Quantifying the Macroeconomic Impact of COVID-19-Related School Closures through the Human Capital Channel

Abstract

:1. Introduction

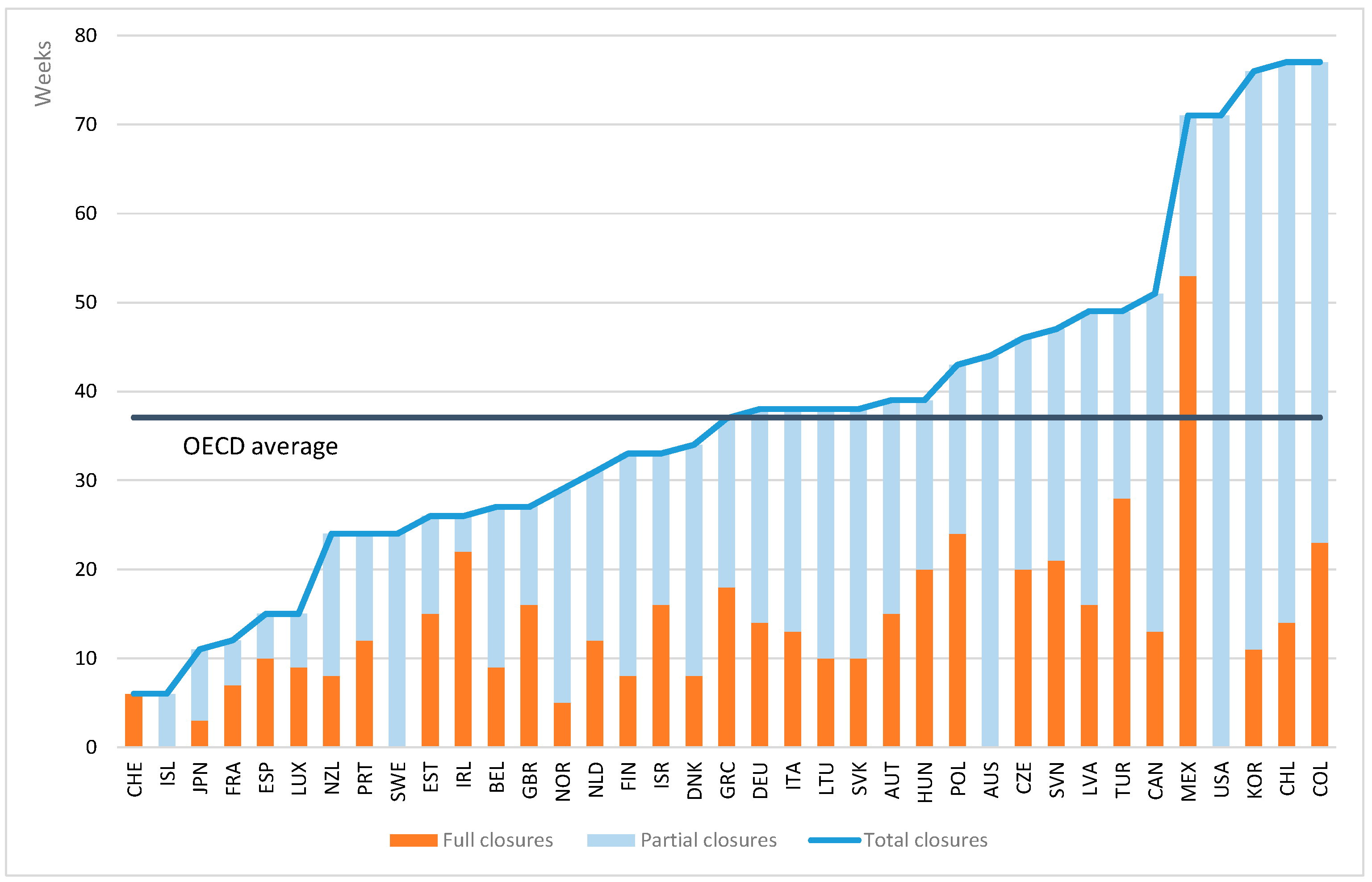

2. Stylised Facts about School Closures in OECD Countries

3. Mitigation Measures Have Been Implemented to Alleviate School Closures

4. The GDP Effect of Pandemic School Closures in the Existing Literature

5. The Impact of School Closures on the Stock of Human Capital

5.1. The Assumptions Underlying the Calculations

- A child attends school between the age of 3 and 18, so that 16 cohorts are potentially impacted in any year and any country;

- Each cohort impacted will enter the labour market one after the other with the first cohort entering in 2021 (those aged 18 in 2020) and the last one in 2036 (those aged 3 in 2020) (Table 2);

- Assuming a working life of 47 years (roughly between the ages 19 and 65 and assuming no increase in the retirement age), one cohort affected by the pandemic, representing 1/47th of the labour force, will enter the labour force each year. Under these stylised assumptions, by 2033 all the affected cohorts will be in the working age population. At that point, they will represent 32% of the working age population, which will be the peak impact on human capital and will be sustained for around 30 years until the retirement of the first cohort that was affected by school closures (Figure 2). At the same time, cohorts in the labour force in 2021 will gradually retire. By 2083, all the affected cohorts will have retired.

5.2. The Empirical Estimations Underlying the Impact Analysis

- PIAAC adult test scores could be used to calculate a cohort weighted stock measure of human capital. Nevertheless, PIAAC has limited country coverage and the PIAAC-based human capital measure has one observation in time, hence making it ill-suited for cross-country time series regression analysis to establish a link with productivity.

- For this reason, PIAAC adult test scores are matched with mean years of schooling and PISA student test scores of the corresponding cohort who took the student tests as 15-year-olds. PIAAC test scores are then regressed on matched PISA test scores and mean years of schooling. This approach has two important advantages. First, the estimated human capital measure covers a wider set of countries and many more years than is available for PIAAC. Second, and very importantly, the relative weights of the quality and quantity components are not imposed or calibrated, unlike in the existing literature, but are estimated directly.

