1. Introduction

Today, large numbers of universities are available around the world and students are greatly concerned with the reputation and quality of the university regardless of its location and/or course expenses (e.g., world ranking, facilities available, world-class recognition). Obtaining governmental and/or industrial funding for the universities has also become competitive within the present turbulent financial environment and, usually, these financial allocations are carried out based on their performance. Additionally, universities have a huge responsibility to transfer knowledge to society for its economic development by conducting high-quality research and producing skilful graduates. Therefore, knowledgeable and skilful academic staff is a distinctive resource for any university to maintain the quality of teaching and conducting world-class research to elevate them in world rankings whilst taking a competitive advantage.

Despite the significance of the performance appraisal process (PAP) in the higher education sector to enhance the job satisfaction and productivity of their academic staff, only a limited amount of research work has been reported so far pertaining to this scope for both developed and developing countries [

1]. Additionally, most of the currently available performance measures in universities mainly focus on the research performance of their academic staff, and no or little attention has been focused on evaluating the teaching performance [

2]. Furthermore, it is still debatable as to whether PAP does more good or bad to the human resource management practices of an institution in terms of ‘soft’ indicators such as job satisfaction [

1,

3]. Additionally, education has been one of the major parts of the economy for some of the countries such as the UK, USA, India, and Indonesia and the number of universities across the globe are also increasing year by year. Under these circumstances, the PAP of universities is identified as a key area on which more research should be focused to widen the understanding while developing new theories/concepts.

This study aimed to explore the effects of the PAP on the job satisfaction of university academic staff. One of the largest universities in the United Kingdom (UK), referred to as the ‘source university’ in this paper, was selected to collect necessary data by questionnaires and interviews. The source university is one of the leading and most well-reputed universities in the UK and a member of the Russell Group, which represents the best 24 research-orientated universities in the UK. Presently, it is aiming to elevate its world ranking over the next few years. By aiming at this objective, the university has already launched several restructuring programmes by investing a significant amount of money, mainly for improving their infrastructure facilities, redesigning the degree programs, increasing the recruitment of students and academic staff nationally and internationally, etc. In such a massive organisational change, the pressure falling on the existing staff is inevitable. Hence, PAP as a human resource management process/tool has a huge mediating role to assess/understand the job satisfaction of the university academic staff (as an academic staff is one of the core human resources in any university) to receive the real benefits of this restructuring process.

This study focused on the higher educational institutions in the UK. Hence, it was assumed that the source university is a good example of representing the usual practices within the UK university environment, as well as of the well-known universities of the world. Therefore, the findings of this study should be applicable to any university in the world. Moreover, this study is expected to fill the existing gaps of the literature particularly relating to the performance appraisal of the academic staff, and then the future research should be extended to cover all the staff working in universities. Overall, practitioners, scholars, and consultants can use the outcomes and future recommendations of this study to extend their understanding and also for conducting further research and development.

2. Literature Review

2.1. History of Performance Appraisal

Performance appraisal is one of the major mechanisms of evaluating the performance of human beings. This has been carried out formally and informally throughout history. According to Eichel and Bender [

4], PA of employees traced back to the 3

rd century (A.D.), having been conducted to evaluate the performance of the members of official families (i.e., those who provided services for royal families) to reward them based on their performance. Ahamed [

5] revealed that during the time of building pyramids in ancient Egypt, performance appraisal was used as a method of motivating those workers. Likewise, several pieces of evidence can be found on the PA of employees in the early 19

th century. For example, the first industrially based PA was carried out by Robert Owen at his Cotton Mills in New Lanark, Scotland in the early 1800s to appraise the performance of his employees [

6]. Moreover, Army General Lewis Cass submitted a PA report to the War Department of the US Army in 1813 by rating the soldiers who were working under his command. General Lewis rated the performance of soldiers under three categories: being good-natured, a hard worker, and despised by all [

7]. Some pieces of evidence are available regarding the continuous evolution of PA activities throughout history. However, PA was not used to measure the administrative and professional performance of employees until 1955 [

8]. The revolution of PA started in the late 1980s with the beginning of employees’ payments based on their performance. However, this decision into performance-based appraisal was a rushed decision, as significant problems arose in the actual implementation and the evaluation process of the performance-related pay [

9].

With the increase of the interest/popularity in measuring the performance of employees since the 1970s, scholars were interested in identifying the key factors affecting the PAP [

10]. From a historic standpoint on the development of PA, in the 1970s it showed the performance on a scaled format to be popular, but by the 1980s this was changed mostly towards criteria/standards in PA to increase the accuracy in appraisal. Post-2000, it has mostly been focusing on specific contexts of PA and developments [

11]. Although it has evolved, a common theme with PA has been important as a tool to capture and to assess the dimensions of performance of employees as well as to ensure the measures in place will lead to a positive impact for organisations [

12]. Moreover, PA is identified as not only a tool simply to evaluate the employees, but to pinpoint potential avenues for employee development through training and other techniques [

13]. Therefore, in the present dynamic business environment, the PA mechanism is recognised as one of the pivotal human resource practices of many organisations worldwide [

13].

