The Structure and Nature of Social Capital in the Relationship between Spin-Offs and Parent Companies in Information Technology Clusters in Brazil and Spain

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Social Capital, Innovation, and Spin-Off in Clusters: Theoretical Proposal and Hypotheses

3. Materials and Methods

4. Results and Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | Geographic proximity refers to the physical space in which a business agglomeration or cluster is defined (Balland et al. 2022). |

References

- Agarwal, Rajshree, Raj Echambadi, April M. Franco, and Mitra Barun Sarkar. 2004. Knowledge Transfer Through Inheritance: Spin-Out Generation, Development, and Survival. Academy of Management Journal 47: 501–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anand, Vikas, William H. Glick, and Charles C. Manz. 2002. Thriving on the knowledge of outsiders: Tapping organizational social capital. Academy of Management Perspectives 16: 87–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, Martin, Apostolos Baltzopoulos, and Hans Lööf. 2012. R&D strategies and entrepreneurial spawning. Research Policy 41: 54–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrighi, Fabiela Fatima, Valmir Emil Hoffmann, and Marcos Antonio Ribeiro Andrade. 2011. Análise Da Produção Científica No Campo De Estudo Das Redes Em Periódicos Nacionais E Internacionais. Revista de Administração e Inovação-RAI 8: 29–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arbuckle, James L. 2013. IBM SPSS Amos 22 User’s Guide. Crawfordville: Amos Development Corporation. [Google Scholar]

- Audretsch, David. B., T. Taylor Aldridge, and Mark Sanders. 2011. Social capital building and new business formation: A case study in Silicon Valley. International Small Business Journal 29: 152–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagley, Mark J. O. 2019a. Networks, geography and the survival of the firm. Journal of Evolutionary Economics 29: 1173–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagley, Mark J. O. 2019b. Small worlds, inheritance networks and industrial clusters. Industry and Innovation 26: 741–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balland, Pierre-Alexandre, Ron Boschma, and Koen Frenken. 2022. Proximity, Innovation and Networks: A Concise Review and Some Next Steps. In Handbook of Proximity Relations. Edited by André Torre and Delphine Gallaud. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar, pp. 70–90. [Google Scholar]

- Barcelona City Council. 2012. ICT Sector in Barcelona. Available online: http://barcelonacatalonia.cat/b/wp-content/uploads/2012/12/eng-ICT-23-03.pdf (accessed on 22 August 2015).

- Byrne, Barbara M. 2010. Structural Equation Modeling with AMOS: Basic Concepts, Applications, and Programming, 2nd ed. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Cardoso, Flávio Manoel Coelho Borges, Valmir Emil Hoffmann, and María Teresa Martínez-Fernández. 2019. Spin-offs and clusters: An application to the information technology sector in Brazil and Spain. In Economic Clusters and Globalization: Diversity and Resilience. Routledge Advances in Regional Economics, Science and Policy. New York: Routledge, pp. 97–110. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Xiaofei, Enru Wang, Changhong Miao, Lili Ji, and Shaoqi Pan. 2020. Industrial Clusters as Drivers of Sustainable Regional Economic Development? An Analysis of an Automotive Cluster from the Perspective of Firms’ Role. Sustainability 12: 2848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chesbrough, Henry. 2003. The governance and performance of Xerox’s technology spin-off companies. Research Policy 32: 403–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahlstrand, Åsa Lindholm. 1997. Entrepreneurial spin-off enterprises in Göteborg, Sweden. European Planning Studies 5: 659–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Figueiredo, Rui J. P., Philipp Meyer-Doyle, and Evan Rawley. 2013. Inherited agglomeration effects in hedge fund spawns. Strategic Management Journal 34: 843–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del-Corte-Lora, Víctor, Teresa Maria Vallet-Bellmunt, and F. Xavier Molina-Morales. 2017. How network position interacts with the relation between creativity and innovation in clustered firms. European Planning Studies 25: 561–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eiriz, Vasco, and Natália Barbosa. 2022. SMEs’ Strategic Responses to a Multinational’s Entry Into a Cluster. Journal of Small Business Strategy 32: 126–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fryges, Helmut, Bettina Müller, and Michaela Niefert. 2014. Job machine, think tank, or both: What makes corporate spin-offs different? Small Business Economics 43: 369–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furlan, Andrea, and Giulio Cainelli. 2020. Spinoffs or startups? The effects of spatial agglomeration. Industrial and Corporate Change 29: 1451–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glasmeier, Amy. 1991. Technological discontinuities and flexible production networks: The case of Switzerland and the world watch industry. Research Policy 20: 469–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granovetter, Mark. 1973. The strength of weak ties. American Journal of Sociology 78: 1360–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granovetter, Mark. 1983. The strength of weak ties: A network theory revisited. Sociological Theory 1: 201–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granovetter, Mark. 1985. Economic Action and Social Structure: The Problem of Embeddedness. American Journal of Sociology 91: 481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Feng, Zhaowei Zhu, and Sharafat Ali. 2023. Analysis of Factors of Single-Use Plastic Avoidance Behavior for Environmental Sustainability in China. Processes 11: 1412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, Joseph F., Rolph E. Anderson, Ronald L. Tatham, and William C. Black. 2005. Análise Multivariada de Dados, 5th ed. Porto Alegre: Bookman. [Google Scholar]

