Econometric Analysis of South Africa’s Fiscal and Monetary Policy Effects on Economic Growth from 1980 to 2022

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Existing Theoretical Economic Framework

2.2. Previous Empirical Studies Relevant to This Study

2.2.1. Effects of Associated Fiscal Policy Variables on Economic Growth

| Author(s) | Country/Region | Key Findings of the Study |

|---|---|---|

| Arestis et al. (2021) | Turkey | The study supports the Keynesian view, based on economically significant government expenditures, rather than Wagner’s law. Empirical findings indicated that government expenditures on defence, economic affairs, education, health, housing and community amenities, and social protection positively affect output through Keynesian fiscal multiplier and investment-accelerator mechanisms. |

| Iwegbunam and Robinson (2018) | South Africa | The Keynesian theory was confirmed, while Wagner’s theory was rejected. |

| Mlilo and Netshikulwe (2017) | South Africa | Discovered supporting evidence for the Keynesian theory, but no evidence was found for Wagner’s law. |

| Permana and Wika (2014) | Indonesia | Confirmed the validity of Wagner’s theory. |

| Sedrakyan and Varela-Candamio (2019) | Armenia and Spain | Accepted Keynesian theory for short-term economic conditions and Wagner’s law for long-term economic trends. |

| Author(s) | Country/Region | Key Findings of the Study |

|---|---|---|

| Ayana et al. (2023) | Sub-Saharan Africa | The initial impact of government revenue on growth is negative, but growth is subsequently enhanced through interaction with institutional integrity. |

| Moyo et al. (2021) | South Africa | There is a significant and direct correlation between tax revenue and economic growth. |

| Nguyen and Darsono (2022) | Asian countries | Inadequate governance resulted in a decline in government revenue. |

| Roşoiu (2015) | Romania | The government revenue has a positive impact on the gross domestic product (GDP). |

| Author(s) | Country/Region | Key Findings of the Study |

|---|---|---|

| Hassan et al. (2023) | Kenya | External debt has a small positive impact, while domestic debt has a small negative impact. |

| Kithinji (2020) | Kenya | The composition of public debt and government spending has a substantial impact on economic growth. |

| Mothibi and Mncayi-Makhanya (2019) | South Africa | Negative relationship between government debt and economic growth. |

| Saungweme and Odhiambo (2020) | South Africa | Foreign debt exerts a detrimental influence on the economy over an extended period, while domestic debt yields favourable effects in the short term. |

2.2.2. Effects of Associated Monetary Policy Variables on Economic Growth

| Author(s) | Country/Region | Key Findings of the Study |

|---|---|---|

| Anochiwa and Maduka (2015) | Nigeria | Long-term relationship between inflation and economic growth; thus, recommended inflation rate below 10%. |

| Bittencourt et al. (2015) | SADC member states | Economies were negatively impacted by the increasing inflation rates. |

| Khoza et al. (2016) | South Africa | Optimal economic growth can be achieved by maintaining a recommended inflation rate of 5.3%. |

| Mbulawa (2015) | Botswana | An inflation rate of 3–6% is suggested as a means to promote economic growth. |

| Author(s) | Country/Region | Key Findings of the Study |

|---|---|---|

| Ashour and Yong (2018) | Developing countries | A fixed exchange regime is associated with a higher rate of economic growth. |

| Ehikioya (2019) | Nigeria | Continual fluctuations in exchange rates have a detrimental effect on the growth of the economy. |

| Muzekenyi et al. (2019) | South Africa | Real exchange rates have a detrimental effect on economic growth in both the short and long term. |

| Patel and Mah (2018) | South Africa | There is a strong negative correlation between real exchange rates and economic growth. |

| Author(s) | Country/Region | Key Findings of the Study |

|---|---|---|

| Matemilola et al. (2015) | South Africa | There is a significant negative correlation between interest rates and long-term economic growth. |

| Nyasha and Odhiambo (2015) | South Africa | Interest rate reforms have a positive impact on economic growth in both the short and long term. |

| Sari et al. (2022) | Indonesia | Interest rates exert a negative impact on economic growth. |

| Shaukat et al. (2019) | Transitional economies | Suggested lowering interest rates as a means to stimulate economic growth. |

| Author(s) | Country/Region | Key Findings of the Study |

|---|---|---|

| Buthelezi (2023) | South Africa | In high economic scenarios, an increase in the money supply results in a decrease in GDP. |

| Chaitip et al. (2015) | ASEAN Economic Community | Long-term relationship between money supply and economic growth. |

| Dingela and Khobai (2017) | South Africa | There is a robust and direct positive relationship between the amount of money in circulation and the rate of economic growth. |

| Matres and Le (2021) | 217 countries | Initially, a negative correlation between the growth of the money supply and economic growth. However, this relationship changes to a positive correlation in a subsequent year. |

2.3. Other Viewpoints on Economic Growth and Governmental Policy Measures

2.3.1. The Relationship between Debt and Economic Growth

2.3.2. The Concept of Cumulative Causation and Its Impact on Economic Development

2.3.3. The Washington Consensus and Systematic Restructuring

2.3.4. Different Approaches to Development

3. Methodology

3.1. Data Preparation

3.2. Model Specification

| Variable | Description of the Variable | Measurement | Data Source * |

|---|---|---|---|

| lnGDP_growth_growth | Logarithm of gross domestic product growth rate | (% annual growth rate) | WB |

