Abstract

How the Swedish after-school leisure program pedagogy relates to special education is rarely the subject of research. The problematization of the special education concept in the after-school leisure centers will be the starting point of this analysis model. This has been constructed with the aim of investigating how actors in the Swedish after-school leisure activities define how special education is being actualized in after school programs. The premises for the study regard the after-school leisure program mission; namely, to complement, compensate, and teach. In order to validate the analysis model, an exploratory pilot study was conducted through interviews with two teacher educators and two teachers in the after-school leisure program. The results show that the models developed for this investigation can be used in further studies. The analysis model provided important key words for further investigation and discussion of the program. These results can in no way be generalized, but they clearly show that the constructed and tested analysis model may form the basis for valuable discussions and pedagogical approaches in teacher education and in the program that the education prepares students for. Therefore, the pilot study comprises the foundation for a more comprehensive future study.

1. Introduction and Background

In international agreements, the compulsory school ordinance and curricula state that segregation in school and school-age childcare should be avoided [1,2,3]. Notwithstanding, pupils are being regularly placed in special types of school, where the teaching is mostly done in special groups in special localities and with special teachers.

Compulsory school for pupils with learning disabilities is a special form of school, which, in addition to the regular education system, has been established for people with learning disabilities. The Education Act states that children who are judged not to be able to reach the compulsory school knowledge requirements, because they have a developmental disorder and must be accepted in the Compulsory school for pupils with learning disabilities [4]. Pupils in this school are a heterogeneous group. Children with mild developmental disorders are often on the borderline between primary school and compulsory school for pupils with learning disabilities.

Within the compulsory school for pupils with learning disabilities, there is a specialization, called compulsory school, for children with severe learning disabilities. This school is intended for pupils who cannot assimilate into all or parts of the special school’s curricula. A decision on admission to compulsory school for pupils with learning disabilities shall be preceded by an investigation that includes a pedagogical, psychological, medical, and social assessment. Intelligence tests are the most important starting point for reception to this type of school. A value that is below 70 in IQ marks the criteria for entering compulsory school for children with learning disabilities.

At the end of school, after-school leisure centers provide activities for all pupils, regardless of the various school types. Since the end of the 1970s, the afterschool center’s main task has been caring and nursing for children of early school age after the end of school. Leisure centers have had to redefining and reconstructing goals and tasks. Because of this, governing documents have been replaced, the groups of children have been expanded, and the staff have often been given more responsibilities [5].

Leisure educators, since the advent of the profession in 1966, have given much room for relationship-oriented pedagogy [6] and they have often entered the role of protector for the “vulnerable children” represented [7]. Children’s social skills are central to the profession, as confirmed in a study that compared preschool teachers, leisure educators, and primary school teachers [8]. Today, more than 80% of Sweden’s 6–9-year-olds are enrolled in leisure centers. In light of this, it is surprising that relatively few studies and research projects have addressed this activity and professional group. The leisure centers have seldom separated their activities into “normal activity” and “special activity”. The pedagogical approach at the leisure centers has a clear goal to bring together all children in inclusive activities.

From having been more oriented toward care and social pedagogy, the after-school program is now a more noticeable feature in an overall education system [3]. As the demand has grown stronger for the after-school center to be a learning environment, the societal, social, and collective goals have receded in the background for more individualistically nuanced arguments and goals, which, in many cases, have consequences for resource-poor children to participate in activities. There has been a drastic increase in categorization and selection for special teaching groups and school forms over the last two decades [9]. In school and in leisure-time activities, there is a clear segregating development for children in need of special support.

The principle that has long guided the after-school leisure program, “to avoid segregation and special solutions and instead raise the quality of regular activities so that everyone has one’s needs met there”, has been greatly weakened [10] (pp. 30–31). For example, there has been a sharp increase in the special, segregated after-school activities for children attending special schools. For comparison, based on 19 municipalities, there was a 375 percent increase in the number of special school children in segregated after-school activities between 1997–2011 [7]. The National Agency for Education, Agency for Special Needs Education, Statistics Sweden, and the Swedish Schools Inspectorate were contacted to obtain current data on the increase in special after-school leisure centers. Unfortunately, none of these authorities had any statistical data on these issues. No follow-up studies have been carried out, but there are clear signs from the field that this development is continuing in Sweden.

At the same time as the after-school leisure program has been steered toward a clearer learning mission, the tasks of the leisure-time teachers in school have increased, and many now divide their teaching duty between the compulsory school and the non-compulsory after-school activities. In addition to this, a new teacher education program, compulsory school teacher for the after-school leisure program, has opened the way for more subject-oriented and individualized learning in the leisure program activities. Teaching is now a key concept that is to be defined and grounded in a program, where terms, like learning and learning processes, have become more familiar. This pedagogical change in direction can easily lead to children in the after-school leisure program being compared and assessed with norms that are related to school, knowledge expectations, and the behavior that is required in compulsory school.

There are other factors influencing the conditions for treatment children defined in the compulsory school as needing special support. The number of children in the after-school leisure program has doubled in a short time, at the same time as the proportion of staff lacking pedagogical training has increased [11]. There are also signs that many after-school programs have had to give up their pedagogical ambitions. Time is spent on the compulsory school program, which results in difficulties in planning and carrying out activities after school. In addition, when school time is over and the voluntary leisure program activities begin, pupils with special support often lose their extra resource, such as support from a pupil assistant. All of these circumstances have contributed to decreasing the chances of fulfilling the mission to compensate [11].