- Håkansson, Håkan, and Ivan Snehota. 1995. Developing Relationships in Business Networks. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Håkansson, Håkan, and Ivan Snehota. 2006. No business is an island: The network concept of business strategy. Scandinavian Journal of Management 22: 256–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halbert, Ludovic. 2012. Collaborative and Collective: Reflexive Co-ordination and the Dynamics of Open Innovation in the Digital Industry Clusters of the Paris Region. Urban Studies 49: 2357–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hite, Julie M. 2003. Patterns of Multidimensionality among Embedded Network Ties: A Typology of Relational Embeddedness in Emerging Entrepreneurial Firms. Strategic Organization 1: 9–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, Valmir Emil, and Lucila Maria de Souza Campos. 2013. Instituições de Suporte, Serviços e Desempenho: Um Estudo em Aglomeração Turística de Santa Catarina. Revista de Administração Contemporânea 17: 18–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, Valmir Emil, Fiorenza Belussi, F. Xavier Molina, and Daniel V. Pires. 2023. Clusters under pressure: The impact of a crisis in Italian industrial districts. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development 35: 424–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, Valmir Emil, Gisele Silveira Coelho Lopes, and Janann Joslin Medeiros. 2014. Knowledge transfer among the small businesses of a Brazilian cluster. Journal of Business Research 67: 856–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofstede, Geert. 1983. The Cultural Relativity of Organizational Practices and Theories. Journalof International Business Studies 14: 75–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- d’Iribarne, Philippe. 2009. National Cultures and Organisations in Search of a Theory: An Interpretative Approach. International Journal of Cross Cultural Management 9: 309–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juhász, Sándor. 2021. Spinoffs and tie formation in cluster knowledge networks. Small Business Economics 56: 1385–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerr, William R., and Frederic Robert-Nicoud. 2020. Tech clusters. Journal of Economic Perspectives 34: 50–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Kyung Kyu, Seung Hoon Park, Sung Yul Ryoo, and Sung Kook Park. 2010. Inter-organizational cooperation in buyer-supplier relationships: Both perspectives. Journal of Business Research 63: 863–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klepper, Steven. 2011. Nano-economics, spinoffs, and the wealth of regions. Small Business Economics 37: 141–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, Rex B. 2011. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling, 3rd ed. New York: The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Laros, Jacob A. 2005. O uso da análise fatorial: Algumas diretrizes para pesquisadores. In Análise fatorial para pesquisadores. Edited by Luis Pasqualli. Brasília: LabPAM, pp. 163–93. [Google Scholar]

- Lattin, James M., J. Douglas Carroll, and Paul E. Green. 2011. Análise multivariada de dados. São Paulo: Cengage Learning. [Google Scholar]

- Lazzarotti, Fábio, Alissane Lia Tasca da Silveira, Carlos Eduardo Carvalho, Carlos Ricardo Rossetto, and Jonatha Correia Sychoski. 2015. Orientação Empreendedora: Um Estudo das Dimensões e sua Relação com Desempenho em Empresas Graduadas. Revista de Administração Contemporânea 19: 673–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Choonwoo, Kyungmook Lee, and Johannes M. Pennings. 2001. Internal capabilities, external networks, and performance: A study on technology-based ventures. Strategic Management Journal 22: 615–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Iturriaga, Félix, and Natalia Martín-Cruz. 2008. Antecedents of corporate spin-offs in Spain: A resource-based approach. Research Policy 37: 1047–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lumpkin, G. Tom, and Gregory G. Dess. 1996. Clarifying the entrepreneurial orientation construct and linking it to performance. Academy of Management Review 21: 135–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marôco, João. 2014. Análise de Equações Estruturais: Fundamentos Teóricos, Software & Aplicações, 2nd ed. Pêro Pinheiro-Portugal: ReportNumber. [Google Scholar]

