Abstract

Research on behavior regulation was carried out after several months of social isolation, provoked by the pandemic, between the months of February and March 2020. In spring 2020, many higher education institutions began to introduce digital tools of education, remote learning, and distance teaching. The reaction during the first weeks and months was negative, but the experience of this remote regime of work and learning continued into the autumn semester due to COVID-19. This experience included the perceptions of new organizational approaches that were needed to regulate digital behavior as a specific type of strategy and choices made in the virtual space. This need was expressed in an understanding of the improvements to be implemented in the organization of educational processes at traditional institutions to efficiently apply the remote learning regime. Between December 2020 and March 2021, six focus groups were conducted to investigate if the regulation of behavior for remote work and learning (work for university administrative staff and academic teachers; studying for students) differed, with informal interviews also conducted to check the validity of the opinions formulated. The hypotheses of the lack of responsibility, and of iterative accomplishment of shorter and simpler tasks, were supported with the data obtained. The hypothesis on an imbalanced vision of mutual interests, and of the assessments of gains and costs of the remote activity, was confirmed. The hypothesis of the externalization of motivation was neither confirmed nor rejected, contradictory opinions were obtained, and, thus, further quantitative study is required. The conclusions based on the obtained results included support for improving the regulation mechanisms required to organize knowledge transfer when digital tools are applied at traditional educational institutions. To enhance the remote regime of learning, redesign and reorganization is necessary when considering the assistance needed by teachers and learners. Specific organizational efforts need to be implemented to restructure the teaching to shorter sequences, to stimulate the creativity of both teachers and learners (due to the readiness to experiment and the lack of critics, and constant access to online bases), and to identify the borders of the “sandbox” to clearly define and articulate the common rules of behavior.

1. Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic forced many educational organizations to transition to distance learning. This experience demonstrated the necessity of anticipating the effects of the remote learning process on individual choices and accounting for behavioral models.

The period at the beginning of the pandemic revealed the technical problems of transferring the educational process to the remote regime. By 1 April 2020, 1.598 billion students in the world were affected by the suspended activity of educational institutions, or 91.3% of total enrolled learners [1], and 1.2 billion of these students started the regime of remote learning [2]. The initial transition raised questions of equipment at home, access to the internet, and the minimal skills necessary for teachers and learners to use digital education tools.

The lack of technical elements required for education was a crucial factor for the dissatisfaction with remote learning and the first problem to be solved to finish the 2019-2020 academic year [3]. Internet connection covers large territories to different degrees, e.g., in Russia, some cities (even regional capitals in Siberia, such as Yakutsk) have weak access to telecommunications due to low population density, which is a problem that extends to many rural areas in countries with large territories such as USA, Canada, Australia, and the less privileged countries of Asia, America, and Africa. In Russia, the solution to this problem involved public efforts and private initiatives to collect and re-distribute devices to assure access to the global web for elderly people (at the beginning of social isolation) and for the students of high schools and universities; and, to a large extent, this problem was solved, at least, in megalopolises. By the beginning of schooling in September 2020, the essential technical solutions for remote learning were proposed at universities and schools in urban areas; the supply of equipment and improvement of Internet access infrastructure was accomplished, and the software for the educational process was selected based on the numerous proposals by the universities’ administrations.

The second stage of distance learning implementation related to the understanding of the new behavioral models that appeared within the remote educational process. Teachers and students noted the fostering of new norms of behavior that were accepted or faced, and the new habits and new concerns they were required to cope with [4,5]. These new issues concentrated on the socio-psychological factors that influenced the regulation of the choice of behavioral models by both sides involved in the learning process, namely, teachers and learners. The administration of educational institutions undertook a number of broad (but not deep) attempts to fix some superficial rules, but even these were not intended to regulate or govern the interaction norms or learning values’ scale [6,7].

The administrative procedures were based on the common assumption that remote learning with digital communication tools is to be perceived as an ordinary face-to-face learning process, with the single difference being seeing the “faces” through the screen of a computer or smart-phone instead of looking face-to-face in the same physical space.

This paper intends to discuss the deeper changes of behavior within the learning cyber-space and to examine the potential improvements for the organization of educational processes that are to be implemented in cases where traditional education is transferred toward remote learning (especially in the emergency cases such as pandemic).

1.1. Literature Review

The research is based on the approaches of sociology, social psychology, pedagogy, and management. The interdisciplinary nature of the study helps to identify the connection between the psychological components of the behavioral model choice, the sociological analysis of the regulative mechanisms and their impact on the choice of behavioral strategies, the pedagogical approach, which includes a new knowledge creation and learning process configuration, and the governance of the groups’ behavior to improve the organization of interaction within the digital space.

The new social intelligence skills that appeared with the mass introduction of remote learning [8,9,10] included the use of messengers and social media that were largely assimilated by students during the last decade [5,11,12]. The cognitive practices included the exchange of knowledge through digital tools [13,14,15], the rules governing communication within forums [16], and the norms regulating the transfer of knowledge [17,18,19] were studied before COVID-19 and at the beginning of the pandemic [3,5,20].

The regulation of behavior and of the choice of the model to implement (e.g., between the rule respect or opportunistic model) is still less investigated [21,22,23]. The socio-cultural regulation includes the set of formal and informal norms and social controlling; thus, the general regulative mechanisms describe the factors determining the process of an individual’s strategy to make choices in the interiorized system of rules (a set of eligible behavioral models). The internal personal regulation structures include motivation and risk preference, while the social intelligence include (among other competences) a person’s ability to anticipate sanctions in the interaction between individual and community, which are reflected in responsibility and in social perception of others. These regulation factors (motivation, responsibility, risk, and evaluation of consequences) form the traditional socio-cultural regulation system and determine the “offline” behavioral strategy of a person:

- Motivation is a complex system of personality traits (determined to a large extent by organic nature, for example, the individual diversity of developed brain zones, such as the ability to process visual, auditory, or kinesthetic data) and socially based values that are acquired through socialization as a desirable orientation in the social space;

- Responsibility is expressed in caution (ecology of behavior), when a person chooses the options of behavior with the criteria of minimizing irreversible impact on the social or physical environment;

- Social perception reflects the understanding of factors that determine the behavior of others; it is based on personal motivations and constraints, and on experiences of previous social interactions when others have explained their motives;

- Readiness to make risky decision includes the capability to accept the long-term and complex consequences of the choice made; the short sequences of forecasted results allow actors to decrease the intellectual effort to model the future and to predict the outcomes of the decision, and the saving strategy (minimizing deliberation costs) makes people choose the environment with shorter fixed results.

The specific behavioral norms in internet communication, and the factors of the choice that participants make to respect or violate the norms, are the subject of study within the sociology of virtual reality and computer games [24,25,26,27,28,29]: “The game space, the media field of the game, engenders certain ethical norms and ways of gaming behavior” [30]. The detailed analysis of gamification in education [31,32,33] (understood as game mechanics used in non-game setting “to improve user experience (UX) and user engagement” [34]) can be useful for the improvement of the outcome of the knowledge exchange and assimilation, but for the purposes of this study, the games are considered as a specific space where particular perception and behavior models are cultivated.

The ludification of culture [35] and gamification in a diverse working or educational activity context, and for various purposes, are the signs of the evolution of the world perception, which has impact on the behavior regulation, the regulatory values, and regulative mechanisms in post-modern society [36,37,38,39]. Financial or administrative restrictions and incentives are widely used to orient participants’ behavior and to shape the correct models (e.g., ban applied to improper use of capitalization or spelling and grammar errors in chats) [16,38,40,41]. The social limitations and pressure by interactive sanctions are examined in socio-cultural studies [13,23,42], in research on cultural codes [43,44], and in “homo virtualis” [45].

The studies point out the deep change of cognitive elements in the process of knowledge creation and transfer due to the mass introduction and assimilation of digital communication tools. The outcome of remote learning highly depends on the attitudes [46] that include cognitive, affective, and conative components [47,48], but usually the first two factors (rational and emotional) of judgment are taken into account and represent the core subject of research, and the last one is ignored—the behavior is understood as resulted from the previous pair ratio-emotion.