1.1. Complement and Compensate

The after-school leisure program mission, to complement and compensate, is clearly addressed [12]. The right to an equivalent compulsory school is duly noted in several national reports, while the right to more equal conditions for upbringing and childhood is vaguely expressed. In addition, the after-school leisure program is not accessible to all children, which means that the mission of complementing and compensating does not reach the whole target group. The Schools Inspectorate review of after-school programs states that “Given the reduced equality in Swedish compulsory school, it is important to discuss the compensatory and complementary mission of the after-school leisure program. This importance can be linked to the follow-ups of the school knowledge results in recent years and changes worldwide” [13] (p. 24). Such evaluations and reports promote that the overall education system resources should be primarily used, so that all students pass in all subjects, although with extra focus on mathematics, Swedish, and English. The complementary and compensatory idea has been tied to subject results in school and not to other goals found in the curriculum. The complementary mission is clearly noted in the compulsory school curriculum, Lgr 11, “Teaching in the after-school leisure program complements the preschool class and school by means of the learning to a greater extent being situation-driven, experience-based and group-oriented and based on the pupils’ needs, interests and initiatives” [3] (p. 22). Given this assignment, teachers in the after-school leisure program seek a school pedagogical approach, which is often described as “schoolification” taking place [14,15,16,17].

The professional role of teachers in the after-school leisure program is difficult to define, due to the existing hierarchies between teachers in the compulsory school and the balance of power that exists between teacher categories [18,19]. Many teachers in after-school leisure programs try to gain legitimacy, adapting to their teaching colleagues and principals’ expectations in fulfilling their complementary assignment [20], while others take a different approach that is more similar to the after-school leisure program pedagogy that prevailed before the mission extended toward schooling [21].

Clearly, complementing lies close to compensating, with the after-school leisure program having the mission of compensating the shortcomings of the school in order to develop subject-knowledge in all students. Here, there is an expressed desire “to integrate academic knowledge and the traditional play, care and learning in a new way of thinking about education” [12] (p. 214). The assignment to compensate subject-knowledge is explicated in comments to the after-school leisure program in the fourth part of the curriculum. The terms emotional engagement, direct and concrete experiences, and experience-based learning are used to describe this learning [3,22]. This compensatory mission of the after-school leisure program is not explicitly stated in the curriculum, but the General guidelines for after-school leisure programs [23] clearly formulates it: the after-school leisure program, like the preschool class and school, has a compensatory mission. This means to strive to offset the differences in pupils’ abilities in order to acquire the education [23] (p. 20).

1.2. Normality and Compensation

There is every reason to problematize and object to the concept of compensating [24]. Compensatory efforts work towards meeting certain norms and, in turn, shaping what is defined as normal. Consequently, normality is linked to clear norm-setting, which indicates what is desirable. Normalization then becomes striving after achieving what is deemed to be appropriate by having individuals change in some way [25]. This is contrary to the principle of inclusion; there should be room for children’s differences. The concept of adaptation works better here, while assuming that the child is not to be adapted, but rather the environment should be set up according to the child’s needs [24]. Normality and deviation are created in interaction in a given context; thereby, normality is a relative concept [25]. The implication is that what is perceived as deviant or normal is constructed in a setting that is characterized by its conditions, with traditions and current policy documents having uncontested influence.

Thus, normal or deviant is intertwined with what is expected, desirable, or sought after in every context. The educational basis and demands of the program constitute the premises for when a child crossing the line for normalcy is defined as needing special education. If the pupil cannot meet the requirements for normality, then compensatory activities can be performed to shape the child to resemble the established norm [26]. Such an approach naturally limits children’s opportunities to be different and, over time, can mean that a child is separated into a special program.

Norms have a clear connection to power [27]. What is deemed special and thereby norm-breaking emerges in relation to the demands, expectations, hopes, and ideas that exist in the after-school leisure program. Thus, the after-school leisure program becomes a societal institution with the power to decide who will be considered to be special. When a child shows deviant behavior, the diagnosis may function as a relief for both children and staff, by offering the child an identity where he or she can be understood through his or her diagnosis [28]. Diagnoses can also serve to assure the environment that the problem lies with the child and open doors in order to gain resources or legitimize a special program. The increase in diagnoses among school children in the last two decades shows that this course of action is not entirely uncommon [29,30,31].

1.3. Special Education

Special pedagogy is rarely the subject of research in the after-school leisure sector [32]. Children with special needs are offered what is traditionally defined as compensatory special education and, usually, the concept of complementary is associated with this orientation. The most common special education uses special teaching methods, strategies that are particularly adapted for pupils with less school ability. The methodology is usually practiced in special groups, focusing on compensation and skills. Often, core subjects are at the center of the program. Many times, the teaching is concentrated on difficulties and deviations, carried out by a small group of staff, which are usually separate from regular school activities. This type of program presents a greater risk for discrimination and stigmatization [33]. Another type of special education is inclusive, which was previously the organizational principle for pupils that are in need of special support, according to the School Law [4] and the School Ordinance [2]. The concept of inclusion is removed from the above-mentioned law and ordinance and it is missing from the curriculum and general guidelines for the after-school leisure program. An inclusive approach accepts children are different and, equality, participation and group-belonging are keywords in preventing exclusion and stigmatization. Therefore, special support in an inclusive arrangement is provided within the framework of the ordinary program activities. An inclusive after-school leisure program includes all pupils on equal terms, regardless of circumstances, interests, and abilities, and where all children feel safe and involved. For inclusion to be functioning, foremost is the feeling that one belongs to the group [34]. Making special education separate from other education, transferring it to a special program and special professional category, easily leads to expert thinking and segregation. Several international research results show that stigmatizing effects are caused by special support when organized in differentiating forms [35,36].

According to the National Agency for Education (2020), one of the most important duties in special education is to contribute to all pupils feeling community and full participation. Participation in its various forms is marked as important in the special educational work of making the teaching environment accessible to all.

2. Purpose

The purpose formulated for this exploratory pilot study is as follows:

to test a model for analyzing how stakeholders in the Swedish after-school leisure program, define how special education is being actualized in after school programs.