| lnGE | Logarithm of government expenditure | (% of GDP) | SARB |

| lnGR | Logarithm of government revenue | (% of GDP) | SARB |

| lnGD | Logarithm of government debt | (% of GDP) | SARB |

| lnIF | Logarithm of inflation (average consumer prices) | (% change) | WB |

| lnER | Logarithm of official exchange rate | (Ratio) | WB |

| lnMS | Logarithm of broad money supply (M3) | (% of GDP) | WB |

| lnIR | Logarithm of real interest rate | (%) | WB |

3.3. Empirical Estimation Technique

3.3.1. Unit Root Testing (ADF, PP, and KPSS)

3.3.2. ARDL Model as a Method of Cointegration

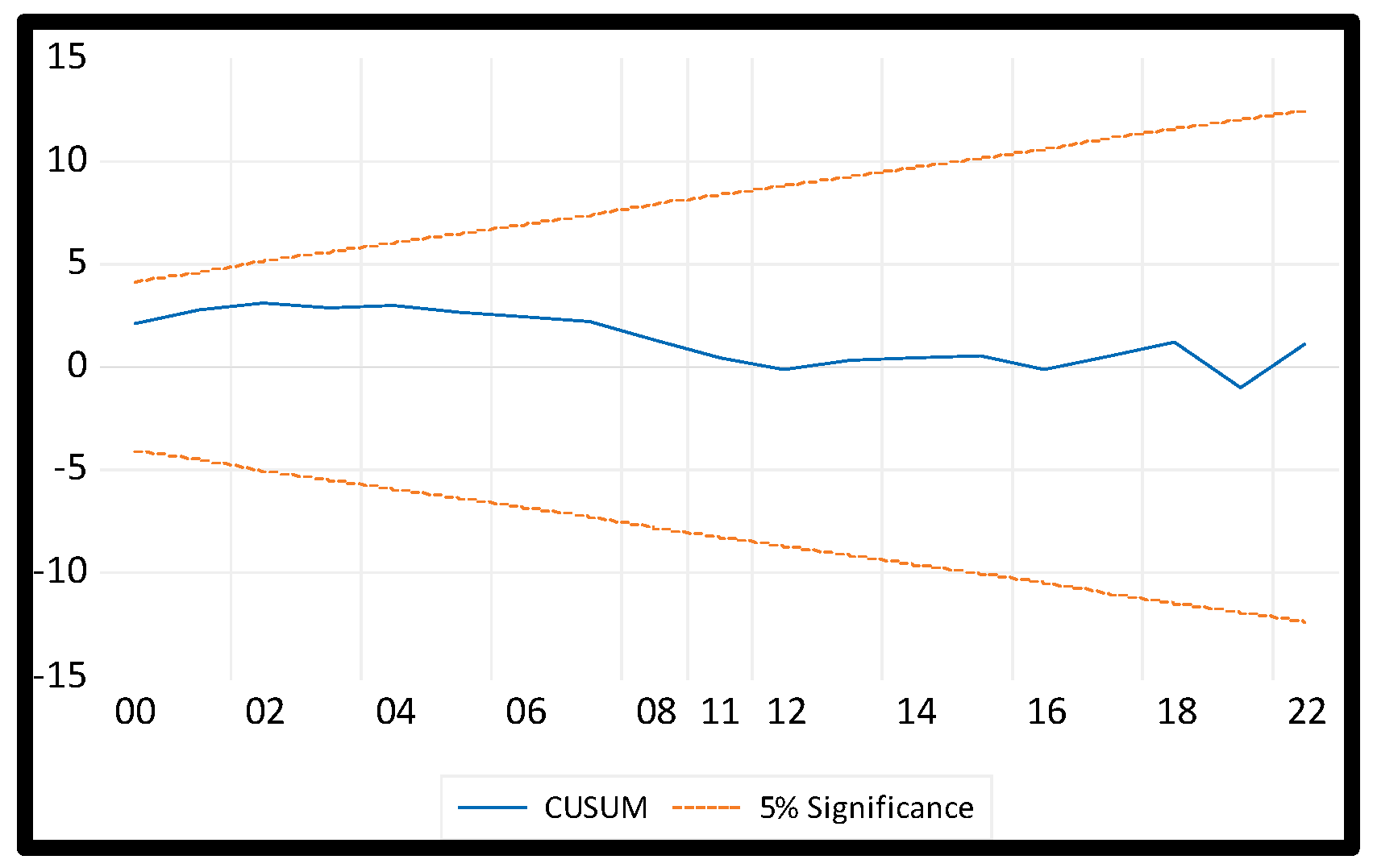

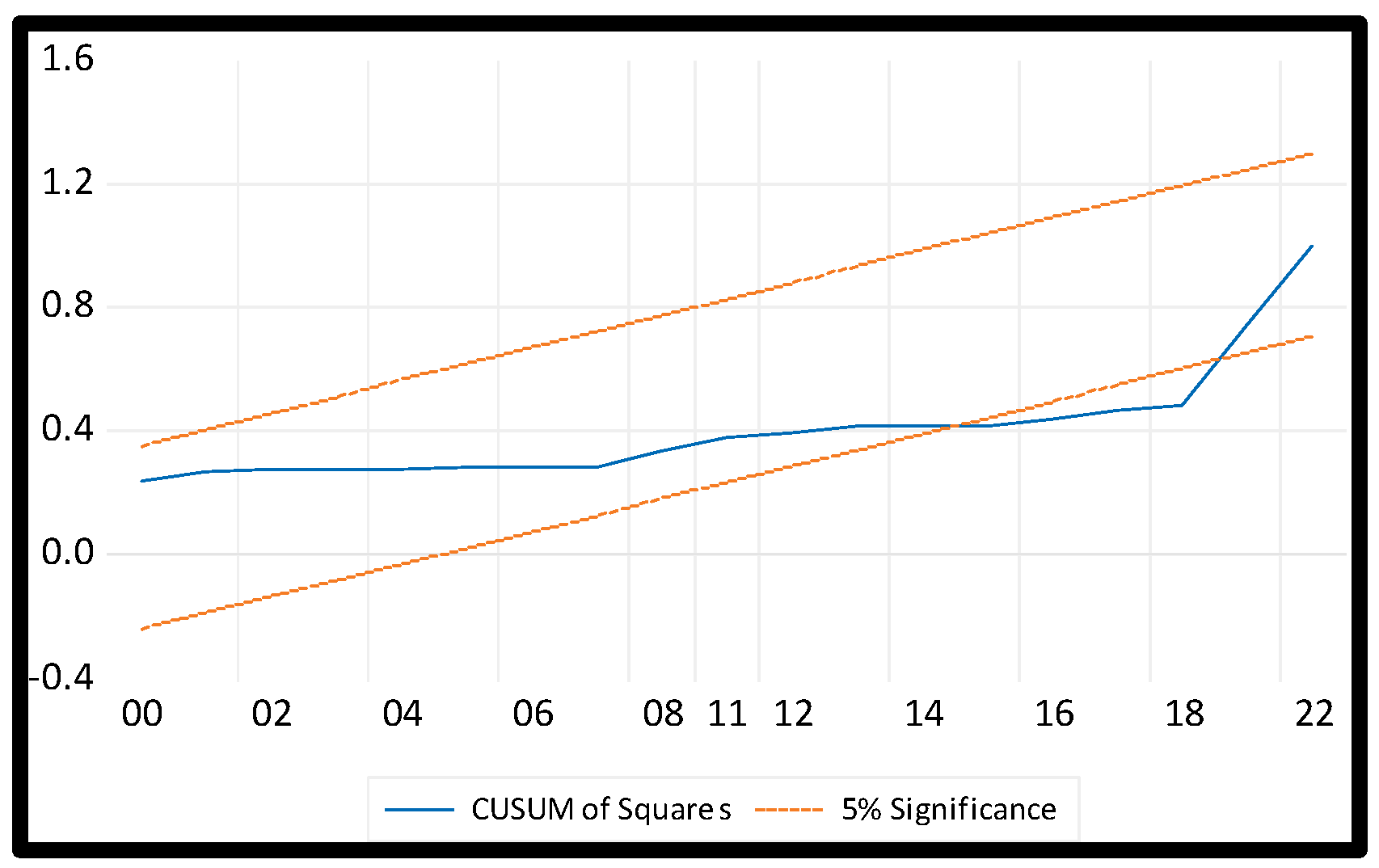

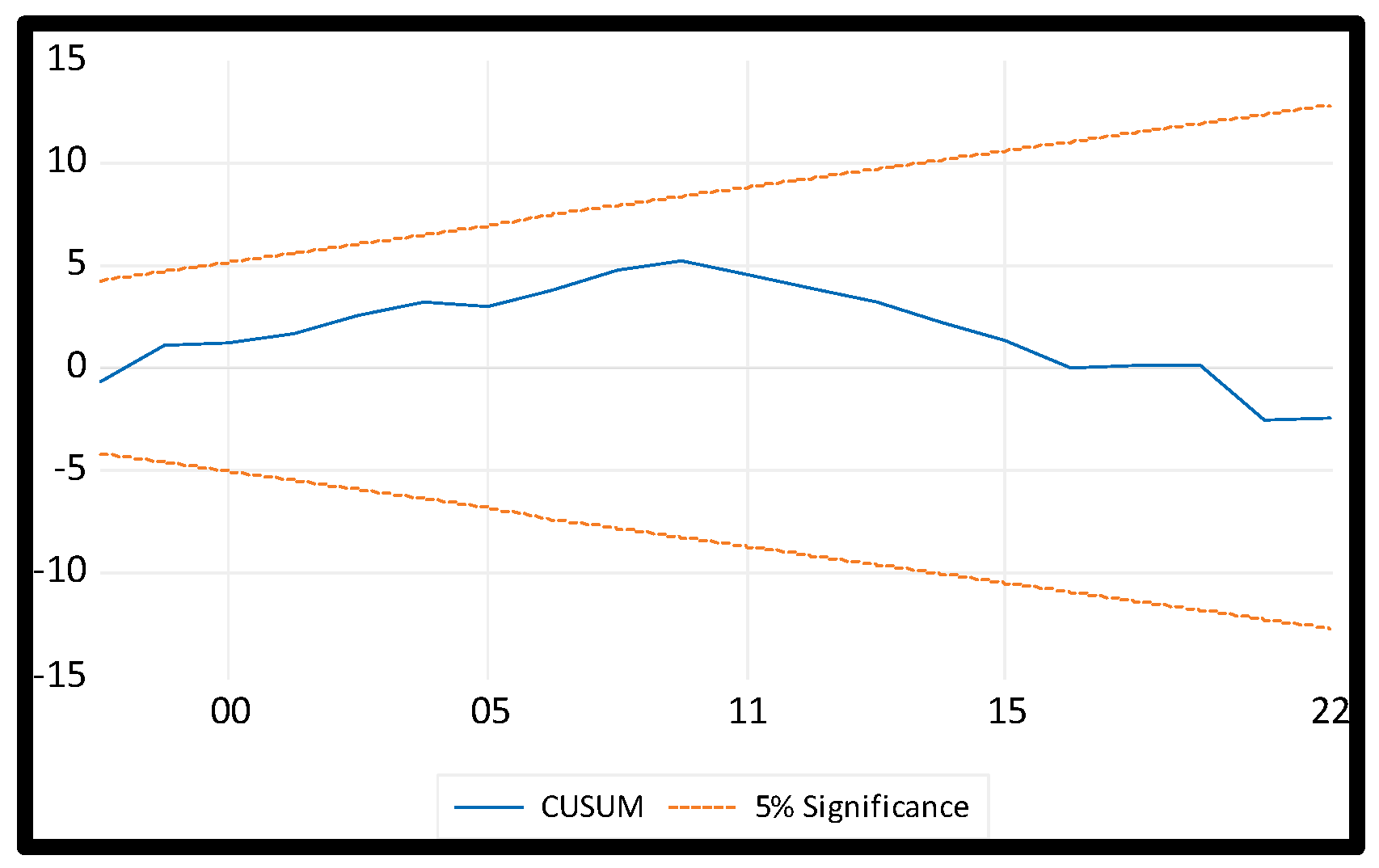

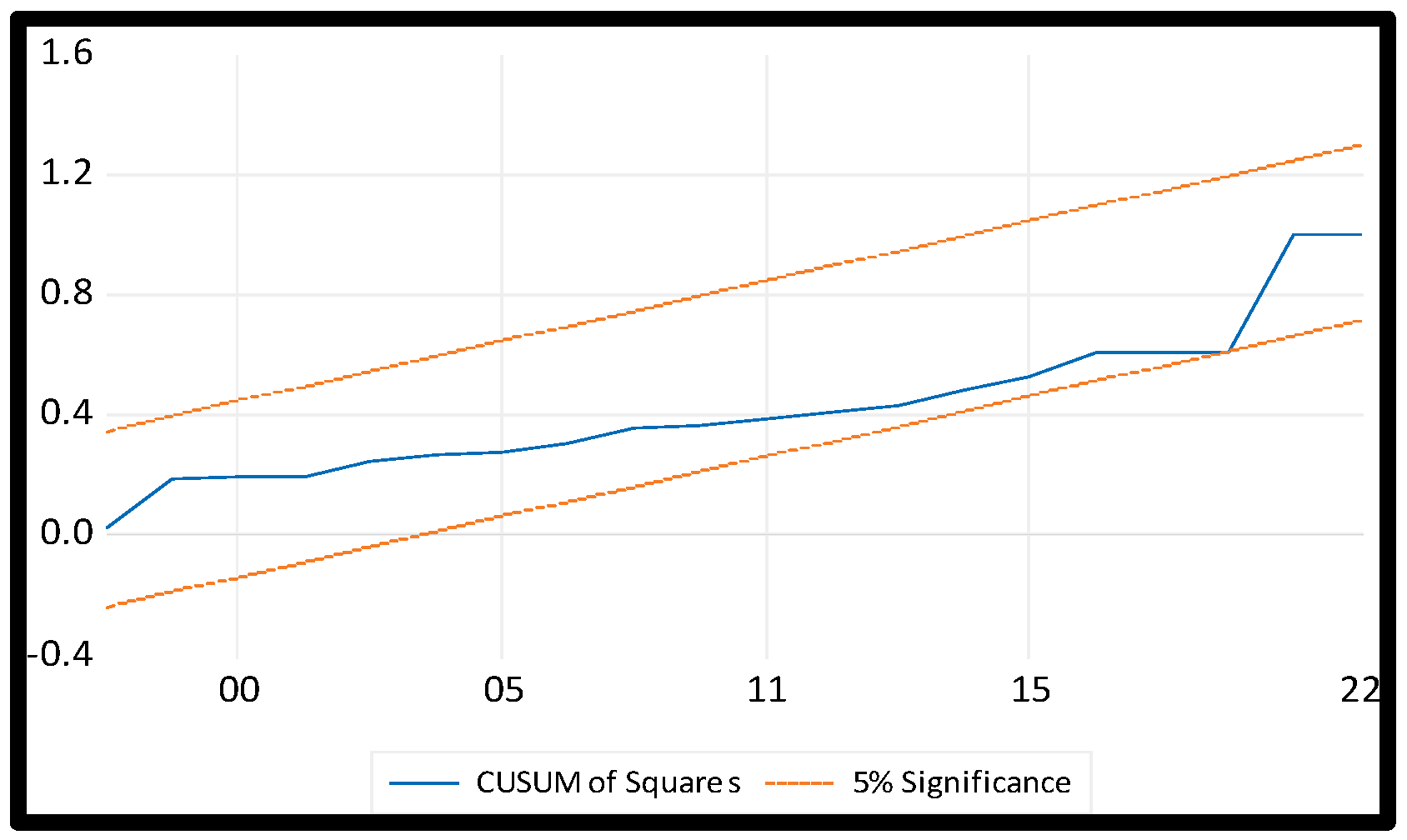

3.3.3. Diagnostic Testing of Fiscal and Monetary Policy Models

3.3.4. Pairwise Granger Causality Test of Fiscal and Monetary Policy Models

3.4. The Rationale behind Not Using Multivariate Analyses

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Statistical Description and Correlation Analysis

4.1.1. Descriptive Statistics

4.1.2. Correlation Analysis

4.2. Unit Root and Stationarity Tests

4.3. The Estimation of the ARDL Model

4.3.1. Empirical Analysis of Fiscal Policy Model

4.3.2. Empirical Analysis of Monetary Policy Model

5. Pairwise Granger Causality Test

5.1. Fiscal Policy Model Results

5.2. Monetary Policy Model Results

6. Conclusions and Policy Recommendations

- Evaluating the effectiveness of government expenditures and the impact of taxes on economic activity.

