1. Introduction

China and Brazil established diplomatic relations in 1974 and formally established a strategic partnership in 1993. The partnership was upgraded to a comprehensive strategic partnership in 2013, making Brazil the first developing country to establish a comprehensive strategic partnership with China (

Cardoso 2013;

Santoro 2022;

Feng and Huang 2014). In 2014, the heads of state of the two countries unanimously expressed that they would further deepen the China-Brazil strategic partnership. 2023 marks the 30th anniversary of establishing the strategic partnership between China and Brazil and the 10th anniversary of the comprehensive strategic partnership. Brazilian President Lula successfully visited China in April 2023. The two countries issued a Joint Statement on Deepening the Comprehensive Strategic Partnership, indicating that China-Brazil’s bilateral economic and trade cooperation ushered in a new opportunity and that deepening the bilateral economic and trade cooperation in various fields has become a consensus. While planning for the future development of both China and Brazil, a review of the economic and trade cooperation between China and Brazil will help us to better look into the future. From 2012 to 2022, China and Brazil have made significant progress in trade in goods, with bilateral cooperation in trade in goods expanding, the cooperation mechanism deepening, the development of the bilateral relationship gaining momentum, and the remarkable effect of cooperation in various fields. As one of the noteworthy emerging markets in the global economy, Brazil is widely regarded by the international community as one with tremendous development potential in the 21st century (

Chant and McIlwaine 2009). Since China surpassed the United States to become Brazil’s top trading partner and export destination in 2009 and Brazil’s top source of imports in 2012, China has remained Brazil’s top trading partner, the top source of imports, and the top export destination for 14 consecutive years (

Santoro 2022). Bilateral trade increased from

$83.33 billion in 2013 to

$17.14 billion in 2022. Bilateral trade has grown from US

$83.33 billion in 2013 to US

$171.49 billion in 2022, a year-on-year increase of 105.79% in ten years, with the total amount of bilateral trade expanding and the trade structure continuing to be optimized.

Generally speaking, bilateral trade and economic development are gaining momentum, and with the consolidation and enhancement of Brazil’s position in the global market and the complementary position of China and Brazil in resources and industries, China and Brazil have broad prospects for economic and trade development. However, it should also be recognized that China-Brazil’s trade in goods still faces specific problems. Trade friction between the two countries is prominent, and the degree of bilateral trade integration needs to be improved. Along with China’s proposal to build a new development pattern of double-cycle, on the occasion of the 10th anniversary of the establishment of China-Brazil Comprehensive Strategic Partnership, a review of the current situation, problems and opportunities of China-Brazil economy and trade in the past ten years will help to consolidate further and develop China-Brazil bilateral cooperation in various fields, and will be of great value to the understanding of the importance and exemplary role of China-Brazil economic and trade co-operation.

2. Literature Review

Since the establishment of diplomatic relations between China and Brazil in 1974, bilateral cooperation in various fields has been continuously upgraded. Cooperation in economy, culture, education, and other areas has achieved remarkable results, forming a relatively close bilateral and multilateral economic and trade cooperation. Since the 21st century, along with the profound changes in the international political and economic landscape, especially since the financial crisis of 2008, the world’s economic development has been uncertain. Since then, the world economy has experienced a decade-long adjustment phase until 2017, when it gradually recovered. A century-old epidemic in 2019 once again cast a haze over the world’s economic recovery (

Aktar et al. 2021;

Chen et al. 2019). As the world’s major emerging market countries and regional powers, China and Brazil play a crucial role in the recovery of the world economy and the adjustment of the international political and economic pattern, and China and Brazil have a wide range of common interests in the field of economic and trade cooperation. Cooperation in trade and economic cooperation plays the role of “ballast” for the sustained and solid development of China-Brazil relations.

Further deepening bilateral economic and trade cooperation has gradually become a bilateral consensus. In the post-pandemic period, when the world economy is weak and growth is sluggish, recovery and development depend on deepening economic and trade cooperation among countries worldwide. It is impractical to rely solely on a particular country. China-Brazil economic and trade cooperation has provided a model for South-South cooperation while promoting the recovery of the world economy (

Singh Puri 2010).

The influencing factors of inter-country trade are diverse. Numerous studies have found that geographic distance between countries, trade convenience, trade complementarity, competitiveness, national economy size, and infrastructure conditions are essential factors affecting inter-country trade.