1.2. Questions and Hypotheses of the Research

This paper intends to reveal the behavioral changes related to remote work and distance learning that play a considerable role in improving the educational process. A theoretical background analysis was conducted to apply the conceptual approach of behavior regulation in organizing online activities, including remote learning. Empirical research was designed to detect the elements of regulative mechanisms that are different for offline and online behavior, and to identify the concerns of the transition of the educational process to a digital environment, taking into account acceleration processes (in a situation where older generations, parents, and teachers at school or at university learn from younger people, the students [49], the process is described by sociologists as a prefigurative cultural transmission [50]). This research aimed to identify, on the basis of taxonomic analysis, the main groups of problems, build the structure of problem areas, and formulate hypotheses about the relationship between categories.

The essential question of our research was concentrated on the fundamental dynamic of the decision-making process that is seen as making the choice between potential ways of behavior, or the selection of behavioral models. The socio-culturally and historically determined regulative mechanisms are evolving in the digital environment, and the new space of quasi-reality produces a new regulative system of behavior.

The proposed hypotheses that were to be observed on the basis of the opinions of and assessments from students, teachers and administrators were as follows:

Hypothesis 1 (H1).

In the virtual cyberspace of clear rules and determined results, the intrinsic motivation is less efficient than the extrinsic one because of its understandable character—the intrinsic motivation has deep and, often, irrational roots, the external rewards are easy to calculate and predict;

Hypothesis 2 (H2).

The deterministic universe reduces the sense of responsibility—the infinite diversity of consequences is limited, usually, to a quantified outcome of probability, and there is no more complex responsibility, but a very simple following of rules to obtain a preliminarily anticipated result;

Hypothesis 3 (H3).

The economic, administrative, social, and personal (cultural and psychological) gains and costs of the remote activity is perceived in a different way by the participants taking different positions within the process of remote learning. In particular, the predominance of gains and costs is understood differently: each category of people assesses the costs incurred by themselves higher than the expenses and losses that were concerned other groups;

Hypothesis 4 (H4).

The illusion of the predictability of the cyberspace and, at the same time, of its “unreality” (“half-reality” [26]) provokes the idea of the enlarged “second chance” as a wide possibility to debug (redo) the committed acts, e.g., students assess as “unfair” the prohibition to pass many times the same test or the implementation of penalty points. Iterative actions in “partly real” virtual space help to train skills to solve similar tasks and to acquire habits to cope with similar situations.

The discussions carried out during the six focus-groups included the statements and answers that supported the hypotheses H2, H3, and H4, but the collected materials did not allow researchers to verify H1, as it lacked sufficient results to prove or reject it.

The research conclusion witnesses the existence of the general influence of the digital communication space on the regulation of behavior. The results also permitted us to conclude on the necessity to better inform and coordinate the activities and the conditions among the categories of people involved and, in particular, to help students and teachers with acquiring new skills and facilitating the communication as well as to help administrative employees of universities with reporting and data collection on the technical and infrastructural inventory.

2. Materials and Methods

This research aimed to enhance the knowledge creation and transfer within online communication due to the analysis of the gaps of organization in remote learning that have considerable impact on the behavior of the participants receiving distance education. The regulators of the behavior historically include the values and motivation (orienting human behavior), the sense of the risks and responsibility for the effects and consequences of the decisions made (rules and sanctions as well as the long-term and collateral outcomes), the negotiation of the balance of perceived investments and expected gains (agreements on the interests), and the options to reconstruct the previous state of affairs and to restart from a zero point (“second chance”).

The null hypotheses of the research implied that the same levels and same components of motivation, responsibility, agreed balance of interests, and restarting are typical for both traditional education and remote learning.

According the purpose of the study and the hypotheses proposed, the null hypotheses of the research were as follows:

Hypothesis 5a (H5a).

The weight of intrinsic and extrinsic motivation is the same for remote learning as for traditional face-to-face learning, and the digital technologies and online space does not influence the interrelation of motivation types;

Hypothesis 5b (H5b).

The responsibility does not depend on the clarity of rules and does not change with the transfer of activities toward the remote regime;

Hypothesis 5c (H5c).

The organization of remote learning is well balanced, groups do not feel concerned that their interests are ignored, and their resources invested are not underestimated;

Hypothesis 5d (H5d).

The temporary axes is linear and directed in both physical and virtual reality: it is impossible to revert back to the previous stage of a process in the physical world or in cyberspace. There are some fields and activities, where the player can repair (restore the state of objects, improve relationship, etc.) and those where no one can delete the mistakes and erroneous decisions. The physical universe has the same volume of “repairable” phenomena as the virtual world.

To solve the set tasks, to check the hypotheses, and to systemize the factors of efficient remote activity organization, six focus groups were held: one among secondary school teachers (11 people, Ns = 11) and five among higher education participants.

At universities, two focus groups were conducted with students in undergraduate programs (nine students of the third year and five students in the fourth year of their bachelor’s degree, Nb = 14) and students in master’s degree programs (12 students in the first year of the master’s degree, Nm = 12).

Moreover, in higher education institutions, three focus groups were conducted with the participation of university staff: one among administrative staff, including heads of departments (13 people, Na = 13), and two among teachers (12 people offline, Nf = 12; and 11 people online, No = 11). The total number of respondents that took part in the research was 73 people (N = 73): 26 students (Nl = 26) and 23 university professors and associate professors (Np = 23).

The groups of students had a high level of homogeneity in terms of age: undergraduates had an average age of 20.6 years (sd = 0.852), while master’s students had an average age of 23.8 years (sd = 3.194). The focus group of teachers had the highest diversity by age (sd = 16.533), ranging from 27 to 82 years of age, with an average of 53.4 years; the university teachers that met online had an average age of 51.7 years (sd = 13.192), ranging in age from 27 to 72 years. The school teachers formed a heterogeneous group with a very similar level of standard deviation (13.080) and an average of 44.1 years. The administrative staff respondents had similar characteristics: 44.3 years on average (ranging from 23 to 64 years, with sd = 12.717); see Appendix A Table A1.

The focus group for secondary school teachers was attended by teachers from St. Petersburg and the Leningrad region.

The offline discussions were attended by students and employees of St. Petersburg universities, including: Peter the Great St. Petersburg Polytechnic University (“Polytech”); Herzen State Pedagogical University of Russia (“Herzen”); and St. Petersburg Electrotechnical University LETI (“LETI”).

The specialty of two of the universities is technical, but the students in the focus groups were studying in the technical, social-economic, and humanitarian faculties, with the common groups formed due to the specific seminars and conference sections that permitted the invitation of participants from different institutional faculties.

Online discussion allowed researchers to involve teaching staff from the enumerated universities of St. Petersburg and the professors from Italy (University of Cassino and Southern Lazio; La Sapienza University, Roma), from China (North-West A&F University, Yangling, Shaanxi) and Russia (Murmansk Arctic State University; Leningrad State University named after A.S. Pushkin). The authors recognize a potential significance of the socio-cultural context: the historical, political, and economic background influences behavioral models selection, especially, in the fields of responsibility, motivation, risk and ability to anticipate the balance of interests of involved actors—the four issues that were examined in the research. The research did not give the answer about the comparative weight of the socio-cultural context or of the transition of the learning process to the digital space, and such a study will require specific operational terminology and empirical indicators to identify and measure the impact of these groups of factors. Taking into account the eventual influence of socio-cultural regulation, however, the researchers decided to involve foreign colleagues in the discussion so their contribution could underlay further study.

The teaching and administrative staff was invited for the focus-group from the technical and social-economic faculties, with various backgrounds (e.g., doctors of physics, mathematics, and IT were teaching several courses in management programs, and vice versa, while those with a PhD in economics and statistics were working with technical students for mathematic modeling, etc.), for meetings both offline and online.

The format of the focus-groups allowed the researchers to build the discussions around four essential concerns that represent the traditional regulative mechanisms inherited from the history of society and now transferred from offline to online communication: values and motivation, responsibility for consequences, balance of relationships “me-others”, and irretrievable action and irreversible time flow to correct the consequences of the previously made decisions.

