Perceived Benefits of a Standardized Patient Simulation in Pre-Placement Dietetic Students

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Sampling

2.2. Simulation

2.3. Implementation

2.4. Data Collection and Analysis

2.4.1. Phase One

2.4.2. Phase Two

3. Results

3.1. Perceived Confidence in Monitoring and Evaluation

3.2. Perceptions on How Simulation Influenced Confidence

“I made so many mistakes, but even though it wasn’t that well done I found it rewarding to show myself that I can do it. And that got me excited, you know, when everything comes together in your brain from 3 years of study for the first time, and I thought ‘I’ve got this’. That rewarding feeling motivates me to study. I got a sense that I can actually be useful.”[Participant 7, FGD 1]

“It did increase your confidence as well because you saw the how everything fits together. Like that’s where the bed chart lives and that’s what it looks like, that increased my confidence too. Once you were on placement you remembered seeing things in simulation lab and you relate that memory to that situation which I think does calm you a little bit and increase your confidence because you’ve been there before.”[Participant 1, FGD 1]

“It made me think this is the right choice, this is where I belong. I got excited during it, but also afterwards. I realised this is huge, there’s so much to learn, but it was a taste and I realised that I can do this.”[Participant 10, FGD 1]

“It does solidify more what we actually do as a dietitian and I think it’s something we should have done more of to actually practise those skills in real life examples.”[Participant 4, FGD 2]

“It would be good to do more of it is because you’re learning how to be physically with a patient, you’re not even concentrating on what you’re saying. You’re thinking where do I stand? Am I an appropriate space away? Am I doing too much with my hands, I dropped my pen what do I do?”[Participant 3, FGD 1]

“It helped me feel comfortable. The familiarity reduced the anxiety of the unknown, so then when I went onto placement, I felt much more comfortable that I can walk onto a ward and follow the right steps rather than it being a completely new environment.”[Participant 2, FGD 2]

“You also got to see how other people did things and see what works well and what parts you can take and put into practice yourself. You get taught one way, but then in reality in the simulation you can do it how you feel comfortable to you. Then watching other people, you can learn from them and use things that might work well for you as well.”[Participant 8, FGD 1]

“Observing also contributes to that comfort. It’s like watching your supervisor on placement, observing them and then having a go, watching your peers do it makes you realise that you can do it as well. It makes it feel simpler and more doable.”[Participant 7, FGD 1]

“I found the post very helpful to start that reflective process that we need for medical nutrition therapy. It drew out my own feelings with how I went, what I can improve on and what I did well. That self-reflection was helpful, instead of just expecting feedback straight away.”[Participant 1, FGD 2]

“You realised, oh ok that’s what it’s going to be like on placement. You felt safe because you weren’t being assessed, but you still had all your classmates watching you, so it was like you are getting assessed because you’re being observed and eyes are on you for the majority of the time, which is just like placement. I think that was really valuable because you realised oh ok this is what it’s going to feel like, and it’s ok.”[Participant 1, FGD 1]

“The supportive aspect of it, it was being recorded and you wore a microphone and if you did need to wave your flag and say ‘help’ it would be ok, but I was able to get through it and it was nice to show myself that I was able to get through that situation. I found it to be really reassuring, as opposed to if it was being assessed it would have been more stressful.”[Participant 8, FGD 1]

“I think the fact that it was a simulation patient room in its natural environment, so we followed a real process. We walked in and washed our hands, introduced ourselves…. the patient was lying in a bed, they had a tray next to them they had a mountain of nutritional supplements. It all gave a sense of realism to the experience. I found that really helpful.”[Participant 2, FGD 1]

“For me it was a real-life insight into what we would actually experience on placement. It was almost realistic of the type of situation you would encounter when on placement….it was really valuable because it confirmed that I’d made the right career choice.”[Participant 3, FGD 1]

“I think just because you’re in that real-life setting, you’re learning how to be physically with a patient, taking into account all the smells and noises. For me that was a big thing in the simulation, needing to navigate the physical space and figure out how to position myself.”[Participant 7, FGD 1]