- Maurer, Indre, and Mark Ebers. 2006. Dynamics of Social Capital and Their Performance Implications: Lessons from Biotechnology Start-ups. Administrative Science Quarterly 51: 262–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKendrick, David G., James B. Wade, and Jonathan Jaffee. 2009. A Good Riddance? Spin-Offs and the Technological Performance of Parent Firms. Organization Science 20: 979–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, Danny. 1983. The correlates of entrepreneurship in three types of firms. Management Science 29: 770–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina, Francesc Xavier, M. Teresa Martínez-Fernández, Maria Ares Vázquez, and Valmir Emil Hoffmann. 2008. La estructura y naturaleza del capital social en las aglomeraciones territoriales de empresas: Una aplicación al sector cerámico español. Bilbao: Fundación BBVA. [Google Scholar]

- Molina-Morales, Francesc Xavier, Josep Capó-Vicedo, Maria Teresa Martínez-Fernández, and Manuel Expósito-Langa. 2013. Social capital in industrial districts: Influence of the strength of ties and density of the network on the sense of belonging to the district. Papers in Regional Science 92: 773–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadvi, Khalid. 1999. Shifting ties: Social networks in the surgical instrument cluster of Sialkot, Pakistan. Development and Change 30: 141–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nahapiet, Janine, and Sumantra Ghoshal. 1998. Social capital, intellectual capital, and the organizational advantage. Academy of Management Review 23: 242–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nooteboom, Bart. 2006. Innovation, learning and cluster dynamics. In Clusters and Regional Development: Critical Reflections and Explorations. Edited by Philip Cooke Bjorn Asheim Philip Cooke and Ron Martin. New York: Routledge, pp. 320–20. [Google Scholar]

- Oliver, Christine. 1990. Determinants of interorganizational relationships: Integration and future directions. Academy of Management Review 15: 241–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oudeniotis, Nectarios, and George O. Tsobanoglou. 2022. Interorganizational Cooperation and Social Capital Formation among Social Enterprises and Social Economy Organizations: A Case Study from the Region of Attica, Greece. Social Sciences 11: 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padilla-Melendez, Antonio, Ana Rosa Del Aguila-Obra, and Nigel Lockett. 2012. Shifting sands: Regional perspectives on the role of social capital in supporting open innovation through knowledge transfer and exchange with small and medium-sized enterprises. International Small Business Journal 31: 296–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parga-Montoya, Neftali, and Héctor Cuevas-Vargas. 2023. The influence of network ties on entrepreneurial orientation in Mexican farmers: An institutional perspective. Revista de Administração Mackenzie 24: 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parhankangas, Annaleena, and Hans Landström. 2006. How venture capitalists respond to unmet expectations: The role of social environment. Journal of Business Venturing 21: 773–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parhankangas, Annaleena, and Pia Arenius. 2003. From a corporate venture to an independent company: A base for a taxonomy for corporate spin-off firms. Research Policy 32: 463–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perlines, Felipe Hernández. 2014. Orientación emprendedora de las cooperativas agroalimentarias con actividad exportadora. CIRIEC-España, Revista de Economía Pública, Social y Cooperativa 80: 29–55. [Google Scholar]

- Podsakoff, Philip M., Scott B. MacKenzie, Jeong-Yeon Lee, and Nathan P. Podsakoff. 2003. Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology 88: 879–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sapienza, Harry J., Annaleena Parhankangas, and Erkko Autio. 2004. Knowledge relatedness and post-spin-off growth. Journal of Business Venturing 19: 809–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saxenian, Annalee. 1996. Regional Advantage: Culture and Competition in Silicon Valley and Route 128. Cambridge: Harvard Business School Press. [Google Scholar]

- Soda, Giuseppe, and Akbar Zaheer. 2012. A network perspective on organizational architecture: Performance effects of the interplay of formal and informal organization. Strategic Management Journal 33: 751–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stam, Wouter, and Tom Elfring. 2008. Entrepreneurial orientation and new venture performance: The moderating role of intra- and extraindustry social capital. Academy of Management Journal 51: 97–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stenmark, Dick. 2002. Information vs. knowledge: The role of intranets in knowledge management. Paper presented at the 35th Annual Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, Big Island, HI, USA, January 7–10. [Google Scholar]