To discuss these hypotheses, the scenario (path of conversation) was built and the following issues were presented:

- The anonymity of the Internet was initially proposed to provoke the opinions and to stimulate people talking. The participants consider personal identification and the possibility of creating new profiles and accounts in social media and in games. How do these options influence behavior? In both real communication (personal profiles in social media and messengers) and game communication (avatars), the participants have the theoretical possibility to “kill” their personage, but in fact, the game players are fostering their avatars and appreciate the identity of their personage, the “hero”. Is this sense of responsibility the same both offline and online? The groups raised question on whether image and reputation have the same value in the physical and virtual world, or if the character of the avatar can be lost easier and the social media profile can be forgotten without deep consequences (H2);

- The possibility to correct mistakes has several degrees and options: in the physical reality time is linear and each correction is, in fact, a new action based on the previous background. In online activities, the time counter can be re-launched, the new experience and knowledge is assimilated by the person (not by personage), and usually the previous attempts’ results are completely “deleted” from memory and not “forgotten”, because in real life to “forgot” often means a convention between participants to avoid remembering and reminding. The notions of excuse and absolution are less implemented in the online world than offline because people rarely need to apologize as it is enough to respect rules and to apply sanctions (without an option of a pardon) against someone who violates those rules (H4);

- The motivation plays the role of enabling criteria to choose a behavioral model and take action; these criteria, set in online environment, are related to others’ opinions within social media (presented with likes and dislikes), in games, online work, and learning activities where a participant can award assessment points. Any action produces effects, the choice is made according the internal criterion of the process happening (intrinsic motivation) and the expected external effects that will allow the actor to obtain external rewards (extrinsic motivation). The groups argued if likes in social media and anticipated rewards in other activities are more important than the pleasure of doing or of the process of communicating. Does the ratio of intrinsic/extrinsic motivation differ in offline and online activities? (H1)

- The organization of traditional activities (both work and learning) is well balanced and administrated on the basis of centuries (and even millenniums) of negotiations. The academic tradition was cultivated at universities in Eurasia since A.D. 489 (Academy in Gondishapur, Iran), in the Mediterranean area since 859 (Al-Karaouine, Fez, Morocco), and in Western Europe since 1088 (Bologna, Italy); the work conditions and distribution of functions and duties among participants of enterprise were coordinated, over several centuries, within guilds and factories. Remote work and learning represent a new environment to re-negotiate, but all the involved parties have an illusion that they know enough about the interests, costs, and gains of the other sides. The talk was concentrated on the question: if some resources used and opportunities appeared are underestimated or over-estimated by others, which elements are not assessed in a correct way? For example, students and teachers often had no idea of the difficulties faced by the administration of educational institutions during to the pandemic, due to the quadruple subordination to the offices of education, healthcare, monitoring agencies, the human wellbeing service, and to the orders and instructions of the coronavirus emergency headquarters) (H3).

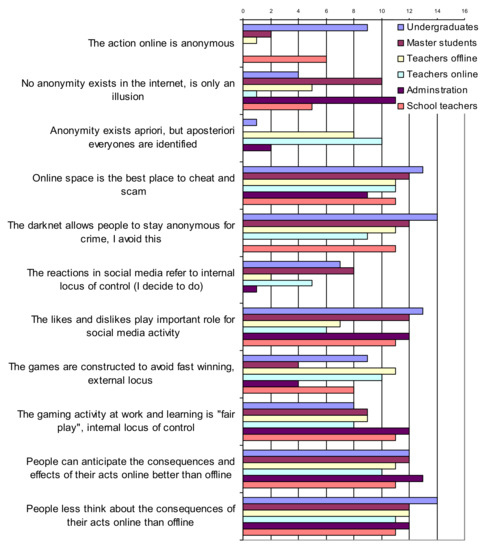

During the discussion, some of the ideas were supported by many participants, and some of them were scrutinized from different points of view. The results of registered frequency of mention are presented in diagrams (Figure 1, Figure 2 and Figure 3).

Figure 1.

The frequency at which anonymity and responsibility issues were mentioned during discussions.

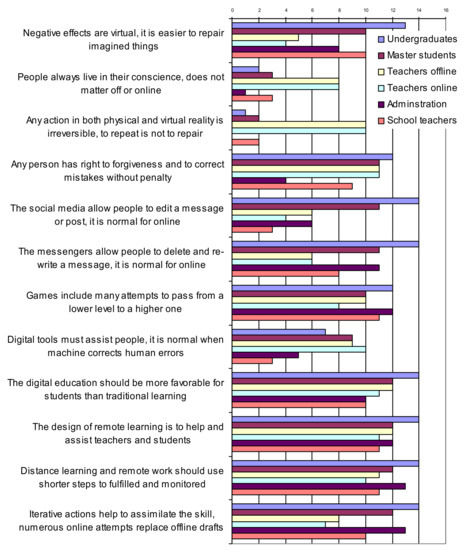

Figure 2.

The frequency at which the options of re-starting in offline and online activities were mentioned.

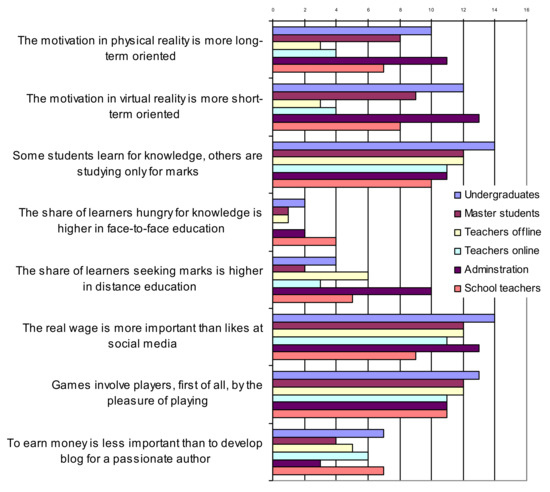

Figure 3.

The frequency at which some ideas on the motivation of offline and online behavior were mentioned.

3. Results

The results are presented according to the order of their appearance in the scenario of discussions and followed the unfolding logic of the focus-group.

3.1. Responsibility as a Regulative Mechanism for Offline and Online Activity

H2 (decrease of responsibility) was checked with the following groups of issues:

- Anonymity on the Internet;

- Psychological features of personality to balance internal and external locus of control;

- Unfairness of games mechanics—players can buy specific equipment and capacities for their avatars, and the algorithms are adjusted to simulate hazard by difficulty and to prevent easy success (“a good place to cheat because I deceive the system, the machine, not humans”, a student said);

- Equity and accuracy of game activities at education and work—if participants follow the rules, they are rewarded according to the initially announced scale.

These issues obtained the support of different groups, with Figure 1 representing the number of people that supported each statement (the total is higher than 100% of the number of people participating because the respondents usually expressed more than one opinion).

3.2. Risky Behavior Is Typical for an Online Environment Perceived as a Secure Sandbox

The hypothesis H4 supposed that restarting from zero was typical for online activity in a considerable number of situations, fields, and at higher scale than for offline. It was checked with the following groups of issues:

- All that happens on the Internet happens in a specific space that is not completely real—all that happens online should not be perceived as “really real”, as completely existing to the same degree as the events and actions in physical reality;

- A second chance should not be given to people, it does not matter if it is offline or online;

- Everyone can make a mistake, tests should account for diverse kinds of errors, misunderstanding of questions, and typos both offline and online at an equal or different degree;

- Games, applications, and bots suppose the immanent possibility to “start from zero” or from a previously saved location. If an avatar is killed, the person can launch again at the location, application, or conversation with a voice assistant. It is different from real life as if anyone died, they have no way to recover;

- Machines are created to help people, and it is logical that communication through machines and/or with machines is understood as “helped”. Digital interaction is supposed to supply a higher degree of correction in terms of erroneous actions and reducing human risks.

These issues provoked different opinions that were expressed by participants, and Figure 2 represents the number of people that supported each statement.

3.3. The Source of Motivation and Values as Criteria to Choose Behavioral Model Is under Question

The hypothesis H1 examined the dominance of extrinsic motivation as a typical feature of online activities. This hypothesis was checked with several blocks of questions:

- Motives act as criteria to choose the model of behavior, with short and long-term motivation, internal and external scales of values, and self-actualization as a complex motivating project;

- Scores in face-to-face learning in the classroom, primes and bonuses in the traditional workspace are the external motives. Do they dominate the pleasure of work or study?

