1. Introduction

The increase in residential areas that lack basic infrastructure and services, houses constructed on land without security of tenure and proper building plan (informal settlements) have been a challenge for governments of most countries (

UN-Habitat 2015b;

Brown 2015). Some of the characteristics of informal settlements include the presence of mainly temporary houses such as makeshift houses which deviate from standard building regulations and presence of low-income earners or unemployed, which renders them incapable of been able to rent a house (

Abunyewah et al. 2018;

Hofmann et al. 2008). As residents of informal settlements often face the risk of eviction or relocation to other areas they tend to prefer constructing makeshift houses (

Khalifa 2015). It is important to note that some residents of informal settlements may construct permanent houses after living in the same area for several years. The factors that contribute to the increase in informal settlements include population growth, rural–urban migration, inadequate affordable housing, weak planning and urban management, displacement caused by conflict, natural disaster and climate (

UN-Habitat 2015b).

Informal settlements are often geographically, economically, socially and politically disengaged from the wider urban systems. However, the attitude of governments to informal settlements has been either opposition and eviction or reluctant tolerance for upgrading it (

UN-Habitat 2015a). The upgrade of an informal settlement has been a widely accepted solution compared to eviction and relocation of residents of the settlement (

Khalil et al. 2016;

Mardeusz 2014). This often involves land tenure regularization and provision of basic infrastructure (

Devas et al. 2004). In order to address the adverse impact of informal settlements on the well-being of residents and the area hosting the settlements, there is a need for governments to be well-informed of the issues associated with it. This will assist the government in developing mechanisms for integrating settlements into the urban area system. One potential way of doing it is to upgrade informal settlements so that it can be at par with formal areas and to provide an effective mechanism that can be used to restrict the emergence of new informal settlements. Upgrading an informal settlement has the potential to assist residents to sustain their social and economic networks which is necessary for their livelihoods. The goal of the upgrade is often to achieve settlement security, basic sanitation and good road networks (

Marais et al. 2018). It is an intervention which is often used to rebuild collective socio-economic strength among informal settlement residents and long-term settlement security (

Dhabhalabutr 2016). Upgrading an informal settlement involves the transformation of various dimensions of the settlement such as economic, social, organization and environment (

Dhabhalabutr 2016).

For a settlement upgrade to be successful, the process of the upgrade should be undertaken in collaboration with key stakeholders such as local authorities and community groups from affected communities (

Nassar and Elsayed 2018). Residents of the informal settlements to be upgraded should be well-informed about the proposed upgrade especially its benefits and costs, before commencing the upgrade. As informal settlements often have restricted access to facilities such as a market, it has the potential to increase the barriers that women face in accessing livelihood opportunities (

Chant 2014). For instance, women who reside in the informal settlements have the tendency to use more time to access basic services compared to those in formal settlements (

UNFPA 2007). Furthermore, poor quality housing, eviction and homelessness have the potential to raise the risk of insecurity and violence against women and other vulnerable groups (

McIlwaine 2013).

Upgrading an informal settlement provides basic infrastructure and services which can improve quality of life of residents (

Wakesa et al. 2011). However, it is important to consider the impact that the upgrade can have on low-income households (

Lees et al. 2016). The upgrade has the potential to increase land prices and house prices which may contribute to restricted access to affordable housing to these households. Housing is one of the necessities, which is strongly linked to economic development of a country. It has the potential to trigger the growth of several sectors of the economy. However, housing is becoming a luxury good for some residents of cities in developing countries. For instance, in a study of affordability of house rent,

Ezebilo (

2017) found that housing has become a luxury for residents of Port Moresby, the capital of Papua New Guinea (PNG). This is because the supply of houses has not been able to match with the demand for it, which pushed house prices up beyond the price that most households can afford. The housing affordability problem often compel some households to move to informal settlements where they can find houses they can afford (

Ezebilo and Thomas 2019).

As some of the informal settlements are located in areas that lack all or some basic social infrastructure such as piped-borne water and sewerage, good road networks and electricity, it lowers residents’ welfare and opportunities for a more decent life. Further, government loses revenue that would have accrued to it via building permits and service charges from the use of public utilities (

Fernandes 2011). The benefit that would have accrued to property developers is not maximized because of lack of infrastructure and services. In order for an informal settlement upgrade to be sustainable, there is a need to understand the socio-economic dynamics of residents and their willingness to accept the proposed changes associated with the upgrade. This study contributes to it by generating information from the residents and their leaders on the current situation of the settlements and the desired changes required as well as the nature of households that inhabit informal settlements.

Government agencies that have the responsibility to implement upgrade of informal settlements often face the challenge of implementing the upgrade in an orderly manner because of lack of appropriate guidelines (

Nassar and Elsayed 2018;

Del Mistro and Hensher 2009). Without proper guidelines, the upgrade may not be sustainable and it may result in conflict of interests, lack of support from key stakeholders and loss of public funds. This study contributes to developing appropriate guidelines that can be applied in the upgrade of an informal settlement in urban areas in PNG. It can provide lessons that urban development planners from cities in other developing countries can draw from.

