Empirical Analysis of Demand for Sukuk in Uzbekistan

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

3. Methodology

3.1. Ordered Logit Regression

3.2. Data

4. Empirical Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistics of Variables and Visual Analysis of Demand for Waqf-Based IMF

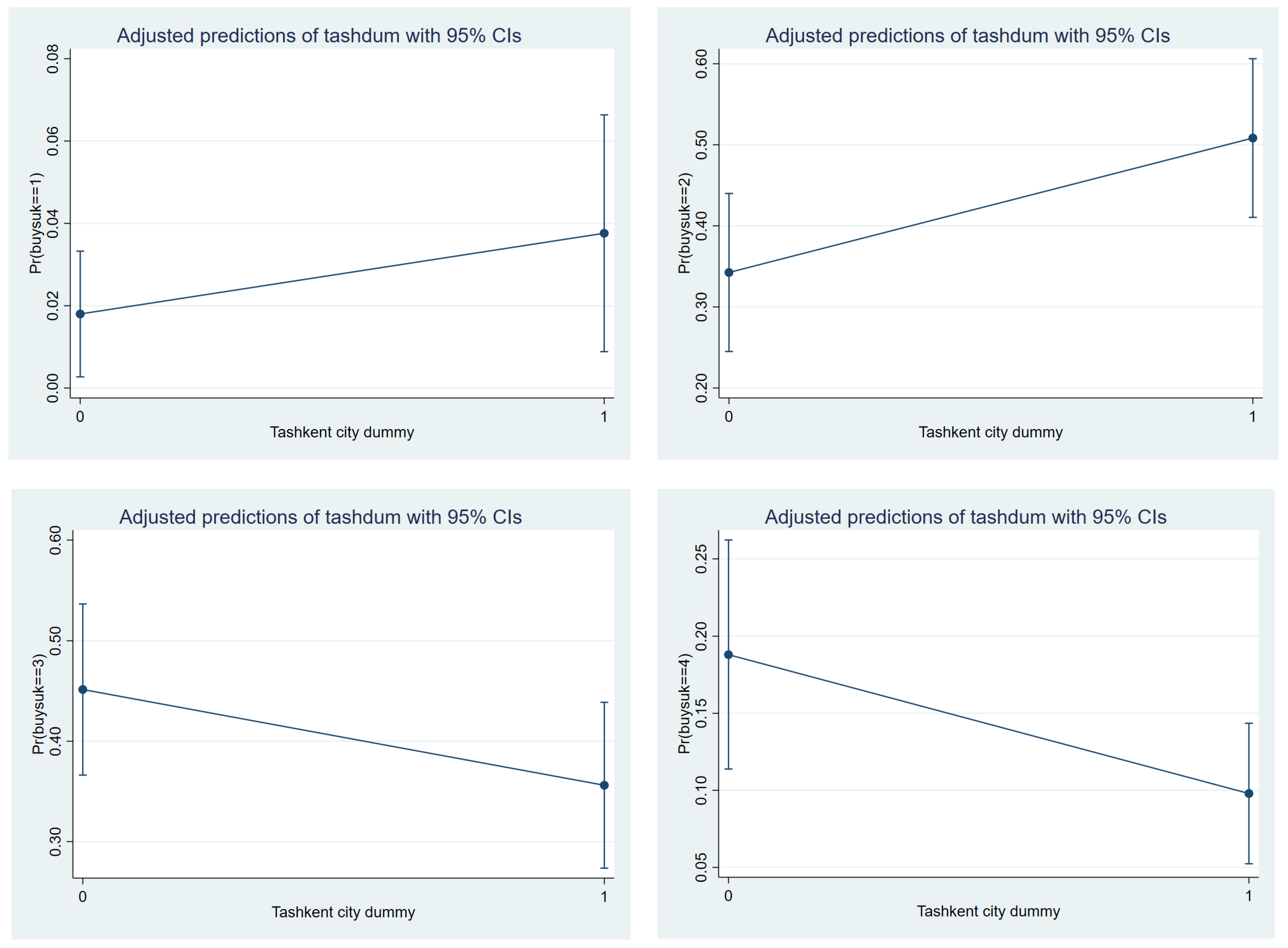

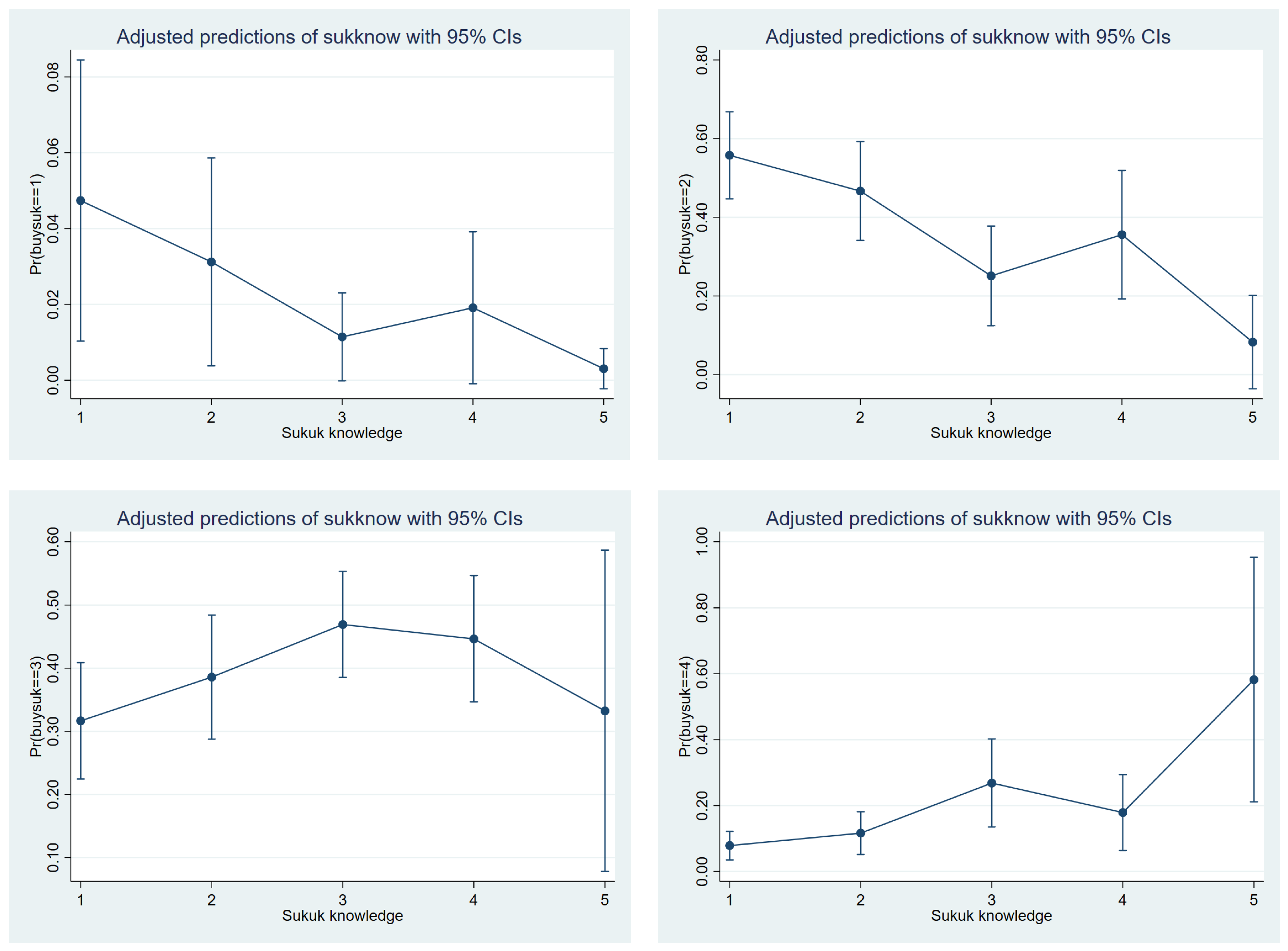

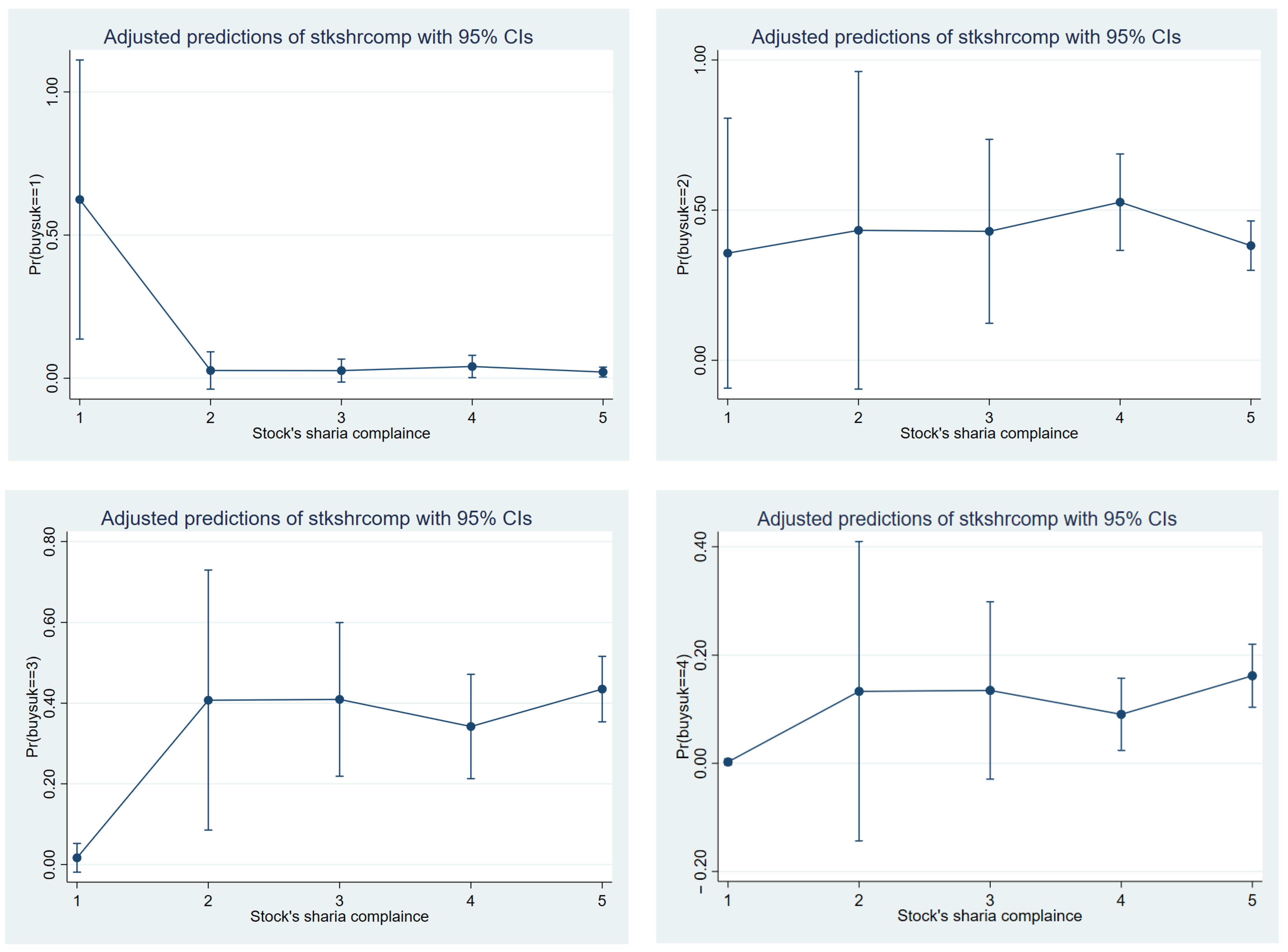

4.2. Margin Plot Analysis

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

6.1. Summary of Findings

6.2. Policy Recommendations

- ▪

- Firstly, as previous studies found, it is important to provide a favorable legal infrastructure for the issuance of sukuk by making necessary changes to the capital market regulations in Uzbekistan (Asadov et al. 2023, 2024). These changes should make the investment and issuance of sukuk legal in the country.

- ▪

- Reflecting the high demand for sukuk among the population, the government and businesses should seriously consider issuing Islamic securities. Once the necessary legislative changes are made, more sukuk can be issued for both local and international investors.

- ▪

- Practitioners should focus on specific segments of Uzbekistan’s population that show the highest potential to invest in sukuk. These include residents of regions other than the capital city, individuals with some investing experience and knowledge of sukuk, and those with a strong preference for Shari’ah-compliant investments.

- ▪

- Considering the importance of knowledge of sukuk and investing experience, both issuers of sukuk and government organizations should focus on disseminating knowledge about sukuk among the public. Additionally, promoting investment experience through mobile apps or online simulations would also enhance demand for sukuk in Uzbekistan.

