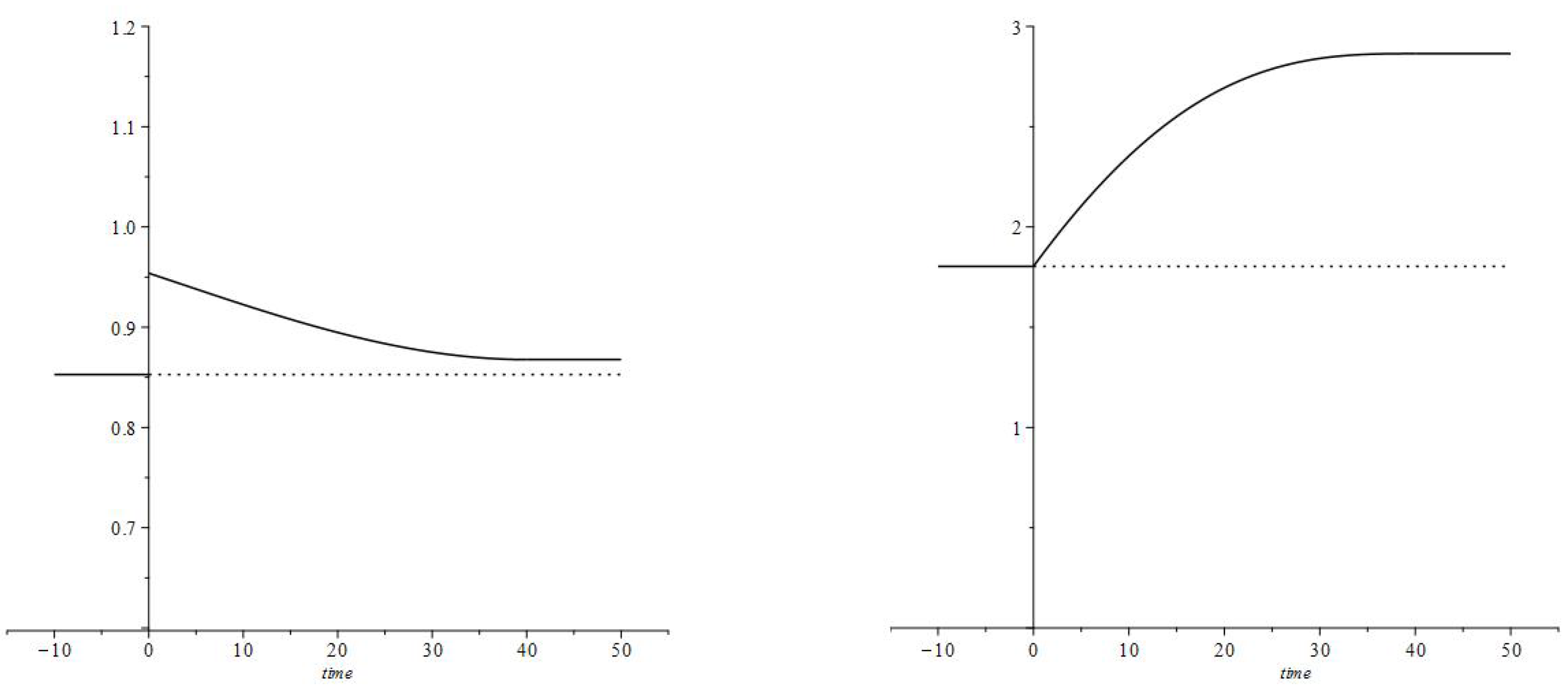

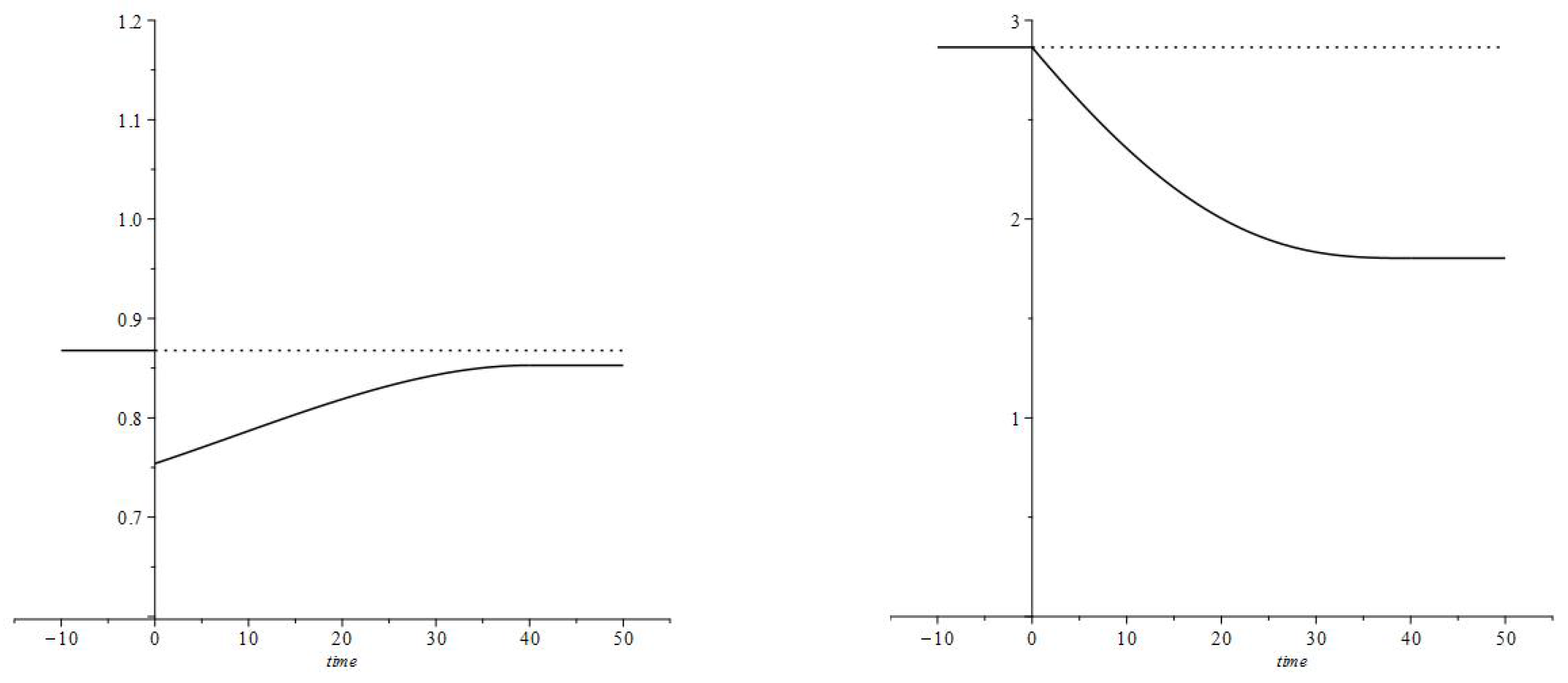

4.1.1. An Interest Rate Decrease

4.1.2. An Interest Rate Increase

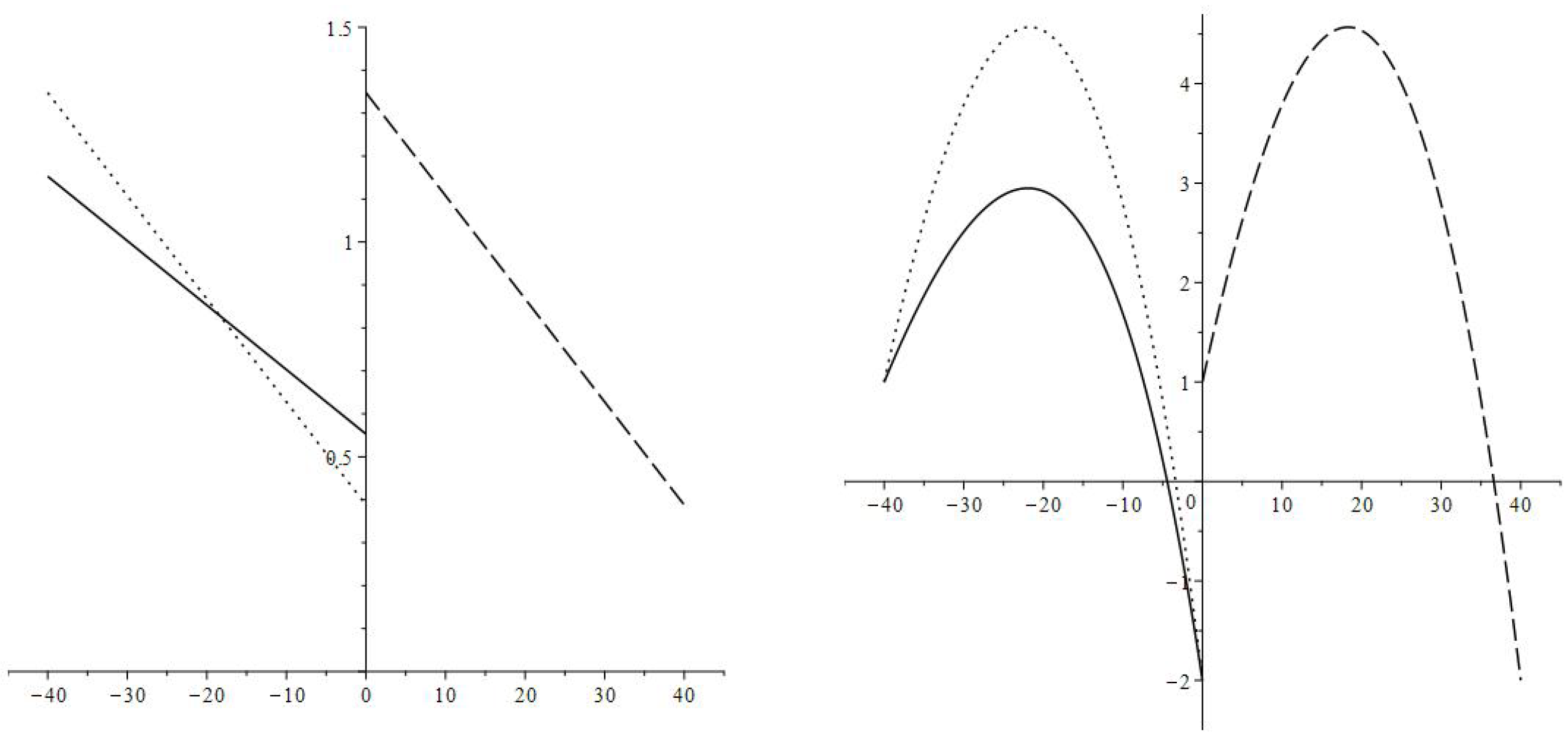

4.2. Different Values of the New Interest Rate

5. Discussion of the Computational Results

- A simple basic model, which describes the consumption pattern of a household representing a specific age group. At this stage, the interest rate is constant;

- Incorporation of interest rate changes into the basics model as a parameter change. This change of the parameters affects the control problem system of Equations (10a)–(10c) The two cases of this system (before and after the interest rate change) are connected by the continuity of the loan value and by a relation determining the new value of the discount rate. The consumption rate is discontinuous at the moment of the interest rate change;

- The results concerning the consumption rates and the loan values for different age groups derive the aggregate values.

