Abstract

Introduction: Leadership as the second factor in school improvement needs potential leaders to be effective. Method: The present study aimed to know the potential capacity of leaders in Spanish secondary schools through the adaptation of the DLI questionnaire to Spanish. To accurately adapt this questionnaire, the present research group conducted content validity processes in 2017, using the Delphi Method, in which eight experts from the Spanish Network for Research into Leadership and Academic Improvement were invited to participate (RILME). As part of a pilot test, preliminary tools were administered to 547 participants from secondary schools in Granada and Jaén (Spain). Results: The present study reports on the adaptation of the DLI instrument within the Spanish context. Acceptably high values were obtained in the analysis of reliability and internal consistency, suggesting that this item can be reliably utilised for the exploration of the dynamics of internal functioning in secondary education and the evaluation of the distribution of leadership characteristics. Conclusions: The pilot study highlights how heads of studies and department heads are potential leaders, making it easier to set up and sustain educational projects in schools.

1. Introduction

Leadership is one of the most valuable indicators in the context of education and the achievement of academic improvement. Previous research on leadership has focused on the profile possessed by leaders [1], in addition to the different forms leadership takes and the contexts in which it is developed [2]. Other studies have instead placed the focus on the educational organisation itself as a place in which individuals can learn and interact with their educators [3,4].

Recently, research has emerged targeting the identification of leaders within the school environment, analysing different types of leaders [5], and highlighting the inconsistencies between their identity owed to differences in their educational formation, socioeconomic and cultural context, experiential baggage and their degree of commitment and involvement [6,7].

Recent studies have identified the positive impact of leadership in high schools, relating it with improvements in the development of professional teacher training, the working climate, and the establishment of a system of confidence based on professional participation and learning. These studies have also highlighted the leadership figure as the key individual driving change [8]. Key individuals will be those who are trusted by their management, while they are able to mobilize other colleagues to achieve a common project. Authors such as Siskin [9] have pointed to departments as suitable places to bring about change in schools. Thus, department heads would be key figures, as they are the link between the management team and the teaching staff [10]. These findings imply important actions for schools. Firstly, it is beneficial for educational schools to initiate educational projects to secure high levels of participation from within the general educational community [11]. Secondly, there exists a large managerial responsibility to initiate a set of positive practices oriented towards the improved learning of students [4]. Finally, it is important to channel leadership in a form that distributes responsibility amongst several key individuals in schools, to support the professional development of teachers and improve the quality of teaching [12,13].

Leadership is an improvement factor if we understand it as the capacity of one or several people to involve others in a common project [14]. Building a positive school environment, establishing the conditions for a common pedagogical project, as well as promoting processes of change and internal exchanges aimed at improving student and teacher learning means improving the social and professional capital of the whole school and its agents. Often, the high demands of accountability cause principals to be unable to assume pedagogical leadership functions. Therefore, they must delegate responsibilities and empower others, such as heads of studies or department heads [15].

From this perspective, it is understood that the head of studies is the key individual who acts as the link between the groups that compose an educational school and their wider context [16]. Along with this approach, the head of studies assumes pedagogical, administrative and management roles [17,18].

Domingo-Segovia and Ritacco-Real [19] consider research management to be one of the main supports for the achievement of a distributed pedagogical leadership. According to their pertinent research, strong management enables the heads of studies to be key components in the initiation and development of processes targeting improvement in secondary schools. Similarly, Paranosic and Riveros [20] highlighted the importance of management research into key leadership figures working together towards the school’s objectives. In addition to the directors and the heads of both research studies and of schools, the head of the department is a key figure [21,22]. The head of the department is responsible for ensuring the coherence of pedagogical coordination within the research or educational institution. Besides, the head of the department is typically delegated tasks such as delivering the educational projects of the school, organising the spaces and facilities assigned to their department, and collaborating in evaluations. This takes place within the operational needs of the school, which functions according to the structural models of the individual bodies and organisational units held within it. In the same way, the relationships developed between the staff (both vertical and horizontal) to achieve efficient pedagogical coordination are also important [23].

It is therefore supported that the type of leadership exercised by management is related to the organisational disposition and professional involvement of the teaching staff. The scientific literature indicates the potential of the DLI instrument to analyse the capacity of schools or educational schools to incorporate distributed leadership modalities within their organisation and to examine the management dynamics of high schools and their tendency towards collaboration [24].

Once the heroic leadership patterns have been overcome, there is a need to find potential leaders in the schools. The construction of educational projects oriented towards school improvement needs people involved in achieving it. Moreover, given the relevance and currency of studies on educational leaders, it was found essential to provide a tool to measure the educational leadership of others who might be leaders in the school.

Many instruments have been developed to evaluate the principal’s leadership capacity [25,26], although this number is smaller when referring to middle leaders [27,28]. Many of the instruments validated in the field have focused on a person’s leadership capacity. In this case, it was interesting to analyse the role of principals, but also the leadership potential of middle leaders. In turn, the importance focuses not on the leadership capacity of the people, but on their potential and action to promote processes and carry out internal changes aimed at a common Project. The instrument that has been adapted to the Spanish context has items that go beyond valuing the leadership and management capacity of leaders. In the updated Spanish context, importance is given to the school functioning as the main context in which people involved or not, with common goals, work and interact. The involvement of teaching staff in designing and supporting the school’s goals ensures that this instrument not only evaluates leadership capacity from a distributed perspective, but also discusses the capacity of the school as a whole, where people work and whose actions must be translated into the internal changes necessary for its pedagogical improvement. Similarly, it also includes the professional identity for assuming leadership and job satisfaction, both crucial and required aspects for the correct school functioning, as well as for identifying effective leaders. Therefore, this study aims to know how pedagogical coordination is carried out in high schools based on the existence of distributed leadership modalities. At the same time, it is also intended to adapt the DLI Questionnaire to the Spanish context.