- Everyday behavior is shaped with the reinforcement (behaviorists usually use a labyrinth with a white rat who has to find a piece of sugar in their research). This kind of social learning through the system of “approval-condemnation” is applied by humankind;

- The absence of likes can provoke the suicide attempt of a blogger;

- The motivation in physical reality is more balanced than in online activities, where the weight of extrinsic motivation is higher in the online environment and the intrinsic motives have more significance in offline traditional activities than within the remote regime.

These issues provoked a high diversity of opinions and examples from which we could not detect any clear common conclusion. Some of the positions are presented in Figure 3, but many of arguments were not included in this diagram because they represented the opposite visions of the behavior motivation in both the physical and virtual environment, and some of the positions were discussed by a minority of the participants (both opposite judgments were rejected or met with silence, such as the difference between the number of people that supported two sentences that are equal by meaning, but different with accents—the fourth and fifth lines—“intrinsic motivation is relatively more typical for physical reality” and “extrinsic motivation is relatively more typical for virtual reality”).

3.4. Overestimation of Self-Investment and Underestimation of Others’ Resources Use

Hypothesis H3 concerned the imbalance between perceived interests, gains, and losses of others. This idea was investigated with the following groups of issues:

- Economic issues: advantages (gains) and costs (individual or family resources implemented);

- Social concerns: negotiations and agreements versus conflicts; and communications and activities through the Internet (flash mobs, blogging, social media, etc.);

- Psychological outcome: satisfaction (typical for introverts) or stress and anxiety (for extraverted personalities);

- Family life: home as a place for rest or for activities, a decrease of attention with an increase in the volume of time passed together;

- Personal self-actualization: freedom or prison; pleasant and interesting pastime versus the hard task of structuring the “empty” time by themselves.

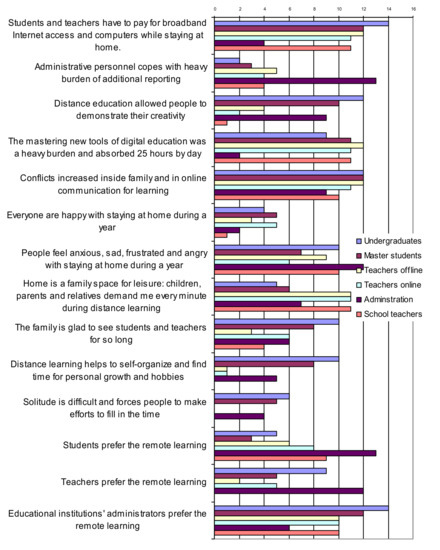

These groups of issues were discussed from the points of view of different groups, and Figure 4 represents the number of people who supported each statement.

Figure 4.

The frequency at which the assessment of reactions, gains, and losses of different groups involved in the remote learning were mentioned.

The differences demonstrated by groups of students, teachers, and administrative staff were a result of the specific perception of the world held each group. For our research, it was most interesting to consider the divergence of the assessments given to the same questions (e.g., are students happy about staying home for remote learning according to the opinions of students themselves, of teachers, and of administrative personnel).

The detailed data are presented in Appendix B (Table A2, Table A3, Table A4 and Table A5). The preliminary analysis allowed researchers to support the hypotheses H2, H3, and H4, but the study gave insufficient material for any valid conclusion about H1.

4. Discussion

The qualitative methodology used for this study limited the statistical significance and validity of the results obtained, but permitted us to find out the points of view, facets, and aspects that required special investigation for further research.

The quantitative methodology was implemented to treat the obtained qualitative data in this paper for two purposes: firstly, to help researchers to make a decision about the hypotheses, if they are worthy of further research or not; and secondly, to lay the foundation for a deeper analysis of the symptoms of the effects and phenomena that were examined. In this sense, the verification of the hypotheses was based on the analysis of the number of people who supported the proposed sentences, on the measuring of the standard deviation of responses (calculated on the basis of the shares of the choices of each sentence), and, in several cases, on the evaluation of the correlations between answers (to compare H2 and H4) as well as the negative correlations between choices (to compare several points of H2 and H3 in the field of involvement in games and lack of responsibility).

4.1. Evolution of Responsibility for Regulating Online Behavior

The general digital rupture between age groups is sometimes presented in the educational context as a difference between teachers and students, in favor of students as “digital natives”, who better master the virtual world than the generations of “digital migrants”. Nevertheless, both age categories at universities (younger students and elder teachers and administrators) gained their experience of digital behavior through social media, messengers, computer games, online banking, and shopping, etc., especially due to the common period of social isolation during pandemic in the spring 2020. The differences discussed demonstrated the deeper rupture related to the roles played in cyber-space by students who were looking for a better position in the future (achieving a higher waged job with the obtained knowledge and competency) and by academic staff, teachers, and managers who were providing the knowledge and controlling the outcome of learning. Controlling is an expensive process, especially in terms of transaction costs (“I spend more time to make sure that everyone has done their homework themselves than to prepare or renew my material for lectures”, a teacher said).

According to the content obtained, the variety of components of responsibility should be examined: the prognostics as the individual set of consequences of an act; the complex impact on the other people and social connections the person is interweaved in; the fairness as a personal principle of dignity; and the justice of hierarchical position in a scale of performances and, especially, the equity of scores according to the students’ merits.

The results obtained proved H2 (p < 0.05), wherein 98.6% of respondents supported the idea that people think less about the consequences of their actions online than offline (only one administrative employee, 38 years old, disputed this point, sd = 0.382) despite the better capacity to anticipate the effects of their acts online than offline (94.5% sd = 0.474). The actions and their effects seemed to be highly predictable online, with the separation of the place for illegal exchange, “darknet”, from the normal internet, which is, nevertheless, perceived as a good place for fraud as it is easier to cheat and scam (91.8%, sd = 1.451) (see Table A2).

These results demonstrate that H2 can be supported with several remarks of particular importance. The construction of games seems to be opposite to the construction of game activities at work and in remote learning: game design as an industry is based on the hazard of players and has two essential goals—to involve and to hold the player within the play process (unfairness of losing and winning is calculated, good and bad players should spend a determined time interval to achieve the next level). The game settings implemented for remote learning and at work are oriented to classify the more and less efficient participants (better and worse learners and workers) with the purpose of their assessment and improvement of their skills.

Another limit of responsibility was constructed with the “borders” of the virtual reality: if a failure occurs, it is included within the application or platform space, it cannot exit the field of a game and “go out” to the real world. If a failure occurs with a device (smart-phone, tablet, or computer), then the next step is to log out of the device and log into the user’ profile from another device. A failure is always limited to the virtual world of the concrete application or software (e.g., the failure in Minecraft does not concern the functioning of a profile on Facebook or TikTok: “I surf between channels and social media and leave my footprints everywhere”, a student remarked). This natural border between real and virtual worlds creates a habit of the limited responsibility that is dangerous if it is transferred directly to the real world where a person and their reputation is not divided into “sections” (e.g., an account on social media, presenting the private life of a person, is seen by colleagues, employers, and clients as a public profile). This illusion also provokes the under-estimation of the real human relationship based on digital communication: the posted remarks in social media (which are, usually, sincerer and more straightforward) or the conversations in a multiplayer game directly concerning the attitudes and positions of people as an entire solid personality.

The anonymity of the Internet was not perceived equally. The highest level of disagree was registered in the discussion of illusory anonymity (24.7% of respondents thought that online activity is anonymous, with sd = 3.444, and 49.3% believe that everyone is identified, sd = 3.659), with some of the respondents distinguishing between the anonymity at the initial point of the first steps and the full and complete identification of all of participants after an action (28.8%, sd = 4.740). This double opinion was more typical for university professors and it was supported by 10 of the 11 participants of the online focus group; it was not expressed by school teachers nor by master’s students, and it was supported by only 2 of the 13 administrative employees and by 1 of the 14 undergraduate participants.