Using Port Moresby as a case, the objectives of this study are the following:

To examine informal settlement residents’ preferences for infrastructure and services and to identify factors influencing their decision to live in a makeshift house.

To examine informal settlement residents’ perceptions of how an upgrade project should be implemented.

Findings from this study have the potential to assist municipal authorities, planners and urban development managers in upgrading informal settlements in an orderly manner. The findings also have the potential to contribute to the development of guidelines for informal settlement upgrade and in the choice of infrastructure and services to be provided in various informal settlements.

2. Literature on Status and Upgrade of Informal Settlements

Several papers which focus on the status of informal settlements and potential ways to address issues associated with settlements have been published by several authors. In an Indonesian study of status of informal settlements in Jakarta,

Alzamil (

2018) found that upgrading the settlements should be according to a comprehensive plan that includes priority improvements. Local communities should be involved in the upgrade of informal settlements because they have information of the most felt needs in the settlements. In a PNG study of assessment of Joyce Bay settlement in Port Moresby,

ADB (

2013) found that there is deteriorating living conditions in the settlement as a result of social exclusion, inadequate basic services, economic barriers and increasing inequality. There is a need to implement interventions to improve living conditions of the communities. In a Mexican study of the spatial, social and cultural construction of place in the context of informal settlements in Mexico,

Lombard (

2014) found that a focus on residents on place-making activities hints at the prospects for rethinking informal settlements.

Other papers include an Egyptian study of government responses to the informal settlement expansion in greater Cairo,

El-Batran and Arandel (

1998) found that informal settlement is a dominant factor in the urbanization process and in the provision of housing for the urban poor. Settlements should not be seen as part of a country’s housing crisis but rather the urban poor’s contribution to its solution. In another Egyptian study of informal settlements,

Hassan (

2012) found that the traditional approaches of mainstream for the development of informal settlements is inadequate towards solving the social and economic problems in the settlements. Urban regeneration has the potential to address issues associated with informal settlements in Alexandria, Egypt. In a Chinese study of informal settlement residents’ satisfaction,

Li and Wu (

2013) found that local context is the main determinant of satisfaction. In Egypt, an urban upgrade project was used to upgrade El-Arab with the main aim of developing the physical and economic conditions of the area (

Khalil et al. 2016). The upgrade focused on physical, waste management and urban agriculture. In a comparative study of Egyptian and Indian informal settlements,

Ragheb et al. (

2016) found that in order to make the upgrade of informal settlement successful, local culture in the settlement should be considered. Opportunities to continue intergenerational lifestyles and businesses should be provided.

Demolishing informal settlements does not help to build a harmonious society. In a study of urban planning and informal cities in southeast Europe,

Tsenkova (

2012) found that the formalization of informal settlements in Serbia, Croatia and Albania emphasizes the integration of informal land and housing into formal economy and validation of ownership through property titles. Responses to formalization of an informal settlement vary according to local contexts, type of settlement, government’s political orientations and pressure from target communities.

In a South African study of the socio-economic characteristics of informal settlement residents,

Hunter and Posel (

2012) found that government policy on informal settlements reflects a tension between two approaches that recognizes the legitimacy of informal settlements and the removal of settlements. Upgrading informal settlements through in situ-development has the potential to make the process successful. In another South African study on informal settlement upgrade,

Patel (

2013) found that successful outcomes are strongly linked to the manner in which the upgrade process is implemented. Formal changes that result in successful outcomes are achieved by the continued and consolidated power and influence of the local communities. Following the end of apartheid in South Africa in 1994, South African Government embarked on the upgrade of informal settlements (

Mardeusz 2014). This was accomplished using the Reconstruction and Development Program and the Breaking New Ground program. The implementation of the program transformed informal settlements into formal settlements especially in Cape Town. However, the programs were not able to match the rapid demand for housing. The upgrade was not able to address the high level of crime, poverty and unemployment in the transformed informal settlements (

Myers 2011).

In an Afghan study of policies to address and improve informal settlements,

Collier et al. (

2018) found that the process of upgrading settlements should be simple, cheap and have quick results. Visible improvements have the potential to generate support from local communities in short run, which can build support for longer-term reform. In Thailand, the upgrade of informal settlements is believed to be the solution to housing problem (

Dhabhalabutr 2016). This has resulted in the continuous upgrade of several informal settlements by the Thai Government, non-governmental organizations (NGOs) and international agencies. An example of a popular informal settlement upgrade program in Thailand is the Baan Mankong (BMK) that was applied in the upgrade of several informal settlements in Bangkok. In Nigeria, the government upgraded several informal settlements with the aim of increasing the quantity of formal housing and improving the quality of urban housing especially in the latter half of the 20th century (

Ibem 2011). Apart from the upgrade of informal settlements, Nigerian Government implemented initiatives that focused on the construction of subsidized housing units for low-income households. However, the initiative was not effective in reducing informal settlements as a result of mismanagement of resources. For instance, funds meant for the construction of 200,000 housing units was released by the government, only 25 percent of the units was completed (

Ibem 2011).

