The Development of an Educational Outdoor Adventure Mobile App

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Location Based Games

- The ability to adjust the level of fitness required, by carefully selecting the location of the treasure/geocache.

- Development of the sense of orientation.

- The process of exploration gives a high level of interest.

- The challenge and the subsequent feeling of success when a treasure is found, psychologically benefits the participantThe social skills that can be acquired.

- The pleasant feeling of achieving a goal. In particular, students that are not very successful in sports can build in this way their self-esteem.

- When participants are separated in groups, the sense of togetherness, as a target of a group with a common purpose.

- Socialization with other participants.

- Develops the cohesion and the collaboration of a group, along with the encouragement of communication.

1.2. Smartphone Use Educational Challenges

1.3. Motivation and Research Aim

2. Methodology

2.1. Researching Teachers’ Skills and Perceptions

2.1.1. Participants

2.1.2. Research Tools

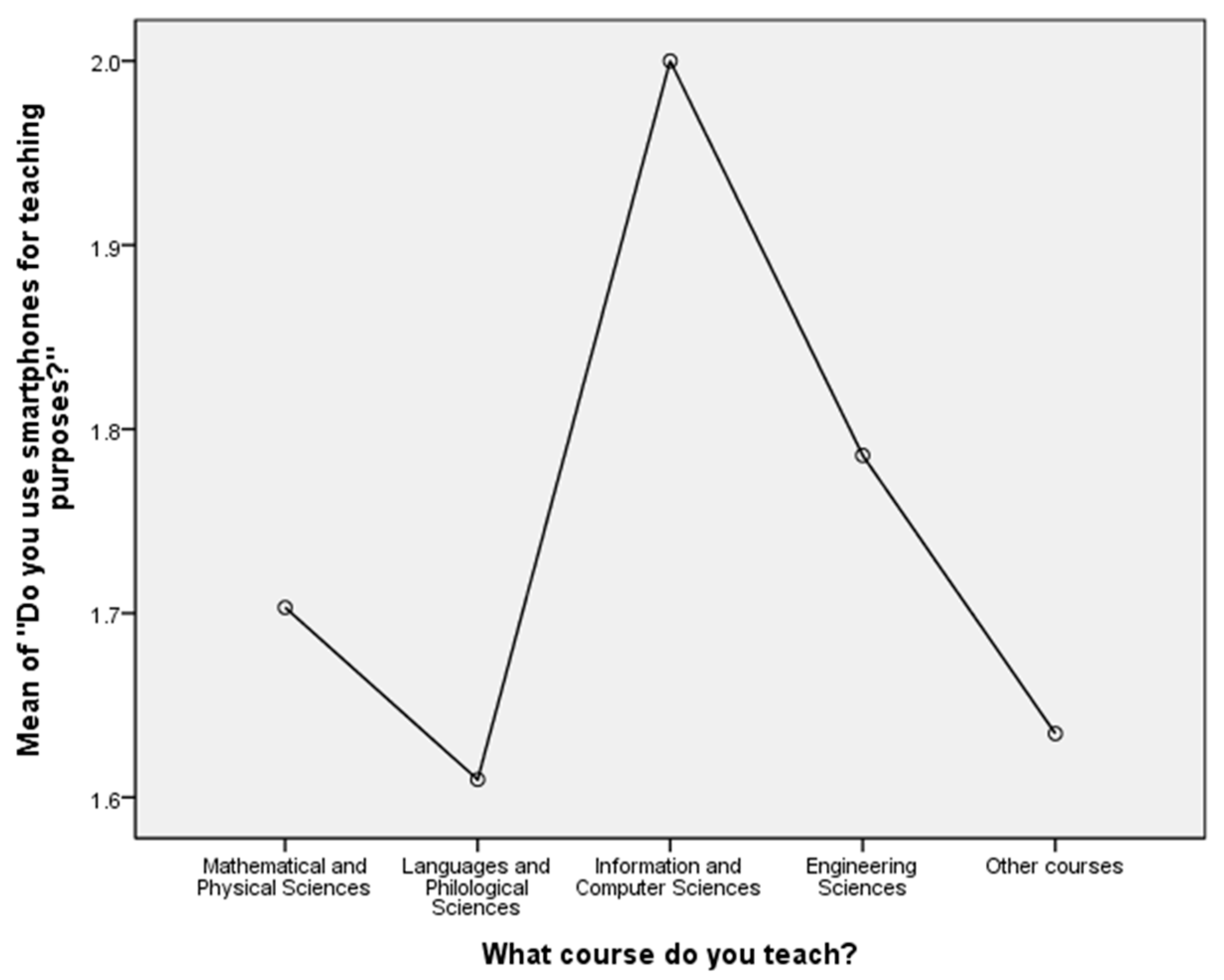

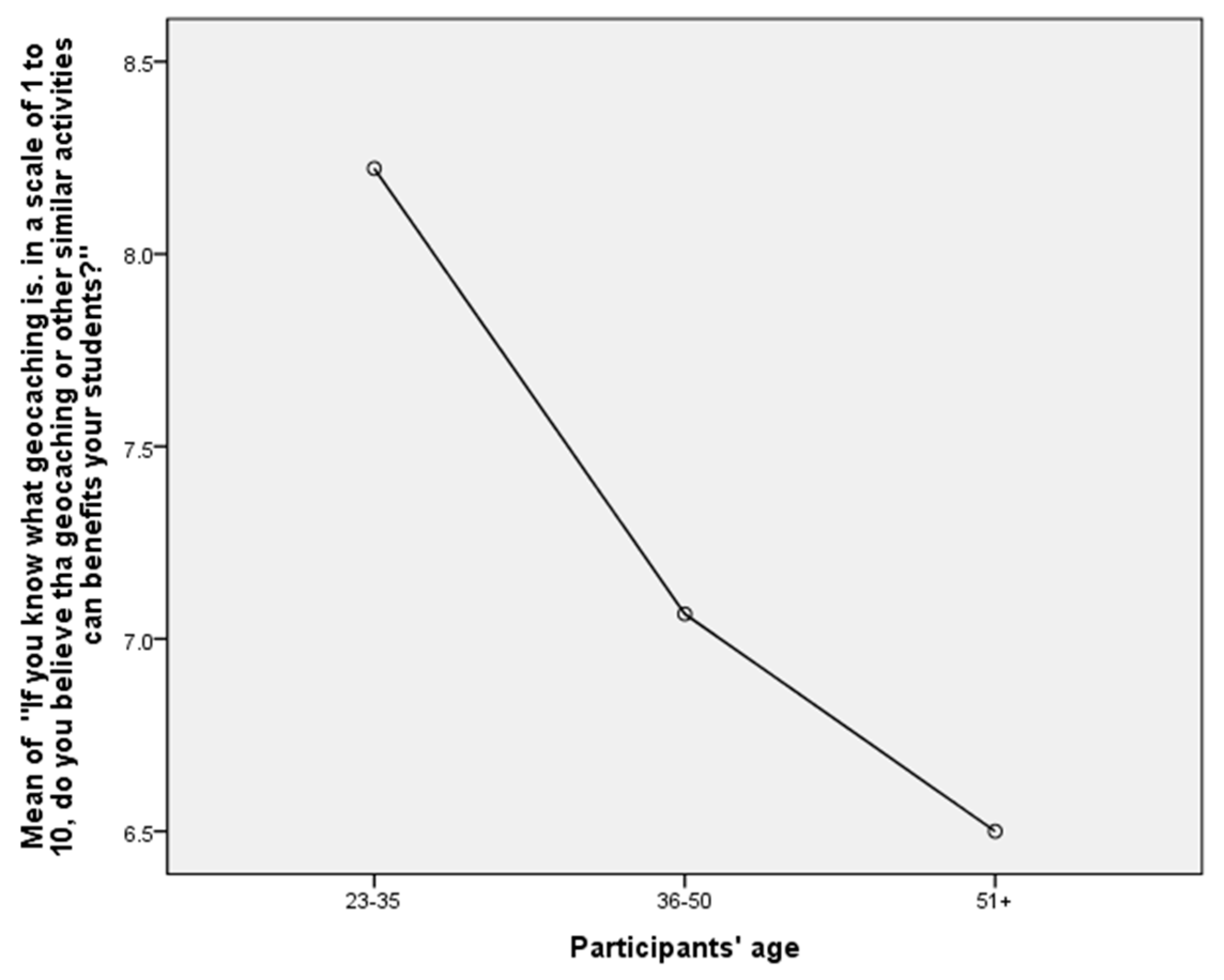

2.1.3. Results

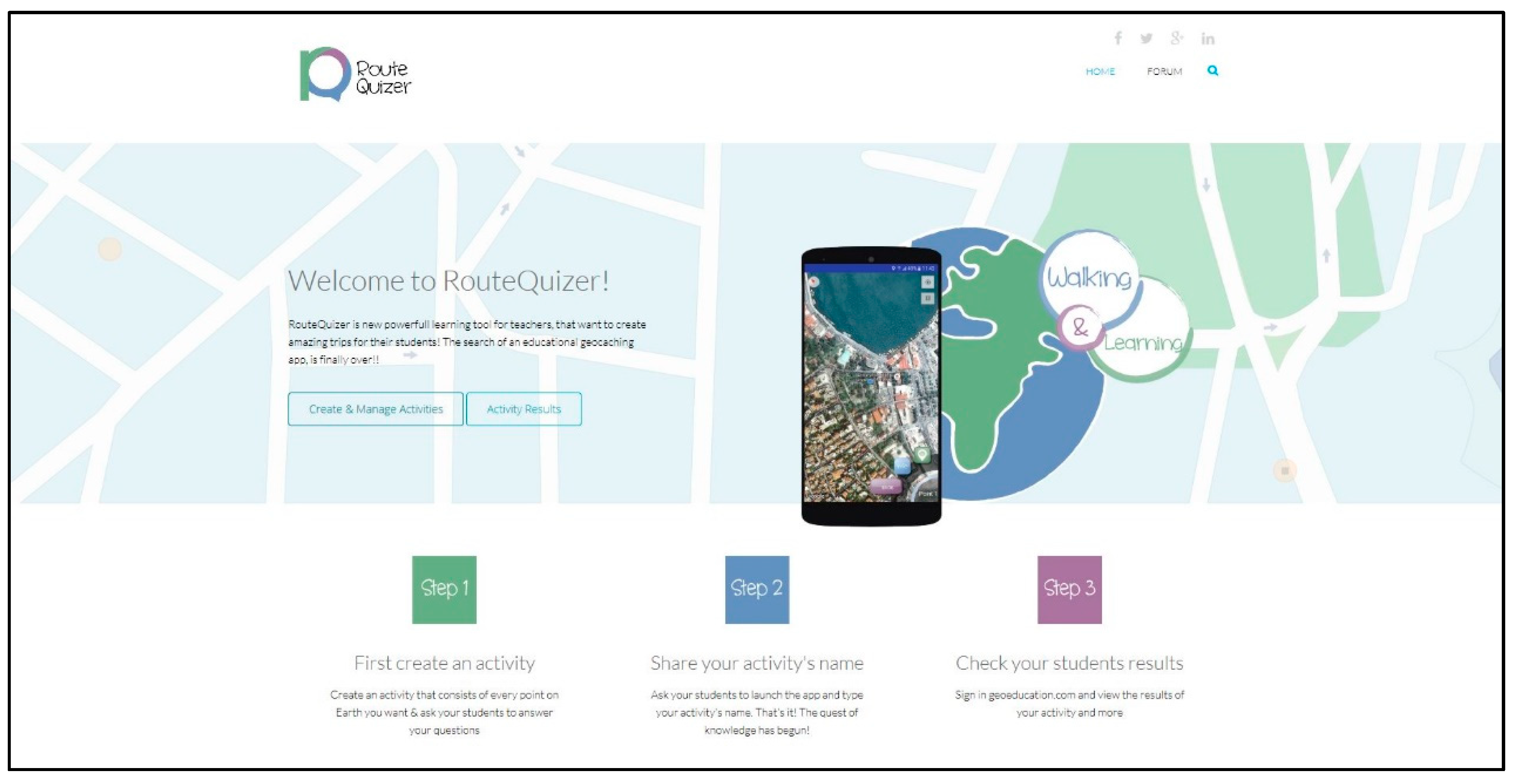

2.2. The RouteQuizer Prototype

2.2.1. Requirements

- The mobile application should be Android OS compatible.

