Culturally Responsive Teaching: Its Application in Higher Education Environments

Abstract

:1. Introduction

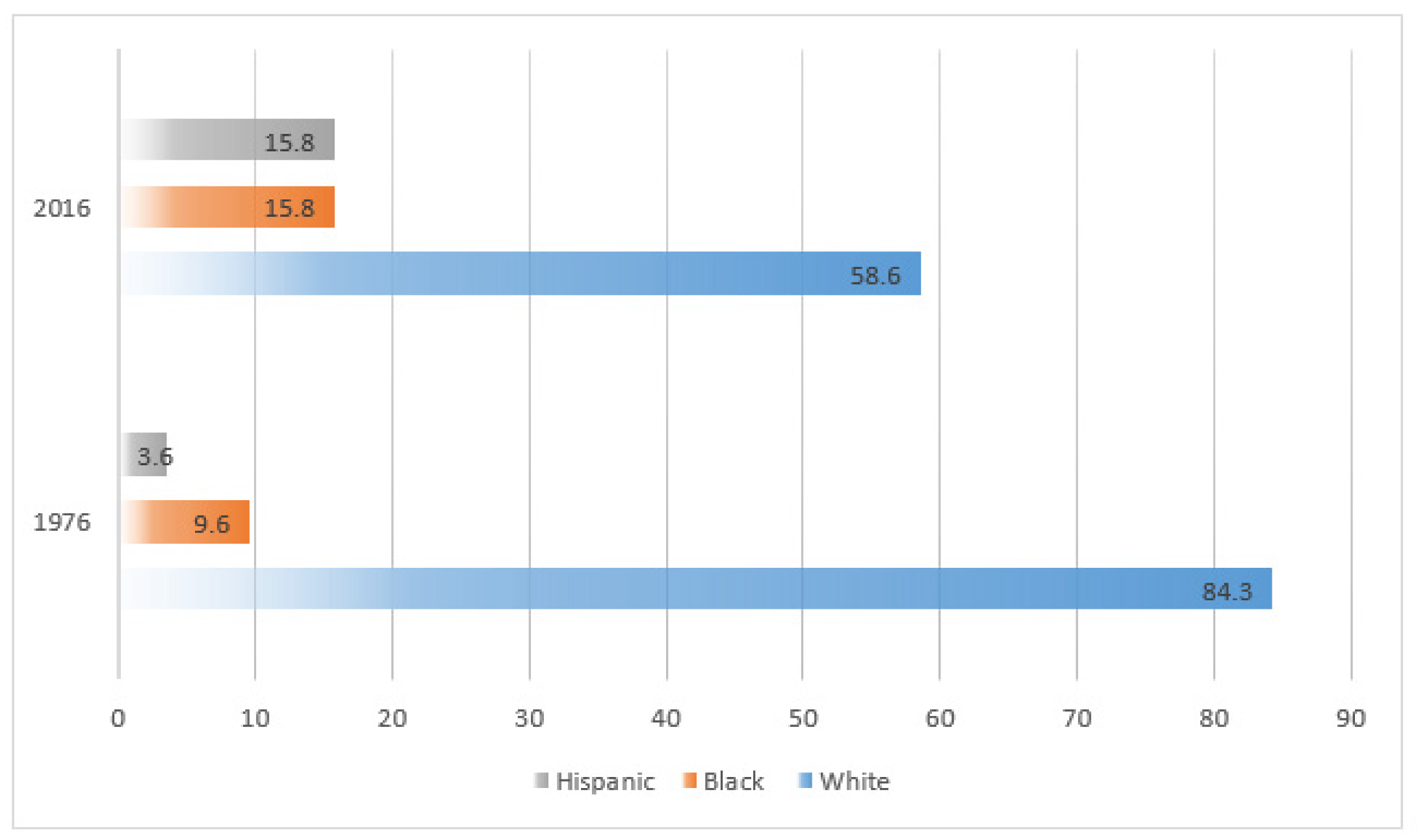

2. The Landscape of Higher Education in the United States

3. Applying Culturally Responsive Teaching in Classrooms Settings

3.1. Culturally Responsive Teaching in Higher Educational Settings

3.2. Culturally Responsive Teaching in the Online Delivery of Courses in Higher Education

3.3. Factors That Influence the Use of Culturally Responsive Teaching in Higher Educational Settings

3.4. Everyday Examples of Culturally Responsive Teaching in Higher Education

4. Higher Education Scenarios and Guiding Statements with Questions

4.1. Guiding Statements and Questions to Use with the Scenarios

- Identify the culturally sensitive issues and biased beliefs embedded in each scenario.