It is important to note that informal settlement upgrade is often an attempt by the government to reduce issues associated with access to land that restricts a country from achieving development in a sustainable manner (

Potsiou et al. 2019). The inadequate or lack of social infrastructure and services in informal settlements tend to restrict residents from achieving their full potential. It contributes to the loss of government revenue as a result of several informal activities in the settlements in which beneficiaries do not pay tax (

Fernandes 2011). For instance, some informal settlements are known to be accessing services such as water and electricity through unauthorized connections. Thus, they evade service charges and as a result, government loses revenue. This tends to have adverse impacts on a country’s economy. The upgrade of an informal settlement has the potential to address these externalities created by the inadequacies associated with the area.

In Asia Pacific, only a few published papers have focused on the upgrade of informal settlements such as

Watt (

2020), who found in a Fijian study of the effect of providing electricity in informal settlement on residents that residents are often excited of the news but some either move to settlements that have not been upgraded or try to subvert the infrastructure. In an Indonesian study of how informal settlements have been positioned via upgrading policies in city urbanization plan,

Jones (

2017) found that a shift from slum upgrade to vertical towers which appear incompatible in accommodating the way of practiced in the informal settlement may be resisted. He suggested that there should be leadership and political commitment and recognition of contextual response when developing informal settlement upgrading policies and strategies.

Yap (

2016) concluded that the housing problems of urban low-income population can only be solved when the urban poor have access to urban land. However, urban planning and government interventions in the urban land market are required.

The upgrade of an informal settlement is often implemented as a poverty alleviation project (

Magalhaes and Eduardo 2005). It is often expected that the project will contribute toward increasing the physical capital of residents of informal settlements as a result of the regularization of land tenure and the increase in land value triggered by the infrastructure and services brought in to the informal settlement. The increase in human capital in the informal settlement as a result of an upgrade often contributes to an improvement in well-being and educational level of residents and an increase in job opportunities for them (

Marais et al. 2018). The upgrade project has the potential to enhance the settlements’ social capital as a result of public participation in the design and implementation of the project (

Magalhaes and Eduardo 2005).

It is important to note that addressing the problems associated with informal settlements in PNG cities such as Port Moresby might generate additional problems such as housing affordability problems especially for low-income households who live in informal settlements. However, it will also provide more benefits to residents and the municipal authorities. The new issues that may emerge include the need for a more integrated and broad-based upgrade intervention processes. There is a need to consider interventions that can be used to address issues associated with public transport, traffic, road and intersection improvements and urban services of paramount importance in the city especially in high-density and high-use areas.

The implementation of informal settlement upgrade project is likely to be more complex and challenging in densely-populated areas than sparse areas. The densely-populated areas would attract more transaction costs through resettlement of some residents that occupy areas where trunk infrastructure such as piped-borne water, sewerage, electricity and good road networks will be constructed. This will require negotiation and compensation especially in PNG where most land is communally-owned (

Wangi and Ezebilo 2017). Thus, the upgrade may attract a lot of unexpected costs both for infrastructure and space where it will be constructed. Time is also needed for negotiation between municipal authorities and landowners.

The informal settlement upgrade project will attract costs for infrastructure and time required for negotiations with landowners. However, it has the potential to provide opportunities for the development of the underdeveloped segment of Port Moresby, which can increase the share of formal business activities in the city.

The integration of informal settlements to the entire structure of Port Moresby can generate social benefits to entire neighborhoods of the city and will contribute to the removal of negative externalities brought by the settlements. The benefits include the construction of roads connecting the informal settlements to nearby neighborhoods and the construction of other infrastructure.

As there is no simple solution to informal settlement, the problem is strongly linked to national economic wealth and the level of social and economic capital (

Potsiou et al. 2019). Solutions to informal settlement are a function of consistent land policies, good governance and well-established institutions and systems. There is a need for guidelines to address issues that result in informal settlement development in urban areas.

4. Results

All the people who were selected for the interviews agreed to be interviewed, which indicate that they are interested in the subject of the study.

4.1. Socio-Economic Characteristics of Residents

In terms of occupation, most of the interviewees were unemployed (64.6%) and only a few were self-employed (4.6%). See

Table 1.

Most of them had secondary school (36.6%) as their highest educational level, followed by technical school and none had university education. Only a few of the interviewees (24.7%) had access to electricity supplied by PNG Power and only 2 percent had access to garbage collection services. Only 2 percent had access to piped-borne potable water supplied by Eda Ranu (currently known as Water PNG) in a central location (

Table 1). Majority of the residents buy water from water vendors and store it in large containers.

The findings show that more of the interviewees lived in houses built on State-owned land (68.6%) than on customarily-owned land (

Table 1). On average, household income from informal activities account for approximately 73 percent of the total annual household income. The interviewees had an average family size of five persons and most of them were married and had an average age of 38 years.