2.2. Theories Relating to the Performance Appraisal Process

In developing the understanding of PA, Boyd and Kyle [

14] indicated that the major criteria which should be used to assess the performance of employees include job-specific behaviour (e.g., volume of work, quality of work, knowledge about the job, dependability, innovation, etc.), core responsibilities of employees’ roles, and non-job-specific behaviour (e.g., punctuality, dedication, enthusiasm, cooperation, persistence, etc.). This is a key factor, as PA systems are expected to employ both quantifiable as well as non-quantifiable elements to gain a wider picture of the measures in place [

15]. Particularly, the assessment of such non-job-specific behaviour of employees will help an organisation to understand and improve employee job satisfaction levels [

16,

17]. Given this prominence, many organisations, in their appraisal process, tend to focus on non-job-specific behaviours such as cooperation and enthusiasm [

18]. For example, whilst the satisfied employees may finish their jobs on time with enthusiasm and dedication, allowing the organisation to achieve its goals and objectives more easily, the unsatisfied employees may evade their responsibilities and may be reported as having high absenteeism and less enthusiasm and dedication for their jobs. Likewise, the authors argued that the PAP is a result-oriented evaluation method that is used to assess the results obtained by employees in terms of organisational objectives. Fletcher [

19] delineated that the PAP has a strategic approach that integrates the activities of the employees with the business policies, targets, and objectives of an organisation. PAP as a process is, therefore, able to identify areas for performance improvement initiatives at the individual employee level and ultimately at the whole organisational level [

20]. Although a few different definitions can be found regarding PA, each of these provides the same idea that PA makes a bridge between employer and employee to understand the expectations of each other.

Numerous PA techniques have been presented over time and Oberg [

21] organised some of these methods into a logical sequence: essay-appraisal method graphic rating scale, field-review method, forced-choice rating method, critical incident appraisal method, management by objectives, work standard approach, and ranking method. In addition to these methods, Management by Objectives (MOB), cost-accounting method, balance-score method, psychological appraisal method, 360-appraisal method, the European quality framework model, the dashboard method, and 720-appraisal are also used as modern PA techniques [

22,

23,

24]. The major consideration of preparing this logical sequence can be recognised as the later proposed methods provide some improvements to avoid the weaknesses which were embedded in the previous methods.

Shrestha and Chalidabhongse [

25] identified two main factors which may affect the employees’ performance directly and/or indirectly: intrapersonal characteristics of employees (e.g., knowledge, skills, capabilities, job satisfaction, expectations, and attitudes) and the environmental factors of the workplace (e.g., quality of leadership, favourability of the workplace, the efficiency of the management system, politics, employer’s attitudes, and expectations). These factors may develop and/or hinder the employees’ performance. For example, while high intrapersonal and supportive/favourable environmental factors may assist employees to perform well, poor interpersonal and unfavourable environmental factors may hinder their performance and job satisfaction. Therefore, most organisations use the PAP as a key management mechanism to improve the employees’ performance by identifying the strengths and weaknesses of their intrapersonal characteristics. Additionally, PAP helps to decide on which weaknesses can be overcome and which strengths can be best utilised. Likewise, it is better to have a link between the PAP and other schemes such as rewards/punishments (i.e., financial and non-financial), salary increments, and promotions, etc. This may help an organisation to create an effective PAP which satisfies its employees. Furthermore, PAP is usually used to identify the environmental factors which may influence the employee’s performance. Therefore, PAP is considered as one of the most valuable instruments in the management toolbox as it greatly influences the employees’ work life and job satisfaction [

26]. In line with this, Kampkötter [

27] proved that the formal way of employee performance appraisal has a positive and high impact on employee job satisfaction. He further suggested that the job satisfaction levels get stronger in connection with a performance appraisal with financial consequences.

The importance of the PAP as explained by Carroll and Craig [

28] helps to see the position that the employee is currently in and what he/she needs to do to achieve organisational goals. Moreover, some of the previous authors [

29,

30] have explained some of the reasons why the PAP is important for a workplace and its employees:

PAP provides the required information to managers for making administrative decisions such as hiring, firing, promoting, replacing, transferring, terminating, rewarding, etc.

PAP provides feedback to employees to understand how well they performed and what they need to improve (e.g., job knowledge, skills, behaviour, attitudes, etc).

PAP helps managers in coaching and counselling their employees to improve on weaknesses and lack of skills.

Despite the above-mentioned advantages, some of the drawbacks which may tarnish the importance of the PAP have been identified by the previous authors [

31,

32,

33,

34,

35], and these are listed below:

Personal biases may occur, such as those based on race, sex, religion, etc. These may affect employees favourably or unfavourably.

Ratings provided by the different managers relating to the employees’ performance may not be comparable (e.g., work can be defined as quality work, creative work, integrity work and so on according to the perception of the appraiser).

Judgments on performance may be subjective, impressionistic, and arbitrary.

Delays of feedback and/or lack of feedback may create frustration when good performance is not quickly recognised and appreciated.

Silaban and Margaretha [

36] found that there is an effect of work-life balance on job satisfaction, employee retention, and so forth. Hence, they suggested that organisations should provide a good work environment and facilities to increase the motivation of the employees to ensure their work-life balance. Gopinath [

37] claimed that job satisfaction of employees would make a positive contribution to their job and also may lead to an increase in their effectiveness. Additionally, he highlighted that it is therefore important to have a good understanding of an individual’s total personality and value system to understand and also to describe his/her job satisfaction. Moreover, Kondrasuk [

38] presented a comprehensive review of the common problems in a typical PA process. It may cause the employees’ dissatisfaction and less productivity if these types of drawbacks are engaged in with a PAP. Furthermore, Levinson [

31] explained that PA should not be implemented as a technical process within an organisation, and it should be carried out as a human process without violating employees’ freedom. Moreover, a PAP may not support achieving ultimate organisational objectives and it may become merely an irrelevant and dishonest annual ritual of the organisation if the rating factors of employees have not been linked to the ultimate object of the organisation [

39]. In such a situation, the PAP becomes inefficient and may result in sealing the fate of the organisation by creating massive administrative problems [

35]. Therefore, it is obvious that a PAP should be closely linked with the organisational goals, objectives, strategies, and daily performance of employees to be a useful management process of a particular organisation [

40,

41]. Additionally, the absence of such a crucial management tool within an organisation may lead employees to less productivity, less motivation, and dissatisfaction while making them unclear about the organisational objectives [

25]. Therefore, the ultimate objective of a well-defined PAP should be the satisfaction of both employees’ and employers’ expectations.

