Developing Multimodal Narrative Genres in Childhood: An Analysis of Pupils’ Written Texts Based on Systemic Functional Linguistics Theory

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. From a Literacy Approach to a Literacy Education

1.2. Multimodal Texts

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Our Research

- Deconstruction stage: In this stage, children became aware of the multiple narratives surrounding them, and were able to notice and reflect on their components and function. As the children were still not confident writers, this stage was developed mostly orally. They also incorporated their own narrative repertoire, based on traditional tales, popular culture and audio-visual media.

- Joint construction stage: This stage was usually designed as a game—guessing games, role play, cops and robbers, etc.—in which the children, organised into groups, were asked to perform a task related to the deconstruction stage. All the tasks contained a multimodal approach.

- Individual construction stage: In this stage, the children had to carry out a task similar to the one of the previous stage, in pairs or individually. They were given some freedom, so they were permitted to make choices and connect the task with their daily life and experience. Frequently, the products generated were displayed or read aloud in the classroom.

- To describe the multimodal written texts produced by children aged 7 to 8 years old.

- To analyse the intersemiosis of multimodal children’s writing and its relation with the overall development of literacy in young children.

- To interpret the construction of meaning of multimodal written texts in the school, taking into account the nature of children’s literacy experiences acquired out of school.

2.2. Research Design, Description of Participants, and Data Collection

2.3. Ethics

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Analysis of Sara’s Tale

3.1.1. Ideational Metafunction

3.1.2. Interpersonal Metafunction

3.1.3. Textual Metafunction

3.2. Analysis of Marina’s Tale

3.2.1. Ideational Metafunction

3.2.2. Interpersonal Metafunction

3.2.3. Textual Metafunction

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- McKenzie, S. Social Sustainability: Towards Some Definitions; Hawke Research Institute Working Paper Series, 27; Hawke Research Institute University of South Australia: Magill, Australia, 2004; Available online: https://www.unisa.edu.au/siteassets/episerver-6-files/documents/eass/hri/working-papers/wp27.pdf (accessed on 20 November 2020).

- Eizenberg, E.; Jabareen, Y. Social Sustainability: A New Conceptual Framework. Sustainability 2017, 9, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Powell, S.; Somerville, M. Drumming in excess and chaos: Music, literacy and sustainability in early years learning. J. Early Child. Lit. 2018, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somerville, M.; Green, M. Children, Place and Sustainability; Palgrave MacMillan: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Dyson, A.H. Donkey Kong in Little Bear country: A first grader’s composing development in the media spotlight. Elem. Sch. J. 2001, 101, 417–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kress, G. Before Writing: Rethinking the Paths to Literacy; Routledge: London, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Mills, K.A. The Multiliteracies Classroom; Multilingual Matters: Bristol, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Mills, K.A.; Exley, B. Time, space, and text in the elementary school digital writing classroom. Writ. Commun. 2014, 31, 368–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ranker, J. Redesigning and transforming: A case study of the role of the semiotic import in early composing processes. J. Early Child. Lit. 2009, 9, 319–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mills, K.A.; Unsworth, L. Multimodal literacy. In Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Education; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2017; pp. 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stein, P. Multimodal Pedagogies in Diverse Classrooms: Representation, Rights, and Resources; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Kalantzis, M.; Cope, B. Literacies; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Unsworth, L. Image−language interaction in text comprehension: Reading reality and national reading tests. In Improving Reading in the 21st Century: International Research and Innovations; Ng, C., Bartlett, B., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2017; pp. 98–108. [Google Scholar]

- Halliday, M.A.K. Towards a language-based theory of learning. Linguist. Educ. 1993, 5, 93–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halliday, M.A.K.; Hasan, R. Language, Context and Text: Aspects of Language in a Social-Semiotic Perspective; Deakin University: Waurn Ponds, Australia, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Eggins, S. An Introduction to Systemic Functional Linguistics; Continuum: New York, NY, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Lemke, J.L. Ideology, intertextuality, and the notion of register. In Systemic Perspectives on Discourse; Benson, J.D., Greaves, W.S., Eds.; Ablex: Norwood, NJ, USA, 1985; pp. 275–294. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, J.R. English text. In System and Structure; John Benjamins: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Halliday, M.A.K. Language as Social Semiotic; Edward Arnold: London, UK, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Van Leeuwen, T. Introducing Social Semiotic; Routledge: London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Kress, G. Multimodality: A Social Semiotic Approach to Contemporary Communication; Routledge: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- De Silva Joyce, H.; Feez, S. Text Based Language and Literacy Education: Programming and Methodology; Phoenix Education: Putney, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, J.R. Analysing genre: Functional parameters. In Genre and Institutions: Social Processes in the Workplace and School; Christie, F., Martin, J.R., Eds.; Continuum: London, UK, 2000; pp. 3–39. [Google Scholar]