6.3. Limitations of the Study and Avenues for Future Research

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Distribution of Categorical Independent Variable

| Dependent Variable | Intent to Buy sukuk if Offered in Uzbekistan | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable Names | Variable Category | Will Not Buy (1) | Maybe Will Buy (2) | Probably Will Buy (3) | Definitely Will Buy (4) | Total |

| Capital market knowledge (cmknow) | very familiar (5) | 0.00 | 2.55 | 1.02 | 2.04 | 5.61 |

| familiar (4) | 0.51 | 4.59 | 12.24 | 3.06 | 20.41 | |

| some knowledge (3) | 2.04 | 11.73 | 14.80 | 5.61 | 34.18 | |

| little knowledge (2) | 1.02 | 13.78 | 7.65 | 3.06 | 25.51 | |

| not familiar (1) | 1.53 | 7.65 | 0.51 | 4.59 | 14.29 | |

| Experience investing in securities (invexpr) | do regularly (5) | 0.00 | 0.51 | 0.51 | 1.02 | 2.04 |

| some experience (4) | 1.02 | 3.57 | 7.14 | 4.08 | 15.82 | |

| knowledge no experience (3) | 1.02 | 11.73 | 13.78 | 5.10 | 31.63 | |

| no knowledge but interested (2) | 0.51 | 14.80 | 11.22 | 6.12 | 32.65 | |

| no experience not interest (1) | 2.55 | 9.69 | 3.57 | 2.04 | 17.86 | |

| Sukuk knowledge (sukknow) | very familiar (5) | 0.00 | 0.51 | 1.02 | 2.55 | 4.08 |

| familiar (4) | 0.00 | 3.57 | 8.16 | 2.04 | 13.78 | |

| some knowledge (3) | 0.00 | 3.57 | 8.67 | 4.59 | 16.84 | |

| little knowledge (2) | 0.51 | 12.24 | 9.69 | 2.55 | 25.00 | |

| not familiar (1) | 4.59 | 20.41 | 8.67 | 6.63 | 40.31 | |

| Islamic stock knowledge (ismstkknow) | very familiar (5) | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.51 | 0.51 |

| familiar (4) | 0.00 | 1.02 | 5.10 | 2.55 | 8.67 | |

| some knowledge (3) | 0.00 | 5.61 | 9.18 | 5.10 | 19.90 | |

| little knowledge (2) | 0.51 | 14.80 | 10.71 | 4.59 | 30.61 | |

| not familiar (1) | 4.59 | 18.88 | 11.22 | 5.61 | 40.31 | |

| Stock’s Shari’ah compliance (stkshrcomp) | very important (5) | 3.57 | 28.57 | 29.08 | 15.82 | 77.04 |

| Important (4) | 0.00 | 7.65 | 5.10 | 2.04 | 14.80 | |

| relatively important (3) | 0.00 | 2.04 | 1.53 | 0.51 | 4.08 | |

| not very important (2) | 0.00 | 1.02 | 0.51 | 0.00 | 1.53 | |

| not important at all (1) | 1.53 | 1.02 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 2.55 | |

| Grand total | Percentage | 5.10 | 40.31 | 36.22 | 18.37 | 100.0 |

| Count | 10 | 79 | 71 | 36 | 196 | |

Appendix B. Survey on the Prospects of Introducing sukuk Securities in Uzbekistan

- (1)

- Your age

- (a)

- 19 or younger

- (b)

- 20–29 years old

- (c)

- 30–39 years old

- (d)

- 40–49 years old

- (e)

- 50–59 years old

- (f)

- 60 and older

- (2)

- Your gender

- (a)

- Male

- (b)

- Female

- (3)

- Your marital status

- (a)

- Single

- (b)

- Married

- (c)

- Divorced

- (d)

- Widowed

- (4)

- Your place of residence (one of 14 regions or a foreign country)

- ▪

- Andijan region

- ▪

- Bukhara region

- ▪

- Ferghana region

- ▪

- Jizzakh region

- ▪

- Khorezm region

- ▪

- Namangan region

- ▪

- Navoi region

- ▪

- Qashqadarya region

- ▪

- Republic of Karakalpakstan

- ▪

- Samarkand region

- ▪

- Sirdarya region

- ▪

- Surkhandarya region

- ▪

- Tashkent region

- ▪

- Tashkent city

- ▪

- Foreign country

- (5)

- Field of your work

- (a)

- Banking–finance industry

- (b)

- Education (higher education, school, etc.)

- (c)

- Farming and agriculture

- (d)

- Production and construction

- (e)

- Public service

- (f)

- Trade or services industry

- (g)

- Other (please specify)

- (6)

- Your income level

- (a)

- Below 2 million som

- (b)

- Between 2 and 5 million som

- (c)

- Between 5 and 10 million som

- (d)

- Between 10 and 15 million som

- (e)

- Between 15 and 20 million som

- (f)

- Between 20 and 30 million som

- (g)

- Above 30 million som

- (7)

- How much do you know about the activities in the capital markets (stock markets)?

- (a)

- I am very familiar.

- (b)

- I am generally familiar.

- (c)

- I have some knowledge.

- (d)

- I have very little knowledge.

- (e)

- I am not familiar at all.

- (8)

- Do you have experience investing in financial securities (e.g., stocks, bonds, etc.)?

- (a)

- I do it regularly.

- (b)

- I have some experience investing in them.

- (c)

- I have a general understanding and interest but have not invested yet.

- (d)

- I do not think that I have enough experience and understanding, but I am interested.

- (e)

- I do not have any experience, and I am not planning to invest in them.

- (9)

- How much do you know about Islamic bonds (i.e., sukuk)?

- (a)

- I am very familiar.

- (b)

- I am generally familiar.

- (c)

- I have some knowledge.

- (d)

- I have very little knowledge.

- (e)

- I am not familiar at all.

- (10)

- How much do you know about Islamic stocks and stock indexes?

- (a)

- I am very familiar.

- (b)

- I am generally familiar.

- (c)

- I have some knowledge.

- (d)

- I have very little knowledge.

- (e)

- I am not familiar at all.

- (11)

- If you decide to invest in stocks, to what extent is their compliance with Shari’ah (i.e., being Halal) important for you?

- (a)

- Very important

- (b)

- Important

- (c)

- Relatively important

- (d)

- Not very important

- (e)

- Not important at all

- (12)

- Would you buy Islamic bonds (sukuk) if they were issued in Uzbekistan?

- (a)

- Yes, I would definitely buy them.

- (b)

- Probably, I most likely would buy them.

- (c)

- Probably, if they are in smaller denominations (e.g., 5–10 million som).

- (d)

- Maybe, depending on its type (structure and sharia contract).

- (e)

- Maybe, if sukuk provides more return than traditional bonds.

- (f)

- No, I would not buy them at all.