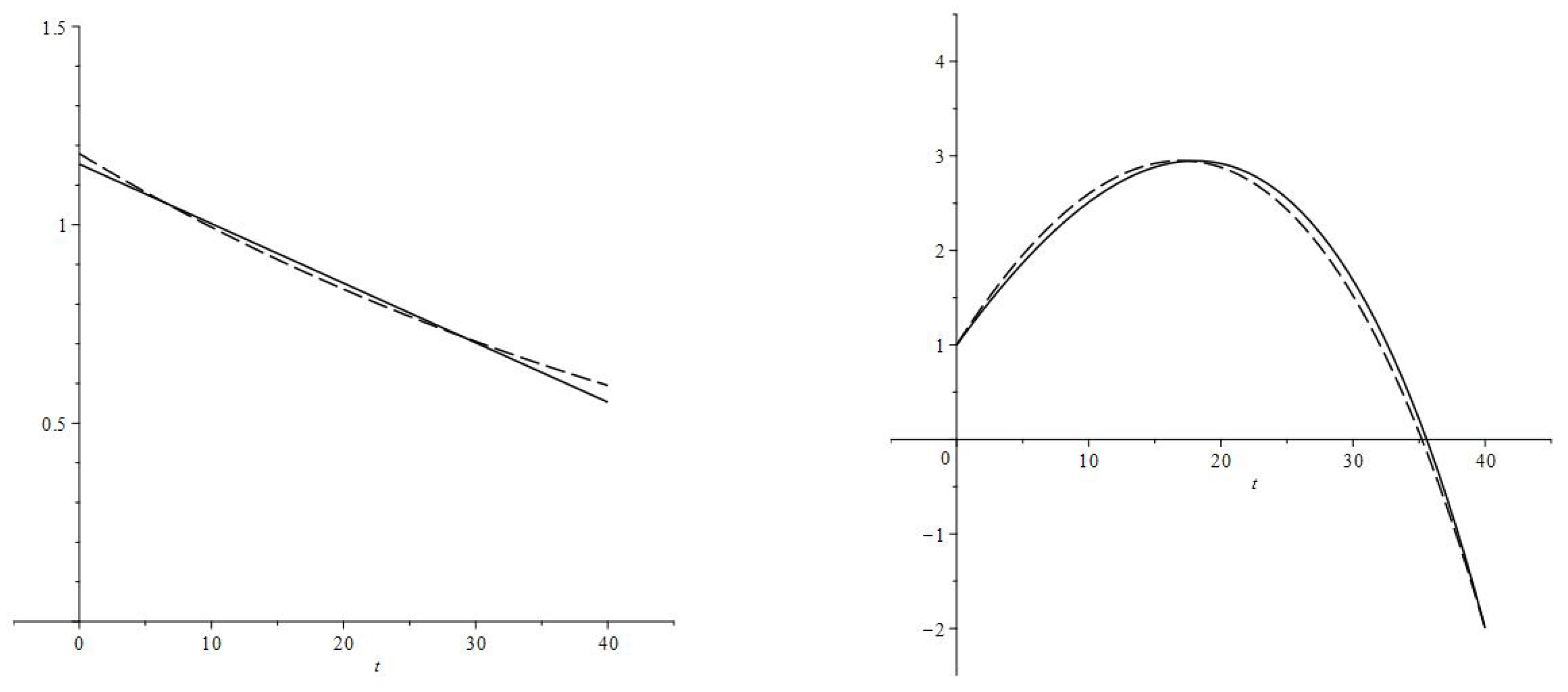

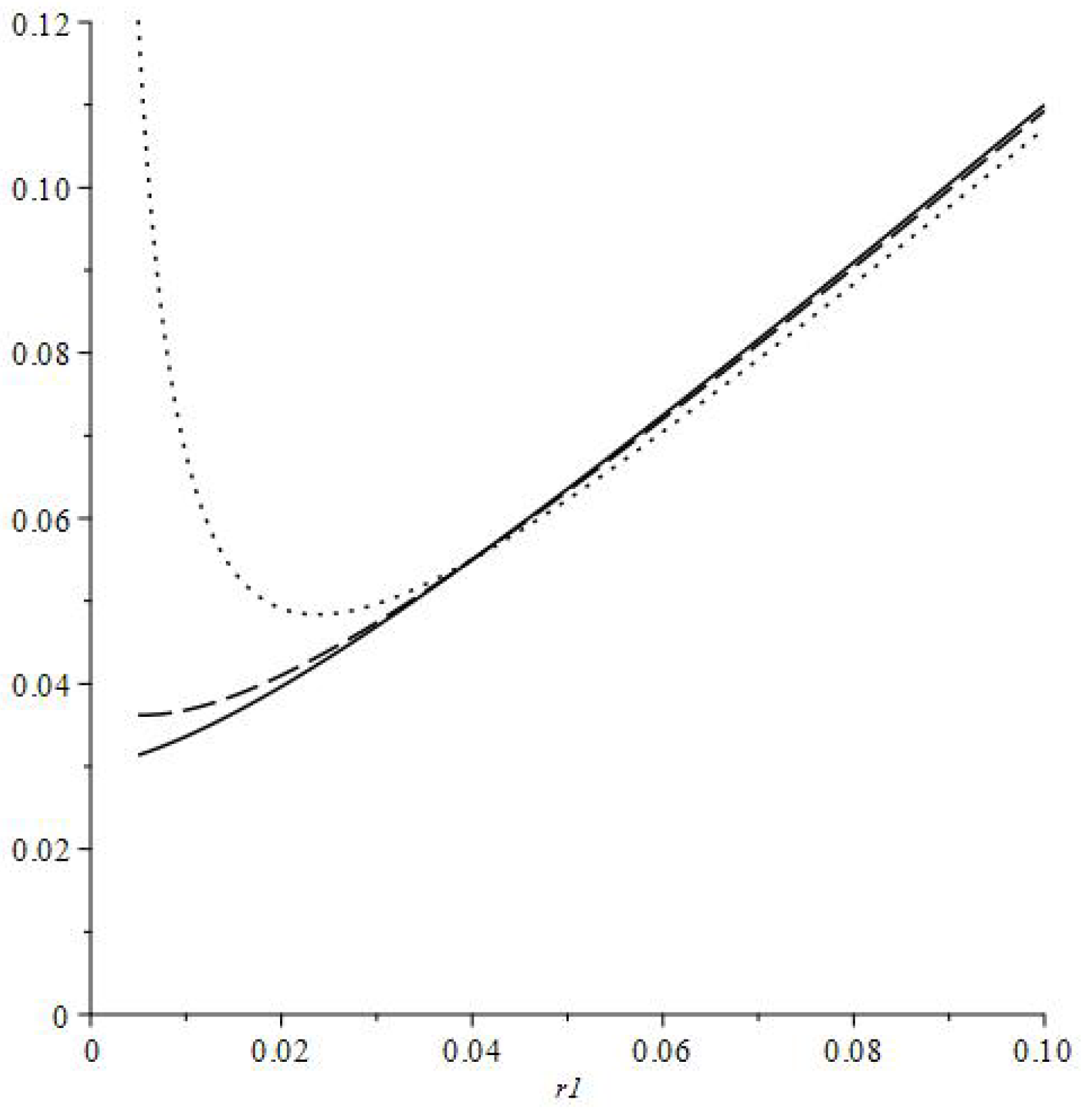

- The increase in consumption rate is most substantial right after the interest rate decrease. The consumption rates for individual age groups and the aggregate consumption rate have jump increases.

- After the immediate jump increase the average consumption rate decreases to the value corresponding to the new interest rate and discount factor (parameters and ). During the transition, the consumption rate is greater then upon the completion of the transition,and is decreasing. In the numerical example, the new consumption rate (the consumption rate upon completion of the transition) is greater than the original consumption rate

- High values of the consumption rate during the transition are achieved by an increase in the debt load:and is increasing.