- Butt, D.; Fahey, R.; Feez, S.; Spinks, S. Using Functional Grammar: An Explorer’s Guide; Macmillan Education Australia: South Yarra, Victoria, Australia, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Rose, D.; Martin, J.R. Learning to Write, Reading to Learn: Genre, Knowledge and Pedagogy in the Sydney School; Equinox: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Lavid, J.; Arús, J.; Zamorano-Mansilla, J.R. Systemic Functional Grammar of Spanish: A Contrastive Study with English; Continuum: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Rose, D. Genre in the Sydney school. In The Routledge Handbook of Discourse Analysis; Gee, J.P., Handford, M., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2012; pp. 209–225. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, J.R.; Rose, D. Genre Relations: Mapping Culture; Equinox: London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Somerville, M. Separation and Connection: Children Negotiating Difference. In Children, Place and Sustainability; Somerville, M., Green, M., Eds.; Palgrave MacMillan: London, UK, 2015; pp. 143–165. [Google Scholar]

- Bateman, J.; Wildfeuer, J.; Hiippala, T. Multimodality: Foundations, Research and Analysis a Problem-Oriented Introduction; De Gruyter-Mouton: Berlin, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Jewitt, C.; Bezemer, J.; O’Halloran, K. Introducing Multimodality; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- O’Halloran, K.L.; Tan, S.; Wignell, P. SFL and multimodal discourse analysis. In The Cambridge Handbook of Systemic Functional Linguistics; Thompson, G., Bowcher, W.L., Fontaine, L., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Halliday, M.A.K.; Matthiessen, M.I.M. Halliday’s Introduction to Functional Grammar; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Kress, G.; van Leeuwen, T. Reading Images. The Gramar of Visual Design; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Rose, G. Visual Methodologies. An Introduction to the Interpretation of Visual Materials; Sage: London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Painter, C. Image analysis using Systemic-Functional Semiotics. In Critical Content Analysis of Visual Images in Books for Young People. Reading Images; Johnson, H., Mathis, J., Short, K.G., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2019; pp. 23–38. [Google Scholar]

- Moya Guijarro, A.J. A Multimodal Analysis of Picture Books for Children: A Systemic Functional Approach; Equinox: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Painter, C.; Martin, J.R.; Unsworth, L. Reading Visual Narratives: Image Analysis in Children’s Picture Books; Equinox: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Jewitt, C. Multimodality and literacy in school classrooms. Rev. Res. Educ. 2008, 32, 241–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Silva Joyce, H.; Feez, S. Exploring Literacies: Theory, Research and Practice; Palgrave MacMillan: Hampshire, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Bateman, J.A. Text and Image: A Critical Introduction to the Visual/Verbal Divide; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Jewitt, C. An introduction to multimodality. In The Routledge Handbook of Multimodal Analysis; Jewitt, C., Ed.; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 15–30. [Google Scholar]

- Baldry, A.; Thibault, P.J. Multimodal Transcription and Text Analysis: A Multimedia Toolkit and Coursebook; Equinox: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- O’Halloran, K.L. Systemic Functional-Multimodal discourse analysis SF-MDA: Constructing ideational meaning using language and visual imagery. Vis. Commun. 2008, 7, 452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iedema, R. Resemiotization. Semiotica 2001, 137, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kress, G. Against arbitrariness: The social production of the sign as a foundational issue in critical discourse analysis. Discourse Soc. 1993, 4, 169–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinec, R.; Salway, A. A system for image-text relations in new (and old) media. Vis. Commun. 2005, 4, 337–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, J.R. Construing knowledge: A functional linguistic perspective. In Language, Knowledge and Pedagogy; Christie, F., Martin, J.R., Eds.; Continuum: London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein, B. Pedagogy, Symbolic Control and Identity. Theory, Research, Critique; Taylor & Francis: London, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Bruner, J.S. Actual Minds, Possible Worlds; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Hyland, K. Genre and Second Language Writing; The University of Michigan Press: Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Bruner, J.S. The role of dialogue in language acquisition. In The Child’s Conception of Language; Sinclair, A., Jarvella, R., Levelt, W.J.M., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1978; pp. 241–255. [Google Scholar]

- Bateman, J. Multimodality and Genre: A Foundation for the Systematic Analysis of Multimodal Documents; Palgrave-Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- García-Jiménez, E.; Guzmán-Simón, F.; Moreno-Morilla, C. Literacy as a social practice in pre-school education: A case study in areas at risk of social exclusion. Ocnos. Rev. Estud. Sobre Lect. 2018, 17, 19–30. Available online: https://doi.org/10.18239/ocnos_2018.17.3.1784 (accessed on 20 November 2020).