4.2. Lack of Personal Commitment to Check Decisions before Pushing the Button

The question of H4 related to the acceptable iteration that mitigates the importance of each attempt and, consequently, reduces the commitment to each action.

It concerns, first of all, the perception of some acts as irreversible in real life, which can be easily recovered within an online space. The examples given by researchers (edit messages and posts in messengers and social media) revealed the ambiguity of their illusory simplicity: the cases mentioned were of the incorrect posts, which were deleted by the authors, but their screenshots were spread on the internet. The “law of oblivion” concerns the records in the global web about public persons that are to be deleted and no longer accessible. Nevertheless, everyone who had a profile in the social media vContacte was aware that they can ask the medium to open up their complete history with all deleted posts and dialogs (messages). Several respondents in each group made such requests and got their complete histories with thousands of pages where “nothing was missing” (“I have got a document with each my word, even deleted, even corrected immediately. Each my action is carefully archived by vContacte, I know this exactly and certainly now, because I saw it with my own eyes”, a lab manager argued). The same remark concerns games and the possibility to restore the “killed personage” or to undertake many attempts to achieve the next level: several people in each group mentioned the types of games constructed as the survival quest, where there is no option to recover the avatar, and the cases where the avatars were lost for different reasons (renewed computer or smart-phone, login and password lost, etc.).

Nevertheless, the considerable majority of respondents agreed about the idea that gaming produces habits in players where they have numerous attempts to achieve goals (86.3% in total, and 100% of secondary school teachers, but 72.7% of university teachers during the international focus groups that took place online), with a high degree of unanimity (sd = 1.123).

Close opinions were detected about the sense that the digital tools of education implemented for remote learning represented machines assisting humans. The idea was supported that remote learning was not just the replacement of learning from the classroom over to the Internet, on a pedagogical platform, to video and audio online communication tools, messengers, and social media as a ground for the same processes of knowledge transfer as in face-to-face regime. That means that remote learning requires specific pedagogical configuration and design to help teachers and students to create and exchange knowledge (98.6%, 72 from 73 respondents, only one head of an academic institution department disagreed with this idea; sd = 0.382). The process of learning needs the adaptation to the specific situation of online space, it is not enough to oblige the participants of the process to “come” from offline to the online environment.

Regarding the fundamental attitude toward humans as beings who have the right to err and to be forgiven (and it is a mercy from the side of forgiver), the opinions were quite unified around the Christian paradigm of absolution. A total of 79.5% of the respondents (majorities in each group, except administrative staff) agreed that the excuse is the basic way of community life, that no one is perfect, but people prefer to interact and to develop together (sd = 3.045). Only about a third of the participants (34.2%) supported the idea that all actions are irreversible (sd = 4.890), but among them, the clear distinction was related to the position with a high degree of unanimity in groups. The university teachers during the offline focus group (83.3%) and online discussion group (90.9%) supported the irreversibility of actions and consequences. Among them, the same respondents supported the right to forgiveness (91.7% of university teachers offline and 100% of those in the online discussion). This means that the two sentences were not contradictory to one another: time is linear and no one can come back to “repair” what was done, but the second chance should be given. Moreover, the understanding of both principles of social life (irreversible actions and a consequent specific action of apology and a last phase of mercy from the damaged side) seems to be a complex regulative mechanism that is realized in unconscious manner: from 0 to 2 persons in other groups supported the irreversibility of actions, but the vast majority in the same groups (students, managers, and school teachers) thought that online has specific opportunities to correct and, in particular, to delete and re-write a message over messenger (sd = 1.405 for these 4 groups, if we exclude the university teachers) and to edit a post or message on social media (sd = 1.123 for the 4 mentioned groups). They proposed that the online communication tools permitted a decrease in the irreversibility of actions, but they did not recognize this quality when talking about physical offline reality.

Finally, the iteration of repeating an action allowed a student to assimilate the agility to manage similar standard tasks as automated acts. This point provoked the feeling of threat, and whether, if in remote learning, the students can acquire the competency and ability to make decisions in non-standard situations. The fundamental illusion of a “programmed” reality leads to the impotency and incapacity to take action under unexpected circumstances and to solve unusual tasks. The tests, quantitative scores, and “mcdonaldization” of education [51,52] due to short MOOCs (massive open online courses) [53] should be completed with more sophisticated and diversified methods of teaching, tasks [54] and projects or autonomous works to be carried out by students. This specific feature is remarked in the gamedev (game development industry) as the concern of deadline, the infinite improvement of details of a virtual element, can lead to a failure of the whole launch of the final product because of delay. Unanimity, concerning the learning process, was expressed by participants, teachers, and students in relation to the sentence that digital education should be more favorable for students (94.5% of all respondents, with sd = 1.145).

A curious strong correlation (Pearson ratio 0.811) was revealed between the answers about anonymity a priori with total identification a posteriori, and support for the idea that people, in fact, in both the physical and virtual world are living within their conscience (a philosophic approach of subjective reality consists in recognition that a human has no instruments to prove that anything exists except her or his conscience). It is possible to suppose that the respondents who implemented the empiric approach (we know anything only if our senses give signals about a reality) also think that only our actions create important signals to be registered (only active agents are worthy of identification). The sample was too small to prove this conjecture on the basis of the accumulated data and to conclude about this correlation, but this assumption may be worth assessing in further research.

To conclude, the hypothesis can be supported (p < 0.05) that iteration is typical for the online education process because of the specific environment and technology used and the mediation of the internet.

4.3. Controversal Findings on Instrinsic and Extrinsic Motivation

The hypothesis of a shift from intrinsic motivation typical of offline activity to extrinsic motivation more typical of online environment was not confirmed or rejected due to conflicting data. The collected opinions were highly controversial in and of themselves with respondents often unable to express a clear decision about the dominance of one or another type of motivation.

During the discussion, many other dichotomies of motives were introduced, e.g., the short- and long-term motivations obtained considerable support from students and administrative staff (the whole sample showed sd = 3.062, the deviation in the focus groups of students and administrators was sd = 1.454). The content and form, as two values motivating different people to act, was also mentioned, and the motivations for survival (wage) and for personal growth (meta-motives) were proposed as an alternative to the dichotomy of the intrinsic/extrinsic motivation.

A unanimous opinion was expressed about the necessity to take into account both intrinsic and extrinsic motives in enhancing and enriching the organization of the educational process: the sentence “some students learn for knowledge, others are studying only for marks” was supported by 95.9% of all respondents, with a low level of divergence (sd = 0.806). A similar result was obtained on another quite obvious idea that “games involve players, first of all, by the pleasure of the game” (also 95.9%), but this conclusion concerned again both physical and virtual reality. The intrinsic motivation (pleasure of doing) plays dramatic role in the launching of an activity (to install a game and to switch on), but the extrinsic motives play a determinant role in making decisions inside the game, the learning, or the work activity. In the physical world, the dominance of internal process (“flow” [55,56,57]) or external rewards also depends on multiple factors, on personality, the moment of the action, and the stage of the communication, etc.

Another banal (but, in fact, not expected) result was the unanimity of respondents about the dominance of a real wage over the significance of likes and dislikes in the environment of social media (97.3% with sd = 0.903, all the groups supported unanimously this idea, except two school teachers). Even this trivial issue raised new questions, however, such as the distinction between a declarative hierarchy of needs and the real motives’ system that determines the choice between different behavioral models in various contexts, with diverse factors and variables. Another remark concerned the monetary value of likes, and all the students who participated in the research mentioned the direct link between the number of followers and the influencer’s wage from social channels (“My high school classmate is a blogger on YouTube with several hundred thousand subscribers, and she makes thousands of dollars a month from YouTube ads alone, and she publishes reviews on her channel and also gets paid for integrating with some large companies”, a student reported during a discussion about the social trend of personality self-actualization through social media). The intrinsic motivation helps to get paid higher and produces the extrinsic motivation for the others persons looking at the “etalon” (“Today, millionaire bloggers are role models for children, the benchmarks and examples to be imitated”, a high school teacher noted).

