External Shocks, Trade Margins, and Macroeconomic Dynamics

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. VAR Evidence

2.1. Data

2.2. VAR Specification

2.3. Results

3. The Model

3.1. Demand Block

3.2. Supply Block

3.3. Exchange Rate Regimes

4. Simulations

4.1. Calibration

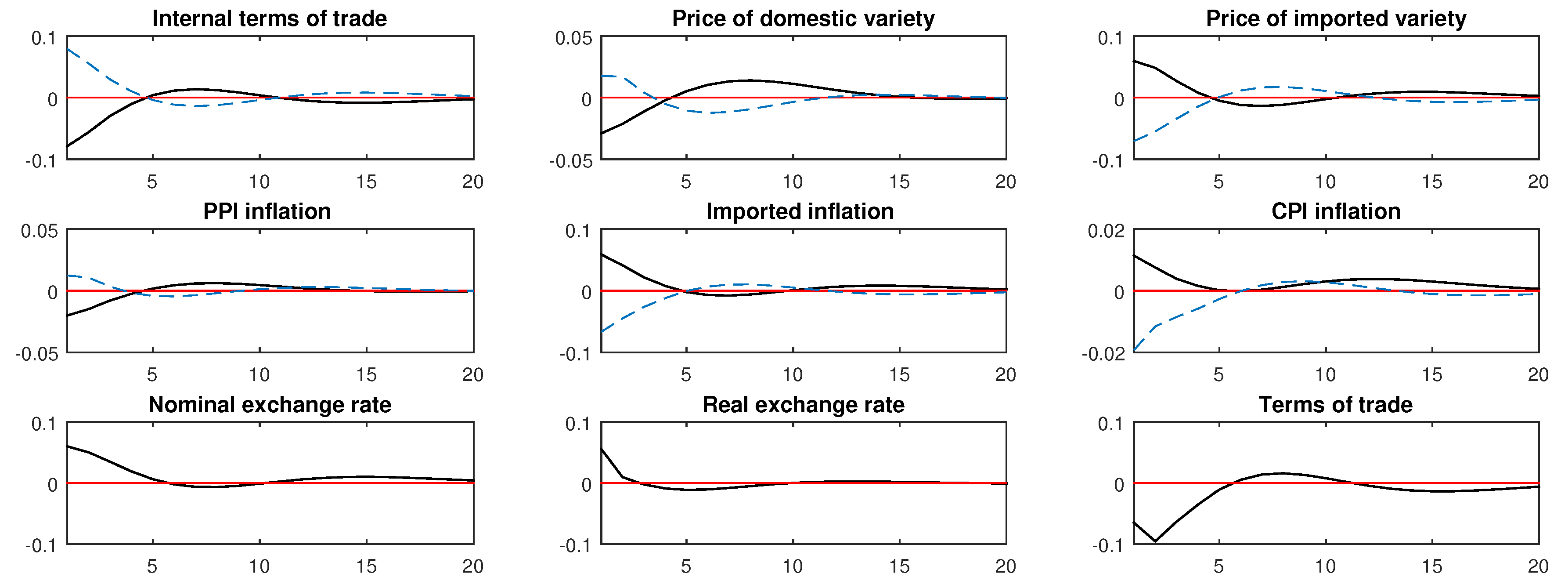

4.2. Impulse Responses

4.3. Second Moments

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix A.1. The Complete Model

Appendix A.1.1. Households

Appendix A.1.2. Firms

Appendix A.1.3. Price Setting

Appendix A.1.4. Equilibrium and Aggregate Accounting

Appendix A.2. Steady State

Appendix A.3. Loglinear Model

Appendix B

Appendix B.1. Data

| Original Series | Source | Data Transformation |

|---|---|---|

| Peggers and Floaters Nominal GDP | OECD.StatExtracts | log difference after deflating with the GDP Deflator |

| Peggers and Floaters GDP Deflator | OECD.StatExtracts | None |

| Peggers and Floaters Export Price index | IFS-IMF database | Used to calculate the terms of trade |

| Peggers and Floaters Import Price index | IFS-IMF database | Used to calculate the terms of trade |