2.3. Performance Appraisal in Higher Educational Institutions

According to the details discussed above, PA is an invaluable management tool even for the higher education sector to shape up the quality of teaching and research while creating a talented and satisfied academic staff within universities. Higher educational institutes are challenged by the requirement to constantly deliver the highest quality in academic work in their faculties and PA is used in ensuring the faculty performances always meet the required standards [

42]. In the university sector, performance appraisal is identified as a tool for measuring and developing the performance of staff members of a university on an individual or team basis in terms of their work process and achievements [

43]. Therefore, universities have drawn their special attention to developing performance appraisal systems related to both individual and organisational betterment and effectiveness. However, only a little-reported work has attempted to explore the importance of PA for the development of a university and the job satisfaction of its academic staff, as PA used in universities is mostly seen as a symbolic, box-ticking process [

3].

Some of the available works in the literature relating to performance appraisal in higher educational institutions are discussed in the following. Here, attention was focused on the UK education sector, as this research was aimed at evaluating one of the UK universities. Based on the literature, it is evident that few researchers have conducted studies exploring the application of performance appraisal methods and approaches in the UK higher education institutions in particular [

44].

In 1993, Haslam, Bryman, and Webb [

45] studied the development of a performance appraisal in UK universities. According to the study findings, university academics have an idea that there is a slight impact of performance appraisal in their academic careers concerning motivation and job performance. However, they admitted that the introduction of an appraisal system would help to change the then management culture of universities.

Mackay [

46] discussed the UK university administrative system under two major categories, namely the old and new systems. The administrative system which was followed by the UK universities before the 1970s was considered the old system. This was operated in a ‘highly trusted staff members’ environment that had not been closely assessing or monitoring the performance of the academic staff members. Therefore, it led universities to a favourable academic culture (i.e., academic freedom) with independent thoughts. Within the old university system, there was no formal appraisal process to evaluate the performance of their academic staff and they used an approach called the “laissez-faire approach” for managing the performance of the academic staff [

47]. Moreover, the academic staff worked within a ‘primus inter pares’ relationship on a collegial basis. Therefore, it is obvious that the old university system had a free academic culture which led their academic staff to innovations and inventions rather than focusing on short-term or low-risk research (i.e., research which may not lead to unsuccessful results) like today. According to Mackay [

46], a drastic change in the UK university administration occurred in the 1980s and she indicated this as the new administrative system. This is in line with this Türk [

48], who said that the formalised staff-appraisal system had been introduced to public universities in the UK in the 1980s. The main idea of introducing such a system was to meet the latest changes and requirements of the then economic situation of the UK. Under this new administrative system, the universities were expected to have market-oriented, customer-responsive, and economically acknowledging managerial culture rather than academic independence. As a result, the peaceful academic culture which had been embedded in the old system had disappeared from the universities while introducing a new culture that was highly focused on value for money instead of innovations and inventions. To adopt this managerial-based culture, personnel and management practices were also introduced into the university administration by the local authorities [

49]. Furthermore, competition and growing demands and requirements within the higher education sector and marketisation boosted the utilisation of performance appraisal methods in UK universities [

22].

According to Mackay [

46], embedding a managerial culture in the UK universities was justified by the government emphasising the need for greater consistency of the quality of both teaching and research throughout the UK university sector. Moreover, the limitation of the number of resources per student due to the rapid increase in the number of students in the UK universities was also a reason for creating a managerial culture within the universities. According to the Dearing Committee Report [

50], the available amount of resources per student was reduced by 40% from 1976 to 1995. Therefore, the universities had to compete with their competitors to attract enough funding from the government and industry due to these limitations of resources. As a result, the research assessment exercise (RAE) was introduced to rank the universities based on their performance. Ultimately, Human Resource Management (HRM) and PA practices were established within the university culture, despite academic freedom, to fulfil the requirements of the newly introduced RAE and employee legislation.

Under these circumstances, it seems that the academic staff of the UK universities have been working with less discretion within the new university culture. Then, the later researchers focused on investigating the most suitable performance appraisal approach (i.e., the best practice or the contingency approach) which would help the universities to achieve their goals while satisfying the academic staff [

47]. Usually, universities should have a flat administrative structure with a flexible and independent working environment that adheres to professional standards for creating knowledge and skills, leading to breakthrough research/innovations, etc. Therefore, Fletcher [

19] argued that the traditional PAP which is currently followed by the UK universities is an inappropriate method for evaluating the performance within the knowledge-based institutions. Consequently, several researchers have recommended using a contingency approach (i.e., there is no best way to manage employees and it should be tailored according to a particular organisation) for PA of the higher education sector rather than the formal best-practice method [

47]. The relevance of such an approach is even more relevant with tuition fees of students being doubled and students taking the role of customers; academics are faced with higher expectations and the idea of job uncertainty and performance expectations introduced to their work-life [

44].

3. Methodology

This research was mainly carried out by collecting information from the relevant sources via surveys and interviews. For this type of research, there are two commonly used survey methods (i.e., cross-sectional, and longitudinal) for the required data collection. Of these two methods, the longitudinal survey method is used to collect the data throughout a long period by sampling and scrutinising the source population repeatedly. The cross-sectional method is usually used to collect the information within a short period by delivering questionnaires, interviews, observations, etc. [

51]. This research was planned to accomplish its objectives within a short period and hence the cross-sectional survey method was selected to collect the data from the source population by delivering questionnaires and/or conducting semi-structured interviews, as the respondents could be met only once. A random group of the academic staff of the source university was taken as the targeted population for conducting surveys.