An interesting issue was found with regard to the difference between the support of two equal ideas about the dominance of the hunger for knowledge over the marks as motive for offline learning, and dominance of the hunting for marks and scores over the search for knowledge as a stimulus for the online educational process. The first idea accumulated only 13.7% of advocates among the total sample, while the second unified proponents who represented 41.4% of the sample, which is exactly three times more. The researchers concluded that this divergence meant the separation of the process of digital education that could not be directly compared with the face-to-face organization of learning.

Apparently, the chosen methodology and the proposed scenario were not conforming to the purpose of answering the question of the hypothesis H1: the motivation with the process and with the expected results (internal and external) is a complex phenomenon that requires further research.

4.4. Incorrect Assessment of the Others’ Balance of Interests

The social efficiency is based on the competence to evaluate and to consider the interests and limits of the partners (contractors, mates, and colleagues). The lack of capacity to perceive, measure, understand, and satisfy the need of the counterparty will provoke difficulties, that is why it is important to determine the correct balance of conditions of all participants in a process. For the educational process, the interests and circumstances are clearly defined by laws on education and the status of educational institutions (to give knowledge, to avoid fraud, etc.). However, real social activities usually involve the ability to circumvent the rules to some extent. Opportunistic behavior depends on the costs of following rules and on the potential gains and losses otherwise. The threat of opportunism, of choosing to bypass the rules or conventions, forces people to ask questions or explore the real interests and constraints that guide the choices and decisions made by social interaction partners.

This issue determines the whole efficiency of the social institutional process of knowledge transfer through the traditional graduating system. The universities offer the educational programs of bachelor’s and master’s degrees as the whole socialization process, while the digital space violates the basic elements of the traditional socialization with physical assistance and direct (usually, unconscious) perception of the others’ reactions. The complex process of imitation and adjustment to the reactions is disturbed in cyber-space due to the mediator, the screen, and all the infrastructure of Internet access. The various technical equipment, abilities, and experiences lead to the additional misunderstanding between the educational process participants.

The hypothesis H3 concerning the lack of understanding of mutual interests and vision of the remote work and learning organization was confirmed, and the most evident proof was the standard deviation of the answers of different groups (sd = 3.837 for the whole of the sample).

The positions of the groups were determining the importance given to the expenses of each type of actors: learners (undergraduates and master’s students), teachers (university professors and school pedagogical staff), and administrators. Comparison of the answers supported group by group provides a higher level of misunderstanding in the assessment of preferences in favor of remote learning:

- Assessment of the degree of students’ preferences for online education (sd = 4.242); the average assessment of agreement given by students was 3.693 pts (0 = no, 1 = indifferent, 2 = support), by teachers was 12.443, and by administrators was 21.292;

- For the evaluation of the teachers willingness for remote work (sd = 4.363), the average assessment given by teachers was 2.519 pts, by students was 8.057, and by administrators was 19.654;

- Respondents’ ideas on the administrations’ preference for the remote learning (sd = 3.448) included the average assessment given by administrators at 5.615 pts, by students at 18.250, by teachers at 18.818.

The levels of the standard deviation demonstrate the imbalanced vision of the weighed interests of the other groups. The level of the divergence was especially high between the opinions of participants of the pedagogical process (teacher-learner interaction, which has the constant and quite deep character of communication) compared with the administration staff evaluations. This could be explained by the direct dialogs during lectures, seminars, and the immediate exchange of impressions of the participants of the learning process, while university administrations usually build interrelations with students on the basis of bureaucratic procedures and impersonal communications.

The average assessment of costs and benefits of the remote learning regime that were given by each group demonstrates the deep rupture between groups for the majority of concerns (see Table 1).

Table 1.

The frequency at which the positive and negative outcomes of distance education and remote activities, as factors for imbalanced perception of others’ interests, were mentioned and shared by groups 1.

The small volume of samples determined the low level of statistical significance of the results, but they illustrate the divergence of assessments.

These results illustrate the weak mutual transparency of the organization of remote work and learning. From the point of view of professors and administrators, the distance education process requires important investments. For learners and teachers, the procedures are easily digitized and automated because of their formal character, and students and administrators improperly believe that the routine takes more time from teachers in the traditional educational regime than online.

The comprehension of this divergence allowed researchers to strongly recommend negotiations that were to be organized between the three essential groups of the education process: students, teachers, and managers. In particular, the negotiations should consider the resources needed (equipment, software, and communication infrastructure) [58,59,60], including the needs for professional purposes (such as computers) and the additional costs that are related to the re-organization of the order of life (to cook at home or to order delivery, to use the electricity and water at home, etc.), of the environment, and of space [61,62,63,64]. Professional assistance is required to solve tasks in the field of internal family relations at the moment of the crucial lack or resources and schedule limits (e.g., when the remote work and online learning happen at the same moment of time for the parents and their children).

5. Conclusions

The regulation of behavior was fostered over many centuries. The virtual world of literary oeuvres [28,65,66,67,68] and movies [68,69] permitted people to escape from physical reality and to jump into the wonderful imagined world over the course of several millennia (for books) or decades (for cinematography). The online world is, nevertheless, much more captivating and specific than books and films due to digital technologies and social communication development. The digitalization and gamification of the educational process was adopted to cope with the new remote regime introduced due to the pandemic. The digital regulation, and game as a specific form of activity, however, influence the re-organization of life at work and for learning [70,71]. The lack of responsibility and the position of “things” [72] or “puppets” [73] has a deep impact on the behavior of all participants in learning. According to M. McLuhan, “a game is a machine that can get into action only if the players consent to become puppets for a time” [73] (p. 263).

The re-positioning of all actors who take part in remote learning has an impact on the way they seek knowledge exchange and evaluate the quality of education [74,75,76,77]. The obtained results of this research helped to outline the regulative mechanisms relevant for the digital environment.

This research demonstrated the evolution of the regulative mechanisms that determine the behavioral models of both sides of the knowledge transfer process, teachers and students. The transition from the physical world of an educational institution toward the digital space implies several organizational changes to enhance the outcome of online learning. The re-configuration of pedagogical design and the re-structuring of the learning process organization is necessary. The articulation and simplification of tasks helps to assimilate better the standard competencies, but it does not stimulate creativity and so the universe of online information and the personal diversity of talented people is restricted to short exercises. These creative tasks are needed to construct a specific set of rules to improve the possibilities of experimentation within the sandbox of the educational space.

These preliminary conclusions should be developed, deepened, and widened through more generalized studies. Social and political actors have to investigate the new regulative patterns and to implement specific governance for the digital environment [78,79], remote work, and learning. These new issues can be useful for the improvement of the organization of online learning and for the enhancement of the intellectual outcome of education.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.N.P. and V.L.L.; methodology, N.N.P., F.D.; validation, M.Y.A., F.D.; investigation, N.N.P.; resources, V.L.L.; writing—original draft preparation, N.N.P.; writing—review and editing, N.N.P., M.Y.A. and V.L.L.; supervision, F.D.; project administration, N.N.P. and V.L.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This paper was financially supported by the Program for Strategic Academic Leadership and Peter the Great St. Petersburg Polytechnic University.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to restrictions of privacy.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

The demographic characteristics of the respondents of the study are presented in Table A1:

Table A1.

Characteristics of the research sample.

Table A1.

Characteristics of the research sample.

| Undergraduates | Master’s Students | Teachers Offline | Teachers Online | Adm. Staff | School Teachers | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average age, years | 20.6 | 23.8 | 53.4 | 51.7 | 44.3 | 44.1 |

| Standard deviation 1 | 0.852 | 3.194 | 16.533 | 13.192 | 12.717 | 13.080 |

| Female, % | 57.1 | 58.3 | 41.7 | 54.5 | 84.6 | 90.9 |

| Male, % | 42.9 | 41.7 | 58.3 | 45.5 | 15.4 | 9.1 |

1 Standard deviation is calculated by age.

Appendix B

The frequency at which the ideas discussed at focus-groups during the research study, presented in the Table A2, Table A3, Table A4 and Table A5, were mentioned.

Table A2.

The frequency at which anonymity and responsibility issues were mentioned during discussions.

Table A2.