2. Methods

2.1. Study Sample

The study aimed to analyze the leadership capacity of formal and middle leaders in secondary schools in the areas of Jaén and Granada. Due to the fact that there is no official number of principals, heads of studies and department heads, we carried out an estimation of population based on the number of schools. Thus, it was found that in the area of Jaén there were 87 secondary schools and in Granada there were 94. An average of 18 participants per school was estimated, in order to balance small, medium and large schools. Consequently, it was estimated that the total population was 3709. Subsequently, we calculated the minimum sample needed to achieve a sampling error of 0.05, giving a sample of 364. The final study sample consisted of 547 educational leaders, with 54.1% men and 45.9% women, with a mean age of 47.31 (SD = 9.42). The participants were distributed in 83 principals, 97 heads of study and 367 heads of department from schools in the provinces of Granada and Jaén. Ethical approval was obtained from the University of Granada Research Ethics Committee and all participants provided informed consent.

2.2. Instrument

The instrument used was the DLI Questionnaire developed by Hulpia et al. [24]. The purpose of this questionnaire was to establish the relationships existing between the perception of distributed leadership and job satisfaction in secondary schools, and between organisational commitment of teachers and teaching leaders. A previous study, which collected 2198 responses from teachers and teaching leaders belonging to 46 schools in Flanders (Belgium) [24], interpreted findings as demonstrating “three core functions of successful leaders mentioned in the instructional and transformational leadership models (…) and in the educational change literature (…): (a) setting a vision, (b) developing people, and (c) supervising teachers’ performance” (p. 1015).

In the first section of the DLI, respondents are asked to rate the individual leadership functions of the school head teacher, head of studies and teaching leaders. For each subgroup, items were scored on a 5-point Likert scale (0 = never to 4 = always). When initially developing the item, Hulpia et al. [24] stated that it was based on “strength of the vision (…), supportive leadership behavior (…), providing instructional support, and providing intellectual stimulation (…). For supervision, we developed a scale based on the literature concerning supervising and monitoring teachers” (p. 1018).

To facilitate response-giving with regards to the characteristics of the leadership team, questions are directed towards characteristics of the school leaders when considered as a team. To this end, subscales are based on “the subscales Role Ambiguity, Group Cohesion and the Degree of Goal Consensus” (p. 1018). Items are evaluated on a Likert scale with five response options (0 = totally disagree to 4 = completely agree).

2.3. Procedure

For the adaptation of DLI [24] into Spanish, experts were asked to review the instrument according to the Delphi Method [25,26,27,28,29,30,31]. The panel of experts selected was formed by university teachers and researchers with a recognised prestige for their expertise in the field of study, and who belonged to the RILME network. The number of individuals on expert panels of previous studies varies between two and 20 experts [32,33]. Eight experts participated in the present study, all of them being university teachers with Terminal Degrees who worked in the departments of Didactics and School Management and Pedagogy at different universities (37.5% male and 62.5% female).

Review by the expert panel followed a pre-planned systematic approach that was structured according to three phases: preliminary, exploratory and final.

In the first phase, the research team explained the objective of the study. Next, a collaboration agreement was made with the participating experts. Coordinators were charged with interpreting and making relevant adjustments and corrections to the questionnaire. The original questionnaire valuable was the leadership capacity of principals. The experts decided that it would be valuable to learn about the possibilities of the leadership of other leading figures in high schools such as head of studies (responsible for pedagogical issues in Spanish secondary schools, who belongs to the management team) and department heads. Therefore, the first 13 items of the original questionnaire were tripled (Appendix A).

The exploratory phase consisted of development and adaption of the questionnaire, and finalisation of the definitive version. To achieve this, the questionnaire was sent by email to the participating experts. This email explained the objective of the research and included a registration form for each expert to complete data collection. The final questionnaire was composed of 65 items pertaining to seven dimensions contemplated on a scale described by Hulpia et al. [24]. A 5-point Likert scale was used with 0 describing “complete disagreement” and 4 describing “complete agreement.”

In the third and final phase, outcomes from the process of adaptation of the final questionnaire were synthesised. These were then administered to 53 secondary school leaders in Andalusia. This stage aimed to find the wrong items and potential errors in the items’ comprehension and redaction. Once the final test was obtained, we contacted high schools in the areas of Jaén and Granada via telephone and through institutional mail. However, due to the low response achieved, a researcher from the study team visited all schools and invited them to participate directly in person. During this visit, the researcher explained to the management teams all of the study processes, study objectives and data collection measures. The schools were assured that feedback on the study findings relating to their centre would be provided to them, should it be requested. In addition, schools were offered the option of completing the questionnaire in paper format or online, through a Google tool called Google Forms. Once agreement to participate was received from the school, data collection began with questionnaires administered between January and April of 2018. Finally, 565 answers were obtained. A total of 18 questionnaires were excluded as they were not properly completed. The study followed directives provided by the Declaration of Helsinki in relation to research projects.

2.4. Data Analysis

Content analysis was conducted to analyse the qualitative data collected. Quantitative data were analysed via descriptive statistics, exploratory factor analysis (EFA) and internal consistency estimations using the statistical software SPSS version 24.0. Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was conducted using the statistical software AMOS version 21.

The Factorial Analysis (FA) is an exploratory data analysis technique that aims to discover and analyse the structure of a set of interrelated variables in order to construct a measurement scale of factors that somehow control the original variables. The main components method was used to extract these factors, it is a multivariate statistical procedure that allows transforming a set of initial quantitative variables correlated with each other into another set with fewer orthogonal variables and designated by main components. The main components were calculated in decreasing order of importance, namely, the first one explained the maximum variance of the data, while the second one explained the maximum variance not explained by the first one, thus, successively. The last component was the one that least contributes to the explanation of the total variance of the data. In order not to find problems of assigning the item to the factor (dimension; component), the rotation of the variables is used to produce an interpretable solution in such way that the higher weights are even higher and the lowest even lower, disappearing the intermediate values, so that the factors are easily interpretable.