The source university has twenty different academic schools which are operated under three major faculties. Of these academic schools, five different schools within two faculties (i.e., the faculty of arts, humanities, and social sciences; and the faculty of engineering and physical sciences) were selected randomly for this study. The selected schools were:

School of biological sciences

School of electronics, electrical engineering, and computer science

Management school

School of mechanical and aerospace engineering

School of psychology

From here onwards, these five schools are referred to as biological sciences, electronics/electrical, management, mechanical/aerospace, and psychology respectively. However, no school from the faculty of medicine health and life sciences was selected to carry out the study as this faculty follows quite a different appraisal procedure from the other two faculties.

At the start of the required data collection, the documents which have been explained in the appraisal system of the source university were downloaded from its official website to investigate the relevant information about the PAP. Moreover, one of the non-academic staff members (i.e., a senior personnel officer) of the personnel department of the source university was interviewed to collect more information while clarifying some of the information provided on their website. Additionally, the available information in the literature on the PAP (i.e., the general information on the PAP and the information specific to the university PA procedures) was explored from the relevant academic journals, latest textbooks, and other related sources. Based on the information gathered from these sources, a questionnaire was prepared to distribute among the academic staff.

The questionnaire was first pretested with three academic staff members who are familiar with this field. Based on their inputs, several changes were made to the instructions, question order, and wording to improve the clarity and comprehensibility of the questionnaire. Second, the questionnaire was pilot tested with five known academics to have their thoughts/perspectives, and further minor modifications were made to finalise it based on the received comments/suggestions.

This questionnaire was mainly based on five sections:

General questions (i.e., school, position, age, etc.).

The understanding of the academic staff of the university PAP and their perception of it.

Satisfaction of the academic staff of the PAP and the behaviour of appraisers.

Staff members’ satisfaction of the correlation/s between the PAP and the schemes of rewards, promotions, training and developmental programmes, etc.

Staff members’ suggestions for possible improvements/changes to the current PAP.

The finalised version of the questionnaire is presented in the

Appendix A. Initially, 150 email addresses of academic staff were randomly selected through the university website (i.e., 30 for each selected school). Then the finalised questionnaire and a cover letter (that explained the purpose of the survey and confidentiality of the details that they provide) were delivered through an email. However, it was evidenced that this method was not appropriate for collecting information as only two responses were received back within the two-week timeframe. Therefore, it was decided to meet staff members in person to deliver questionnaires and to conduct semi-structured interviews. As a result, 35 responses (i.e., completed questionnaires) were collected within one month. However, one of the questionnaires collected with the response was discarded as this staff member provided responses only for a very few questions, and hence 34 questionnaires were considered for the study. When delivering questionnaires, we aimed to cover a fair cross-section of the whole academic staff (i.e., distributing questionnaires among the staff covering all possible ages, sex, positions, races, etc.) of the source university. In addition to the questionnaire, another randomly selected 25 staff members were interviewed in person (i.e., five members from each school) to explore their experience, understanding, perspective, and satisfaction regarding the PAP, and all of these responses from the interviews were used for the study. No financial incentives were offered for the interviewees and only a thank you card was given as a souvenir for successful participation at the end of the interviews.

The limitations of this study are recognised as follows. The first limitation may lie in the relatively small sample size and the limited number of academic staff. In particular, most of the women lecturers directly refused participation in either interviews or questionnaires. Additionally, it was felt that junior academic staff (for example, probationary lecturers, lecturers, senior lecturers) did not provide their genuine perception about PAP in the university. This calls for future research to include larger samples and address specific gender issues and junior-senior conflicts in the PAP in academia. The third limitation is that since only one university was considered, this does not indicate the holistic view of the PAP of the academic staff in higher education in the UK. Hence, comparative studies employing few UK universities should be recommended for further development of the field. The fourth limitation is associated with the use of cross-sectional data since the perception of academia about their PAP might change over time with experience and maturity. Hence, a longitudinal analysis would be more suitable to provide a more holistic view of the PAP of academic staff in higher education.

The qualitative data which was collected by questionnaires and interviews (i.e., altogether 59 respondents) were analysed under four sections to cover the initially specified research objectives. The information gathered is presented by numerical tables, percentages, graphs, etc. Moreover, the findings were analysed by dividing the source population into different categories (i.e., based on the schools, positions, etc.).

4. Results

4.1. The Overall Perspective of the Staff Members of the PAP

This section outlines the overall perception of the academic staff about the current PAP conducted by the university based on the answers provided by question Q-2.1. Accordingly, the perception of the academic staff is explained in

Table 1 under five rating scales (i.e., very bad, bad, not sure, good, very good) in terms of the pertaining schools. As shown in

Table 1, 32% of the academic staff indicated that the existing PAP of the source university is a bad process whilst 48% of them (Good—43% and Very good—5%) believe it is a good process. The rest, 20% of the academic staff, was not sure about the overall effectiveness of the existing PAP and most of them had pessimistic views on it. This is indicated by the answers provided by question Q-2.1. For example, some of them had answered that “this system has a lack of consideration of the quality of teaching”.

Overall, 52% (i.e., Bad—32% and Not sure—20%) of the source population seemed to be unhappy about the existing PAP. However, the percentage of satisfaction regarding the PAP of the academic staff differed in the various academic schools. The majority of the academic staff of the psychology school (Good - 67%; Very good - 0%) and, electronics/electrical (Good—50%, Very good—17%) were satisfied with the current PAP, while higher percentages of the academic staff of the biological sciences (Bad—45%, Not sure—33%), management (Bad—40%, Not sure—40%) and mechanical/aerospace (Bad—31%, Not sure—23%) seemed to be unhappy, as shown in

Table 1.