- Feeding the new stock measure of human capital into productivity regressions shows that the elasticity of the stock of human capital with respect to the quality of education is three to four times larger than for the quantity of education (Table 3). The new measure of human capital shows a robust correlation with productivity for OECD countries in cross-country time-series panel regressions, suggesting that a negative shock to human capital may generate important macroeconomic losses. Annex A visualises the COVID-19 impact.

- The effect of the Spring 2020 school closures experienced in many OECD countries, roughly corresponding to one-third of a school year closure. Such a period of school closure translates into a −2.6% decrease in mean years of schooling9 and, using the rule-of-thumb described above, a 0.14 standard deviation fall in PISA scores,10 corresponding to a 1.1% decrease in PISA scores.11

- The effect of a one-year school closure, broadly corresponding to the average total (full and partial) school closures observed across OECD countries since the start of the pandemic and, according to a first assessment, to the learning loss of the most disadvantaged students in the United States (U.S. Department of Education 2022). This scenario translates into a −8.2% decrease in MYS and a −0.37 standard deviation fall in PISA scores, corresponding to a 2.9% decrease in PISA scores.

- The effect of a two-year school closure, which occurred only rarely and broadly corresponding to the total (full and partial) school closure in Colombia, Chile, Korea, and Mexico since the start of the pandemic which translates into a −16.5% decrease in MYS and a 5.6% and a −0.72 standard deviation fall in PISA scores.

5.3. The Negative Effect of School Closures in the Alternative Scenarios

6. The Impact of the Pandemic on Productivity

7. Concluding Remarks

- Extending the teaching time by reducing temporarily school holidays and/or adding hours in a school day.

- Revising the curriculum to focus on key skills. Providing teachers with some training.