- The system should be simple to use.

- The system should provide effective learning outcomes

2.2.2. The Web Application

2.2.3. Creating and Managing Activities

- Code. The tutor defines the “Activity Name”.

- Point Order. The tutor enters the order in which each point will appear to students. In each new activity that a tutor creates, the first point must have the point order value of 1, the second a value of 2, and so on. In this way the teacher can largely control the route that the students will follow, during the use of the activity.

- Latitude. In this field, he enters the first part of the coordinates, i.e., latitude.

- Longitude. In this field, he enters the second part of the coordinates, i.e., longitude.

- Information. Information about the point to be visited.

- Question. The question to be displayed to the students as soon as they arrive at the point.

- Answer 1. The first possible answer.

- Answer 2. The second possible answer.

- Answer 3. The third possible answer.

- Answer 4. The fourth possible answer.

- Right Answer. The tutor provides the right answer.

- Distance. This field is filled by a number, corresponding to the maximum distance in meters, in which the students must approach, for the question to be displayed.

2.2.4. Browsing the Results of an Activity

- UserContains the student’s username.

- Activity name

- Point1 in case it was the first visited point, 2 if it was the second etc.

- ResultContains either “Correct” or “Wrong”.

- HelpContains either “Used Help” or “Did not use help”, that indicates whether the user used the help button or not.

- Date and TimeThe date and time when the students answered the question.