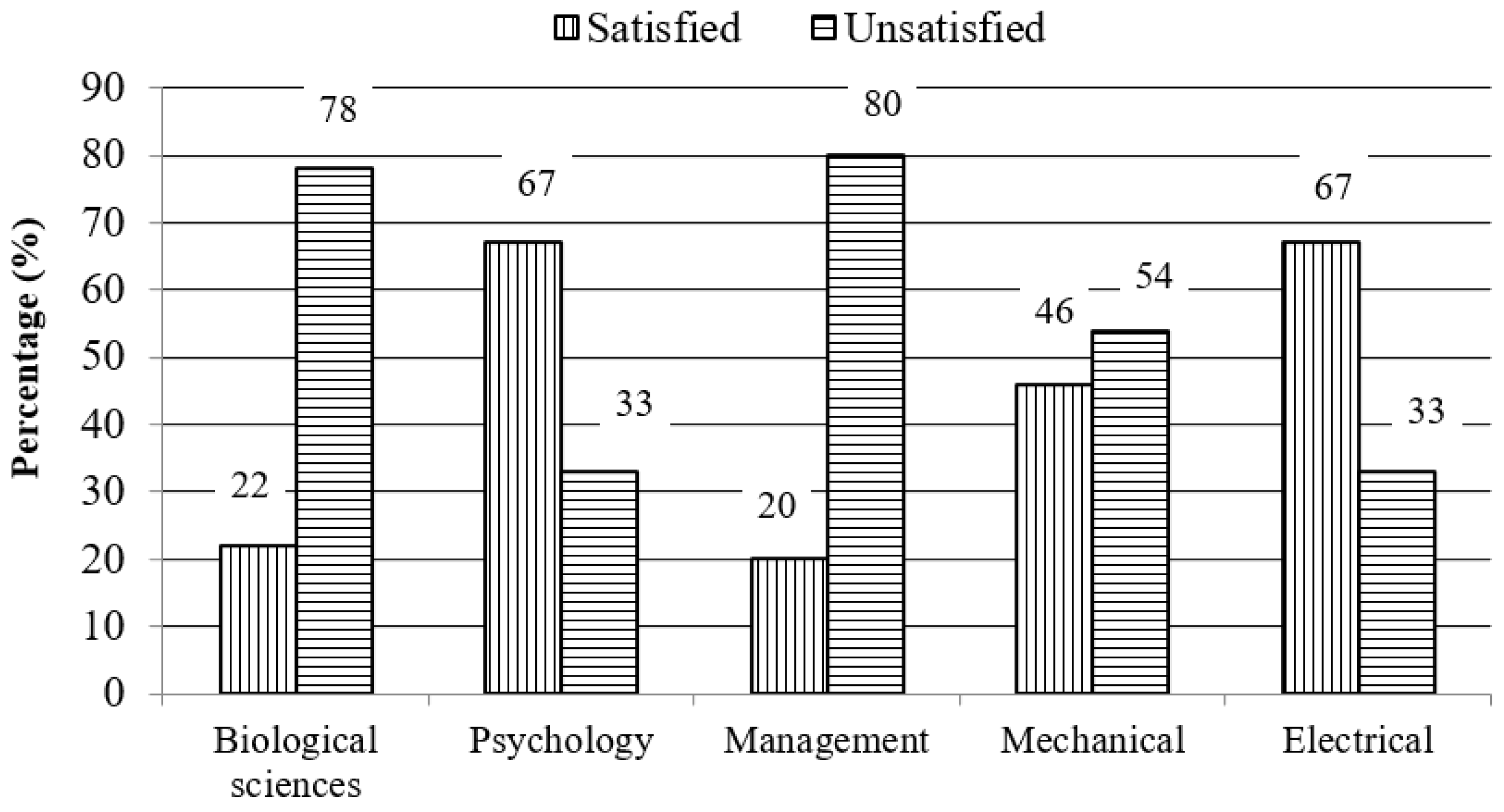

The rate of satisfaction of the academic staff of each school with the current PAP is shown in

Figure 1.

In the above, each staff member whose response in the questionnaire was stated as ‘Bad’ and ‘Not sure’ for Q-2.1 was considered as an ‘unsatisfied’ member, while those who indicated as ‘Good’ and ‘Very good’ were considered as ‘satisfied’ members. Further, the overall perception of the academic staff of the current PAP of the source university based on their job position was also analysed, and these details are furnished in

Table 2.

According to

Table 2, a higher percentage (Good—58%, Very good—12.5%) of the lecturers had optimistic views about the present PAP, while most of the professors (Good—18%, Very good—0%) revealed their pessimistic views. Although the facts and figures show that the staff members in the lower-level positions (i.e., lecturers, senior lecturers) are satisfied with the present system, the responses received by the questionnaires and interviews implied that they were rather reluctant to provide their real views on the PAP. Moreover, some of the lecturers rejected filling out the questionnaire and taking part in the interview. Some of the possible reasons for receiving such responses have been discussed in

Section 5.

The overall perception of the academic staff of the current PAP based on their origin (i.e., local and international) is described in

Table 3.

According to the details shown in

Table 3, all the foreign staff members showed their appreciation of the present PAP and a few of them even rated it as a very good process. From the data gathered, it was observed that some of the international staff members also were reluctant to portray their real views on the PAP. As shown in

Figure 1, a higher percentage of the academic staff in the electronics/electrical school was satisfied with the present PAP. However, this was because the majority of respondents of this school were foreign staff members. Perhaps, some international staff members may be very happy about the present PA mechanism in the source university compared with the mechanisms that they have experienced in their own countries or the countries that they worked for earlier. Otherwise, they would have felt that had they provided any negative views about the university administration, it could have an adverse impact on their careers.