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ker, J.; Bradley, P. Simulation in medical education. In Understanding Medical Education: Evidence, Theory and Practice; Swanwick, T., Ed.; Wiley Blackwell: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2013; pp. 175–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, J.G.; Carney, H. The effect of formative capstone simulation scenarios on novice nursing students’ anxiety and self-confidence related to initial clinical practicum. Clin. Simul. Nurs. 2017, 13, 116–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, K.L.; Gutschall, M.D. The time is now: A blueprint for simulation in dietetics education. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2015, 115, 183–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhoades, P.; Ryan, C.; Erickson, D.; Strahan, B. An objective method of assessing the clinical abilities of dietetics interns. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 1998, 98, 752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pender, F.T.; de Looy, A.E. The testing of clinical skills in dietetic students prior to entering clinical placement. J. Hum. Nutr. Diet. Off. J. Br. Diet. Assoc. 2004, 17, 17–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farahat, E.; Rice, G.; Daher, N.; Heine, N.; Schneider, L.; Connell, B. Objective structured clinical examination (OSCE) improves perceived readiness for clinical placement in nutrition and dietetic students. J. Allied Health 2015, 44, 208–214. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Farahat, E.; Javaherian-Dysinger, H.; Rice, G.; Schneider, L.; Daher, N.; Heine, N. Exploring Students’ Perceptions of the educational value of formative objective structured clinical examination (OSCE) in a nutrition program. J. Allied Health 2016, 45, 20–26. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hampl, J.S.; Herbold, N.H.; Schneider, M.A.; Sheeley, A.E. Using standardized patients to train and evaluate dietetics students. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 1999, 99, 1094–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, S.; Dart, J.; Bone, C.; Palermo, C. Dietetic student preparedness and performance on clinical placements: Perspectives of clinical educators. J. Allied Health 2015, 44, 101–107. [Google Scholar]

- Henry, B.W.; Smith, T.J. Evaluation of the FOCUS (Feedback on Counseling Using Simulation) instrument for assessment of client-centered nutrition counseling behaviors. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2010, 42, 57–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todd, J.D.; McCarroll, C.S.; Nucci, A.M. High-fidelity patient simulation increases dietetic students’ self-efficacy prior to clinical supervised practice: A preliminary study. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2016, 48, 563–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, V.S.; Rothpletz-Puglia, P.; Denmark, R.; Byham-Gray, L. Comparison of standardized patients and real patients as an experiential teaching strategy in a nutrition counseling course for dietetic students. Patient Educ. Couns. 2015, 98, 168–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tada, T.; Moritoshi, P.; Sato, K.; Kawakami, T.; Kawakami, Y. Effect of simulated patient practice on the self-efficacy of Japanese undergraduate dietitians in nutrition care process skills. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2018, 50, 610–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buchholz, A.C.; Vanderleest, K.; MacMartin, C.; Prescod, A.; Wilson, A. Patient simulations improve dietetics students’ and interns’ communication and nutrition-care competence. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2020, 52, 377–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fiedler, K.M.; Beach, B.L. Microteaching: A model for employee counseling education. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 1979, 75, 674–678. [Google Scholar]

- Palominos, E.; Levett-Jones, T.; Power, T.; Martinez-Maldonado, R. Healthcare students’ perceptions and experiences of making errors in simulation: An integrative review. Nurse Educ. Today 2019, 77, 32–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoellner, J.; Harris, J.E. Mixed-methods research in nutrition and dietetics. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2017, 117, 683–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Decker, S.; Fey, M.; Sideras, S.; Caballero, S.; Rockstraw, L.; Boese, T.; Franklin, A.E.; Gloe, D.; Lioce, L.; Sando, C.R.; et al. Standards of best practice: Simulation standard VI: The debriefing process. Clin. Simul. Nurs. 2013, 9, S26–S29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudolph, J.W.; Raemer, D.B.; Simon, R. Establishing a safe container for learning in simulation: The role of the presimulation briefing. Simul. Healthc. J. Soc. Simul. Healthc. 2014, 9, 339–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motola, I.; Devine, L.A.; Chung, H.S.; Sullivan, J.E.; Issenberg, S.B. Simulation in healthcare education: A best evidence practical guide. AMEE Guide No. 82. Med Teach. 2013, 35, e1511–e1530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, M.; Sevdalis, N.; Paige, J.; Paragi-Gururaja, R.; Nestel, D.; Arora, S. Identifying best practice guidelines for debriefing in surgery: A tri-continental study. Am. J. Surg. 2012, 203, 523–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bajaj, K.; Meguerdichian, M.; Thoma, B.; Huang, S.; Eppich, W.; Cheng, A. The PEARLS healthcare debriefing tool. Acad. Med. J. Assoc. Am. Med Coll. 2018, 93, 336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Myers, E. Nutrition care process and model part I: The 2008 update. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 2008, 108, 1113–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Guide for creating self-efficacy scales. In Self-Efficacy Beliefs of Adolescents; Pajares, F., Urdan, T., Eds.; Information Age Publishing: Charlotte, NC, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- IBM. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows; IBM Corp: Armonk, NY, USA, 2016; Volume 24.0. [Google Scholar]