- Maintaining price stability and managing inflation, with minimal long-term impact on growth.

- Implementing macroeconomic policies and structural reforms to address infrastructure gaps and skill inconsistencies.

- Fostering private sector investment and growth through fiscal sustainability and effective debt management, even though the current study did not find evidence to suggest a direct link between government debt and economic growth.

7. Limitations and Suggestion for Future Research

Possible Implications due to Conflicting Results Observed

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Afzal, Muhammad, and Qaiser Abbas. 2009. Wagners Law in Pakistan: Another Look. Journal of Economics and International Finance 2: 12–19. [Google Scholar]

- Anochiwa, Lasbrey, and Anne Maduka. 2015. Inflation and Economic Growth in Nigeria: Empirical Evidence? Journal of Economics and Sustainable Development 6: 113–21. [Google Scholar]

- Arestis, Philip, Hüseyin Şen, and Ayşe Kaya. 2021. On the Linkage between Government Expenditure and output: Empirics of the Keynesian View versus Wagner’s Law. Economic Change and Restructuring 54: 265–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashour, Majidah, and Chen Chen Yong. 2018. The impact of exchange rate regimes on economic growth: Empirical study of a set of developing countries during the period 1974–2006. The Journal of International Trade & Economic Development 27: 74–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayana, Isubalew Daba, Wondaferahu Mulugeta Demissie, and Atnafu Gebremeskel Sore. 2023. Effect of government revenue on economic growth of sub-Saharan Africa: Does institutional quality matter? PLoS ONE 18: e0293847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Backhouse, Roger Edward. 2015. Samuelson, Keynes and the Search for a General Theory of Economics. Italian Economic Journal 1: 139–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Barro, Robert Joseph. 1989. The Ricardian Approach to Budget Deficits. Journal of Economic Perspectives 3: 37–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barro, Robert Joseph. 1990. Government Spending in a Simple Model of Endogeneous Growth. Journal of Political Economy 98: S103–S125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belongia, Micheal, and Peter Ireland. 2016. The Evolution of U.S. Monetary policy: 2000–2007. Journal of Economic Dynamics and Control 73: 78–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bender, Bruce. 1984. An Analysis of the Laffer Curve. Economic Inquiry 22: 414–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bittencourt, Manoel, Reneé van Eyden, and Monaheng Seleteng. 2015. Inflation and Economic Growth: Evidence from the Southern African Development Community. South African Journal of Economics 83: 411–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blinder, Alan Stuart. 1988. The Fall and Rise of Keynesian Economics. Economic Record 64: 278–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boianovsky, Mauro. 2004. The IS-LM Model and the Liquidity Trap Concept: From Hicks to Krugman. History of Political Economy 36: 92–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borner, Silvio. 1979. Who Has the Right Policy Perspective, the OECD or Its Monetarist Critics? Kyklos 32: 285–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breusch, Trevor Stanley. 1978. Testing for Autocorrelation in Dynamic Linear Models. Australian Economic Papers 17: 334–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buthelezi, Eugene Msizi. 2023. Impact of Money Supply in Different States of Inflation and Economic Growth in South Africa. Economies 11: 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaitip, Prasert, Kanchana Chokethaworn, Chukiat Chaiboonsri, and Monekeo Khounkhalax. 2015. Money Supply Influencing on Economic Growth-wide Phenomena of AEC Open Region. Procedia Economics and Finance 24: 108–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coger, Dalvan Moe. 2000. South Africa’s Future: From Crisis to Prosperity, and: Fault Lines: Journeys into the New South Africa, and: South Africa in Transition: The Misunderstood Miracle, and: A Concise History of South Africa, and: South Africa: A Narrative History (review). Africa Today 47: 182–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costanza, Robert. 1996. The Impact of Ecological Economics. Ecological Economics 19: 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crotty, James Robert. 1996. Is New Keynesian Investment Theory Really ‘Keynesian’? Reflections on Fazzari and Variato. Journal of Post Keynesian Economics 18: 333–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Ruomeng, Jun Li, and Dennis Zhang. 2019. Reducing Discrimination with Reviews in the Sharing Economy: Evidence from Field Experiments on Airbnb. Management Science 66: 1071–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daly, Herman Edward. 1991. Towards an Environmental Macroeconomics. Land Economics 67: 255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debrun, Xavier, and Radhicka Kapoor. 2010. Fiscal Policy and Macroeconomic Stability: Automatic Stabilizers Work, Always and Everywhere. IMF Working Papers 10: 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Ai, and Pierre Perron. 2008. A non-local perspective on the power properties of the CUSUM and CUSUM of squares tests for structural change. Journal of Econometrics 142: 212–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickey, David Alan, and Wayne Arthur Fuller. 1979. Distribution of the Estimators for Autoregressive Time Series with a Unit Root. Journal of the American Statistical Association 74: 427–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dingela, Siyasanga, and Hlalefang Khobai. 2017. Dynamic Impact of Money Supply on Economic Growth in South Africa. An ARDL Approach. Available online: https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/82539// (accessed on 20 July 2024).

- Dritsakis, Nikolaos. 2011. Demand for Money in Hungary: An ARDL Approach. Review of Economics & Finance 1: 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Du Plessis, Stan, Ben Smit, and Federico Sturzenegger. 2007. The Cyclicality Of Monetary And Fiscal Policy In South Africa Since 1994. The South African Journal of Economics 75: 391–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du Plessis, Stan, Ben Smit, and Rudi Steinbach. 2014. A Medium-Sized Open Economy DSGE Model of South Africa, South African Reserve Bank Working Paper Series, WP/14/04. Available online: https://www.resbank.co.za/content/dam/sarb/publications/working-papers/2014/6319/WP1404.pdf (accessed on 17 July 2024).