In terms of the distribution of annual household income, interviewees who lived in permanent houses had more income than those who lived in makeshift houses (

Figure 1). More of the interviewees that had income of less than PGK12,500 and from PGK12,500 to PGK19,999 lived in makeshift houses (32%) than those who lived in permanent houses (5.8%).

More of the interviewees who lived in permanent houses had income that ranges from PGK20,000 to PGK250,000 and above (61.4%) than those who lived in makeshift houses (44.4%). See

Figure 1.

Of all the four regions in PNG, Southern Region had the highest number of ordinary residents who lived in permanent houses (42.2%). See

Figure 2. Highlands Region had the highest number of ordinary residents who lived in makeshift houses (41.9%).

Only a few of the interviewees who lived in makeshift houses belonged to New Guinea Islands (5.8%). It was also a few interviewees who belonged to New Guinea Islands that lived in permanent houses (10.1%)—

Figure 2.

In terms of the distribution of income in relation to the type of land that the interviewee occupied, the income of the interviewees who occupied customary land was generally higher than those who occupied State land (

Figure 3). Most of the interviewees whose income was less than PGK12,500 (3.2%) and between PGK20,000 to PGK32,999 (28%) occupied State land.

For interviewees who had income of PGK250,000 and above, there is no difference between those who occupied State land (1.6%) and customary land (1.7%).

In terms of the type of land occupied by the interviewees in relation to the region they belonged,

Southern Region had the highest occupant of customary land (54.8%) whereas Highlands Region had the highest occupant of State land (40.6%)—see

Figure 4. New Guinea Islands had the lowest occupants of both customary and State land (8.1% and 8.3% respectively).

4.2. Residents’ Decision to Live in a Makeshift House

Of all the 195 ordinary resident interviewees, 167 (85.6%) answered all the questions that were relevant for inferential statistical analysis. Thus, 167 observations were used for statistical analysis.

The results revealed that of all the interviewees, 45 percent lived in makeshift houses (i.e., temporary shelter) and 55 percent lived in permanent houses (

Table 2). On average, their households earned a total income (informal and formal income) of PGK54,497. Most of the interviewees owned a house in informal settlements (82%) and only a few (18%) lived in rented houses. The results showed that most of the interviewees lived in a neighborhood where there is frequent crime (80%).

Forty-one percent of the interviewees were female and 51 percent were male. More of them lived on State land (69%) than customary land (31%). Most of the interviewees lived in houses where toilets are shared by different families and have lived in informal settlements for an average of 13.3 years (

Table 2).

In order to understand factors influencing interview’s decision to live in a makeshift house, binary logit regression models were estimated (

Table 3). The log likelihood test is highly statistically significant, which indicates that the estimated model has an acceptable goodness of fit. Further, more than 80 percent of the interviewees were correctly predicted to be in the group to which they actually belonged. This reveals that the binary logit model displays a good fit. Using the marginal effect to rank the importance of coefficients, the most important coefficients are those associated with house ownership, frequency of crime in the neighborhood, occupation and land tenure type.

The coefficients associated with house ownership, frequency of crime in the neighborhood and the sharing of toilet by different families were positive and statistically significant. This indicates that interviewees who own a house in informal settlement, experience crime frequently where they live and lived in a house where toilet is shared by different families were willing to live in makeshift houses. Coefficients associated with land tenure type, household size, occupation and number of years lived in informal settlement were negative and statistically significant (

Table 3). This indicates that interviewees who occupied State land, have large household size, work for the government and have lived in informal settlement for many years were not likely to live in makeshift houses.

Coefficient associated with income had expected sign but was not statistically significant. Coefficient associated with gender was not also significant. In terms of marginal effect, interviewees who owned a house in informal settlement lived in the neighborhood where crime is frequent and lived in a house where different families use the same toilet were 56 percent, 51 percent and 22 percent more willing to live in a makeshift house. Interviewees who occupied State land, have many persons in the household, worked for government and have lived in informal settlement for many years were 38 percent, 3 percent, 39 percent and 3 percent less likely to live in makeshift houses, respectively.

4.3. Most Important Infrastructure and Services as Perceived by Residents

The results revealed that almost all the interviewees (97.4%) reported that potable-piped water supplied by Eda Ranu (now Water PNG) is the most important infrastructure needed in the informal settlements where they lived (

Figure 5). Only a few of the interviewees reported that sewerage and good paved road networks are the most important infrastructure (1.5% and 1.02% respectively).