- How can you use the components of CRT to reconstruct each scenario?

- Identify practices that could be used in each scenario to promote the inclusion of CRT within a post-secondary context.

- What did each scenario teach you about cultural bias?

4.2. Scenario I: Seminar on Professional Leadership (Dr. Timber Is a Made-up Instructor)

4.3. Scenario II: Benza’s Dilemma

4.4. Scenario III: Experiencing a Biased Situation

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lloyd, K.M.; Tienda, M.; Zajacova, A. Trends in educational achievement of minority students since Brown v. Board of Education. In Achieving High Educational Standards for All: Conference Summary; Ready, T., Edley, C., Snow, C., Eds.; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2001; pp. 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Current Population Survey. College Enrollment and Work Activity of 2012 High School Graduates; Issue USDL-13-0670; US Department of Labor-Bureau of Labor Statistics: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- National Center for Education Statistics. Digest of Education Statistics: 2011 (NCES 2011-001). 2012. Available online: https://nces.ed.gov/pubsearch/pubsinfo.asp?pubid=2012001 (accessed on 23 April 2020).

- National Center for Education Statistics. NAEP Data Explorer. 2013. Available online: http://nces.ed.gov/nationsreportcard/naepdata/dataset.aspx (accessed on 19 February 2014).

- Texas Higher Education Coordinating Board. Interactive Access to Data. 2013. Available online: http://www.txhighereddata.org/Interactive/Accountability/ (accessed on 23 April 2020).

- Malone, B.F. Before Brown: Cultural and social capital in a rural Black school community, WEB Dubois High School, Wake Forest, North Carolina. N. C. Rev. 2008, 85, 416–447. [Google Scholar]

- National Center for Education Statistics. Projection of Education Statistics to 2024 (NCES 2016-013). 2015. Available online: https://nces.ed.gov/pubs2016/2016013.pdf (accessed on 22 April 2020).

- Jones, B.E.; Slate, J.R. Differences in academic and technical awards at Texas community colleges over time: A within groups comparison. Int. J. Univ. Teach. Fac. Dev. 2014, 4, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, R.S.; Conley, D.T. Comparing state high school assessments to standards for success in entry-level university courses. Educ. Assess. 2007, 12, 137–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Combs, J.P.; Slate, J.R.; Moore, G.W.; Bustamante, R.M.; Onwuegbuzie, A.J.; Edmondson, S.L. Gender differences in college preparedness: A statewide study. Urban Rev. 2010, 42, 441–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmer, R.T.; Davis, R.J.; Moore, J.L., III; Hilton, A.A. A nation at risk: Increasing college participation and persistence among African-American males to stimulate U.S. global competiveness. J. Afr. Am. Males Educ. 2010, 1, 105–125. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Treasury. New Report from Treasury, Educational Department: The Economic Case for Higher Education. 2012. Available online: http://www.treasury.gov/press-center/press-releases/Pages/tg1620.aspx (accessed on 23 April 2020).

- Obama, B.H. Executive Order: White House Initiative on Educational Excellence for African Americans. 2012. Available online: http://www.Whitehouse.gov/the-press-office/2012/07/26/executive-order-White-house-initiative-educational-excellence-african-am (accessed on 23 April 2020).

- Gay, G. Culturally Responsive Teaching: Theory, Research, and Practice; Teachers College Press: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Forbes, J.D. Teaching Native American values and cultures. In Teaching Ethnic Studies: Concepts and Strategies; Banks, J.A., Ed.; National Council for the Social Studies: Washington, DC, USA, 1973; pp. 200–225. [Google Scholar]

- Carjuzaa, J.; Ruff, W.G. When western epistemology and an indigenous worldview meet: Culturally responsive assessment in practice. J. Scholarsh. Teach. Learn. 2010, 10, 68–79. [Google Scholar]

- Ladson-Billings, G. But that’s just good teaching! The case for culturally relevant teaching. Theory Pract. 1995, 34, 159–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frankenberg, E. (Ed.) Lessons in Integration: Realizing the Promise of Racial Diversity in American Schools; University of Virginia Press: Charlottesville, VA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- McIntosh, P. White privilege: Unpacking the invisible knapsack. In Race, Class, and Gender: An Anthology Study; Andersen, M.L., Collins, P.H., Eds.; Wadsworth Publishers: New York, NY, USA, 1992; pp. 103–107. [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes, C.M. Culturally responsive teaching with adult language learners. In Proceedings of the Adult Education Research Conference, Manhattan, KS, USA, 20–22 May 2015; Available online: http://newprairiepress.org/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1142&context=aerc (accessed on 24 April 2020).

