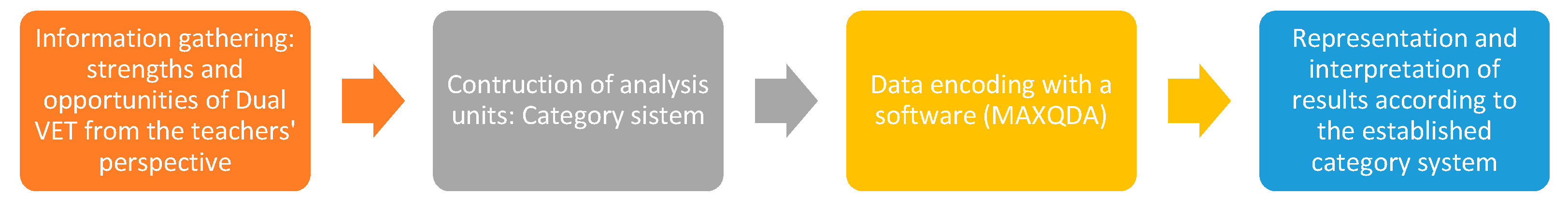

Next, we show the analyses carried out and address their interpretation, relying on the textual citations with which the participants have justified, classifying them into strengths and opportunities that condition the success of Dual VET in the Andalusian context.

5.1. Strengths

We begin with the analysis of the internal factors that, according to the respondents, are functioning as strengths for Dual VET offerings in Andalusia. Specifically, it is shown how the identified strengths are distributed in terms of percentages amongst the categories defined in the system used for said analysis (

Figure 2).

As we can see, most of the identified strengths revolve around the category “agents” (46.1% of contributions), which implies that, according to the participants in the consultation, the characteristics of the teachers and students involved in Dual VET are its strength. The “model” that supports this training modality is also a strength, with 38.6% of the contributions making reference to it. Only 8.1% and 7.2% of the contributions are associated with the characteristics of the institutions and companies respectively as generators of the strengths of Dual VET in this region.

Considering the subcategories, the following graph (

Figure 3) highlights how the subcategory “students” and within this subcategory, the unit of analysis “professional insertion” is the aspect most noted as a strength by the interviewees. Undoubtedly, an aspect closely related to the “character” and “focus” of this training model that provides “quality”. All this also motivated by the ‘teachers’ who participate in this training modality.

Breaking down the map of categories defended in the analysis procedure, and in respect to the subcategory groupings, we must point out that out of 100% of the contributions, the subcategory “students” (corresponding to the category “agents”) is the one that includes the largest number of coded comments, with a weight of 29.7%, followed by the subcategories “focus” (13.5% of the coded contributions) and ”character“ (12.4%) which, according to their percentage of presence, are those subcategories with the most associated comments within those that have to do with this ”model“ of training (

Figure 3).

The governance model and the experience of the institutions were not frequently noted as strengths (with 0.6% and 1.1% contributions respectively) (

Figure 3).

On the other hand, following a more detailed analysis, we can see the interrelationships of ideas that the participants have exposed through their contributions (

Figure 4). In this sense, and from the cluster that is exposed below, it is revealed that, in general, the interviewees indicate more than one idea in their contributions, interconnecting some strengths with others. From this cluster we can highlight how the contributions related to the “professional insertion” analysis unit are completed with other comments associated with strengths related to the “training” of the students and their “professional development” as well as ideas related to the “training model”, its “curricular focus”, the “contextualized training”, the “offers” or the learning “results”, among other units of analysis; associations that highlight the quality of dual VET in terms of results, that is, of laboral insertion.

On the other hand, it is very peculiar that there are other isolated units of analysis that are not connected with other ideas such as the “management model” (category institution), ”specialized training“ (category model) and “company/productive fabric” (category company). The comments associated with strengths linked to these units of analysis are minimal, but in themselves are relevant due to the strengths they represent. A global analysis of all the contributions has allowed us to identify that the Dual VET governance model proposed by the Educational Administration itself is the object of permanent criticism. The resources assigned by the Administration to the centres that offer Dual VET education, and the existence of Dual VET and non-Dual VET students in the same training cycle are aspects of the governance model that are cross-sectionally considered to be weaknesses by the teachers of the participating centres.