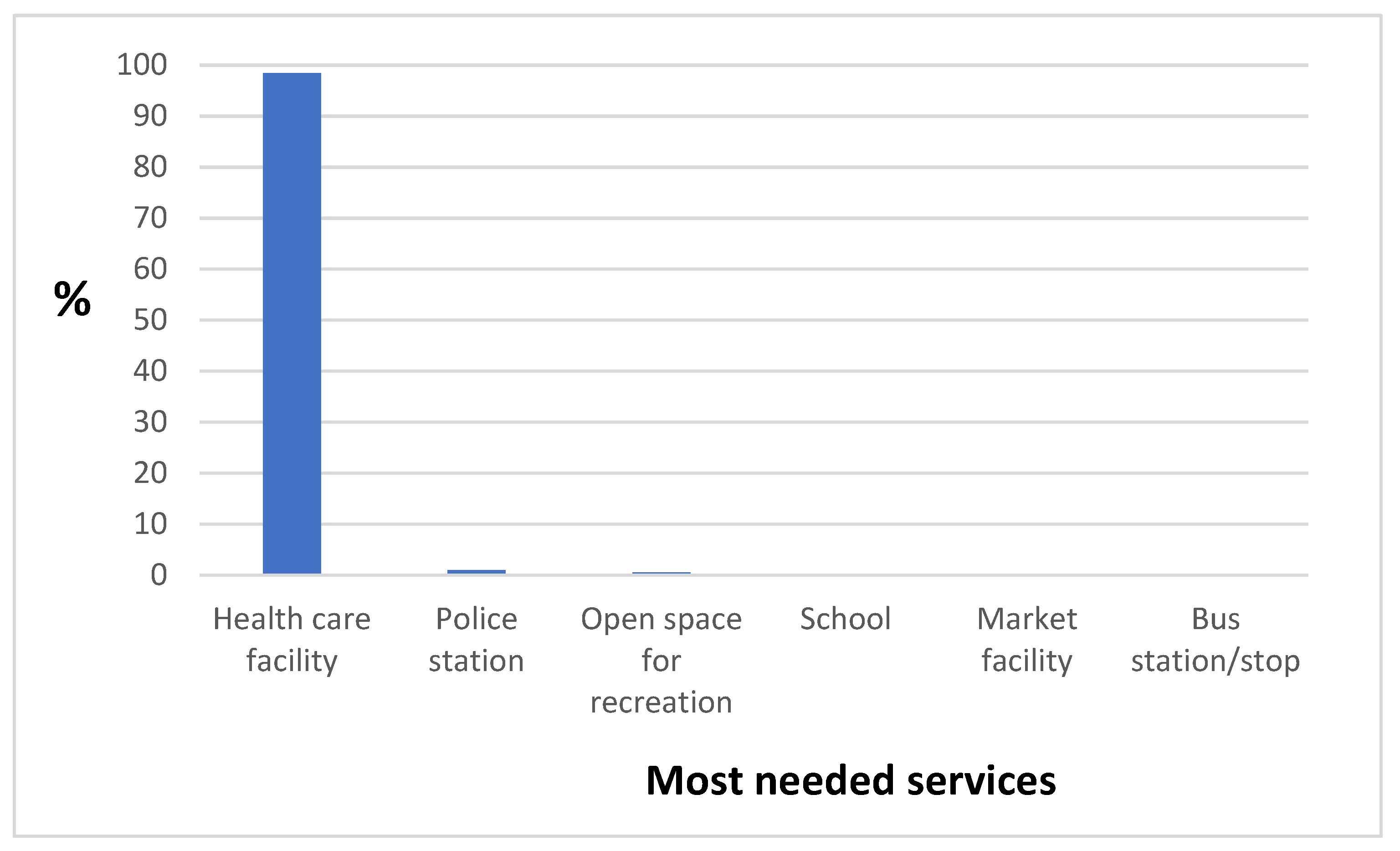

None of the interviewees reported that electricity supplied by PNG Power is of most importance. In terms of the most important services needed in the informal settlement, almost all the resident interviewees (98.4%) reported that health care facility is the most important where they lived (

Figure 6). Only a few of the interviewees reported that police station and open space for recreation are the most important (1.02% and 0.51%) respectively.

All the interviewees did not believe that schools, market facility and bus station/stop are of importance where they lived (

Figure 6).

In terms of whether informal settlement residents would bear costs associated with upgrading the area where they lived, the results revealed that all the interviewees who “owned land” in the area would pay for land registration and ground rent. They would also pay for permit for building plan.

All interviewees who are renting a house in informal settlements reported that they would pay any additional house rent as a result of the upgrade of the areas where they lived. All the interviewees would pay service charges for infrastructure and services associated with the upgrade of informal settlements where they lived.

Almost all the interviewees (96.4%) had 100 percent certainty level that they would pay for service charges following the upgrade of the informal settlements where they lived. Only a few of the interviewees (2.6%) had 50 percent certainty level whereas 1.03 percent had certainty level of 75 percent and 0.52 percent had the certainty level of less than 15 percent. This indicates that on average, informal settlement residents are more likely to pay service charges for infrastructure and services following the upgrade of the informal settlements where they lived.

4.4. Community Leaders in Relation to Group They Belonged and Their Characteristics

All the community leaders who were approached for interviews agreed to be interviewed. In total, 36 leaders were interviewed of which Church leaders had the highest number of interviewees (33.3%). Village Court, women in business and block committee had the lowest—all at 2.8 percent (

Figure 7).