In this work, the varimax rotation procedure was used, because we wanted to obtain a structure in which variables would only be associated to a single factor and less associated to the remaining ones (process developed by Kaiser 1958, that later comes to be known as KMO (Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin)).

In order to apply the factorial model, there must be a correlation between the variables; if these correlations are small, they are unlikely to share common factors. The KMO (Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin) and the Barthel test are statistical procedures that allow to measure the quality of correlations between variables in order to continue with factor analysis. KMO is a statistic that varies between zero and one and compares the zero-order correlations with the correlations observed between the variables. The KMO near one indicates small partial correlation coefficients, while values close to zero indicate that factor analysis may not be a good idea, because there is a weak correlation between the variables. Barthel’s sphericity test allows us to ascertain whether the correlations are high enough for FA to be useful in estimating common factors. It is also common to evaluate the reliability and validity of measurement instruments in FA. The reliability of the instrument refers to the ownership of consistency and reproductively of the measure [34] (p. 174). An instrument is said to be reliable if it consistently and reproducibly measures a particular characteristic or interesting factor. Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was used as a measure of reliability. This extraction was at the original meeting, hence it proceeded to confirmation.

For the evaluation of the psychometric properties of the latent variables of 1st order of the perception of the culture of reliability; for the analysis of the measurement model and the structural model, the Amos v.21 software was used using the maximum likelihood method applied to the original items. The results obtained were considered in the analysis of the adjustment: for the comparative fit index (CFI), which should be greater than 0.9; for the Parsimony Goodness-of-Fit Index, which should be higher than 0.6; and for the root-mean-square error of approximation (RMSEA), which should be less than 0.10, in order to consider the quality of the good adjustment. Also, in the confirmatory factor analysis it is pertinent to evaluate the reliability and validity of the measurement instruments. The reliability of the instrument refers to the consistency and reproductively of the measure [34] (p. 174). An instrument is said to be reliable if it consistently and reproducibly measures a particular characteristic or interesting factor. Cronbach’s alpha coefficient and composite reliability are used as reliability measures; the latter gathers greater consensus among the different authors, estimates the internal consistency of the reflective items of the factor or construct, indicating that these are consistently manifestations of the latent factor. Composite reliability values above 0.7 are considered to indicate a reliability of the appropriate construct. For Cronbach’s alpha values between 0.7 and 0.8, the internal consistency is reasonable, values between 0.8 and 0.9 consistency are good and values above 0.9 consistency are very good [35]. Validity is the property of the instrument or scale of measure that evaluates whether it measures and it is the operationalization of the latent construct that is really intended to evaluate. Validity is composed of three components: factorial, convergent and discriminant. Factorial validity is generally evaluated by standardized factor weights, it is usual to assume that if these are at least 0.5, the factor has factorial reliability. The square of the standardized factor weights designates the individual reliability of the item, this is appropriate if the value obtained is at least 0.25. Convergent validity occurs when items are a reflection of a factor, that is, they strongly saturate in this factor, that is, the behavior of the items is essentially explained by this factor. This validity is evaluated using the average variance extracted (AVE); if this value is at least 0.5, then there is adequate convergent validity.

3. Results

3.1. Exploratory Factor Analysis

Firstly, the initial dimensions of support and supervision by leadership were transformed in the adaptation carried out. When the first 13 items were tripled to assess the leadership capacity not only of the management, but also of the head of studies and the head of department, two factors emerged from the factor analysis in the second one: leadership of the head of the department and management of the head of the department. The cohesive leadership team shared decision-making, and commitment dimensions were transformed by school functioning and leadership identity, according to the suggestions of the experts and what was found in the literature. The job satisfaction dimension was maintained with respect to the original instrument.

For the development and translation of the questionnaire, the original DLI was divided according to its six dimensions: support, supervision, cohesive leadership team, shared decision-making, the commitment of the organization and job satisfaction [24]. Then we applied the exploratory factor analysis with varimax rotation. Like we stated before, this was used due to the fact that we wanted to obtain a structure in each variable that would only be associated to a single factor and less associated to the remaining ones. According to the groupings of the questionnaire, we identified the following dimensions: management leadership, the leadership of the head of studies, leadership and management of the head of the department, school functioning, job satisfaction and leadership identity. Exploratory factor analysis outcomes were interpreted using KMO (with value 0.897) indicators and the Bartlett test (p = 0.000). The exploratory results presented in Table 1 corroborate the theoretical constructs proposed by the research team of the present study and the expert panel.

Table 1.

Factor loadings of DLI items adapted to Spanish.

As can be seen in Table 2, all questionnaire dimensions demonstrated high reliability, with the lowest Cronbach’s alpha produced being 0.84.

Table 2.

Reliability coefficients of the dimensions of DLI.

3.2. Confirmatory Factor Analysis

Confirmatory factor analysis followed exploratory factor analysis to solidify the dimensions. Models are deemed to have a very good fit if values for CFI (Comparative Fit Index), GFI (Goodness of Fit Index) and AGFI (Adjusted Goodness of Fit Index) are greater than 0.90 [36], or if RMSEA (Root Mean Square Error of Approximation) produces a coefficient that is lower than 0.05. If these same values are greater than 0.05 and lower than 0.10, respectively, good model fit is suggested ([34] (p. 51). Estimation of relationship effects is based on the covariance matrix developed between the considered variables. In the present study, the maximum likelihood estimation method was used to freely interpret the data. This is the method most recommended when assumptions of normal distribution may be violated within the examined population [35,37].

Table 3 presents the findings from the analysis of quality of model fit, reliability and validity of the seven dimensions. The dimension describing management demonstrated good quality of fit to the measured data χ^2/df = 3562 < 5; CFI = 0.967 > 0.90; TLI = 0.956 > 0.90; RMSEA = 0.070 < 0.08. The composite reliability value was sufficiently high (0.937), and the average variance extracted (AVE) indicator of convergence factors was adequate (0.538). Standardised factor weights (γ_ij) greater than 0.50 and squared standardised factor weights (γ_ij^2) greater than 0.25 suggest factorial reliability and reliability of individual items, respectively.