- Ladson-Billings, G. Toward a theory of culturally relevant pedagogy. Am. Educ. Res. J. 1995, 32, 465–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hutchison, L.F.; McAlister-Shields, L.; Jones, B. Culturally Responsive Instructional Strategies for Higher Education; Department of Curriculum and Instruction, University of Houston: Houston, TX, USA, Unpublished manuscript; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Delpit, L. Other People’s Children: Cultural Conflict in the Classroom; New Press: New York, NY, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Ellis, E.M. The impact of race and gender on graduate school socialization, satisfaction with doctoral study, and commitment to degree completion. West. Stud. Black Stud. 2001, 25, 30–45. [Google Scholar]

- Gardner, S.K. Fitting the mold of graduate school: A qualitative study of socialization in doctoral education. Innov. High. Educ. 2008, 33, 125–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banks, J. An Introduction to Multicultural Education; Allyn and Bacon: New Heights, MA, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Nieto, S. Affirming Diversity: The Socio-Political Context of Multicultural Education; Allyn & Bacon: Boston, MA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia, R.L. Teaching for Diversity: A Guide to Greater Understanding; Solution Tree Press: Bloomington, IN, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Hanley, M.S.; Noblit, G.W. Report on Cultural Responsiveness, Racial Identity and Academic Success: A Review of Literature. Retrieved from The Heinz Endowments. 2009. Available online: http://www.heinz.org/UserFiles/Library/Culture-Report_FINAL.pdf (accessed on 24 April 2020).

- Harmon, D.A. Culturally responsive teaching through a historical lens: Will history repeat itself? Interdiscip. J. Teach. Learn. 2012, 2, 12–22. [Google Scholar]

- Milner, R.H., IV. Culturally relevant teaching in a diverse urban classroom. Urban Rev. 2011, 43, 66–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladson-Billings, G. The Dreamkeepers: Successful Teachers of African American Children; Jossey-Bass Publishers: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, S.P.; West, J.E. Preparing inclusive educators: A call to action. J. Teach. Educ. 2012, 63, 291–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rueda, R.; Stillman, J. The 21st century teacher: A cultural perspective. J. Teach. Educ. 2012, 63, 245–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Psychological Association. Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Irvine, J.J. Black Students and School Failure: Policies, Practices, and Prescriptions; Greenwood Press: New York, NY, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Cochran-Smith, M.; Dudley-Marling, C. Diversity in teacher education and special education: The issues that divide. J. Teach. Educ. 2012, 63, 237–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moran, J. Culturally Relevant ESL Teaching for California Community College Teacher Educators. Master’s Thesis, University of San Francisco, San Francisco, CA, USA, 2014. Available online: https://repository.usfca.edu/capstone/68 (accessed on 24 April 2020).

- Young, E. Challenges to conceptualizing and actualizing culturally relevant pedagogy: How viable is the theory in classroom practice? J. Teach. Educ. 2010, 61, 248–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larke, P.; Wiseman, J.D.; Bradley, C. The minority mentorship project: Changing attitudes of preservice teachers for diverse classrooms. Action Teach. Educ. 1990, 12, 5–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumgartner, D.; Bay, M.; Lopez-Reyna, N.A.; Snowden, P.A.; Maiorano, M.J. Culturally responsive practice for teacher educators: Eight recommendations. Mult. Voices Ethn. Divers. Except. Learn. 2015, 15, 44–58. [Google Scholar]