- Considering the use of digital technologies to improve diagnosis of learning gaps and facilitate more individualised teaching practices.

- Spreading collaboration and professional ways of working to increase teachers’ effectiveness.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| 1 | |

| 2 | Data on the number of weeks of closures come from UNESCO and are available for full, partial and total closures. It is assumed for the purpose of calculations throughout the paper that a full school year is 38 weeks. |

| 3 | See Kuhfeld et al. (2020) for a summary of the literature on the loss of learning due to summer holidays, weather-related school closures and student absenteeism. |

| 4 | In some low income countries and disadvantaged areas, no offsetting measures were put in place leaving students without education for months (Vincent-Lancrin et al. 2022). See also Mazrekaj and De Witte (2023). |

| 5 | In some countries, children from lower-income households were provided digital material to participate in online learning activities (OECD 2020a). |

| 6 | Using a different perspective, Psacharopoulos et al. (2021) calculate the losses due to school closures in earnings in net present value terms. |

| 7 | The impact for 2050 has been computed by the authors by replicating the simulation that generates a GDP loss of 7.5% in 2100 reported in Hanushek and Woessmann (2020). |

| 8 | Some papers point out that online learning might even improve outcomes by providing the opportunity to review curriculum and provide more efficient teaching methods. Home learning might facilitate a more focussed learning environment for students, who can practice more if needed (Spitzer and Musslick 2021). |

| 9 | The percentage loss in MYS is calculated as the loss in schooling expressed in school years divided by the average MYS for the entire labour force. For example, for a loss of 0.32 school years assuming an average MYS for the entire labour force of 12 years implies a loss in MYS for that cohort of 2.6% (=0.32/12 × 100%). |

| 10 | For 12 weeks, the fall in PISA score is equivalent to 0.14 (12 × 0.012) standard deviation; for 1 year, it is 0.37 (12 × 0.012 + (38 − 12) × 0.009) standard deviation and for 2 years it is 0.72 (12 × 0.012 + (76 − 12) × 0.009) standard deviation. |

| 11 | Percentage loss in PISA = (Estimated impact × PISA standard deviation)/Base PISA score = (−0.14 × 36.1)/462. |

References

- Aghion, Philippe, and Peter Howitt. 1998. Endogenous Growth Theory. Cambridge: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Altinok, Nadir, Noam Angrist, and Harry A. Patrinos. 2018. Global Data Set on Education Quality (1965–2015). World Bank Policy Research Working Paper No. 8314. Washington: World Bank. [Google Scholar]

- Angrist, Noam, Peter Bergman, Caton Brewster, and Moitshepi Matsheng. 2020. Stemming Learning Loss during the Pandemic: A Rapid Randomized Trial of a Low-Tech Intervention in Botswana. CSAE Working Paper Series 2020-13. Oxford: Centre for the Study of African Economies, University of Oxford. [Google Scholar]

- Ardington, Cally, Gabriele Wills, and Janeli Kotze. 2021. COVID-19 learning losses: Early grade reading in South Africa. International Journal of Educational Development 86: 102480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arenas, Andreu, and Lucas Gortazar. 2022. Learning Loss One Year after School Closures: Evidence from the Basque Country. Institut d’Economia de Barcelona Working Paper 2022/03. Barcelona: Universitat de Barcelona. [Google Scholar]

- Asakawa, Shinsuke, and Fumio Ohtake. 2021. Impact of Temporary School Closure Due to COVID-19 on the Academic Achievement of Elementary School Students. Osaka University Discussion Papers in Economics and Business No. 21-14. Osaka: Osaka University. [Google Scholar]

- Azevedo, Joáo Pedro, Amer Hasan, Diana Goldemberg, Syedah Aroob Iqbal, and Koen Geven. 2020. Simulating the Potential Impacts of COVID-19 School Closures on Schooling and Learning Outcomes, A Set of Global Estimates. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper No 9284. Washington: World Bank. [Google Scholar]