Finally, taking into account the frequency of the participants’ contributions according to the units of analysis, we must highlight that there is a strength that stands out above the others with 48 associated comments, representing 21.7% of the total contributions (

Table 7).

For almost 50% of the teachers participating in this consultation, one of the greatest strengths of Dual VET is its ability to facilitate the “professional insertion” of students with arguments such as those shown in the following graph (

Figure 5).

With a much lower frequency, but still with a certain degree of relevance, are the remaining aspects identified as strengths. We speak of the strengths linked to the other analysis units that have to do with the curricular approach (15 contributions, 6.8%) and methodological approach (12 contributions, 5.4%) of the model; with the contextualized and practical nature of the training (10 contributions, 4.5%) (11 contributions, 5%) respectively, as well as the results achieved (11 contributions, 5%), the training offering (10 contributions, 4.5%) and the collaborative relationships established between the institution and the companies (11 contributions, 5%). Training (13 contributions; 4.9%) and the motivation of the students (11 contributions, 5%), teacher training (9 contributions; 4.1%) and the active participation of companies (9 contributions, 4.1%) are other strengths that stand out from all those outlined by the participants.

These strengths are represented in the following figure by some of the contributions of the participants (

Figure 6).

In general terms, the contributions of the participants in this consultation have confirmed strengths that other studies in other contexts have shown, placing value on internal aspects that condition the success of Dual VET.

As the analysis of the contributions indicates, labour insertion is the driving strength of this modality in Andalusia. Alongside this, it is necessary to highlight other characteristics of Dual VET associated with the students that are seen as strengths, and here we refer to the enthusiasm and motivation of the students and the quality of the training that they receive, - a comprehensive and eminently practical and experiential based training; training that is accompanied by an educational model whose curricular structure and methodological approach have also been highlighted as added values:

“Most of the content has a great practical load, students learn by doing” (Centre 1. S.17).

“A new vision of Vocational Training, proving the student with the realities of work from the outset and a ‘know-how’ approach to learning” (Centre 2. S.57).

“Working in small groups is very advantageous and facilitates the students’ progress” (Centre 3. S.59).

Finally, we want to highlight an aspect that has been referred to as benefit in only two contributions and the different meaning noted in other contributions has forced us to see that it may be a “double-edged sword” -the specialised nature the formation:

“The specialization of the training of students is detrimental to the versatility that VET graduates must have and that the world of work currently needs” (Centre 2, S.77).

“It is necessary to be careful because with a very specialised training the student is prepared for entry into a specific company and for very specialised work that is often limited to just that company” (Centre 3, S.85).

Therefore, the detailed analysis of these contributions allows us to highlight how the practical and contextualised nature of Dual VET has been identified as a strength compared to its specialized nature, which has been considered as such in only two contributions. General training or specialised training is a question that has generated very interesting debates. As stated by Barrientos, Martín-Artiles, Lope and Carrasquer (2019) [

24], although it is true that specific training allows greater laboral insertion by better adapting to the needs of a company, this specialization reduces the possibilities of laboral mobility for graduates. On the other hand, one cannot lose sight of the fact that the educational system must provide general training that is easily transferable from one professional context to another, and from some companies and job positions to others within the same field. Versatility is one of the requirements of the current professional context.

5.2. Opportunities

Regarding the external factors that, according to the respondents, are providing opportunities for Dual VET in Andalusia, we should note that, although they are represented by a lower number of contributions, they are relevant and show real opportunities supported by other studies.

Specifically, it is shown (in terms of percentages) how the opportunities identified are distributed amongst the categories defined in the system used for said analysis (

Figure 7).