- (13)

- If you have any suggestions and feedback related to introduction and development of sukuk markets in Uzbekistan, please write them below.(Open-ended question)

| 1 | The method of stratified random sampling was used in our survey to ensure that none of the major segments (strata) of the population is underrepresented. Stratified random sampling combines the randomness of pure random sampling with the representativeness of stratified sampling (see Singh and Mangat 1996 for more details). For example, in our sample, we used gender (female dummy) and marital status (married dummy) among the independent variables. While sampling, we ensured that each of their strata (female vs. male or married vs. others) had at least 10% representation in the total sample size (see Table 1). For sample size determination, we followed the rule of thumb suggested by Peduzzi et al. (1996) for logistic regressions, which recommends at least 10 events per variable (EPV) to obtain unbiased regression coefficients. Our sample size of 196 meets this requirement for at least two out of the three models we estimated (see Table 4). Specifically, Model (2) requires a minimum sample size of 150, while Model (3) requires a minimum sample size of 130 observations. Although our sample size falls slightly short for Model (1) when counting each predictor parameter (beta), it overwhelmingly satisfies Model (3)’s requirement of a minimum of 130 observations for 13 predictor parameters, as suggested by Peduzzi et al. (1996). Since we chose Model (3) as our final model and the dropped variables from Models (1) and (2) were largely insignificant, our sample size of 196 is more than adequate. |