Most of the community leaders belonged to Southern Region (44%), followed by Highlands Region (39%) and none is from New Guinea Islands (

Figure 8).

The results revealed that of all the leaders, there were more men (58%) than women and they have an average age of 39.7 years (

Table 4). On average, the leaders have lived in informal settlements for 40 years and have served as leaders for 10 years. Most of the leaders had high school as their highest education attainment (50%) followed by secondary school (25%). Most of the leaders were married (75%), only a few were single (

Table 4).

4.5. How Informal Settlements Upgrade Program Should Be Implemented as Perceived by Community Leaders

In terms of how informal settlement upgrade program should be implemented for it to work well, the results from QCA that originated from interviews with community leaders revealed the following:

Almost 60 percent of the community leaders that were interviewed reported that for the upgrade project to work well, informal settlement residents must be involved in planning the project. Some of the residents must be employed, especially the youths, in the upgrade program during the implementation phase:

For the upgrade program to work, residents must be involved in the program and engaged in the implementation phase of the program.

Implement the upgrade program in collaboration with residents to understand their needs and engage youths to work in the program.

More than 10 percent of the community leaders reported that proper awareness on the upgrade program, especially in terms of its benefits, costs and how it will be implemented, should be conducted in the informal settlements. The awareness will encourage residents to support the program:

First create awareness about the upgrade program throughout the informal settlements so that everyone can understand the program, especially how it will be implemented.

Discuss with residents to seek their support because several survey works have been conducted in some of the informal settlements in the past and we were promised development but to date nothing has been implemented.

More than 10 percent of the community leaders reported that there is a need to develop criteria that can be used to identify residents that are qualified for issuance of land titles and procedures for registration of land and providing infrastructure:

Give land titles to people who built houses in informal settlements and have lived there for more than five years.

The informal settlement upgrade program must be carried out in orderly manner by developing procedures in collaboration with community leaders.

The most preferred infrastructure and services should be established first to engender support from residents before establishing less preferred infrastructure and services:

Improve road conditions to facilitate the development of other infrastructure. Access road will pave way for piped water, sewerage and electricity.

Piped-potable water supplied by Eda Ranu (now Water PNG) and electricity connected by PNG Power and health care facility should be established in the informal settlements first before other infrastructure and services.

4.6. Guidelines for the Upgrade of Informal Settlements

Guidelines for upgrading informal settlements in Port Moresby as perceived by residents are the following:

Create awareness about the informal settlements upgrade project in the targeted settlements.

Discuss with community leaders about the upgrade project and seek their advice.

Conduct research to identify the most preferred infrastructure and service in each of the informal settlements to be upgraded.

Plan the implementation of the upgrade project in collaboration with key stakeholders include informal settlement community leaders.

Develop procedures, monitoring and evaluation mechanisms for the upgrade project.

Identity competent informal settlement residents and engage them in the implementation of upgrade project.

Improve road conditions to facilitate the development of other infrastructures.

Develop mechanism for identifying residents to be given state lease (for state-owned land) and genuine landowner for the case of customary land.

Provide land titles to residents who meet requirements that have been agreed on by key stakeholders.

Construct the most preferred infrastructure and services by the residents.

Monitor the upgrade project and use information from feedback to improve the project.

Provide information to residents on how to file application for building permit and payment of service charge for infrastructure that have been provided.

Conduct evaluation of the upgrade project.

5. Discussion

The findings from this study revealed that ordinary residents and community leaders of informal settlements of Port Moresby would support an upgrade project of the areas. However, for the project to be sustainable, the residents of informal settlements should be involved in the project, which should reflect their interests. Appropriate guidelines for the implementation of the project should be established. Informal settlement residents are better placed to have information on how the upgrade project can be implemented in a sustainable manner. Our findings are in line with that of

Alzamil (

2018), who found in an Indonesian study of the status of informal settlements in Jakarta, that in upgrading the settlements, the local communities should be involved. Our findings are also in line with that of

Ragheb et al. (

2016), who found in a comparative Egyptian and Indian study that an informal settlement upgrade project would be successful if local cultures there are preserved, and the opportunities of intergenerational lifestyles and businesses are provided. This suggests that in the course of implementing a settlement upgrade project, the residents of the areas should be involved in the planning and implementing, in collaboration with key government agencies that have been given the responsibility to implement the upgrade.

Piped-borne potable water supplied by Water PNG and healthcare facility is the most important facilities for the informal settlement residents. The importance they attached to potable water and health care facilities indicate that these are the most-felt needs in the informal settlement. It suggests that the informal settlement upgrade project will be more acceptable by the residents if their immediate needs (water and health care) are provided first. Our findings conform to that of

Patel (

2013) who found in a South African study on informal settlement upgrade that successful outcomes are linked to the influence of the local communities.

Alzamil (

2018) found in an Indonesian study that a settlement upgrade should follow a comprehensive plan that includes priority improvements. Thus, for the upgrade project to be successful, it is important to conduct need assessments so that the immediate needs of the residents can be identified before implementing the project. This has the potential to minimize the tendency of conflict of interests between residents and upgrade implementing agencies.