- Birkelund, Jesper F., and Kristian. B. Karlson. 2021. No Evidence of a Major Learning Slide 14 Months into the COVID-19 Pandemic in Denmark. SocArXiv. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blainey, Katie, and Timo Hannay. 2021. The Effects of Educational Disruption on Primary School Attainment in Summer 2021: An Analysis of Attainment in Reading, Maths and Grammar, Punctuation and Spelling in Mainstream State Schools in England. Available online: https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=&ved=2ahUKEwj526noi-mCAxVWa94KHYhYDdAQFnoECBIQAQ&url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.risingstars-uk.com%2Fmedia%2FRising-Stars%2FAssessment%2FWhitepapers%2FRSA_Effects_of_disruption_Summer_Aug_2021.pdf&usg=AOvVaw07KcQi1OIjRJKo4DjM3BmX&opi=89978449 (accessed on 27 November 2023).

- Chaban, Tatyana, Roza Rameeva, Ilya Denisov, Julia Kersha, and Roman Zvyagintsev. 2022. Russian Schools during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Impact of the First Two Waves on the Quality of Education. Educational Studies 1: 160–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, Andrew E., Huifu Nong, Hongjia Zhu, and Rong Zhu. 2021. Compensating for academic loss: Online learning and student performance during the COVID-19 pandemic. China Economic Review 68: 101629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Contini, Dalit, Maria L. Di Tommaso, Caterina Muratori, Daniela Piazzalunga, and Lucia Schiavon. 2021. Who Lost the Most? Mathematics Achievement during the COVID-19 Pandemic. The BE Journal of Economic Analysis and Policy 22: 399–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Depping, Denise, Markus Lücken, Franck Musekamp, and Franzisca Thonke. 2021. Kompetenzstände Hamburger Schüler innen vor und während der Corona-Pandemie [Alternative Pupils’ Competence Measurement in Hamburg during the Corona Pandemic], während der Corona-Pandemie. Neue Ergebnisse und Überblick über ein dynamisches Forschungsfeld. Edited by D. Fickermann and B. Edelste. Münster: Waxmann, pp. 51–79. [Google Scholar]

- Dorn, Emma, Bryan Hancock, Jimmy Sarakatsannis, and Ellen Viruleg. 2020. COVID-19 and Student Learning in the United States: The Hurt Could Last a Lifetime. Chicago: McKinsey. [Google Scholar]

- Education Policy Institute. 2021. Understanding Progress in the 2020/21 Academic Year: Interim Findings. London: Department for Education UK, Renaissance Learning. [Google Scholar]

- Égert, Balázs, Christine de la Maisonneuve, and David Turner. 2022. A New Macroeconomic Measure of Human Capital Exploiting PISA and PIAAC: Linking Education Policies to Productivity. OECD Economics Department Working Papers No. 1709. Paris: OECD Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Elango, Sneha, Jorge L. Garcia, James J. Heckman, and Andrés Hojman. 2015. Early Childhood Education. NBER Working Paper No. 21766. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Engzell, Per, Arun Frey, and Mark D. Verhagen. 2021. Learning loss due to school closures during the COVID-19 pandemic. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 118: e2022376118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gambi, Letizia, and Kristof de Witte. 2021. The Resiliency of School Outcomes after the COVID-19 Pandemic. Standardised Test Scores and Inequality One Year after Long Term School Closures. Discussion Paper Series DPS21.12. Leuven: Leuven Economics of Education Research. [Google Scholar]

- Gore, Jennifer, Leanne Fray, Andrew Miller, Jess Harris, and Wendy Taggart. 2021. The impact of COVID-19 on student learning in New South Wales primary schools: An empirical study. The Australian Educational Researcher 48: 605–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, Francis. 2020. Schoolwork in Lockdown: New Evidence on the Epidemic of Educational Poverty. LLAKES Research Paper 67. London: UCL Institute of Education. [Google Scholar]