3. Methods

3.1. Analysis Model

In previous studies investigating the conditions for inclusion in school, an analysis model was constructed and further developed that was based on conclusions [33,37]. The analysis model, which is dichotomous in structure, presents two orientations for pedagogical work; these, in turn, have consequences for the view of normality and thus affect the conditions for inclusion. The model has been expanded with more concepts prior to this study. The first approach, called “the narrow”, has, as its main goal, to work toward the child/pupil fitting in the activity through using corrective and compensatory measures. The other approach, “the wide”, works primarily with adapting the environment to the child/pupil. In the compulsory school and the after-school leisure program, both are represented, with the wide approach expected to have a significant representation in the after-school leisure activities. The analysis may provide certain clues as to what a complementary and compensatory teaching mission might contain and how the concept teaching can be defined in the after-school leisure program. For an educator to work in both directions may not seem to be ideologically consistent and value-based, but this is possibly a condition for teachers in the after-school leisure program profession. This changed, partly new profession is described as a hybrid profession [38], i.e., a new profession that attempts to unite both the leisure-time educator’s and the schoolteacher’s professional identities in one and the same profession. The following description shows the two approaches that the after-school leisure program teacher may have to handle.

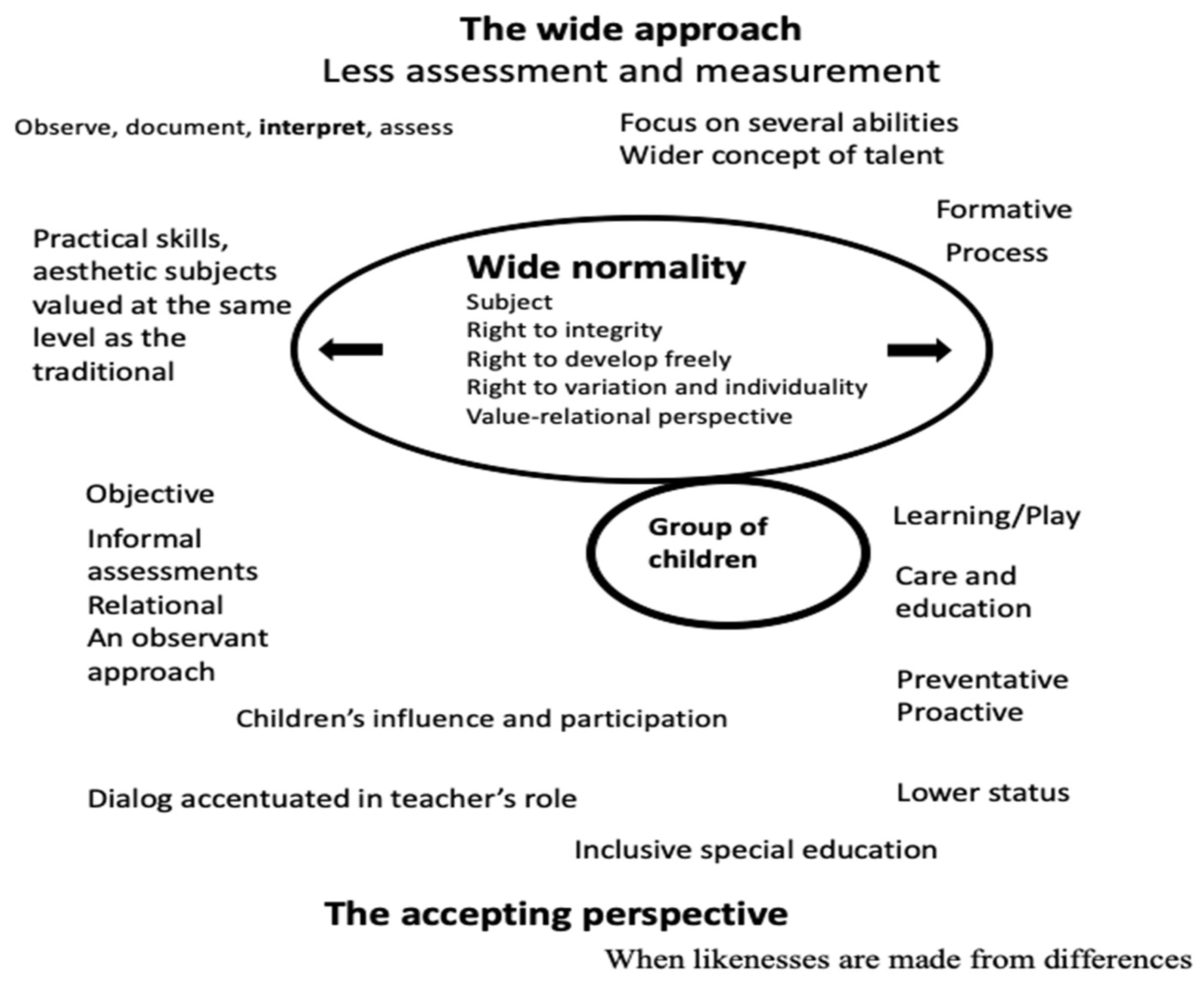

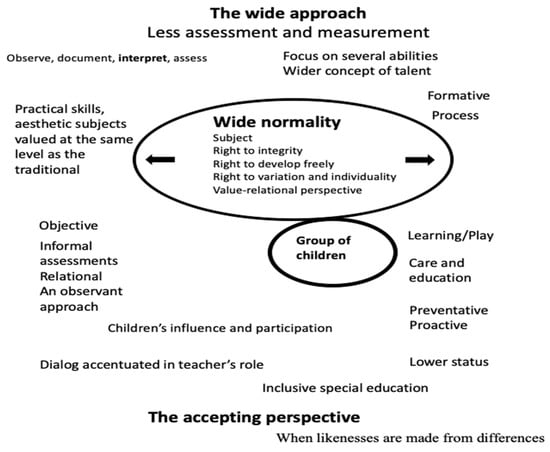

In the wide approach (Figure 1), the group and the process lie at the center. Here, assessment is toned down, and formative activities are directed towards the environment and pedagogical methods. The pupils’ overall abilities are most important, and there is a greater breadth of knowledge and abilities that are valued. Here, aesthetic subjects and practical skills have more space than in the narrow approach. In the wide program, the concept of learning dominates, and dialogue is central for the teacher. Learning through play is encouraged, with care and fostering prioritized. In wide leisure activities, there is a greater acceptance of differences, and compensation and correction are directed more to the environment and the teacher’s method than to the pupil. Working with values, such as democracy, empathy, and solidarity, is at the forefront. A value-relational method is thus accentuated in the wide perspective. The pupil’s influence and participation are real, in a process where target goals constitute guidance. Integration is a condition, and the goal is an inclusive program that is characterized by positive attitudes towards the group needing extra support. The risk of exclusion and discrimination is significantly less with this type of orientation [33]. The special needs teacher and special educator function as inclusion educators in this model.