- Edoumiekumo, Samuel. 2010. Foreign direct investment and economic growth in Nigeria: A granger causality test. Journal of Research in National Development 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehikioya, Benjamin Ighodalo. 2019. The impact of exchange rate volatility on the Nigerian economic growth: An empirical investigation. Journal of Economics and Management 37: 45–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engle, Robert. 1982. Autoregressive Conditional Heteroscedasticity with Estimates of the Variance of United Kingdom Inflation. Econometrica 50: 987–1007. Available online: https://econpapers.repec.org/RePEc:ecm:emetrp:v:50:y:1982:i:4:p:987-1007 (accessed on 5 August 2019). [CrossRef]

- Friedman, Milton. 1953. Economic Advice and Political Limitations: Rejoinder. The Review of Economics and Statistics 35: 252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, Milton, and Anna Jacobson Schwartz. 1963. Money and Business Cycles. The Review of Economics and Statistics 45: 32–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godfrey, Leslie George. 1978. Testing for Higher Order Serial Correlation in Regression Equations when the Regressors Include Lagged Dependent Variables. Econometrica 46: 1303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gottesman, Aron, Lall Ramrattan, and Michael Szenberg. 2005. Samuelson’s economics: The continuing legacy. The Quarterly Journal of Austrian Economics 8: 95–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granger, Clive William John. 1969. Investigating Causal Relations by Econometric Models and Cross-spectral Methods. Econometrica 37: 424–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerdjikova, Ani. 2007. The New Institutional Economics of Markets. Journal of Institutional and Theoretical Economics 163: 517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gujarati, Damodar, and Dawn Cheree Porter. 2009. Basic Econometrics, 5th ed. New York: McGraw Hill Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Hassan, Mohamedamin Ahmed, Benedicto Onkoba Ongeri, and David Katuta Ndolo. 2023. The Effect of National Public Debt on Economic Growth in Kenya. European Scientific Journal 19: 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herzog, Lisa. 2014. Adam Smith on Markets and Justice. Philosophy Compass 9: 864–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hicks, John Richard. 1937. Mr. Keynes and the ‘Classics’; A Suggested Interpretation. Econometrica 5: 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, Rodolfo. 1987. Damodar Gujarati. Basic Econometrics. McGraw-Hill, 1978. Brazilian Review of Econometrics 7: 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooper, Vincent James. 2002. The Washington Consensus and Emerging Economies. SSRN Electronic Journal. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwegbunam, Ifeoma Anthonia, and Zurika Robinson. 2018. Revisiting Wagner’s Law in the South African Economy. Acta Universitatis Danubius. Œconomica 15: 16. Available online: http://journals.univ-danubius.ro/index.php/oeconomica/article/view/5294/5212 (accessed on 24 July 2024).

- Jarque, Carlos Manuel, and Anil Kumar Bera. 1987. A Test for Normality of Observations and Regression Residuals. International Statistical Review/Revue Internationale de Statistique 55: 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, Evan. 1983. Monetarism in Practice. The Australian Quarterly 55: 433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaldor, Nicholas. 1970. The Case for Regional Policies. Scottish Journal of Political Economy 27: 234–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keynes, John Maynard. 1936. The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money. Political Science Quarterly 51: 600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khobai, Hlalefang, and Pierre Le Roux. 2017. The Relationship between Energy Consumption, Economic Growth and Carbon Dioxide Emission: The Case of South Africa. International Journal of Energy Economics and Policy 7: 102–9. Available online: https://www.econjournals.com/index.php/ijeep/article/view/4361 (accessed on 12 June 2024).

- Khoza, Keorapetse, Relebogile Thebe, and Andrew Phiri. 2016. Nonlinear impact of inflation on economic growth in South Africa: A smooth transition regression analysis. International Journal of Sustainable Economy 8: 277–93. [Google Scholar]

- Kithinji, Angela Mucece. 2020. The Influence of Public Debt on Economic Growth in Kenyan Government. International Journal of Business Management and Economic Review 3: 120–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwiatkowski, Denis, Peter Charles Bonest Phillips, Peter Schmidt, and Yongcheol Shin. 1992. Testing the null hypothesis of stationarity against the alternative of a unit root. Journal of Econometrics 54: 159–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laidler, David. 1990. The Legacy of the Monetarist Controversy. Northampton: Edward Elgar Publishing, vol. 72, pp. 394–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucas, Robert Emerson. 1988. On the Mechanics of Economic Development. Journal of Monetary Economics 22: 3–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luks, Fred. 1998. The rhetorics of ecological economics. Ecological Economics 26: 139–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mago, Stephen. 2019. Urban Youth Unemployment in South Africa: Socio-Economic and Political Problems. Commonwealth Youth and Development 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marangos, John. 2008. The Evolution of the Anti-Washington Consensus Debate: From ‘Post-Washington Consensus’ to ‘After the Washington Consensus’. Competition & Change 12: 227–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, William. 2009. South Africa’s Subimperial Futures: Washington Consensus, Bandung Consensus, or Peoples’ Consensus? African Sociological Review / Revue Africaine De Sociologie 12: 122–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matemilola, Bolaji Tunde, Amin Noordin Bany-Ariffin, and Fatima Etudaiye Muhtar. 2015. The impact of monetary policy on bank lending rate in South Africa. Borsa Istanbul Review 15: 53–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matres, Javier de Oña García, and Tuan Viet Le. 2021. The Impact of Money Supply on the Economy: A Panel Study on Selected Countries. Journal of Economic Science Research 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mbulawa, Strike. 2015. Effect of Macroeconomic Variables on Economic Growth in Botswana. Journal of Economics and Sustainable Development 6: 68–77. [Google Scholar]

- Mirowski, Philip. 1982. What’s Wrong with the Laffer Curve? Journal of Economic Issues 16: 815–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyajima, Ken. 2021. Monetary Policy, Inflation, and Distributional Impact: South Africa’s Case. IMF Working Papers 78: 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mlilo, Mthokozisi, and Matamela Netshikulwe. 2017. Re-testing Wagner’s Law: Structural breaks and disaggregated data for South Africa. Journal of Economics and Behavioral Studies 9: 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monamodi, Nkosinathi. 2019. The Impact of Fiscal and Monetary Policy on Economic Growth in Southern African Custom Union (SACU) Member Economies between 1980 and 2017: A Panel ARDL Approach. SSRN Electronic Journal 15: 86–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mothibi, Lerato, and Precious Mncayi-Makhanya. 2019. Investigating The Key Drivers of Government Debt in South Africa: A Post-Apartheid Analysis. International Journal of eBusiness and eGovernment Studies 11: 16–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moyo, Delani, Ahmed Samour, and Turgut Tursoy. 2021. The Nexus Between Taxation, Government Expenditure and Economic Growth in South Africa. A fresh evidence from combined cointegration test. Studies of Applied Economics 39: 2–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muzekenyi, Mike, Jethro Zuwarimwe, Beata Kilonzo, and Daniel Nheta. 2019. An Assessment of The Role of Real Exchange Rate On Economic Growth In South Africa. Journal Of Contemporary Management 16: 140–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myrdal, Gunnar. 1957. Economic Theory and Underdeveloped Regions. London: Duckworth. [Google Scholar]

- Narayan, Paresh Kumar. 2005. The saving and investment nexus for China: Evidence from cointegration tests. Applied Economics 37: 1979–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Treasury. 2019. Economic Transformation, Inclusive Growth, and Competitiveness: Towards an Economic Strategy for South Africa, Economic Policy; Pretoria: National Treasury.