6. Concluding Remarks

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

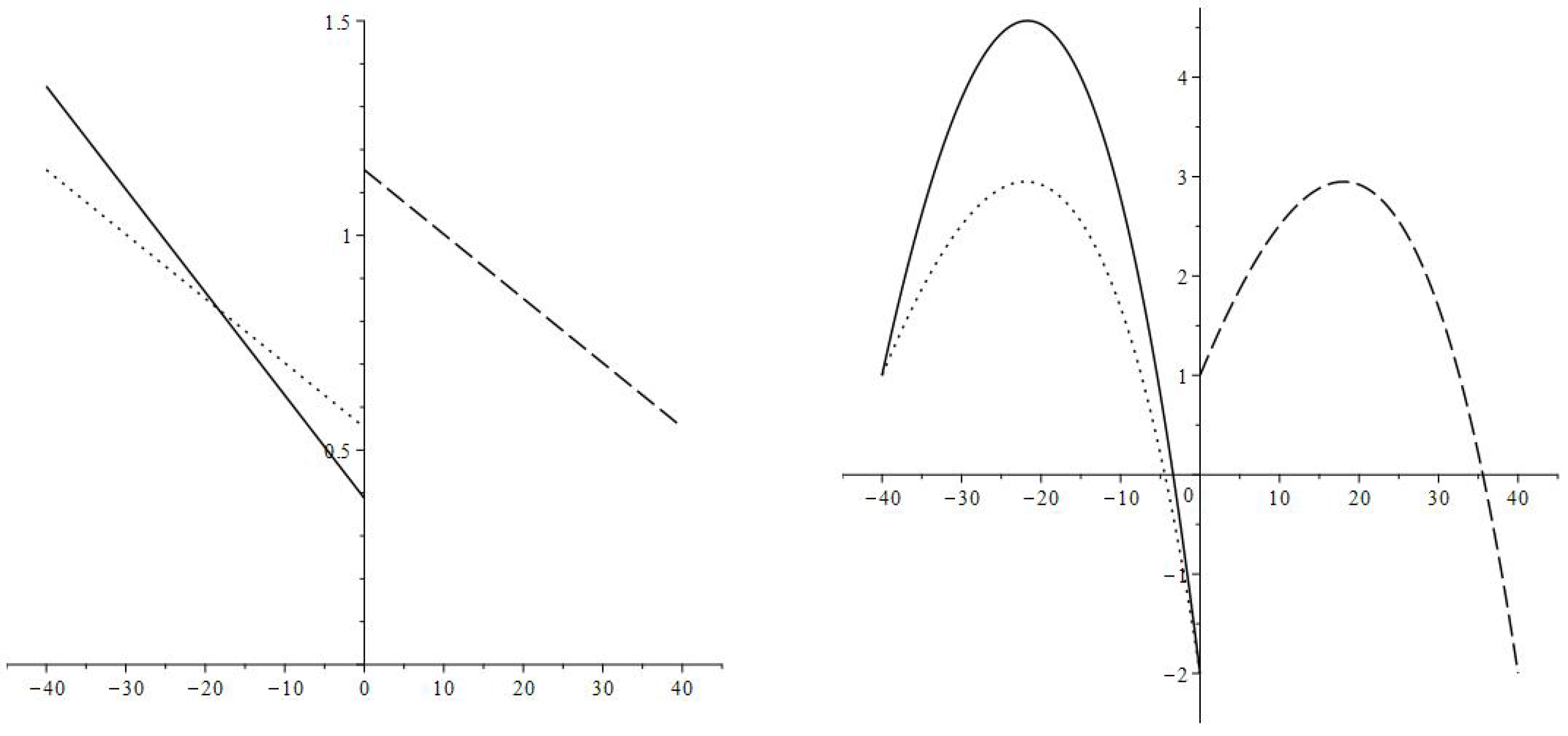

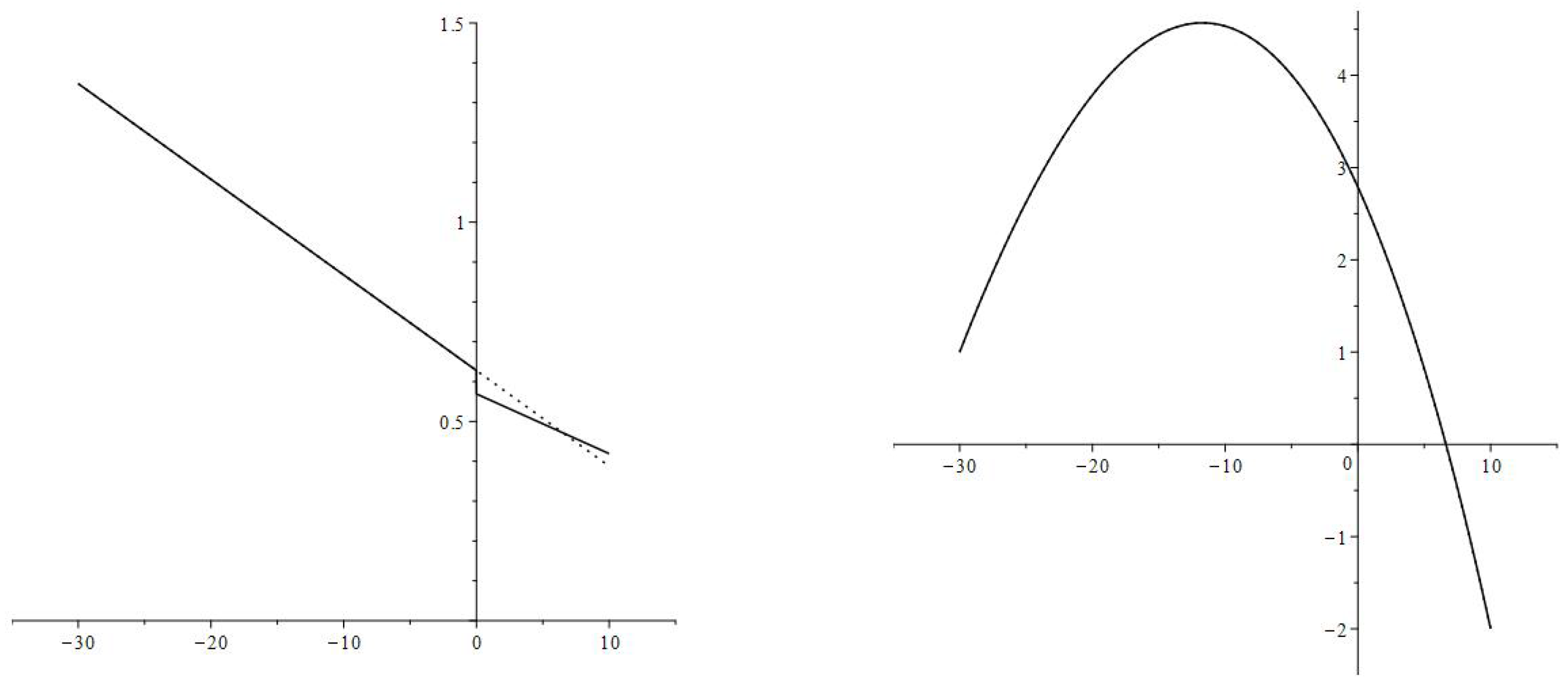

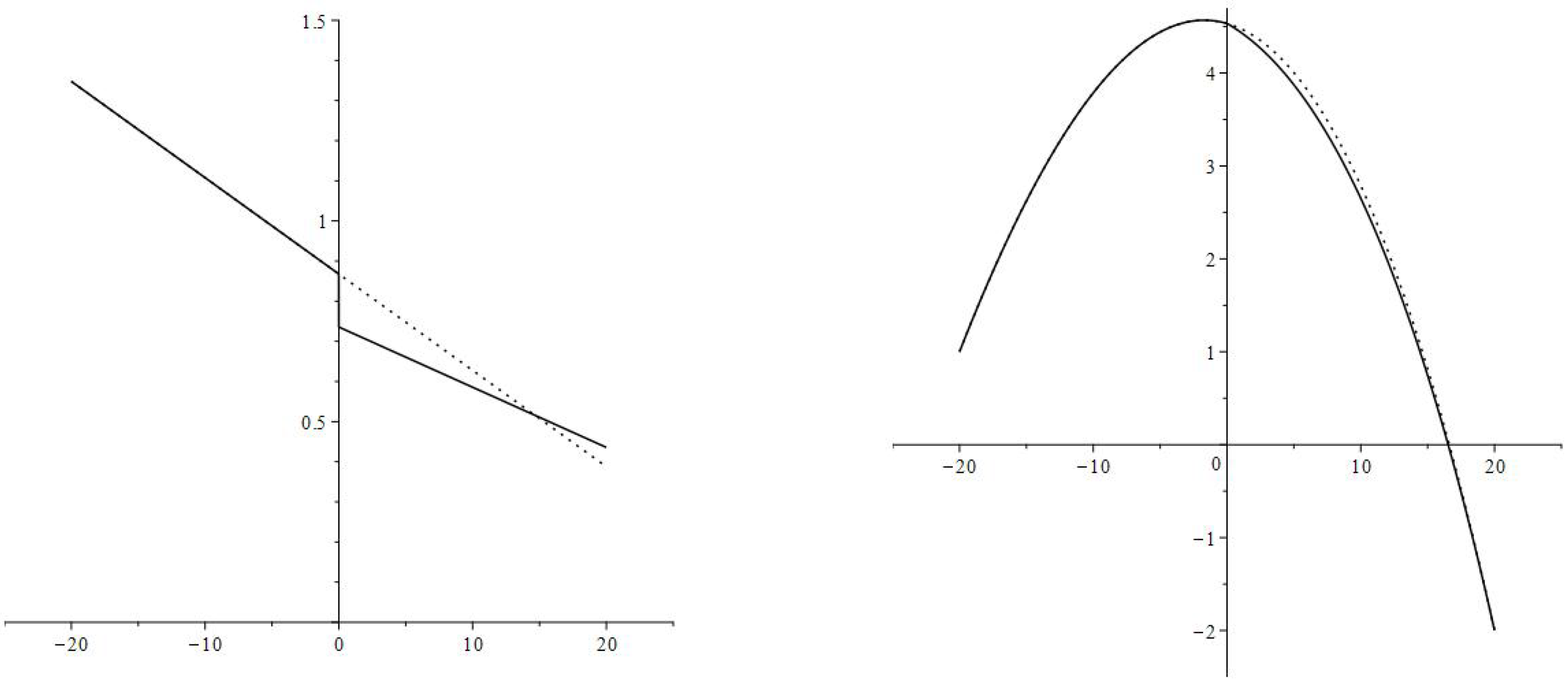

Appendix A. Comparison of Utility Functions

- Exponential utility function :

- Logarithmic utility function :

- Power utility function , :

- Exponential utility function :

- Logarithmic utility function :

- Power utility function , :

Appendix B. The Maximal Loan Value for the Basic Model

References

- Acemoglu, Daron. 2008. Introduction to Modern Economic Growth. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Alogoskoufis, George. 2019. Dynamic Macroeconomics. Cambridge: The MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Alp, Esra, and Ünal Seven. 2019. The dynamics of household final consumption: The role of wealth channel. Central Bank Review 19: 21–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ando, Albert, and Franco Modigliani. 1963. The life cycle hypothesis of saving: Aggregate implications and tests. American Economic Review 53: 55–84. [Google Scholar]

- Attanasio, Orazio P., and Guglielmo Weber. 2010. Consumption and saving: Models of intertemporal allocation and their implications for public policy. Journal of Economic Literature 48: 693–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Barba, Aldo, and Massimo Pivetti. 