In addition to the most preferred infrastructure and services, community leaders suggested the need to also construct good road networks where it is needed first to provide space for moving in other infrastructures. This is important because it is often difficult to establish main water pipes and electric poles without road access to the areas. Thus, when it comes to the upgrade of informal settlements, accessibility matters. If the settlements are not accessible, it will be extremely difficult to deliver infrastructure and services. This suggests that, if the intention is to upgrade informal settlements in Port Moresby, key government agencies such as NCDC, Department of Works and DLPP should consider providing access road first to the settlements. The road networks will assist the agencies in the movement of materials for the construction of health care facilities and moving in pipes and other material needed for piped-borne potable water.

We found that the upgrade implementing agency has a lot to gain from the consultation with residents of informal settlements. There is a need for the agency to plan the implementation of the upgrade project properly in collaboration with key stakeholders. Effective and efficient feedback mechanisms should be included in the implementation of the project. Our findings are in line with the guidelines for the formalization of informal construction by

Potsiou et al. (

2019). If the intention is to upgrade informal settlements successfully, there is a need to implement the upgrade in an orderly manner. The implementing agency should consider adopting the guidelines developed by

Potsiou et al. (

2019) and adapt it to PNG conditions. The guidelines should include a strategy, framework preparation and upgrade implementation phases. This has the potential of making the upgrade meeting internationally acceptable standards. The agency should note that the nature of the upgrade project depends on the local contexts of the informal settlement being upgraded as reported by

Tsenkova (

2012). Thus, the nature of implementation of the project should be based on a case-by-case basis, which implies that it must be planned thoroughly.

Lessons drawn from each of the upgrade project will play an important role in implementing other projects. This calls for the evaluation of completed upgrade project and lessons identified. It is important for the upgrade process to be simple, cheap and provide quick results as suggested by

Collier et al. (

2018). Furthermore, the upgrade program should include a mechanism that can be used to restrict the emergence of new informal settlements. For instance, offenders can be asked for penalty in the form of huge fines while people who discourage the emergence of informal settlements by reporting activities of offenders to appropriate authorities are rewarded.

Land ownership and tenure often generate a conflict situation in an informal settlement upgrade project, especially in terms of making land available for constructing infrastructure. For the project to work well there is a need for the regularization of land tenure as reported by

Devas et al. (

2004). This can increase land prices and consequently increase house prices (

Lees et al. 2016). In our study, we found that almost 70 percent of the informal residents that were interviewed lived in houses constructed on State-owned land.

If the intention is to regularize their occupancy, there is a need to develop guidelines or criteria that residents will need to meet before they can be given a State lease (title). Some community leaders that were interviewed suggested that the Government should consider issuing titles to people who have built houses in informal settlement and lived there for at least 10 years. It may be a daunting task to determine how many years a resident has continuously lived in a particular settlement. In order to develop workable criteria, the upgrade implementing agency should develop the criteria in collaboration with key stakeholders including representatives of various groups of people that live in the settlement. It is important to provide appropriate information to residents that meet requirements for the issuance of State lease on the procedures and costs associated with the lease. For people who occupied customary land, there is a need for them to provide a proof of ownership of the land before formalizing their lands. As constructing infrastructure in an area needs land, it is important to have consultation with the residents during planning of the upgrade project and landowners where appropriate. This has the potential to reduce the tendency of some residents resisting the use of portion of the land where they live for constructing infrastructure, and has the potential to garner support from landowners for the program. It is important to note that housing problem in urban areas can be addressed if low-income population has access to urban land which should be followed by proper urban planning and government intervention in the urban land market as reported by

Yap (

2016) in a study of low-income housing policies and practices in Asia.

The findings show that residents would pay for service charges associated with the infrastructures that have been constructed as a result of the upgrade project. This suggests that informal residents are aware that the infrastructure and services provided during the upgrade project will need to be paid for. Thus, government has a lot to gain from the project, especially if it is implemented properly. The service charges paid by residents for water and electricity will boost government revenue. It can also boost some businesses in the settlements, which can create more jobs. Currently, some informal settlement residents access piped water and electricity through illegal means and government lose revenue as a result of leakages. If a proper upgrade project is implemented, it has the potential to block the leakages and the government will also get money from building permits and ground rent. It is important to note that though residents of informal settlements may be excited to see Water PNG connecting water pipes in their areas some of them may move to other informal settlements that have not been upgraded because of the service charges that come with it. This is in line with the findings of

Watt (

2020) who found in a Fijian study that some residents of an upgraded informal settlement moved to settlements that have not been upgraded.