- Torres, Ariana, Michael S. Delgado, and Maria I. Marshall. 2021. The economic implications of clustering on Hispanic entrepreneurship in the US. Journal of Small Business Strategy 31: 72–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatraman, N. Venkat. 1989. Strategic orientation of business enterprises: The construct, dimensionality and measurement. Management Science 35: 942–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viladecans-Marsal, Elisabet, and Josep Maria Arauzo-Carod. 2012. Can a knowledge-based cluster be created? The case of the Barcelona 22at district. Papers in Regional Science 91: 377–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahyuni, Ni Made, and I. Made Sara. 2020. The effect of entrepreneurial orientation variables on business performance in the SME industry context. Journal of Workplace Learning 32: 35–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallin, Martin W. 2012. The bibliometric structure of spin-off literature. Innovation: Management, Policy & Practice 14: 162–77. [Google Scholar]

- Wiklund, Johan, and Dean Shepherd. 2005. Entrepreneurial orientation and small business performance: A configurational approach. Journal of Business Venturing 20: 71–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaheer, Akbar, Remzi Gozubuyuk, and Hana Milanov. 2010. It’s the connections: The networks perspective in interorganizational research. The Academy of Management Perspectives 24: 62–77. [Google Scholar]

| Variables | Indicators |

|---|---|

| Density of the relationship (Density) | Degree of knowledge and information overlap; degree of interconnection and dependence that the firm has on this network to obtain these resources. |

| Strength of ties (Strength) | Intimacy (proximity of contact); frequency (number of times of contact); to the extent that managers and workers have already worked in other companies in the same area of the cluster. |

| Rich exchange of information and knowledge (Rich) | Quality information and tacit knowledge; organizational learning; information more relevant and detailed than that of the market. |

| Common norms and values (norms) | Trust, reputation, reciprocity, and conflict resolution without legal proceedings and no contractual regulation between companies. |

| Local institutions (institutions) | Number of positions or important positions in the associations; importance for obtaining information and knowledge; and for innovation. |

| Entrepreneurial orientation * (Orientation) | Innovative capacity, proactivity, and risk-taking. |

| Innovation (Performance) | Number of patents and other property rights; contracts; number of new products; technologies used; number of product or firm certifications and introduction of improved processes; evaluation of innovation in relation to its competitors. |

| Construct | Observ. Variable | Min. * | Max. * | Inf. Lim. ** | Mean | Upper Limit ** | Mn | Stand. Dev. | Kurt. | Asym. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Density of the Relationship | P2_1 | −1.86 | 1.58 | 4.02 | 4.25 | 4.48 | 4 | 1.74 | −0.273 | −0.939 |

| P2_2 | −1.99 | 1.30 | 4.39 | 4.63 | 4.87 | 5 | 1.82 | −0.460 | −0.958 | |

| P2_3 | −1.99 | 1.49 | 4.21 | 4.44 | 4.66 | 5 | 1.72 | −0.280 | −0.908 | |

| P2_4 | −2.09 | 1.54 | 4.24 | 4.46 | 4.67 | 5 | 1.65 | −0.346 | −0.818 | |

| Strength of Ties | P3_1 | −2.73 | 1.11 | 5.07 | 5.27 | 5.47 | 6 | 1.56 | −1.086 | 0.581 |

| P3_2 | −2.22 | 1.26 | 4.60 | 4.82 | 5.05 | 5 | 1.72 | −0.568 | −0.719 | |

| P3_3 | −2.22 | 1.39 | 4.47 | 4.69 | 4.91 | 5 | 1.67 | −0.634 | −0.314 | |

| P3_4 | −1.07 | 1.75 | 2.99 | 3.27 | 3.55 | 3 | 2.13 | 0.426 | −1.223 | |

| Rich exchange of Information and Knowledge | P4_1 | −2.06 | 1.50 | 4.25 | 4.47 | 4.69 | 5 | 1.69 | −0.374 | −0.896 |

| P4_2 | −1.94 | 1.53 | 4.12 | 4.35 | 4.58 | 5 | 1.73 | −0.315 | −1.002 | |

| P4_3 | −2.07 | 1.49 | 4.27 | 4.49 | 4.71 | 5 | 1.68 | −0.350 | −0.793 | |

| P4_4 | −1.84 | 1.41 | 4.16 | 4.40 | 4.64 | 5 | 1.84 | −0.290 | −1.191 | |

| Common norms and values | P5_1 | −3.33 | 1.03 | 5.40 | 5.58 | 5.76 | 6 | 1.38 | −1.371 | 1.883 |

| P5_2 | −2.49 | 1.16 | 4.88 | 5.09 | 5.31 | 6 | 1.65 | −0.852 | −0.165 | |

| P5_3 | −4.00 | 1.04 | 5.60 | 5.76 | 5.91 | 6 | 1.19 | −1.704 | 3.871 | |

| P5_4 | −4.42 | 0.99 | 5.55 | 5.72 | 5.89 | 6 | 1.29 | −1.889 | 4.515 | |

| Performance | P6_1 | −0.63 | 2.06 | 2.12 | 2.41 | 2.70 | 1 | 2.23 | 1.234 | −0.124 |