- Parnell, R.; Patsarika, M. Young people’s participation in school design: Exploring diversity and power in a UK governmental policy case-study. Child. Geogr. 2011, 9, 457–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloome, D.; Power Carter, S.; Morton Christian, B.; Otto, S.; Shart-Faris, N. Discourse Analysis & the Study of Classroom Language & Literacy Events. A Microesthnographic Perspective; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Knapp, P.; Watkins, M. Genre, Text, Grammar: Technologies for Teaching and Assessing Writing; UNSW: Sydney, Australia, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Bearne, E. Assessing children’s written texts: A framework for equity. Literacy 2017, 54, 74–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arús Hita, J. Theme in Spanish. In The Routledge Handbook of Systemic Functional Linguistics; Bartlett, T., O’Grady, G., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 194–212. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, Z. Illustrations, text, and the child reader: What are pictures in children’s storybooks for? Read. Horiz. 1996, 37, 130–142. [Google Scholar]

- Nikolajeva, M.; Scott, C. The dynamics of picturebook communication. Child. Lit. Educ. 2000, 31, 225–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moya Guijarro, A.J.; Pinar Sanz, M.J. On interaction of image and verbal text in a picture book. A multimodal and systemic functional study. In The World Told and the World Shown; Ventola, E., Moya Guijarro, A.J., Eds.; Palgrave MacMillan: London, UK, 2009; pp. 107–123. [Google Scholar]

- Bearne, E. Multimodality, literacy and texts: Developing a discourse. J. Early Child. Lit. 2009, 9, 156–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iedema, R. Multimodality, resemiotization: Extending the analysis of discourse as multi-semiotic practice. Vis. Commun. 2003, 2, 29–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kress, G.; van Leeuwen, T. Multimodal Discourse: The Modes and Media of Contemporary Communication; Arnold: London, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

| Registers | Language | Meanings | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Field | Ideational metafunction | Experiential | Express the experience of the world through language (transitivity system). |

| Tenor | Interpersonal metafunction | Interpersonal | Express the nature of the relation between the author and the reader, and the attitude of the author towards the theme exposed (mood types, system of polarity and system of modality). |

| Mode | Textual metafunction | Textual | Determines the way in which a text—oral or written—is organised, its relation with previous texts and the surrounding context (thematic organization). |

| Genre | Sessions | Products Generated |

|---|---|---|

| Narrative | Four | Written multimodal stories about Halloween. |

| Written story narrating the sequence of a set of drawings. | ||

| Written multimodal narration of a movie or episode in a three-stage sequence. | ||

| Written postcards narrating where the children have travelled, what they are doing there, what do they like most and what do they miss. | ||

| People description | Two | Robot sketches, and texts of cartoon characters described. Written descriptions of people following a scheme provided. |

| Ambience description | Four | Drawings of landscapes previously described orally. Brief written descriptions and their drawings. |

| Oral descriptions of landscapes and interior spaces. | ||

| Oral landscape descriptions and drawings following a provided scheme. | ||

| Oral and written landscape descriptions, and their drawings. | ||

| Other genres | Two | Written recipes.Drawings about jobs infrequent among women, and a written motto for each of them. |

| Data Gathering | Number | Duration |

|---|---|---|

| Children’s products | 240 | |

| Photographs | 540 | |

| Sets of notes containing field observation | 47 | |

| Video and audio recordings | 29 | 1020 min. |

| Metafunction | Language | Visual |

|---|---|---|

| Ideational | Characters: what information is provided, and what is the relation between them. Narrator: who tells the story. Topics, themes or features inspired in traditional tales. Intertexts from the popular culture: television, videogames, internet, etc. Organisation of the processes (verbal and mental actions) and relation between the different parts of the narrative sequence. Use of background detail to create mood and setting. Description of the spatial and temporal frame. | Character’s depiction: complete (including head) or metonymic (parts of the body, shadow, silhouette…). Character’s appearance and reappearance. Contrast between different characters as a manifestation of their relations. Means for transmitting pathos and affect, such as the images’ face expressions, or drawing details (naturalism). Depiction of secondary characters. Processes: actions, verbal, mental (cognition or perception). Inter-event options: What happens between one image and the following. Circumstances: Depiction of the context and its changes. What does the image add to the text? Hypothetical ideational contradiction between text and image. |