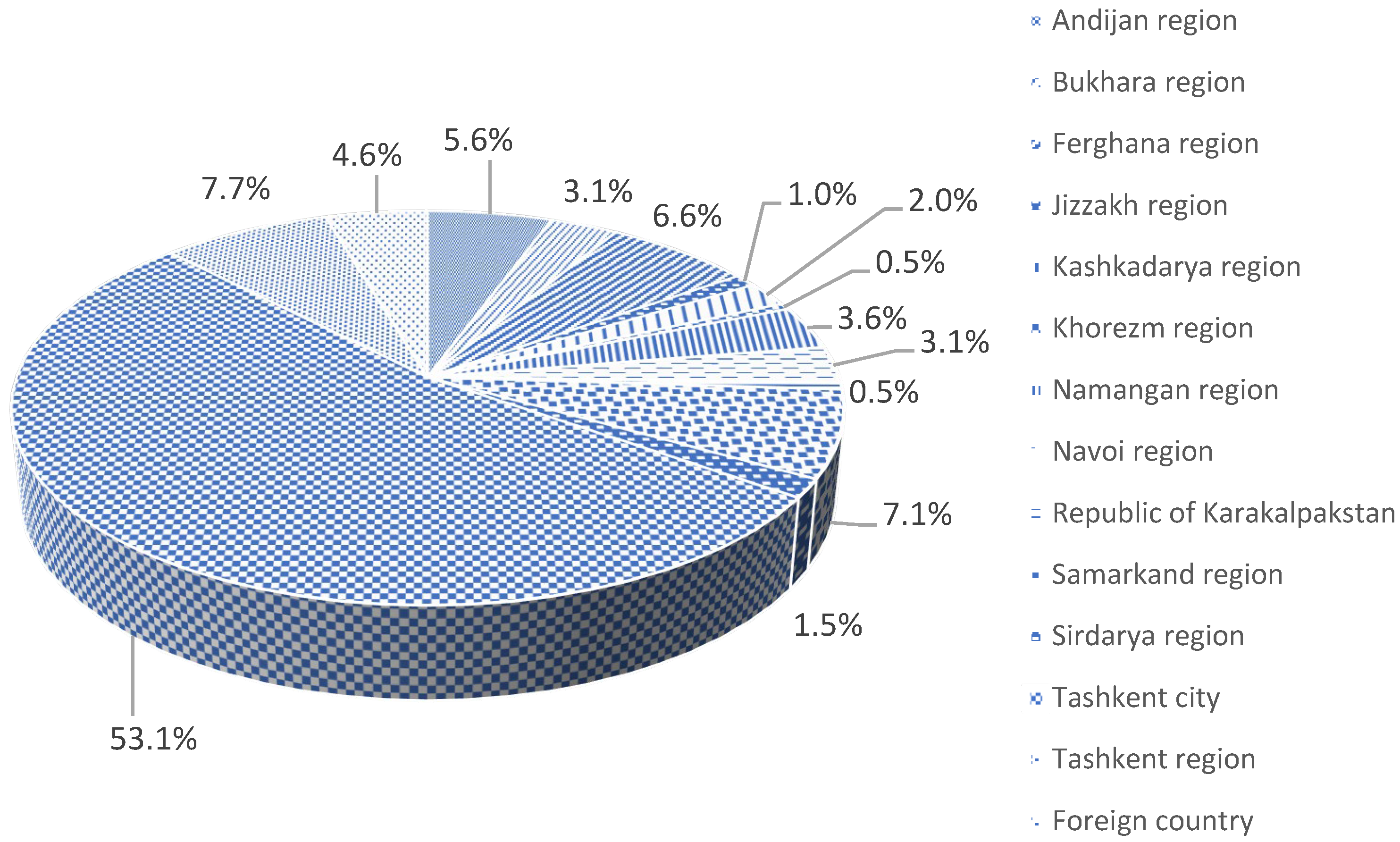

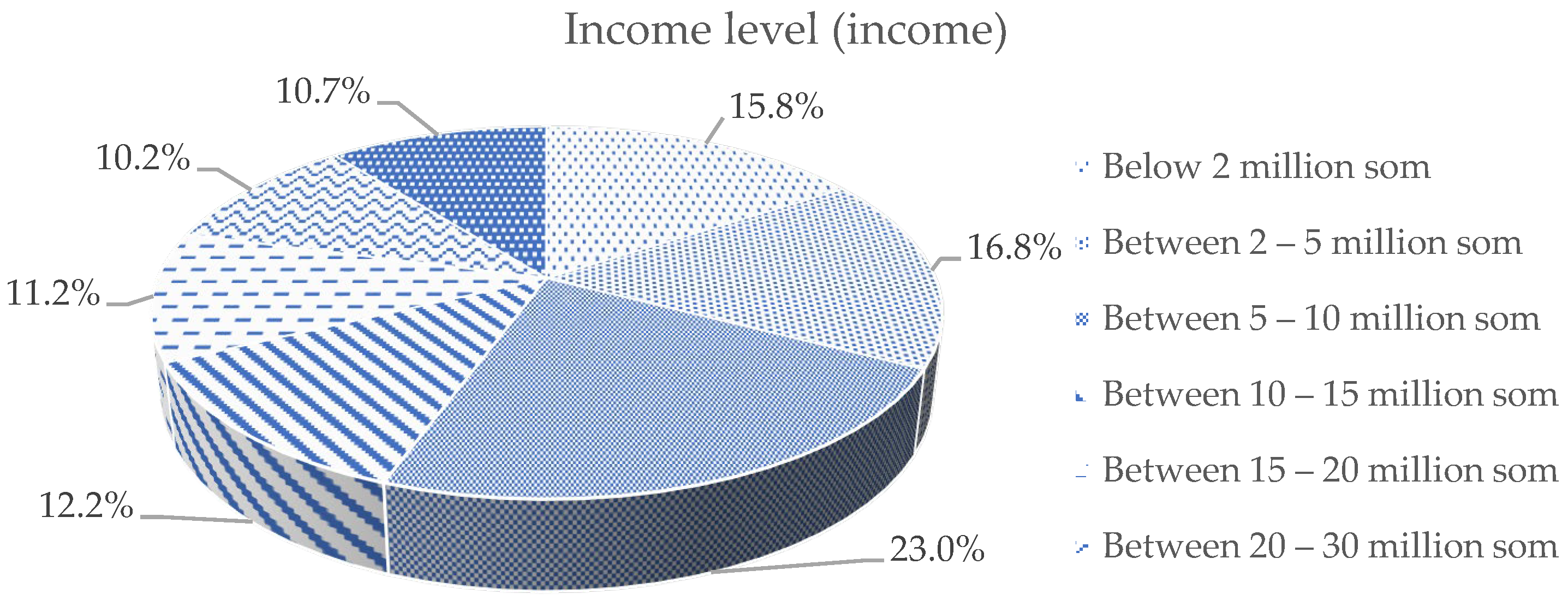

| 2 | By just observing our sample, two variables appear to be somewhat biasedly represented. Firstly, Tashkent city residents present a slight majority (53.1%) of the sample. However, this is not surprising and should not be considered an overrepresentation since it is considered both the administrative and business capital of the country, with a much larger economically active population, most of whom come from other regions of the country. Secondly, females represent a relatively small portion (15.3%) of the sample despite our efforts to encourage active participation of both genders in the survey. Again, this should also not be considered a significant misrepresentation because female labor force participation is 29% lower compared to males in Uzbekistan (World Bank Group 2024b). Furthermore, in a typical Uzbek family, males are considered the head of the household and are generally responsible for investment decisions. Both of these factors may explain the low representation of females in the sample. |

References

- Abdullayev, Azamat, Juliana Juliana, and Gulnora Bekimbetova. 2023. Investigating the Feasibility of Islamic Finance in Uzbekistan. Review of Islamic Economics and Finance 6: 63–74. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad, Wahida, and Rafisah Mat Radzi. 2011. Sustainability of Sukuk and Conventional Bond during Financial Crisis: Malaysia’s Capital Market. Global Economy and Finance Journal 4: 33–45. [Google Scholar]

- Ananth, Cande, and David G. Kleinbaum. 1997. Regression Models for Ordinal Responses: A Review of Methods and Applications. International Journal of Epidemiology 26: 1323–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asadov, Alam, and Bahodir Nurmukhamedov. 2023. Development of Islamic Finance in CIS Countries: In the Example of Uzbekistan, 1st ed. Riyadh: Obeikan Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Asadov, Alam, and Ikhtiyorjon Turaboev. 2023. Legal Challenges Hindering the Development of Islamic Finance in Uzbekistan. Access to Justice in Eastern Europe 6: 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asadov, Alam, Ikhtiyorjon Turaboev, and Mohd Zakhiri Md. Nor. 2023. Legal Challenges in Establishing the Islamic Capital Market in Uzbekistan. ISRA International Journal of Islamic Finance 15: 45–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asadov, Alam, Ikhtiyorjon Turaboev, and Ramazan Yildirim. 2024. Prospects of Islamic Capital Market in Uzbekistan: Issues and Challenges. International Journal of Islamic and Middle Eastern Finance and Management 17: 102–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asian Development Bank. 2024. Economic Forecasts for Uzbekistan. Asian Development Outlook (ADO). April. Available online: https://www.adb.org/where-we-work/uzbekistan/economy (accessed on 28 July 2024).

- Associated Press of Pakistan. 2024. Uzbekistan Possess Huge Potential to Become Financial Hub for Central Asia. Business. May 3. Available online: https://www.app.com.pk/business/uzbekistan-possess-huge-potential-to-become-financial-hub-for-central-asia/#google_vignette (accessed on 28 July 2024).

- Bacha, Obiyathulla Ismath, and Abbas Mirakhor. 2013. Islamic Capital Markets and Development. In Economic Development and Islamic Finance. Edited by Zamir Iqbal and Abbas Mirakhor. Washington, DC: The World Bank, pp. 253–74. [Google Scholar]

- Botirova, Hulkar Olimjonovna. 2023. Overview of Islamic Finance in Uzbekistan: Challenges and Prospects. European Journal of Economics, Finance and Business Development 1: 20–25. [Google Scholar]

- Boujlil, Rhada, M. Kabir Hassan, and Rihab Grassa. 2020. Sovereign Debt Issuance Choice: Sukuk vs. Conventional Bonds. Journal of Islamic Monetary Economics and Finance 6: 275–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, Gil, and Andrey Kudryavtsev. 2012. Investor Rationality and Financial Decisions. Journal of Behavioral Finance 13: 11–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danila, Nevi, Noor Azlina Azizan, and Umara Noreen. 2023. A Comparative Study between Retail Sukuk and Retail Bonds in Indonesia. International Journal of Business and Globalisation 33: 373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daryo. 2021. Ўзбeкиcтoндa Иcлoмий Moлиялaштиpиш Heгa Tўлиқ Aмaлгa Oшиpилмaгaнигa Изoҳ Бepилди (It Was Explained Why Islamic Financing Was Not Fully Implemented in Uzbekistan). Www.Daryo.Uz. September 2. Available online: https://daryo.uz/k/2021/09/02/ozbekistonda-islomiy-moliyalashtirish-nega-toliq-amalga-oshirilmaganiga-izoh-berildi/ (accessed on 3 August 2024).