- Haelermans, Carla, Madelon Jacobs, Lynn van Vugt, Bas Aarts, Henry Abbink, Chayenne Smeets, Rolf van der Velden, and Sanne van Wetten. 2021. A Full Year COVID-19 Crisis with Interrupted Learning and Two School Closures: The Effects on Learning Growth and Inequality in Primary Education. ROA Research Memoranda No. 009. Maastricht: ROA. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanushek, Erik A., and Ludger Woessmann. 2020. The Economic Impacts of Learning Losses. OECD Education Working Papers, No. 225. Paris: OECD Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hevia, Felipe J., Samana Vergara-Lope Tristan, Anabel Velásquez-Durán, and David Calderón Martín del Campo. 2021. Estimation of the fundamental learning loss and learning poverty related to COVID-19 pandemic in Mexico. International Journal of Educational Development 88: 102515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakubowski, Maciej, Tomasz Gajderowicz, and Sylwia Wrona. 2022. Achievement of Secondary School Students after Pandemic Lockdown and Structural Reforms of Education System. Evidence Institute Policy Note 1/2022. Warszawa: Evidence Institute Policy. [Google Scholar]

- Kogan, Vladimir, and Stéphane Lavertu. 2021. The COVID-19 Pandemic and Student Achievement on Ohio’s Third-Grade English Language Arts Assessment. Columbus: The Ohio State University, John Glenn College of Public Affairs. [Google Scholar]

- Korbel, Václav, and Daniel Prokop. 2021. Czech Students Lost 3 Months of Learning after a Year of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Prague: PAQ Research. [Google Scholar]

- Kuhfeld, Megan, James Soland, and Karyn Lewis. 2022. Test Score Patterns across Three COVID-19-Impacted School Years. EdWorkingPapers No. 22-521. Providence: Annenberg, Brown University. [Google Scholar]

- Kuhfeld, Megan, James Soland, Beth Tarasawa, Angela Johnson, Erik Ruzek, and Jing Liu. 2020. Projecting the Potential Impacts of COVID-19 School Closures on Academic Achievement. EdWorkingPapers No. 20-226. Providence: Annenberg, Brown University. [Google Scholar]

- Lichand, G., C. A. Doria, O. L. Neto, and J. Cossi. 2021. The Impacts of Remote Learning in Secondary Education: Evidence from Brazil during the Pandemic. Technical note No IDB-TN-02214. Washington: Inter-American Development Bank. [Google Scholar]

- Lucas, Robert E., Jr. 1988. On the mechanics of economic development. Journal of Monetary Economics 22: 3–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ludewig, U., R. Kleinkorres, R. Schaufelberger, T. Schlitter, R. Lorenz, C. Koenig, A. Frey, and N. McElvany. 2022. COVID-19 Pandemic and Student Reading Achievement—Findings from a School Panel Study. Frontiers in Psychology 13: 876485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maldonado, Joana E., and Kristof De Witte. 2020. The Effect of School Closures on Standardised Student Test Outcomes. KU Leuven, Faculty of Economics and Business. Available online: https://lirias.kuleuven.be/retrieve/588087 (accessed on 27 November 2023).