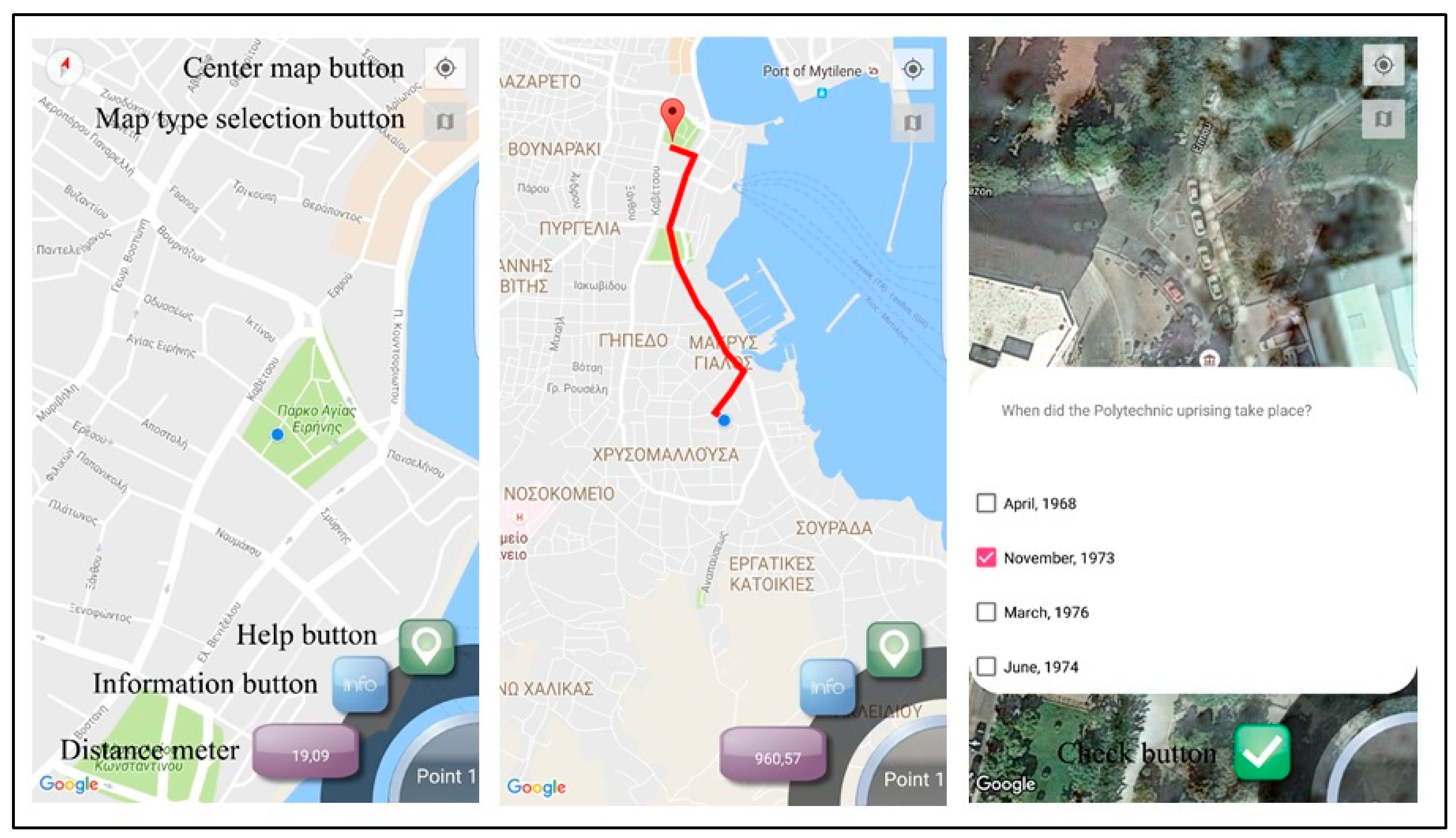

2.2.5. The Mobile Application

- Only authorized users that know the activity’s name can have access.

- It ensures the uniqueness of each activity.

- Sharing the same activity with other teachers, is easy, simply by sharing its name.

- The application, as is, is usable by different teachers and for different classes.

- The teacher can easily disable an activity if he wants to, by changing its title.

2.2.6. Main Screen

- Center map button.Upon selection, the screen is centered in the user’s position.

- Map type selection button.The user can choose between four different map types, a road map, a satellite map, terrain map and a hybrid map.

- Help button.A red marker indicating the position of the destination, as well as the shortest route to get there, appear on the screen, preventing the user from getting lost. Also, the tutor is informed whether the help button has been used or not.

- Information button.A window containing all the information provided by the tutor appears, helping the user locate the destination point but also to get informed about it. In case the text is long, the window contains a scroll bar.

- Distance meter.The distance meter represents the distance in meters between the user and the destination. That way, the user knows whether he is heading to the right direction or not.

2.3. Students’ Evaluation—Pilot Case Study

- how the application performed technically,

- the students’ spontaneous comments, and

- the student’s behavior and concentration during the activity.

2.4. Teachers’ Evaluation—Teacher Training Program

- Web application:

- The location of the points should be selected on a map.

- Open ended questions should also be supported.

- Teachers should be able to copy an activity they have created and just change the order of the points.

- Mobile application:

- The information window should not only contain text, but also photos, videos, and sound recordings.

- Help button should not be easily used. A confirmation window should also appear.

2.5. Case Studies

2.5.1. Case Study no1—First Junior High School

2.5.2. Case Study no2—University of the Aegean Geography Students

2.5.3. Case Study no3—Mantamados Junior High School Students

2.5.4. Case Study no4—Dyslexic Junior High School Students

3. Results

- How much did you enjoy the treasure hunt experience?

- Would you like to repeat such an activity in the future?

- Not all students of the first group were paying attention,

- The application encouraged collaborative learning

- No questions were left unanswered while using the mobile application.

4. Discussion

- Students should work in groups.That way students develop their social skills (sense of togetherness, socialization, development of the cohesion and the collaboration of the group, encouragement of communication). At the same time, the number of devices needed is significantly decrease, resulting to a huge cost saving in case the devices are provided by the school.

- Schools should provide the devices to be used.The cost of a “low-end” android smartphone ranges from 50USD to 100USD a cost that would not significantly affect the yearly budget of an education institute/school. The students will not be required to either own an android smartphone or bring their device to school, something that possibly could also be banned in many schools. In addition, the students will be using the device only for as long as the activity lasts and will all be using the same device type encouraging equality and avoiding digital exclusion.

- Smartphone devices should be “locked”.In the occasion the school provides the mobile devices we suggest all other applications and features of the device to be locked, meaning that the only application accessible to students will be RouteQuizer. This ensures that students will not get distracted by other applications installed in the device such as camera, web browser, etc. Technically, this can be easily achieved by using one of many free applications available on Google Play that enable users to hide all applications installed in a device.