Nitsch (

2000) analyzed inter-country trade between EU countries from the point of view of the geographic distance between countries using the trade gravity moh line and found that the national borders had significant, if not decisive, impacts on trade.

Borchert and Yotov (

2017) also analyzed the relationship between globalization and international trade from a distance perspective. Based on the trade data of 86 countries from 1986 to 2006, they discussed and proposed the “distance problem” in international trade. “The study found that the impact of distance has declined along with the development of globalization, while the impact of proximity and regional trade agreements has increased over time. This precisely reflects the increasingly close regional economic cooperation that characterizes the current development of the world economy. Human and geographic differences between countries also affect the level of inter-country trade. For example,

Hutchinson (

2005), from the perspective of “linguistic distance”, through the 36 non-English-speaking countries in international trade analysis, found that in the same or similar language countries, the level of trade was higher. Whereas the level of international trade often faces multiple constraints in countries with different languages. The post-World War II intensification of trade between Japan and the United States and between South Korea and the United States are just a few examples. In addition to this,

Carrère and Schiff (

2005),

White and Tadesse (

2008), and

Gallego and Llano (

2014), amongst others, have also examined the perspective of the distance between countries.

The level of trade facilitation is another essential factor affecting trade between countries.

Hoekman and Nicita (

2011) studied developing countries’ trade from the perspective of trade costs and trade policies, and while traditional trade policies are still important in developing countries and some sectors in high-income countries, non-tariff measures and domestic trade costs are also important. The level of trade facilitation is essential to developing countries’ trade.

de Sá Porto et al. (

2015), on the other hand, based on trade data for 72 countries in 2011 and 2012, using a gravity model, analyzed and found that trade facilitation measures contribute to the improvement of trade performance in countries around the world.

Chimilila et al. (

2014) focused on the effect of trade facilitation measures on trade in the context of the EAC Customs Union on Tanzania’s trade; the study found that trade performance, foreign direct investment (FDI) inflows, and trade tax revenues improved significantly in all EAC countries as a result of trade facilitation initiatives. At the same time, the main obstacles to trade facilitation are non-tariff barriers, transport infrastructure, inadequate human resource capacity, and low levels of automation. The level of trade facilitation is of a more significant concern than the differences in natural and human geography between countries.

Trade competitiveness and complementarity are essential indicators for analyzing the degree of trade closeness between countries. They are also essential indicator factors for the level of trade in goods between China and Brazil in this paper.

Chen et al. (

2020) empirically analyzed the impact of trade competitiveness and complementarity on the development of China’s trade with countries along the Belt and Road. They found that factors such as land area, trade complementarity, common language, and free trade agreements (FTAs) between China and countries along the Belt and Road significantly contributed to China’s trade with these countries. It is found that factors such as land area, trade complementarity, common language, and free trade agreements (FTAs) between China and the countries along the “Belt and Road” significantly promote the development of trade between China and the countries along the “Belt and Road.” Whereas geographic distance and trade competitiveness between countries significantly inhibit the development of trade between China and the countries along the “Belt and Road”.

This also confirms the influence of geographical factors on inter-country trade.

Tang et al. (

2023) conducted a comparative analysis of China’s bilateral trade relations with the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) and the European Union (EU) from the perspectives of the total volume and structure of trade, the index of trade complementarity, and the influencing factors of bilateral trade flows, to develop a reasonable understanding of China’s trade relations with ASEAN and the EU. A series of studies have confirmed the value of trade complementarity and competitiveness analyses in understanding inter-country trade relations, with trade complementarity reflecting the complementary advantages of inter-country trade and trade competitiveness reflecting the competitive relationship between countries trading different types of commodities, which can help to coordinate the types of commodities traded between countries, thus promoting the sustainable development of inter-country trade (

Armstrong 2007;

Baumann and Ng 2012;

Bojnec and Fertő 2012).

National market size is also often an essential factor scholars use to study international trade.

Clegg et al. (

2003) studied the impact of the national market size from the perspectives of regional economic integration and FDI in a globalized economy. They found that the national market size is directly related to the development of regional economic integration and the absorption of FDI.

Di Giovanni and Levchenko (

2012) proposed a new mechanism by which country size and international trade affect macroeconomic fluctuations, while

Alesina et al. (

2005) pointed out that market size has an impact on economic growth based on analyzing the relationship between country size and international relations, and at the same time pointed out the endogenous determinants of national market size on economic growth.