- Echchabi, Abdelghani, Hassanuddeen Abd Aziz, and Umar Idriss. 2016. Does Sukuk Financing Promote Economic Growth: An Emphasis on the Major Issuing Countries. Turkish Journal of Islamic Economics 3: 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Echchabi, Abdelghani, Hassanuddeen Abd Aziz, and Umar Idriss. 2018. The Impact of Sukuk Financing on Economic Growth: The Case of GCC Countries. International Journal of Financial Services Management 9: 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, Shafiqul, Mohsin Dhali, Saghir Munir Mehar, and Fazluz Zaman. 2022. Islamic Securitization as a Yardstick for Investment in Islamic Capital Markets. International Journal of Service Science, Management, Engineering, and Technology 13: 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ICD, and LSEG. 2023. Islamic Finance Development Report 2023: Navigating Uncertainty. London: LSEG. [Google Scholar]

- Imamnazarov, Jakhongir. 2020. Landscaping Analysis of Islamic Finance Instruments in Uzbekistan. Tashkent, Uzbekistan. Available online: https://www.undp.org/sites/g/files/zskgke326/files/migration/uz/ENG_Landscaping-IF-in-Uzbekistan_final.pdf (accessed on 3 August 2024).

- Indriani, Mirna, Ratna Mulyany, and N. A. Indayani. 2020. Behaviour towards Investments in Islamic Capital Market: An Exploratory Study. International Journal of Trade and Global Markets 13: 454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islamic Corporation for the Development of the Private Sector (ICD). 2021. ICD Signs Line of Finance Agreements with Four Uzbekistan Banks. ICD News. September 4. Available online: https://icd-ps.org/en/news/icd-signs-line-of-finance-agreements-with-four-uzbekistan-banks (accessed on 30 July 2024).

- Islamic Finance News (IFN). 2023. Intercascade Group’s Sukuk: First in Kyrgyzstan. Available online: https://www.islamicfinancenews.com/intercascade-groups-sukuk-first-in-kyrgyzstan.html (accessed on 14 May 2024).

- Jivraj, Hassan. 2024. Challenges Impede Islamic Finance Growth in Central Asia. Salaam Gateway. April 24. Available online: https://salaamgateway.com/story/challenges-impede-islamic-finance-growth-in-central-asia (accessed on 30 July 2024).

- Kahneman, Daniel, and Amos Tversky. 2013. Prospect Theory: An Analysis of Decision Under Risk. In Handbook of the Fundamentals of Financial Decision Making: Part I. Singapore: World Scientific, pp. 99–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaki, G N, and Bilal Ahmad Malik. 2014. Islamic Banking and Finance in Post—Soviet Central Asia with Special Reference to Kazakhstan. International Journal of Excellence in Islamic Banking and Finance 4: 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khasanov, Khusan. 2019. Prospects for the Development of Islamic Finance in the Republic of Uzbekistan. In Round Table Meeting on Prospects of Development of Islamic Finance in Uzbekistan. Tashkent: Center for Development Strategy, Uzbekistan. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/339552084_Prospects_for_the_Development_of_Islamic_Finance_in_the_Republic_of_Uzbekistan (accessed on 23 June 2024).

- Khusanov, Murod. 2022. Uzbekistan Opens for Islamic Finance. Islamic Finance News (IFN). December 16. Available online: https://www.islamicfinancenews.com/uzbekistan-opens-for-islamic-finance.html (accessed on 31 March 2024).

- Krische, Susan D. 2019. Investment Experience, Financial Literacy, and Investment-Related Judgments. Contemporary Accounting Research 36: 1634–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kun.uz. 2021. Ministerial Official Explains Why Islamic Finance Is Not Fully Introduced in Uzbekistan. Kun.Uz. September 3. Available online: https://kun.uz/en/news/2021/09/03/ministerial-official-explains-why-islamic-finance-is-not-fully-introduced-in-uzbekistan (accessed on 13 May 2023).

- Laldin, Mohamad Akram. 2008. Islamic Financial System: The Malaysian Experience and the Way Forward. Humanomics 24: 217–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ledhem, Mohammed Ayoub. 2022. Does Sukuk Financing Boost Economic Growth? Empirical Evidence from Southeast Asia. PSU Research Review 6: 141–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, J. Scott, and Jeremy Freese. 2014. Regression Models for Categorical Dependent Variables Using Stata, 3rd ed. College Station: Stata Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mallick, Debdulal. 2009. Marginal and Interaction Effects in Ordered Response Models. Munich: MPRA Paper, p. 1332. [Google Scholar]

- Nagimova, Almira. 2021. Islamic Finance in the CIS Countries. Campbell: Academus Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nizomiddinov, Muzaffar. 2020. Uzbekistan Can Become a CIS Leader in Islamic Finance. Kun.Uz. August 4. Available online: https://kun.uz/en/94663863#! (accessed on 28 July 2024).

- Nusrathujaev, Hondamir. 2020. Opportunities and Expectations for Islamic Finance in Uzbekistan (Country Report: Uzbekistan). Islamic Finance News, December. 131. [Google Scholar]

- Peduzzi, Peter, John Concato, Elizabeth Kemper, Theodore R. Holford, and Alvan R. Feinstein. 1996. A Simulation Study of the Number of Events per Variable in Logistic Regression Analysis. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 49: 1373–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pew Research Center. 2009. Mapping the Global Muslim Population: A Report on the Size and Distribution of the World’s Muslim Population. Washington, D.C. Available online: https://microdata.worldbank.org/index.php/citations/3606 (accessed on 17 May 2024).

- Sachan, Abhishek, and Pawan Kumar Chugan. 2020. Availability Bias of Urban and Rural Investors: Relationship Study of the Gujarat State of India. Journal of Behavioural Economics, Finance, Entrepreneurship, Accounting and Transport 8: 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Salman, Muhammad, Bakhtiar Khan, Sher Zaman Khan, and Rafi Ullah Khan. 2021. The Impact of Heuristic Availability Bias on Investment Decision-making: Moderated Mediation Model. Business Strategy & Development 4: 246–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, Ravindra, and Naurang Singh Mangat. 1996. Stratified Sampling. In Elements of Survey Sampling. Edited by Ravindra Singh and Naurang Singh Mangat. Cham: Springer-Science+Business Media, B.V., pp. 102–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivaramakrishnan, Sreeram, Mala Srivastava, and Anupam Rastogi. 2017. Attitudinal Factors, Financial Literacy, and Stock Market Participation. International Journal of Bank Marketing 35: 818–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smaoui, Houcem, and Mohsin Khawaja. 2017. The Determinants of Sukuk Market Development. Emerging Markets Finance and Trade 53: 1501–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statistical Agency of Uzbekistan. 2024. The Permanent Population in Uzbekistan Increases Daily by an Average of 1.8 Thousand People. Agency News. April 16. Available online: https://stat.uz/en/press-center/news-of-committee/52809-o-zbekisto-nda-doimiy-ah-oli-soni-har-kuni-o-rtacha-1-8-ming-kishiga-oshmoqda-5 (accessed on 17 May 2024).

- The Tashkent Times. 2024. Average Uzbekistan before Tax Salary at US$ 370. The Tashkent Times. January 30. Available online: https://tashkenttimes.uz/national/12411-average-uzbekistan-before-tax-salary-at-us-370 (accessed on 31 July 2024).