- Teachers must ensure the activity is conducted safely.Although RouteQuizer provides all possible functions to prevent students from getting lost, it is the teacher’s sole responsibility to ensure the safe conduct of the activity. We recommend that activities should take place in a controlled environment, especially in the occasion the students are children.

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Scrutton, R. Outdoor adventure education for children in Scotland: Quantifying the benefits. J. Adventure Educ. Outdoor Learn. 2014, 15, 123–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richmond, D.; Sibthorp, J.; Gookin, J.; Annarella, S.; Ferri, S. Complementing classroom learning through outdoor adventure education: Out-of-school-time experiences that make a difference. J. Adventure Educ. Outdoor Learn. 2018, 18, 36–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, J.K.; Kremer, D.; Pebworth, K.; Werner, P. Introduction to Geocaching. In Geocaching for Schools and Communities; Kassing, G., Vallese, R., Campbell, D., Evans, E., Connolly, P., Eds.; Human Kinetics: Champaign, IL, USA, 2010; pp. 17–20. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Kandari, Y.Y.; Al-Sejari, M.M. Social isolation, social support and their relationship with smartphone addiction. Inf. Commun. Soc. 2020, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDaniel, B.T.; Coyne, S.M. “Technoference”: The interference of technology in couple relationships and implications for women’s personal and relational well-being. Psychol. Popul. Media Cult. 2016, 5, 85–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boumosleh, J.M.; Jaalouk, D. Depression, anxiety, and smartphone addiction in university students—A cross sectional study. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0182239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Avouris, N.; Yiannoutsou, N. A Review of Mobile Location-based Games for Learning across Physical and Virtual Spaces. J. Univers. Comput. Sci. 2012, 18, 2120–2142. [Google Scholar]

- Leblanc, A.G.; Chaput, J.-P. Pokémon Go: A game changer for the physical inactivity crisis? Prev. Med. 2017, 101, 235–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GPS.gov. Available online: https://www.gps.gov/systems/gps/modernization/sa/ (accessed on 15 August 2020).

- Ihamaki, P.J. Geocaching: Interactive Communication Channels Around the Game. Eludamos J. Comput. Game Cult. 2012, 6, 133–152. [Google Scholar]

- Jacob, S.M.; Issac, B. The Mobile Devices and its Mobile Learning Usage Analysis. In Proceedings of the International Multi Conference of Engineers and Computer Scientists, Hong Kong, China, 19–21 March 2008; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Dochev, D.; Hristov, I. Mobile Learning Applications—Ubiquitous Characteristics and Technological Solutions. Cybern. Inf. Technol. 2006, 6, 63–74. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, P.K.; Mahdavi, J.; Carvalho, M.; Fisher, S.; Russell, S.; Tippett, N. Cyberbullying: Its nature and impact in secondary school pupils. J. Child. Psychol. Psychiatry 2008, 49, 376–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nalliah, R.P.; Allareddy, V. Students distracted by electronic devices perform at the same level as those who are focused on the lecture. PeerJ 2014, 2, e572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kautiainen, S.; Koivusilta, L.; Lintonen, T.; Virtanen, S.M.; Rimpelä, A. Use of information and communication technology and prevalence of overweight and obesity among adolescents. Int. J. Obes. 2005, 29, 925–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadiku, M.N.O.; Shadare, A.E.; Dada, E.; Musa, S.M. Digital Divide. J. Multidiscip. Eng. Sci. Technol. 2016, 3, 10. [Google Scholar]

- Dakich, E. Teachers’ ICT Literacy in the Contemporary Primary Classroom: Transposing the Discourse. In Proceedings of the AARE Annual Conference, Parramatta Campus, Australia, 27 November–1 December 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Sharples, M. Mobile learning: Research, practice and challenges. Distance Educ. China 2013, 3, 5–11. [Google Scholar]

- Kaimara, P.; Poylimenou, S.M.; Oikonomou, A.; Deliyannis, I.; Plerou, A. Smartphones at Schools? Yes, Why not? EJERS. Spec. Issue CIE 2018, 2018, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michalakis, V.I.; Vaitis, M.; Klonari, A. The ICT Literacy Skills of Secondary Education Teachers in Greece. In Proceedings of the 11th International Conference on Computer Supported Education CSEDU 2019, Herakleion, Greece, 2–4 May 2019; Volume 2, pp. 376–383. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez, P.; José, C.; Olmos, M.; Peñalvo, S.G.; Francisco, J. Understanding mobile learning: Devices, pedagogical implications and research lines. Teoría Educ. Educ. Cult. Soc. Inf. 2014, 15, 20–42. Available online: https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/2010/201030471003.pdf (accessed on 2 September 2020).