Amiti and Wakelin (

2003) explored the relationship between investment liberalization and international trade by qualifying the factor of national market size. They pointed out that the impact of reducing the cost of FDI on exports depends on the country’s characteristics and the cost of trade. There is a positive correlation between the level of investment liberalization and international trade for the same market size.

Keshk et al. (

2010) focus on the trade and conflict relationship. The size of the conflict is closely related to the distance between countries and the size of the national market. The study, through the analysis of geographic proximity, the size of the national market, trade data, and so on, found that there is no inevitable relationship between the development of trade and peace, and peace between the countries helps to promote the development of trade, and the conflict reduces the trade.

More scholars have focused on the close relationship between infrastructure and inter-country trade. A study by

Behrens et al. (

2018) reveals the role of international trade in national infrastructure. The study analyses its impact on national economies in economic integration and finds that trade liberalization in developing countries with weak infrastructures and mostly self-sufficient regions is likely to exacerbate spatial inequalities. In contrast, countries with better infrastructure and more significant interregional trade will likely achieve more balanced spatial development by redistributing economic activities, whether better or worse infrastructure conditions are often associated with trade facilitation and trade costs.

Donaubauer et al. (

2018) assess the impact of infrastructure on bilateral trade between developed and emerging economies from 1992–2011. They concluded that improved infrastructure reduces the costs of international trade and increases international trade flows and that better infrastructure is more conducive to the development of international trade.

Similarly,

Lorz (

2020) analyses the relationship between infrastructure and the level of trade. In contrast to the former study, which analyses the impact of the presence of infrastructure on the level of trade, the study takes the opposite side. It analyses the impact of investment in infrastructure on trade. The study concluded that improvements in transport infrastructure reduce the cost of transport. Governments decide on the investment in their respective countries in a non-collaborative way. Exporting countries whose producers benefit from lower transport costs spend more on infrastructure than importing countries, and producers in importing countries are protected from foreign competition by transport costs. In sum, infrastructure development and the level of international trade show a close correlation, with higher levels of infrastructure facilitating trade.