| P6_2 | −0.70 | 1.90 | 2.31 | 2.61 | 2.91 | 1 | 2.31 | 1.025 | −0.596 | |

| P6_3 | −1.32 | 1.91 | 3.21 | 3.45 | 3.70 | 3 | 1.86 | 1.044 | −0.454 | |

| P6_4 | −1.27 | 1.57 | 3.41 | 3.69 | 3.97 | 3 | 2.12 | 0.550 | −1.165 | |

| P6_5 | −1.63 | 1.39 | 3.99 | 4.25 | 4.51 | 4 | 1.99 | −0.025 | −1.151 | |

| P6_6 | −0.93 | 1.99 | 2.65 | 2.92 | 3.18 | 3 | 2.05 | 0.698 | −0.645 | |

| P6_7 | −1.80 | 1.81 | 3.24 | 3.50 | 3.75 | 4 | 1.94 | 0.131 | −1.108 | |

| P6_8 | −3.20 | 1.35 | 5.05 | 5.22 | 5.40 | 5 | 1.32 | −0.642 | 0.049 | |

| P6_9 | −3.25 | 0.99 | 5.42 | 5.60 | 5.79 | 6 | 1.42 | −1.333 | 1.382 | |

| P6_10 | −2.10 | 1.74 | 4.08 | 4.28 | 4.49 | 4 | 1.56 | −0.254 | −0.496 | |

| P6_11 | −2.95 | 1.52 | 4.78 | 4.96 | 5.13 | 5 | 1.34 | −0.551 | 0.028 | |

| P6_12 | −2.81 | 1.60 | 4.65 | 4.83 | 5.00 | 5 | 1.36 | −0.577 | 0.066 | |

| P6_13 | −4.39 | 1.10 | 5.65 | 5.80 | 5.94 | 6 | 1.09 | −1.524 | 3.544 | |

| Local institutions | P7_1 | −1.31 | 1.93 | 3.19 | 3.43 | 3.67 | 3 | 1.85 | 0.346 | −0.496 |

| P7_2 | −0.67 | 2.53 | 2.01 | 2.26 | 2.50 | 1 | 1.88 | 1.204 | 0.169 | |

| P7_3 | −2.16 | 1.50 | 3.88 | 4.13 | 4.38 | 4 | 1.91 | −0.243 | −1.081 | |

| P7_4 | −1.98 | 1.94 | 3.31 | 3.54 | 3.77 | 4 | 1.79 | 0.171 | −1.017 | |

| P7_5 | −1.96 | 2.10 | 3.16 | 3.38 | 3.61 | 3 | 1.72 | 0.138 | −0.991 | |

| P7_6 | −1.98 | 2.05 | 3.21 | 3.44 | 3.67 | 3 | 1.74 | 0.239 | −0.844 | |

| Entrepreneurial orientation | P8_1 | −2.77 | 1.15 | 5.03 | 5.23 | 5.44 | 6 | 1.53 | −0.935 | 0.117 |