- Bolliger, D.; McCoy, D.; Kilty, T.; Shepherd, C.E. Smartphone use in outdoor education: A question of activity progression and place. J. Adventure Educ. Outdoor Learn. 2020, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shultis, J. The impact of technology on the wilderness experience: A review of common themes and approaches in three bodies of literature. In Wilderness Visitor Experiences: Progress in Research and Management; RMRS-P-66; Cole, D.N., Ed.; U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station: Fort Collins, CO, USA, 2011; pp. 110–118. [Google Scholar]

- Dickson, T.J. If the outcome is predictable, is it an adventure? Being in, not barricaded from, the outdoors. World Leis. J. 2004, 46, 48–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolliger, D.; Shepherd, C.E. Instructor and adult learner perceptions of the use of Internet-enabled devices in residential outdoor education programs. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 2016, 49, 78–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, H.-C.; Chang, C.-Y.; Wen-Shiane, L.; Fan, Y.-L.; Wu, Y.-T. The implementation of mobile learning in outdoor education: Application of QR codes. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 2013, 44, E57–E62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsien-Sheng, H.; Chih-Cheng, L.; Ruei-Ting, F.; Kun Jing, L. Location Based Services for Outdoor Ecological Learning System: Design and Implementation. J. Educ. Technol. Soc. 2010, 13, 98–111. [Google Scholar]

- Kohen-Vacs, D.; Ronen, M.; Cohen, S. Mobile Treasure Hunt Games for Outdoor Learning. Bull. IEEE Tech. Comm. Learn. Technol. 2012, 14, 24–26. [Google Scholar]

- Giemza, A.; Ulrich Hoppe, H. Mobilogue—A Tool for Creating and Conducting Mobile Supported Field Trips. In Proceedings of the 12th World Conference on Mobile and Contextual Learning (mLearn 2013), Doha, Qatar, 22–24 October 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Vithani, T.; Kumar, A. Modeling the Mobile Application Development Lifecycle. In Proceedings of the International Multi Conference of Engineers and Computer Scientists, Hong Kong, China, 12–14 March 2014; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, A.; Ahmad, S.; Ehsan, N.; Mirza, E.; Sarwar, S.Z. Agile software development: Impact on productivity and quality. In Proceedings of the 2010 IEEE International Conference on Management of Innovation & Technology, Singapore, 2–5 June 2010; pp. 287–291. [Google Scholar]