3. Factual Characteristics of Trade in Goods between China and Brazil

3.1. Continued Rise in Total Trade in Goods between the Two Countries

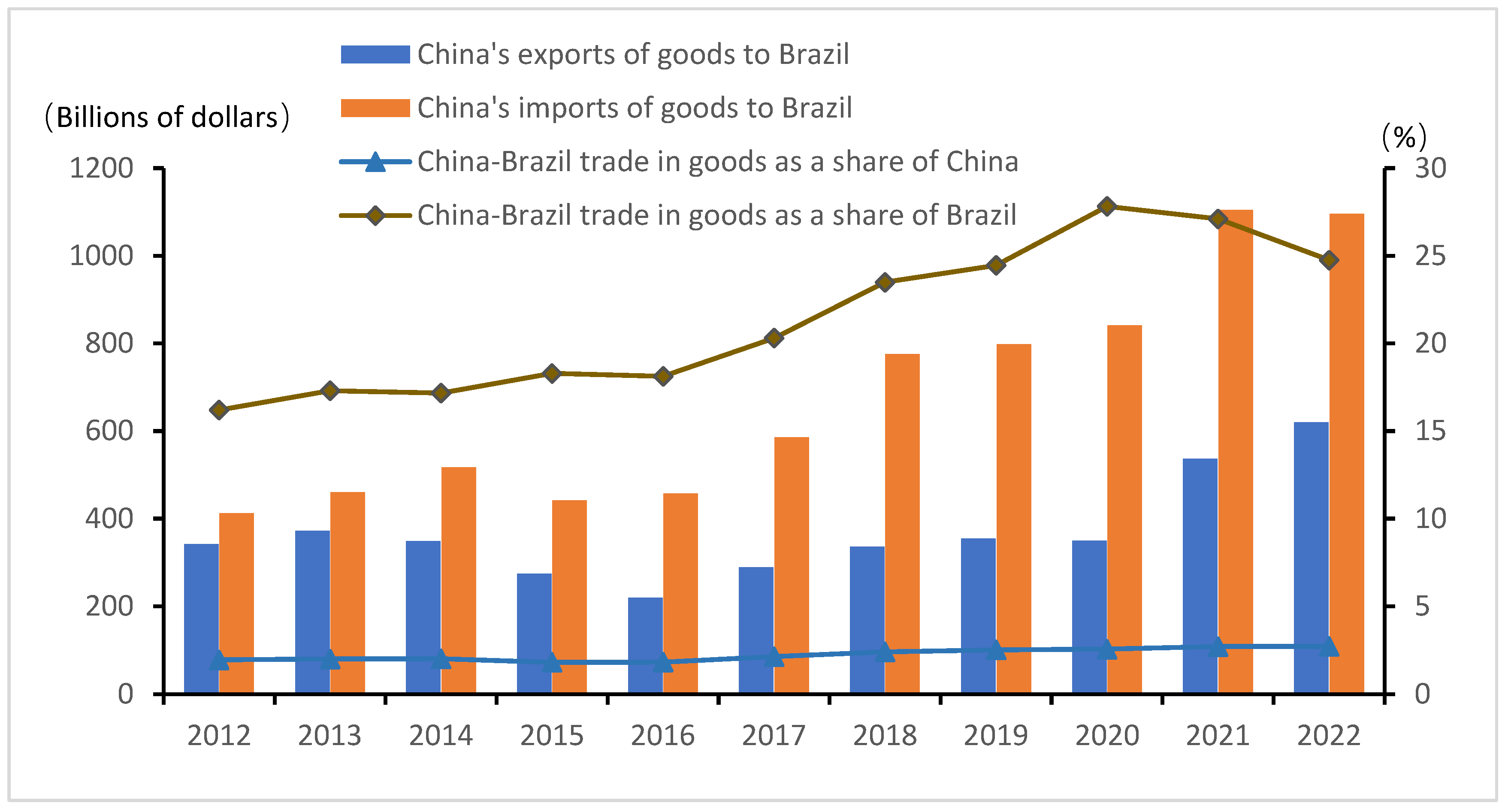

Since establishing the comprehensive strategic partnership between China and Brazil, the total volume of bilateral economic and trade between China and Brazil has increased significantly. In terms of total bilateral trade in goods, China has consistently ranked as Brazil’s top trading partner over the past ten years, with bilateral trade in goods between the two countries growing from US

$75.48 billion in 2012 to US

$171.49 billion in 2022 (see

Figure 1), with an average annual growth rate of 7.75 percent, which is much higher than the average annual growth rate of trade between China and the United States (3.84 percent), China and South Korea (4.7 percent), and China and Japan (1.35 percent) over the same period—the average annual growth rate of China’s external bilateral trade.

In terms of the development of bilateral trade, it is roughly divided into three phases: a stable growth phase (2013–2014), a recessionary period (2015–2016), and a period of rapid development (2017–2022). The global economic development bottomed out in 2012. However, China’s trade and economic development has not been significantly affected by the impact of Brazil’s total imports and exports of goods in 2013, which still maintains a growth trend. According to China Customs data, the total bilateral trade in goods between China and Brazil was US$75.48 billion in 2012, with a year-on-year increase of 10.4 percent, compared with 2012. The downturn in the development of the world economy and the sluggish economic growth of major global economies affected 2015–2016. The bilateral trade in goods between China and Brazil was affected by the stagnation of the international financial crisis, with the total volume of trade in goods showing a downward trend, and 2016 was the lowest point of total trade in goods between China and Brazil in the past ten years, with only US$1.5 billion. In 2016, the total trade in goods between China and Brazil was at its lowest point in a decade, only US$67.16 billion, a decrease of 19.4% compared with 2013. Since 2017, the bilateral trade in goods between China and Brazil has stabilized and improved. The total bilateral trade in goods between China and Brazil has significantly increased, recovering to the level of the world economy before the fluctuation in 2017 to reach US$87.54 billion, with an average annual growth rate of 14.59% in the five years after that, and the total bilateral trade in goods between China and Brazil in 2018 exceeded US$100 billion for the first time. Total bilateral trade in goods between China and Brazil exceeded US$100 billion for the first time, reaching US$111.18 billion, and total bilateral trade in goods between China and Brazil reached US$171.49 billion by 2022, a year-on-year growth of 105.79 percent over a decade.