| P8_2 | −2.31 | 1.43 | 4.50 | 4.71 | 4.92 | 5 | 1.61 | −0.486 | −0.676 | |

| P8_3 | −2.64 | 1.30 | 4.82 | 5.02 | 5.22 | 5 | 1.52 | −0.785 | −0.067 | |

| P8_4 | −3.27 | 1.15 | 5.26 | 5.44 | 5.62 | 6 | 1.36 | −0.963 | 0.329 | |

| P8_5 | −3.54 | 1.17 | 5.34 | 5.51 | 5.68 | 6 | 1.28 | −1.077 | 0.835 | |

| P8_6 | −2.66 | 1.25 | 4.88 | 5.08 | 5.29 | 5 | 1.54 | −0.735 | −0.161 | |

| P8_7 | −1.86 | 1.85 | 3.80 | 4.01 | 4.22 | 4 | 1.61 | 0.030 | −0.895 | |

| P8_8 | −2.02 | 1.68 | 4.06 | 4.27 | 4.49 | 4 | 1.62 | −0.239 | −0.739 | |

| P8_9 | −1.48 | 2.11 | 3.26 | 3.48 | 3.70 | 3 | 1.67 | 0.312 | −0.736 | |

| P8_10 | −1.97 | 2.04 | 3.75 | 3.95 | 4.15 | 4 | 1.50 | 0.102 | −0.635 | |

| P8_11 | −2.06 | 1.46 | 4.29 | 4.51 | 4.74 | 5 | 1.71 | −0.259 | −1.040 | |

| P8_12 | −2.58 | 1.50 | 4.60 | 4.79 | 4.98 | 5 | 1.47 | −0.427 | −0.568 | |

| P8_13 | −1.55 | 1.61 | 3.70 | 3.95 | 4.19 | 4 | 1.90 | −0.025 | −1.264 | |

| P8_14 | −2.87 | 1.39 | 4.86 | 5.04 | 5.23 | 5 | 1.41 | −0.693 | 0.162 |

| Models | Index | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| χ | GL | χ2/GL | CFI | RMSEA | RMSEA90 * | TLI | |

| Original | 2843.309 | 1124 | 2.530 | 0.693 | 0.082 | 0.078–0.086 | 0.679 |

| 2nd Adjustment | 1184.449 | 557 | 2.126 | 0.854 | 0.071 | 0.065–0.076 | 0.844 |

| Original Country | 4672.108 | 2248 | 2.078 | 0.629 | 0.069 | 0.069–0.072 | 0.612 |

| 2nd Grant Country | 2025.786 | 1114 | 1.818 | 0.810 | 0.060 | 0.056–0.065 | 0.797 |

| 2nd Class Assistance | 2341.999 | 1114 | 2.102 | 0.735 | 0.070 | 0.066–0.074 | 0.717 |

| Reference Values | - | - | 1 a 5 | Closer to 1. the better. | ≤0.08 | - | Closer to 1. the better. |