- Meishar-Tal, H.; Ronen, M. Experiencing a Mobile Game and Its Impact on Teachers’ Attitudes towards Mobile Learning. In Proceedings of the International Association for Development of the Information Society (IADIS) International Conference on Mobile Learning, Algarve, Portugal, 9–11 April 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Mac Callum, K.; Jeffrey, L. Comparing the role of ICT literacy and anxiety in the adoption of mobile learning. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2014, 39, 8–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scherer, R.; Siddiq, F.; Teo, T. Becoming more specific: Measuring and modeling teachers’ perceived usefulness of ICT in the context of teaching and learning. Comput. Educ. 2015, 88, 202–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Bannon, B.W.; Thomas, K. Teacher perceptions of using mobile phones in the classroom: Age matters! Comput. Educ. 2014, 74, 15–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michalakis, V.I.; Vaitis, M.; Kizos, A. Geocaching and Mobile Learning in Geographic Education: A System and a Case Study. In Proceedings of the 11th International Conference of the Hellenic Geographical Society, Lavrion, Greece, 12–15 April 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Klonari, A.I.; Passadelli, A.S. Differences between dyslexic and non-dyslexic students in the performance of spatial and geographical thinking. Rev. Int. Geogr. Educ. Online 2019, 9, 284–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Passadelli, A.S.; Michalakis, V.I.; Klonari, A.; Vaitis, M. Detecting Dyslexic Students Geospatial Abilities Using A Treasure Hunt Mobile Learning Application. In Proceedings of the 2nd Conference on “International Perspectives in Education”, Mytilene, Greece, 1–2 October 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Costabile, M.F.; De Angeli, A.; Lanzilotti, R.; Ardito, C.; Buono, P.; Pederson, T. Explore! Possibilities and Challenges of Mobile Learning. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Florence, Italy, 5–10 April 2008; pp. 145–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitale, J.L.; McCabe, M.; Tedesco, S.; Wideman-Johnston, T. Cache Me If You Can: Reflections on Geocaching from Junior/Intermediate Teacher Candidates. Int. J. Technol. Incl. Educ. 2012, 1, 2–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hellgren, J.M.; Stewart, K.; Sullivan, K.P. Student Experiences of Geocaching: Exploring Possibilities for Science Education. In Proceedings of the Nordic Research Symposium on Science Education (NFSUN): Inquiry-Based Science Education in Technology-Rich Environments, Helsinki, Finland, 4–6 June 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Aleci, C.; Piana, G.; Piccoli, M.; Bertolini, M. Developmental dyslexia and spatial relationship perception. Cortex 2012, 48, 466–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orphanou, H.M. Learning Difficulties. Teaching Notes; Department of Speech Therapy, Technological Educational Institute of Epirus: Ioannina, Greece, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Palmárová, V.; Lovászová, G. Mobile Technology used in an adventurous outdoor learning activity: A case study. Problems of Education in the 21st Century. 2012, Volume 44. Available online: http://www.scientiasocialis.lt/pec/node/files/pdf/vol44/64-71.Palmarova_Vol.44.pdf (accessed on 2 September 2020).

- Ellbrunner, H.; Barnikel, F.; Vetter, M. “Geocaching” as a method to improve not only spatial but also social skills—Results from a school project. In GI_Forum 2014—Geospatial Innovation for Society; Vogler, R., Car, A., Strobl, J., Griesebner, G., Eds.; Wichmann: Berlin, Germany, 2014; pp. 348–351. [Google Scholar]

- Adanalı, R.; Alım, M. The Views of Preservice Teachers for Problem-Based Learning Model Supported by Geocaching in Environmental Education. Rev. Int. Geogr. Educ. Online 2017, 7, 264–292. Available online: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1165606.pdf (accessed on 21 August 2020).

- Arain, A.A.; Hussain, Z.; Rizvi, W.H.; Vighio, M.S. An analysis of the influence of a mobile learning application on the learning outcomes of higher education students. Univers. Access Inf. Soc. 2017, 17, 325–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klimova, B. Impact of Mobile Learning on Students’ Achievement Results. Educ. Sci. 2019, 9, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Case Study | Participants | Number of Participants | Participants’ Age | Location | Learning Subject |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1st junior high school students | 27 | 12–15 | Surroundings of the University of the Aegean campus | Analysis and Perception of the landscape |

| 2 | University of the Aegean Geography students | 25 | 18–21 | Surroundings of the University of the Aegean campus | Analysis and Perception of the landscape |

| 3 | Mantamados junior high school students | 18 | 12–15 | Mantamados village | The village’s history |

| 4 | Dyslexic junior high school students | 12 | 12–15 | Mytilene city centre | Practising orientation skills visiting the city’s monuments |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Michalakis, V.I.; Vaitis, M.; Klonari, A. The Development of an Educational Outdoor Adventure Mobile App. Educ. Sci. 2020, 10, 382. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci10120382

Michalakis VI, Vaitis M, Klonari A. The Development of an Educational Outdoor Adventure Mobile App. Education Sciences. 2020; 10(12):382. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci10120382

Chicago/Turabian StyleMichalakis, Vyron Ignatios, Michail Vaitis, and Aikaterini Klonari. 2020. "The Development of an Educational Outdoor Adventure Mobile App" Education Sciences 10, no. 12: 382. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci10120382

APA StyleMichalakis, V. I., Vaitis, M., & Klonari, A. (2020). The Development of an Educational Outdoor Adventure Mobile App. Education Sciences, 10(12), 382. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci10120382