- Van Rooij, Maarten, Annamaria Lusardi, and Rob Alessie. 2011. Financial Literacy and Stock Market Participation. Journal of Financial Economics 101: 449–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank Group. 2024a. Uzbekistan: Overview. Uzbekistan Overview. Available online: https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/uzbekistan/overview#context (accessed on 28 July 2024).

- World Bank Group. 2024b. World Bank Country Gender Assessment Report: Uzbekistan. Country Gender Assessment Report. Available online: https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/uzbekistan/publication/country-gender-assessment-2024 (accessed on 31 July 2024).

- Worldometer. 2023. Uzbekistan Demographics 2023 (Population, Age, Sex, Trends). Uzbekistan Demographics 2023. Available online: https://www.worldometers.info/demographics/uzbekistan-demographics/ (accessed on 31 July 2024).

- Worldometer. 2024. Central Asia Population (LIVE). Available online: https://www.worldometers.info/world-population/central-asia-population/ (accessed on 17 May 2024).

- Yusfiarto, Rizaldi, Septy Setia Nugraha, Lu’liyatul Mutmainah, Izra Berakon, Sunarsih Sunarsih, and Achmad Nurdany. 2023. Examining Islamic Capital Market Adoption from a Socio-Psychological Perspective and Islamic Financial Literacy. Journal of Islamic Accounting and Business Research 14: 574–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Dependent Variables | Intent to Buy sukuk if Offered in Uzbekistan | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Names | Categories | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | Total |

| Gender (femdum) | Female (1) | 1.02 | 8.67 | 2.55 | 3.06 | 15.31 |

| Male (0) | 4.08 | 31.63 | 33.67 | 15.31 | 84.69 | |

| Married (mardum) | Married (1) | 3.57 | 28.06 | 26.02 | 11.73 | 69.39 |

| Single (0) | 1.53 | 11.73 | 9.69 | 5.61 | 28.57 | |

| Divorced (0) | 0 | 0 | 0.51 | 0.51 | 1.02 | |

| Widowed (0) | 0 | 0.51 | 0 | 0.51 | 1.02 | |

| Tashkent city resident (tashdum) | Yes (1) | 3.57 | 23.98 | 18.88 | 6.63 | 53.06 |

| No (0) | 1.53 | 16.33 | 17.35 | 11.73 | 46.94 | |

| Education industry (edudum) | Yes (1) | 3.06 | 15.31 | 15.82 | 5.61 | 39.8 |

| No (0) | 2.04 | 25 | 20.41 | 12.76 | 60.2 | |

| Financial industry (findum) | Yes (1) | 0 | 7.14 | 6.12 | 3.57 | 16.84 |

| No (0) | 5.1 | 33.16 | 30.1 | 14.8 | 83.16 | |

| Grant total | Percentage | 5.1 | 40.31 | 36.22 | 18.37 | 100 |

| Count | 10 | 79 | 71 | 36 | 196 | |

| Variable | Mean | Median | SD. | Min | Max | Skew. | Kurt. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| buysuk | 2.679 | 3 | 0.831 | 1 | 4 | 0.120 | 2.231 |

| age | 32.888 | 35 | 8.06 | 18 | 55 | 0.517 | 2.623 |

| income | 12.801 | 7.5 | 11.862 | 1 | 40 | 1.161 | 3.341 |

| cmknow | 2.776 | 3 | 1.100 | 1 | 5 | 0.059 | 2.305 |

| invexpr | 2.515 | 2 | 1.025 | 1 | 5 | 0.188 | 2.312 |

| sukknow | 2.163 | 2 | 1.213 | 1 | 5 | 0.705 | 2.350 |

| ismstkknow | 1.985 | 2 | 1.000 | 1 | 5 | 0.679 | 2.469 |

| stkshrcomp | 4.622 | 5 | 0.848 | 1 | 5 | −2.743 | 10.648 |

| buysuk | Age | Income | cmknow | invexpr | sukknow | ismstkknow | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| age | −0.0880 | ||||||

| (0.2202) | |||||||

| income | 0.0192 | 0.3988 * | |||||

| (0.7891) | (0.0000) | ||||||

| cmknow | 0.1562 * | 0.1900 * | 0.2411 * | ||||

| (0.0288) | (0.0076) | (0.0007) | |||||

| invexpr | 0.2254 * | 0.0479 | 0.2398 * | 0.5440 * | |||

| (0.0015) | (0.5046) | (0.0007) | (0.0000) | ||||

| sukknow | 0.3219 * | 0.0553 | 0.1262 | 0.4580 * | 0.3692 * | ||

| (0.0000) | (0.4411) | (0.0781) | (0.0000) | (0.0000) | |||

| ismstkknow | 0.3149 * | 0.0455 | 0.1249 | 0.4816 * | 0.4330 * | 0.7887 * | |

| (0.0000) | (0.5261) | (0.0811) | (0.0000) | (0.0000) | (0.0000) | ||

| stkshrcomp | 0.2272 * | −0.1847 * | −0.0884 | −0.1078 | −0.1350 | 0.0653 | −0.0190 |

| (0.0014) | (0.0096) | (0.2181) | (0.1324) | (0.0593) | (0.3634) | (0.7920) |

| Model | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Coef. | Odds Ratio | p-Value | Coef. | Odds Ratio | p-Value | Coef. | Odds Ratio | p-Value | |

| age | 0.010 | 1.010 | 0.743 | |||||||

| 1.femdum | −0.518 | 0.596 | 0.360 | −0.511 | 0.600 | 0.274 | ||||

| 1.mardum | −0.085 | 0.919 | 0.832 | |||||||

| 1.tashdum | −0.767 ** | 0.464 | 0.019 | −0.683 ** | 0.505 | 0.017 | −0.758 *** | 0.469 | 0.008 | |

| 1.edudum | 0.140 | 1.150 | 0.695 | |||||||

| 1.findum | −0.420 | 0.657 | 0.367 | −0.374 | 0.688 | 0.313 | ||||

| income | −0.001 | 0.999 | 0.955 | |||||||

| cmknow | 2 | −0.515 | 0.597 | 0.444 | ||||||

| 3 | −0.364 | 0.695 | 0.618 | |||||||

| 4 | 0.026 | 1.026 | 0.973 | |||||||

| 5 | −0.536 | 0.585 | 0.641 | |||||||

| invexpr | 2 | 1.049 ** | 2.854 | 0.048 | 0.907 * | 2.476 | 0.070 | 0.897 * | 2.453 | 0.074 |