- Nenovsky, Nikolay. 2011. Criticisms of Classical Political Economy. Menger, Austrian economics and the German Historical School. The European Journal of the History of Economic Thought 18: 290–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nesiba, Reynold. 2013. Do Institutionalists and post-Keynesians share a common approach to Modern Monetary Theory (MMT)? European Journal of Economics and Economic Policies: Intervention 10: 44–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, Hoa Thi, and Susilo Nur Aji Cokro Darsono. 2022. The Impacts of Tax Revenue and Investment on the Economic Growth in Southeast Asian Countries. Journal of Accounting and Investment 23: 128–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noman, Shoayeb, and Mohsan Khudri. 2015. The Effects of Monetary and Fiscal Policies on Economic Growth in Bangladesh. ELK Asia Pacific Journal of Finance and Risk Management 6: 21–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- North, Douglass Cecil. 1990. Institutions, Institutional Change and Economic Performance. The Economic Journal 101: 1587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyasha, Sheilla, and Nicholas Mbaya Odhiambo. 2015. The Impact of Banks and Stock Market Development on Economic Growth in South Africa: An ARDL-bounds Testing Approach. Contemporary Economics 9: 93–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olson, Mancur. 1984. Beyond Keynesianism and Monetarism. Economic Inquiry 22: 297–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palley, Thomas. 1996. Growth Theory in a Keynesian Mode: Some Keynesian Foundations for New Endogenous Growth Theory. Journal of Post Keynesian Economics 19: 113–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palley, Thomas. 2014. Money, Fiscal Policy, and Interest Rates: A Critique of Modern Monetary Theory. Review of Political Economy 27: 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, Deeviya, and Gisele Mah. 2018. Relationship between Real Exchange Rate and Economic Growth: The case of South Africa. Journal of Economics and Behavioral Studies 10: 146–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Permana, Yudistira Hendra, and Gek Sintha Mas Jasmin Wika. 2014. Testing the Existence of Wagner Law and Government Expenditure Volatility in Indonesia Post-Reformation Era. Journal of Economics and Sustainable Development 5: 130–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pesaran, Mohammad Hashem, Yongcheol Shin, and Richard Jay Smith. 2001. Bounds testing approaches to the analysis of level relationships. Journal of Applied Econometrics 16: 289–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, Peter Charles Bonest, and Pierre Perron. 1988. Testing for a unit root in time series regression. Biometrika 75: 335–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Posner, Richard Allen. 2010. From the new institutional economics to organization economics: With applications to corporate governance, government agencies, and legal institutions. Journal of Institutional Economics 6: 1–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramsey, James Bernard. 1969. Tests for Specification Errors in Classical Linear Least-Squares Regression Analysis. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society. Series B (Methodological) 31: 350–71. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/2984219 (accessed on 11 July 2024). [CrossRef]

- Reinhart, Carmen, and Kenneth Rogoff. 2010. Growth in a Time of Debt. National Bureau of Economic Research 100: WP15639. Available online: https://econpapers.repec.org/paper/nbrnberwo/15639.htm (accessed on 24 July 2024).

- Romer, Paul Michael. 1986. Increasing Returns and long-run Growth. Journal of Political Economy 94: 1002–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roşoiu, Iulia. 2015. The Impact of the Government Revenues and Expenditures on the Economic Growth. Procedia Economics and Finance 32: 526–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samuelson, Paul Anthony. 1954. The Pure Theory of Public Expenditure. The Review of Economics and Statistics 36: 387–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sari, Wuri Nur Indah, Eni Setyowati, Sherlyna Mandassari Putri, and Sitti Retno Faridatussalam. 2022. Analysis of the Effect of Interest Rates, Exchange Rate Inflation and Foreign Investment (PMA) on Economic Growth in Indonesia in 1986–2020. Available online: www.atlantis-press.com (accessed on 11 July 2024). [CrossRef]

- Saungweme, Talknice, and Nicholas Mbaya Odhiambo. 2020. Relative Impact of Domestic and Foreign Public Debt on Economic Growth in South Africa. Journal of Applied Social Science 15: 132–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sedrakyan, Gohar Samvel, and Laura Varela-Candamio. 2019. Wagner’s law vs. Keynes’ hypothesis in very different countries (Armenia and Spain). Journal of Policy Modeling 41: 747–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaukat, Badiea, Qigui Zhu, and Muhammad Ijaz Khan. 2019. Real interest rate and economic growth: A statistical exploration for transitory economies. Physica A: Statistical Mechanics and Its Applications 534: 122193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, Adam. 1776. An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations. Readings in Economic Sociology 1: 6–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- So, Alvin, and Alice Hoffenberg Amsden. 2002. The Rise of ‘The Rest’: Challenges to the West from Late-Industrializing Economies. Contemporary Sociology 31: 457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabellini, Guido. 2005. Finn Kydland and Edward Prescott’s Contribution to the Theory of Macroeconomic Policy. Scandinavian Journal of Economics 107: 203–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tcherneva, Pavlina. 2011. Fiscal Policy Effectiveness: Lessons from the Great Recession. Levy Economics Institute Working Paper No. 649. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=1760135 (accessed on 14 July 2024).

- Thabane, Kanono, and Sello Lebina. 2016. Economic Growth and Government Spending Nexus: Empirical Evidence from Lesotho. African Journal of Economic Review 4: 86–100. Available online: https://econpapers.repec.org/RePEc:ags:afjecr:264386 (accessed on 24 July 2024).

- Tilman, Rick. 2008. Institutional Economics as Social Criticism and Political Philosophy. Journal of Economic Issues 42: 289–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, Paul. 2010. Power properties of the CUSUM and CUSUMSQ tests for parameter instability. Applied Economics Letters 17: 1049–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wade, Robert. 1992. East Asia’s Economic Success: Conflicting Perspectives, Partial Insights, Shaky Evidence. World Politics 44: 270–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, Adolph. 1893. Grundlegung der politischen Okonomie, 3rd ed. Leipzig: CF Winter’sche Verlagshandlung. [Google Scholar]

- Williamson, Oliver Eaton. 2000. The New Institutional Economics: Taking Stock, Looking Ahead. Journal of Economic Literature 38: 595–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Diagnostic Test | Explanation | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Q-statistic (correlogram of residuals) | This test detects residual autocorrelation. Autocorrelation violates the assumption of independent and identically distributed errors, resulting in inefficient parameter estimates and invalid statistical inferences. | (Breusch 1978) |

| Jarque–Bera test | The residuals’ normality was determined by this test. For valid statistical inferences, normality is desirable, and violations can affect hypothesis testing and confidence intervals. | Jarque and Bera (1987) |

| Breusch–Godfrey serial correlation LM test | This test detects residual serial correlation. Serial correlation can cause inefficient parameter estimates and biased standard errors, compromising statistical inferences. | Breusch (1978); Godfrey (1978) |

| ARCH-LM test | This test detects residual autoregressive conditional heteroskedasticity (ARCH). Heteroskedasticity, or non-constant residual variance, violates homoskedasticity by causing inefficient parameter estimates and biased standard errors. | Engle (1982) |

| Ramsey’s RESET test | This test has been used to detect model functional form errors consisting of omitted variables. Therefore, model misspecification can bias and inconsistently estimate parameters, undermining inference validity. | Ramsey (1969) |

| Category | Justification |

|---|---|

| Simplicity | The main objective of the study was to evaluate the applicability of specific economic theories (Keynesian, monetarist, Wagner’s) within the context of South Africa. Bivariate analyses facilitate a more straightforward interpretation in relation to these theories. |

| Limitations of sample size | The sample size was relatively small, consisting of annual data from 1980 to 2022. When using multivariate techniques, it is important to have larger samples in order to obtain accurate estimates, particularly when working with multiple variables and lags. |

| Focused on individual relationships | The primary goal was to separate and analyse the impacts of particular fiscal and monetary policy factors on economic growth, which is in line with bivariate methodologies. |