2009. Rising household debt: Its causes and macroeconomic implications—A long-period analysis. Cambridge Journal of Economics 33: 113–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Blanchard, Olivier. 2019. Public debt and low interest rates. American Economic Review 109: 1197–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Borio, Claudio. 2017. Monetary policy and bank lending in a low interest rate environment: Diminishing effectiveness? Journal of Macroeconomics 54: 1339–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Browning, Martin, and Thomas F. Crossley. 2001. The life-cycle model of consumption and saving. Journal of Economic Perspectives 15: 3–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Caputo, Michael R. 2005. Foundations of Dynamic Economic Analysis: Optimal Control Theory and Applications. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Carlino, Gerald A. 1982. Interest rate effects and intertemporal consumption. Journal of Monetary Economics 9: 223–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, Christopher D. 1994. How does future income affect current consumption? Quarterly Journal of Economics 109: 111–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Christen, Markus, and Ruskin M. Morgan. 2005. Keeping up with the Joneses: Analyzing the effect of income inequality on consumer borrowing. Quantitative Marketing and Economics 3: 145–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cloyne, James, Clodomiro Ferreira, and Paolo Surico. 2020. Monetary policy when households have debt: New evidence on the transmission mechanism. Review of Economic Studies 87: 102–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coskun, Yener, Nicholas Apergis, and Esra Alp Coskun. 2022. Nonlinear responses of consumption to wealth, income, and interest rate shocks. Empirical Economics 63: 1293–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Maggio, Marco, Amir Kermani, Benjamin J. Keys, Tomasz Piskorski, Rodney Ramcharan, Amit Seru, and Vincent Yao. 2017. Interest rate pass-through: Mortgage rates, household consumption, and voluntary deleveraging. American Economic Review 107: 3350–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Friedman, Milton. 1957. A Theory of the Consumption Function. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fortune, Peter, and David L. Ortmeyer. 1985. The roles of relative prices, interest rates, and bequests in the consumption function. Journal of Macroeconomics 7: 381–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerdrup, Karsten R., and Kjersti Næss Torstensen. 2018. The effect of higher interest rates on household disposable income and consumption—A static analysis of the cash-flow channel. Norges Bank, Staff Memo 3. Available online: https://www.norges-bank.no/contentassets/acc6e77108104207bf2d4c8d44c48816/staff_memo_3_2018_eng.pdf?v=04/25/2018122116&ft=.pdf (accessed on 16 August 2021).