| Interpersonal | The view of the narrator, and the means used to implicate the reader in the text (relations of power between the narrator, the characters and the reader). Use of language appealing the reader (references, interpellations, etc.). Language means to connect to the reader’s empathy. Use of narrative/informational structure and language to engage and hold the reader’s attention. Use of modality in the text. Selection, adaptation, synthesis and shaping of content to suit personal intentions, ideas and opinions. | Focalisation (mediated or unmediated; through contact or observation). Means for depicting social distance. Attitude: involvement and power. Means for transmitting pathos and affect, such as the images’ face expressions, or drawing details (naturalism). Ambience: Use of bright, plain or dark colours to attract attention or highlight characters and actions. Effects of the colour on the reader. |

| Textual | Integration and balance of modes for design purposes. Choice of language, punctuation, font, typography, layout and presentational techniques to create effects and clarify meaning. Choice of the mode(s) that will support informative, communicative and expressive purposes. Handling of technical aspects and conventions of different kinds of texts. Marked and unmarked clauses and change of the usual clause structure. Text marks (connectors) between the different parts of the narrative sequence. Choice and use of a variety of sentence structures for specific purposes. Use of concrete or abstract language. Explanation of the choices of mode(s) and expressive devices including words. | Visual organisation and focus. Layout of verbiage and image (integrated or complementary). In complementary layout, which mode is privileged (verbiage or image). Manifestation of meaning (locution or idea) in integrated layout (more likely through bubbles). Framing: detachment of images from verbiage. Relation of the characters and the action with the frame. |

| |

| Language transcription | Visual transcription |

“and then they found a room and suddenly it moved, the wardrobe, and she opened it, Alba, and then it came out, a monster”. | There is a big wardrobe in the left part of the image. In the bottom there is a desk, and the drawings of two girls, named Marina and Sara, who is standing on a bedside table. There is a spider on the table, and two more spiders with a web in the upper right of the image. A bubble in the verbiage reads “jijiji” on the left, and another one on the right. In the lower part, the girl named Marina says “Oh what”, the other girl is named Sara. The doors of the wardrobe may be opened, and inside there is a mummy, much bigger than the two girls. |