- Liamputtong, P. Research Methods in Health: Foundations for Evidence-Based Practice, 3rd ed.; Liamputtong, P., Ed.; Oxford University Press: South Melbourne, Australia, 2016; p. 520. [Google Scholar]

- Liamputtong, P. Qualitative Research Methods, 4th ed.; Oxford University Press: South Melbourne, Australia, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Usher, K.; Jackson, D. Qualitative methodology: A practice guide. In Phenomenology; Mills, J., Birks, M., Eds.; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2014; pp. 181–197. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, G.; McCullough, M.; Maxwell, A.P.; Gormley, G.J. Ethical reasoning through simulation: A phenomenological analysis of student experience. Adv. Simul. (Lond. Engl.) 2016, 1, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pollock, C.; Biles, J. Discovering the lived experience of students learning in immersive simulation. Clin. Simul. Nurs. 2016, 12, 313–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liamputtong, P. Research Methods in Health, 2nd ed.; Oxford University Press: South Melbourne, Australia, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Ivankova, N.V.; Creswell, J.W.; Stick, S.L. Using mixed-methods sequential explanatory design: From theory to practice. Field Methods 2006, 18, 3–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez, K.A.; Willis, D.G. Descriptive versus interpretive phenomenology: Their contributions to nursing knowledge. Qual. Health Res. 2004, 14, 726–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, J.; Osborn, M. Interpretive phenomenological analysis. In Qualitative Psychology: A Practical Guide to Research Methods; Smith, J.A., Ed.; Sage Publication Inc.: London, UK, 2007; pp. 53–80. [Google Scholar]

- Green, J.; Willis, K.; Hughes, E.; Small, R.; Welch, N.; Gibbs, L.; Daly, J. Generating best evidence from qualitative research: The role of data analysis. Aust. New Zealand J. Public Health 2007, 31, 545–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lincoln, Y.S.; Guba, E.G. Naturalistic Inquiry; Sage Publication Inc.: Beverly Hills, CA, USA, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Tufford, L.; Newman, P. Bracketing in qualitative research. Qual. Soc. Work 2010, 11, 80–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbs, D.M.; Dietrich, M. Using high fidelity simulation to impact occupational therapy student knowledge, comfort, and confidence in acute care. Open J. Occup. Ther. (Ojot) 2017, 5, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knecth-Sabres, L.J.; Kovic, M.; Wallingford, M.; St.Admand, L.E. Preparing occupation therapy students for the complexities of clinical practice. Open J. Occup. Ther. (Ojot) 2013, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swanepoel, E.; Tweedie, J.; Maher, J. Building dietetic student confidence and professional identity through participation in a university health clinic. Nutr. Diet. 2016, 73, 229–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawker, J.A.; Walker, K.Z.; Barrington, V.; Andrianopoulos, N. Measuring the success of an objective structured clinical examination for dietetic students. J. Hum. Nutr. Diet. Off. J. Br. Diet. Assoc. 2010, 23, 212–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gibson, S.J.; Davidson, Z.E. An observational study investigating the impact of simulated patients in teaching communication skills in preclinical dietetic students. J. Hum. Nutr. Diet. Off. J. Br. Diet. Assoc. 2016, 29, 529–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Shea, M.-C.; Palermo, C.; Rogers, G.D.; Williams, L.T. Simulation-Based Learning experiences in dietetics programs: A systematic review. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayes, K.; Feather, A.; Hall, A.; Sedgwick, P.; Wannan, G.; Wessier-Smith, A.; Green, T.; McCrorie, P. Anxiety in medical students: Is preparation for full-time clinical attachments more dependent upon differences in maturity or on educational programmes for undergraduate and graduate entry students? Med Educ. 2004, 38, 1154–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levett-Jones, T.; Lapkin, S. A systematic review of the effectiveness of simulation debriefing in health professional education. Nurse Educ. Today 2014, 34, e58–e63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Topping, K.J. The effectiveness of peer tutoring in further and higher education: A typology and review of the literature. High. Educ. 1996, 32, 321–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, H.; Mancuso, L. Social cognitive theory, metacognition, and simulation learning in nursing education. J. Nurs. Educ. 2012, 51, 543–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariani, B.; Cantrell, M.A.; Meakim, C. Nurse Educators’ perceptions about structured debriefing in clinical simulation. Nurs. Educ. Perspect. 2014, 35, 330–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