- Gourinchas, Pierre-Olivier, and Jonathan A. Parker. 2002. Consumption over the life cycle. Econometrica 70: 47–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Greiner, Alfred, and Bettina Fincke. 2015. Public Debt, Sustainability and Economic Growth. Theory and Empirics. Berlin/Heidelberg: Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Gylfason, Thorvaldur. 1981. Interest Rates, Inflation, and the Aggregate Consumption Function. The Review of Economics and Statistics 63: 233–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hertwich, Edgar G. 2005. Life cycle approaches to sustainable consumption: A critical review. Environmental Science and Technology 39: 4673–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwata, Shigeru, and Shu Wu. 2006. Estimating monetary policy effects when interest rates are close to zero. Journal of Monetary Economics 53: 1395–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, Alison, Gregory W. Fuller, and Aidan Regan. 2021. It takes two to tango: Mortgage markets, labor markets and rising household debt in Europe. Review of International Political Economy 28: 843–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kamien, Morton I., and Nancy Lou Schwartz. 2012. Dynamic Optimization, Second Edition: The Calculus of Variations and Optimal Control in Economics and Management. Dover Books on Mathematics. Chelmsford: Courier Corporation. [Google Scholar]

- Kapeller, Jakob, and Bernhard Schutz. 2014. Debt, boom, bust: A theory of Minsky-Veblen cycles. Journal of Post Keynesian Economics 36: 781–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kaplan, Greg, and Giovanni L. Violante. 2014. A model of the consumption response to fiscal stimulus payments. Econometrica 82: 1199–239. [Google Scholar]

- Keynes, John Maynard. 1936. The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money. London: Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Kureishi, Wataru, Hannah Paule-Paludkiewicz, Hitoshi Tsujiyama, and Midori Wakabayashi. 2021. Time preferences over the life cycle and household saving puzzles. Journal of Monetary Economics 124: 123–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, Siu Fai. 2000. Why Do Some Households Save So Little? A Rational Explanation. Review of Economic Dynamics 3: 771–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mian, Atif, Amir Sufi, and Emil Verner. 2017. Household debt and business cycles worldwide. Quarterly Journal of Economics 132: 1755–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Modigliani, Franco, and Richard Brumberg. 1954. Utility analysis and the consumption function: An interpretation of cross-section data. In Post-Keynesian Economics. Edited by Kenneth K. Kurihara. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, pp. 388–436. [Google Scholar]

- Navarro, Manuel León, and Rafael Flores de Frutos. 2012. Consumption and housing wealth breakdown of the effect of a rise in interest rates. Applied Economics 44: 2091–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navarro, Manuel León, and Rafael Flores de Frutos. 2015. Residential versus financial wealth effects on consumption from a shock in interest rates. Economic Modelling 49: 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novales, Alfonso, Esther Fernández, and Jesús Ruíz. 2014. Economic Growth. Theory and Numerical Solution Methods. Berlin/Heidelberg: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Pontryagin, Lev S., Vladimir G. Boltyanskii, Revaz V. Gamkrelidze, and Evgenii F. Mishechenko. 1962. The Mathematical Theory of Optimal Processes. New York and London: John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Rogoff, Kenneth. 2020. Falling real interest rates, rising debt: A free lunch? Journal of Policy Modeling 42: 778–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sierstad, Atle, and Knut Sydsaeter. 1987. Optimal Control Theory with Economic Applications. Amsterdam: North-Holland. [Google Scholar]

- Tauheed, Linwood, and L. Randall Wray. 2006. System dynamics of interest rate effects on aggregate demand. In Money, Financial Instability and Stabilization Policy. Edited by L. Randall Wray and Mathew Forstater. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Pub, pp. 37–57. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, Mark P. 1999. Real interest rates and macroeconomic activity. Oxford Review of Economic Policy 15: 95–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Tran, Nguyen. 2022. Understanding Household Consumption Behaviour: What do we Learn from a Developing Country? B.E. Journal of Economic Analysis and Policy 22: 801–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, Thomas A. 2011. Optimal Control Theory with Applications in Economics. Cambridge: The MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wolff, Edward N. 2011. Recent trends in household wealth in the U.S.: Rising debt and the middle class squeeze (Book Chapter). In Economics of Wealth in the 21st Century. Edited by Jason M. Gonzalez. New York: Nova Science Publishers, Inc., pp. 1–41. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kozlov, R. The Effect of Interest Rate Changes on Consumption: An Age-Structured Approach. Economies 2023, 11, 23. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies11010023

Kozlov R. The Effect of Interest Rate Changes on Consumption: An Age-Structured Approach. Economies. 2023; 11(1):23. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies11010023

Chicago/Turabian StyleKozlov, Roman. 2023. "The Effect of Interest Rate Changes on Consumption: An Age-Structured Approach" Economies 11, no. 1: 23. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies11010023

APA StyleKozlov, R. (2023). The Effect of Interest Rate Changes on Consumption: An Age-Structured Approach. Economies, 11(1), 23. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies11010023