- Manioudis, Manolis, and Giorgos Meramveliotakis. 2022. Broad strokes towards a grand theory in the analysis of sustainable development: A return to the classical political economy. New Political Economy 27: 866–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazrekaj, Deni, and Kristof De Witte. 2023. The Impact of School Closures on Learning and Mental Health of Children: Lessons From the COVID-19 Pandemic. Perspectives on Psychological Science. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meeter, Martijn. 2021. Primary school mathematics during the COVID-19 pandemic: No evidence of learning gaps in adaptive practicing results. Trends in Neuroscience and Education 25: 100163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molato-Gayares, Rhea, Albert Park, David A. Raitzer, Daniel Suryadarma, Milan Thomas, and Paul Vandenberg. 2022. How to Recover Learning Losses from COVID-19 School Closures in Asia and the Pacific. ADB Briefs No 217. Manila: Asian Development Bank. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. 2017. PISA for Development and the Sustainalble Development Goals. PISA for Development Brief No. 17. Paris: OECD. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. 2020a. Strengthening Online Learning When Schools Are Closed: The Role of Families and Teachers in Supporting Students during the COVID-19 Crisis. Paris: OECD publishing. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. 2020b. Lessons for Education from COVID-19: A Policy Maker’s Handbook for More Resilient Systems. Paris: OECD Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD-Education International. 2021. Principles for an Effective and Equitable Educational Recovery. Paris: OECD Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Patrinos, Harry A., Emiliana Vegas, and Rohan Carter-Rau. 2022. An Analysis of COVID-19 Student Learning Loss. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper No 10033. Washington: World Bank Group. [Google Scholar]

- Pier, Libby, Michael Christian, Hayley Tymeson, and Robert H. Meyer. 2021. COVID-19 Impacts on Student Learning, Evidence from Interim Assessments in California. [Report]. Policy Analysis for California Education. Available online: https://edpolicyinca.org/publications/COVID-19-impacts-student-learning (accessed on 27 November 2023).

- Psacharopoulos, George, Victoria Collis, Harry A. Patrinos, and Emiliana Vegas. 2021. The COVID-19 Cost of School Closures in Earnings and Income across the World. Comparative Education Review 65: 271–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romer, Paul M. 1990. Endogenous technological change. Journal of Political Economy 99, Pt 2: S71–S102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, Susan, Karim Badr, Lydia Fletcher, Tara Paxman, Pippa Lord, Simon Rutt, Ben Styles, and Liz Twist. 2021. Impact of School Closures and Subsequent Support Strategies on Attainment and Socio-Emotional Wellbeing. London: Education Endowment Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Schult, Johannes, Nicole Mahler, Benjamin Fauth, and Marlit A. Lindner. 2021. Did students learn less during the COVID-19 pandemic? Reading and mathematics competencies before and after the first pandemic wave. PsyArXiv. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuurman, Tessa M., Lotte F. Henrichs, Noémi K. Schuurman, Simone Polderdijk, and Lisette Hornstra. 2021. Learning Loss in Vulnerable Student Populations After the First COVID-19 School Closure in the Netherlands. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research 67: 309–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skar, Gustaf B. U., Steve Graham, and Alan Huebner. 2021. Learning Loss During the COVID-19 Pandemic and the Impact of Emergency Remote Instruction on First Grade Students’ Writing: A Natural Experiment. Journal of Educational Psychology 114: 1553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spitzer, Markus W. H., and Sebastian Musslick. 2021. Academic performance of K-12 students in an online-learning environment for mathematics increased during the shutdown of schools in wake of the COVID-19 pandemic. PLoS ONE 16: e0255629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Storey, Nathan, and Qiyang Zhang. 2021. A Meta-analysis of COVID Learning Loss. EdArXiv. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomasik, Martin J., Laura A. Helbling, and Urs Moser. 2020. Educational gains of in-person vs. distance learning in primary and secondary schools: A natural experiment during the COVID-19 pandemic school closures in Switzerland. International Journal of Psychology 56: 566–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomislav, Klarin. 2018. The concept of sustainable development: From its beginning to the contemporary issues. Zagreb International Review of Economics & Business 21: 67–94. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Education. 2022. Institute of Education Sciences, National Center for Education Statistics. National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP), 2020 and 2022 Long-Term Trend (LTT) Reading and Mathematics Assessments; Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Education.