Figure 1.

The wide approach (developed 2019 from Karlsudd, 2002, 2017 [33,37]).

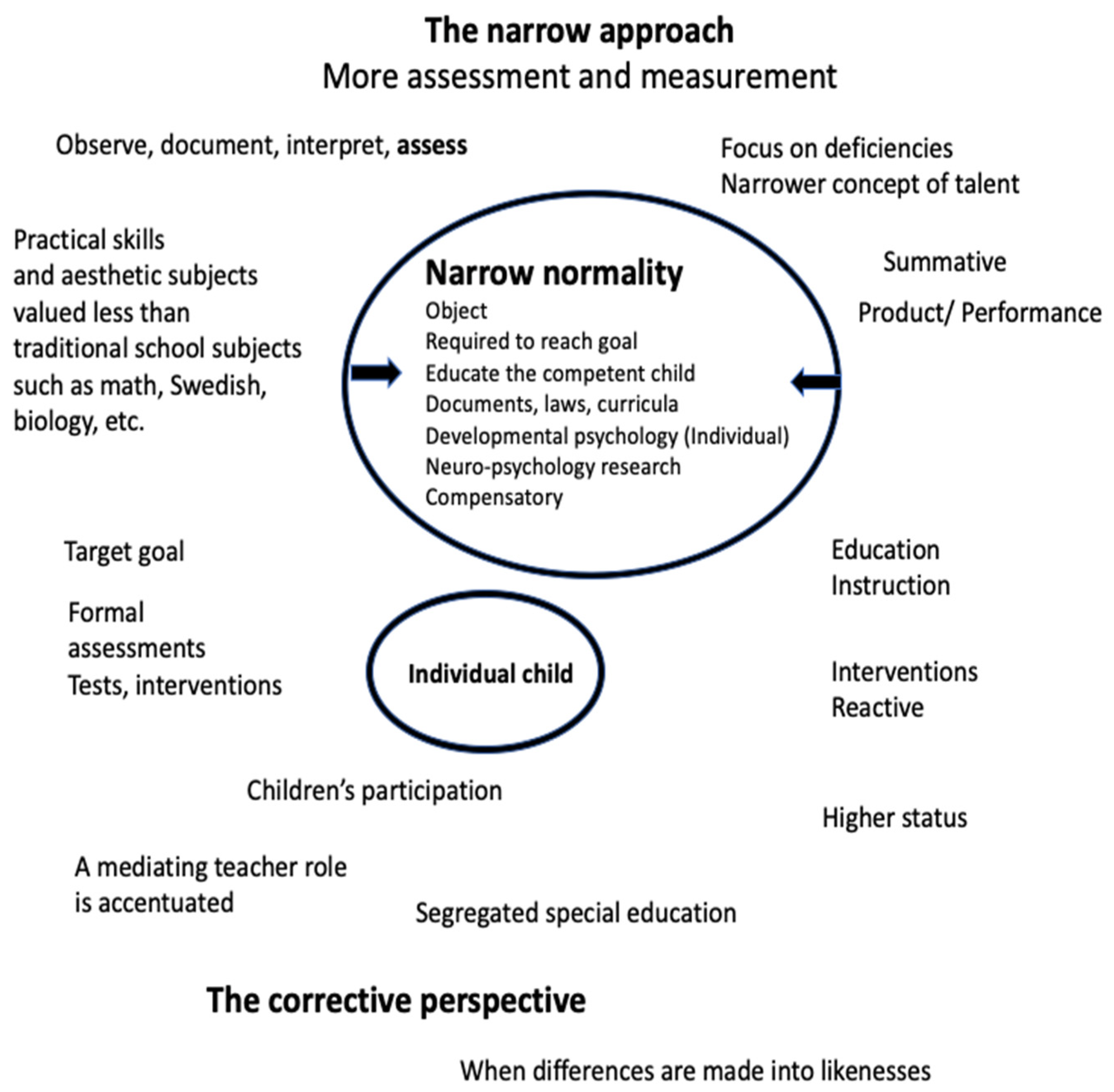

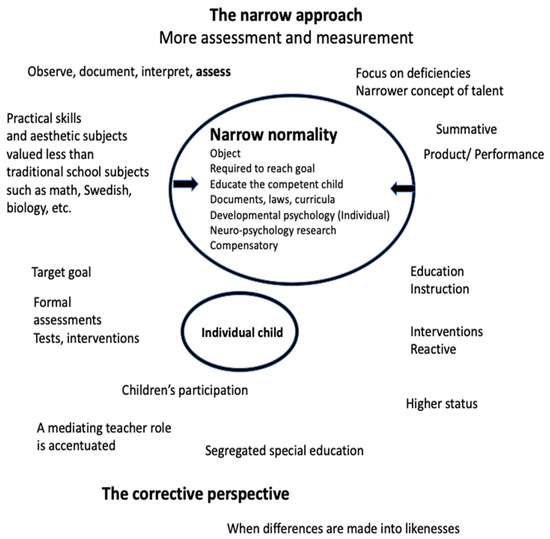

In the narrow approach (Figure 2), the individual pupil’s achievements are at the center and, for these to be made visible and developed, documentation, measurement, and assessment are key terms. The individual pupil’s performance is most important, and the knowledge and skills most valued are those that are related to traditional school subjects, such as Swedish and mathematics. In the narrow perspective, the concept of teaching dominates with the clear teacher role of a mediator. In the narrow program, the focus is on shortcomings in relation to the formulated achievement goals. Compensation and correction are directed more to the pupil than to the environment and the teacher’s method. Working with values, such as democracy, empathy, and solidarity, is more in the background than in the foreground. The pupils’ influence and participation are less than in the wide approach and they can be defined as collaboration. Education with a strong foothold in the narrow pedagogy reduces the opportunities for children and young people to be different.