| Peggers and Floaters Trade Margins | UN Comtrade database | none |

Appendix B.2. Peggers and Floaters

| Peggers | Floaters |

|---|---|

| Belgium | Australia |

| Denmark | Canada |

| Finland | Czech Republic |

| France | Iceland (After 2001) |

| Germany | Japan |

| Iceland Before 2001 | Mexico |

| Italy | New Zealand |

| Luxembourg | Norway |

| Netherlands | South Korea |

| Portugal | Sweden |

| Spain | Switzerland |

| United Kingdom | |

| United States |

References

- Alessandria, George, and Horag Choi. 2007. Do sunk costs of exporting matter for net export dynamics? The Quarterly Journal of Economics 122: 289–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambler, Steve, Emanuela Cardia, and Christian Zimmermann. 2004. International business cycles: What are the facts? Journal of Monetary Economics 51: 257–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Atkeson, Andrew, and Ariel Burstein. 2008. Pricing-to-market, trade costs, and international relative prices. American Economic Review 98: 1998–2031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Auray, Stéphane, Aurélien Eyquem, and Jean-Christophe Poutineau. 2012. The effect of a common currency on the volatility of the extensive margin of trade. Journal of International Money and Finance 31: 1156–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Backus, David K., Patrick J. Kehoe, and Finn E. Kydland. 1992. International real business cycles. Journal of Political Economy 100: 745–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Belke, Ansgar, Matthias Göcke, and Martin Günther. 2013. Exchange Rate Bands Of Inaction And Play-Hysteresis In German Exports—Sectoral Evidence For Some Oecd Destinations. Metroeconomica 64: 152–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Belke, Ansgar, and Dominik Kronen. 2019. Exchange rate bands of inaction and hysteresis in EU exports to the global economy: The role of uncertainty. Journal of Economic Studies 46: 335–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bergin, Paul R., and Giancarlo Corsetti. 2015. Beyond Competitive Devaluations: The Monetary Dimensions of Comparative Advantage. Cambridge Working Papers in Economics 1559, Faculty of Economics. Cambridge: University of Cambridge. [Google Scholar]

- Bergin, Paul R., and Reuven Glick. 2009. Endogenous tradability and some macroeconomic implications. Journal of Monetary Economics 56: 1086–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergin, Paul R., and Ching-Yi Lin. 2012. The dynamic effects of a currency union on trade. Journal of International Economics 87: 191–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bilbiie, Florin O., Fabio Ghironi, and Marc J. Melitz. 2007. Monetary policy and business cycles with endogenous entry and product variety. In NBER Macroeconomics Annual. Edited by Virgiliu Midrigan and Julio J. Rotemberg. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, vol. 22, pp. 299–379. [Google Scholar]

- Bilbiie, Florin O., Fabio Ghironi, and Marc J. Melitz. 2012. Endogenous entry, product variety, and business cycles. Journal of Political Economy 120: 304–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Blanchard, Olivier Jean, and Danny Quah. 1989. The Dynamic Effects of Aggregate Demand and Supply Disturbances. American Economic Review 79: 655–73. [Google Scholar]

- Born, Benjamin, Falko Juessen, and Gernot J. Muller. 2013. Exchange rate regimes and fiscal multipliers. Journal of Economic Dynamics and Control 37: 446–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cacciatore, Matteo, Giuseppe Fiori, and Fabio Ghironi. 2015. The domestic and international effects of euro area market reform. Research in Economics 69: 555–81, forthcoming. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campa, Jose Manuel, and Linda S. Goldberg. 2005. Exchange Rate Pass-Through into Import Prices. The Review of Economics and Statistics 87: 679–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavallari, Lilia. 2010. Exports and foreign direct investments in an endogenous-entry model with real and nominal uncertainty. Journal of Macroeconomics 32: 300–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavallari, Lilia. 2013a. Firms’ entry, monetary policy and the international business cycle. Journal of International Economics 91: 263–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavallari, Lilia. 2013b. A note on firm entry, markups and the business cycle. Economic Modelling 35: 528–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavallari, Lilia. 2015. Entry costs and the dynamics of business formation. Journal of Macroeconomics 44: 312–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavallari, Lilia, and Stefano D’Addona. 2015. Exchange rates as shock absorbers: The role of export margins. Research in Economics 69: 582–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavallari, Lilia, and Stefano D’Addona. 2017. Output stabilization in fixed and floating regimes: Does trade of new products matter? Economic Modelling 64: 365–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavallari, Lilia, and Stefano D’Addona. 2019. Export margins and world shocks: An empirical investigation in fixed and floating regimes. Applied Economics 2019: 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, Satyajit, and Russell Cooper. 1993. Entry and Exit, Product Variety and the Business Cycle. NBER Working Papers 4562. Cambridge: National Bureau of Economic Research, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Corsetti, Giancarlo, Philippe Martin, and Paolo Pesenti. 2013. Varieties and the transfer problem. Journal of International Economics 89: 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corsetti, Giancarlo, and Paolo Pesenti. 2005. International dimensions of optimal monetary policy. Journal of Monetary Economics 52: 281–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- de Blas, Beatriz, and Katheryn N. Russ. 2015. Understanding markups in the open economy. American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics 7: 157–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Engel, Charles, and Jian Wang. 2011. International trade in durable goods: Understanding volatility, cyclicality, and elasticities. Journal of International Economics 83: 37–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Everaert, Gerdie, and Lorenzo Pozzi. 2007. Bootstrap-based bias correction for dynamic panels. Journal of Economic Dynamics and Control 31: 1160–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fomby, Thomas, Yuki Ikeda, and Norman V. Loayza. 2013. The growth aftermath of natural disasters. Journal of Applied Econometrics 28: 412–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Galì, Jordi. 1999. Technology, employment, and the business cycle: Do technology shocks explain aggregate fluctuations? American Economic Review 89: 249–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Galì, J., Gertler S, and D. Lopez-Salido. 2001. European inflation dynamics. European Economic Review 45: 1237–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ghironi, Fabio, and Marc J. Mélitz. 2005. International trade and macroeconomic dynamics with heterogeneous firms. The Quarterly Journal of Economics 120: 865–915. [Google Scholar]