One of the characteristics of a typical informal settlement is often the presence of temporary (makeshift) houses, especially in squatter settlements. However, in some cases, permanent houses are constructed even in squatter settlements. People who constructed permanent houses often have higher tendency to resist an upgrade project that may result in the loss of part of their house than those who have makeshift houses. As the upgrade of an area is associated with transaction costs, it is important to consider the characteristics of houses (whether makeshift or permanent). In our study, we found that more than 50 percent of the interviewees lived in permanent houses. This indicates that there may be vast negotiations during the upgrade project especially if some of the permanent houses are located in areas where infrastructures are to be constructed. It is important to do a thorough negotiation that can result in a “win–win” situation for both residents and the government, and for landowners in the case of informal settlements on customary land. The informal settlement residents should be satisfied with the upgrade project before implementation as reported by

Li and Wu (

2013). This will provide the upgrade implementing agency an idea of the potential cost of the upgrade.

In terms of decision to live in a makeshift house, we found that the main drivers include the ownership of a house in the settlement, frequency of crime in the neighborhood, land ownership type and occupation. It is important to consider these factors in planning an informal settlement upgrade project. Residents who owned a house in an informal settlement were likely to live in a makeshift house. This suggests that people who could not afford housing in formal settlements tend to move to informal settlements where they construct a temporary shelter. Thus, makeshift houses appear to contribute to providing affordable housing to low-income households and people who do not have a steady job. Thus, before implementing an upgrade project, it is important to consider that the upgrade has the potential to increase house prices in the informal settlement, which can restrict access to affordable housing to low-income households. This conforms with the assertion of

Lees et al. (

2016), who concluded that upgrade would increase land and house prices. The upgrade project has the potential to attract infrastructure and services to informal settlement and most makeshift houses converted to permanent houses. The infrastructure and services contribute to increase in house prices which may be above what some households can afford. In order to address the potential housing affordability problem triggered by the upgrade of informal settlements, the government should consider facilitating the construction of affordable houses in the settlement so that low-income households can have access to houses they can afford.

Informal settlements are often associated with high rates of crimes. Our findings show that neighborhoods dominated by makeshift houses are likely to be associated with frequent crimes. A possible reason for the frequent crime in the neighborhoods is that some of the residents who live in makeshift houses are unemployed and they are more or less people on transit. As the houses there are temporary, people who are engaged in crime can easily move away from their abodes without any trace. This may provide them an incentive to live in makeshift houses. Our findings are in line with that of

Naceur (

2013) who found that upgrading of informal settlements has a positive effect on the perception of safety in settlements in Batna, Algeria. If the intention is to address the issue of safety in the informal settlements of Port Moresby, the focus should be on areas dominated by makeshift houses because these tend to be crime hotspots. Furthermore, some criminals tend to use makeshift houses as their hide-outs.

We found that informal settlement residents who lived in houses built on State-owned land were less likely to live in a makeshift house. This indicates that the upgrade project may be associated with a lot of transaction costs with people who occupy State-owned land as a result of negotiations linked to land where infrastructure should be constructed. State-owned land which is often desired by developers is almost exhausted (

Wangi and Ezebilo 2017). Thus, the occupants of State-owned land in the settlement may find it difficult to release a portion of the land for establishing infrastructure. In negotiations with the occupants of State-owned land, the implementing agency should remind them that the land belongs to the government. Thus, the government is obliged to use portion of the land for constructing infrastructure.

The findings revealed that government workers who lived in informal settlements were less likely to live in makeshift houses. A possible reason may be that the workers get their salaries regularly, which gives them the opportunity to either pay for house rent in a permanently constructed house or to construct their own permanent house. It is important to note that residents of informal settlements come from all walks of life, including government workers. Thus, it is important to conduct a socio-economic impact assessment and potential ways to manage shocks that may arise before implementing the upgrade project. This will assist both the implementing agency and settlement residents to be fully prepared to host and implement the project.

If the intention is to upgrade informal settlements, it is important for the upgrade planners and policy makers to understand that settlement is part of the urbanization process and contribute to providing affordable housing for the low-income households. Informal settlements should not be perceived as an urban problem. It should be seen as part of the solution to affordable housing for the low-income households. It is important for the process of the upgrade to be simple, cheap and provide good results within the short term. In order to engender local community’s support, it is important to provide improvements that are visible to them within a short term. If the upgrade project is implemented in an effective and efficient manner, it can improve the social capital and welfare of informal settlement residents. It is important to note that upgrading informal settlements may encourage the emergence of new settlements and increase in house prices above what majority of residents can afford. Thus, these should be considered before implementing an informal settlement upgrade. A potential way to address the concern of the emergence of new informal settlements is to provide an effective mechanism to discourage the emergence of new settlements. The government should consider using economic instruments such as fine and rewards. This involves developing a mechanism that makes people who develop a new informal settlement to pay a fine of an agreed amount to government every fortnight. People who report the informal development to government are rewarded in cash. Affordable housing in an upgraded informal settlement can be promoted by facilitating large scale private developers to construct low-cost houses there. However, leadership, political will and the recognition of the needs of informal settlements are required in the upgrade policies as found by

Jones (

2017) in Indonesian study of the position of informal settlements in sustainable urbanization policy and strategy