Figure 2.

The narrow approach (developed 2019 from Karlsudd, 2002, 2017 [33,37]).

3.2. Pilot Study

An exploratory pilot study was conducted in order to test whether the constructed models (Figure 1 and Figure 2) can lead to a closer understanding how special education is being actualized in the after-school leisure program. The method of strategic selection was used to achieve diversity regarding the informants ages and experiences [39]. Two teacher educators working in the teacher education program for after-school leisure centers and two teachers in after-school leisure centers were interviewed (Table 1). Teacher educators are recognized for their experience and the implementation of education and training in the field. Thus, they are well acquainted with the governing document pertinent to the education sector. Teachers in after-school leisure centers on the other hand are actively involved in day-to-day practices of special activities.

Table 1.

The respondents in the interview survey.

Three female and one male participated in the interviews, which closely reflects the national gender distribution. Females make up approximately 70% of the leisure center’s staff members [40]. The youngest teacher educator was aged between 40–45 (R.1) and the other was aged between 60–65 (R.2) (Table 1). One of the teachers who represented the after-school center was aged between 45–50 (R.3) and the other teacher aged between 30–35 (R.4) (Table 1). For reasons of confidentiality, the exact age and years of experience is not stated. The respondents came from two counties and the teacher educators worked at different campuses.

Before the interviews, a letter, guaranteeing the upholding of the principles of research ethics, was sent to the respondents [41]. For this study, this mainly meant informing the participants of the aim of the study and that participation was voluntary. The data gathering was conducted through semi-structured interviews [39]. Each respondent was asked what the three concepts: complement, compensate, and teach meant with regards to the after-school leisure program pedagogy versus the after-school leisure program special education. What qualities, differences and similarities may be visible? With this approach, it was natural to ask relevant follow-up questions. The interviews that were recorded were conducted by telephone or video communication. No major difference was observed between the interviews that were conducted with audio only and those that combined audio and video. The time spent on the interviews was between 45–60 min. All of the interviews were conducted without interruption and the conversations could have been described as participatory and transparent. The technique of sentence concentration was used in the subsequent transcription. “Long statements are compressed into shorter statements, in which the essential meaning of what has been said is reformulated in a few words” [42] (p. 174). In the transcription, all interviews were anonymized. In order to increase the validity of the survey, a feedback of results and analysis was carried out with two of the respondents. A teacher educator from county A and a leisure teacher from county B. Both of the respondents perceived the results and analysis as credibly and correctly reproduced and had no objections or suggestions for changes.

4. Results

It was clear at the beginning of the interviews that the respondents were well acquainted with all basic concepts except for the after-school leisure center special education which raised some uncertainty; this was also anticipated. The three concepts that formed the basis for the interviews opened up for follow-up questions, and statements were categorized under a number of subheadings in the results.

Summarizing the interviews revealed that there were no major differences among the respondents’ perceptions. The teacher educators appeared to be very familiar with the work situation and with the view of the teachers’ mission in after-school programs, as the answers have a high degree of agreement.

4.1. After-School Leisure Program Pedagogy

All of the respondents believe that the pedagogy of the after-school leisure program is synonymous with inclusive pedagogy. All pupils’ equal value is central, and no one classifies and defines pupils, as in the compulsory school. Many parts of the after-school leisure program are free from assessment, and any assessment is from a comprehensive, permissive perspective. The complementary, compensating aspect is the focus.

4.2. After-School Leisure Program Special Education

The after-school leisure program staff did not have many reflections regarding a special educational approach, as the activities already have a clear inclusive position, say all the respondents. One states, “Special education is in the after-school leisure program pedagogy. One doesn’t think, now I am working in special education (R.3)”. Interventions that are characterized by a more traditional special education are initiated only when a child requires special techniques and methods, such as when a child needs alternative communication. The basic rule is to include all staff in these efforts, and they also often try to involve the whole group of children, like practicing sign language. The after-school leisure program tradition of teamwork is clear; when something is deemed to be special educational in the after-school leisure center, the staff collaborate. They discuss problem solutions together. “Maybe this is an aspect that distinguishes the after-school leisure program special education (R.1)”, says one interviewee.

4.3. Complement

In the after-school leisure program pedagogy, the complementary component is strong. The program offers activities that rarely or never occur in school. The educators strive for all children to be included in the activities and try to adapt the environment instead of working with compensatory efforts towards the pupil. There is no compulsion and no duty, or as one interviewee puts it, “One accepts if someone does not want to join (R.4)”.

4.4. Compensate

The respondents think that the compensatory mission in the after-school leisure program pedagogy seems to be more linked to the home, clubs, and culture. The after-school program may play an important nurturing role more now when, for example, gang crime increases in vulnerable areas. “Unfortunately, fewer children enroll in clubs and associations now (R.3)”, a respondent says/said. A more mediating character exists when compensatory special educational efforts occur in the school curriculum-driven instruction.

4.5. Teach

There is teaching during free time as there always has been in the after-school leisure program. “One does as one always did, but call it teaching (R.3)”. Activities and teaching are synonymous during the free time. With the school mission, the curriculum and pre-planned, structured activities are at the center, but here there is room for spontaneous initiatives.

When newly graduated teachers from the education program start teaching in the after-school leisure centers, utilizing the school syllabi then, “it is easy to lose the leisure-time pedagogy (R.2)”, says one respondent. There was room to use one’s own competencies that were not always strongly connected to subjects, but were well suited for complementary activities. “School subjects now get more and more space and absorb all the time. If one is not certified to teach a subject, one must become more of an extra resource in the traditional work of the school (R.4)”, says one respondent.