Regarding trade balance, China, the world’s top trade surplus country, will have an annual trade surplus of

$877.6 billion in 2022, 2.63 times higher than Russia, the second-largest (

$333.4 billion). However, in China-Brazil bilateral trade in goods, China consistently maintains a large trade deficit, with a deficit of

$8.73 billion in 2013, a deficit of the decade’s highest peak of US

$56.84 billion in 2021, and a deficit of US

$47.55 billion in 2022. From the point of view of the share of bilateral trade in goods, the share of China-Brazil bilateral trade in goods in China’s import and export trade in goods during the decade increased from 2% in 2003 to 2.72% in 2022 (see

Figure 1), with minor changes, basically maintaining the external 2.5 or so. In contrast, China-Brazil bilateral trade in goods accounted for a larger share of Brazil’s import and export trade in goods. It grew from 17.3% in 2013 to 27.82% in 2020 and 27.1% in 2021. The share in 2022 dropped slightly to 24.75% compared with the previous year, showing that China’s position as the top source of imports and the destination of exports in Brazil over the past ten years is accompanied by a significant development in the total bilateral trade in goods between China and Brazil.

3.2. Diversification of Trade Structure

Regarding the composition of bilateral trade in goods, the commodity composition is relatively concentrated. China’s imports from Brazil are mainly concentrated in the four categories of SITC2 (non-edible raw materials), SITC3 (mineral fuels, lubricating oils, and related raw materials), SITC6 (manufactured goods classified according to raw materials), and SITC7 (machinery and transport equipment). The above four categories accounted for 91.74 percent of China’s imports from Brazil in 2012. It decreased to 89.61 percent in 2022. However, they are still the main category of China’s imports from Brazil, with the share of non-food raw materials, including ores, consistently remaining between 64% and 81% (see

Table 1). Brazil’s imports from China are mainly concentrated in the four categories of SITC5 (chemicals and related products), SITC6, SITC7, and SITC8 (miscellaneous products), which accounted for 97.17 percent of China’s exports to Brazil in 2012. They dropped to 96.82 percent in 2022, with machinery and transport equipment occupying a long-term position as the primary commodity, with a share of 40–50 percent (see

Table 1). 40–50% (see

Table 2). Overall, China’s imports from Brazil are mainly primary products, with resource-intensive products occupying the central position and the proportion of capital-technology-based products rising slightly but not significantly. China’s exports to Brazil are mainly manufactured goods, with capital-technology-based and labor-intensive products occupying an absolute position. The data shows that the structure of China-Brazil trade in goods continues to optimize simultaneously. However, the problem of imbalance in the structure of import and export commodities is still more significant. From the perspective of the technical content of products, China’s imports of goods from Brazil are generally low-tech products. China’s exports to Brazil are mostly medium-tech and high-tech products.

According to China Customs data, the composition of China-Brazil’s import and export commodities is further analyzed at the HS code level. In 2022, China’s exports to Brazil mainly consisted of electromechanical and audio-visual types of equipment and their parts and accessories in category 16 (42%), products of the chemical industry and its related industries in category 6 (21%), base metals and their products in category 15 (8%), raw materials for textiles and textile products in category 11 (7%), and vehicles, aircraft, ships, and transport equipment in category 17 (4%). Seventeen vehicles, aircraft, ships, and transport equipment (4%), etc., in 2022, China’s imports from Brazil will mainly consist of mineral products in Category 5 (42.37%), plant products in Category 2 (34.19%), animal products in Category 1 (9.29%), cellulosic pulp, wastepaper, paper, cardboard and products thereof in Category 10 (5.69%) and base metals and products thereof (1.75%) etc. According to the SITC code data and HS code data, it can be found that the product structure of China’s imports from Brazil and China’s exports to Brazil is distinctive. Although there are two-way imports and exports of some commodities, which show a certain degree of intra-industry trade, the proportion of this part of the products in the total amount of imported and exported goods of China and Brazil is insignificant. It cannot be considered that the trade of goods between China and Brazil shows the characteristics of intra-industry trade.

Regarding the difference in specific categories of goods, the HS code includes 22 categories and 98 chapters of commodity classification. In 2015, the China-Brazil trade in goods contained 22 categories and 97 chapters of commodity classification. Thirty (30) chapters of commodities were in a deficit position, of which the most significant deficit was for the minerals, a deficit of 17.945 billion U.S. dollars. In 2022, China-Brazil trade in goods, in a position of deficit in the commodity sector, has increased significantly. There are 71 chapters in a trade deficit position and only 27 items in a surplus position. The import and export balance of mineral products expanded to $45.69 billion, compared with 2015 year-on-year growth of 154.6%. Commodities that account for a significant share of China-Brazil trade in goods imports and exports are separate from the import and export sides. China’s exports are dominated by manufactured goods such as light industry and machinery and equipment. In contrast, primary products dominate imports, and there is a significant difference between imported and exported commodities, which shows a strong complementarity.