The frequency at which anonymity and responsibility issues were mentioned during discussions.

| Issues | Statements to Provoke Discussion | Undergrad. | Master Stud. | Teachers Offline | Teachers Online | Adm. Staff | School Teachers | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anonymity | Action online is anonymous | 9 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 24.7% |

| No anonymity exists on the Internet, it is only an illusion | 4 | 10 | 5 | 1 | 11 | 5 | 49.3% | |

| Anonymity exists a priori, but a posteriori everyone is identified | 1 | 0 | 8 | 10 | 2 | 0 | 28.8% | |

| Cheating or crime | Online space is the best place to cheat and scam | 13 | 12 | 11 | 11 | 9 | 11 | 91.8% |

| The darknet allows people to stay anonymous in crime, I avoid this | 14 | 12 | 11 | 9 | 0 | 11 | 78.1% | |

| Locus of control | The reactions in social media refer to internal locus of control (I decide what I do) | 7 | 8 | 2 | 5 | 1 | 0 | 31.5% |

| The likes and dislikes play an important role in social media activity | 13 | 12 | 7 | 6 | 12 | 11 | 83.6% | |

| Games are constructed to avoid fast winning, external locus | 9 | 4 | 11 | 10 | 4 | 8 | 63.0% | |

| The gaming activity at work and learning is “fair play”, internal locus of control | 8 | 9 | 9 | 8 | 12 | 11 | 78.1% | |

| Online vs. offline | People can anticipate the consequences and effects of their acts online better than offline | 12 | 12 | 11 | 10 | 13 | 11 | 94.5% |

| People think less about the consequences of their acts online than offline | 14 | 12 | 12 | 11 | 12 | 11 | 98.6% |

Table A3.

The frequency at which the options of re-starting in offline and online activities was mentioned.

Table A3.

The frequency at which the options of re-starting in offline and online activities was mentioned.

| Issues | Statements to Provoke Discussion | Undergrad. | Master Stud. | Teachers Offline | Teachers Online | Adm. Staff | School Teachers | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unreal world | Negative effects are virtual, it is easier to repair imagined things | 13 | 10 | 5 | 4 | 8 | 10 | 68.5% |

| People always live in their conscience, does not matter if it is off or online | 2 | 3 | 8 | 8 | 1 | 3 | 34.2% | |

| Irreversible actions | Actions in both physical and virtual reality are irreversible | 1 | 2 | 10 | 10 | 0 | 2 | 34.2% |

| Any person has right to forgiveness and to correct mistakes without penalty | 12 | 11 | 11 | 11 | 4 | 9 | 79.5% | |

| Habits to edit and correct | Social media allows people to edit a message or post, it is normal for online | 14 | 11 | 6 | 4 | 6 | 3 | 60.3% |

| Messengers allow people to delete and re-write a message, it is normal for online | 14 | 11 | 6 | 6 | 11 | 8 | 76.7% | |

| Games include many attempts to pass from a lower level to a higher one | 12 | 10 | 10 | 8 | 12 | 11 | 86.3% | |

| Assistance in remote learning | Digital tools must assist people, it is normal when a machine corrects human errors | 7 | 9 | 9 | 10 | 5 | 3 | 58.9% |

| Digital education should be more favorable for students | 14 | 12 | 12 | 11 | 10 | 10 | 94.5% | |

| The design of remote learning is to help and assist teachers and students | 14 | 12 | 12 | 11 | 12 | 11 | 98.6% | |

| Short steps to acquire simple skills | Distance learning and remote work should use shorter steps to fulfill and monitor | 14 | 12 | 11 | 10 | 13 | 11 | 97.3% |

| Iterative actions help to assimilate the skill, numerous online attempts replace offline drafts | 14 | 12 | 8 | 7 | 13 | 10 | 87.7% |

Table A4.

The frequency at which some ideas on the motivation of off and online behavior were mentioned.

Table A4.

The frequency at which some ideas on the motivation of off and online behavior were mentioned.

| Issues | Statements to Provoke Discussion | Undergrad. | Master Stud. | Teachers Offline | Teachers Online | Adm. Staff | School Teachers | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Short and long-term reasoning | The motivation in physical reality is more long-term oriented | 10 | 8 | 3 | 4 | 11 | 7 | 58.9% |

| The motivation in virtual reality is more short-term oriented | 12 | 9 | 3 | 4 | 13 | 8 | 67.1% | |

| Marks versus knowledge | Some students learn for knowledge, others are studying only for marks | 14 | 12 | 12 | 11 | 11 | 10 | 95.9% |

| The share of learners hungry for knowledge is higher in face-to-face education | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 4 | 13.7% | |

| The share of learners seeking marks is higher in distance education | 4 | 2 | 6 | 3 | 10 | 5 | 41.1% | |

| Gains and process in offline and online | The real wage is more important than likes on social media | 14 | 12 | 12 | 11 | 13 | 9 | 97.3% |

| Games involve players, first of all, by the pleasure of playing | 13 | 12 | 12 | 11 | 11 | 11 | 95.9% | |

| To earn money is less important than to develop a thematic blog (for a passionate author) | 7 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 3 | 7 | 43.8% | |

| Short steps to acquire simple skills | Distance learning and remote work should use shorter steps to fulfill and monitor | 10 | 8 | 3 | 4 | 11 | 7 | 58.9% |

| Iterative actions help to assimilate the skill, numerous online attempts replace offline drafts | 12 | 9 | 3 | 4 | 13 | 8 | 67.1% |

Table A5.

The frequency at which the positive and negative outcomes of distance education and remote activities, as factors for imbalanced perception of others’ interests, were mentioned.

Table A5.

The frequency at which the positive and negative outcomes of distance education and remote activities, as factors for imbalanced perception of others’ interests, were mentioned.

| Issues | Statements to Provoke Discussion | Undergrad. | Master Stud. | Teachers Offline | Teachers Online | Adm. Staff | School Teachers | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Economic and institution issues | Students and teachers have high expenses related to wideband internet, computer, and staying home | 14 | 12 | 12 | 11 | 4 | 11 | 87.7% |

| Administrative personnel cope with the heavy burden of additional reporting | 2 | 3 | 5 | 4 | 13 | 4 | 42.5% | |

| Creativity versus increased charge | Distance education allowed people to demonstrate their creativity | 12 | 10 | 4 | 2 | 9 | 1 | 52.1% |

| The mastering of the new tools of digital education was a heavy burden and absorbed 25 h by day | 9 | 11 | 12 | 11 | 2 | 11 | 76.7% | |

| Home and family concerns | Conflicts increased inside family and in online communication for learning | 12 | 12 | 12 | 11 | 9 | 10 | 90.4% |

| Home is a family space for leisure: children, parents, and relatives demand me every minute during distance learning | 4 | 5 | 3 | 5 | 2 | 1 | 27.4% | |

| The family is glad to see their members (students and teachers) for so long | 10 | 7 | 9 | 6 | 12 | 10 | 74.0% | |

| Psychological issues | Distance learning helps to self-organize and find time for personal growth and hobbies | 5 | 6 | 11 | 11 | 7 | 11 | 69.9% |

| Solitude is difficult and forces people to make efforts to fill in the time | 10 | 8 | 3 | 6 | 6 | 4 | 50.7% | |

| Everyone is happy with staying at home during the year | 10 | 8 | 1 | 1 | 5 | 0 | 34.2% | |

| People feel anxious, sad, frustrated, and angry staying at home for so long | 6 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 20.5% | |

| Preferences | Students prefer remote learning | 5 | 3 | 6 | 8 | 13 | 9 | 60.3% |

| Teachers prefer remote learning | 9 | 5 | 2 | 5 | 12 | 0 | 45.2% | |

| Administrations of educational institutions prefer remote learning | 14 | 12 | 10 | 10 | 6 | 10 | 84.9% |

References

- UNESCO. COVID-19 Educational Disruption and Response. UNESCO Homepage. Available online: https://en.unesco.org/covid19/educationresponse (accessed on 11 May 2020).

- Li, C.; Lalani, F. The COVID-19 Pandemic Has Changed Education Forever. This Is How. Media, Entertainment and Information Industries, World Economic Forum. 29 April 2020. Available online: https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2020/04/coronavirus-education-global-covid19-online-digital-learning/ (accessed on 11 May 2020).