4.6. A Performative Position

Even when talking about education and teaching, many try to maintain the after-school leisure program pedagogy with its complementary and compensatory mission more directed towards social and group interaction. The image projected in documentation and evaluations is concentrated on the assignment more directed toward the school, but that might not correspond to the largest time segment of the program, namely, “the free time”. A leisure center teacher expressed this as, “We try to show our new mission, but work quite a lot as we always have though the conditions to do that job have worsened now (R.3)”.

4.7. Children with Special Needs

Children that are defined as needing special support/special education in school are not always perceived to need it in the after-school leisure program. Many times, the children have difficulty in achieving the set school learning goals, and then they channel their frustration by being agitated or loud. It is rare to consider a child in need of special support in the after-school leisure program, but not in school. Such a case would be when a child needs the structure, he/she would have had in a classroom.

4.8. Contact with the Special Educator

Rarely does a leisure center contact a special educator for consultation regarding the voluntary leisure program activities. If this happens, then the requested support is often focused on the child’s disability and any aids. Staff seldom ask advice about how group-oriented and inclusive initiatives should be implemented. None of the respondents know any special educator who works only in an after-school leisure program. In cases where a special educator’s help is requested, support comes from the preschool or school connected to the leisure program.

4.9. Segregating Measures

Some children must be safeguarded from the large groups now characterizing after-school leisure centers where it is common with groups of 30 to 60 children. Children with cognitive difficulties, who need a lot of adult support and have difficulty handling stimulation in a flexible setting, are usually in the special school program; therefore, a special after-school leisure program is often set up for this group. All of the respondents are of the opinion that the segregated after-school leisure programs for special school pupils have increased. “It feels as if the special school is completely by itself (R.2)”. Another commented, “An after-school leisure center where there are only children with special needs can by definition be a program conducted with special education leisure program pedagogy (R.1)”.

4.10. Compulsory and Further Education

The respondents believe the current teacher education for compulsory school has an inclusive orientation. Students study 7.5 higher education credits in special education, together with other teacher education programs. Many students express a desire for more time to deepen their knowledge regarding different types of functional disabilities; these are the wishes also expressed for further education. Many after-school leisure program educators see themselves as representing and defending vulnerable children; therefore, they want to gain more knowledge in the area.

4.11. Relevance of a More Comprehensive Study

The respondents think that there is every reason to continue with a further study as the after-school leisure program is undergoing marked change. Perhaps the definition of special education can also lead to other concepts, such as after-school leisure program pedagogy, complementing, compensating, and teaching, becoming more clearly defined. Some respondents saw the value of interviewing special educators to obtain their views on the after-school leisure special educational activities.

5. Discussion

The goals of the after-school leisure program, the preschool and the school are not only about equipping children in the sense of traditional knowledge requirements and skills, but also regarding fostering citizens in solidarity and empathy [3]. The complementary activities of the after-school leisure program have worked toward the latter, more value-related mission, but this goal has been weakened, as confirmed in the interviews. One explanation is that the after-school program has adapted to the goals and conditions of the compulsory school, where children’s differences are often dealt with through individually compensatory and/or separate measures [37]. Another reason the after-school leisure program has become less inclusive may be that the compulsory school is more valued and prioritized in the allocation of municipal resources [11]. A concrete example is when teachers in the after-school leisure program act as qualified pupil assistants in the compulsory school; that same resource is usually absent from the after-school program. The after-school leisure program pedagogy and mission are devalued by losing the position and worth in comparison with the compulsory school.

Complementing and compensating the more traditional subject focus of the school by offering the “wide pedagogy” (Figure 1) has previously been a sign of the after-school leisure program. This aspect of compensating for the environment is now at risk of being lost, when the after-school leisure program is expected to work more in order to compensate and complement a traditionally school-oriented program.

The expectations put on after-school leisure program teachers appear to be conflicting. The staff should steer and guide towards common values, those that are obviously in the wide approach; while, at the same time, they should strive for children to develop specific subject-related skills that distinguish the narrow approach (Figure 2). Thus, the staff mission is to homogenize at the same time they open for heterogeneity. This is a delicate task, and now that the after-school leisure program gains a stronger foothold in the school program, larger groups of children will probably homogenize and the narrow orientation will dominate. There are strong indications of the special after-school leisure programs continuing to increase. Unfortunately, there are no current statistics, but previous research has verified this trend [7]. Producing exact data is a task for future research that is based on this pilot study.