Table 3.

The goodness of fit of the measurement’s models.

The dimension describing head of studies demonstrated good fit to the observed data χ^2/df = 3.949 < 5; CFI = 0.968 > 0.90; TLI = 0.957 > 0.90; RMSEA = 0.075 < 0.08. The component reliability value was sufficiently high (0.933), and the average variance extracted (AVE) indicator of factor convergence was adequate (0.541). Standardized factor weights (γ_ij) greater than 0.50 and squared standardized factor weights (γ_ij^2) greater than 0.25 suggest factorial reliability and reliability of individual items, respectively.

The dimension describing head of department demonstrated good fit to the observed data χ^2/df = 3.742 < 5; CFI = 0.921 > 0.90; TLI = 0.912 > 0.90; RMSEA = 0.072 < 0.08. Values for component reliability were sufficiently high (0.930 for the leadership of the head of department component and 0.903 for the management of the head of department component), and the average variance extracted (AVE) indicators for factor convergence were adequate (0.571 for the leadership of the head of department component and 0.757 for the management of the head of department component (Table 3). Standardized factor weights (γ_ij) greater than 0.50 and squared standardized factor weights (γ_ij^2) greater than 0.25 suggest factorial reliability and reliability of the individual items, respectively.

The dimension describing school functioning demonstrated good fit to the observed data χ^2/df = 4.279 < 5; CFI = 0.963 > 0.90; TLI = 0.951 > 0.90; RMSEA = 0.079 < 0.08. Component reliability values were sufficiently high (0.958 for the school functioning component, 0.844 for the job satisfaction component and 0.843 for the leadership identity component), and average variance extraction (AVE) indicators of factor convergence were adequate (0.565 for the school functioning component, 0.4854 for the job satisfaction component and 0.7289 for the leadership identity component). Standardised factor weights (γ_ij) greater than 0.50 and squared standardised factor weights (γ_ij^2) greater than 0.25 suggest factorial reliability and reliability of individual items, respectively.

3.3. Distribution and Descriptive Statistics of Items in the Adaptation of the DLI Questionnaire

The following Table 4 includes a brief description of the seven dimensions.

Table 4.

Distribution and descriptive statistics of items according to dimensions.

With regards to the management leadership dimension, reported values were between 1 and 4, with an M = 3.462 and an SD = 0.630, suggesting moderate dispersion of reported responses. Reported values for the leadership of the head of studies were between 0.83 and 4, with an M = 3.417 and an SD = 0.636. The median indicating that a large majority of the responses reported were shared between “mostly agree” and “completely agree.”

Values for the leadership of the head of the department dimension generally were slightly lower than the two aforementioned dimensions, reporting values between 1 and 4, with a mean of 3.180 and a slightly larger standard deviation of 0.671. These results suggest greater variability of reported responses and a lower influence of this indicator relative to the other measured dimensions. The median score was 3.222, which is, however, similar to the medians reported for the other dimensions. Minimum and maximum values for the management of the head of the department dimension were 1 and 4, respectively. The mean value was 2.756, which is moderately lower than those found for the other measured dimensions, while the standard deviation of 0.958 is higher, suggesting a large dispersion of individual responses. The median value reported was 3.

Concerning the school functioning dimension, minimum and maximum values were 0.72 and 4, respectively, with a mean value of 3.359 and a standard deviation of 0.627, suggesting marked variability between questionnaire responses. For the median, it can be seen that this value was slightly larger than the mean, rising to 3.5, suggesting that more than 50% of individual responses reported the value describing “complete agreement.” The job satisfaction dimension scores obtained ranged between 0.83 and 4. Further, this dimension obtained the highest mean value of 3.412 and a median of 3.667. Dispersion of reported responses is marked, with a standard deviation of 0.628.

Finally, values reported for the leadership identity dimension fell between 0 and 4. With regards to the mean and the median, the values produced from the observed data were 2.748 and 3, respectively, which are considerably lower than the values reported for all other dimensions, apart from the management of the head of studies dimension. Further, the high value obtained for standard deviation, 0.891, reveals a very high dispersion of responses to the item about these dimensions. In summary, it is evident that the most influential dimensions as suggested by the calculated means and medians are management leadership, the leadership of the head of studies, school functioning and job satisfaction, with all values reported being 3.417 and above and 3.324 and above, for the median and mean, respectively.