- Asanov, I.; Flores, F.; McKenzie, D.; Mensmann, M.; Schulte, M. Remote-learning, time-use, and mental health of Ecuadorian high-school students during the COVID-19 quarantine. World Dev. 2021, 138, 105225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almazova, N.; Krylova, E.; Rubtsova, A.; Odinokaya, M. Challenges and Opportunities for Russian Higher Education amid COVID-19: Teachers’ Perspective. Educ. Sci. 2020, 10, 368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ababkova, M.Y.; Cappelli, L.; D’Ascenzo, F.; Leontyeva, V.L.; Pokrovskaia, N.N. Digital Communication Tools and Knowledge Creation Processes for Enriched Intellectual Outcome—Experience of Short-Term E-Learning Courses during Pandemic. Future Internet 2021, 13, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aladyshkin, I.V.; Kulik, S.V.; Odinokaya, M.A.; Safonova, A.S.; Kalmykova, S.V. Development of Electronic Information and Educational Environment of the University 4.0 and Prospects of Integration of Engineering Education and Humanities. In Integrating Engineering Education and Humanities for Global Intercultural Perspectives; IEEHGIP 2020; Lecture Notes in Networks and Systems; Anikina, Z., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; Volume 131, pp. 659–671. [Google Scholar]

- Ipatov, O.; Barinova, D.; Odinokaya, M.; Rubtsova, A.; Pyatnitsky, A. The Impact of Digital Transformation Process of the Russian University. In Proceedings of the 31st DAAAM International Symposium, Mostar, Bosnia and Herzegovina, 21–24 October 2020; DAAAM International: Vienna, Austria, 2020; pp. 271–275. [Google Scholar]

- Fedorov, D.A.; Ababkova, M.Y.; Pokrovskaia, N.N. Educational Services for Intellectual Capital Growth or Transmission of Culture for Transfer of Knowledge—Consumer Satisfaction at St. Petersburg Universities. Educ. Sci. 2019, 9, 183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baranova, T.; Kobicheva, A.; Tokareva, E. The Impact of an Online Intercultural Project on Students’ Cultural Intelligence Development. Lect. Notes Netw. Syst. 2021, 184, 219–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trostinskaya, I.R.; Ababkova, M.Y.; Pokrovskaia, N.N. Neuro-technologies for knowledge transfer and experience communication. In Proceedings of the European Proceedings of Social & Behavioural Sciences (EpSBS), Chelyabinsk, Russia, 1–3 November 2018; Volume 35, pp. 10–18. [Google Scholar]

- Henry, D.S.; Wessinger, W.D.; Meena, N.K.; Payakachat, N.; Gardner, J.M.; Rhee, S.W. Using a Facebook group to facilitate faculty-student interactions during preclinical medical education: A retrospective survey analysis. BMC Med. Educ. 2020, 20, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toker, S.; Baturay, M.H. What foresees college students’ tendency to use facebook for diverse educational purposes? Int. J. Educ. Technol. High. Educ. 2019, 16, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almazova, N.; Bylieva, D.; Lobatyuk, V.; Rubtsova, A. Human behavior as a source of data in the context of education system. In SPBPU IDE’19: Proceedings of Peter the Great St. Petersburg Polytechnic University International Scientific Conference on Innovations in Digital Economy; ACM: St. Petersburg, Russia, 2019; p. 37. [Google Scholar]

- Brusakova, I.A. About problems of management of knowledge of the digital enterprise in fuzzy topological space. In Proceedings of the 2017 20th IEEE International Conference on Soft Computing and Measurements (St-Petersburg), St. Petersburg, Russia, 24–26 May 2017; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 792–795. [Google Scholar]

- Pokrovskaia, N.N. Global models of regulatory mechanisms and tax incentives in the R&D sphere for the production and transfer of knowledge. In Proceedings of the International Conference “GSOM Emerging Markets Conference 2016”, St. Petersburg, Russia, 6–8 October 2016; St. Petersburg University Graduate School of Management, GSOM: St. Petersburg, Russia, 2016; pp. 313–315. [Google Scholar]

- Bylieva, D.; Lobatyuk, V.; Safonova, A. Online forums: Communication model, categories of online communication regulation and norms of behavior. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Rev. 2019, 7, 332–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamelink, C.J. Normative bases for communication. In Theories and Models of Communication; Cobley, P., Schulz, P.J., Eds.; De Gruyter: Berlin, Germany; Boston, MA, USA, 2013; pp. 59–83. [Google Scholar]

- Mureyko, L.V.; Shipunova, O.D.; Pasholikov, M.A.; Romanenko, I.B.; Romanenko, Y.M. The correlation of neurophysiologic and social mechanisms of the subconscious manipulation in media technology. Int. J. Civ. Eng. Technol. 2018, 9, 2020–2028. [Google Scholar]

- Beschasnaya, A.A.; Boiko, V.S.; Pokrovskaia, N.N. Spirituality in the cognitive process and the regulation of digital behaviour: Human ethics and machine learning. Acad. J. Sociol. 2019, 25, 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bylieva, D.; Zamorev, A.; Lobatyuk, V.; Anosova, N. Ways of Enriching MOOCs for Higher Education: A Philosophy Course. In Knowledge in the Information Society; PCSF 2020, CSIS 2020; Lecture Notes in Networks and Systems; Bylieva, D., Nordmann, A., Shipunova, O., Volkova, V., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; Volume 184, pp. 338–351. [Google Scholar]

- Barbillon, P.; Donnet, S.; Lazega, E.; Bar-Hen, A. Stochastic blockmodels for multiplex networks: An application to a multilevel network of researchers. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. A (Stat. Soc.) 2017, 180, 295–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khansuvarova, T.; Khansuvarov, R.; Pokrovskaia, N. Network decentralized regulation with the fog-edge computing and blockchain for business development. In Proceedings of the 14th European Conference on Management, Leadership and Governance, ECMLG 2018, Utrecht, The Netherlands, 18–19 October 2018; de Waal, B.M.E., Ravesteijn, P., Eds.; Academic Conferences and Publishing International Limited: Utrecht, The Netherlands, 2018; pp. 205–212. [Google Scholar]

- Shipunova, O.D.; Berezovskaya, I.P.; Mureyko, L.M.; Evseeva, L.I.; Evseev, V.V. Personal intellectual potential in the e-culture conditions. Espacios 2018, 39, 15. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, F.; Pokrovskaia, N.N.; d’Ascenzo, F. Information 4.0 for Augmented and Virtual Realities—Balance of Ignorance and Intelligence. Eur. Proc. Soc. Behav. Sci. EpSBS 2018, LI, 1821–1831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pimentel, K.; Teixeira, K. Virtual Reality: Through the New Looking Glass; Intel, Windcrest, and McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Juul, J. Half-Real: Video Games between Real Rules and Fictional Worlds; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Juul, J. The Art of Failure: An Essay on the Pain of Playing Video Games; Playful Thinking Series; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, M.-L. Immersion vs. Interactivity: Virtual Reality and Literary Theory. SubStance 1999, 28, 110–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogost, I. How to Talk about Videogames; University of Minnesota Press: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Buglak, S.S.; Latypova, A.R.; Lenkevich, A.S.; Ocheretyanyi, K.A.; Skomorokh, M.M. The image of the other in computer games. Vestn. SPbSU Philos. Confl. Stud. 2017, 33, 242253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, F.G.M. Practical Methodology for the Design of Educational Serious Games. Information 2020, 11, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danka, I. Motivation by gamification: Adapting motivational tools of massively multiplayer online role-playing games (MMORPGs) for peer-to-peer assessment in connectivist massive open online courses (cMOOCs). Int. Rev. Educ. 2020, 66, 75–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asanov, I.A.; Pokrovskaia, N.N. Digital regulatory tools for entrepreneurial and creative behavior in the knowledge economy. In Proceedings of the International Conference Quality Management, Transport and Information Security, Information Technologies (IT&QM&IS 2017), St. Petersburg, Russia, 23–30 September 2017; Shaposhnikov, S., Ed.; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 43–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]