The previous graph (

Figure 7) identifies the three main dimensions from which the most outstanding opportunities associated with Dual VET are projected. The “productive context” category is one that brings together most of the identified opportunities (64.3% of the contributions), which implies that, according to the participants in the consultation, the business and productive fabric is the great external ally that is helping increase the success of this training modality. 28.6% of the contributions of the participants revolve around the “social context” highlighting the dissemination and social recognition of this training modality as an external aspect that is conditioning the success of Dual VET. Finally, with 7.1% of the contributions, the participants consider that the “political context” is also an external factor conditioning said success.

The cluster shown in the following figure (

Figure 8) shows that there are three subcategories from amongst those that have been identified that the participants have interconnected in their comments, and that have to do with the “Qualification” and the “Recruitment” of future workers by part of the business fabric, and in turn both opportunities correlate, through the comments of the participants, with the category of social ”Recognition“ that this training modality is achieving.

Finally, taking into account the frequency of the contributions of the participants according to the subcategories of analysis, highlights how within the “productive context” category, the “Qualification” and ”Recruitment“ subcategories are the two aspects most seen as opportunities by the interviewees. This is undoubtedly an aspect that contributes “recognition” to this training modality in the “social context” at the same time as it increases ”interest“ as a result of the ”political context“. There is a circumstance external to the dual training model and within the productive context that provides a great opportunity to said model—we refer to the need of the productive and business context to have qualified workers (30.9%) (

Figure 9).

The analysis of the contributions made by the teachers in this enquiry, position the opportunities of this VET modality in the productive context. The most common arguments that justify this consideration underline that the training received by the student of this VET modality in the companies, qualifies them as future workers of those companies. The companies are not only providing competitive training to develop their task in the specific workplace, but also training them into the own culture of the company.

In a close relationship with the previous arguments, some others emphasize the fact that with this VET modality, the companies recruit workers and tackle their generational replacement without the repercussion in their productive ability nor the quality of their products (“recruitment”—19.2% of the contributions). The remainder arguments that those teachers, that replied to the survey, used to justify these opportunities for Dual VET in the productive context can be grouped in three different groups: (1) arguments based on the increasing social recognition of this formative modality and its great dissemination and attention from the business organizers and foundations with high prestige as “Fundación Bertelsmann” (“recognition” with the 19.2% of the contribution and “diffusion” with the 1.5%); (2) other arguments are based on the interest of the productive system in their correlation with the educational system, between other reasons, for the contemplation in the training of the competencies of professional action required in the working context (“coordination” with the 7.7% of the contributions); (3) arguments that highlight the fact of the great opportunity that is considered the use of the VET modality in the Andalusian politics (“interest” with the 7.7% of the contributions). Finally, and outside these groups, we want to highlight, although with a very low incidence and relevance (3.8% of contributions), the allusion that some of the participants have made to the technological transformations that the 4.0 revolution is generating in the national productive context and slowly into in Andalusian context, and how they represent an opportunity that VET in general and Dual VET in particular should not miss. A global analysis of all the contributions in this section has allowed us to confirm that the interest of companies in this training modality lies in the possibility that it offers a company to hire future workers trained according to the needs and culture of their companies, and thus to reduce the costs of on-boarding new staff. However, and in a transversal way, reference is also made to the numerous obstacles for the implementation of the dual VET scheme, which have to do with the productive and business context: a lack of incentives for SMEs and micro-enterprises to ensure their involvement in Dual VET, a lack of academically trained company tutors to deliver training to students and a lack of flexibility to modify academic curricula and teachings that would enable their adaptation to a changing context such as the productive context, are some of these obstacles that can put at risk the interest of companies for this training modality.

Figure 10 shows some of the textual contributions as an example of this assessment.

The strengths and opportunities described by the participants in this consultation, and the object of the analysis carried out, constitute weighty arguments that justify the commitment that this Autonomous Community must continue to have for Dual VET. A backing that must be accompanied by a greater investment in terms of budgets and of educational and business research and innovation.