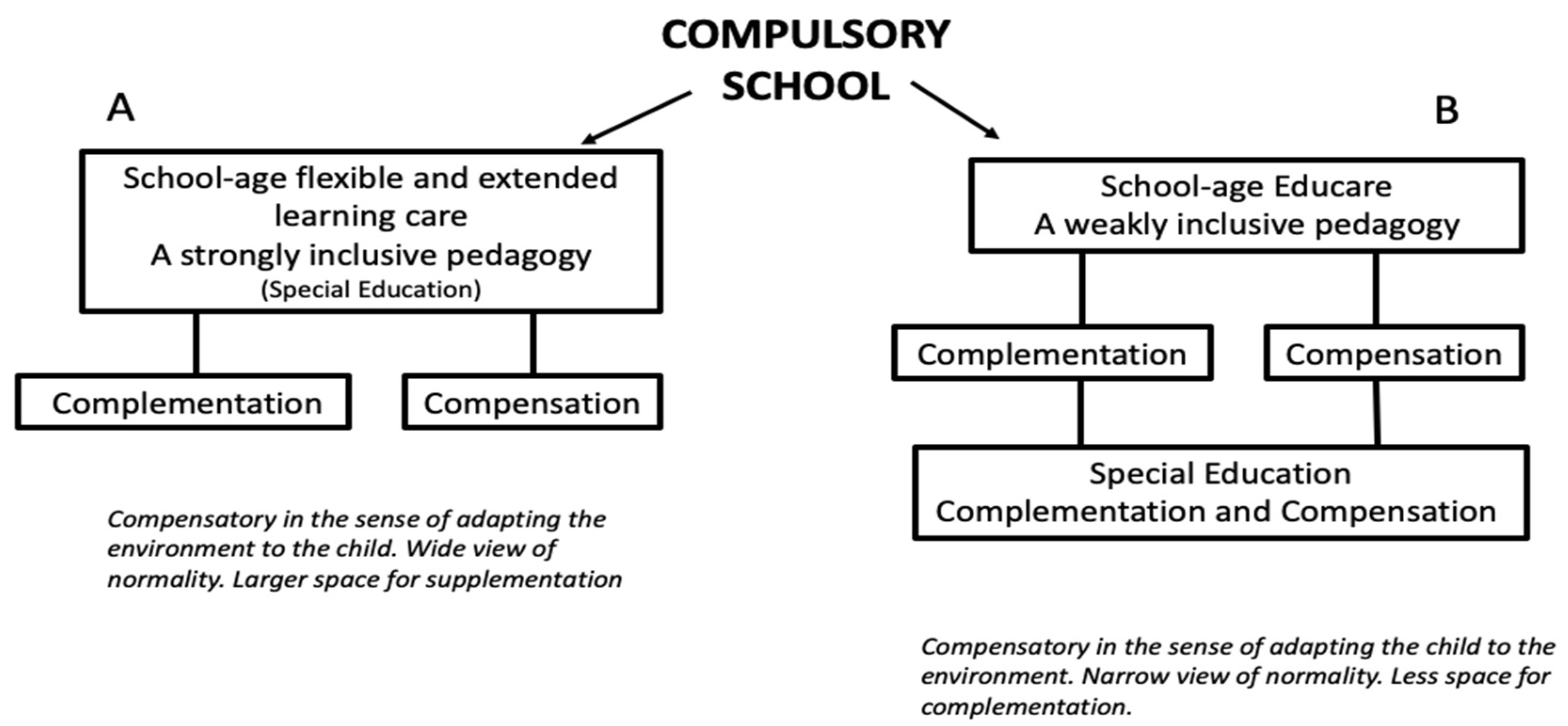

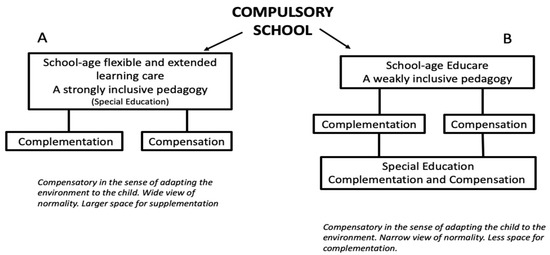

It is possible that previously the after-school leisure program pedagogy could be defined as inclusive special education that is able to accommodate all children in complementary and compensatory activities without separate and special measures (Figure 3, part A). With the mission now becoming narrower, an additional level of special after-school leisure programs has developed (Figure 3, part B). In this new program, the pedagogy cannot meet the wide approach, because basic conditions are missing. A special program all too often has strong features of the narrow approach, and there is evident risk of stigmatizing effects [35,36].

Figure 3.

Two ways to define special education in the Swedish school-age childcare.

Unlike the compulsory school, there is fairly abundant space for interpreting the teaching mission in the after-school leisure program; therefore, it is critical for all staff to discuss and take a position on the view of knowledge upon which to base their work. A position holds the basic values of the educators’ attitudes and actions, thus naturally having great influence on the program [34,36]. When considering that the after-school leisure program and the compulsory school are now united in the same School Law [4], there is every reason to safeguard the part of the after-school leisure program that has stood for unique complementary and compensatory activity in the collaboration with the school. It is important to defend the pedagogy that can complement the compulsory school’s traditional view of goals, methods, and knowledge. Compensating for differences that arise in and between schools does not mean that one necessarily needs to teach and evaluate skills the way that the school traditionally does. Compensation must not become pure support in this tradition.

Two different systems can possibly be combined in one mission. However, for educators firmly rooted in either approach, it can certainly be difficult to unite the narrow and the wide perspective in their pedagogical work. A more precise definition of the concept of teaching in a leisure center may be helpful to make the after-school leisure program pedagogy clearer. The basic view of the complementary and compensatory activities must also be clarified.

The present study is a minor qualitative pilot study, which has clear limitations, and it will not be possible to generalize. Hopefully, the result will form the basis for an extended study and, in the long run, educational material for undergraduate and further education. It is important that the leisure staff reflect and discuss what they define to be special education. The basic pedagogical view that forms the basis of the two figures can probably have some international validity. Hopefully, one can benefit from the basic construction that is presented and after some adjustments use it for analysis of the school childcare that is conducted in other countries.

Funding

This research received no external funding but was funded within the budgets of Linnaeus University.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Unesco. The Salamanca Statement and Framework for Action. On Special Needs Education; Unesco: Paris, UK, 1994; Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000098427 (accessed on 27 November 2019).

- SFS 2011:185. Skolförordning; Utbildningsdepartementet: Stockholm, Sweden, 2011.

- Skolverket. Läroplan för Grundskolan, Förskoleklassen och fritidshemmet; Skolverket: Stockholm, Sweden, 2019.

- SFS 2010:800. Skollag; Utbildningsdepartementet: Stockholm, Sweden, 2010.