|

|

| Statements | Pre-simulation 1 (n = 37) | Post-simulation 1 (n = 33) | P 2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gather nutrition assessment information from a variety of sources | 6 (5–7) | 8 (7–9) | 0.000 |

| Identify relevant measures and/or data when I monitor and evaluate a patient’s progress | 5 (4.5–7) | 7 (6–8) | 0.000 |

| Compare a patients’ current findings (e.g., biochemical, anthropometric, dietary) with intervention goals | 6 (4–7) | 7 (6–8) | 0.002 |

| Evaluate whether the nutrition problem has changed | 6 (5–7) | 8 (6.5–8) | 0.000 |

| Check a patient’s compliance with an intervention plan | 6 (5.5–8) | 8 (7–9) | 0.000 |

| Analyze change in a patient’s anthropometric measurement/s | 7 (5–8) | 7 (6–8) | 0.282 |

| Analyze change in a patient’s biomedical data | 7 (5–8) | 8 (6–8) | 0.066 |

| Analyze nutrition impact symptoms (e.g., nausea, vomiting, bowel movements) | 7 (6–8) | 8 (7–9) | 0.000 |

| Explain potential causes for variance from expected outcomes | 5 (4–7) | 7 (6–8) | 0.000 |

| Determine factors that may hinder a patient’s progress | 6 (5–7) | 7 (6–8) | 0.000 |

| Start a conversation with a patient | 7 (6–8) | 8 (7–9) | 0.002 |

| Negotiate a nutrition intervention with a patient or medical team member within a clinical setting | 5 (4–6.5) | 7 (7–8) | 0.000 |

| Total score † | 74 (62–83) | 89 (81–98.5) | 0.000 |

| Percentage total score | 62 (52–69) | 74 (68–82) | 0.000 |

| Identified Theme, Times Identified | Theme Description | Example Quotes |

|---|---|---|

| Familiarization, n = 9 | Students found familiarization to the hospital setting increased their confidence. Knowing what to expect in a clinical setting and how a typical session will run made them feel more comfortable | ‘It oriented me to working with clients in an acute setting and has given me the confidence to do it in a real-world setting.’ (Participant 5). ‘Just getting that exposure to what’s expected of you. It helps build my confidence when I know a situation well from practice or experience.’ (Participant 3). |

| Skill development, n = 7 | The simulation afforded the ability to interact with a patient, which provided the opportunity for communication, problem solving, information gathering, and soft skill development. | ‘It increased my confidence in being able to enter a room and start up a conversation with a patient.’ (Participant 22). ‘Interacting with a patient and being able to come up with strategies on the spot.’ (Participant 28). ‘I was more aware of … how to behave in that circumstance.’ (Participant 14). |

| Authentic learning environment, n = 18 | To be able to apply theory and have hands-on practice of a dietetic consultation helped students to contextualize their knowledge and increased their confidence | ‘Physically completing something is completely different to on paper.’ (Participant 24). ‘[It] increased my confidence as I was able to put into practice what I learnt.’ (Participant 30). |

| Self-awareness, n = 7 | Students became aware of their knowledge or lack of and areas they can improve on before placement. | ‘[It] made me aware of what I know and what I can do better.’ (Participant 25). ‘I realized I knew more/more confident in my knowledge than I thought.’ (Participant 4). |