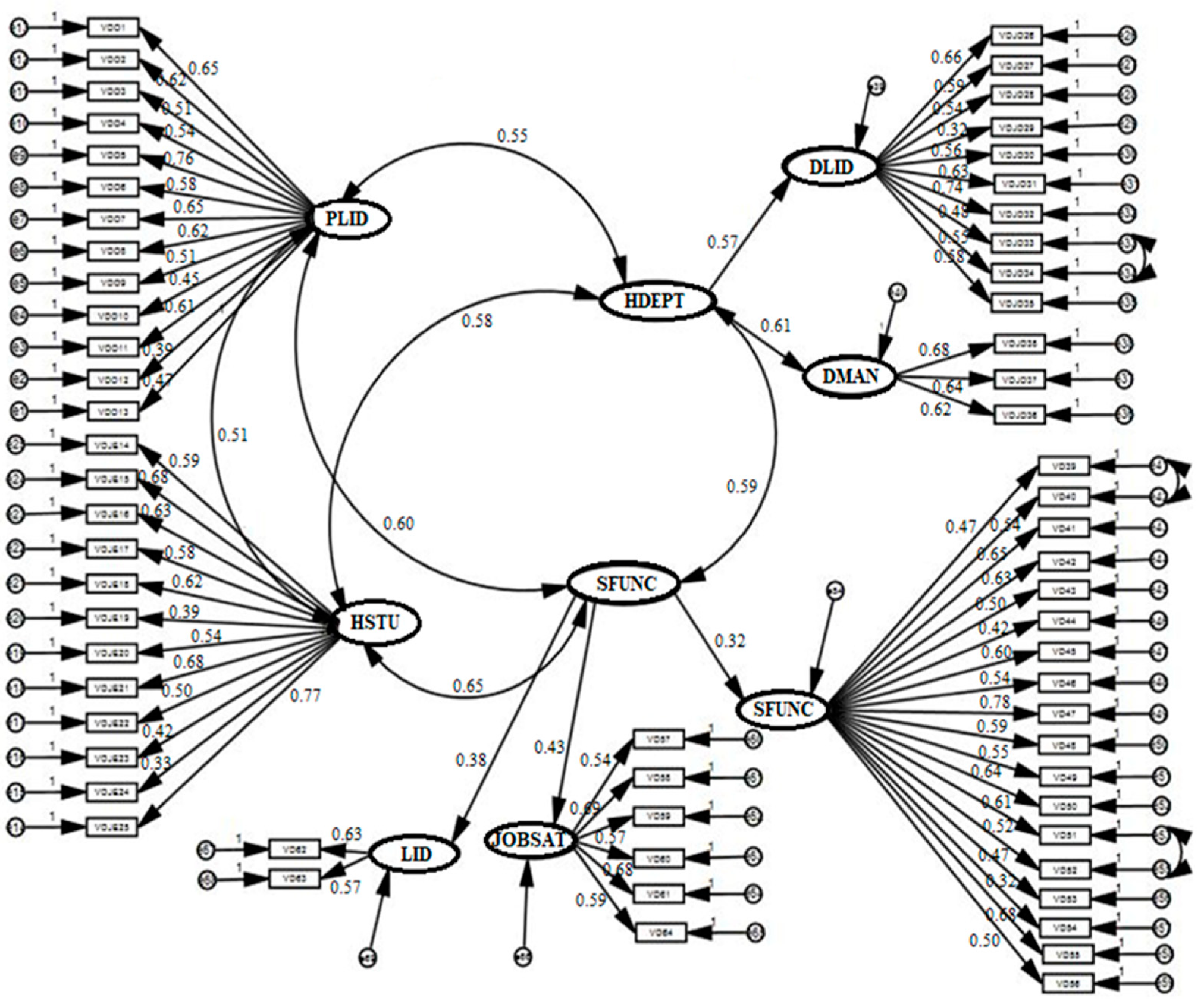

According to the original authors’ instructions of the DLI Questionnaire [24], the aim is also to analyze in detail the validity of the construction of the Spanish version of this psychometric instrument; besides, a Confirmatory Factorial Analysis was applied. Figure 1 presents the analysis confirmatory factorial performed through the structural equation model. As can be seen, the DLI Questionnaire presents a heptafactorial structure in the Spanish sample object of study, providing from this empirical cross-cultural evidence of its construct validity.

Figure 1.

Confirmatory factor analysis of the DLI Questionnaire. Note: PLID: Principal leadership; HDEPT: Head Department; DLID: Department leadership; DMAN: Department management; HSTU: Head of studies leadership; SFUNC: School Functioning; JOBSAT: Job satisfaction; LID: Leadership identity.

Analyzing the confirmatory factorial analysis in greater detail applied, the seven factors were related significantly to each other. All the items obtained high standardized regression coefficients. Table 5 presents the goodness-of-fit indices of the proposed model for the DLI Questionnaire. As can be seen, all of them show sufficient validity and good fit of the seven-dimensional model proposed.

Table 5.

Global diagnosis of the goodness-of-fit of the confirmatory factorial analysis model of the DLI Questionnaire.

4. Discussion

Principals, as organization leaders, have been investing all their time in organizational, staff-related and financial matters. The prioritisation of these tasks over purely pedagogical issues added to heritage school cultures and impeded any significant pedagogical change. In this regard, the centralized tendency which concentrated all power in the principal has contributed little to guiding schools toward improvement. Even in those cases where there was a willingness to change schools, the policy guidelines established by the administration caused frustration in the principal, who was motivated to reproduce the traditional patterns of school administration and management [38]. Therefore, it is necessary to find instruments to identify the potential of leaders outside of the principal who can achieve school improvement. Within the literature, multiple instruments have been identified dedicated to evaluating the leadership capacity of principals [25,26]. Among them, some have been interested in analyzing middle leaders, focusing on how schools work [27,28]. Among the instruments found, the DLI [24] was chosen because of the in-depth analysis it provides, not only to evaluate leadership positions, but also to evaluate the school’s functioning and assess aspects closely related to pedagogical coordination and school improvement, such as work satisfaction and leadership identity.

The strength of the adaptation of the DLI to the Spanish context consists in the evaluation of several school leaders through the same instrument. This allows comparison between different leaders and also determines their effectiveness. Unlike other questionnaires [38,39], the DLI provides the possibility of knowing the internal functioning by detecting organizational, participation and collaboration difficulties between teachers and the management team. The results found have reinforced the leadership capacity of other middle positions, particularly the head of studies and department heads, to achieve sustainability in secondary schools. Most of the teaching staff believe that, beyond ensuring their well-being, the head of studies provides them more support to improve their professional performance. This may be due to what Maureira-Cabrera [2] pointed out, who affirms that distributed leadership can be understood as “a process of social influence based on interaction, which as attribution only of the formal power of the principal or single-person leadership” (p. 10). Likewise, distributed leadership arises as a result of generating positions that enable responsibilities to be distributed and responsibilities to be assumed on their own when a need is identified. The design of practices oriented towards a common goal, empowering other educational agents to assume pedagogical responsibilities at school, emphasizing the professionalism of teaching staff and the prevalence of self-confidence, self-respect and mutual enrichment are indicators of sustainable leadership in secondary education [40].

The instrument used provides an assessment of all these necessary aspects to be able to initiate collaborative processes among the staff, in order to achieve the shared goals pursued by the school. In fact, its suitability is demonstrated by the adaptations of this instrument to other contexts. For example, López-Alfaro and Gallegos-Araya [41], in their adaptation, focused on primary education and not on secondary education, like in our case. Unlike the seven factors that emerged in our adaptation, they obtained five: Leadership Team, Support from the Director, Support from the Management Team, Supervision from the Director and Participatory Decision-Making with levels of internal consistency similar to ours and to the original scale of Hulpia et al. [24].