- Hummels, David, and Peter J. Klenow. 2005. The variety and quality of a nation’s exports. American Economic Review 95: 704–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- King, Robert, and Sergio Rebelo. 1999. Resuscitating real business cycles. In Handbook of Macroeconomics, 1st ed. Edited by John B. Taylor and Michael Woodford. New York: Elsevier, vol. 1, Part B, chp. 14. pp. 927–1007. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, Logan T. 2014. Exports versus multinational production under nominal uncertainty. Journal of International Economics 94: 371–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Naknoi, Kanda. 2008. Real exchange rate fluctuations, endogenous tradability and exchange rate regimes. Journal of Monetary Economics 55: 645–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naknoi, Kanda. 2015. Exchange rate volatility and fluctuations in the extensive margin of trade. Journal of Economic Dynamics and Control 52: 322–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nickell, Stephen J. 1981. Biases in Dynamic Models with Fixed Effects. Econometrica 49: 1417–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pesaran, M. Hashem, and Zhirong Zhao. 1999. Bias reduction in estimating long-run relationships from dynamic heterogeneous panels. In Analysis of Panels and Limited Dependent Variable Models. Edited by Hsiao Cheng, Pesaran M. Hashem, Lahiri Kajal and Lee Lung Fei. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 297–322. [Google Scholar]

- Rotemberg, Julio J., and Michael Woodford. 1999. Interest Rate Rules in an Estimated Sticky Price Model. In Monetary Policy Rules. Cambridge: National Bureau of Economic Research, Inc., NBER Chapters. pp. 57–126. [Google Scholar]

- Ruhl, Kim J., and Jonathan L. Willis. 2017. New exporter dynamics. International Economic Review 58: 703–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russ, Katheryn Niles. 2007. The endogeneity of the exchange rate as a determinant of fdi: A model of entry and multinational firms. Journal of International Economics 71: 344–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russ, Katheryn Niles. 2012. Exchange rate volatility and first-time entry by multinational firms. Review of World Economics 148: 269–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Taylor, John B. 1993. Discretion versus policy rules in practice. Carnegie-Rochester Conference Series on Public Policy 39: 195–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 1. | Seminal studies in this area include Atkeson and Burstein (2008); Alessandria and Choi (2007), and Ghironi and Mélitz (2005). See also, inter alia Auray et al. (2012); Cavallari (2013a); Bergin and Corsetti (2015); Cacciatore et al. (2015), and de Blas and Russ (2015). |

| 2. | |

| 3. | Exchange rate uncertainty has been extensively studied in connection with trade hysteresis (see Belke et al. (2013) and Belke and Kronen (2019)). According to those contributions, the impact of exchange rate uncertainty and thus the exchange rate regime is not just negative but non-linear due to firm entry and exit decisions. |

| 4. | Flexible exchange rates induce production shifts in and out of the export sector that help explain the positive correlation between the relative prices of traded and non-traded goods observed in the data (Naknoi 2008). In a setup where all goods are traded, Bergin and Corsetti (2015) show that monetary stabilization under free floating can induce relocations toward sectors producing differentiated goods. |

| 5. | Early studies have documented a positive relation between a country’s extensive margin of exports and its terms of trade (Cavallari and D’Addona 2015), and a positive relation with external demand shocks (Cavallari and D’Addona 2017). |

| 6. | More general assumptions about the structure of export costs can generate a richer (and more realistic) export dynamics, as in Ruhl and Willis (2017). |

| 7. | In an empirical contribution Cavallari and D’Addona (2019) extended the analysis to 2018, investigating the role of the great trade collapse occurred in 2008–2009. |

| 8. | |

| 9. | |

| 10. | The exogenous VAR model is estimated over the period 1970–2011 for efficiency reasons. |