| Marina’s Story | Language Transcription | Visual Transcription | |

|---|---|---|---|

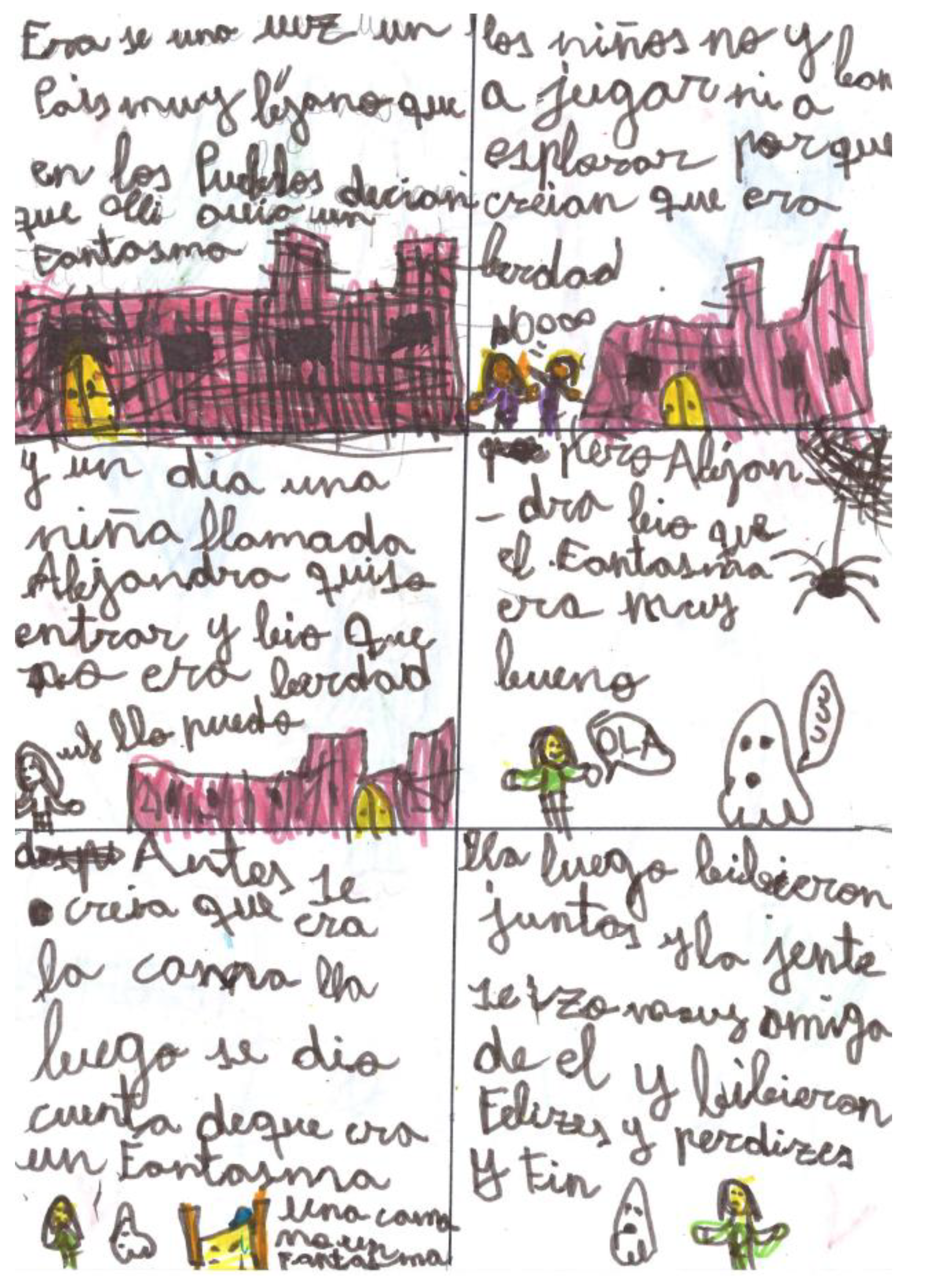

| 1 |  | Once upon a time a faraway land that in the villages they said there was a phantom. | The verbiage is situated in the upper part of the vignette, while the castle’s image occupies the lower part. |

| 2 |  | The children didn’t go to play or explore because they thought it was true. | The castle remains in the lower part of the vignette, where two characters have appeared, one of them saying: “Noooo”. |

| 3 |  | And one day a girl called Alejandra wanted to enter and she saw it wasn’t true. | The castle is in in the lower part of the image, and it has appeared a new character, Alejandra, saying: “Uf I can”. |

| 4 |  | What But Alejandra saw that the phantom was very good. | The castle has disappeared and in the lower part of the image appear Alejandra saying “Hello” and the phantom saying “Uuu”. There is a spider hanging from its web in the upper right corner. |

| 5 |  | Aft Before she thought that it was the bed and then she noticed it was a phantom. | In the lower part of the image there are Alejandra and the phantom, and a bed, with an explanation: “A bed, not a phantom”. |

| 6 |  | And then they lived together and the people become close friend of him and they lived happily ever after and end. | The characters of the phantom and Alejandra remain in the lower part of the vignette. |

| 7 |  | And end. Alejandra and the monster. Signature. | The back side of the sheet combines text and the images of the phantom and Alejandra. Other ornaments are present, such as stars and hearts in different bright colours. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Pacheco-Costa, A.; Guzmán-Simón, F. Developing Multimodal Narrative Genres in Childhood: An Analysis of Pupils’ Written Texts Based on Systemic Functional Linguistics Theory. Educ. Sci. 2020, 10, 342. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci10110342

Pacheco-Costa A, Guzmán-Simón F. Developing Multimodal Narrative Genres in Childhood: An Analysis of Pupils’ Written Texts Based on Systemic Functional Linguistics Theory. Education Sciences. 2020; 10(11):342. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci10110342

Chicago/Turabian StylePacheco-Costa, Alejandra, and Fernando Guzmán-Simón. 2020. "Developing Multimodal Narrative Genres in Childhood: An Analysis of Pupils’ Written Texts Based on Systemic Functional Linguistics Theory" Education Sciences 10, no. 11: 342. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci10110342

APA StylePacheco-Costa, A., & Guzmán-Simón, F. (2020). Developing Multimodal Narrative Genres in Childhood: An Analysis of Pupils’ Written Texts Based on Systemic Functional Linguistics Theory. Education Sciences, 10(11), 342. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci10110342