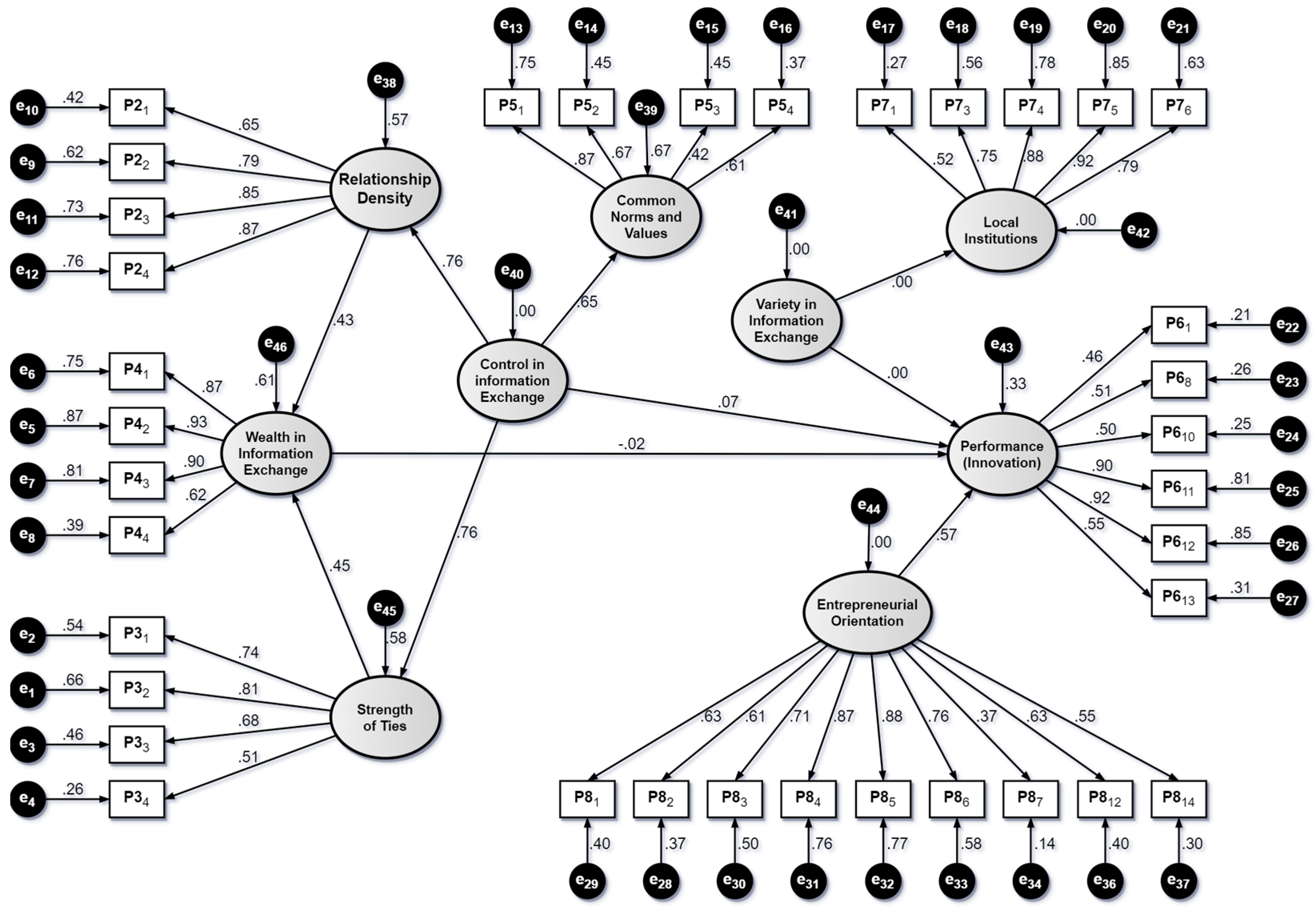

| Estimation | Standard Errors. IF | CR | p Value | Standardized Regression Estimation | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Density | <-- | Control | 1.157 | 0.124 | 9.341 | *** | 0.757 |

| Strength | <-- | Control | 1.17 | 0.119 | 9.858 | *** | 0.76 |

| Wealth | <-- | Density | 0.447 | 0.088 | 5.099 | *** | 0.428 |

| Wealth | <-- | Bond | 0.468 | 0.091 | 5.143 | *** | 0.451 |

| Norms | <-- | Control | 0.853 | 0.1 | 8.509 | *** | 0.649 |

| Performance | <-- | Orientation | 0.695 | 0.094 | 7.435 | *** | 0.57 |

| Performance | <-- | Variety | 0 | 0.258 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Institutions | <-- | Variety | 0 | 0.486 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Performance | <-- | Control | 0.093 | 0.131 | 0.711 | 0.477 | 0.076 |

| Performance | <-- | Wealth | −0.018 | 0.074 | −0.237 | 0.813 | −0.023 |

| Variables | Parent Company | Nonparent Company | Comparation | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate | p-Value | Estimate | p-Value | z Test | |||