| 11. | We refer to Cavallari and D’Addona (2017) for an extensive discussion of the reasons for adopting a dichotomous classification with country-pair data. |

| 12. | Results provided in this section were further scrutinized with an extensive robustness check on the (i) lag structure, (ii) parameter restrictions (iii) sample selection. Results, available upon request, are qualitatively the same under all the tested specifications. |

| 13. | The nominal exchange rate is defined as units of home currency per one unit of foreign currency. The real exchange rate is defined as An increase in both q and is therefore a depreciation. The home terms of trade are the price of home exports relative to the price of home imports . |

| 14. | With symmetric demand elasticity, the optimal strategy is to set prices in the producers’ currency and let the final price vary with exchange rate at a constant rate (Corsetti and Pesenti 2005). |

| 15. | |

| 16. | |

| 17. | We refer to Cavallari and D’Addona (2015) for details about the derivation. |

| 18. | The shape parameter is such that where is the average standard deviation of the extensive margin in our sample. |

| 19. | A natural extension is to consider multi-sector models with entry in both homogeneous and differentiated goods sectors. This is beyond the scope of this paper. |

| 20. | Investments and entry variables behave similarly in the data (Chatterjee and Cooper 1993). For a recent assessment of the cyclical properties of business formation, see Cavallari (2015). |

| 21. | Backus et al. (1992) find cross-correlations of output and consumption between US and Europe, respectively, 0.66 and 0.51. In a large sample of developed economies, Ambler et al. (2004) document even smaller cross-country comovements. |

| 22. | In a sample of European data, Auray et al. (2012) document a rise in the extensive margin of exports of intra-EMU trade as large as 21% after European monetary unification. |

| 5 year/Long Run Response of Vbl. in Column to A Positive Shock | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Productivity | GDP | Inflation | Energy Price | FFR | |

| TFP shock | + | + | - | - | no restr |

| AD shock | 0 | + | + | + | no restr |

| FFR shock | 0 | 0 | - | no restr | no restr |

| Panel A: home Variables | |||

| stand. dev. (Ratio to Y) | corr. with Y | Auto-Correlation | |

| C | 0.92 | 0.95 | 0.73 |

| L | 1.46 | 0.46 | 0.71 |

| 4.05 | 0.59 | 0.88 | |

| Panel B: cross-correlation | |||

| Y | C | ||

| 0.42 | – | – | |

| – | 0.97 | – | |

| – | – | −0.98 | |

| Panel C: trade variables | |||

| 1.26 | 0.52 | 0.67 | |

| 1.28 | −0.53 | 0.67 | |

| Net exports | 0.52 | −0.51 | 0.73 |

| Floaters | Peggers | |

|---|---|---|

| Panel A: Standard deviation | ||

| Y | 0.81 | 1.74 |

| C | 0.75 | 1.03 |

| L | 1.18 | 3.34 |

| 3.28 | 9.42 | |

| 1.26 | 2.18 | |

| 1.28 | 2.3 | |

| 1.91 | 3.57 | |

| 1.35 | 2.55 | |

| 0.15 | 0.19 | |

| 0.36 | 0.29 | |

| Panel B: Standard deviation relative to Y | ||

| C | 0.92 | 0.59 |

| L | 1.46 | 1.92 |

| 4.05 | 5.41 | |

| 1.56 | 1.25 | |

| 1.58 | 1.26 | |

| 2.35 | 2.05 | |

| 1.67 | 1.47 | |

| 0.19 | 0.11 | |

| 0.44 | 0.17 | |

| Panel C: Correlation with Y | ||

| C | 0.95 | 0.88 |

| L | 0.46 | −0.66 |

| 0.59 | −0.62 | |

| 0.52 | 0.9 | |

| −0.53 | −0.9 | |

| 0.33 | −0.81 | |

| 0.82 | 0.47 | |

| 0.19 | −0.83 | |

| −0.21 | 0.57 | |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

D’Addona, S.; Cavallari, L. External Shocks, Trade Margins, and Macroeconomic Dynamics. Economies 2020, 8, 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies8010006

D’Addona S, Cavallari L. External Shocks, Trade Margins, and Macroeconomic Dynamics. Economies. 2020; 8(1):6. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies8010006

Chicago/Turabian StyleD’Addona, Stefano, and Lilia Cavallari. 2020. "External Shocks, Trade Margins, and Macroeconomic Dynamics" Economies 8, no. 1: 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies8010006

APA StyleD’Addona, S., & Cavallari, L. (2020). External Shocks, Trade Margins, and Macroeconomic Dynamics. Economies, 8(1), 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies8010006