| 3 | 0.706 | 2.026 | 0.164 | 0.698 | 2.010 | 0.158 | 0.706 | 2.026 | 0.154 | |

| 4 | 1.421 ** | 4.143 | 0.017 | 1.468 ** | 4.342 | 0.010 | 1.399 ** | 4.052 | 0.014 | |

| 5 | 2.875 *** | 17.723 | 0.006 | 3.124 *** | 22.748 | 0.000 | 3.245 *** | 25.666 | 0.000 | |

| sukknow | 2 | 0.331 | 1.392 | 0.426 | 0.405 | 1.499 | 0.277 | 0.435 | 1.545 | 0.242 |

| 3 | 1.323 ** | 3.753 | 0.016 | 1.486 *** | 4.421 | 0.000 | 1.459 *** | 4.302 | 0.001 | |

| 4 | 0.545 | 1.725 | 0.412 | 0.975 ** | 2.650 | 0.032 | 0.937 ** | 2.553 | 0.033 | |

| 5 | 2.384 ** | 10.849 | 0.050 | 2.950 *** | 19.108 | 0.003 | 2.793 *** | 16.338 | 0.004 | |

| ismstkknow | 2 | 0.203 | 1.225 | 0.616 | ||||||

| 3 | 0.329 | 1.390 | 0.544 | |||||||

| 4 | 0.715 | 2.044 | 0.334 | |||||||

| 5 | 12.349 *** | 230,785.2 | 0.000 | |||||||

| stkshrcomp | 2 | 4.267 *** | 71.318 | 0.003 | 4.221 ** | 68.101 | 0.011 | 4.096 ** | 60.073 | 0.017 |

| 3 | 4.359 *** | 78.210 | 0.000 | 4.378 *** | 79.652 | 0.000 | 4.111 *** | 60.996 | 0.000 | |

| 4 | 3.717 *** | 41.124 | 0.000 | 3.861 *** | 47.529 | 0.000 | 3.663 *** | 38.976 | 0.000 | |

| 5 | 4.478 *** | 88.091 | 0.000 | 4.480 *** | 88.216 | 0.000 | 4.326 *** | 75.641 | 0.000 | |

| Cutpoints | Coef. | [95% Conf. | Interval] | Coef. | [95% Conf. | Interval] | Coef. | [95% Conf. | Interval] | |

| /cut1 | 1.577 | −1.485 | 4.639 | 1.551 | −0.430 | 3.532 | 1.507 | −0.473 | 3.486 | |

| /cut2 | 5.072 | 1.824 | 8.320 | 5.017 | 2.902 | 7.132 | 4.933 | 2.827 | 7.040 | |

| /cut3 | 7.152 | 3.791 | 10.514 | 7.066 | 4.839 | 9.294 | 6.969 | 4.758 | 9.181 | |

| Statistics | Statistic values | |||||||||

| Pseudo-R2 | 0.147 | 0.139 | 0.135 | |||||||

| Log-likelihood | −200.07 | −201.96 | −203.05 | |||||||

| Wald χ2 | 280.78 | 62.58 | 60.08 | |||||||

| p-value (χ2) | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | |||||||

| BIC | 558.48 | 498.93 | 490.55 | |||||||

| No. of obs. | 196 | 196 | 196 | |||||||

| Variables | Coef. | Odds Ratio | z Stat | p-Value | % | %StdX | SDofX |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.tashdum | −0.758 *** | 0.469 | −2.650 | 0.008 | −53.1 | −31.5 | 0.500 |

| invexpr 2 | 0.897 * | 2.453 | 1.790 | 0.074 | 145.3 | 52.5 | 0.470 |

| 3 | 0.706 | 2.026 | 1.430 | 0.154 | 102.6 | 39.0 | 0.466 |

| 4 | 1.399 ** | 4.052 | 2.440 | 0.014 | 305.2 | 66.8 | 0.366 |

| 5 | 3.245 *** | 25.666 | 3.920 | 0.000 | 2466.6 | 58.4 | 0.142 |

| sukknow 2 | 0.435 | 1.545 | 1.170 | 0.242 | 54.5 | 20.8 | 0.434 |

| 3 | 1.459 *** | 4.302 | 3.430 | 0.001 | 330.2 | 72.9 | 0.375 |

| 4 | 0.937 ** | 2.553 | 2.130 | 0.033 | 155.3 | 38.2 | 0.346 |

| 5 | 2.793 *** | 16.338 | 2.890 | 0.004 | 1533.8 | 74.0 | 0.198 |

| stkshrcomp 2 | 4.096 ** | 60.073 | 2.380 | 0.017 | 5907.3 | 65.5 | 0.123 |

| 3 | 4.111 *** | 60.996 | 3.760 | 0.000 | 5999.6 | 126.0 | 0.198 |

| 4 | 3.663 *** | 38.976 | 3.860 | 0.000 | 3797.6 | 268.4 | 0.356 |

| 5 | 4.326 *** | 75.641 | 4.320 | 0.000 | 7464.1 | 519.7 | 0.422 |

| Cut points | Coef. | Std. Err. | [95% Conf. | Interval] | |||

| /cut1 | 1.507 | 1.010 | −0.473 | 3.486 | Sensitivity | 0.407 | 2.607 |

| /cut2 | 4.933 | 1.075 | 2.827 | 7.040 | analysis | 3.858 | 6.008 |

| /cut3 | 6.969 | 1.128 | 4.758 | 9.181 | 5.841 | 8.097 | |

| Statistics | |||||||

| Pseudo-R2 | 0.135 | ||||||

| Log-likelihood | −203.05 | ||||||

| Wald χ2 | 60.08 | ||||||

| p-value (χ2) | 0.000 | ||||||

| No. of obs. | 196 | ||||||

| Variables | Chi2 | p-Value | df |

|---|---|---|---|

| All | 7 | 0.509 | 8 |

| tashdum | 0.250 | 0.884 | 2 |

| invexpr | 0.440 | 0.804 | 2 |

| sukknow | 5.170 | 0.075 | 2 |

| stkshrcomp | 0.040 | 0.982 | 2 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Asadov, A. Empirical Analysis of Demand for Sukuk in Uzbekistan. Economies 2024, 12, 220. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies12080220

Asadov A. Empirical Analysis of Demand for Sukuk in Uzbekistan. Economies. 2024; 12(8):220. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies12080220

Chicago/Turabian StyleAsadov, Alam. 2024. "Empirical Analysis of Demand for Sukuk in Uzbekistan" Economies 12, no. 8: 220. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies12080220

APA StyleAsadov, A. (2024). Empirical Analysis of Demand for Sukuk in Uzbekistan. Economies, 12(8), 220. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies12080220