5. Conclusions and Limitations of Trade in Goods between China and Brazil

5.1. Conclusions

The article selects establishing a comprehensive strategic partnership between China and Brazil in 2012 as the time point. It selects the data on the trade in goods between China and Brazil from 2012 to 2022 to form a perfect analysis of the competitiveness and complementarity of the trade in goods between China and Brazil under the comprehensive strategic partnership. On the one hand, from the perspective of the factual characteristics of the trade in goods between China and Brazil, it is found that the trade in goods between China and Brazil presents two main features, one of which is the continuous rise in the total trade in goods, which has increased from US$75.48 billion in 2012 to US$171.49 billion in 2022. Secondly, the structure of trade in goods between China and Brazil presents diversified characteristics, and the types of trade between the two countries are becoming increasingly prosperous. On this basis, with the help of the international trade analysis method, China and Brazil’s trade in goods is empirically analyzed to explore the competitiveness and complementarity of the trade in goods between the two countries to draw the following conclusions:

First, from the perspective of the explicit comparative advantage index of goods trade between the two countries, China and Brazil have advantages in different types of goods. China’s exports of manufactured goods to Brazil have a more tremendous comparative advantage than Brazil’s exports of manufactured goods to China. In contrast, Brazil’s exports of primary products to China have a more tremendous comparative advantage than China’s exports of primary products to Brazil. Therefore, in the import and export of goods trade between the two countries, each has the corresponding comparative advantage.

Secondly, the competitive advantage index of the two countries’ trade in goods and the two countries’ explicit comparative advantage index of trade in goods show the same characteristics. In the bilateral trade between the two countries, China has a more competitive advantage in the manufactured goods category. Brazil has a more competitive advantage in the category of primary products due to the limitation of China’s primary product reserves and the difficulty of exploitation.

Again, from the point of view of the goods trade integration index of the two countries, the two countries have a close relationship in the trade in goods. Along with the continuous deepening of the economic and trade cooperation between the two countries, the two countries’ trade in goods is becoming increasingly close.

Finally, from the index of the complementarity of trade in goods between the two countries, the complementarity between China and Brazil is evident. On the one hand, due to the limitations of China’s reserves and difficulties in exploiting primary products, China’s primary product shortage is significant. Brazil’s primary product exports to China effectively make up for China’s development of the primary products needed. On the other hand, China’s advantages in manufactured products effectively make up for the weakness of its industry caused by the manufactured products in Brazil. On the other hand, China’s advantage in industrially manufactured goods effectively compensates for Brazil’s lack of manufactured goods caused by its industrial weakness.

Overall, China and Brazil have a close relationship in trade in goods. Since the establishment of the comprehensive strategic partnership between the two countries, the total volume and structure of trade in goods between the two countries have achieved remarkable development. The competition and complementarity of trade in goods between the two countries coexist. However, the complementarity of trade in goods between the two countries is much greater than the competition, and deepening the cooperation in trade in goods between the two countries is conducive to the long-term development of the relationship between China and Brazil.

5.2. Limitation

The article mainly analyses the current situation of goods trade cooperation between China and Brazil from the perspective of the goods trade data of the two countries to form a comprehensive and complete study on the development of goods trade between the two countries. However, the study still has certain limitations, mainly including two aspects. Firstly, the data sources of the study are scattered. The data on China and Brazil’s trade in goods come from the United Nations Trade Database, China Customs, and the official website of Brazil’s Ministry of Economy. However, some things could be improved in the statistical methods of different countries and organizations. There are also differences in the types of currencies, so there are some data defects in calculating the total volume of trade in goods and the specific volume of trade in goods. Of course, this is unavoidable in international trade research, so we try to minimize the errors caused by different data sources. Secondly, the article is mainly based on the two aspects of competition and complementarity on the empirical study of China and Brazil’s trade in goods to analyze the current situation of trade in goods for the impact of China and Brazil’s trade in goods of the two countries are not enough.

Therefore, because of the two limitations of the study, it is hoped that subsequent researchers can further study on this basis. Regarding data processing, the analysis error caused by data collation and arithmetic should be reduced as much as possible. In contrast, the research plan should include an analysis of the influencing factors of the trade in goods between China and Brazil. The analysis should be carried out from the perspectives of politics, economy, strategic planning, and policies to provide more accurate suggestions for deepening the cooperation in the trade of goods between the two countries.