As Lee and Louis [14] have pointed out in a recent study on school culture and sustainable school improvement, one of the keys for success resides in achieving a strong school culture, based on multiple factors. Among them, school leadership and the establishment of a collaborative environment as a nexus between school culture and student-oriented school improvement stand out. Taking on the important role of accountability in school administration [42,43], it is time to examine which educational agents can play a role as pedagogical leaders in the school [18]. The results of this study place the head of studies as the maximum responsible for pedagogical matters in the schools, agreeing with other studies [17,19]. The proper functioning of high school depends on this individual.

Accordingly, a broad field of studies [44] has pointed out that the organizational context and its conditions affect both leadership development and the shapes it takes. This question establishes a link between the context and leadership, whose harmony (the leader’s adaptive capacity) is capable of promoting better organizational performance. Within this framework, alternative modalities of school management and administration have been studied, which concern the modification or strengthening of certain organizational structures that would provide opportunities for new leadership roles [31]. Therefore, under this perspective, it would be possible to affirm that well-placed leadership under determined contextual and organizational conditions is capable of leading the school towards improvement processes [44,45,46]. On the other hand, the head of the department is positioned as a key element in pedagogical matters; identifying with “a figure that seeks the welfare of teachers, encourages and supports them to improve their professional practices” as suggested the findings of De Angelis [47]. These results coincide with the emerging and promising area of research on middle leaders [48,49,50,51], somewhat separate from that related to distributed leadership [52].

5. Conclusions

The present study sought to adapt and validate the DLI scale in a Spanish context, with the final aim of analysing the leadership capacity of key figures in secondary schools. This instrument also made it possible to identify the outstanding features that support high-school functioning, moving the focus towards pedagogical coordination and collaboration within learning processes, leadership identity and job satisfaction.

In the process of validating the questionnaire, the technique of modelling covariant structures was employed to evaluate the multidimensionality of the scale. Given the requirements of using this technique, preservation of the psychometric properties of the constructs evaluated in the present study was assured.

The findings obtained from the adaptation of the DLI to the Spanish context make it one of the most suitable instruments for assessing the leadership capacity of different leaders in schools. In turn, it includes questions related to school functioning. It provides keys to establish an overview of how the educational agents interact, participate, and are committed and involved in order to improve the school’s pedagogical coordination and, consequently, the students’ learning.

The sample of 547 principals and middle leaders is sufficiently representative to be able to generalise this study’s results. In order to begin the search for school solutions, it is necessary to have a comprehensive and in-depth understanding of the status of schools. This instrument, because of the breadth of issues it contains, has proven to be a valid tool for this purpose.

The values obtained for each dimension reveal a large level of consistency and correlation between the considered dimensions, making it possible to confirm that the questionnaire is useful for analysing leadership capacity of leaders in a Spanish context. The posing of homonymous questions to various educational figures enabled the relationships between the leadership capacity of these individuals and the general functioning of the school to be elucidated.

In summary, the present study has confirmed that management leadership is strongly correlated with the leadership of the head of studies and school functioning. Uncovering this relationship gives weight to current international trends towards promoting pedagogical leadership as an important factor in academic improvement. Sharing and delegating leadership throughout the school encourages the exchange of practices and collaboration, in addition to influencing the motivational climate of the school and the instructional processes that take place within it.

Similarly, a strong association was identified between the leadership capacity of the head of studies and school functioning. In the Spanish context, excessive bureaucratic practices that surround management practices mean that strictly pedagogical questions are often delegated to the head of studies. Empowerment of the heads of studies as instructional leaders assures that pedagogical processes are more coordinated and cohesive, being incorporated into common projects to the greater benefit of the students.

However, the figure of the head of the department as a potential leader appears to be less defined than their corresponding figures in other contexts. This is evidenced by the low strength of correlations identified between the dimensions of the leadership of the head of the department and management of the department with the other dimensions. Future studies should seek to expand the types of samples examined, in addition to examining further the Spanish context outside of the two provinces included in the present study. Finally, richer information will be garnered by utilising complementary techniques of a more qualitative nature.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.G.-M. and P.J.A.T.; formal analysis, J.L.U.-J.; methodology, C.B.; writing—original draft, I.G.-M., P.J.A.T. and J.L.U.-J.; writing—review and editing, C.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was funded by the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation. Grant number FPU14/05050.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

DLI Questionnaire (English Version).

Table A1.

DLI Questionnaire (English Version).

| First part | |||||

| To what extent the coordination...? | Value | ||||

| 1. Establishes a vision of the centre that is listed in the Management Project | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 2. Reflect, through dialogue with staff, on the institute’s vision | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 3. Encourages opportunities for teachers to improve their professional ability | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 4. Provides teacher support in their professional performance | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 5. Explains their reasons for sometimes questioning the teaching work or certain actions of teachers | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 6. Is available after school to help teachers when they need help | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 7. Seek the personal well-being of teachers | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 8. Encourages me to grow professionally | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 9. Encourages me to innovate my teaching practices | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 10. Ensure that teachers have time and space to interact professionally | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 11. Assess staff performance | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 12. Participates in the evaluation of the teacher teaching and learning process | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 13. Participates in the training assessment of teachers | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| To what extent does the head of studies...? | |||||

| 14. Establish a vision of the centre that is listed in the Management Project | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 15. Reflect, through dialogue with staff, on the institute’s vision | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 16. Provides teacher support in their professional performance | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 17. Sometimes explains their reasons when questioning teachers | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 18. Is available after school to help teachers when they need help | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 19. Seek the personal well-being of teachers | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 20. Encourages me to grow professionally | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 21. Encourages me to innovate my teaching practices | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 22. Ensure that teachers have time and space to interact professionally | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 23. Assess staff performance | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 24. Participates in the evaluation of the teacher teaching and learning process | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 25. Participates in the training assessment of teachers | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| To what extent does the head of department? | |||||