| Interpretability of results | Although multivariate models have the ability to capture complicated interactions, they can pose difficulties in interpretation, particularly when attempting to establish connections with specific economic theories. |

| GDP_Growth | GD | GR | GE | ER | IR | IF | MS | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | 2.100612 | 36.86591 | 21.10909 | 24.24545 | 6.799129 | 4.079011 | 8.504760 | 56.32707 |

| Median | 2.400000 | 32.90000 | 20.80000 | 23.85000 | 6.459693 | 4.027493 | 7.039727 | 51.41957 |

| Maximum | 6.620583 | 70.90000 | 25.30000 | 31.80000 | 16.45911 | 12.69103 | 18.65492 | 73.96950 |

| Minimum | −5.963358 | 23.60000 | 17.90000 | 19.20000 | 0.778834 | −11.00901 | −0.692030 | 41.51655 |

| Std. Dev | 2.531362 | 12.08154 | 1.822829 | 2.897188 | 4.632959 | 3.938838 | 4.609310 | 10.35606 |

| Skewness | −0.735264 | 1.362933 | 0.271571 | 0.617685 | 0.579347 | −0.906002 | 0.430097 | 0.303163 |

| Kurtosis | 3.819556 | 4.384612 | 2.362220 | 2.891934 | 2.253647 | 6.918028 | 2.211543 | 1.452924 |

| Jarque–Bera | 5.077804 | 17.13708 | 1.286571 | 2.819329 | 3.403476 | 33.38646 | 2.439529 | 4.946928 |

| Probability | 0.078953 | 0.000190 | 0.525563 | 0.244225 | 0.182366 | 0.000000 | 0.295300 | 0.084292 |

| GDP_growth | GD | GE | GR | ER | IR | IF | MS | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GDP_growth | 1 | |||||||

| GD | −0.096848 | 1 | ||||||

| GE | −0.269392 | 0.812387 | 1 | |||||

| GR | −0.267875 | 0.502299 | 0.700160 | 1 | ||||

| ER | −0.158253 | 0.742019 | 0.760325 | 0.819210 | 1 | |||

| IR | −0.012185 | 0.132125 | −0.013749 | 0.091029 | 0.108984 | 1 | ||

| IF | −0.202493 | −0.463327 | −0.404467 | −0.437055 | −0.690169 | −0.352175 | 1 | |

| MS | −0.052259 | 0.365677 | 0.557305 | 0.791198 | 0.803753 | −0.019611 | −0.610186 | 1 |

| Levels | Bandwidth | First Difference | Bandwidth | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Test | Intercept | Intercept and Trend | Intercept | Intercept and Trend | ||

| GDP_growth | ADF | 0.0001 | 0.0007 | 0 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0 |

| PP | 0.0001 | 0.0007 | 1 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 15 | |

| KPSS | 0.137440 | 0.136281 | 2 | 0.248329 | 0.173762 | 17 | |

| GD | ADF | 0.8908 | 0.9167 | 1 | 0.0026 | 0.0115 | 0 |

| PP | 0.9884 | 0.9709 | 3 | 0.0026 | 0.0110 | 2 | |

| KPSS | 0.424817 | 0.113154 | 5 | 0.318285 | 0.118215 | 4 | |

| GE | ADF | 0.8977 | 0.8512 | 0 | 0.0000 | 0.0001 | 0 |

| PP | 0.8898 | 0.8237 | 2 | 0.0000 | 0.0001 | 0 | |

| KPSS | 0.549794 | 0.134248 | 5 | 0.146435 | 0.088135 | 0 | |

| GR | ADF | 0.4104 | 0.0353 | 0 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0 |

| PP | 0.5682 | 0.0324 | 2 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 10 | |

| KPSS | 0.741252 | 0.082962 | 2 | 0.139263 | 0.124831 | 12 | |

| ER | ADF | 0.9722 | 0.5244 | 0 | 0.0000 | 0.0001 | 0 |

| PP | 0.9909 | 0.4992 | 3 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 11 | |

| KPSS | 0.782595 | 0.124273 | 4 | 0.197999 | 0.100508 | 10 | |

| IR | ADF | 0.0000 | 0.0005 | 0 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0 |

| PP | 0.0000 | 0.0006 | 2 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 17 | |

| KPSS | 0.224226 | 0.178522 | 4 | 0.159466 | 0.060718 | 1 | |

| IF | ADF | 0.7685 | 0.9396 | 4 | 0.0000 | 0.0003 | 3 |

| PP | 0.4618 | 0.2488 | 7 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 40 | |

| KPSS | 0.654993 | 0.168431 | 4 | 0.472595 | 0.412194 | 35 | |

| MS | ADF | 0.9159 | 0.6348 | 0 | 0.0001 | 0.0004 | 0 |

| PP | 0.8920 | 0.5591 | 2 | 0.0001 | 0.0004 | 0 | |

| KPSS | 0.691223 | 0.116852 | 5 | 0.134449 | 0.090509 | 1 | |

| Dependent Variable | Model | F-Statistic | Results | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| lnGDP_growth | F(lnGDP_growth/lnGD,lnGE,lnGR) | 15.13923 | Long-run relationship exists (cointegrated) | |||

| Asymptotic critical values | ||||||

| Pesaran et al. (2001), p300, Table CI(iii) Case III | 10% | 5% | 1% | |||

| I(0) | I(1) | I(0) | I(1) | I(0) | I(1) | |

| 2.37 | 3.2 | 2.79 | 3.67 | 3.65 | 4.66 | |

| Variables | Coefficient | Std. Error | t-Statistic | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| C | 26.07530 | 0.893663 | −0.715859 | 0.4828 |

| lnGD | −0.639736 | 4.125634 | −1.381635 | 0.1831 |

| lnGE | −5.700121 | 3.427453 | −0.465347 | 0.6470 |

| lnGR | −1.594955 | 6.763398 | 3.855355 | 0.0011 |

| Types of Tests | Test Statistic | p-Value | Results |

|---|---|---|---|

| Q-statistic (correlogram of residuals) | 2.0631 | 0.151 | Failed to reject the null hypothesis |

| Jarque–Bera | 9.724982 | 0.007731 | Rejected the null hypothesis |

| Breusch–Godfrey serial correlation LM TEST | 3.534188 | 0.0521 | Failed to reject the null hypothesis |

| ARCH-LM | 0.030548 | 0.9700 | Failed to reject the null hypothesis |

| Ramsey (RESET) test | 0.456900 | 0.6408 | Failed to reject the null hypothesis |

| Variable | Coefficient | Uncentred VIF | Centred VIF |

|---|---|---|---|

| lnGD | 9.173567 | 10456.72 | 45.66605 |

| lnGE | 33.55271 | 29,876.56 | 25.44620 |

| lnGR | 17.37699 | 14,227.95 | 7.271898 |

| C | 44.47521 | 3882.892 | N/A |

| Dependent Variable | Model | F-Statistic | Results | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| lnGDP_growth | F(lnGDP_growth/lnER,lnIF,lnIR,lnMS) | 1.949471 | No long-run relationship exists (i.e., no cointegration) | |||