4.2. The Level of Guidance Received from the Leaders to Understand the PAP

This section examines the level of guidance received from the leaders (i.e., line managers, directors of research, school managers, heads of the schools, etc.) for clarifying the details such as the goals and objectives of both the school and university, appraisal system of the school, and the performance criteria applicable to each position (i.e., part 3 of the questionnaire). The answers of the respondents are presented under four rating scales: Very helpful, Helpful, Moderate and Not helpful, and these details relating to each school are provided in

Table 4.

In general, most of the academic staff in each school mentioned that the guidance provided by their leaders to be aligned with the PAP of the university was either ‘Helpful’ or ‘Moderate’. Only a few staff members in the electronics/electrical showed their dissatisfaction with the guidance provided by their leaders and were rated as ‘Not helpful’, and all these respondents were professors. Moreover, some of the international staff members in the mechanical/aerospace and electronics/electrical showed their satisfaction by rating as ‘Very helpful’. Overall, it can be assumed that the academic staff members of the source university are satisfied with the level of guidance provided by their leaders to be adjusted with the PAP of the school/university, although many of them are unhappy about the current PAP of the university as a whole.

4.3. Examination of the Level of Guidance Provided by the PAP Itself to Reach the University Goals

The guidance provided by the PAP to reach the university goals (i.e., teaching and research) is explored in this section from the point of view of the academic staff. The view of the staff members on this particular aspect was examined by Q-3.9 of the questionnaire and the received responses are presented in

Table 5 based on five rating scales (i.e., Well supported, Supported, Moderate, Not supported, and Not sure).

According to the details given in

Table 5, a higher percentage of staff members within four academic schools believe that the guidance provided by the current PAP is good enough for achieving the goals of their schools and hence the university goals too. Therefore, the majority of them answered Q-3.9 as “Well supported/Supported/Moderate”. However, 55% of the electronics/electrical staff members had the idea that the present PAP is not supportive enough of achieving the university goals. Overall, 56% of the total population agreed that the existing PAP is good enough for reaching the university goals. However, this conflicts with the view of the staff members on the overall effectiveness of the existing PAP (i.e., the details shown in

Table 1) wherein 52% of the total population was unsatisfied about the overall effectiveness. Moreover, the majority of the interviewed staff members mentioned that the present PAP is greatly considered only with research achievements, and this has been further discussed in

Section 5.2. Therefore, the authors assumed that some of the reasons for this disagreement (i.e., between the views of the overall effectiveness and the support for achieving the university goals) were due to the biases and reluctance of some of the staff members in providing their real views.

4.4. Satisfaction of the Academic Staff of the Links between Salary Increments, Rewards, Promotions, and Training and Development with Their Performance

As mentioned in

Section 2.2, one of the major purposes of a PAP is to collect accurate information for making administrative decisions such as promotions, rewards, salary increments, and training and development, etc. [

29,

30]. On the other hand, if the above-mentioned administrative tasks have not been properly executed in an organisation, the importance and the requirement of a PAP will be diminished and hence it will be a process of wasting money and time. Therefore, in this study, it was expected to explore the links between these administrative tasks and the current PAP whilst identifying the level of satisfaction of the academic staff of these links. Part four of the questionnaire was designed to collect the required information on these factors and the information gathered is illustrated in

Table 6.

The information provided in this section is relevant to one of the most important and sensitive factors of an employee’s job satisfaction in any organisation. According to the details shown in

Table 6, 65% of the total population are unsatisfied (Very unhappy—7%, Unhappy—58%) regarding the relationships between the promotions, salary increments, rewards, and training and development with their performance but none of the foreign staff members was included in this group. The group of the academic staff (15% of the total population) who rated their view of the present PAP as ‘Very happy’ or ‘Happy’ includes foreign or newly recruited staff members only. Perhaps, the views of these fully satisfied staff members may not be fully genuine and can be due to their reluctance towards providing real views and/or due to the lack of experience in their academic position (i.e., particularly of the newly recruited staff members). The level of satisfaction of the staff members of each school of the links between these administrative tasks and their performance are illustrated in

Figure 2.

In this section, the respondents with the answers of ‘Very happy’ and/or ‘Happy’ were considered as ‘satisfied’ while those who are ‘Very unhappy’ and/or ‘Unhappy’ were considered as ‘unsatisfied’. Subsequently, the views of the academic staff on the links between the PAP and the above-mentioned administrative decisions (as a whole) were explored based on their job position/designation and the relevant details are described in

Table 7.

According to the details shown in

Table 7, the majority of the professors (Very unhappy—18%, Unhappy—64%) and readers (Very unhappy—0%, Unhappy—86%) are not satisfied regarding the links between the administrative decisions and PAP. However, 58.5% of the lecturers were either satisfied or highly satisfied with the links between the PAP and the administrative decisions.