| 26. Establishes a long-term view of the department | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 27. Reflect on the department’s vision | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 28. Encourage teachers | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 29. Provides teacher support in their professional performance | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 30. Explains your reasons for questioning, at times, the faculty in your department | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 31. Is available after school to help teachers when they need help | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 32. Seek the personal well-being of teachers | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 33. Encourages me to grow professionally | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 34. Encourages me to innovate my teaching practices | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 35. Ensure that teachers have time and space to interact professionally | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 36. Assess staff performance | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 37. Participates in the evaluation of the teacher teaching and learning process | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 38. Participates in the training assessment of teachers | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Second part | |||||

| Item | Value | ||||

| 39. In our institute there is an effective management team | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 40. The management team manages the centre efficiently | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 41. The management team supports the goals I would like to achieve at our centre | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 42. All members of the management team are involved with the same intensity in achieving the central objectives of the institute | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 43. In our institute, each teacher has the role that belongs to him or her, taking into account his or her competences | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 44. Members of the management team distribute their time equally | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 45. Members of the management team are clear about school objectives | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 46. The management team assumes the responsibilities linked to its office | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 47. The management team shows a willingness to innovation | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 48. The functions of the management team are delimited | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 49. Coordination and supervision of tasks and responsibilities among staff is a form of leadership that enables the school’s goals to be achieved | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 50. Leadership is shared among staff | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 51. As a teacher I believe that I am allowed to participate in the decision-making process | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 52. As a teacher, I believe that I participate in the decision-making process | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 53. There is a coordination committee structure that makes decision-making effective | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 54. Functional communication is facilitated between staff | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 55. There is an optimal level of autonomy in decision-making | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 56 My institute motivates me to develop my teaching skills | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 57. I am proud to be part of the team at this centre | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 58. I’m really concerned about the fate of our center | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 59. I find that my values and the values of this institute are similar | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 60. I usually talk to my friends about how delighted I am to work at this institute | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 61. I am glad to have chosen this institute to work | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 62. To what extent I consider my work to be a leading teacher | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 63. I like to play my leadership role. | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 64. I want to continue to play my professional role in this institute | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 65. If I could choose again, I would trade my work for another profession | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

Table A2.

DLI Questionnaire (Spanish Version).

Table A2.

DLI Questionnaire (Spanish Version).

| First part | |||||

| Ítem ¿En qué medida la dirección…? | Valoración | ||||

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| ¿En qué medida la jefatura de estudios…? | |||||

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| ¿En qué medida el jefe/a de departamento? | |||||

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Second part | |||||

| Ítem | Valoración | ||||

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

References

- Verger, A.; Normand, R. Nueva gestión pública y educación: Elementos teóricos y conceptuales para el estudio de un modelo de reforma educativa global. Educ. Soc. 2015, 132, 599–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maureira-Cabrera, O. Prácticas del liderazgo educativo: Una mirada evolutiva e ilustrativa a partir de sus principales marcos, dimensiones e indicadores más representativos. Rev. Educ. 2018, 42, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Hulsbos, F.; Evers, A.; Kessels, J.W. Learn to lead: Mapping workplace learning of school leaders. Vocat. Learn. 2016, 9, 21–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louis, K. Changing the culture of schools: Professional community, organizational learning, and trust. J. Sch. Leadersh. 2007, 16, 477–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Martínez, I.; Tadeu, P. The influence of pedagogical leadership on the construction of professional identity: A systematic review. J. Soc. Stud. Educ. Res. 2018, 9, 145–162. [Google Scholar]

- Arvaja, M. Building teacher through the process of identity positioning. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2016, 59, 392–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, I.; Batista, P.; Graça, A. Professional Identity in Analysis: A Systematic Review of the Literature. Open Sport Sci. J. 2014, 7, 83–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piyaman, P.; Hallinger, P.; Viseshsiri, P. Addressing the achievement gap: Exploring principal leadership and teacher professional learning in urban and rural primary schools in Thailand. J. Educ. Adm. 2017, 55, 717–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siskin, L. Department as Different Worlds: Subject subcultures in Secondary Schools. Educ. Adm. Q. 1991, 7, 134–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klar, H.W. Fostering department chair instructional leadership capacity: Laying the groundwork for Distributed instructional leadership. Int. J. Leadersh. Educ. Theor. Pract. 2012, 15, 175–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahim, B. Decentralized decision making and educational outcomes in public schools Evidence from Pakistan. Int. J. Educ. Manag. 2019, 33, 1625–1640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigby, J. Principals’ sensemaking and enactment of teacher evaluation. J. Educ. Adm. 2015, 53, 374–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, E. Being a teacher and a teacher educator-developing a new identity? Prof. Dev. Educ. 2014, 40, 436–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.; Louis, K. Mapping a strong school culture and linking it to sustainable school improvement. Teach. Teach. Educ. 2019, 81, 84–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Martínez, I. Coordinación Pedagógica y Liderazgo Distribuido En Los Institutos de Secundaria. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Granada, Granada, Spain, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Ministerio de Educación Cultura y Deporte. Estudio Talis 2013. Estudio Internacional de la Enseñanza y el Aprendizaje; Ministerio de Educación Cultura y Deporte: Madrid, Spain, 2013; Available online: www.mecd.gob.es/dctm/inee/internacional/talis2013/talis2013informeespanolweb.pdf?documentId=0901e72b819e1729 (accessed on 20 December 2019).