- Robins, K.N.; Lindsey, R.B.; Lindsey, D.B.; Terrell, R.D. Culturally Proficient Instruction: A Guide for People Who Teach; Corwin Press: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, H.W. The White Architects of Black Education: Ideology and Power in America, 1865–1954; Teachers College Press: New York, NY, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Bustamante, R.M.; Nelson, J.A.; Onwuegbuzie, A.J. Assessing schoolwide cultural competence: Implications for school leadership preparation. Educ. Adm. Q. 2009, 45, 793–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Smith, D.R.; Ayers, D.F. Culturally responsive teaching and online learning: Implications for the globalized community college. Community College J. Res. Pract. 2014, 30, 401–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Howard, T.C. Why Race and Culture Matter in Schools: Closing the Achievement Gap in America’s Classrooms; Teachers College Press: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, I.E.; Seaman, J. Online nation: Five Years of Growth in Online Learning; Sloan Consortium: Needham, MA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, I.E.; Seaman, J.; Poulin, R.; Straut, T.T. Online Report Card: Tracking Online Education in the United States; Online Learning Consortium, Inc.: Newburyport, MA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Heitner, K.L.; Jennings, M. Culturally responsive teaching knowledge and practices of online faculty. Online Learn. 2016, 4, 54–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Woodley, X.M.; Parra, J. (Re)framing and (Re)designing instruction: Transformed teaching in traditional and online classrooms. Transform. Dialogues Teach. Learn. J. 2019, 12, 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- PeQueen, C. Cultural Competence in Higher Education Faculty: A Case Study. Ph.D. Thesis, Keiser University, Fort Lauderdale, FL, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, J. Improving teaching and learning practices for international students: Implications for curriculum, policy, and assessment. In Teaching International Students: Improving Learning for all; Ryan, J., Carroll, J., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2005; pp. 92–100. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, P.C. Counter-storying and the grand narrative of science (teacher) education: Towards culturally responsive teaching. Cult. Stud. Sci. Educ. 2011, 6, 795–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammond, Z.L. Culturally Responsive Teaching and the Brain: Promoting Authentic Engagement and Rigor among Culturally and Linguistically Diverse Students; Corwin: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Rea, D.W. Interview with Pedro Noguera: How to help students and schools in poverty. Natl. Youth-Risk J. 2015, 1, 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| Number | Characteristics |

|---|---|

| 1 | [Teachers] acknowledge the legitimacy of the cultural heritage of different ethnic groups as legacies that affect students’ dispositions. |

| 2 | [Teachers] build meaningfulness between home and school experiences as well as between academic abstractions and lived socio-cultural realities. |

| 3 | [Teachers] use a wide variety of instructional strategies that are connected to different learning styles. |

| 4 | [Teachers] teach students to know and praise their own and each other’s cultural heritage. |

| 5 | [Teachers] incorporate multicultural information, resources, and materials in subjects and skills taught in schools. |

| CRT Strategy/Resource | Definition | Classroom Practice |

|---|---|---|

| School-Wide Cultural Competence Observation Checklist (Nelson, Bustamante, and Onwuegbuzie, 2009) | This is a 33-item assessment that is designed to determine the degree of diversity found on a campus. | Students used the assessment to rate diversity and cultural aspects found on their campus. |

| Equity Audit (Skrla, Mckenzie, and Scheurich, 2008) | This is an assessment that contains 12 indicators for assessing equity and inequity in the areas of teacher quality, student programs, and student achievement. | Students used the assessment to conduct equity audits to evaluate a variety of components related to school programs, student state examination scores, and other aspects such as graduation rates. |

| Exploring Your Culture (Fralick, 2015) | This is an assessment that uses seven items for a student to evaluate their personal cultural beliefs and experiences. | The assessment allows participants to think about their own lived experiences. This can be followed by group discussion on diversity and culture. |

| Community Visit to Build Cultural Knowledge (Hutchison et al., 2018) | This is an organized and pre-set visit to a community that is led by community leaders to help teachers learn more about the social context of their campus community. | Pre-service and in-service teachers can tour their campus community over two days. The tour should be led by a community leader who can provide and explain historical information, financial information, and community resources. The leader can arrange for brief meetings community dwellers and can have a meal in a home or a community restaurant. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hutchison, L.; McAlister-Shields, L. Culturally Responsive Teaching: Its Application in Higher Education Environments. Educ. Sci. 2020, 10, 124. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci10050124

Hutchison L, McAlister-Shields L. Culturally Responsive Teaching: Its Application in Higher Education Environments. Education Sciences. 2020; 10(5):124. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci10050124

Chicago/Turabian StyleHutchison, Laveria, and Leah McAlister-Shields. 2020. "Culturally Responsive Teaching: Its Application in Higher Education Environments" Education Sciences 10, no. 5: 124. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci10050124

APA StyleHutchison, L., & McAlister-Shields, L. (2020). Culturally Responsive Teaching: Its Application in Higher Education Environments. Education Sciences, 10(5), 124. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci10050124