| Asymptotic critical values | ||||||

| Pesaran et al. (2001), p300, Table CI(iii) Case III | 10% | 5% | 1% | |||

| I(0) | I(1) | I(0) | I(1) | I(0) | I(1) | |

| 2.2 | 3.09 | 2.56 | 3.49 | 3.29 | 4.37 | |

| Variable | Coefficient | Std. Error | t-Statistic | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| D (lnER) | −2.452820 | 1.807068 | −1.357348 | 0.1962 |

| D (lnIF) | 0.036032 | 0.707189 | 0.050951 | 0.9601 |

| D (lnIR) | −0.705642 | 0.605676 | −1.165048 | 0.2635 |

| D (lnMS) | −3.031129 | 5.401375 | −0.561177 | 0.5835 |

| C | 0.169461 | 0.253142 | 0.669431 | 0.5141 |

| R-squared: 0.231172 Adjusted R-squared: −0.043410 F-Statistic: 0.841906 Prob (F-statistic): 0.542060 Durbin–Watson stat: 2.039134 | ||||

| Types of Tests | Test Statistic | p-Value | Results |

|---|---|---|---|

| Q-statistic (correlogram of residuals) | 0.1557 | 0.693 | Failed to reject the null hypothesis |

| Jarque–Bera | 15.22767 | 0.000494 | Rejected the null hypothesis of normality |

| Breusch–Godfrey serial correlation LM TEST | 1.349047 | 0.2845 | Failed to reject the null hypothesis of no serial correlation |

| ARCH-LM | 0.084875 | 0.9191 | Failed to reject the null hypothesis of no heteroskedasticity |

| Ramsey (RESET) test | 0.763647 | 0.4805 | Failed to reject the null hypothesis of no omitted variables or incorrect functional form |

| Variable | Coefficient Variance | Uncentred VIF | Centred VIF |

|---|---|---|---|

| lnER | 0.119001 | 31.63596 | 2.949770 |

| lnIF | 0.141504 | 31.70879 | 1.560107 |

| lnIR | 0.099947 | 17.35206 | 1.373689 |

| lnMS | 1.509091 | 1568.607 | 2.810526 |

| C | 24.99751 | 1578.308 | N/A |

| Level | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependant Variable | Null Hypothesis | Observations | F-Statistic | p-Value | Decision (Accept or Reject Hypothesis) |

| lnGDP_growth | lnGD does not Granger-cause lnGDP_growth | 24 | 2.5292 | 0.1062 | Accepted |

| lnGDP_growth does Granger-cause lnGD | 2.5441 | 0.1050 | Accepted | ||

| lnGE does not Granger-cause lnGDP_growth | 6.9860 | 0.0053 | Rejected | ||

| lnGDP_growth does Granger-cause lnGE | 0.1443 | 0.8666 | Accepted | ||

| lnGR does not Granger-cause lnGDP_growth | 2.3729 | 0.1203 | Accepted | ||

| lnGDP_growth does Granger-cause lnGR | 0.9173 | 0.4166 | Accepted | ||

| First Difference | |||||

| D(lnGDP_growth) | D(lnGD) does not Granger-cause D(lnGDP_growth) | 21 | 0.2856 | 0.7552 | Accepted |

| D(lnGDP_growth) does Granger-cause D(lnGD) | 0.8746 | 0.4361 | Accepted | ||

| D(lnGE) does not Granger-cause D(lnGDP_growth) | 1.1117 | 0.3531 | Accepted | ||

| D(lnGDP_growth) does Granger-cause D(lnGE) | 0.3932 | 0.6812 | Accepted | ||

| D(lnGR) does not Granger-cause D(lnGDP_growth) | 0.0698 | 0.4935 | Accepted | ||

| D(lnGDP_growth) does Granger-cause (lnGR) | 0.7383 | 0.4935 | Accepted | ||

| Level | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dependant Variable | Null Hypothesis | Observations | F-Statistic | p-Value | Decision (Accept or Reject Null Hypothesis) |

| lnGDP_growth | lnER does not Granger-cause lnGDP_growth | 24 | 0.97187 | 0.3964 | Accepted |

| lnGDP_growth does Granger-cause lnER | 0.06236 | 0.9397 | Accepted | ||

| lnIF does not Granger-cause lnGDP_growth | 21 | 0.20088 | 0.8200 | Accepted | |

| lnGDP_growth does Granger-cause lnIF | 4.63940 | 0.0258 | Rejected | ||

| lnIR does not Granger-cause lnGDP_growth | 22 | 0.14434 | 0.8666 | Accepted | |

| lnGDP_growth does Granger-cause lnIR | 0.13514 | 0.8745 | Accepted | ||

| lnMS does not Granger-cause lnGDP_growth | 24 | 0.85153 | 0.4424 | Accepted | |

| lnGDP_growth does Granger-cause lnMS | 1.99807 | 0.1631 | Accepted | ||

| First Difference | |||||

| D(lnGDP_growth) | D(lnER) does not Granger-cause D(lnGDP_growth) | 21 | 0.08379 | 0.9200 | Accepted |

| D(lnGDP_growth) does Granger-cause D(lnER) | 0.31191 | 0.7364 | Accepted | ||

| D(lnIF) does not Granger-cause D(lnGDP_growth) | 17 | 0.35588 | 0.7077 | Accepted | |

| D(lnGDP_growth) does Granger-cause D(lnIF) | 0.76521 | 0.4867 | Accepted | ||

| D(lnIR) does not Granger-cause D(lnGDP_growth) | 20 | 0.84234 | 0.4501 | Accepted | |

| D(lnGDP_growth) does Granger-cause (lnIR) | 0.63239 | 0.5449 | Accepted | ||

| D(lnMS) does not Granger-cause D(lnGDP_growth) | 21 | 0.25454 | 0.7784 | Accepted | |

| D(lnGDP_growth) does Granger-cause (lnMS) | 0.39542 | 0.6798 | Accepted | ||

| Category | Justification |

|---|---|

| Omitted-variable bias | Bivariate analysis fails to consider the impact of additional variables, potentially resulting in misleading correlations or concealing genuine relationships. |

| Secondary impacts | When compared to bivariate analysis, multivariate analysis has the potential to uncover additional indirect relationships between variables that are not readily apparent. |

| Complex relationships between the employed variables | The economy is a complicated system that is composed of a number of variables that interact with one another. It is possible that bivariate analysis causes these relationships to be oversimplified, which can result in contradictory findings when different pairs of variables are investigated separately. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Majenge, L.; Mpungose, S.; Msomi, S. Econometric Analysis of South Africa’s Fiscal and Monetary Policy Effects on Economic Growth from 1980 to 2022. Economies 2024, 12, 227. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies12090227

Majenge L, Mpungose S, Msomi S. Econometric Analysis of South Africa’s Fiscal and Monetary Policy Effects on Economic Growth from 1980 to 2022. Economies. 2024; 12(9):227. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies12090227

Chicago/Turabian StyleMajenge, Luyanda, Sakhile Mpungose, and Simiso Msomi. 2024. "Econometric Analysis of South Africa’s Fiscal and Monetary Policy Effects on Economic Growth from 1980 to 2022" Economies 12, no. 9: 227. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies12090227

APA StyleMajenge, L., Mpungose, S., & Msomi, S. (2024). Econometric Analysis of South Africa’s Fiscal and Monetary Policy Effects on Economic Growth from 1980 to 2022. Economies, 12(9), 227. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies12090227