5. Findings and Discussion

5.1. Overall View of the Academic Staff on the PAP

This study was aimed at exploring the satisfaction of the academic staff of the source university on the various aspects of the existing PAP. Fundamentally, it was realised that a higher percentage of the academic staff had a pessimistic view of the existing PAP of the source university, as was discussed in

Section 4.1. However, most of the staff members were happy about the level of guidance provided by their leaders (e.g., appraisers, head of the department, director of research) to align with the PAP. This means that the majority of the academic staff appreciates the behaviour/guidance of their leaders. Nevertheless, a discussion had with an appraiser revealed quite opposite details to the information gathered from appraisees. As explained by an appraiser, “

appraisees are not friendly and they do not believe appraisers during the appraisal process even though they are good friends within their day to day work life. Usually, appraisees see the appraiser as a spy who has been sent by the university administration to oversee the appraisee’s performance”. Therefore, he believes that this may cause damage to their friendship with appraisees in their day-to-day work lives. Furthermore, he explained that the current PAP has created a manager-subordinator relationship between appraiser and appraisee by following a managerial culture, although it was supposed to have a friendly environment similar to that of a leader-follower relationship within the school as described by Mackay [

46]. However, these details provided by the appraiser contradicted the overall perception of the appraisees (i.e., discussed in

Section 4.1) on the level of guidance provided by the leaders. Based on this information, it is clear that some of the academic staff members are rather reluctant (i.e., particularly those who are in junior-level positions) to provide their real view on the PAP. Although most of the academic staff indicated in their questionnaires that the present PAP is supportive in achieving the university goals, the majority of the interviewed staff members mentioned that the existing PAP had focused only on the research and very little attention has been paid to teaching aspects. One of the interviewed staff members mentioned that “

the source university is fully confused on achieving their goals”. Although there are some disagreements between the information gathered from the questionnaires and interviews on some of the issues, the perception of the majority of the academic staff about the links between the promotions, salary increments, rewards and developmental needs with their performance was the same (i.e., the majority were unhappy about these links). Some of the identified reasons which might be the cause for dissatisfaction of the academic staff of the present PAP of the university are discussed in the following sections.

5.2. Impact of the Politics within the University and Schools on the Performance of the Academic Staff

Based on the above analysis, it was clear that there were some biased responses especially from the foreign and junior staff members (i.e., lecturers, senior lecturers) whilst most of the professors expressed their views more openly. Based on the background information, it was felt that the major reason behind these types of bias responses might be the politics within the university/school. This was proven by the responses received from the senior staff, as they unhesitatingly provided their genuine feedback because they are already stable in their positions (i.e., they have reached their highest position in academia). Each school has their politics which affect the independence and performance of the academic staff as described by Shrestha and Chalidabhongse [

25]. As was realised from this study, the politics of the university negatively affected the different schools in various ways in all their activities including the PAP. For example, the university administration pressurises the heads of the schools if they have a bad deficit in their school budgets. The heads of schools in turn pressurise their staff members to inject more money into the school by attracting more internal/external grants, attracting more undergraduate/postgraduate students both local and foreign and making more collaborates/sponsors from industry, etc. Eventually, the performance of each staff member on such issues is evaluated via the PAP. The worst scenario may be the termination of service of the academic staff indicating their poor performance. As a result, the academic staff whose schools have higher budget deficits are under pressure during the appraisal process period as their poor performance may cause them to be dismissed from their services. “

In such a situation, the appraiser/line manager might be found as an enemy who dismisses if they are not friendly with the academic staff”. Therefore, these types of political effects may be one of the major reasons for creating dissatisfaction of the PAP for academic staff.

5.3. Impact of the REF (Research Excellence Framework) on the PAP

5.3.1. Consideration of the Quantity of Work Rather Than the Quality

As realised from the interviews, the REF assessment of the UK universities has directly affected the PAP of the source university. According to one of the senior lecturers of the management school, “The REF is a cornerstone of the current performance appraisal process”. The REF is an assessment that is usually carried out every six years to assess the quality and the quantity of the research conducted by UK universities. The results of the REF assessment are usually taken as the key indicator of allocating funds for the universities by the major funding bodies in the UK higher education sector. As a result of the REF assessment, universities are encouraging their academic staff to do short-term research and publications rather than long-term and/or risky projects which would deliver breakthrough results. Therefore, the university administration is reluctant to consider long-term or risky research with unequal performance (e.g., cancer research may take more than 10 years and sometimes it may end up without successful results). Likewise, universities count the quantity of the research output rather than the quality through the PAP. This was proven by the view of one of the professors in the school of biological sciences of the source university, as he explained that “REF has become geared to trying to measure and quantify the output of an assembly worker/salesperson rather than an academic”. Furthermore, he argued that most of the research outputs which are produced under such pressure would not be practically applicable and/or would not transfer the knowledge to economic/social development. Therefore, the current PAP which is based on the REF assessment is seen by the academic staff as a fruitless and time-wasting process that leads staff to produce low-quality outputs. A view of another senior professor of the school of biological sciences was that “it needs to row back from a reductionist stance where everything is reduced to a series of numbers and it doesn’t take into account matters in round e.g., research plans extending beyond 1–2 years and how it balances unequal performances in education and research failure (or lack of success for 2–3 years in research) would be fatal to career”. Under these circumstances, academic staff may have less possibility of considering long-term or highly challenging research, although they are willing to conduct such research. Such a narrow and stressful academic environment may never lead to creating world-famous scientists such as Albert Einstein, Aristotle, and Sir Isaac Newton in the future.

5.3.2. The Great Concern Only on Research

As pointed out by one of the heads of the schools, more than 90% of the university income comes from education (i.e., teaching) and hence maintaining the quality of education is one of the main objectives of any university. Of the three major PA criteria of the source university, education is one of the major criteria used to evaluate the performance of the academic staff. However, in practice, the evaluation of the teaching quality seems to be neglected in the current PAP of the source university. Usually, the director of research acts as the appraiser of each school’s PAP and he/she mainly focuses on the appraisee’s performance on research that has been carried out within the last academic year and the anticipated research plan for the next year. The appointment of the director of research as an appraiser for the PAP rather than the director of education emphasises the bias of the university PAP towards research. In such a situation, the staff members who may have less research performance due to their greater teaching load (i.e., due to spending time developing new causes, modules, etc) would be in a risky situation about their job. For example, each staff member should have at least one journal publication per year according to the REF and disciplinary action (e.g., lowering their position) may be taken against anyone who fails to meet this minimum requirement. Therefore, this imbalance between research and teaching may lower the quality of teaching and hence may lead to deteriorating the reputation of the university/school. Eventually, it may cause a reduction in the school income due to the lowered attraction of students.