- UK Department of Education. 2021. Understanding Progress in the 2020/21 Academic Year, Complete Findings from the Spring Term London. Manchester: UK Department of Education. [Google Scholar]

- van der Velde, Maarten, Florian Sense, Rinske Spijkers, Martijn Meeter, and Hedderik van Rijn. 2021. Lockdown Learning: Changes in Online Study Activity and Performance of Dutch Secondary School Students during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Frontiers in Education 6: 712987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vegas, Emiliana. 2022. COVID-19′s Impact on Learning Losses and Learning Inequality in Colombia. Washington: Center for Universal Education at Brookings. [Google Scholar]

- Viana Costa, Daniela, Erbabian Maddison, and Youran Wu. 2021. COVID-19 Learning Loss: Long-Run Macroeconomic Effects Update. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania. [Google Scholar]

- Vincent-Lancrin, Stéphan, Cristóbal Cobo Romaní, and Fernando Reimers, eds. 2022. How Learning Continued during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Global Lessons from Initiatives to Support Learners and Teachers. Paris: OECD Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woessmann, Ludger, Vera Freundl, Elisabeth Grewenig, Philipp Lergetporer, Katharina Werner, and Larissa Zierow. 2020. Education in the Coronavirus Crisis: How Did Schoolchildren Spend Their Time When Schools Were Closed, and What Educational Measures Do the Germans Advocate? Ifo Schnelldienst 73: 25–39. [Google Scholar]

| Authors | Countries | Effect on GDP level |

|---|---|---|

| Dorn et al. (2020) | United States | −1.1 to −1.8% (in 2040) |

| Hanushek and Woessmann (2020) | OECD countries and some emerging economies | −4.7% (in 2050) |

| Viana Costa et al. (2021) | United States | −1.8% (in 2051) |

| Oldest Cohort Affected | Youngest Cohort Affected | |

|---|---|---|

| Age in 2020 | 18 | 3 |

| Year of entry in the labour market | 2021 | 2036 |

| Year of retirement | 2068 | 2083 |

| Coefficient of Variation | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent variable: log(adult test scores) | 1.4 | ||

| α | Constant | 3.732 *** | |

| (0.25) | |||

| β | log (Student test score), all cohorts | 0.278 *** | 1.5 |

| (baseline effect) | (0.04) | ||

| δ | log (Student test score), cohorts 50–59 | −0.009 *** | 1.4 |

| (additional effect) | (0.00) | ||

| θ | log (Student test score), cohorts 60–65 | −0.015 *** | 1.1 |

| (additional effect) | (0.00) | ||

| λ | log (Mean years of schooling (MYS)) | 0.083 *** | 5.0 |

| (0.01) | |||

| Adjusted R-squared | 0.934 | ||

| Number of observations | 220 | ||

| Number of countries | 34 | ||

| Country fixed effects | YES |

| Paper | Country | Duration in Weeks | Effect on PISA in Standard Deviation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gore et al. (2021) | Australia | 8 | 0.00 |