- Skolinspektionen. Kvalitet i Fritidshem; Rapport 2010:3; Kvalitetsgranskning: Stockholm, Sweden, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Hansen, M. Yrkeskulturer i Möte, Läraren, Fritidspedagogen och Samverkan; Acta Universitatis: Göteborg, Sweden, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Karlsudd, P. School-age care, an ideological contradiction. Probl. Educ. 21st Century 2012, 48, 45–51. [Google Scholar]

- Dahl, M. Fritidspedagogers Handlingsrepertoar. Pedagogiskt Arbete med Barns olika Relationer; Linnaeus University Press: Växjö, Sweden, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Nilholm, C.; Persson, B.; Hjerm, M.; Runesson, S. Kommuners Arbete med Elever i Behov av Särskilt Stöd—En Enkätundersökning; INSIKT 2007:2; Vetenskapliga Rapporter från Högskolan för Lärande och Kommunikation: Jönköping, Sweden, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- SOU. 1991:54. Skola—Skolbarnsomsorg, en Helhet; Slutbetänkande av skolbamsomsorgs-kommitten; Allmänna Förlaget: Stockholm, Sweden, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Skolverket. Fritidshemmet: Lärande i Samspel Med Skolan; Skolverket: Stockholm, Sweden, 2011.

- SOU. 2020:34. Stärkt Kvalitet och Likvärdighet i Fritidshem och Pedagogisk Omsorg. Betänkande av Utredningen om Fritidshem och Pedagogisk Omsorg; Utbildningsdepartementet: Stockholm, Sweden, 2020.

- Skolinspektionen. Undervisning i Fritidshemmet; Skolinspektionen: Stockholm, Sweden, 2018.

- Saar, T.; Löfdahl, A.; Hjalmarsson, M. Kunskapsmöjligheter i svenska fritidshem. Nord. Barnhageforskning 2012, 5, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, B. Vad händer med fritidspedagogyrket och fritidshemspedagogiken i sverige? Barn 2014, 32, 61–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haglund, B. Fritidshemmets vardagspraktik. Educare 2016, 1, 64–85. [Google Scholar]

- Holmberg, L. Konsten att Producera Lärande Demokrater; Stockholms Universitet: Stockholm, Sweden, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Närvänen, A.L.; Elvstrand, H. På väg att (om)skapa fritidshemskulturer: Om visioner, gränsdragningar och identitetsarbete. Barn 2014, 32, 9–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haglund, B.; Boström, L. Everyday practices in Swedish school-age educare centres: A reproduction of subordination and difficulty in fulfilling their mission. Early Child Dev. Care 2020, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ludvigsson, A.; Falkner, C. Fritidshem—Ett Gränsland I Utbildningslandskapet. Nord. Tidsskr. Pedagog. Krit. 2019, 5, 13–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perselli, A.K.; Hörnell, A. Fritidspedagogers förståelse av det kompletterande uppdraget. Barn 2019, 37, 63–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skolverket. Fritidshemmet: Ett Kommentarmaterial till Läroplanens Fjärde del; Skolverket: Stockholm, Sweden, 2016.

- Skolverket. Fritidshem: Skolverkets Allmänna råd med Kommentarer; Skolverket: Stockholm, Sweden, 2014.

- Hammarberg, L. Att Planera för Barn och Elever med Funktionsnedsättning: En Sammanställning av Forskning, Utvärdering och Inspektion 1994–2014; Skolverket: Stockholm, Sweden, 2015.

- Markström, A.-M. Förskolan som Normaliseringspraktik: En Etnografisk Studie; Linköpings Universitet: Linköping, Sweden, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Dahlberg, G.; Moss, P.; Pence, A. Från Kvalitet till Meningsskapande: Postmoderna Perspektiv—Exemplet Förskolan, 3rd ed.; Liber: Stockholm, Sweden, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Dolk, K. Bångstyriga Barn: Makt, Normer och Delaktighet i Förskolan; Stockholms Universitet: Stockholm, Sweden, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Palla, L. Med Blicken på Barnet: Om Olikheter Inom Förskolan som Diskursiv Praktik; Lunds Universitet: Malmö, Sweden, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Hjörne, E.; Säljö, R. Att Platsa i en skOla för Alla. Elevhälsa och Förhandling om Normalitet i den Svenska Skolan; Norstedts: Stockholm, Sweden, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Skolverket. Vad Påverkar Resultaten i Svensk Grundskola? Kunskapsöversikt om Betydelsen av Olika Faktorer; Skolverket: Stockholm, Sweden, 2009.

- Skolinspektionen. Särskolan. Granskning av Handläggning och Utredning inför Beslut om Mottagande; Skolinspektionen: Stockholm, Sweden, 2011.

- Lundbäck, B.; Fälth, L. Leisure-time activities including children with special needs: A research overview. Int. J. Res. Ext. Educ. 2019, 7, 20–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karlsudd, P. Tillsammans. Integreringens Möjligheter och Villkor; Högskolan: Kalmar, Sweden, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Persson, B.; Persson, E. Inkludering och Måluppfyllelse- att nå Framgång med Alla Elever; Liber AB: Stockholm, Sweden, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Darling-Hammond, L.; Bransford, J. Preparing Teachers for a Changing World: What Teachers should Learn and be Able to Do; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Hattie, J. Visible Learning: A Synthesis of over 800 Meta-Analyses Relating to Achievement; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karlsudd, P. The Search for Successful Inclusion. Disabil. CBR Incl. Dev. 2017, 28, 142–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Ackesjö, H.; Nordänger, U.K.; Lindqvist, P. Att jag kallar mig själv för lärare i fritidshem uppfattar jag skapar en viss provokation.” Om de nya grundlärarna med inriktning mot fritidshem. Educare 2016, 1, 86–109. [Google Scholar]

- Patel, R.; Davidson, B. Forskningsmetodikens Grunder. Att Planera, Genomföra och Rapportera en Undersökning; Studentlitteratur: Lund, Sweden, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Elever och Personal I Fritidshem Läsåret 2018/19; PM: Skolverket, Sweden, 2019; Available online: https://www.skolverket.se/publikationsserier/beskrivande-statistik/2019/pm---elever-och-personal-i-fritidshem-lasaret-2018-19 (accessed on 28 November 2020).

- Vetenskapsrådet. God Sed i Forskningen; Vetenskapsrådet: Stockholm, Sweden, 2017.

- Kvale, S. Den Kvalitativa Forskningsintervjun; Studentlitteratur: Lund, Sweden, 1997. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).