5.4. Less Clearness of the Appraisal Form

Some of the staff members complained that the structure of the appraisal form is less meaningful as they believe that some of the details included in this form are useless. Therefore, most of the academic staff believe that the current PAP is a time-wasting activity. Consequently, they are only including cut-and-paste of details from their academic curriculum vitae to the PA forms without having much concern. Moreover, some of the respondents explained that completing the PA forms and conducting the PA interview seem like annual rituals which do not have any benefit for either the university or to themselves.

5.5. The Differences of Academic Specialisation between Appraisee and Appraiser

As pointed out by some of the staff members, the possible mismatches of the specialisation between the appraiser and appraisee should also be a negative fact for the effectiveness of the current PAP. This is because the appraisee may not receive a good appreciation as the appraiser may not understand the real value of the appraisee’s work.

5.6. Overall View of the Academic Staff Regarding the PAP of the Source University

The majority of the academic staff in all the schools indicated their dissatisfaction with the current PAP. Based on their feedback, the negatives of the present PAP apart from the above-discussed facts are:

Less transparency.

Objectives are vague and do not balance across individuals.

The volume of paperwork is high.

It is less likely to receive the developmental needs requested through the PAP.

It is sufficient to conduct the PAP once a year as it is a waste of time to conduct it twice a year.

On some occasions, the scope of the feedback received from the PAP is very narrow.

The same person remains as the appraiser for a long time.

Conversely, a few staff members mentioned that the feedback received via the PAP was good for them to identify the required personal improvements. However, only a very few positive responses supporting the current PAP were received throughout this study. Furthermore, it seems that the junior academic staff members are always at risk or uncertain of losing their jobs whilst senior academic staff members are fed up with their jobs due to the lack of freedom and/or less appreciation of their work. According to the view of the majority of the academic staff, getting promotions is extremely difficult within the university and if someone expects a promotion, he/she has to apply to another university. Overall, the impact of the source university’s performance appraisal process for job satisfaction of the academic staff is quite doubtable and it was felt that the academic staff members at all levels are not happy with the present environment of the university relating to the PAP.

6. Conclusions

The research was largely carried out by focusing on the major aim of the study and the primary and secondary data were collected as required. All of the data collected were analysed by aiming at the research objectives and, finally, all the initially set objectives were fully achieved. The key findings of this research are concluded in this section.

An investigation was carried out regarding the current PAP of the source university. The responses received by questionnaires and interviews revealed that all the academic staff members of the source university are aware of the PAP. However, the level of awareness was dependent upon individuals. Most of the academic staff had a pessimistic view of the effectiveness of the present PAP of the source university. Moreover, evaluation of the information provided by appraisees showed that most of them were happy with the level of guidance and behaviour of the appraiser. However, there were conflicts with the information provided by appraisers as they have realised that most of the appraisees were not happy with them. There was also a clear correlation between the bias of the information provided and the level of the academic positions. The majority of lecturers (i.e., junior staff) showed their satisfaction on most of the issues in the current PAP while the majority of professors (i.e., senior staff) were unsatisfied with these issues. It showed that the lower the level of the position, the higher the bias of the information that was provided. It was felt that this bias was majorly due to the politics attached to the school/university.

Most of the female staff members refused to answer the questionnaire or to take part in interviews, and the reason for this is unclear. Hence, future research should be invited to investigate the gender issues in PAP for identifying the real reason/s behind this reluctance of participation of female staff. Despite the academic school, the majority of staff members are dissatisfied with the links between the promotions, salary increments, rewards, and developmental needs with their performance. It seems that the present PAP of the source university is highly biased towards the research performance and very little attention is paid to teaching performance. The majority of the academic staff members are not happy with this. It was also felt that the existing managerial culture within the university hinders the performance of the academic staff, in general. Most staff members revealed that they are happy with an environment with academic freedom as they are self-motivated in their work. Most of the staff members are dissatisfied as the present PAP considers the quantity of research (i.e., due to the impact of the REF assessment) rather than the quality. Less clarity of the appraisal form, differences in the academic specialisation between appraisee and appraiser, the high load of paperwork, and conducting of the PAP by the same appraiser for a long period were also identified as some of the weaknesses of the present PAP of the source university. In conclusion, it was found that the performance appraisal of university academic staff is an area in which little investigation has been carried out by previous researchers. Therefore, further research in this area should be greatly invaluable for the staff and university development, as well as to provide high-quality teaching/research output for students.

7. Suggestions for Improvements

Some of the suggestions for improvements of the present PAP of the source university, based on the findings of this research, are presented in this section. Firstly, a clear link/s should be introduced between the PAP and promotions, rewards, salary increments, etc. The people who perform well should be recognised while providing monetary and non-monetary rewards. Not only the research but also the teaching performance should be evaluated through the PAP in an equal manner. It is better to appoint appraisers based on the majority’s consensus rather than appoint them only based on the satisfaction of the school authority. Moreover, appraisers should be changed periodically. The PA form should be updated based on the academic staff members’ suggestions and it is advisable to use an electronic process (e.g., provide a facility to fill the forms electronically with a well-organised evaluation algorithm) by reducing the volume of paperwork. It is better to conduct the PAP once a year within a well-organised, directed, and transparent environment. Reasonable and unbiased feedback should be provided through the PAP by cantering on the development of appraisees. In the future line of work, PAP should not be carried out fully based on the REF assessment (i.e., only focusing on short-term performance). Staff members should be permitted to carry out long-term research which may provide a breakthrough and more practical results. Hence, the PAP should be adjusted accordingly.