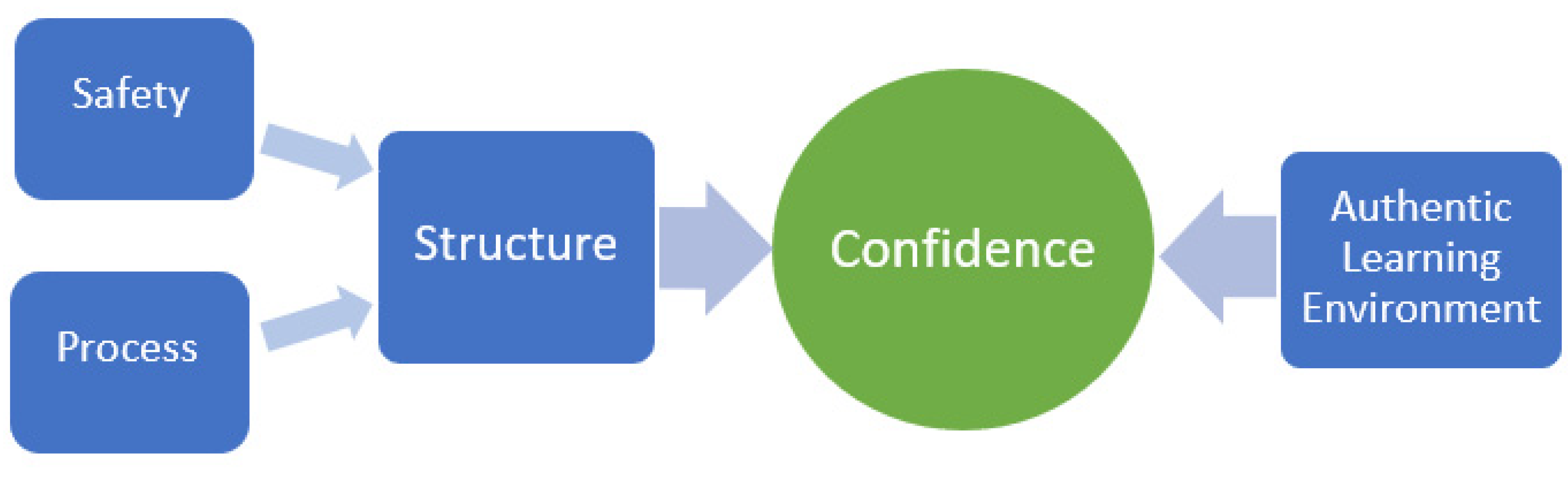

| Simulation process, n = 4 | The way in which the simulation was structured and implemented was important to support learning. Students appreciated that they were not assessed and could observe and learn from each other. | ‘[It was a] safe space to practice practical skills and see others doing the same. Good opportunity to discuss improvements or extra information in debrief session.’ (Participant 11). ‘Allowed you to make mistakes in a safe environment.’ (Participant 21). |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wright, H.H.; Cameron, J.; Wiesmayr-Freeman, T.; Swanepoel, L. Perceived Benefits of a Standardized Patient Simulation in Pre-Placement Dietetic Students. Educ. Sci. 2020, 10, 186. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci10070186

Wright HH, Cameron J, Wiesmayr-Freeman T, Swanepoel L. Perceived Benefits of a Standardized Patient Simulation in Pre-Placement Dietetic Students. Education Sciences. 2020; 10(7):186. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci10070186

Chicago/Turabian StyleWright, Hattie H., Judi Cameron, Tania Wiesmayr-Freeman, and Libby Swanepoel. 2020. "Perceived Benefits of a Standardized Patient Simulation in Pre-Placement Dietetic Students" Education Sciences 10, no. 7: 186. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci10070186

APA StyleWright, H. H., Cameron, J., Wiesmayr-Freeman, T., & Swanepoel, L. (2020). Perceived Benefits of a Standardized Patient Simulation in Pre-Placement Dietetic Students. Education Sciences, 10(7), 186. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci10070186