| Maldonado and Witte (2020) | Belgium (Flanders) | 9 | −0.24 |

| Gambi and de Witte (2021) | Belgium (Flanders) | 10 | −0.18 |

| Angrist et al. (2020) | Botswana | 12 | −0.29 |

| Lichand et al. (2021) | Brazil | 26 | −0.32 |

| Clark et al. (2021) | China | 7 | −0.22 |

| Vegas (2022) | Colombia | 40 | −0.20 |

| Korbel and Prokop (2021) | Czech Republic | 9 | −0.11 |

| Birkelund and Karlson (2021) | Denmark | 22 | 0.00 |

| Schult et al. (2021) | Germany | 10 | −0.08 |

| Ludewig et al. (2022) | Germany | 10 | −0.14 |

| Depping et al. (2021) | Germany | 8 | −0.03 |

| Contini et al. (2021) | Italy | 15 | −0.19 |

| Asakawa and Ohtake (2021) | Japan | 11 | 0.00 |

| Hevia et al. (2021) | Mexico | 48 | −0.56 |

| Engzell et al. (2021) | Netherlands | 8 | −0.08 |

| Haelermans et al. (2021) | Netherlands | 10 | −0.17 |

| Schuurman et al. (2021) | Netherlands | 8 | −0.09 |

| Meeter (2021) | Netherlands | 10 | 0.00 |

| van der Velde et al. (2021) | Netherlands | 10 | 0.00 |

| Skar et al. (2021) | Norway | 7 | −0.24 |

| Jakubowski et al. (2022) | Poland | 20 | −0.30 |

| Chaban et al. (2022) | Russia | 14 | −0.27 |

| Ardington et al. (2021) | South Africa | 22 | −0.22 |

| Arenas and Gortazar (2022) | Spain (Basque country) | 12 | −0.05 |

| Tomasik et al. (2020) | Switzerland | 8 | −0.20 |

| Education Policy Institute (2021) | United Kingdom (England) | 10 | −0.09 |

| UK Department of Education (2021) | United Kingdom | 18 | −0.17 |

| Blainey and Hannay (2021) | United Kingdom | 9 | −0.08 |

| Rose et al. (2021) | United Kingdom | 13 | −0.16 |

| Kuhfeld et al. (2022) | USA | 28 | −0.19 |

| Kogan and Lavertu (2021) | USA | 25 | −0.23 |

| Pier et al. (2021) | USA (California) | 25 | −0.10 |

| Dependent Variable: Effect of School Closures on Student Test Score in Terms of Standard Deviation | |

|---|---|

| School closure less than 13 weeks | −0.012 *** |

| (0.002) | |

| School closure equal to or more than 13 weeks | −0.009 *** |

| (0.001) | |

| Adjusted R-squared | 0.26 |

| Number of observations | 36 |

| 1st Scenario (12-Week Closure) | 2nd Scenario (38-Week Closure) | 3rd Scenario (76-Week Closure) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Country examples in line with the scenarios | CHE, ISL | GRC, DEU, ITA, LTU, SVK | CHL, KOR, MEX |

| Mean years of schooling (in school year) | −0.32 | −1.00 | −2.00 |

| PISA score (in standard deviation) | −0.14 | −0.37 | −0.72 |

| Human capital (in %) | −0.16 | −0.45 | −0.87 |

| Dependent Variable: Logged Multi-Factor Productivity | Long Run | Short Run |

|---|---|---|

| Constant | −2.463 | |

| ETCR indicator | −0.041 ** | −0.140 ** |

| Trade openness (adjusted for country size) divided by 100 | 0.114 ** | 0.044 ** |

| Business expenditures on R&D (% of GDP) | 0.080 ** | n.s. |

| log(Human capital stock) | ||

| Population aged 16–39 | 2.359 ** | 1.426 * |

| Error correction term | −0.049 ** | |

| Adjusted R-squared | 0.960 | |

| Number of observations | 524 | |

| Number of countries | 32 | |

| Time fixed effects | NO | |

| Country fixed effects | YES |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

de la Maisonneuve, C.; Égert, B.; Turner, D. Quantifying the Macroeconomic Impact of COVID-19-Related School Closures through the Human Capital Channel. Economies 2023, 11, 289. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies11120289

de la Maisonneuve C, Égert B, Turner D. Quantifying the Macroeconomic Impact of COVID-19-Related School Closures through the Human Capital Channel. Economies. 2023; 11(12):289. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies11120289

Chicago/Turabian Stylede la Maisonneuve, Christine, Balázs Égert, and David Turner. 2023. "Quantifying the Macroeconomic Impact of COVID-19-Related School Closures through the Human Capital Channel" Economies 11, no. 12: 289. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies11120289

APA Stylede la Maisonneuve, C., Égert, B., & Turner, D. (2023). Quantifying the Macroeconomic Impact of COVID-19-Related School Closures through the Human Capital Channel. Economies, 11(12), 289. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies11120289