- Barrios-Arós, C.; Camarero-Figuerola, M.; Tierno-García, J.M.; Iranzo-García, P. School management models and functions in Spain—The case of Catalonia. Rev. Iberoam. Educ. 2013, 67, 89–106. [Google Scholar]

- Waite, D.; Nelson, S. Una revisión del liderazgo educativo. Rev. Esp. Pedag. 2005, 232, 389–406. [Google Scholar]

- Domingo-Segovia, J.; Ritacco-Real, M. Contribution of the Guidance Department to the pedagogical leadership development: A study on the opinion of the high school directors in Andalusia. Educ. Rev. 2015, 31, 199–218. [Google Scholar]

- Paranosic Paranosic, N.; Riveros, A. The metaphorical department head: Using metaphors as analytic tools to investigate the role of department head. Int. J. Leadersh. Educ. 2017, 20, 432–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantón-Mayo, I.; Cañón-Rodríguez, R.; Arias-Gago, A.R.; Baelo-Álvarez, R. Expectativas de los futuros profesores de Educación Secundaria. Enseñ. Teach. 2015, 33, 105–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Su, X.; Bozeman, B. Family friendly policies in STEM departments: Awareness and determinants. Res. High. Educ. 2016, 57, 990–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hulpia, H.; Devos, G.; Rosseel, Y. Development and Validation of Scores on the Distributed Leadership Inventory. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 2009, 69, 1013–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hulpia, H. Distributed Leadership and Organizational Outcomes in Secondary Schools. Ph.D. Thesis, Ghent University, Ghent, Belgium, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Condon, C.; Clifford, M. Measuring Principal Performance: How Rigorous are Commonly Used Principal Performance Assessment Instruments? A Quality School Leadership Issue Brief; American Institutes for Research: Washington, DC, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Pounder, D. School leadership preparation and practice survey instruments and their uses. J. Res. Leadersh. Educ. 2012, 7, 254–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fromm, G.; Hallinger, P.; Volante, P.; Wang, W.C. Validating a Spanish version of the PIMRS: Application in national and cross-national research on instructional leadership. Educ. Manag. Adm. Leadersh. 2017, 45, 419–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beycioglu, K.; Ozer, N.; Ugurlu, C.T. Distributed leadership and organizational trust: The case of elementary schools. Proced. Soc. Behav. Sci. 2012, 46, 3316–3319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Cabero, J.; Barroso, J. The Use of Expert Judgment for Assessing ICT: The Coefficient of Expert Competence. Bordón 2013, 65, 25–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pozo, M.T.; Gutiérrez, J.; Rodríguez, C. El uso del método Delphi en la definición de los criterios para una formación de calidad en animación sociocultural y tiempo libre. J. Educ. Res. 2007, 25, 351–366. [Google Scholar]

- Reguant-Álvarez, M.; Torrado-Fonseca, M. El método Delphi. REIRE 2016, 9, 87–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant, J.S.; Davis, L.L. Selection and use of content experts for instrument development. Res. Nurs. Health 1997, 20, 269–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGartland, D.; Berg-Weger, M.; Tebb, S.S.; Lee, E.S.; Rauch, S. Objectifying content validity: Conducting a content validity in social work research. Soc. Work Res. 2003, 27, 94–104. [Google Scholar]

- Marôco, J. Análise de Equações Estruturais: Fundamentos Teóricos, Software & Aplicações; ReportNumber, Lda: Pêro Pinheiro, Portugal, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Pestana, M.H.; Gageiro, J.N. Análise de Dados Para Ciências Sociais: A Complementaridade Do SPSS, 4th ed.; Edições Sílabo: Lisboa, Spain, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Kline, P. An Easy Guide to Factor Analysis; Routledge: London, UK, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, L.T.; Bentler, P.M.; Kano, Y. Can test statistics in covariance structure analysis be trusted? Psych. Bull. 1992, 112, 351–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullman, J.B. Using Multivariate Statistics; Harper & Row. Cícero: New York, NY, USA, 1996; pp. 709–811. [Google Scholar]

- Green, M.T.; Rodriguez, R.A.; Wheeler, C.A.; Baggerly-Hinojosa, B. Servant leadership: A quantitative review of instruments and related findings. Serv. Leadersh. Theor. Pract. 2016, 2, 5. [Google Scholar]

- Fullan, M. All Systems Go: The Change Imperative for Whole System Reform; Sage: Thousands Oaks, CA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- López-Alfaro, P.; Gallegos-Araya, V. Estructura factorial y consistencia interna del inventario de liderazgo distribuido (DLI) en docentes chilenos. Actual. Invest. Educ. 2015, 15, 255–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz-Delgado, M.A.; García-Martínez, I. Standards for school principals in Mexico and Spain: A comparative study. Educ. Policy Anal. Arch. 2019, 27, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leithwood, K.; Riehl, C. Qué sabemos sobre el liderazgo educativo. In Cómo Liderar Nuestras Escuelas: Aportes Desde la Investigación; Área de Educación Fundación Chile: Santiago, Chile, 2009; pp. 17–34. [Google Scholar]

- Spillane, J. The practice of leading and managing teaching in educational organisations. In Leadership for 21st Century Learning; Fundació Jaume Bofill: Barcelona, Spain, 2013; pp. 59–82. [Google Scholar]

- Hallinger, P. A conceptual framework for systematic reviews of research in educational leadership and management. J. Educ. Adm. 2013, 51, 126–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallinger, P.; Heck, R.H. Collaborative leadership and school improvement: Understanding the impact on school capacity and student learning. Sch. Leadersh. Manag. 2010, 30, 95–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gronn, P. From distribute to hybrid leadership practice. In Distributed Leadership: Different Perspectives; Harris, A., Ed.; Springer: London, UK, 2009; pp. 197–218. [Google Scholar]

- De Angelis, K.J. The characteristics of High School Department Chairs: A national perspective. High Sch. J. 2013, 97, 107–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grootenboer, P. The Practices of School Middle Leadership: Leading Professional Learning; Springer: Singapore, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Gurr, D.; Drysdale, L.; Mulford, B. Instructional Leadership in Three Australian Schools. Int. Stud. Educ. Adm. 2007, 35, 20–29. [Google Scholar]

- Gurr, D. School middle leaders in Australia, Chile and Singapore. Sch. Leadersh. Manag. 2018, 39, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spillane, J. Distributed Leadership; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).