| Density | <--- | Control | 0.407 | 0.133 | 1.114 | *** | 2.332 ** |

| Bond | <--- | Control | 0.42 | 0.153 | 1.104 | *** | 2.126 ** |

| Wealth | <--- | Density | 0.312 | 0.199 | 0.513 | *** | 0.768 |

| Wealth | <--- | Bond | 0.813 | 0.001 ** | 0.356 | *** | −1.681 * |

| Norms | <--- | Control | 0.24 | 0.321 | 0.853 | *** | 2.3 ** |

| Performance | <--- | Orietation | 0.768 | 0.004 ** | 0.671 | *** | −0.34 |

| Performance | <--- | Variety | −0.17 | 0.623 | 0.114 | 0.643 | 0.67 |

| Institutions | <--- | Variety | 0.416 | 0.457 | 0.18 | 0.627 | −0.351 |

| Performance | <--- | Control | 0.283 | 0.441 | 0.068 | 0.611 | −0.549 |

| Performance | <--- | Wealth | −0.257 | 0.21 | 0.012 | 0.875 | 1.225 |

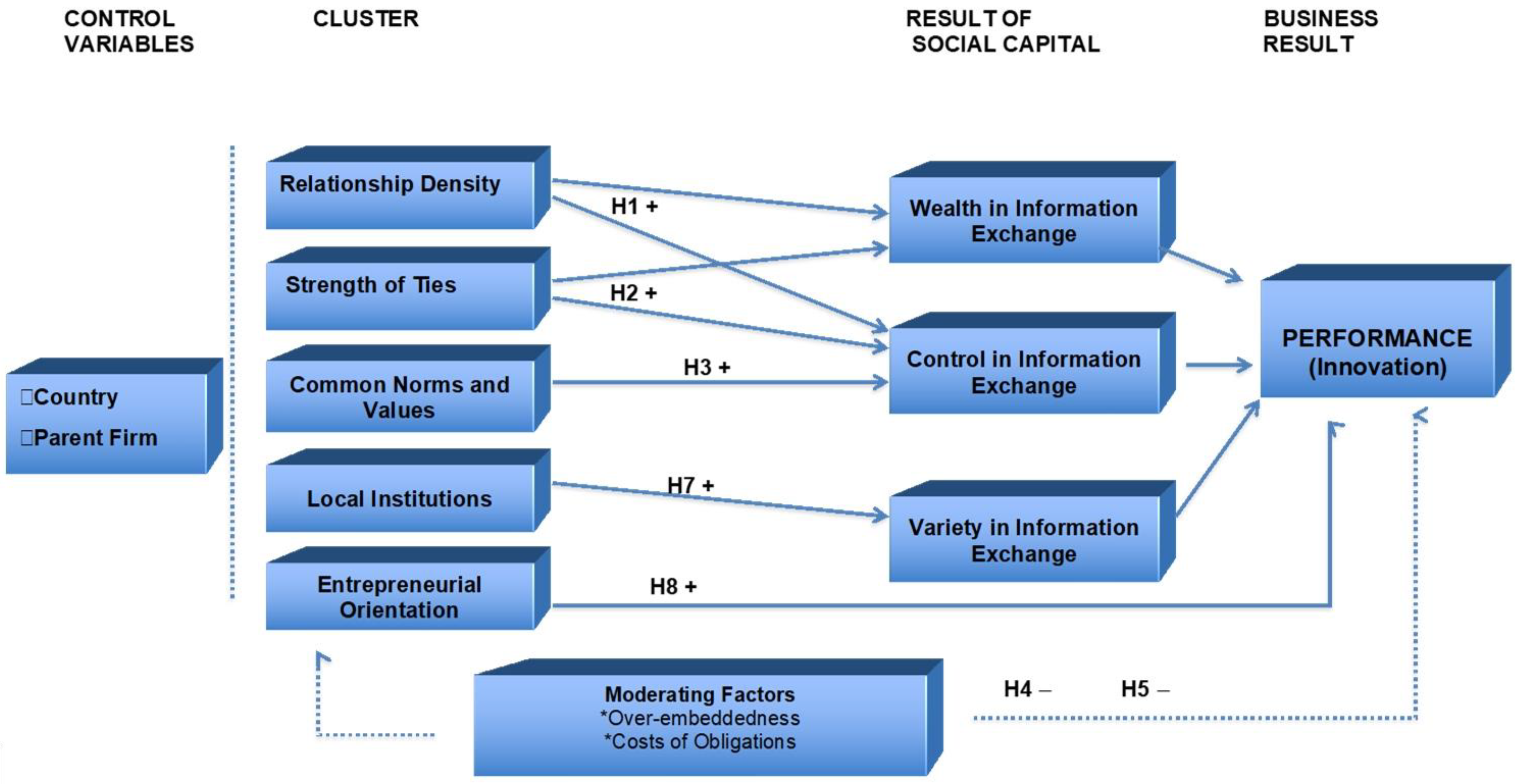

| H1 | The interrelationship between the parent firm and its spin-off in the clusters determines a dense structure and strong ties. | Not confirmed |

| H2 | The interrelationship between the parent firm and its spin-off in the clusters promotes the exchange of quality information and tacit knowledge through strong ties. | Confirmed |

| H3 | The relationships between the parent firm and its spin-off in business clusters produce norms and values that regulate the exchange of knowledge between them. | Confirmed |

| H4 | The strength of ties in the social relations between the geographically grouped parent firm and its spin-off produces a decrease in results after a certain point or level of intensity. | Not confirmed |

| H5 | Common norms and values generate obligations between the parent firm and its spin-off and produce decreasing returns after a certain point or level. | Not confirmed |

| H6 | The interrelationship of the parent firm and its spin-off produces higher levels of innovation for the parent firm than nonparent companies with other companies. | Not confirmed |

| H7 | Local institutions act as intermediaries, providing the clusters with a variety of knowledge resources that lead to higher levels of innovation in the parent firm. | Not confirmed |

| H8 | The entrepreneurial orientation of the parent firm compared with nonparent companies in business clusters produces higher levels of innovation. | Not confirmed |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cardoso, F.M.C.B.; Martínez-Fernández, M.T.; Sousa, M.d.M.; Hoffmann, V.E. The Structure and Nature of Social Capital in the Relationship between Spin-Offs and Parent Companies in Information Technology Clusters in Brazil and Spain. Economies 2024, 12, 241. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies12090241

Cardoso FMCB, Martínez-Fernández MT, Sousa MdM, Hoffmann VE. The Structure and Nature of Social Capital in the Relationship between Spin-Offs and Parent Companies in Information Technology Clusters in Brazil and Spain. Economies. 2024; 12(9):241. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies12090241

Chicago/Turabian StyleCardoso, Flávio Manoel Coelho Borges, Maria Teresa Martínez-Fernández, Marcos de Moraes Sousa, and Valmir Emil Hoffmann. 2024. "The Structure and Nature of Social Capital in the Relationship between Spin-Offs and Parent Companies in Information Technology Clusters in Brazil and Spain" Economies 12, no. 9: 241. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies12090241